Clinical and Etiopathological Perspective of Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity and an Example of a Desensitization Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Purpose and Method of the Review

3. Vitamin B1 (Thiamine)–History of Discovery and Basic Information

3.1. History of Discovery of Vitamin B1

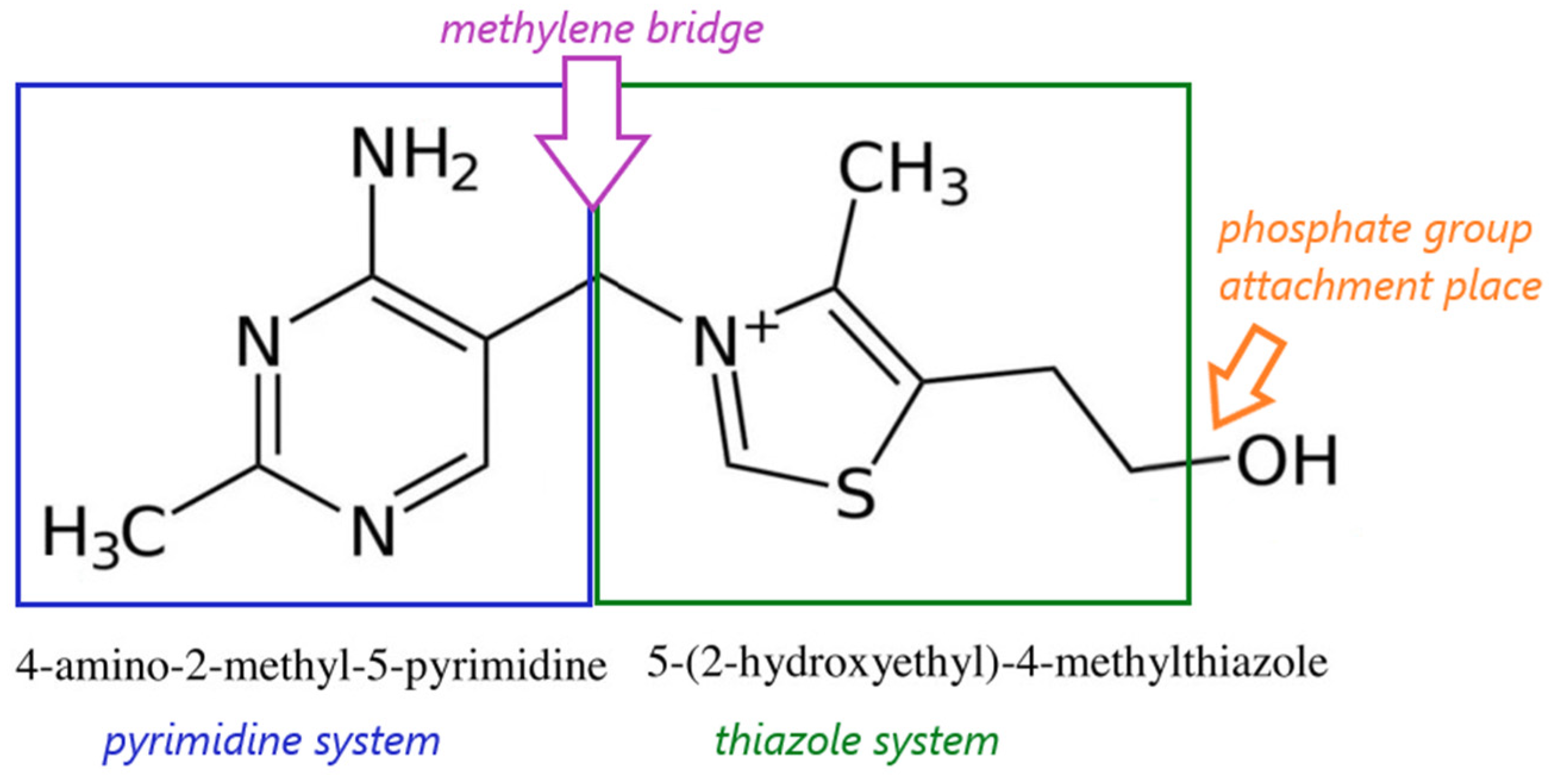

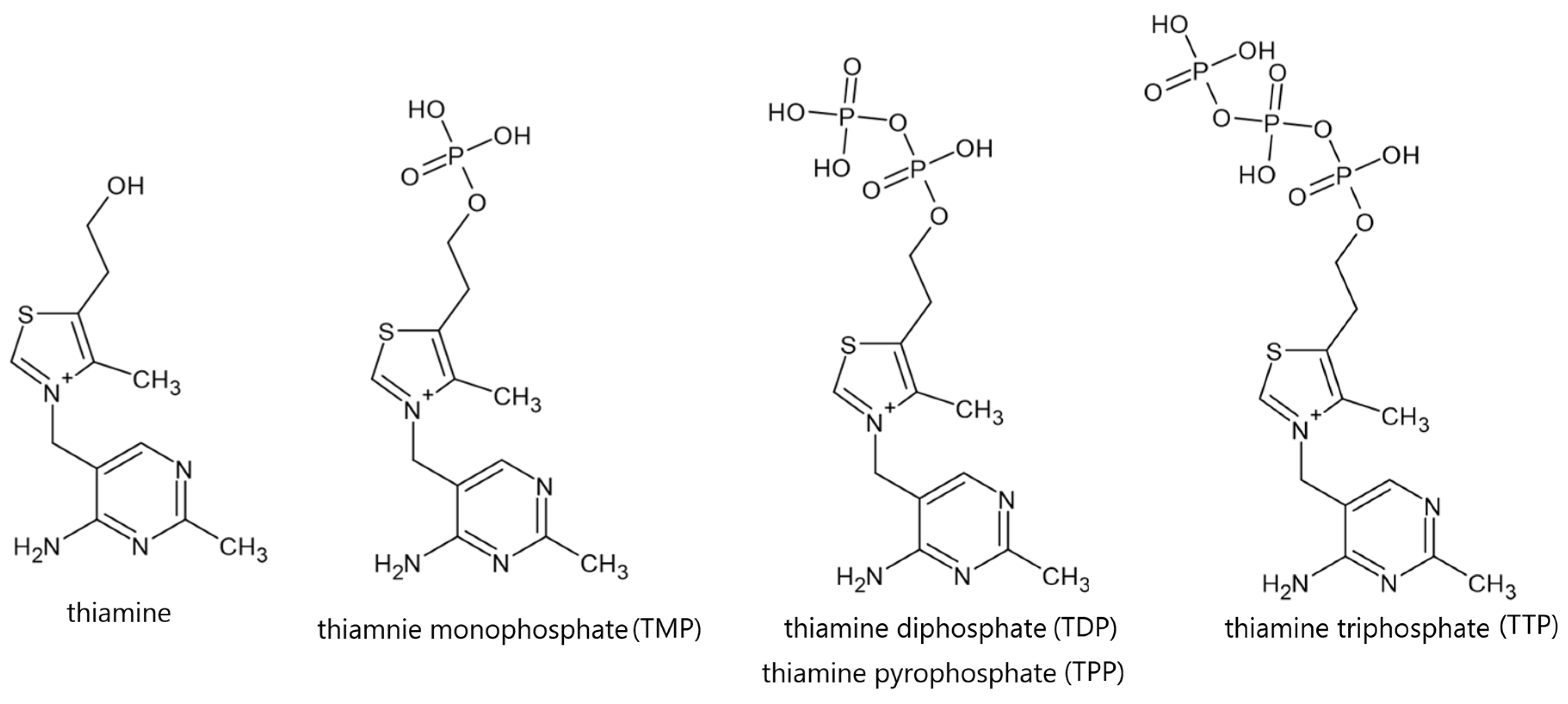

3.2. Physical and Chemical Properties, Natural Sources and Metabolism of Vitamin B1

4. Vitamin B1 Deficiency—Causes and Clinical Effects

4.1. Beri-Beri Disease

4.2. Wernicke–Korsakoff Syndrome

4.3. Vitamin B1 Supplementation

5. Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity

5.1. Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity in Clinical Cases

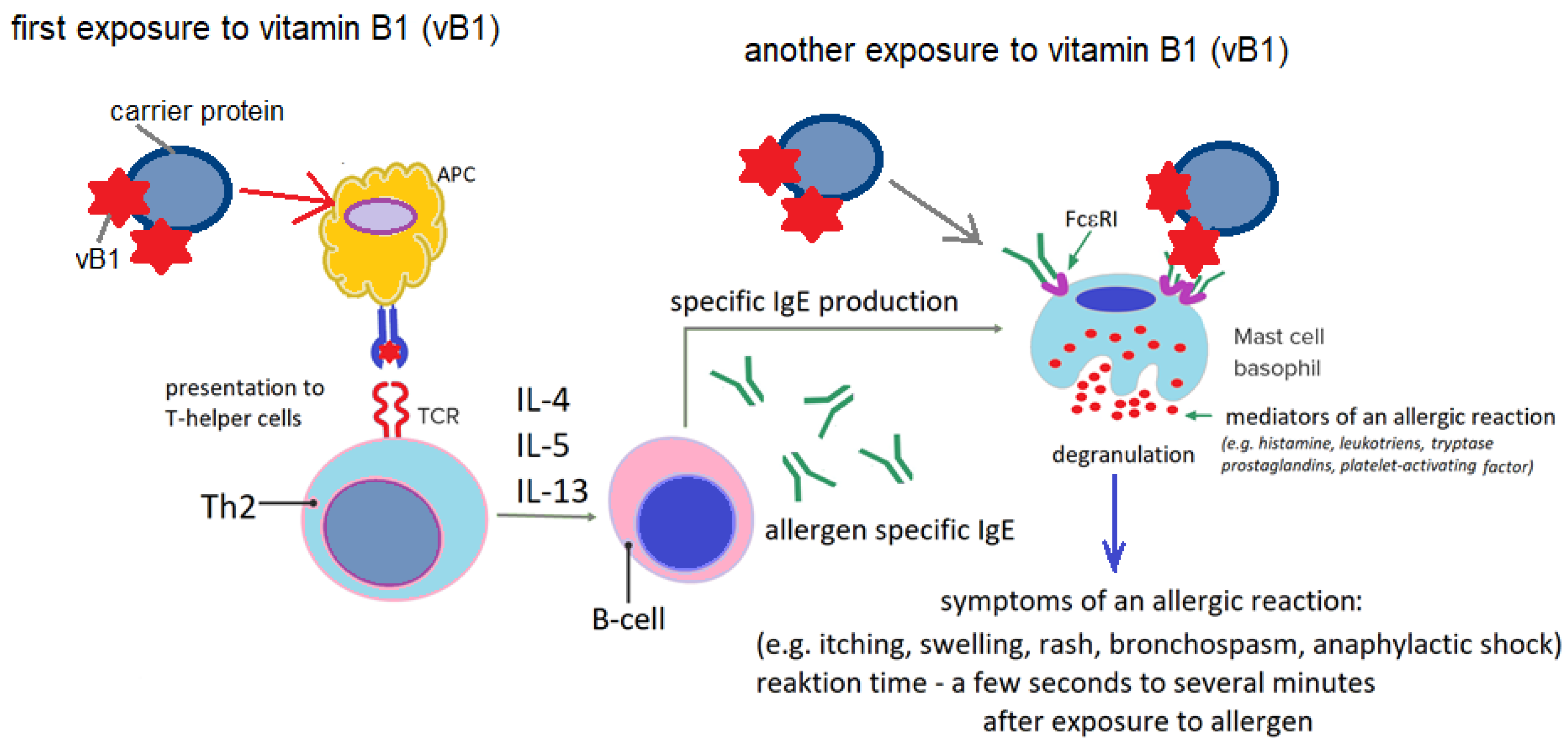

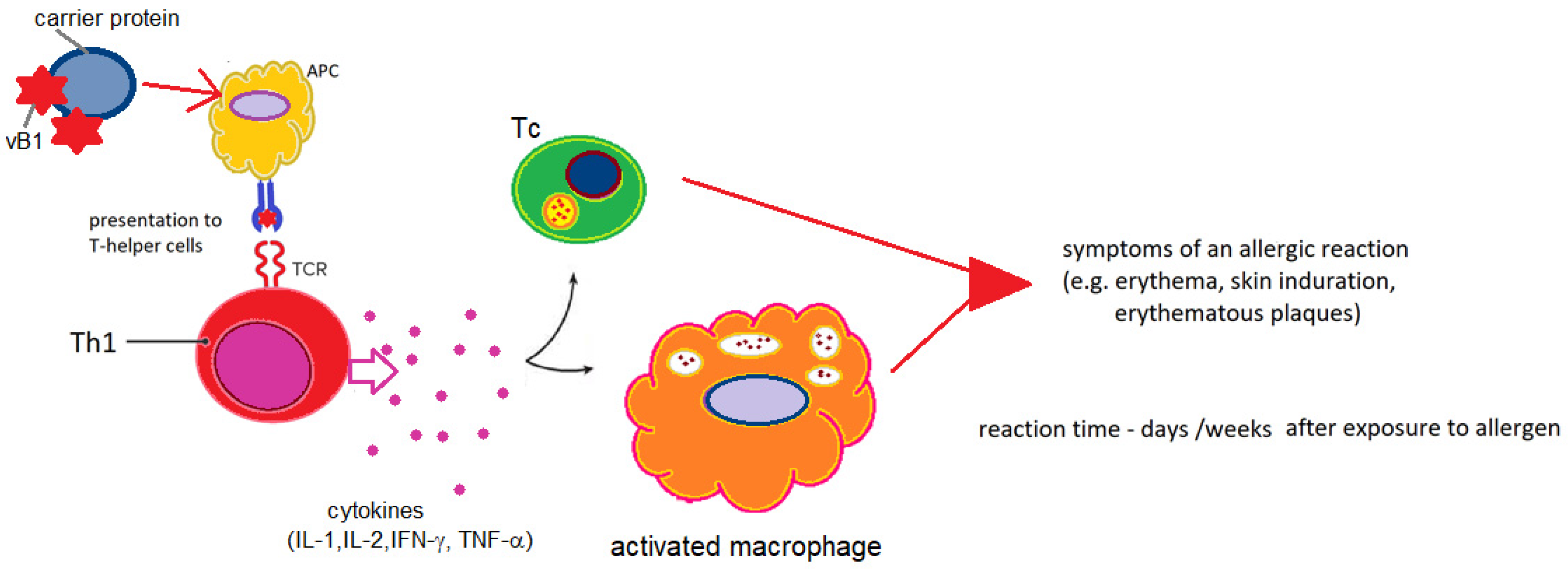

5.2. Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity-Probable Etiopathogenetic Mechanisms

5.3. Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity-Diagnostic Possibilities

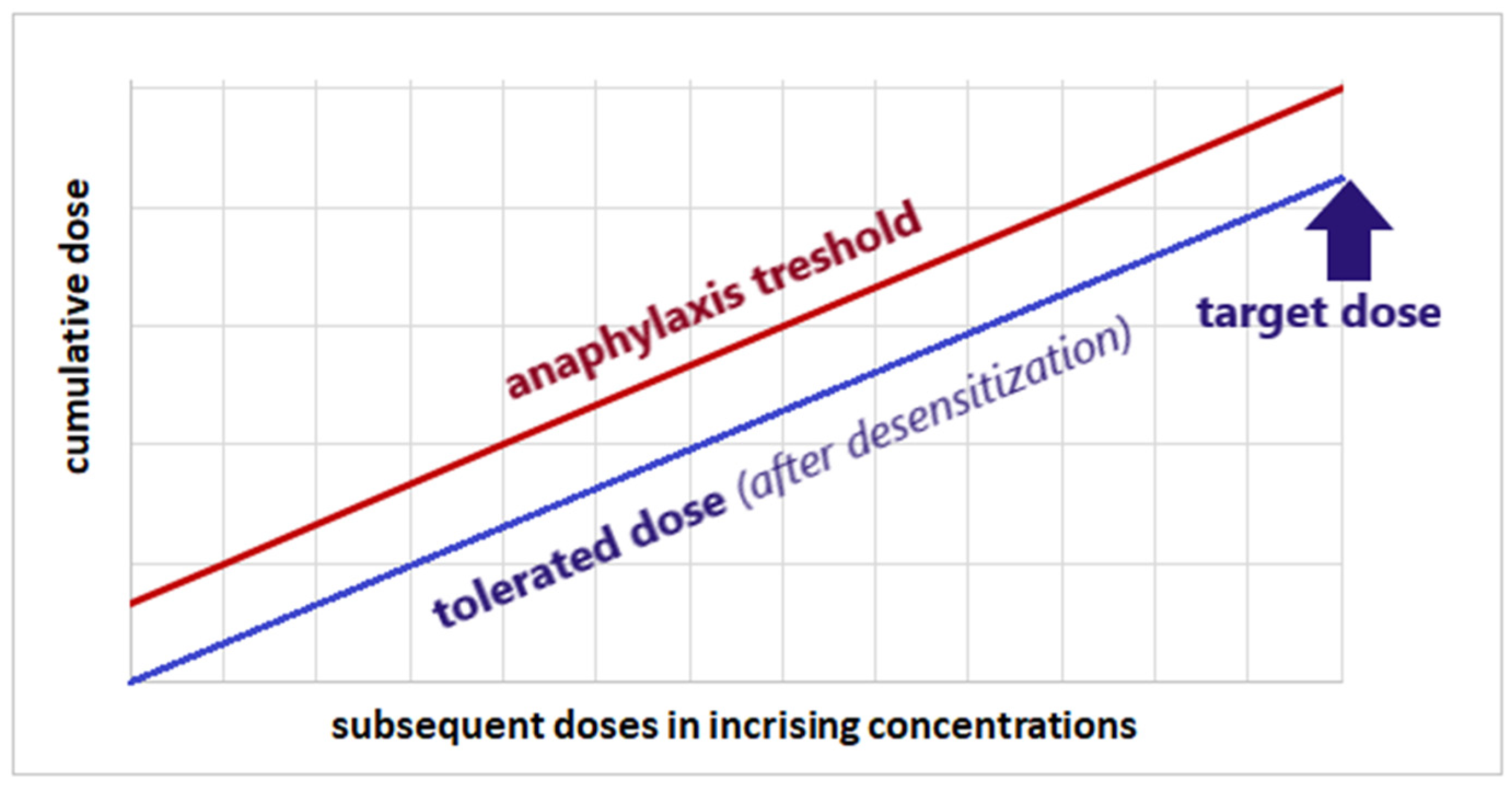

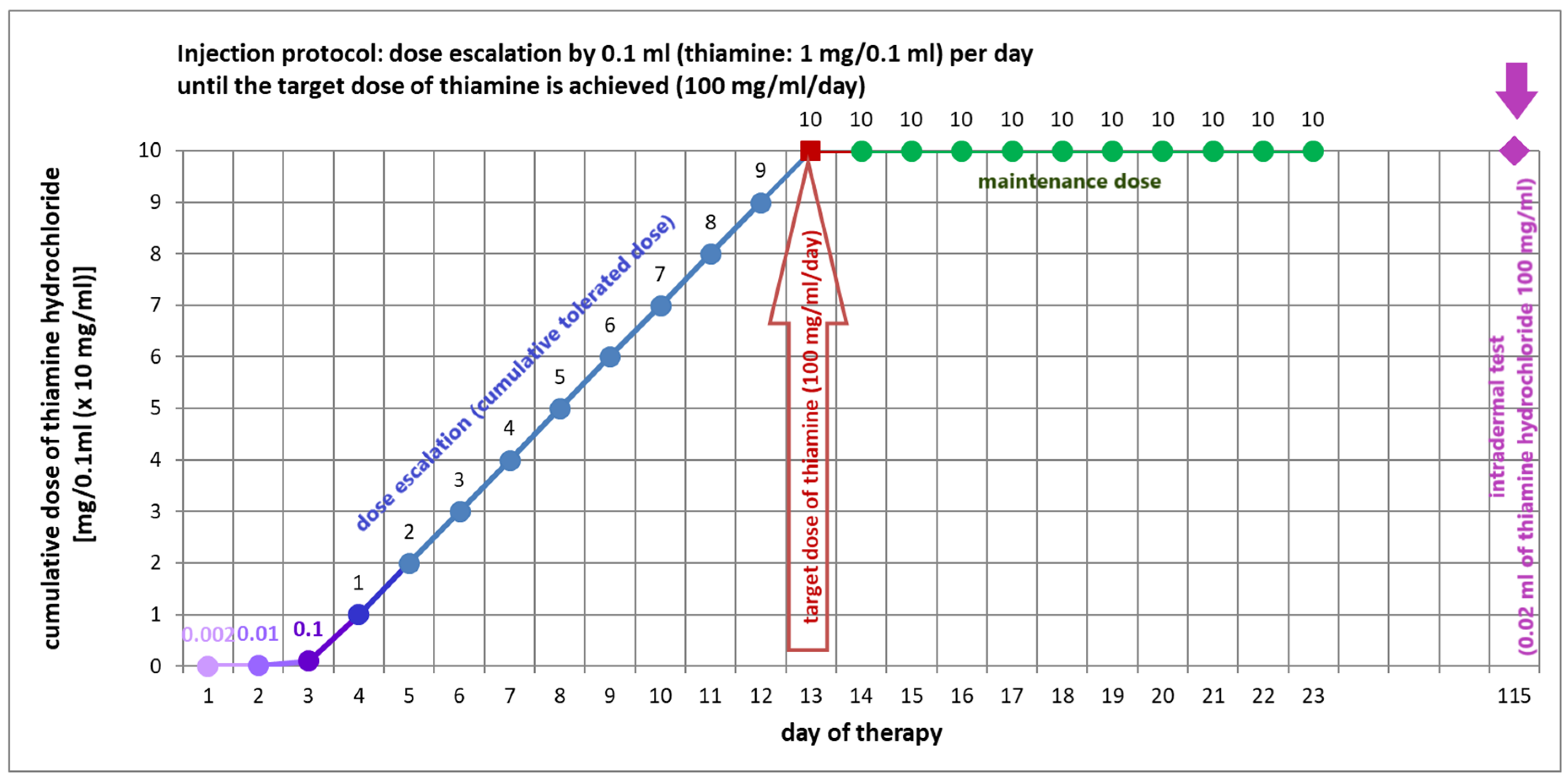

5.4. Vitamin B1 Desensitization as a Therapeutic Option for Thiamine Hypersensitivity

6. Summary and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akram, M.; Minir, N.; Daniyal, M.; Egbuna, C.; Găman, M.A.; Onyekere, P.F.; Olatunde, A. Vitamins and Minerals: Types, Sources and their Functions. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals; Egbuna, C., Dable Tupas, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sight and Life Press. c/o Sight and Life/DSM Nutritional Products Ltd. Vitamins and Minerals: A Brief Guide. Available online: https://cms.sightandlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/SAL_MVLex_web.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Sinclair, J.; Wilson, A. Vitamins and Minerals. DR. GUIDE BOOK SERIES. 2015. Mediscript Communications Inc. Canada. Available online: https://mediscript.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Vitamins-and-Minerals_Ebook-SAMPLE.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Chawla, J.; Kvarnberg, D. Hydrosoluble vitamins. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014, 120, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykstad, J.; Sharma, S. Biochemistry, Water Soluble Vitamins. [Updated 6 March 2023]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538510/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Steinberg, F.M.; Rucker, R.B.; Ye, L.; Eitenmiller, R. The Water-Soluble Vitamins. In Handbook of Food Science, Technology, and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, C.; Calogiuri, G.; Nettis, E.; De Marco, A.; Stingeni, L.; Hansel, K.; Di Bona, D.; Carlucci, P.; Romita, P.; Barbaud, A. Allergic contact dermatitis from vitamins: A systematic review. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaman, M.; Çatak, J.; Uğur, H.; Gürbüz, M.; Belli, I.; Tanyildiz, S.N.; Yildirim, H.; Cengïz, S.; Yavuz, B.; Kişmiroğlu, C.; et al. The bioaccessibility of water-soluble vitamins: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, H.M. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins in health and disease. Biochem. J. 2011, 437, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubša, M.; Siatka, T.; Nejmanová, I.; Vopršalová, M.; Kujovská Krčmová, L.; Matoušová, K.; Javorská, L.; Macáková, K.; Mercolini, L.; Remião, F.; et al. Biological Properties of Vitamins of the B-Complex, Part 1: Vitamins B1, B2, B3, and B5. Nutrients 2022, 14, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Siatka, T.; Vopršalová, M.; Moravcová, M.; Pourová, J.; Přívratská, N.; Krčmová, L.K.; Javorská, L.; Mladěnka, P. Biological properties of vitamins of the B-complex, part 2—Vitamins B6 and B7 (biotin, vitamin H). Nutr. Res. Rev. 2025, 38, 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.; Jaqua, E.; Nguyen, V.; Clay, J. B Vitamins: Functions and Uses in Medicine. Perm. J. 2022, 26, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram-Weston, Z.; Knight, J.; Andrade-Sienz, M. Vitamin B complex: B group vitamins and their role in the body. Nurs. Times 2024, 120, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Napiórkowska, E. Thiamine (vitamin b1): Overview of history of discovery, mechanism of action, role and deficiency. Prospect. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 21, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, A.; Tagarelli, G.; Lagonia, P.; Tagarelli, A.; Quattrone, A. Casimir Funk: His discovery of the vitamins and their deficiency disorders. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 57, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, K.J. The discovery of thiamin. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 61, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoef, J.; Snippe, H.; Nottet, H.S. Christiaan Eijkman. First bacteriologist at Utrecht University, Nobel laureate for his work on vitamins. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1999, 75, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, C. The etiology of the deficiency diseases. Beri-beri, polyneuritis in birds, epidemic dropsy, scurvy, experimental scurvy in animals, infantile scurvy, ship beri-beri, pellagra. J. State Med. 1912, 20, 341–368. [Google Scholar]

- Griminger, P. Casimir Funk: A Biographical Sketch (1884–1967). J. Nutr. 1972, 102, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J.; Halczuk, K.; Karwowski, B.T. Thiamine (Vitamin B1)—An Essential Health Regulator. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Dragan, G.; Majsterek, I. The importance of thiamine (vitamin B1) in humans. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43, BSR20230374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapala-Kozik, M. Vitamin B1 (Thiamine): A Cofactor for Enzymes Involved in the Main Metabolic Pathways and an Environmental Stress Protectant. Adv. Bot. Res. 2011, 58, 37–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattal-Valevski, A. Thiamine (Vitamin B1). J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 16, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylicki, A.; Siemieniuk, M. Thiamine and its derivatives in the regulation of cell metabolism. Postępy Hig. Med. Doświadczalnej 2011, 65, 447–469. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, D. A review of the biochemistry, metabolism and clinical benefits of thiamin(e) and its derivatives. Evid.-Based. Complement. Altern. Med. 2006, 3, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaluri, P.; Castillo, A.; Edriss, H.; Nugent, K. Thiamine Deficiency: An Important Consideration in Critically Ill Patients. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 356, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettendorff, L. Update on Thiamine Triphosphorylated Derivatives and Metabolizing Enzymatic Complexes. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacei, F.; Tesone, A.; Laudi, N.; Laudi, E.; Cretti, A.; Pnini, S.; Varesco, F.; Colombo, C. The Relevance of Thiamine Evaluation in a Practical Setting. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryszczyńska, A. B vitamins—Natural sources, role in the body, effects of vitamin deficiency. Post. Fitoter. 2009, 4, 229–238. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Małecka, S.A.; Poprawski, K.; Bilski, B. Prophylactic and therapeutic application of thiamine (vitamin B1)—A new point of view. Wiad. Lek. 2006, 59, 383–387. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.L. Thiamin in clinical practice. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2015, 39, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperi, V.; Sibilano, M.; Savini, I.; Catani, M.V. Niacin in the central nervous system: An update of biological aspects and clinical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, K.; Manzanares, W.; Joseph, K. Thiamine in nutrition therapy. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2012, 27, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiezagha, K.; Ali, S.; Freeman, C.; Barker, N.C.; Jabeen, S.; Maitra, S.; Olagbemiro, Y.; Richie, W.; Bailey, R.K. Thiamine deficiency and delirium. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 10, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, K.D.; Gupta, M. Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) Deficiency. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US). Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline. In Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.G.; Cunha, L.N.P.; Paiva, S.A.R.; Azevedo, P.S.; Zornoff, L.A.M.; Polegato, B.F.; Costa, N.A.; Minicucci, M.F. An Overview of Beriberi. Med. Princ. Pract. 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourassa, M.W.; Bergeron, G.; Brown, K.H. A fresh look at thiamine deficiency-new analyses by the global thiamine alliance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1498, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.J.; Johnson, C.R.; Koshy, R.; Hess, S.Y.; Qureshi, U.A.; Mynak, M.L.; Fischer, P.R. Thiamine deficiency disorders: A clinical perspective. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1498, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouraghda, M.A.; Bouzid, M.A.; Ais, I.; Zighoud, S.; Elbesseghi, H.; Chettibi, M. Beri-beri Disease: Forgotten but Not Gone! Sch. J. Med. Case Rep. 2023, 11, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shible, A.A.; Ramadurai, D.; Gergen, D.; Reynolds, P.M. Dry Beri-beri Due to Thiamine Deficiency Associated with Peripheral Neuropathy and Wernicke’s Encephalopathy Mimicking Guillain-Barré syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Case Rep. 2019, 20, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhouri, S.; Kuhn, J.; Newton, E.J. Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome. [Updated 26 June 2023]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430729/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Arts, N.J.; Walvoort, S.J.; Kessels, R.P. Korsakoff’s syndrome: A critical review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 2875–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.; Dixon, G.; Sheedy, D.; Garrick, T. Neuropathological alterations in alcoholic brains. Studies arising from the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Boil. Psychiatry 2003, 27, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnan, M. Protocols of Thiamine Supplementation: Clinically Driven Rationality vs. Biological Commonsense. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.F. Use of Thiamine Supplementation in Pregnant Women Diagnosed With Hyperemesis Gravidarum and Wernicke Encephalopathy. Nurs. Women’s Health 2024, 28, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.M.; Shenkin, A.; Dizdar, O.S.; Amrein, K.; Augsburger, M.; Biesalski, H.K.; Bischoff, S.C.; Casaer, M.P.; Gundogan, K.; Lepp, H.L.; et al. ESPEN practical short micronutrient guideline. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 825–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.; Joyal, K.; Lee, S.; Corrado, M.; Marquis, K.; Anger, K.; Szumita, P. Safety of intravenous push thiamine administration at a tertiary academic medical center. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2003, 60, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhaeefi, M.; McLaughlin, K.; Goodberlet, M.; Szumita, P. Evaluation of the safety of 500 mg intravenous push thiamine at a tertiary academic medical center. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105, 368504221096539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjugum, S.L.; Hedrick, T.L.; Jean, S.J.; Heeney, S.A.; Rohde, K.A.; Campbell-Bright, S.L. Evaluation of the Safety of Intravenous Thiamine Administration in a Large Academic Medical Center. J. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 34, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laws, C.L. Sensitization to thiamine hydrochloride. JAMA 1941, 117, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrani, M.M. Vitamin B1 hypersensitivity with desensitization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1944, 15, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, V.C.; Englehardt, H.T. Sensitivity to thiamine hydrochloride, review of the literature and report of a case. Med. Bull. (N. Y.) 1946, 6, 364–366. [Google Scholar]

- Reingold, I.M.; Webb, F.R. Sudden death following intravenous injection of thiamine hydrochloride. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1946, 130, 491. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero, W.; Gwinner, M.W. Sensitivity to thiamine hydrochloride; report of a case. Ann. Allergy 1947, 5, 349–352. [Google Scholar]

- Armanino, L.P.; Scott, W.S., Jr. Anaphylactic shock following intravenous administration of thiamine chloride; report of a case. Calif. Med. 1950, 72, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Combes, F.C.; Groopman, J. Contact dermatitis due to thiamine. Arch. Dermatol. Syphilol. 1950, 61, 858–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaros, S.H.; Wnuck, A.L.; Debber, E.J. Thiamine intolerance. Ann. Allergy 1952, 10, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Lawick van Pabst, H.M. Hazards of vitamin B1 injections. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 1952, 96, 1183–1184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tetreault, A.F.; Beck, I.A. Anaphylactic shock following intramuscular thiamine chloride. Ann. Intern. Med. 1956, 45, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjorth, N. Contact dermatitis from vitamin B1 (thiamine); relapse after ingestion of thiamine, cross-sensitization to cocarboxylase. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1958, 30, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaikov, S.; Gumeniuk, G.; Veselovsky, L. The problem of hypersensitivity to vitamin preparations. Infus. Chemother. 2021, 4, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.S.; Kuo, M.L.; Huang, J.L. Anaphylaxis to riboflavin (vitamin B2). Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001, 87, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrenn, K.D.; Murphy, F.; Slovis, C.M. A toxicity study of parenteral thiamine hydrochloride. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1989, 18, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratani, M.; Hiraga, T.; Terasawa, H.; Hosokawa, O.; Mitsuto, O. A case of anaphylactic shock due to vitamin B1 derivative (thiamine monophosphate disulfide). Arerugi No Rinsho (Allergy Pract.) 1992, 12, 1036–1039. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, M.; Barceló, M.; Muñoz, C.; Torrecillas, M.; Blanca, M. Anaphylaxis to thiamine (vitamin B1). Allergy 1997, 52, 958–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, S.; Shetty, S.; Soni, A.; Kumar, S. Anaphylaxis from intravenous thiamine—Long forgotten? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2000, 18, 642–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Kambara, T.; Fujimura, N.; Nakamura, K.; Hirokado, M.; Matsukura, S.; Ikezawa, J. A case of anaphylactic shock due to thiamine monophosphate disulfide, a derivative of vitamin B1. J. Environ. Dermatol. Cutan. Allergol. 2012, 6, 368–372. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Juel, J.; Pareek, M.; Langfrits, C.S.; Jensen, S.E. Anaphylactic shock and cardiac arrest caused by thiamine infusion. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013009648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, A.; Takahagi, S.; Kinoshita, H.; Nakamura, R.; Ishii, K.; Hide, M. Anaphylaxis due to thiamine disulfide phosphate, a derivative of vitamin B1; a case report and literature review. Allergol. Int. 2022, 71, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, J.; Adachi, A.; Nagahama, M.; Yamada, H.; Masuda, Y.; Kitamura, H. A case of anaphylaxis induced by vitamin B1 derivative infusion formulation for intravenous injection. Arerugi 2023, 72, 479–484. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Haecke, P.; Ramaekers, D.; Vanderwegen, L.; Boonen, S. Thiamine-induced anaphylactic shock. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1995, 13, 371–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurich, S.; Simon, J.C.; Treudler, R. A Case of Anaphylaxis to Intramuscular but Not to Oral Application of Thiamine (Vitamin B1). Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 17, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Sánchez-Domínguez, M.; Noguerado-Mellado, B.; Rojas-Pérez-Ezquerra, P. Urticaria by thiamine (vitamin B1). Allergol. Int. 2018, 67, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proebstle, T.M.; Gall, H.; Jugert, F.K.; Merk, H.F.; Sterry, W. Specific IgE and IgG serum antibodies to thiamine associated with anaphylactic reaction. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1995, 95, 1059–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Casey, P. Angioneurotic oedema secondary to oral thiamine. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013200558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruti, N.; Bernedo, N.; Audicana, M.T.; Villarreal, O.; Uriel, O.; Muñoz, D. Systemic allergic dermatitis caused by thiamine after iontophoresis. Contact Dermat. 2013, 69, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drought, V.J.; Francis, H.C.; Niven, R.M.; Burge, P.S. Occupational asthma induced by thiamine in a vitamin supplement for breakfast cereals. Allergy 2005, 60, 1213–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, I.A.; Jepsen, R.J.; Thulin, H. Allergic contact dermatitis from thiamine. Contact Dermat. 1989, 20, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindi, G.; Ricci, V.; Gastaldi, G.; Patrini, C. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase can transphosphorylate thiamin to thiamin monophosphate during intestinal transport in the rat. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 1995, 103, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, R.; Puy, R.; Czarny, D. Thiamine anaphylaxis. Med. J. Aust. 1993, 159, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, H.J.; Santos, A.F.; Mayorga, C.; Nopp, A.; Eberlein, B.; Ferrer, M.; Rouzaire, P.; Ebo, D.G.; Sabato, V.; Sanz, M.L.; et al. The clinical utility of basophil activation testing in diagnosis and monitoring of allergic disease. Allergy 2015, 70, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga, C.; Çelik, G.E.; Pascal, M.; Hoffmann, H.J.; Eberlein, B.; Torres, M.J.; Brockow, K.; Garvey, L.H.; Barbaud, A.; Madrigal-Burgaleta, R.; et al. Flow-based basophil activation test in immediate drug hypersensitivity. An EAACI task force position paper. Allergy 2024, 79, 580–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.; Nanjappa, N.C.; Perkins, G.B.; Di Lernia, R.; Thiruvenkatarajan, V.; Hissaria, P. Basophil activation test in the diagnostic workup of perioperative anaphylaxis due to neuromuscular blocking agents: A case series and implications for practice. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2024, 52, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.; Mendes, A.; Neves, E.; Falcão, H.; Gomes, E. Folic acid allergy and the role of the basophil activation test. Rev. Port. Imunoalergologia 2024, 32, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Hidalgo, A.; Pérez-Montoya, M.; Cañas, J.A.; Valverde-Monge, M.; Rodrigo-Muñoz, J.M.; Gil-Martínez, M.; Gómez-López, A.; Otal-Buesa, M.; Del Pozo Abejón, V.; Fernández-Nieto, M. Basophil Activation Test: An Additional Diagnostic Tool in Vitamin B12 Allergy. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2025, 35, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Desensitization for drug allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 6, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Rapid desensitization for hypersensitivity reactions to medications. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2009, 29, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Sancho, M.; Breslow, R.; Sloane, D.; Castells, M. Desensitization for hypersensitivity reactions to medications. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 2012, 97, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vultaggio, A.; Matucci, A.; Nencini, F.; Bormioli, S.; Vivarelli, E.; Maggi, E. Mechanisms of Drug Desensitization: Not Only Mast Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 23, 590991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.C.; Castells, M.C. The Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How of Drug Desensitization. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2022, 42, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamichi-Santos, R.; Castells, M. Diagnoses and Management of Drug Hypersensitivity and Anaphylaxis in Cancer and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Reactions to Taxanes and Monoclonal Antibodies. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 54, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Y.; Seo, J.; Kang, H.R. Desensitization for the prevention of drug hypersensitivity reactions. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Products | B1 mg/100 g | Animal Products | B1 mg/100 g | Other Products | B1 mg/100 g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oranges | 0.1 | Pork tenderloin | 1.1 | Brewer’s yeast (dried) | 15–20 |

| Pineapple | 0.08 | Pork | 0.54 | Baker’s yeast (dried) | 2.7–6.6 |

| Banana | 0.05 | Pork liver | 0.43 | ||

| Apple | 0.04–0.12 | Beef | 0.7 | ||

| Blueberries | 0.03 | Beef liver | 0.3 | ||

| Strawberries | 0.03 | Veal (heart) | 0.6 | ||

| Peaches | 0.03 | Veal | 0.09 | ||

| Whole wheat flour | 0.55 | Poultry (duck/goose) | 0.1 | ||

| Whole rye flour | 0.3 | Salmon | 0.17 | ||

| Brown rice | 0.29 | Trout | 0.09 | ||

| Soybeans | 0.85 | Eggs | 0.12 | ||

| White beans | 0.6 | Cheese | 0.02–0.06 | ||

| Green peas | 0.32 | Cow’s milk | 0.04 | ||

| Cauliflower | 0.11 | Breast milk | 0.01 | ||

| Brussels sprouts | 0.1 | ||||

| Cabbage | 0.05 | ||||

| Potatoes | 0.07 | ||||

| Carrots | 0.06 | ||||

| Tomatoes | 0.06 | ||||

| Oranges | 0.1 |

| Author(s) (Year of Publication) [Reference Number] | Patient: Gender/Age | Clinical Symptoms | Product/Route of Administration | Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous injection | ||||

| Reingold, I.M.; Web, F.R./1946 [54] | M/- | Fatal anaphylaxis | Thiamine hydrochloride/intravenously | Not done |

| Armanino, L.P.; Scott, W.S. (1950) [56] | M/39 y. | Wheezed and noted some pruritus shortly after the second injection Anaphylactic shock two or three minutes after another injection (4 months after the first episode) | Thiamine hydrochloride (10 mg)/intravenously | Not done |

| Hiratani, M. et al. (1992) [65] | F/54 y. | Anaphylactic shock | Vitamedin® (a vitamin B complex; includes TDSP, 107.13 mg/vial; pyridoxine hydrochloride, 100 mg/vial; cyanocobalamin, 1 mg/vial; D-mannitol, 400 mg/vial)/intravenously | Intradermal test with TDSP-positive result. Patch test with TDSP with negative result |

| Fernandez, M. et al. (1997) [66] | F/52 y. | Systemic pruritus, generalized erythema, and hypotension (20 min after injection) | Thiamine hydrochloride in a combination drug (vitamins B1 and B12, Xylocaine, and dexamethasone)/intravenously | Intradermal test with single ingredients, with positive result for vitamin B1. Thiamine-specific IgE (ELISA) |

| Johri, S. et al. (2000) [67] | F/51 y. | Deep cyanosis, shallow, labored breathing, rhythm and blood pressure disorders (20 min after injection); three-time episode | Thiamine hydrochloride (100 mg)/intravenously | Not done |

| Takahashi, Y. et al. (2012) [68] | M/56 y. | Anaphylactic shock | Nornicicamin® (TDSP, Pyridoxine Hydrochloride, Hydroxocobalamin)/intravenously | Intradermal test with TDSP-positive result Patch test with TDSP-positive result |

| Juel, J. et al. (2013) [69] | M/44 y. | Cardiac arrest due to anaphylactic shock | Thiamine hydrochloride (300 mg)/intravenously | Not done |

| Amano, A. et al. (2022) [70] | M/80 y. | Anaphylaxis (with generalized pruritus, dyspnea, and decreased blood pressure) immediately after injection | Vitamedin® (a vitamin B complex, which includes TDSP, 107.13 mg/vial; pyridoxine hydrochloride, 100 mg/vial; cyanocobalamin, 1 mg/vial; D-mannitol, 400 mg/vial)/intravenously | Skin prick test with Vitamedin® (as is), with positive result (wheal after 15 min and anaphylactic shock after 30 min). Histamine release test with the following:

|

| Kumagai, J. et al. (2023) [71] | F/20 y. | Anaphylactic shock | multivitamin witch TDSP/intravenously | Intradermal test with the following:

|

| Intramuscular injection | ||||

| Mitrani, M.M. (1944) [52] | F/15 y. | Maculo-pruriginous eruption on the face, chest, and on the back (where it was of great intensity and extent) after the first injection (the episode repeated three times after subsequent injections) | Thiamine hydrochloride (50 mg)/intramuscularly | Intradermal tests with thiamine hydrochloride, with positive result |

| Tetreault, A.F.; Beck, A.F. (1956) [60] | M/62 y. | Anaphylactic shock | Thiamine hydrochloride/intramuscularly | Not done |

| Van Haecke, P. et al. (1995) [72] | F/86 y. | Fatal anaphylaxis (2 h after injection) | Thiamine hydrochloride (250 mg)/intramuscularly | Not done |

| Aurich, S. et al. (2018) [73] | F/78 y. | Anaphylaxis after the fourth injection | Thiamine hydrochloride/intramuscularly | Skin prick test with pure commercially available aqueous preparations thiamine hydrochloride, with positive result. Single-blinded, placebo-controlled oral challenge test witch thiamine hydrochloride, and with negative result |

| Rodríguez-Fernández A. et al. (2018) [74] | F/50 y. | Generalized urticaria, edema and facial erythema after 30 min of intramuscular administration | Inzitan® (cyanocobalamin, dexamethasone, pyridoxine, thiamine (50 mg; 25 mg/mL), lidocaine)/intramuscularly | Skin prick test with Inzitan® (as is), with negative result. Intradermal test with Inzitan® ingredients (singly), with thiamine-positive result and rest of ingredients, with negative result |

| Subcutaneous/intradermal injection | ||||

| Laws, C.L. (1941) [51] | F/72 y. | Redness and swelling of the eyes, ears, generalized hives, chest tightness 30 min after injection (during the next treatment series) | Thiamine hydrochloride/subcutaneously | Intradermal tests with the drug used (as is), with positive result |

| Proebstle, T.M. et al. (1995) [75] | M/47 y. | Itching of the hands, trunk and neck 30 min after injection. Anaphylaxis 5 min after the second injection (two weeks later) | Thiamine hydrochloride (in a combined drug)/paraepicondyle injection | Thiamine-specific IgE (ELISA) Thiamine-specific IgG (ELISA) Skin prick tests with thiamine hydrochloride, with positive result |

| Oral administration | ||||

| Osman, M.; Casey, P. (2013) [76] | F/47 y. | Swelling of both legs, slightly painful, feeling of heaviness in the legs (after 7 days of supplementation; after 4 days of discontinuing the supplementation the symptoms disappeared). Symptoms of similar dynamics and nature reappeared during the next thiamine supplementation 18 months later | Thiamine hydrochloride (200 mg/day)/orally | Not done |

| Transdermal administration | ||||

| Combes, F.C.; Groopman, J. (1950) [57] | F/35 y. | Dermatitis of the hands and forearms (area of direct exposure to vitamin B1) | Occupational exposure to liquid vitamin B1 (thiamine hydrochloride) | Patch testing with substances related to occupational exposure, with positive result for vitamin B1 |

| Hjorth, N. (1958) [61] | F/17 y. | Hand dermatitis (after 4 months of exposure to thiamine) resolving due to the lack of exposure and recurring after re-exposure | Occupational exposure to liquid vitamin B1 (thiamine hydrochloride) | Patch tests with substances related to occupational exposure, with positive result for thiamine, cocarboxylase and 2-methyl-6-amino-5-brom-methyl-pyrimidine. Intracutaneous tests with thiamine-positive result |

| Arruti, N. et al. (2013) [77] | F/46 y. | Localized, limited, pruritic, micropapular erythematous rash | Voltaren® (diclofenac) and Inzitan® (lidocaine, dexamethasone, cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) and thiamine (vitamin B1))/topical application by iontophoresis | Patch tests with:

Intradermal tests with the implicated drugs (as is), negative results. Oral challenge test with diclofenac, negative results. Intramuscular challenge test with Inzitan®, positive results (24 h after injection, local reaction in the area of previous transdermal application). All tests repeated with each Inzitan® component-positive reactions after thiamine challenge test |

| Airborne (inhalation) exposure | ||||

| Drought, V.J. et al. (2005) [78] | M/46 y. | Bronchial asthma | Occupational exposure to vitamin aerosol containing thiamin hydrochloride | spirometry, reduction of respiratory function parameters after occupational exposure to thiamine when compared with the test results on days free from exposure |

| M/43 y. | ||||

| Transdermal administration and/or airborne (inhalation) exposure | ||||

| Ingemann, L.A. et al. (1989) [79] | M/54 y. | Recurrent itchy eczema on the forearms, hands and face (after a month of exposure) | Occupational exposure to vitamin B1 (thiamine hydrochloride) dust | Patch tests with thiamine (10%, 5%, 1% aq) and thiothiamine (5%, 1% aq), positive results Patch tests (European standard), negative results |

| M/32 y. | Itchy eczema (localized oozing) on hands and feet that spread to the rest of the body (after one month of exposure) | Occupational exposure to vitamin B1 (thiamine hydrochloride) dust. Long-term oral supplementation with vitamin preparations (with vitamin B1) | Patch test with thiamine hydrochloride (10% aq)-Positive result Patch test (European standard), positive results for a mixture of formaldehyde and fragrances | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lis, K. Clinical and Etiopathological Perspective of Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity and an Example of a Desensitization Protocol. Life 2026, 16, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010050

Lis K. Clinical and Etiopathological Perspective of Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity and an Example of a Desensitization Protocol. Life. 2026; 16(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleLis, Kinga. 2026. "Clinical and Etiopathological Perspective of Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity and an Example of a Desensitization Protocol" Life 16, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010050

APA StyleLis, K. (2026). Clinical and Etiopathological Perspective of Vitamin B1 Hypersensitivity and an Example of a Desensitization Protocol. Life, 16(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010050