4.1. Comparison with Literature

Radiotherapy is well known to induce both structural and functional vascular alterations through endothelial injury, inflammatory activation, and progressive fibrotic remodeling. The observed difference in histological type between tumor sites reflects established tumor biology rather than a novel finding, and was therefore not further explored as an independent predictor of perioperative outcomes. Several studies have shown that ionizing radiation triggers endothelial dysfunction, microthrombosis, and perivascular fibrosis, ultimately accelerating atherosclerosis and contributing to vessel wall fragility over time [

7,

8]. This mechanism aligns with the histopathological findings in our pelvic cohort, where perivascular fibrosis and inflammatory thrombus were frequent, despite no significant increase in major vascular injuries.

Similar vascular changes have been described across other anatomical regions, particularly the head, neck, and mediastinum. Both historical and contemporary reports document periarterial fibrosis and chronic thrombosis, occasionally associated with delayed stenoses or strictures, even in the absence of recurrent disease [

2,

9]. This pattern supports the concept of a fibrotic vascular signature characteristic of irradiated tissues. Among the factors analyzed, cervical tumor site and perivascular fibrosis were associated with a higher surgical risk, supporting the role of radiation-induced tissue changes rather than overt vascular injury.

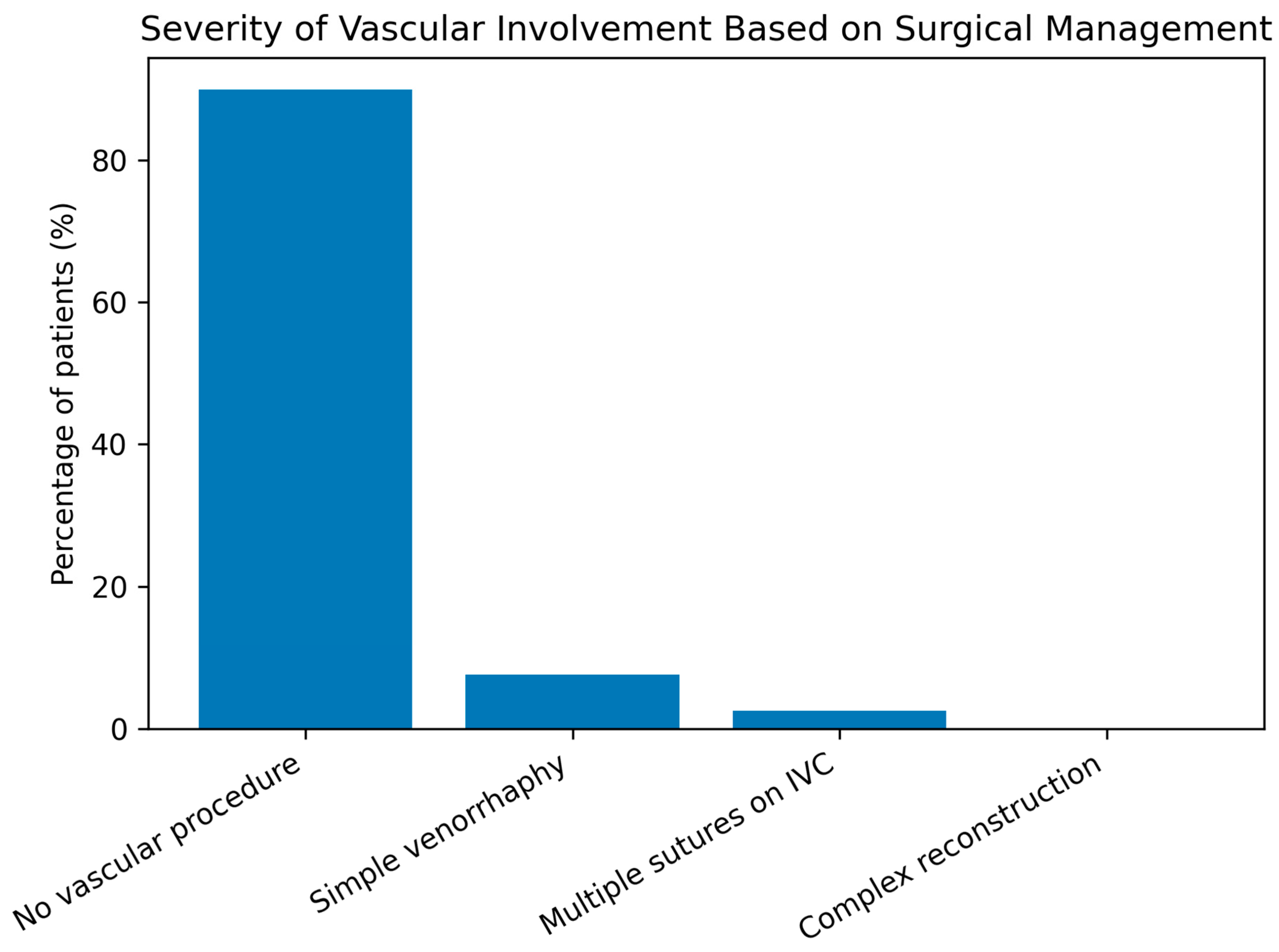

Surgically, irradiated fields are recognized as technically challenging because of dense fibrosis, loss of dissection planes, and increased friability However, the literature indicates that complex vascular reconstructions are rarely required in irradiated fields, as most intraoperative vascular issues can be managed conservatively or with simple surgical repair, such as venorrhaphy [

9]. When used, intraoperative venography serves as a diagnostic tool to guide immediate decision-making rather than as a corrective intervention. Our results parallel these findings, with a low rate of vascular reconstruction despite frequent perivascular changes.

Cardio-oncology studies further highlight that perioperative morbidity is increased in irradiated patients, driven largely by tissue fragility and hemorrhagic risk rather than by overt vascular injury [

8,

10]. This is consistent with our finding of a higher complication rate in cervical cancer patients, likely reflecting altered tissue quality rather than macrovascular events.

Large vessel complications after RT, such as stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm, are well documented but tend to occur later and are strongly influenced by dose, field, and latency [

11]. Ophthalmic and neurovascular series show that radiation-associated occlusive events may arise years or decades after treatment, often accompanied by extensive collateral formation [

12,

13,

14]. Pediatric studies, including proton radiotherapy cohorts, report moyamoya-like vasculopathy in 6–7% of patients after several years, emphasizing that macrovascular events are selective and delayed, whereas early changes are predominantly microvascular and fibrotic [

15].

From an ophthalmologic perspective, post-radiation retinopathy further illustrates this chronology. Occlusive capillaropathy and ischemia typically develop after long latency, especially at higher doses, while choroidal histology reveals hyalinization, ectasia, and pathologic neovascularization [

16,

17]. Similar mechanisms likely underlie the fibrotic, friable vascular tissue encountered intraoperatively in the pelvis.

Experimental and translational studies reinforce this model. NF-κB–driven inflammatory signaling, oxidative stress, and intimal hyperplasia have been implicated in radiation-induced vascular injury [

18,

19]. Genetic susceptibility may also modulate risk, although no single determinant has been identified [

20].

Management strategies reported in neurovascular literature emphasize a tailored, minimally invasive approach. Endovascular techniques are often preferred over open repair because of poor tissue planes and fragility [

2,

21]. This is fully consistent with our experience, where no major vascular reconstructions were required. Additionally, adjuvant factors such as cisplatin therapy may potentiate vascular inflammation, as illustrated in leukocytoclastic vasculitis case reports [

22].

Our pelvic cohort mirrors the well-characterized vascular signature of post-radiation injury—endothelial dysfunction, perivascular fibrosis, and inflammatory thrombosis—described across neurovascular, head-and-neck, and mediastinal series. Despite frequent local vascular changes, major intraoperative vascular reconstructions were rarely required. The higher perioperative complication rate in cervical cancer patients likely reflects tissue quality changes rather than overt macrovascular injury. These findings align with literature showing that early radiation effects are predominantly microvascular and fibrotic, while major occlusive events are selective and delayed, and with evidence implicating NF-κB–driven chronic inflammation and dose-dependent tissue fragility.

4.2. Mechanisms of Complications

Radiotherapy induces a complex cascade of vascular injury involving endothelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, microthrombosis, and progressive fibrotic remodeling, which together increase perioperative morbidity even in the absence of overt macrovascular lesions [

23].

Ionizing radiation causes direct damage to endothelial cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activation of inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB, leading to increased vascular permeability, exposure of subendothelial structures, and activation of the coagulation cascade. This endothelial dysfunction sets the stage for local thrombosis and chronic vascular remodeling [

18,

19].

Radiation injury is not limited to an acute effect but triggers a chronic inflammatory response sustained by macrophages, lymphocytes, and profibrotic mediators such as TGF-β and VEGF. This leads to intimal thickening, perivascular collagen deposition, and fibrotic transformation of the vessel wall. Intraoperatively, these processes manifest as fibrotic, adherent, and poorly dissectible vessels [

14,

24].

Endothelial injury promotes the expression of adhesion molecules, platelet activation, and fibrin deposition, resulting in inflammatory microthrombi in small and medium vessels. These changes can increase perioperative bleeding risk, local tissue ischemia, and impaired wound healing even when no major vascular lesion is present [

8,

12,

25].

Chronic remodeling ultimately leads to perivascular fibrosis, loss of normal anatomical planes, and increased vessel wall fragility. These features make dissection technically challenging and increase the risk of intraoperative vascular injury without a proportional rise in major vascular reconstruction rates [

2,

9,

26].

Over time, these mechanisms can lead to progressive stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm formation in irradiated vessels. Such events typically occur years to decades after treatment and are strongly influenced by radiation dose, field, and latency [

15,

21].

Systemic factors further modulate these vascular changes. Cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy has been associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, reflecting an exacerbation of vascular inflammation [

22,

27]. Classical cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking) and genetic susceptibility may also increase vulnerability to radiation vasculopathy [

20,

28].

Perioperative morbidity is increased in irradiated patients because fibrosis makes vessels fragile and adherent, microthrombotic changes impair hemostasis and wound healing, and major vascular complications typically occur in a delayed rather than immediate perioperative phase [

29].

This pathophysiological framework is consistent with our finding of increased perioperative complications but low rates of vascular reconstruction, and underscores the need for tailored surgical planning and multidisciplinary perioperative management.

4.3. Clinical Implications

The vascular and perivascular changes induced by radiotherapy have significant surgical and perioperative consequences. Even in the absence of major vascular stenosis or occlusion, irradiated tissues demonstrate increased fragility, altered anatomical planes, and a prothrombotic and proinflammatory environment, all of which can influence the safety and complexity of pelvic oncologic surgery.

Although individual patient characteristics such as comorbidities, functional status, and lifestyle factors are important determinants of surgical risk, these data were not uniformly available in this retrospective cohort. In this context, tumor site and intraoperative markers of radiation-induced tissue damage, such as perivascular fibrosis, represent practical and readily identifiable indicators of increased surgical risk.

Fibrotic remodeling and loss of normal tissue planes make dissections technically challenging, leading to increased intraoperative bleeding, a higher risk of inadvertent vascular injury, and more difficult hemostasis in irradiated fields [

30]. Although major vascular reconstructions are rarely needed, surgical teams must anticipate challenging dissections, fragile vessels, and atypical tissue consistency [

2,

9,

31]. This principle is consistent with evidence from adnexal surgery, where accurate intraoperative assessment and recognition of benign adnexal lesions, such as ovarian serous papillary cysts, have been shown to reduce unnecessary radical interventions and perioperative morbidity, while preserving reproductive potential in appropriate patients [

32].

Multiple studies show that irradiated patients have higher rates of perioperative complications, largely related to tissue friability, impaired wound healing, and hemorrhagic risk rather than overt macrovascular events. This is consistent with our finding of a higher complication rate in cervical cancer patients, despite similar rates of major vascular injury compared to controls [

8,

10,

33,

34].

These findings underscore the critical role of meticulous surgical technique, early recognition of vulnerable vessels, and access to experienced vascular support during pelvic oncologic surgery.

Macrovascular events (e.g., stenosis, occlusion, pseudoaneurysm) typically occur years after radiation, highlighting the importance of long-term vascular surveillance even in asymptomatic patients, maintaining a high index of suspicion during follow-up, and integrating vascular imaging into survivorship care when appropriate [

15,

35].

When vascular complications do occur, the literature supports a preference for endovascular management over open repair in irradiated fields, due to the fragility of the tissues and the higher risk of surgical complications [

15,

36]. This principle can be extrapolated to the pelvis: conservative or endovascular interventions should be considered first-line whenever feasible.

Given the interplay between oncologic treatment, vascular changes, and surgical complexity, optimal patient care necessitates preoperative evaluation with vascular and anesthesia teams, individualized surgical planning based on prior radiation exposure, proactive perioperative hemostatic strategies, and immediate access to interventional radiology for rapid response.

Furthermore, adjuvant systemic therapies such as cisplatin may amplify vascular fragility [

22] cisplatin, supporting the need for integrated oncologic–vascular risk stratification. Individual variability—including baseline cardiovascular comorbidities and possible genetic susceptibility—can modulate the severity of radiation vasculopathy [

20,

37]. Incorporating these factors into clinical decision-making enables the identification of high-risk patients before surgery, the implementation of tailored intraoperative precautions, and the establishment of structured vascular follow-up for early detection of delayed complications.

Irradiated pelvic fields necessitate anticipation of surgical challenges, even in the absence of macrovascular stenosis, as complications often stem from compromised tissue quality rather than overt vascular occlusion. When intervention is required, endovascular strategies should be prioritized, and long-term vascular monitoring is recommended due to the risk of delayed events. Multidisciplinary perioperative planning enhances patient safety, while individualized risk profiling can help optimize surgical and long-term outcomes.

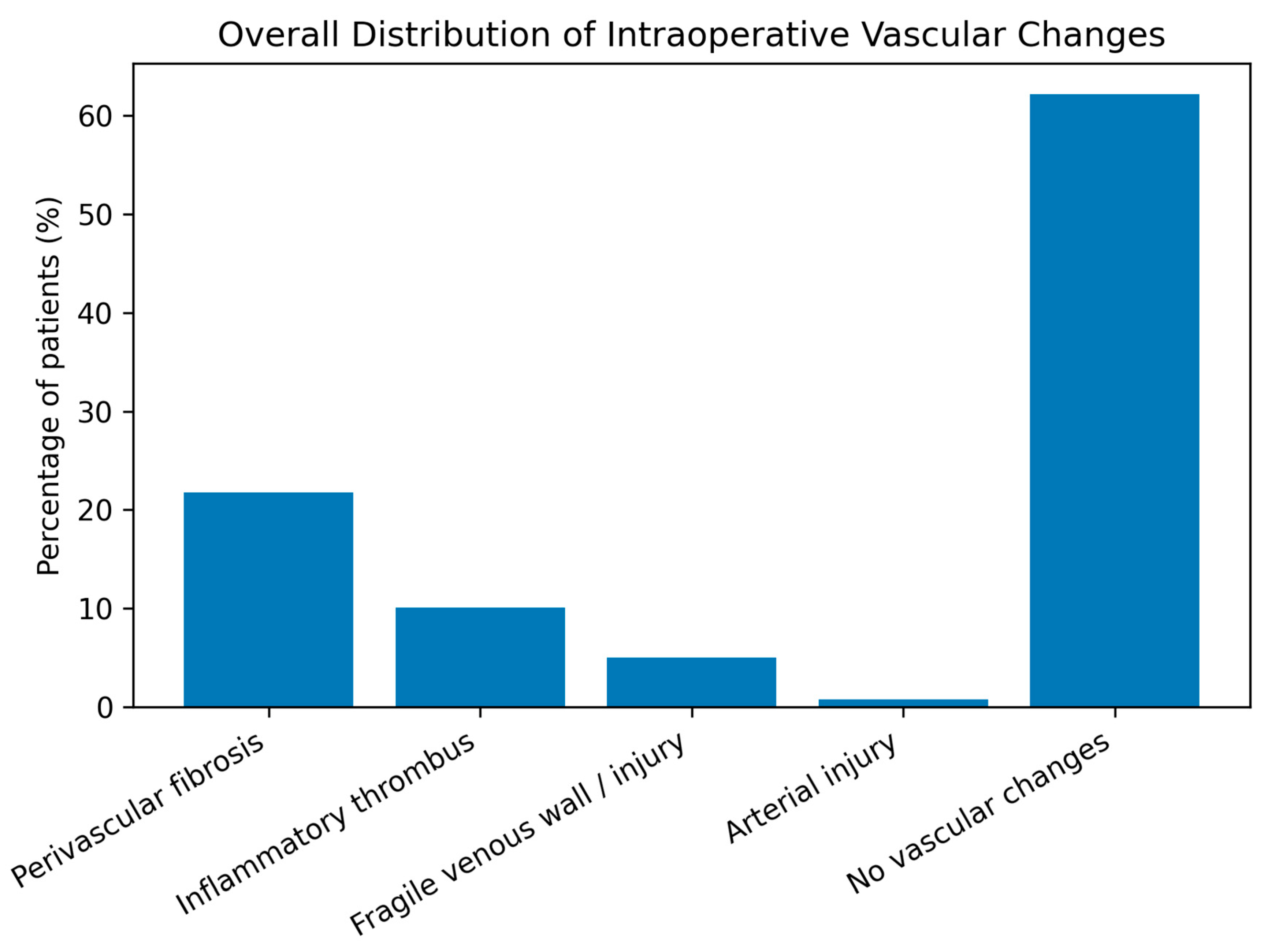

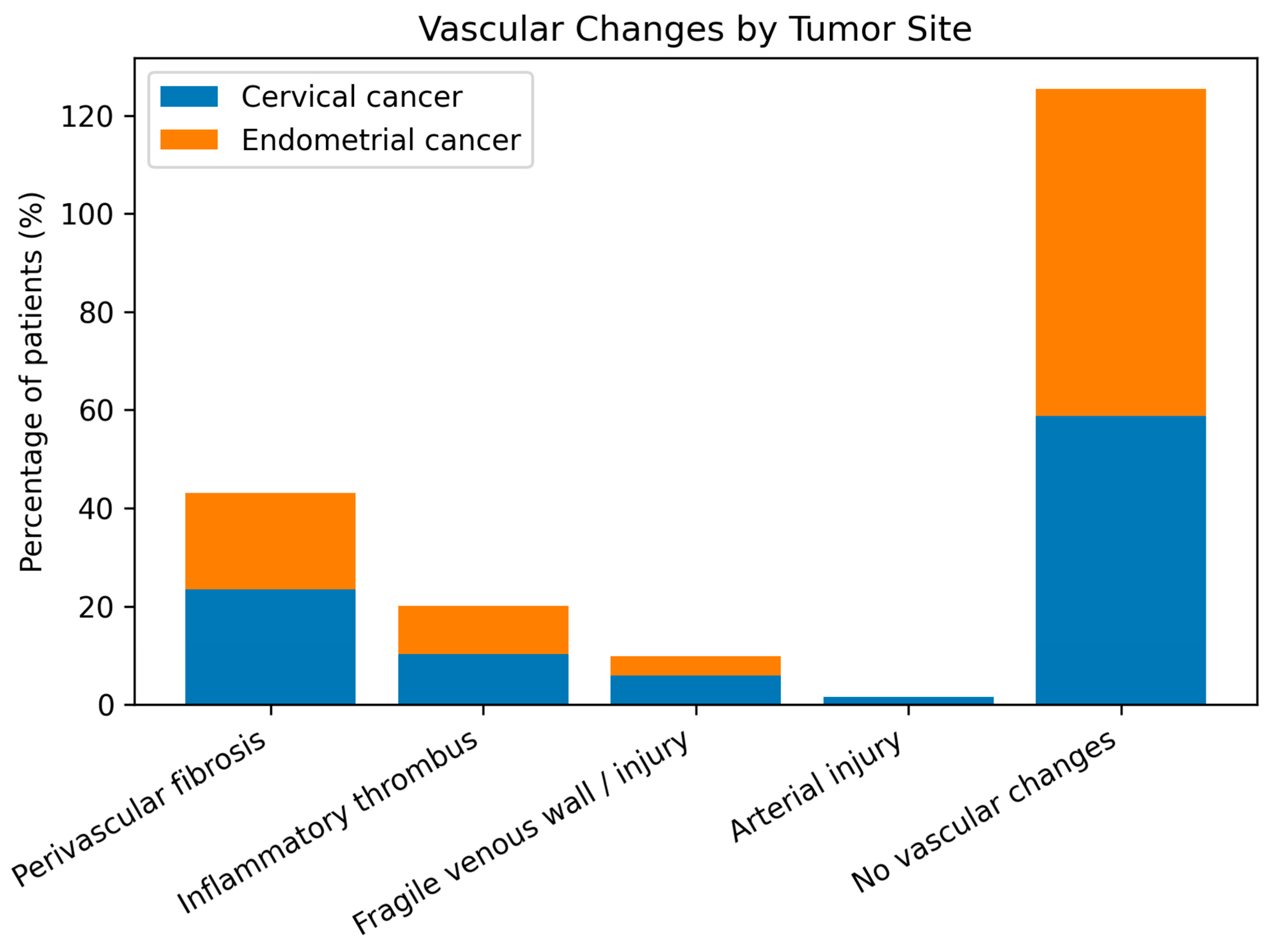

In this cohort of patients with pelvic malignancies treated with radiotherapy, several clinically relevant patterns were observed. Cervical cancer predominated over endometrial cancer (57.1% vs. 42.9%), reflecting the known epidemiologic and virologic profile of the disease, while endometrial cancer patients were significantly older, highlighting distinct risk factors and tumor biology. Intraoperative vascular alterations such as perivascular fibrosis (≈22%) and inflammatory thrombus (≈10%) were common but did not differ significantly between tumor types. Although complex vascular reconstructions were rarely required, the frequent need for conservative management or simple venorrhaphy underscores the technical impact of these changes. Perioperative complications were significantly more frequent in cervical cancer patients (RR = 2.66; p = 0.02), particularly hemorrhage and urinary tract injury, reflecting higher surgical morbidity. Tumor site (cervical) and perivascular fibrosis emerged as borderline predictors of complications (OR ≈ 2.5), suggesting an indirect effect of post-radiation tissue changes on operative risk, while age, inflammatory thrombosis, and macrovascular lesions were not independent predictors, indicating that perioperative morbidity is driven more by tissue quality than by overt vascular pathology.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several important strengths. First, it focuses on a well-defined and clinically relevant cohort of patients undergoing pelvic oncologic surgery after radiotherapy, reflecting real-world surgical practice in a tertiary cancer center. Second, the integration of clinical data and detailed intraoperative assessment provides a comprehensive characterization of radiation-induced vascular and perivascular changes, helping to bridge the gap between known pathophysiological mechanisms and surgical outcomes. Third, the direct comparison between cervical and endometrial cancer patients offers valuable insights into tumor-specific perioperative risk profiles, which have been insufficiently addressed in previous literature. Finally, the standardized surgical approach and detailed intraoperative vascular documentation enhance the internal validity and reproducibility of the findings.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective and single-center design may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the results. The absence of detailed data on comorbidities, lifestyle factors, and functional status limited a more granular patient-level risk stratification. The sample size, while representative for a specialized surgical cohort, may not provide adequate statistical power to detect subtle differences in rare vascular events. In addition, the perioperative observation window was short, precluding conclusions regarding long-term vascular sequelae, which are known to manifest years after radiotherapy. Vascular alterations were assessed primarily intraoperatively, without systematic pre- and postoperative vascular imaging, which may have underestimated subclinical or progressive changes. Moreover, the absence of detailed dosimetric and dose–volume data limits the ability to explore potential dose–response relationships.

Despite these limitations, the present study provides clinically meaningful and original evidence on the vascular impact of pelvic radiotherapy. Its findings support more refined surgical planning, risk stratification, and multidisciplinary perioperative management in patients with gynecologic malignancies previously treated with radiotherapy.