Primary Hepatic Mucosa-Associated B-Cell Lymphoma in a Patient with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis—A Case Ultimately Requiring Liver Transplantation

Abstract

1. Background

2. Case Presentation

2.1. History and Laboratory Findings

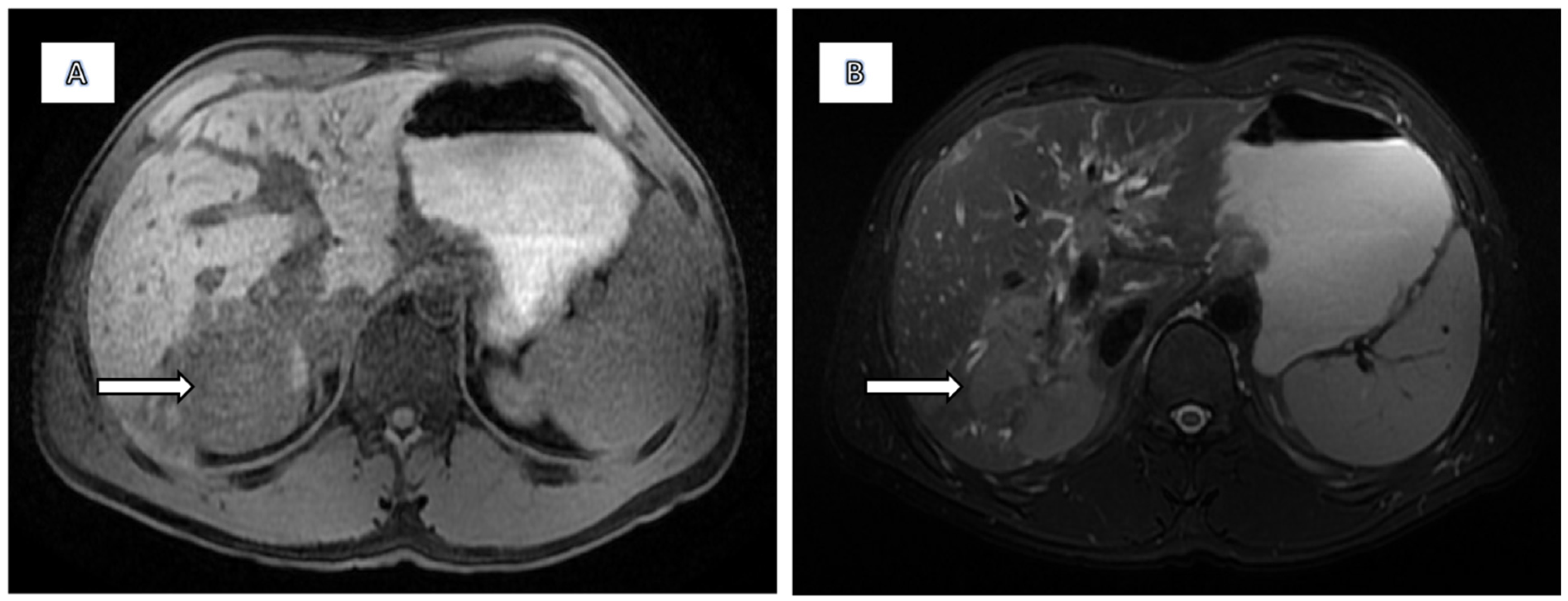

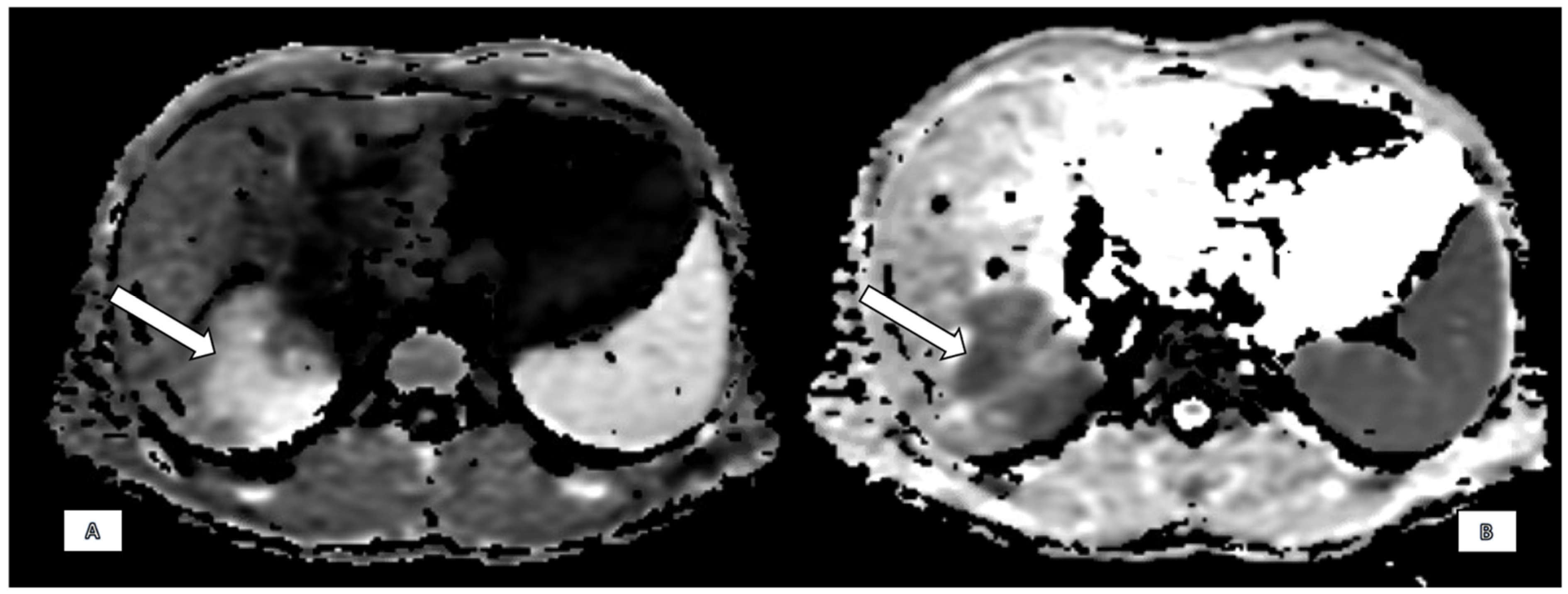

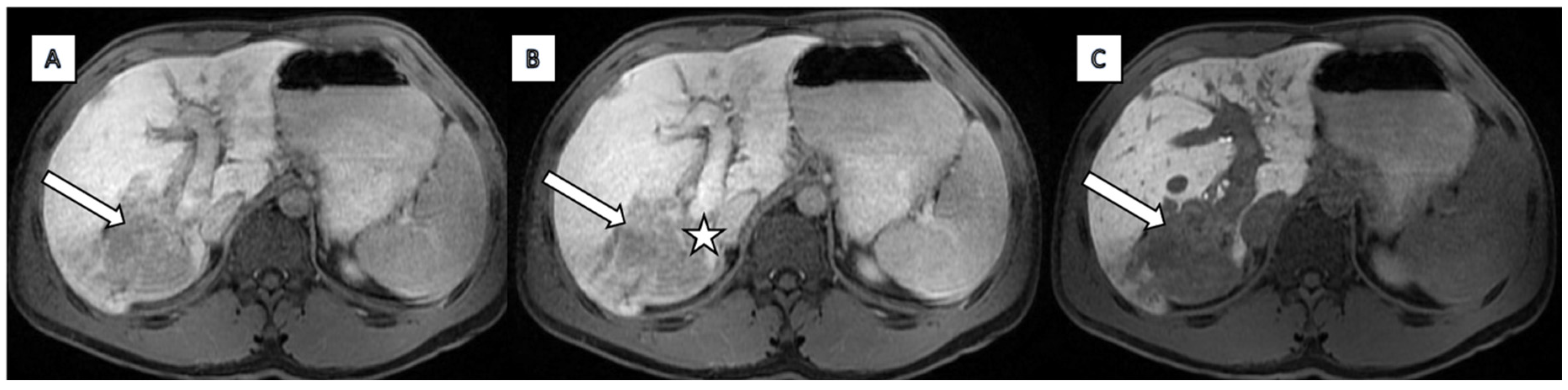

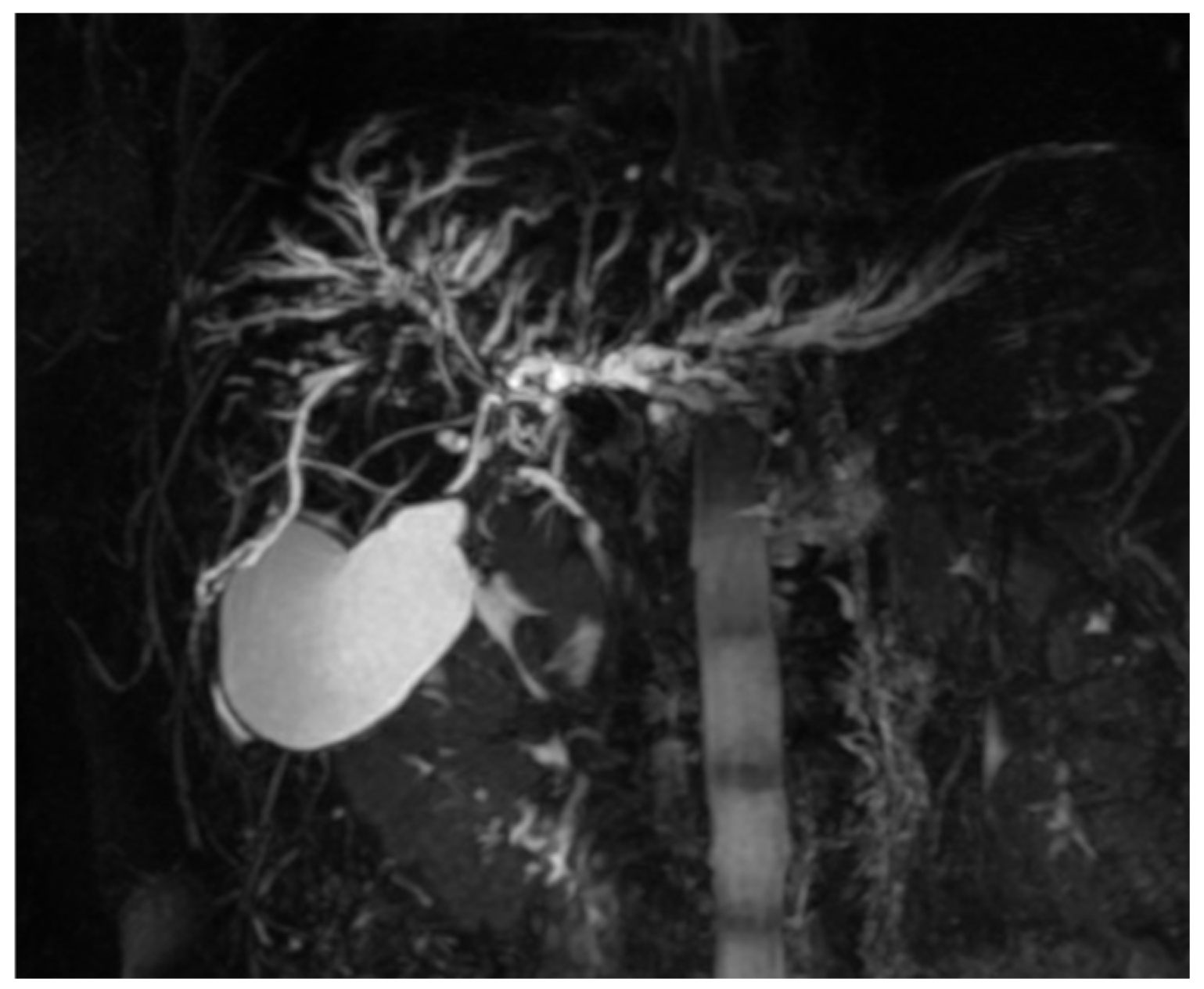

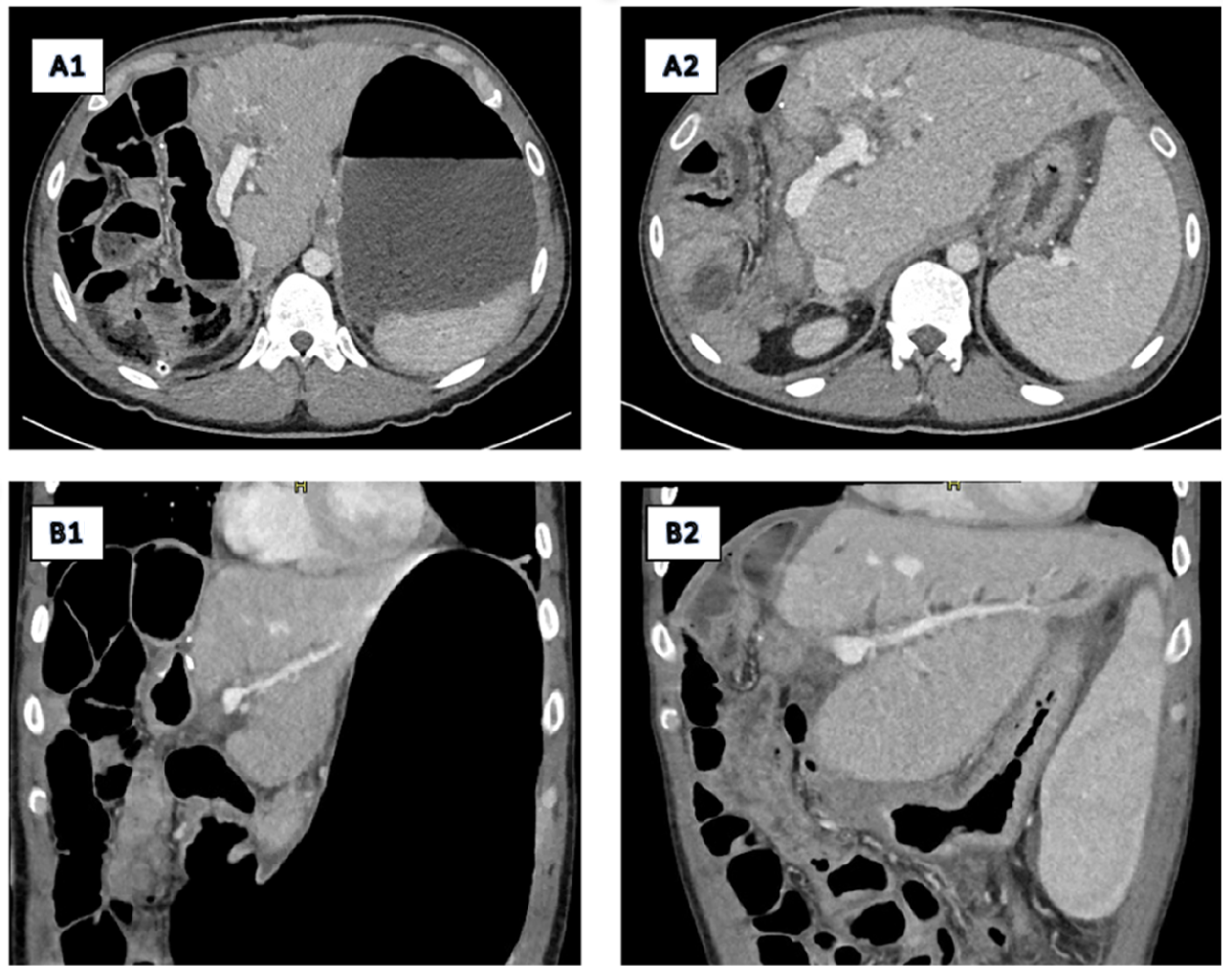

2.2. Imaging

2.3. Primary Surgery

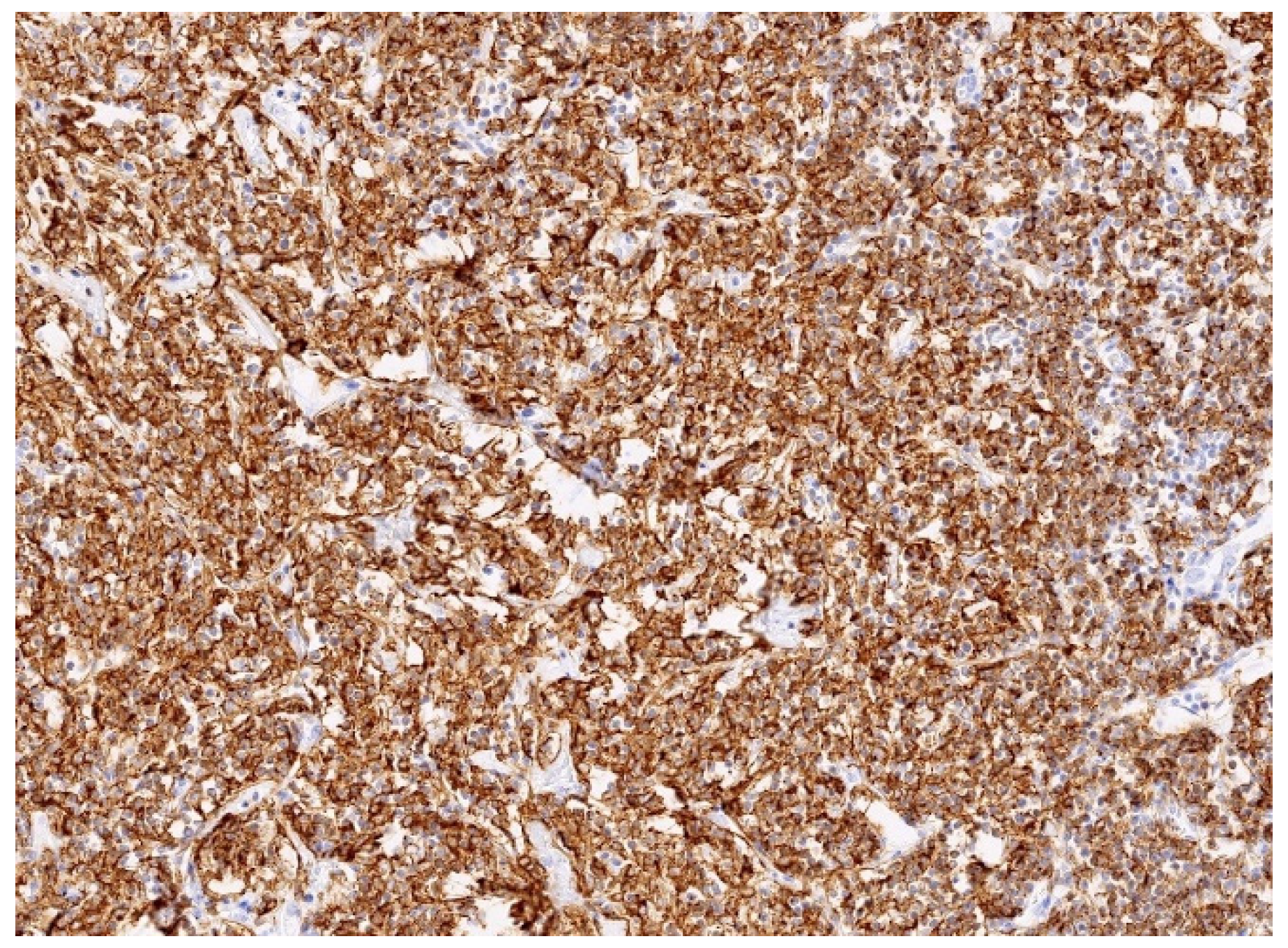

2.4. Pathology Findings

2.5. Postoperative Course, Liver Transplantation, and Follow-Up

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zucca, E.; Conconi, A.; Pedrinis, E.; Cortelazzato, S.; Motta, T.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Patterson, B.J.; Ferreri, A.J.M.; Ponzoni, M.; Devizzi, L.; et al. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood 2003, 101, 2489–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.W.; Tan, W.F.; Yu, W.L.; Shi, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Wu, M.-C. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphomas. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 6016–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Daou, R.; Bou Eid, J.; Fregonese, B.; El-Khoury, J.; Wijetunga, N.A.; Imber, B.S.; Yahalom, J.; Hajj, C. Management approaches for primary hepatic lymphoma: 10 year institutional experience with comprehensive literature review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1475118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamashita, Y.; Joshita, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Wakabayashi, S.; Sugiura, A.; Yamazaki, T.; Umemura, T. Primary hepatic extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in a patient with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Case report and summary of the literature. Medicina 2021, 57, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S.; Harimoto, N.; Kajiyama, K. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: A case report and literature review. Surg. Case Rep. 2015, 1, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlok, A.; De Grez, T.; Bouazza, F.; De Wind REl-Khoury, M.; Repullo, D.; Donckier, V. Primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking a hepatocellular carcinoma in a cirrhotic patient: Case report and systematic review of the lietarture. Case Rep. Surg. 2018, 10, 9183717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Su, Q. Primary hepatic lymphoma of MALT type mimicking hepatic adenoma treated by hepatectomy: A case report and litearture review. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1169455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiorah, I.E.; Johnson, L.; Ozdemirli, M. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the liver: A report of two cases and review of the literature. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okura, K.; Seo, S.; Shimizu, H.; Nishino, H.; Yoh, T.; Fukumitsu, K.; Ishii, T.; Hata, K.; Haga, H.; Hatano, E. Primary hepatic extranodal marginal zone B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated by laparoscopic partial hepatectomy: A case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Pang, C.; Sui, J.; Gao, Z. A case of primary hepatic extranodal marginal zone B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma treated by radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and a literature review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 300060521999539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Sakamoto, K.; Tokuhisa, Y.; Tokumitsu, Y.; Nakajima, M.; Matsukuma, S.; Matsui, H.; Shindo, Y.; Kanekiyo, S.; Suzuki, N.; et al. Two Cases of Primary Hepatic Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue(MALT) Lymphoma. Gan Kagaku Ryoho 2016, 43, 1794–1796. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khurana, A.; Mukherjee, U.; Patil, N. An unusual case of hepatic lymphoma with multiple epithelial malignancies. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2018, 61, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Lv, J.; Ji, Y.; Du, X.; Yang, X. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2019, 98, e15034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fu, Z.; Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, C.; Rao, Z.; Hu, S. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: Case report and literature review. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2021, 14, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doi, H.; Horiike, N.; Hiraoka, A.; Koizumi, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hasebe, A.; Ichikawa, S.; Yano, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; et al. Primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: Case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Hematol. 2008, 88, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, M.; Fang, H.; Xu, R. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and hemangioma with chronic hepatitis B virus infection as an underlying condition. Biosci. Trends 2014, 8, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X. Primary hepatic extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2017, 96, e6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, Y.D.; Kim, D.S.; Byun, G.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Suh, S.O. Primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma: A case report and review of the literature. Indian J. Surg. 2013, 75 (Suppl. S1), 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, M.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Suh, J.H.; Seo, M.J.; Cha, H.J. Primary hepatic extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2020, 54, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bronowicki, J.P.; Bineau, C.; Feugier, P.; Hermine, O.; Brousse, N.; Oberti, F.; Rousselet, M.C.; Dharancy, S.; Gaulard, P.; Flejou, J.F.; et al. Primary lymphoma of the liver: Clinical-pathological features and relationship with HCV infection in French patients. Hepatology 2003, 37, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Pan, F. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated B-cell lymphoma. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 1631–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, E.; Nakamura, M.; Satou, A.; Shimada, K.; Nakamura, S. Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma in the Gastrointestinal Tract in the Modern Era. Cancers 2022, 14, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Ponzoni, M. Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: Lessons from Western and Eastern diagnostic approaches. Pathology 2020, 52, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, P.G. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Semin. Hematol. 1999, 36, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, P.G.; Banks, P.M.; Best, P.V.; McLure, S.P.; Muller-Hermelink, H.K.; Wyatt, J.I. Primary low-grade hepatc B-cell lymphoma of mucossa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1995, 19, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, S.J.; Rosenberg, S.A. The natural history of initially untreated low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 311, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nart, D.; Ertan, Y.; Yilmaz, F.; Yuce, G.; Zeytunlu, M.; Kilic, M. Primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type in a liver transplant patient with hepatitis B cirrhosis. Transplant. Proc. 2005, 37, 4408–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, N.; Wei, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Kang, L. A Case of Primary Hepatic Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma in a Patient With Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Cureus 2024, 16, e65472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.Q.; Suriawinata, A.; Black, C.; Min, A.D.; Strauchen, J.; Thung, S.N. Primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2000, 124, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrego, M.; Guo, L.; Reeder, C.; De Petris, G.; Balan, V.; Douglas, D.D.; Byrne, T.; Harrison, E.; Mulligan, D.; Rodriguez-Luna, H.; et al. Hepatic B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of MALT type in the liver explant of a patient with chronic hepatitis C infection. Liver Transplant. 2005, 11, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forghani, F.; Masoodi, M.; Kadivar, M. Primary Hepatic Lymphoma Mimicking Cholangiocarcinoma. Oman Med. J. 2017, 32, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cho, Y.H.; Byun, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, M.G. Primary Malt Lymphoma of the Common Bile Duct. Korean J. Radiol. 2013, 14, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Claudon, M.; Dietrich, C.F.; Choi, B.I.; Cosgrove, D.O.; Kudo, M.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Piscaglia, F.; Wilson, S.R.; Barr, R.G.; Chammas, M.C.; et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver--update 2012: A WFUMB-EFSUMB initiative in cooperation with representatives of AFSUMB, AIUM, ASUM, FLAUS and ICUS. Ultraschall Med. 2013, 34, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiozawa, K.; Watanabe, M.; Ikehara, T.; Matsukiyo, Y.; Kikuchi, Y.; Kaneko, H.; Okubo, Y.; Shibuya, K.; Igarashi, Y.; Sumino, Y. A case of contiguous primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and hemangioma ultimately diagnosed using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Case Rep. Oncol. 2015, 8, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Foschi, F.G.; Dall’Aglio, A.C.; Marano, G.; Lanzi, A.; Savini, P.; Piscaglia, F.; Serra, C.; Cursaro, C.; Bernardi, M.; Andreone, P.; et al. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in primary hepatic lymphoma. J. Ultrasound Med. 2010, 29, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Novak, J.; Đokić, M.; Petrič, M.; Vozlič, D.; Živanović, M.; Ranković, B.; Trotovšek, B. Primary Hepatic Mucosa-Associated B-Cell Lymphoma in a Patient with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis—A Case Ultimately Requiring Liver Transplantation. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15162082

Novak J, Đokić M, Petrič M, Vozlič D, Živanović M, Ranković B, Trotovšek B. Primary Hepatic Mucosa-Associated B-Cell Lymphoma in a Patient with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis—A Case Ultimately Requiring Liver Transplantation. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(16):2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15162082

Chicago/Turabian StyleNovak, Jerica, Mihajlo Đokić, Miha Petrič, Diana Vozlič, Milanka Živanović, Branislava Ranković, and Blaž Trotovšek. 2025. "Primary Hepatic Mucosa-Associated B-Cell Lymphoma in a Patient with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis—A Case Ultimately Requiring Liver Transplantation" Diagnostics 15, no. 16: 2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15162082

APA StyleNovak, J., Đokić, M., Petrič, M., Vozlič, D., Živanović, M., Ranković, B., & Trotovšek, B. (2025). Primary Hepatic Mucosa-Associated B-Cell Lymphoma in a Patient with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis—A Case Ultimately Requiring Liver Transplantation. Diagnostics, 15(16), 2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15162082