REGEN-COV as the First Line of Defense—A Single-Centre Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

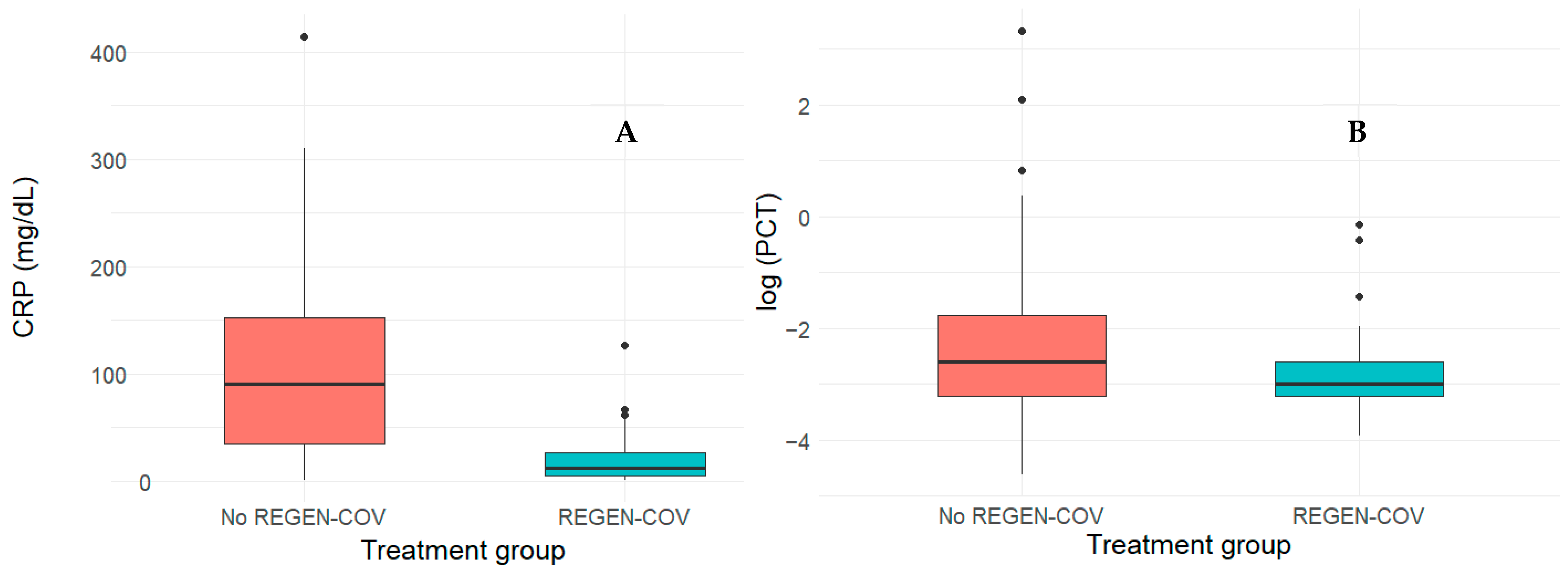

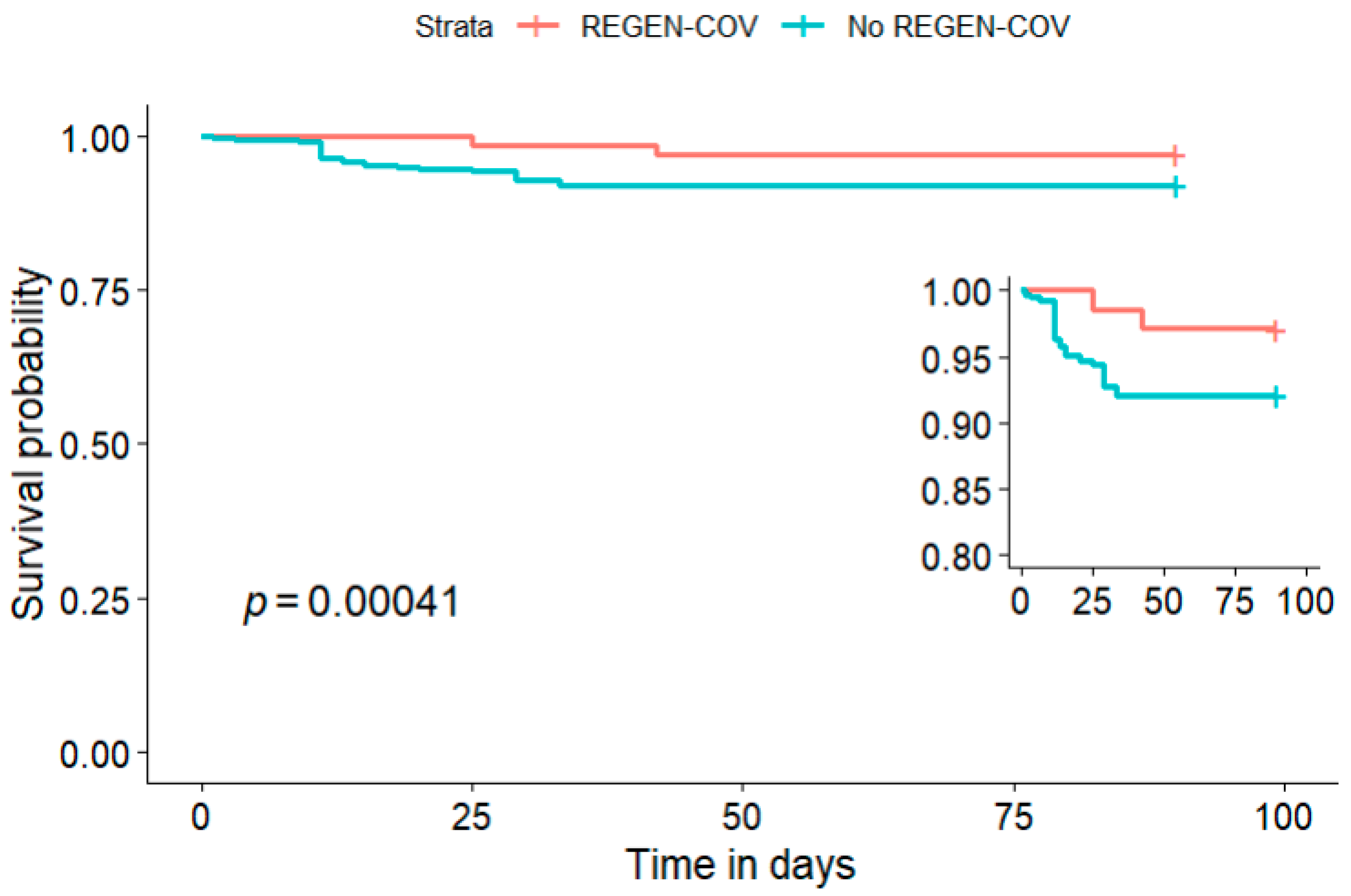

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographics

4.2. Comparison of REGEN-COV and Non-REGEN-COV Groups

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| CRP | C-reactive Protein |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

References

- COVID-19 Cases|WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Onder, G.; Rezza, G.; Brusaferro, S. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1775–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Lippi, G. COVID-19 Mortality Trends over the First Five Years of the Pandemic in the US. COVID 2025, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Graff, J.C.; Aleya, L.; Ma, J.; Cao, Y.; Wei, W.; Sun, S.; Wang, C.; Jiao, Y.; Gu, W.; et al. Mortality in Four Waves of COVID-19 Is Differently Associated with Healthcare Capacities Affected by Economic Disparities. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Saussez, S. Importance of Epidemiological Factors in the Evaluation of Transmissibility and Clinical Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.C.; Adams, A.C.; Hufford, M.M.; de la Torre, I.; Winthrop, K.; Gottlieb, R.L. Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zost, S.J.; Gilchuk, P.; Case, J.B.; Binshtein, E.; Chen, R.E.; Nkolola, J.P.; Schäfer, A.; Reidy, J.X.; Trivette, A.; Nargi, R.S.; et al. Potently Neutralizing and Protective Human Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 584, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Shan, C.; Duan, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Song, J.; Song, T.; Bi, X.; Han, C.; Wu, L.; et al. A Human Neutralizing Antibody Targets the Receptor-Binding Site of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 584, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Rodríguez, Y.; Monsalve, D.M.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y.; Camacho, B.; Gallo, J.E.; Rojas-Villarraga, A.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Díaz-Coronado, J.C.; Manrique, R.; et al. Convalescent Plasma in COVID-19: Possible Mechanisms of Action. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.K.P.; Suwanmanee, S.; Casadevall, A.; Shoham, S.; Bloch, E.M.; Gebo, K.A.; Tobian, A.A.R.; Pekosz, A.; Klein, S.L.; Sullivan, D.; et al. The Effect of Early COVID-19 Treatment with Convalescent Plasma on Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e03006-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzberger, N.; Hirsch, C.; Chai, K.L.; Tomlinson, E.; Khosravi, Z.; Popp, M.; Neidhardt, M.; Piechotta, V.; Salomon, S.; Valk, S.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-Neutralising Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD013825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, E.D. Casirivimab/Imdevimab: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group Casirivimab and Imdevimab in Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Platform Trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 665–676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreich, D.M.; Sivapalasingam, S.; Norton, T.; Ali, S.; Gao, H.; Bhore, R.; Xiao, J.; Hooper, A.T.; Hamilton, J.D.; Musser, B.J.; et al. REGEN-COV Antibody Combination and Outcomes in Outpatients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtani, M.; Yokoo, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Yasuda, H.; Nishikawa, E.; Tomida, M.; Tsukada, M.; Sato, E.; Hirayama, S.; Murakami, H.; et al. Clinical Efficacy of Casirivimab and Imdevimab in Preventing COVID-19 in the Omicron BA.5 Subvariant Epidemic: A Retrospective Study. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2025, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, D.; Bruel, T.; Staropoli, I.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Porrot, F.; Maes, P.; Grzelak, L.; Prot, M.; Mougari, S.; Planchais, C.; et al. Resistance of Omicron Subvariants BA.2.75.2, BA.4.6, and BQ.1.1 to Neutralizing Antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawazi, S.M.; Khan, J.; Othman, N.; Alolayan, S.O.; Alahmadi, Y.M.; Thagfan, S.S.A.; Helmy, S.A.; Marzo, R.R. Regen-Cov and COVID-19, Update on the Drug Profile and Fda Status: A Mini-Review and Bibliometric Study. J. Public. Health Res. 2022, 10, jphr.2021.2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-D.; Ding, M.; Dong, X.; Zhang, J.-J.; Kursat Azkur, A.; Azkur, D.; Gan, H.; Sun, Y.-L.; Fu, W.; Li, W.; et al. Risk Factors for Severe and Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients: A Review. Allergy 2021, 76, 428–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Zhu, J.; Ji, P.; Li, H.; Zhong, Z.; Li, B.; Pang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, X. Risk Factors of Severe Cases with COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Greco, M.; Zanella, A.; Albano, G.; Antonelli, M.; Bellani, G.; Bonanomi, E.; Cabrini, L.; Carlesso, E.; Castelli, G.; et al. Risk Factors Associated With Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 in Intensive Care Units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Horo, J.; Challener, D.W.; Anderson, R.J.; Arndt, R.F.; Ausman, S.E.; Hall, S.T.; Heyliger, A.; Kennedy, B.D.; Sweeten, P.W.; Ganesh, R.; et al. Rates of Severe Outcomes After Bamlanivimab-Etesevimab and Casirivimab-Imdevimab Treatment of High-Risk Patients With Mild to Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahey, G.M.; McDonald, E.; Marshall, K.; Martin, S.W.; Chun, H.; Herlihy, R.; Tate, J.E.; Kawasaki, B.; Midgley, C.M.; Alden, N.; et al. Risk Factors for Hospitalization among Persons with COVID-19-Colorado. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagan, N.; Barda, N.; Kepten, E.; Miron, O.; Perchik, S.; Katz, M.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Reis, B.; Balicer, R.D. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arikawa, S.; Fukuoka, K.; Nakamoto, K.; Kunitomo, R.; Matsuno, Y.; Shimazaki, T.; Saraya, T.; Kawakami, T.; Kishimoto, M.; Komagata, Y.; et al. Effectiveness of Neutralizing Antibody Cocktail in Hemodialysis Patients: A Case Series of 20 Patients Treated with or without REGN-COV2. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2022, 26, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenzato, L.; Botton, J.; Drouin, J.; Cuenot, F.; Dray-Spira, R.; Weill, A.; Zureik, M. Chronic Diseases, Health Conditions and Risk of COVID-19-Related Hospitalization and in-Hospital Mortality during the First Wave of the Epidemic in France: A Cohort Study of 66 Million People. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 8, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, R.; Philpot, L.M.; Bierle, D.M.; Anderson, R.J.; Arndt, L.L.; Arndt, R.F.; Culbertson, T.L.; Destro Borgen, M.J.; Hanson, S.N.; Kennedy, B.D.; et al. Real-World Clinical Outcomes of Bamlanivimab and Casirivimab-Imdevimab Among High-Risk Patients With Mild to Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verderese, J.P.; Stepanova, M.; Lam, B.; Racila, A.; Kolacevski, A.; Allen, D.; Hodson, E.; Aslani-Amoli, B.; Homeyer, M.; Stanmyre, S.; et al. Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibody Treatment Reduces Hospitalization for Mild and Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Real-World Experience. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, L.; Elders, T.; Werhane, L.; Korwek, K.; Poland, R.; Guy, J. Reactions and COVID-19 Disease Progression Following SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibody Infusion. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 112, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutoh, Y.; Umemura, T.; Ota, A.; Okuda, K.; Moriya, R.; Tago, M.; Soejima, K.; Noguchi, Y.; Bando, T.; Ota, S.; et al. Effectiveness of Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for COVID-19 Patients Using a Risk Scoring System. J. Infect. Chemother. 2022, 28, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Azañedo, D.; Vargas-Fernández, R.; Bendezu-Quispe, G. Association of Comorbidities With Pneumonia and Death Among COVID-19 Patients in Mexico: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. J. Prev. Med. Public. Health 2020, 53, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, A.; Marshall, S.; Ogasawara, T.; Ogasawara, T.; Aoka, Y.; Sakura, H.; Uchigata, Y.; Ogawa, T. REGN-COV2 Antibody Cocktail in Patients with SARS-CoV-2: Observational Study from a Single Institution in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2022, 28, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, D.; Popović, M.; Banjac, M.; Bulajić, J.; Đurović, V.; Urošević, I.; Milovančev, A. Outcomes in COVID-19 Patients with Pneumonia Treated with High-Flow Oxygen Therapy and Baricitinib—Retrospective Single-Center Study. Life 2023, 13, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.T.; McCreary, E.K.; Bariola, J.R.; Minnier, T.E.; Wadas, R.J.; Shovel, J.A.; Albin, D.; Marroquin, O.C.; Kip, K.E.; Collins, K.; et al. Effectiveness of Casirivimab-Imdevimab and Sotrovimab During a SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant Surge. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2220957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, K.E.; McCreary, E.K.; Collins, K.; Minnier, T.E.; Snyder, G.M.; Garrard, W.; McKibben, J.C.; Yealy, D.M.; Seymour, C.W.; Huang, D.T.; et al. Evolving Real-World Effectiveness of Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakinoki, Y.; Yamada, K.; Tanino, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Suzuki, N.; Asari, G.; Nakamura, A.; Kukita, S.; Uehara, A.; et al. Impact of Antibody Cocktail Therapy Combined with Casirivimab and Imdevimab on Clinical Outcome for Patients with COVID-19 in A Real-Life Setting: A Single Institute Analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 117, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, S.; Ben-shlomo, Y.; Dagan, N.; Reis, B.Y.; Barda, N.; Kepten, E.; Roitman, A.; Shapira, S.; Yaron, S.; Balicer, R.D.; et al. Effectiveness of REGEN-COV Antibody Combination in Preventing Severe COVID-19 Outcomes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Overall, N = 206 1 | REGEN-COV, N = 69 1 | Non-REGEN-COV, N = 137 1 | p-Value 4 | SMD 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64 (50–71) | 58 (45–71) | 65 (54–71) | 0.037 | 0.0021 |

| Sex (male) | 120 (58) | 37 (54) | 83 (61) | 0.339 | 0.0956 |

| Time from symptom onset to presentation (days) 3 | 6 (3–9) | 3 (2–4) | 8 (6–10) | <0.001 | |

| Vaccinated | 78 (38) | 32 (46) | 45 (33) | 0.036 | −0.0120 |

| Number of comorbidities ≥ 2 | 143 (69) | 54 (78) | 89 (65) | 0.051 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 (17) | 1 (1.4) | 35 (26) | <0.001 | 0.0175 |

| Hypertension | 147 (71) | 44 (64) | 103 (75) | 0.087 | 0.0696 |

| Pneumonia | 133 (65) | 16 (23) | 117 (85) | <0.001 | −0.0159 |

| Parameter | Overall, N = 206 1 | Hospitalized, N = 128 1 | Non-hospitalized, N = 78 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64 (50, 71) | 66 (54, 71) | 60 (42, 71) | 0.015 |

| Sex (male) | 120 (58) | 75 (59) | 45 (58) | 0.899 |

| Vaccinated | 78 (38) | 39 (30) | 39 (50) | 0.005 |

| Number of comorbidities ≥ 2 | 143 (69) | 87 (68) | 56 (72) | 0.563 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 (18) | 31 (24) | 6 (7.7) | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 147 (71) | 98 (77) | 49 (63) | 0.034 |

| Pneumonia | 73 (35) | 4 (3.1) | 69 (88) | <0.001 |

| Parameter | Overall, N = 206 1 | REGEN-COV, N = 69 1 | Non-REGEN-COV, N = 137 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalized | 128 (62) | 11 (16) | 117 (85) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospitalization (days) | 12 (9–16) | 11 (9–15) | 12 (9–16) | 0.932 |

| ICU ward admission | 25 (13) | 1 (1.4) | 24 (18) | <0.001 |

| Death | 32 (17) | 2 (2.9) | 30 (22) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Popović, M.; Đurović, V.; Ljubičić, B.; Kovačević, N.; Šajinović, S.; Petrović, L.; Ilić, T.; Golubović, S. REGEN-COV as the First Line of Defense—A Single-Centre Experience. Life 2026, 16, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010074

Popović M, Đurović V, Ljubičić B, Kovačević N, Šajinović S, Petrović L, Ilić T, Golubović S. REGEN-COV as the First Line of Defense—A Single-Centre Experience. Life. 2026; 16(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010074

Chicago/Turabian StylePopović, Milica, Vladimir Đurović, Bojana Ljubičić, Nadica Kovačević, Slobodan Šajinović, Lada Petrović, Tatjana Ilić, and Sonja Golubović. 2026. "REGEN-COV as the First Line of Defense—A Single-Centre Experience" Life 16, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010074

APA StylePopović, M., Đurović, V., Ljubičić, B., Kovačević, N., Šajinović, S., Petrović, L., Ilić, T., & Golubović, S. (2026). REGEN-COV as the First Line of Defense—A Single-Centre Experience. Life, 16(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010074