Wearable Sensor–Based Gait Analysis in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: Quantitative Assessment of Residual Dizziness Using the φ-Bonacci Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Experimental Protocol

2.3. Data Acquisition

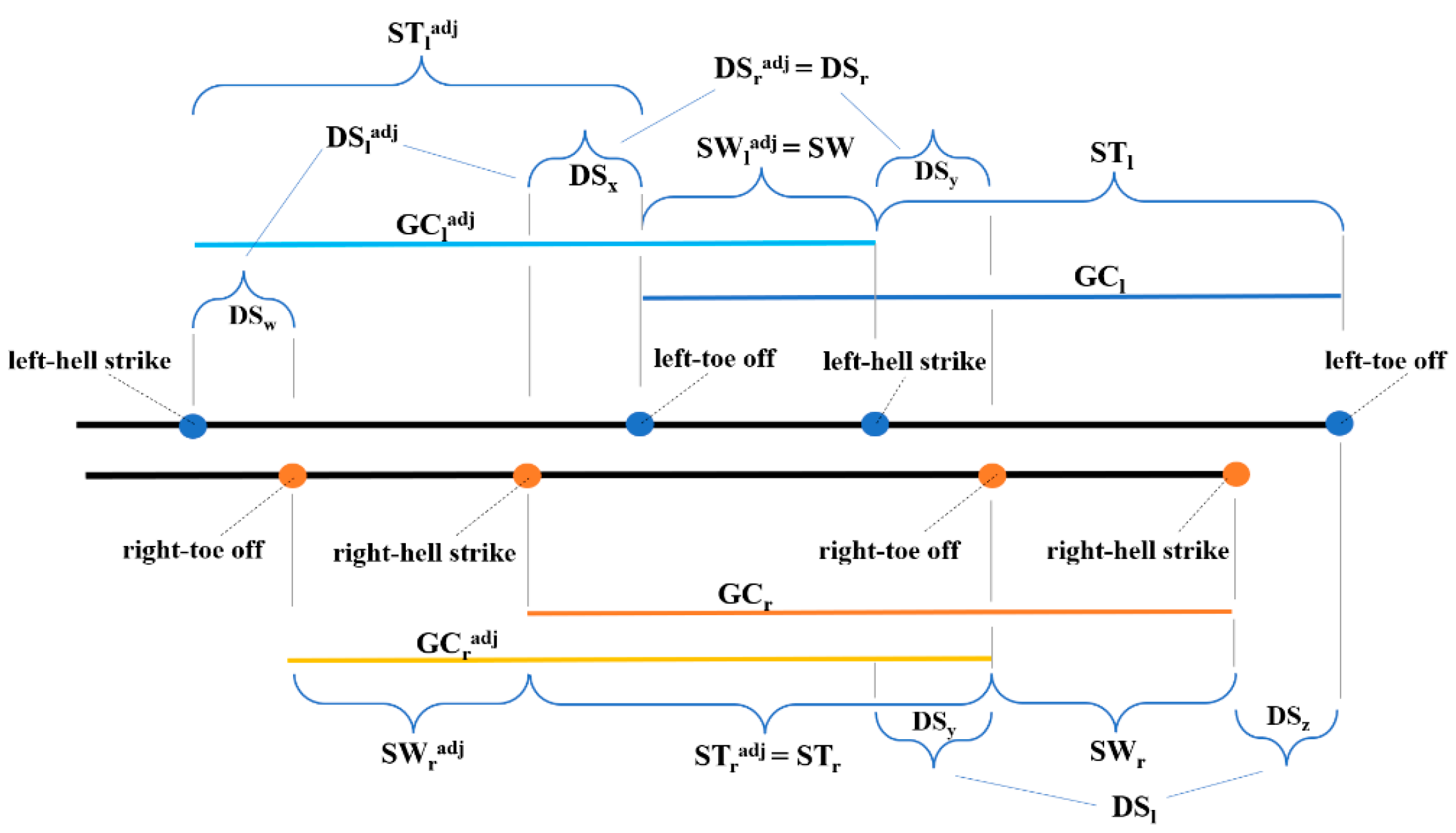

2.4. φ-Bonacci Gait Index Components

2.5. Signal Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

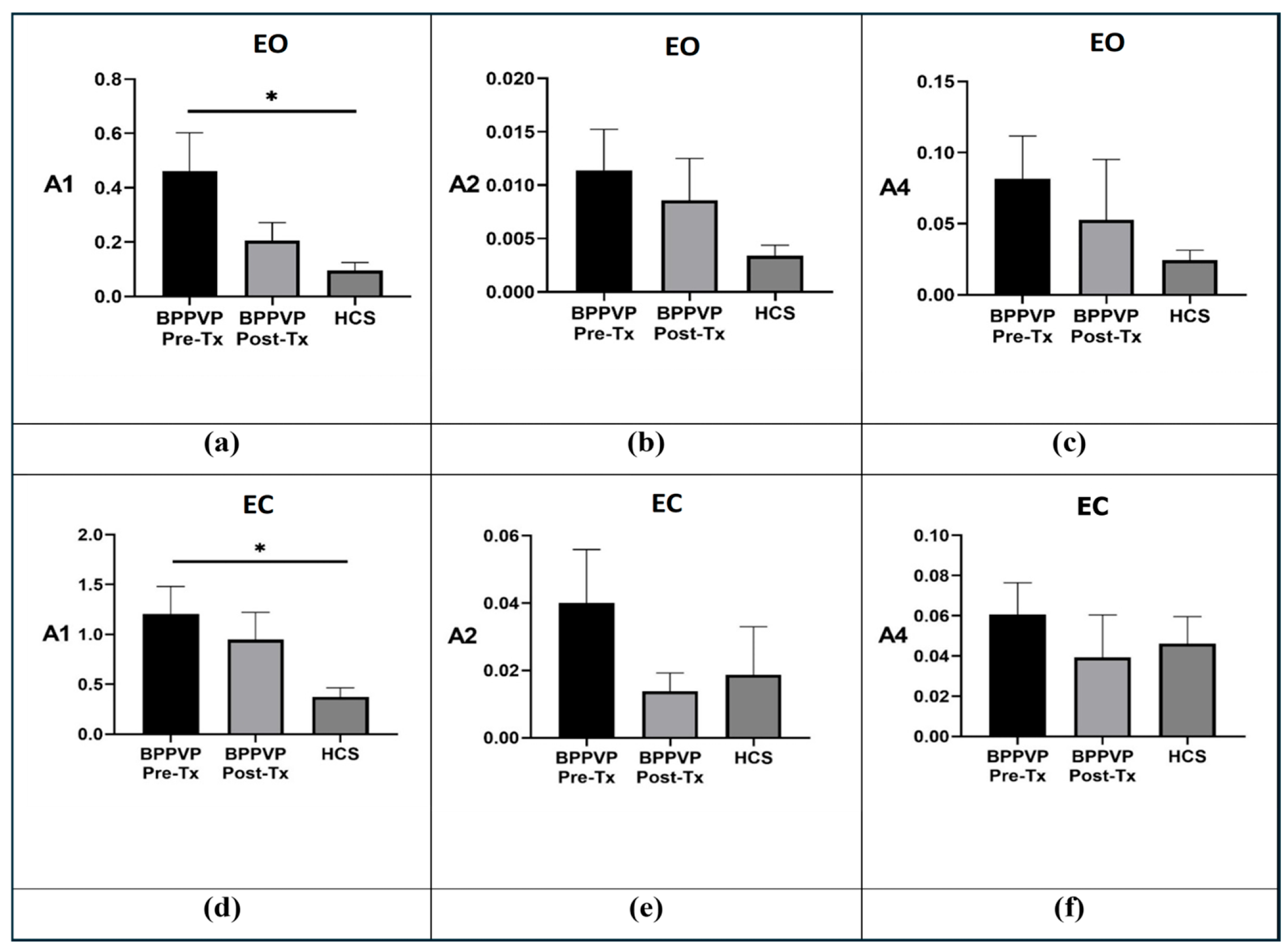

3.1. Groups Comparison

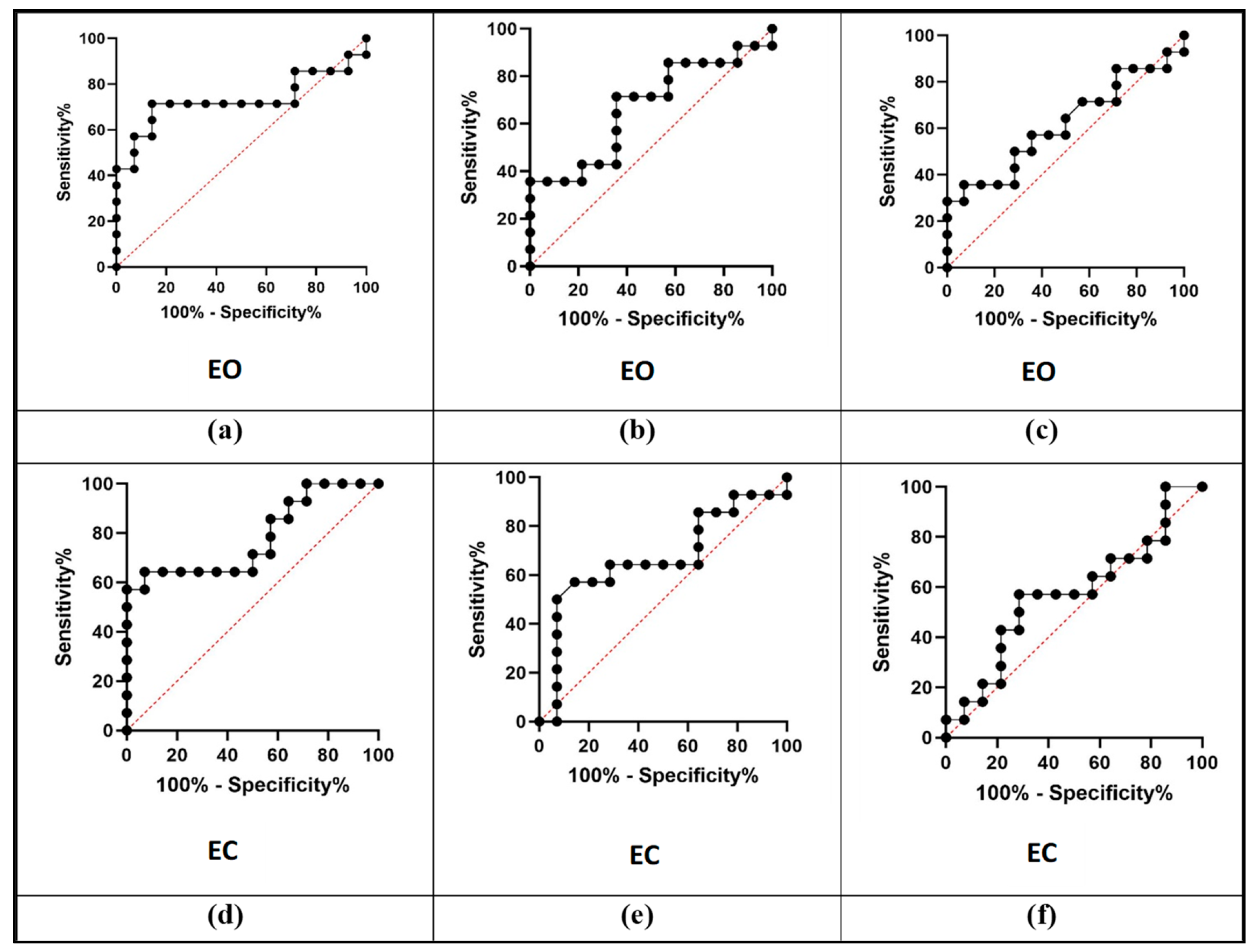

3.2. Diagnostic Performance Analysis

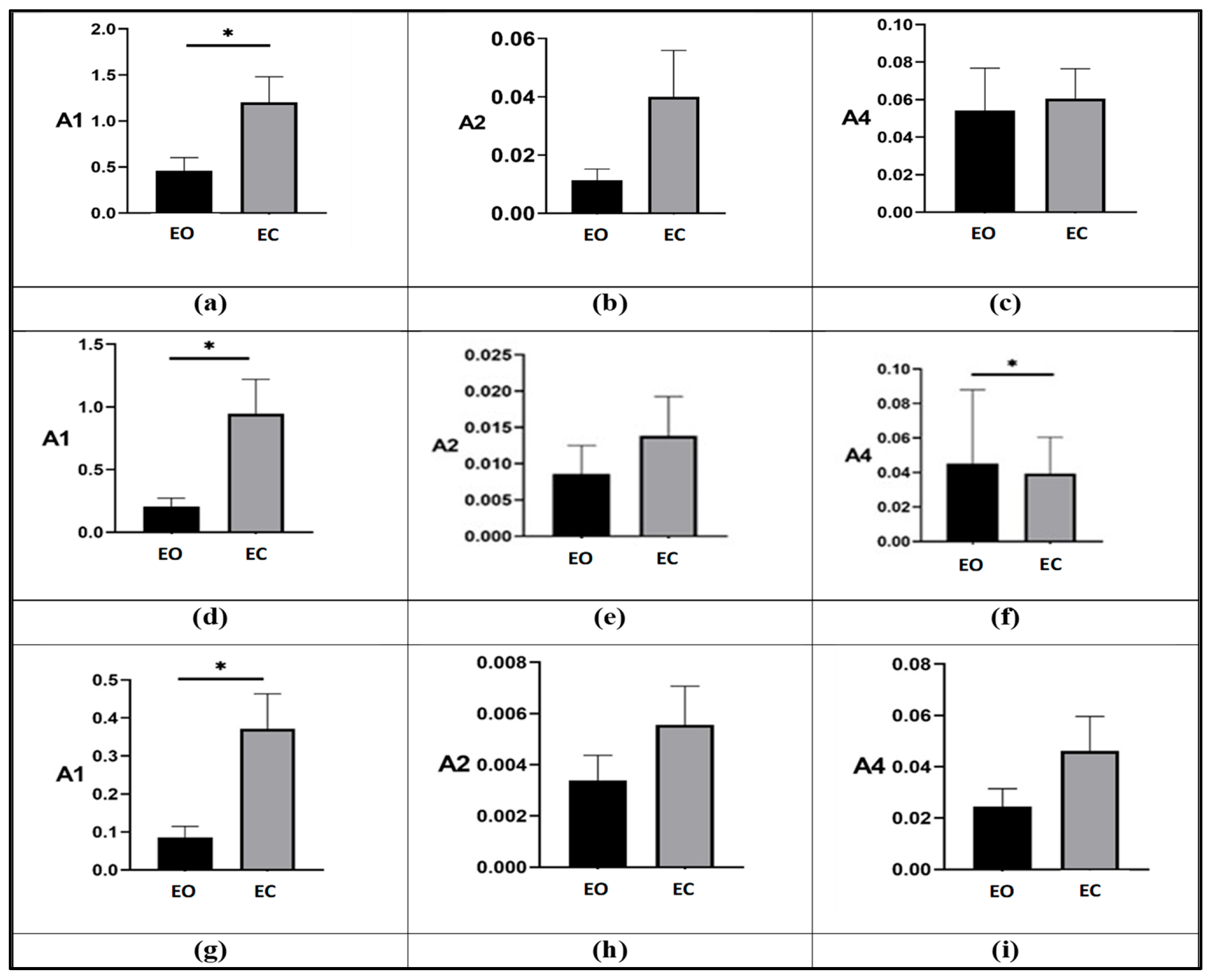

3.3. Effect of Visual Deprivation

3.4. Residual Dizziness Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| BPPV | Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo |

| BPPV-P | Patients with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo |

| HCS | Healthy Control Subjects |

| CRP | Canalith Repositioning Procedure |

| HIT | Head Impulse Test |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| EO | Eyes Open |

| EC | Eyes Closed |

| GC | Gait Cycle |

| HS | Heel Strike |

| TO | Toe Off |

| ST | Stance Phase |

| SW | Swing Phase |

| DS | Double Support Phase |

| adj | Adjoint Gait Cycle |

| Yφ | φ-Bonacci Gait Number |

| A1 | Self-Similarity Component |

| A2 | Swing Symmetry Component |

| A4 | Double-Support Consistency Component |

| Xn, Xd, Xv | Positive real quantities representing numerator (n), denominator (d), and value (v), used in the normalized computation of the φ-bonacci index |

| z1, z2, z3 | Time distances between the angular minima of the foot–tibia trajectory and the corresponding heel-strike or toe-off events |

| λ, δ, μadj, λadj, νconj | Weighting coefficients of the φ-bonacci index |

References

- Giacomini, P.G.; Alessandrini, M.; Magrini, A. Long-Term Postural Abnormalities in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. J. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Its Relat. Spec. 2002, 64, 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Martellucci, S.; Pagliuca, G.; De Vincentiis, M.; Greco, A.; De Virgilio, A.; Benedetti, F.M.N.; Gallipoli, C.; Rosato, C.; Clemenzi, V.; Gallo, A. Features of residual dizziness after canalith repositioning procedures for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özgirgin, O.N.; Kingma, H.; Manzari, L.; Lacour, M. Residual dizziness after BPPV management: Exploring pathophysiology and treatment beyond canalith repositioning maneuvers. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1382196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghislieri, M.; Gastaldi, L.; Pastorelli, S.; Tadano, S.; Agostini, V. Wearable Inertial Sensors to Assess Standing Balance: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Kim, B.; Park, S. Prediction of Lower Limb Kinetics and Kinematics during Walking by a Single IMU on the Lower Back Using Machine Learning. Sensors 2020, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, E.; Pineault, K.; Bair, W.; Studenski, S.; Agrawal, Y. Reduced vestibular function is associated with longer, slower steps in healthy adults during normal speed walking. Gait Posture 2019, 68, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Liu, S.-Y.; Cen, S.-S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, C.; Gu, Z.-Q.; Mao, W.; Ma, J.-H.; Zhou, Y.-T.; et al. Detection of motor dysfunction with wearable sensors in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 627481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizman, Y.; Tirosh, O.; Beh, J.; Fuss, F.K.; Pedell, S. Gait assessment using wearable sensor-based devices in neurological disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ling, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ren, K.; Chen, S.; Huang, P.; Tan, Y. Wearable sensor-based quantitative gait analysis in Parkinson’s disease patients with different motor subtypes. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Usefulness of mobile devices in the diagnosis and rehabilitation of balance disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelli, C.; Iosa, M.; Roselli, P.; Pisani, A.; Giannini, F.; Saggio, G. Generalized finite-length fibonacci sequences in healthy and pathological human walking: Comprehensively assessing recursivity, asymmetry, consistency, self-similarity, and variability of gaits. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 649533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelli, C.M.; Romagnoli, C.; Colistra, N.; Ferretti, I.; Annino, G.; Bonaiuto, V.; Manzi, V. Golden ratio and self-similarity in swimming: Breast-stroke and the back-stroke. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1176866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colistra, N.; Pietrosanti, L.; El Arayshi, M.; Maurantonio, S.; Francavilla, B.; Giacomini, P.; Verrelli, C. Comprehensive φ-bonacci index for walking ability assessment in paroxysmal positional vertigo: Role of rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics (ICINCO23), Rome, Italy, 13–15 November 2023; pp. 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Casali, D.; Paolizzo, F.; Alessandrini, M.; Micarelli, A.; Viziano, A.; Saggio, G. Towards the enhancement of body standing balance recovery by means of a wireless audio-biofeedback system. Med. Eng. Phys. 2018, 54, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Giannini, F.; Saggio, G.; Cenci, C.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Pisani, A. A novel analytical approach to assess dyskinesia in patients with Parkinson disease. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Rome, Italy, 11–13 June 2018; pp. 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Pisani, A.; Scalise, S.; Alwardat, M.; Salimei, C.; Giannini, F.; Saggio, G. Wearable electronics assess the effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation on balance and gait in Parkinson’s disease. Sensors 2019, 19, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Arayshi, M.; Verrelli, C.M.; Saggio, G.; Iosa, M.; Gentile, A.E.; Chessa, L.; Ruggieri, M.; Polizzi, A. Performance index for in-home assessment of motion abilities in ataxia telangiectasia: A pilot study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosa, M.; Morone, G.; Fusco, A.; Paolucci, S. Walking in the elderly: A systematic review on gait variability and the role of rehabilitation. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Verrelli, C.M.; Iosa, M.; Morone, G.; Saggio, G.; Paolucci, S. φ-bonacci gait index: A new approach for quantifying gait symmetry and consistency in neurological patients. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 669116. [Google Scholar]

- Iosa, M.; Fusco, A.; Marchetti, F.; Morone, G.; Caltagirone, C.; Paolucci, S.; Peppe, A. The golden ratio of gait harmony: Repetitive proportions of repetitive gait phases. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 918642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażkiewicz, M.; Wiszomirska, I.; Wit, A. Comparison of four methods of calculating the symmetry of spatial-temporal parameters of gait. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2014, 16, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novacheck, T.F. The biomechanics of running. Gait Posture 1998, 7, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, S.; Carender, W.; Wiens, J.; Sienko, K.H. Automatic ML-based vestibular gait classification: Examining the effects of IMU placement and gait task selection. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, H.; Hösl, M.; Schwameder, H.; Döderlein, L. A review on the clinical impact of wearable sensing and feedback systems for balance and gait rehabilitation. Gait Posture 2014, 40, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.B.; Lim, Y.Y.; Ng, W.Y.; Teo, W.P.; Tan, M.P. Quantitative gait analysis using wearable sensors in patients with vestibular disorders: Sensitivity to subtle postural and locomotor deficits. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 661249. [Google Scholar]

- Anson, E.R.; Edelman, S.; Gauchard, G.C.; Perrin, P. Use of wearable inertial sensors to evaluate gait and balance improvements after vestibular rehabilitation. Gait Posture 2019, 70, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Development and evaluation of a wearable force sensor system for improving postural control in elderly adults. Sensors 2015, 15, 22901–22917. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Wearable biofeedback systems for fall prevention: A pilot study on postural stability in older adults. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2016, 13, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Ghislieri, M.; Ricci, R.; Cappello, A.; Ferrarin, M. Validation of wearable inertial sensors for the assessment of postural sway during dynamic tasks. Sensors 2019, 19, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Li, S.; Liu, X. Exploring the Potentials of Wearable Technologies in Managing Vestibular Hypofunction. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martellucci, S.; Stolfa, A.; Castellucci, A.; Pagliuca, G.; Clemenzi, V.; Terenzi, V.; Malara, P.; Attanasio, G.; Gazia, F.; Gallo, A. Recovery of regular daily physical activities prevents residual dizziness after canalith repositioning procedures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 19, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teggi, R.; Albera, R.; Bussi, M. Residual dizziness after successful repositioning procedures: Clinical features and possible mechanisms. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2010, 30, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Staab, J.P.; Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Horii, A.; Jacob, R.; Strupp, M.; Brandt, T.; Bronstein, A. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): Consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J. Vestib. Res. 2017, 27, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francavilla, B.; Velletrani, G.; Chiaramonte, C.; Di Girolamo, S.; Giacomini, P.G. Assessing cognitive effort in Ménière’s disease: Pupillometry as a novel tool for postural control. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2024, 20, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yao, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Gu, D. Walking stability in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: An objective assessment using wearable accelerometers and machine learning. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museck, I.J.; Brinton, D.L.; Dean, J.C. The Use of Wearable Sensors and Machine Learning Methods to Estimate Biomechanical Characteristics During Standing Posture or Locomotion: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, S.; Carender, W.; Wiens, J.; Sienko, K.H. Automatically Classifying Vestibular Gait Using Timeseries Data from Wearable IMUs. Sensors 2024, 24, 7280. [Google Scholar]

- Won, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Moon, J.H. Machine Learning Strategies for LowCost InsoleBased CG Trajectory Estimation using Vertical Plantar Pressures. Sensors 2022, 22, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabi, C.E. Machine learning based risk of fall estimation using insole sensors. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2432515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Parameter | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Number of subjects | 15 BPPV-P, 15 HCS |

| Age (mean ± SD) | BPPV-P: 58.8 ± 5.3 yr; HCS: 59.4 ± 7.3 yr | |

| Sensor system | Platform | Movit System G1 (Captiks, Guidonia Montecelio, Italy) |

| Sensor modalities | 3D accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer, barometric sensor, quaternion fusion processor | |

| Degrees of freedom | 13 DOF per IMU | |

| Sampling rate | 200 Hz | |

| Wireless communication | USB-based wireless receiver | |

| Walking trials | EO condition | 20 m walk at self-selected comfortable speed |

| EC condition | 10 m walk at self-selected comfortable speed | |

| Trial duration | Distance covered at comfortable walking pace | |

| Data output | Extracted parameters | HS/TO timestamps (L/R), |

| Export format | CSV synchronized data | |

| Gait cycle analysis | Number of gait cycles analyzed | 1 composite gait cycle at midpoint of each trial |

| EO BPPV-P pre-tx | ||||||||

| A1 | A2 | A4 | ||||||

| 0.635 | 0.629 | 0.647 | 0.00102 | 0.00100 | 0.00104 | 0.00390 | 0.00400 | 0.00404 |

| 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.00006 | 0.00007 | 0.00007 | 0.00888 | 0.00900 | 0.00899 |

| 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.00335 | 0.00330 | 0.00341 | 0.00096 | 0.00010 | 0.00009 |

| 0.235 | 0.230 | 0.223 | 0.01051 | 0.01060 | 0.01021 | 0.07495 | 0.07160 | 0.06855 |

| 0.932 | 0.920 | 0.901 | 0.00346 | 0.00350 | 0.00341 | 0.03529 | 0.03660 | 0.03749 |

| 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.00057 | 0.00056 | 0.00054 | 0.01090 | 0.01090 | 0.01132 |

| 0.702 | 0.714 | 0.721 | 0.03175 | 0.03160 | 0.03312 | 0.21320 | 0.20580 | 0.20796 |

| 0.499 | 0.479 | 0.485 | 0.00664 | 0.00650 | 0.00671 | 0.03817 | 0.03890 | 0.03735 |

| 0.527 | 0.532 | 0.522 | 0.00267 | 0.00270 | 0.00279 | 0.02473 | 0.02590 | 0.02540 |

| 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.00140 | 0.00140 | 0.00143 | 0.11641 | 0.12200 | 0.12378 |

| 0.321 | 0.329 | 0.325 | 0.00271 | 0.00273 | 0.00266 | 0.00060 | 0.00060 | 0.00060 |

| 0.304 | 0.309 | 0.309 | 0.03596 | 0.03690 | 0.03867 | 0.31073 | 0.31540 | 0.30169 |

| 2.021 | 2.013 | 1.998 | 0.04020 | 0.04030 | 0.04200 | 0.00255 | 0.00250 | 0.00245 |

| 0.237 | 0.231 | 0.229 | 0.01898 | 0.01830 | 0.01801 | 0.30355 | 0.30100 | 0.30219 |

| 0.459 | 0.463 | 0.456 | 0.01140 | 0.01145 | 0.01170 | 0.08160 | 0.08190 | 0.08070 |

| EO BPPV-P post-tx | ||||||||

| A1 | A2 | A4 | ||||||

| 0.655 | 0.654 | 0.652 | 0.00008 | 0.00008 | 0.00008 | 0.00040 | 0.00040 | 0.00040 |

| 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.00087 | 0.00090 | 0.00086 | 0.00611 | 0.00600 | 0.00606 |

| 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.00328 | 0.00330 | 0.00316 | 0.00191 | 0.00190 | 0.00189 |

| 0.157 | 0.157 | 0.158 | 0.01864 | 0.01860 | 0.01859 | 0.08691 | 0.08450 | 0.08591 |

| 0.385 | 0.386 | 0.389 | 0.04357 | 0.04240 | 0.04351 | 0.59356 | 0.60000 | 0.61369 |

| 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.00061 | 0.00064 | 0.00063 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.00296 | 0.00300 | 0.00309 | 0.01540 | 0.01500 | 0.01546 |

| 0.151 | 0.149 | 0.151 | 0.00067 | 0.00069 | 0.00068 | 0.00101 | 0.00100 | 0.00101 |

| 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.00108 | 0.00105 | 0.00107 | 0.00170 | 0.00170 | 0.00184 |

| 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.00009 | 0.00009 | 0.00009 | 0.01177 | 0.01180 | 0.01119 |

| 0.470 | 0.471 | 0.480 | 0.00048 | 0.00047 | 0.00045 | 0.00010 | 0.00010 | 0.00010 |

| 0.065 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.00065 | 0.00065 | 0.00067 | 0.00767 | 0.00740 | 0.00759 |

| 0.701 | 0.683 | 0.678 | 0.04018 | 0.04030 | 0.04028 | 0.00069 | 0.00070 | 0.00068 |

| 0.252 | 0.254 | 0.256 | 0.00759 | 0.00776 | 0.00783 | 0.00685 | 0.00700 | 0.00690 |

| 0.206 | 0.205 | 0.206 | 0.00900 | 0.00895 | 0.00900 | 0.05350 | 0.05380 | 0.05410 |

| EO HCS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | A4 | ||||||

| 0.181 | 0.183 | 0.182 | 0.00900 | 0.00920 | 0.00940 | 0.04990 | 0.05090 | 0.05190 |

| 0.052 | 0.053 | 0.052 | 0.00084 | 0.00086 | 0.00088 | 0.00045 | 0.00047 | 0.00048 |

| 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.00013 | 0.00013 | 0.00014 | 0.05980 | 0.06060 | 0.06110 |

| 0.388 | 0.390 | 0.395 | 0.00069 | 0.00071 | 0.00072 | 0.00136 | 0.00140 | 0.00143 |

| 0.065 | 0.067 | 0.068 | 0.00595 | 0.0061 | 0.00625 | 0.06040 | 0.06170 | 0.06300 |

| 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.00940 | 0.00940 | 0.00960 | 0.07170 | 0.07390 | 0.07370 |

| 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.00189 | 0.00190 | 0.00194 | 0.0088 | 0.00900 | 0.00920 |

| 0.049 | 0.05 | 0.049 | 0.00009 | 0.00010 | 0.00010 | 0.0077 | 0.00790 | 0.00810 |

| 0.187 | 0.184 | 0.182 | 0.00068 | 0.00069 | 0.00071 | 0.0110 | 0.01130 | 0.01150 |

| 0.060 | 0.058 | 0.056 | 0.00367 | 0.0037 | 0.0037 | 0.00740 | 0.00760 | 0.00780 |

| 0.045 | 0.043 | 0.042 | 0.00226 | 0.0023 | 0.00235 | 0.0318 | 0.03220 | 0.03260 |

| 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.028 | 0.00970 | 0.0099 | 0.01010 | 0.0197 | 0.02010 | 0.02050 |

| 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.00077 | 0.00078 | 0.00079 | 0.00223 | 0.00230 | 0.00236 |

| 0.242 | 0.242 | 0.245 | 0.00166 | 0.00170 | 0.00174 | 0.00176 | 0.00180 | 0.00183 |

| 0.117 | 0.118 | 0.120 | 0.00307 | 0.00314 | 0.00320 | 0.02790 | 0.02831 | 0.02873 |

| Group | ΔA1 | ΔA2 | ΔA4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBPVP pre-tx | 419% | 213% | 48.6% |

| BBPVP post-tx | 1400% | 489% | 144% |

| HCS | 470% | 2.1% | 30% |

| A1 | A2 | A4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EO | EC | EO | EC | EO | EC | |

| No Residuals | 0.082 | 0.205 | 0.000795 | 0.0058 | 0.00145 | 0.00185 |

| Residual dizziness | 0.067 | 0.526 | 0.00105 | 0.007991 | 0.0017 | 0.0197 |

| Δ% | +22.38806 | −61.0266 | −24.2857 | −27.4183 | −14.7059 | −90.6091 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Francavilla, B.; Maurantonio, S.; Colistra, N.; Pietrosanti, L.; Balletta, D.; Omer, G.L.; Di Stadio, A.; Di Girolamo, S.; Verrelli, C.M.; Giacomini, P.G. Wearable Sensor–Based Gait Analysis in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: Quantitative Assessment of Residual Dizziness Using the φ-Bonacci Framework. Life 2026, 16, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010075

Francavilla B, Maurantonio S, Colistra N, Pietrosanti L, Balletta D, Omer GL, Di Stadio A, Di Girolamo S, Verrelli CM, Giacomini PG. Wearable Sensor–Based Gait Analysis in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: Quantitative Assessment of Residual Dizziness Using the φ-Bonacci Framework. Life. 2026; 16(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrancavilla, Beatrice, Sara Maurantonio, Nicolò Colistra, Luca Pietrosanti, Davide Balletta, Goran Latif Omer, Arianna Di Stadio, Stefano Di Girolamo, Cristiano Maria Verrelli, and Pier Giorgio Giacomini. 2026. "Wearable Sensor–Based Gait Analysis in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: Quantitative Assessment of Residual Dizziness Using the φ-Bonacci Framework" Life 16, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010075

APA StyleFrancavilla, B., Maurantonio, S., Colistra, N., Pietrosanti, L., Balletta, D., Omer, G. L., Di Stadio, A., Di Girolamo, S., Verrelli, C. M., & Giacomini, P. G. (2026). Wearable Sensor–Based Gait Analysis in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: Quantitative Assessment of Residual Dizziness Using the φ-Bonacci Framework. Life, 16(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010075