Genetic Diversity of Prolamin Loci Related to Grain Quality in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) in Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Weather Conditions of the Growing Seasons

2.3. Biochemical Analysis

2.4. Prolamin Extraction

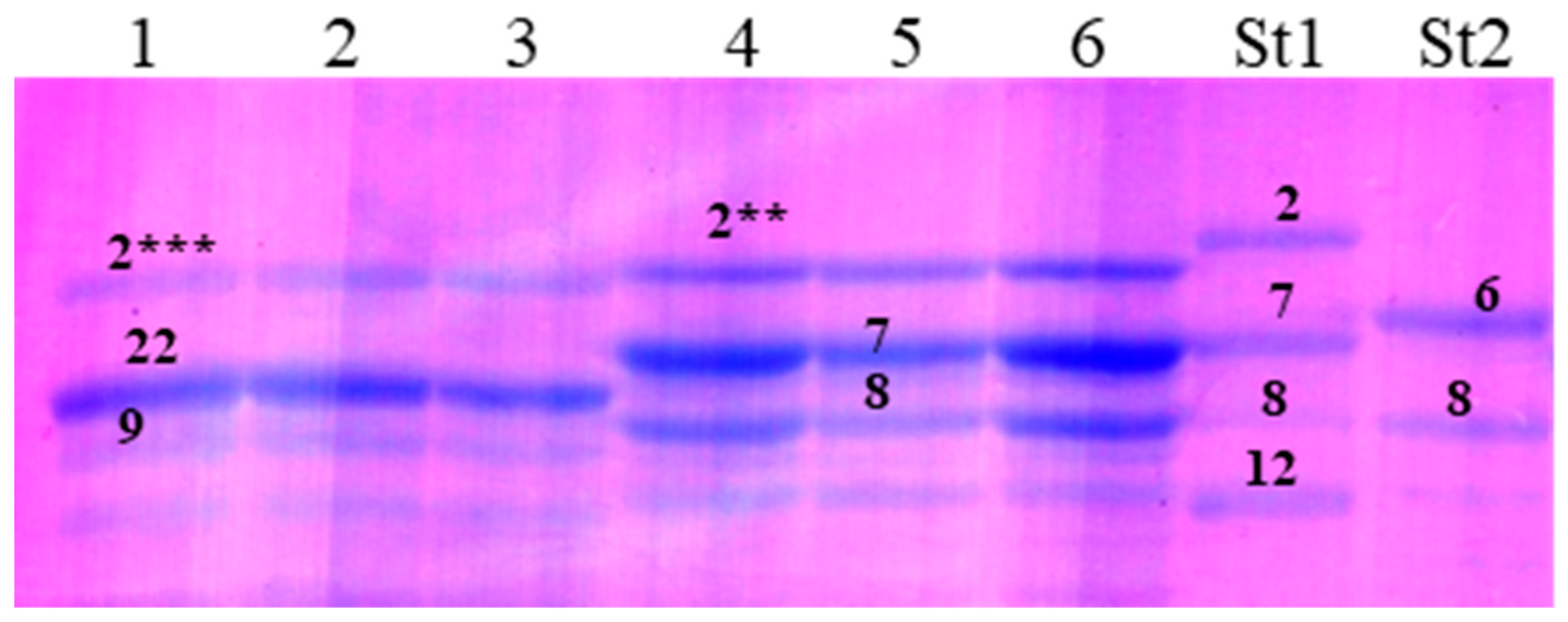

2.5. Gliadin and Glutenin Allele Classification

2.6. Statistical Treatment

3. Results

3.1. Tetraploid Wheat Collection from Kazakhstan

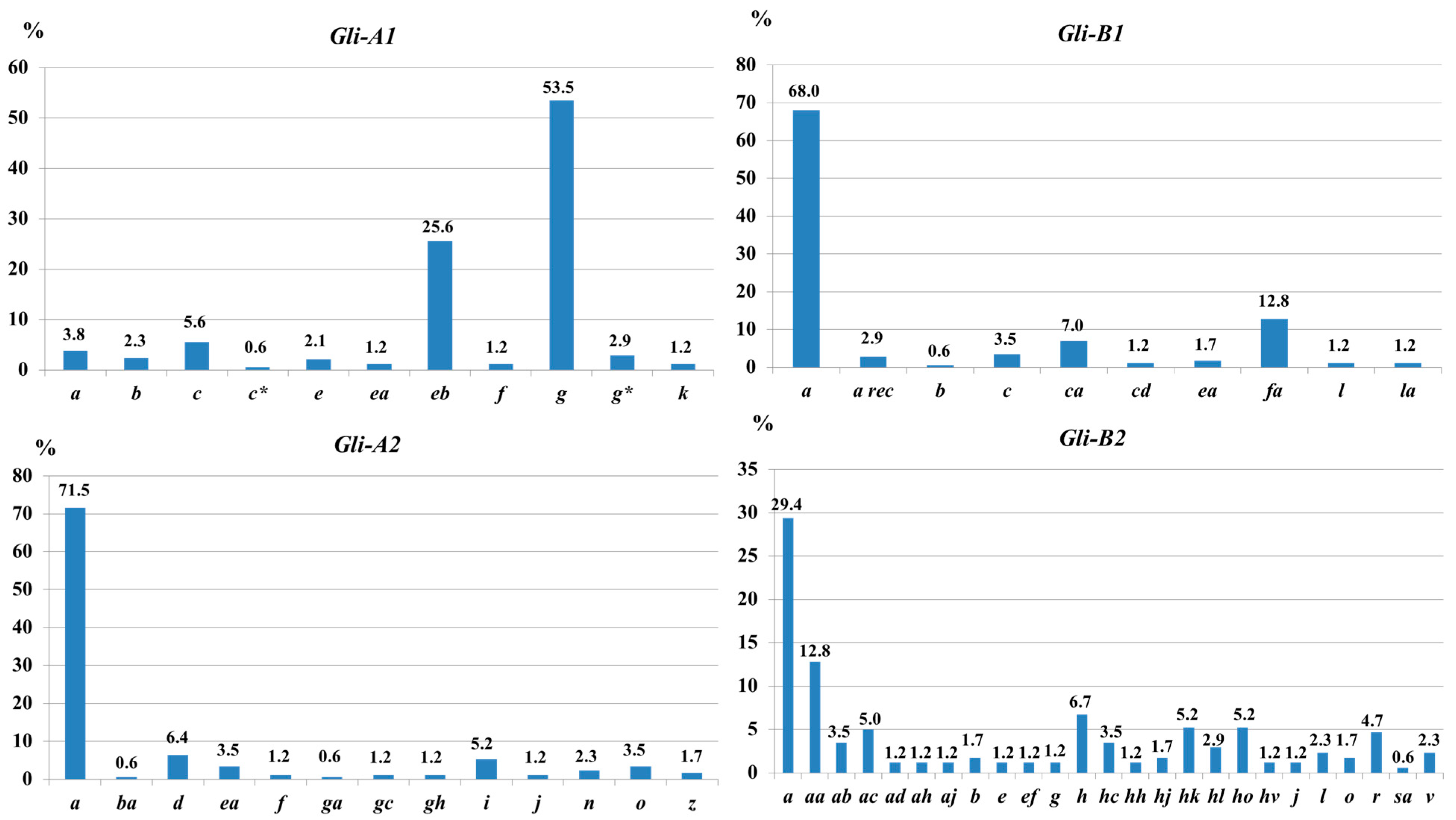

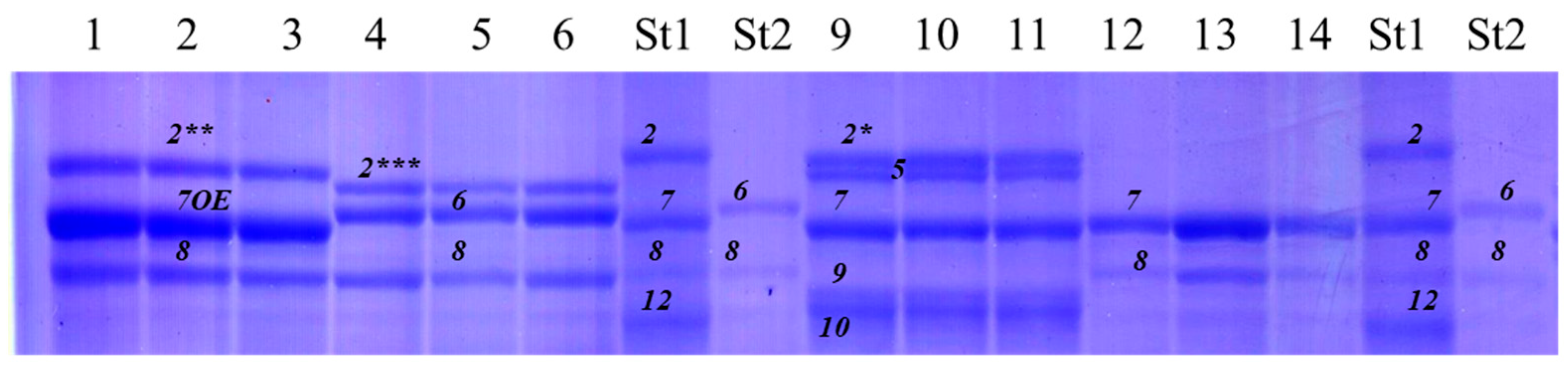

3.1.1. Gli-1 and Gli-2 Loci

3.1.2. Glu-1 Loci

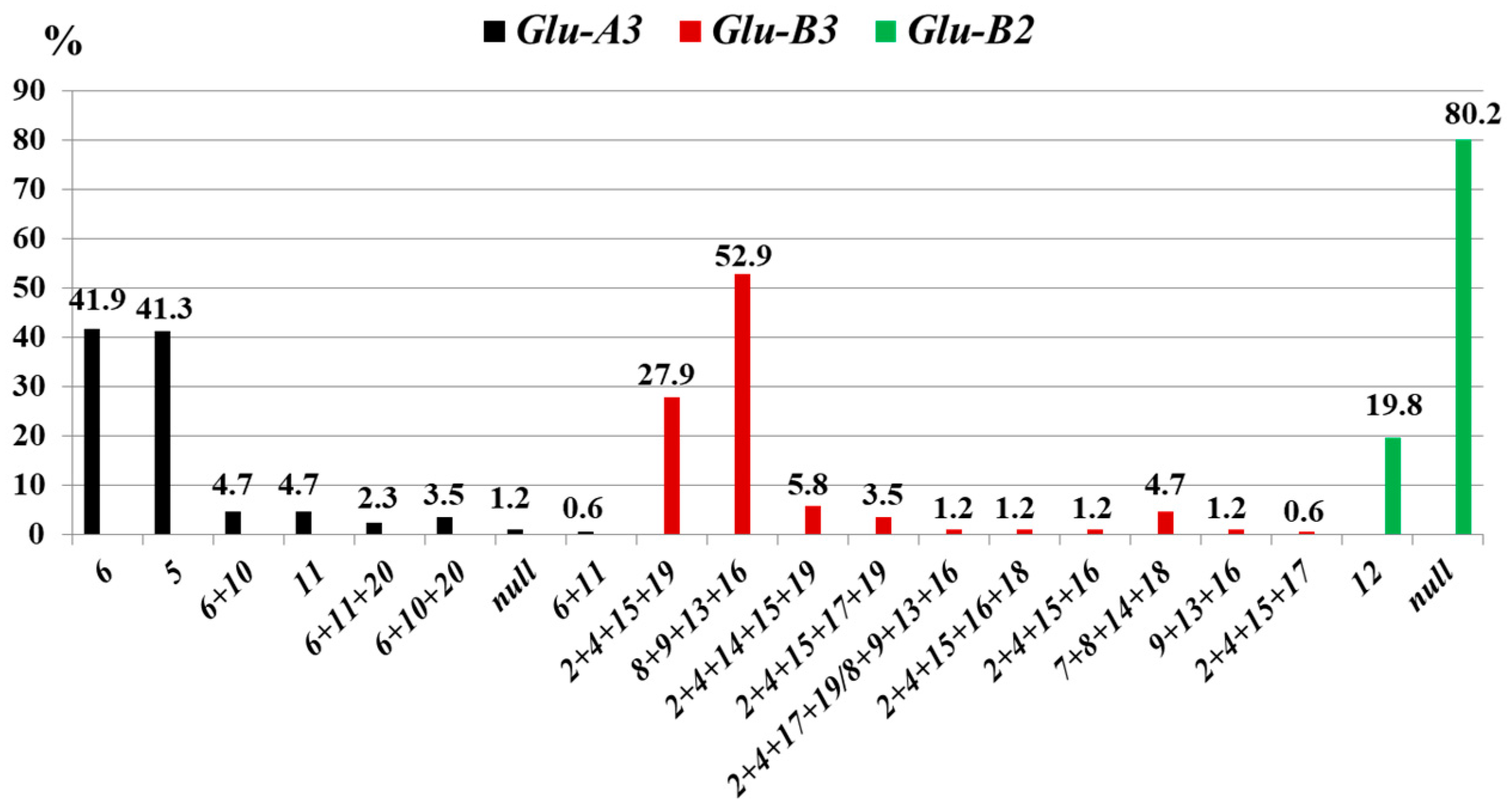

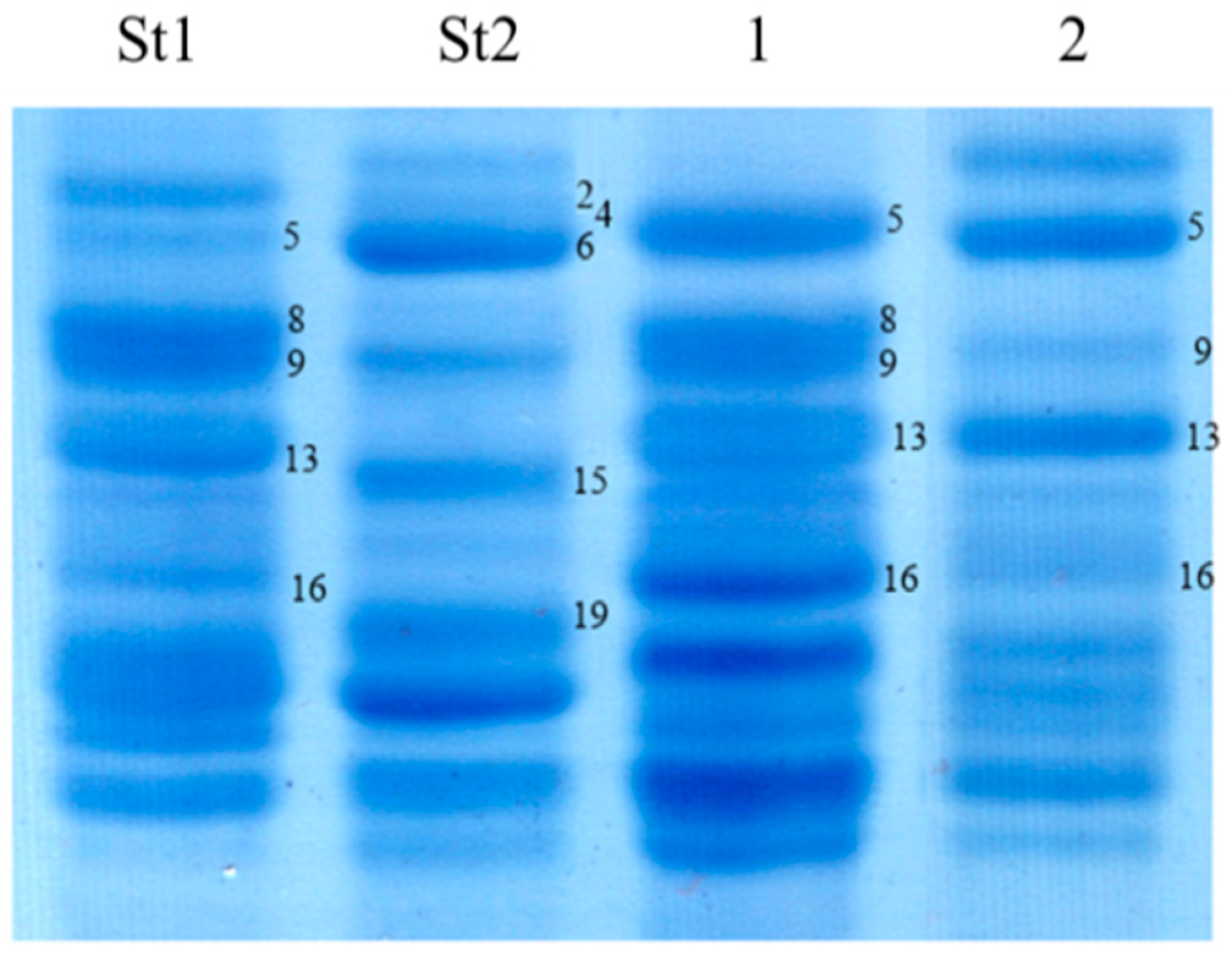

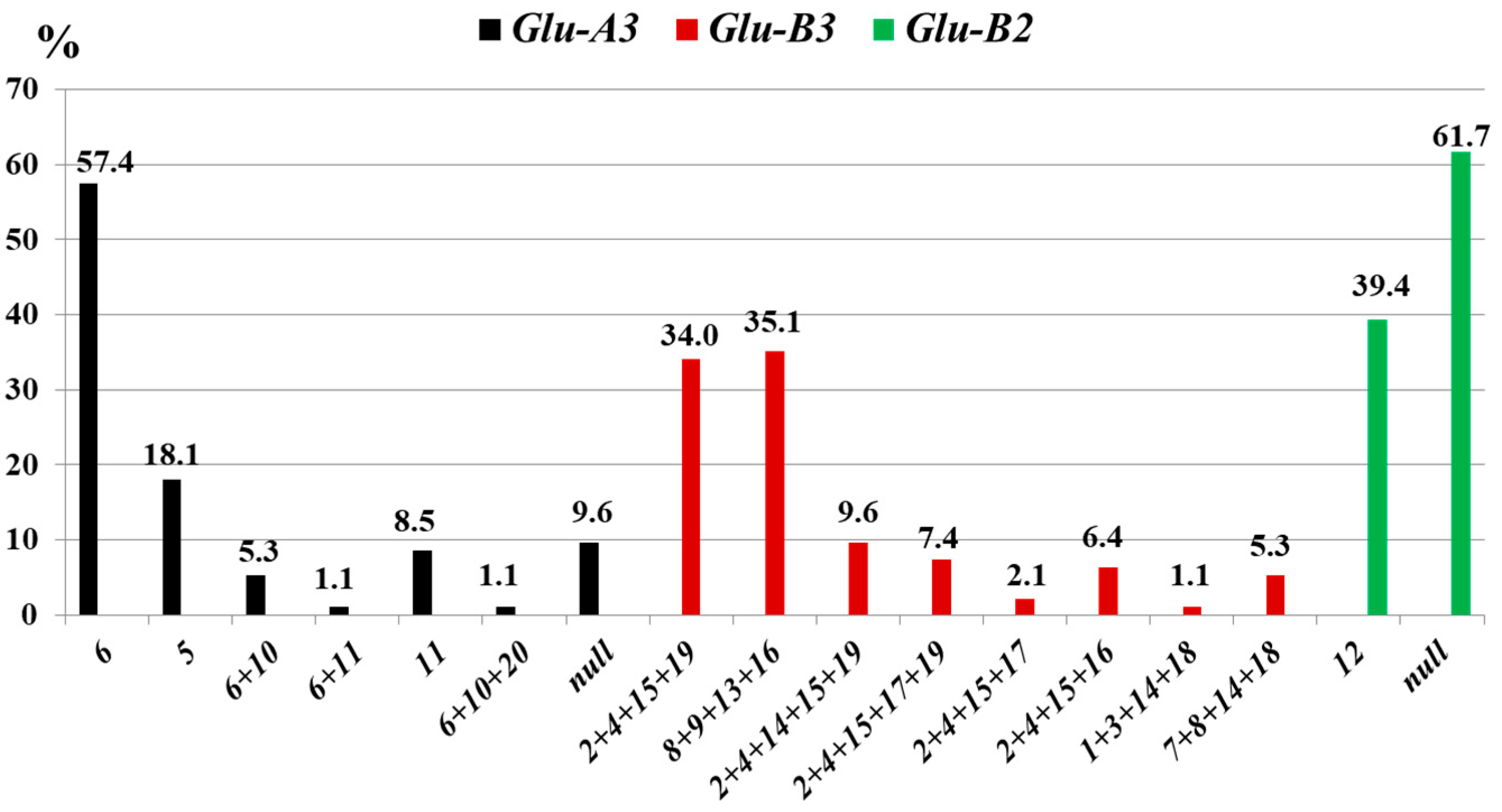

3.1.3. Glu-3 Loci

3.2. International Tetraploid Wheat Germplasm Collection

3.2.1. Gli-1 and Gli-2 Loci

3.2.2. Glu-1 Loci

3.2.3. Glu-3 Loci

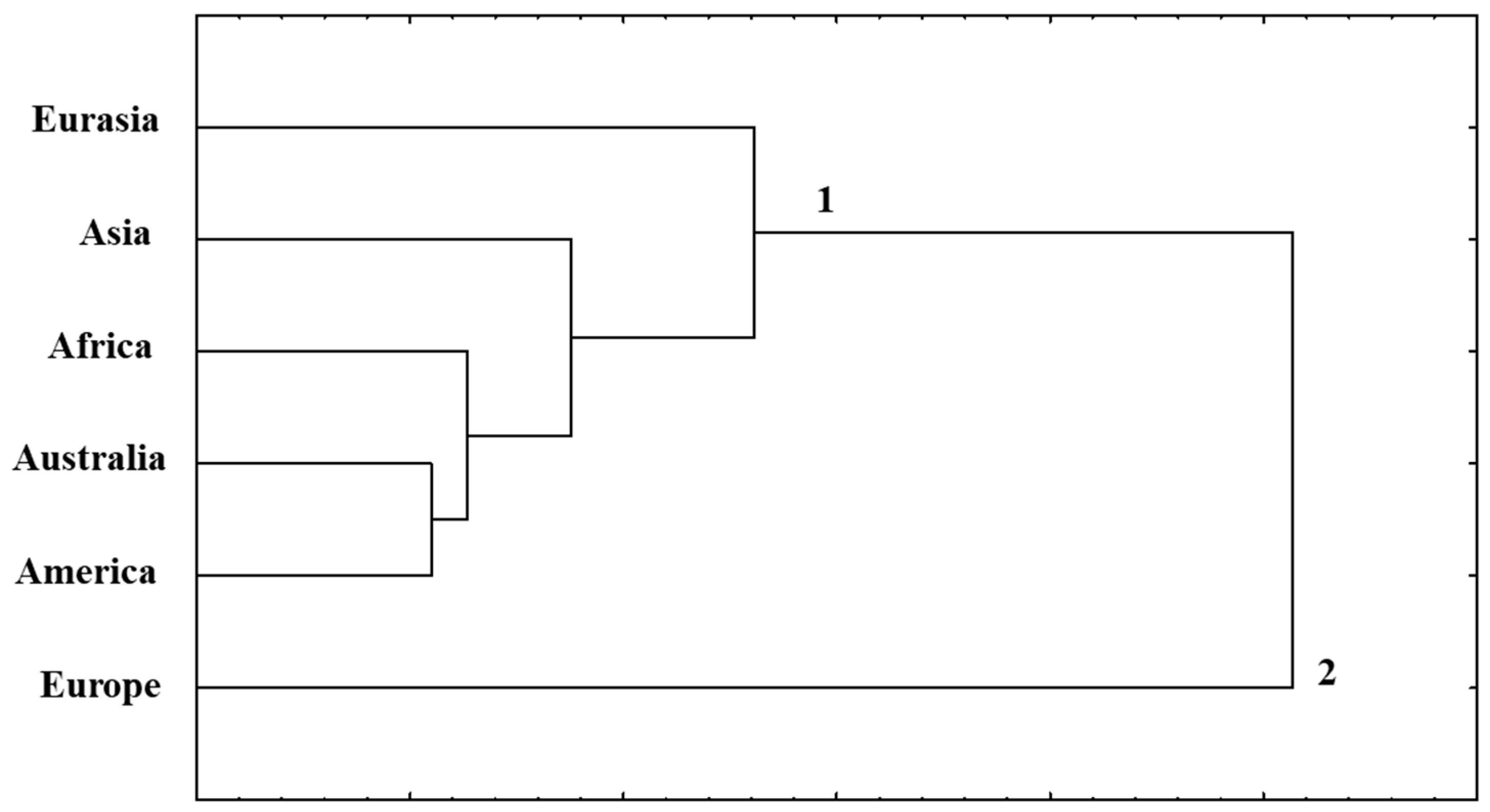

3.3. Statistical Analysis

3.4. Biochemical and Technological Analyses and Allelic Composition of Prolamins in Durum Wheat Breeding Lines from Kazakhstan

4. Discussion

4.1. Gli-1 and Gli-2 Loci

4.2. Glu-1 Loci

4.3. Glu-3 Loci

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colasuonno, P.; Marcotuli, I.; Blanco, A.; Maccaferri, M.; Condorelli, G.E.; Tuberosa, R.; Parada, R.; de Camargo, A.C.; Schwember, A.R.; Gadaleta, A. Carotenoid pigment content in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. var durum): An overview of quantitative trait loci and candidate genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, M. Durum wheat products—Recent advances. Foods 2022, 11, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Halford, N.G.; Lafiandra, D. Genetics of wheat gluten proteins. Adv. Genet. 2003, 49, 111–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.; Giraldo, P. The influence of allelic variability of prolamins on gluten quality in durum wheat: An overview. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 101, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cros, D.; Wrigley, C.W.; Hare, R.A. Prediction of durum-wheat quality from gliadin-protein composition. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1982, 33, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yupsanis, T.; Moustakas, M. Relationship between quality, colour of glume and gliadin electrophoregrams in durum wheat. Plant Breed. 1988, 101, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Bernal, G.; Giraldo, P. An update of low molecular weight glutenin subunits in durum wheat relevant to breeding for quality. J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 83, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oak, M.D.; Tamhankar, S.A.; Rao, V.S.; Bhosale, S.B. Relationship of HMW, LMW glutenin subunits and γ-gliadins with gluten strength in Indian durum wheats. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2004, 13, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazco, R.; Peña, R.J.; Ammar, K.; Villegas, D.; Crossa, J.; Royo, C. Durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Mediterranean landraces as sources of variability for allelic combinations at Glu-1/Glu-3 loci affecting gluten strength and pasta cooking quality. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Taladriz, M.T.; Ruiz, M.; Martinez, M.C.; Vazquez, J.F.; Carrillo, J.M. Variation and classification of B low-molecular-weight glutenin subunit alleles in durum wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1997, 95, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombieri, S.; Bonarrigo, M.; Potestio, S.; Sestili, F.; Messina, B.; Russo, G.; Miceli, C.; Frangipane, B.; Genduso, M.; Delogu, C.; et al. Characterization among and within Sicilian tetraploid wheat landraces by gluten protein analysis for traceability purposes. Plants 2024, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragues, M.; Zarco-Hernández, J.; Moralejo, M.A.; Royo, C. Genetic diversity of glutenin protein subunits composition in durum wheat landraces [Triticum turgidum ssp. turgidum convar. durum (Desf.) MacKey] from the Mediterranean basin. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2006, 53, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncallo, P.F.; Guzmán, C.; Larsen, A.O.; Achilli, A.L.; Dreisigacker, S.; Molfese, E.; Astiz, V.; Echenique, V. Allelic variation at glutenin loci (Glu-1, Glu-2 and Glu-3) in a worldwide durum wheat collection and its effect on quality attributes. Foods 2021, 10, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, N.V.; Mitrofanova, O.P.; Liapounova, O.A.; Kudryavtsev, A.M. Global diversity of durum wheat Triticum durum Desf. for alleles of gliadin-coding loci. Russ. J. Genet. 2010, 46, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, E.A.; Vázquez, F.J.; Giraldo, P.; Carrillo, J.M.; Benavente, E.; Rodríguez-Quijano, M. Allelic variation for prolamins in Spanish durum wheat landraces and its relationship with quality traits. Agronomy 2020, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherdouh, A.; Khelifi, D.; Carrillo, J.M.; Nieto-Taladriz, M.T. The high and low molecular weight glutenin subunit polymorphism of Algerian durum wheat landraces and old cultivars. Plant Breed. 2005, 124, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, S.E.; Cogliatti, M.; Ponzio, N.R.; Seghezzo, M.L.; Molfese, E.R.; Rogers, W.J. Genetic variation for grain protein components and industrial quality of durum wheat cultivars sown in Argentina. J. Cereal Sci. 2004, 40, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegdali, Y.; Ouabbou, H.; Essamadi, A.; Cervantes, F.; Ibba, M.I.; Guzmán, C. Assessment of the glutenin subunits diversity in a durum wheat (T. turgidum ssp. durum) collection from Morocco. Agronomy 2020, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.; Carvalho, C.; Carnide, V.; Guedes-Pinto, H.; Igrejas, G. Towards allelic diversity in the storage proteins of old and currently growing tetraploid and hexaploid wheats in Portugal. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011, 58, 1051–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.W.; Quick, J.S. A modified screening test for rapid estimation of a gluten strength in early generation durum wheat breeding lines. Cereal Chem. 1983, 60, 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiltchouk, N.S.; Gaponov, S.N.; Yeremenko, L.V.; Parshikova, T.M.; Popova, V.M.; Tsetva, N.M.; Shutareva, G.I. Gluten strength estimation during durum wheat breeding (Triticum durum Desf.). Agrar. Bull. South-East 2009, 3, 34–40. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Shepherd, K.; Cornish, G. A simplified SDS-PAGE procedure for separating. J. Cereal Sci. 1991, 14, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metakovsky, E.V.; Novoselskaya, A.Y. Gliadin allele identification in common wheat. 1. Methodological aspects of the analysis of gliadin pattern by one-dimensional polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis. J. Genet. Breed. 1991, 45, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utebayev, M.; Dashkevich, S.; Kunanbayev, K.; Bome, N.; Sharipova, B.; Shavrukov, Y. Genetic polymorphism of glutenin subunits with high molecular weight and their role in grain and dough qualities of spring bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) from Northern Kazakhstan. Acta Physiol. Plant 2019, 41, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, N.V.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Kudryavtsev, A.M. Catalogue of alleles of gliadin-coding loci in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.). Biochimie 2012, 94, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, P.I.; Lawrence, G.J. Catalogue of alleles for the complex loci Glu-A1, Glu-B1 and Glu-D1 which code for high-molecular-weight subunits of glutenin in hexaploid wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 1983, 11, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, R.A.; Yamazaki, Y.; Dubkovsky, J.; Rogers, J.; Morriss, C.; Appels, R.; Xia, X.C. Catalogue of Gene Symbols for Wheat. In Proceedings of the 12th International Wheat Genetics Symposium, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 September 2013; Available online: https://graingenes.org/GG3/sites/default/files/Catalogue%20of%20Gene%20Symbols%20for%20Wheat%20-%202013%20edition.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Utebayev, M.U.; Dashkevich, S.M.; Kradetskaya, O.O.; Chilimova, I.V.; Bome, N.A. Assessment of the genetic diversity of the alleles of gliadin-coding loci in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) collections in Kazakhstan and Russia. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2024, 28, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakin, G.F. Biometry; Vysshaya Shkola: Moscow, Russia, 1990; 352p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rokitsky, P.F. Biological Statistics; University Press: Minsk, Belarus, 1973; 320p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Choi, Y.M.; Lee, M.C.; Hyun, D.Y.; Oh, S.; Jung, Y. Geographical comparison of genetic diversity in Asian landrace wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) germplasm based on high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, N.V.; Ganeva, G.D.; Popova, Z.G.; Landjeva, S.P.; Kudryavtsev, A.M. Gliadins of Bulgarian durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) landraces: Genetic diversity and geographical distribution. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2010, 57, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.S.; Rao, V.S.; Pandey, H.N. Allelic variation of gliadin and glutenins in genetic stocks and advance lines of Triticum turgidum var. durum. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2003, 63, 307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtsev, A.M.; Dedova, L.V.; Melnik, V.A.; Shishkina, A.A.; Upelniek, V.P.; Novoselskaya-Dragovich, A.Y. Genetic diversity of modern Russian durum wheat cultivars at the gliadin-coding loci. Russ. J. Genet. 2014, 50, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, M.J.; Batey, I.L. Protein and starch properties of some tetraploid wheats. Cereal Chem. 2003, 80, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneva, K.; Dragov, R. Storage proteins of Bulgarian varieties and advanced lines of durum wheat. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2024, 67, 708–716. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiriano, E.; Ruiz, M.; Fité, R.; Carrillo, J.M. Analysis of genetic variability in a sample of the durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Spanish collection based on gliadin markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2006, 53, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djukic, N.; Knezevic, D.S.; Novoselskaya-Dragovich, A.Y. Polymorphism of Gli-A1 alleles and quality properties in 21 durum wheat genotypes. Cereal Res. Commun. 2007, 35, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Carrillo, J.M. Linkage relationships between prolamin genes on chromosomes 1A and 1B in durum wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1993, 87, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailegiorgis, D.; Lee, C.A.; Yun, S.J. Allelic variation at the gliadin coding loci of improved Ethiopian durum wheat varieties. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 20, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhivotovsky, L.A. Population similarity measure for polymorphic characters. J. Gen. Biol. 1979, 40, 587–602. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Aguiriano, E.; Ruiz, M.; Fité, R.; Carrillo, J.M. Effects of N fertilisation, year and prolamin alleles on gluten quality in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. ssp. turgidum) landraces from Spain. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2009, 7, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, J.F.; Ruiz, M.; Nieto-Taladriz, M.T.; Albuquerque, M.M. Effects on gluten strength of low Mr glutenin subunits coded by alleles at Glu-A3 and Glu-B3 loci in durum wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 1996, 24, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallega, V.; Mello-Sampayo, T. Variation of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits among cultivars of Triticum turgidum L. from Portugal. Euphytica 1987, 3, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babay, E.; Hanana, M.; Mzid, R.; Slim-Amara, H.; Carrillo, J.M.; Rodriguez-Quijano, M. Influence of allelic prolamin variation and localities on durum wheat quality. J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 63, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Quijano, M.; Lucas, R.; Ruiz, M.; Giraldo, P.; Espi, A.; Carrillo, J.M. Allelic variation and geographical patterns of prolamins in the USDA-ARS Khorasan wheat germplasm collection. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, 2383–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raciti, C.N.; Doust, M.A.; Lombardo, G.M.; Boggini, G.; Pecetti, L. Characterization of durum wheat Mediterranean germplasm for high and low molecular weight glutenin subunits in relation with quality. Eur. J. Agron. 2003, 19, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkrar, F.; El-Haddoury, J.; Iraqi, D.; Bendaou, N.; Udupa, S.M. Allelic variation at high-molecular-weight and low-molecular-weight glutenin subunit genes in Moroccan bread wheat and durum wheat cultivars. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo, P.; Ruiz, M.; Ibba, M.I.; Morris, C.F.; Labuschagne, M.T.; Igrejas, G. Durum wheat storage protein composition and the role of LMW-GS in quality. In Wheat Quality for Improving Processing and Human Health; Igrejas, G., Ikeda, T., Guzmán, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 73–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupin, P.Y.; Bespalova, L.A.; Kroupina, A.Y.; Yanovsky, A.S.; Korobkova, V.A.; Ulyanov, D.S.; Karlov, G.I.; Divashuk, M.G. Association of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits with grain and pasta quality in spring durum wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Garg, S.; Sheikh, I.; Vyas, P.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Effect of wheat grain protein composition on end-use quality. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2771–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Espinosa, N.; Payne, T.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Cervantes, F.; Gonzalez-Santoyo, H.; Ammar, K.; Guzmán, C. Preliminary characterization for grain quality traits and high and low molecular weight glutenin subunits composition of durum wheat landraces from Iran and Mexico. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 88, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.A. Wheat Gene Catalogue, 2017–2024; GrainGenes: Davis, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://graingenes.org/GG3/sites/default/files/data_downloads/%20Catalogue%20of%20Gene%20Symbols%20for%20Wheat%20-%202017-2024.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Carrillo, J.M.; Martínez, M.C.; Moita Brites, C.; Nieto-Taladriz, M.T.; Vázquez, J.F. Relationship between endosperm proteins and quality in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. var. durum). In Durum Wheat Improvement in the Mediterranean Region: New Challenges; Royo, C., Nachit, M., di Fonzo, N., Araus, J.L., Eds.; Ciheam: Zaragoza, Spain, 2000; pp. 463–467. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M.C.; Ruiz, M.; Carrillo, J.M. Effects of different prolamin alleles on durum wheat quality properties. J. Cereal Sci. 2005, 41, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Huang, M.; Jiang, D. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer on quality characteristics of wheat with the absence of different individual high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GSs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, K.; Xu, L.; Wang, M.; Lei, H.; Duan, A. The end-use quality of wheat can be enhanced by optimal water management without incurring yield loss. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1030763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, C.; Carrillo, J.M. Influence of high molecular weight (HMW) and low molecular weight (LMW) glutenin subunits controlled by Glu-1 and Glu-3 loci on durum wheat quality. Cereal Chem. 2001, 78, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallanes-Lopez, A.M.; Ammar, K.; Morales-Dorantes, A.; González-Santoyo, H.; Crossa, J.; Guzmán, C. Grain quality traits of commercial durum wheat varieties and their relationships with drought stress and glutenins composition. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Loci | Tetraploid Wheat Collection | µ ± S | h ± S | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu-A1 | Kazakhstan | 3.66 ± 0.10 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.69 |

| International | 3.44 ± 0.05 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.50 | |

| Glu-B1 | Kazakhstan | 5.04 ± 0.48 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.45 |

| International | 9.63 ± 0.59 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.83 | |

| Gli-A1 | Kazakhstan | 6.43 ± 0.58 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 0.64 |

| International | 10.31 ± 0.72 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.80 | |

| Gli-B1 | Kazakhstan | 5.46 ± 0.53 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.51 |

| International | 14.40 ± 0.84 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.86 | |

| Gli-A2 | Kazakhstan | 6.60 ± 0.70 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.48 |

| International | 14.92 ± 1.06 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.80 | |

| Gli-B2 | Kazakhstan | 18.91 ± 1.15 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.88 |

| International | 27.29 ± 1.54 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.93 | |

| Gli-B5 | Kazakhstan | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.34 |

| International | 1.98 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.50 | |

| Glu-A3 | Kazakhstan | 5.04 ± 0.41 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.65 |

| International | 4.93 ± 0.33 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.63 | |

| Glu-B3 | Kazakhstan | 5.79 ± 0.53 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 0.63 |

| International | 6.20 ± 0.34 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.74 | |

| Glu-B2 | Kazakhstan | 1.80 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.32 |

| International | 2.00 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.48 |

| HMWG/Allele/γ-Gliadin | Stat. Index | Technological and Biochemical Traits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | GC | GI | SDSS | ||

| 1Ax1 | rA (χ2f) | 0.19 (2.81) | 0.18 (2.71) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.05) |

| rQ ± S | 0.43 ± 0.19 | 0.41 ± 0.19 | −0.03 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.27 | |

| 1Bx7 + 1By8 | rA (χ2f) | 0.09 (0.66) | 0.15 (1.80) | −0.03 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| rQ ± S | 0.37 ± 0.31 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | −0.01 ± 0.31 | −0.15 ± 0.41 | |

| Glu-A3a | rA (χ2f) | 0.17 (2.14) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.49 (19.11) | 0.42 (13.45) |

| rQ ± S | −0.39 ± 0.21 | 0.06 ± 0.23 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 0.87 ± 0.08 | |

| Glu-B3b | rA (χ2f) | 0.11 (0.96) | 0.09 (0.58) | 0.26 (5.39) | 0.37 (10.67) |

| rQ ± S | 0.27 ± 0.21 | −0.22 ± 0.22 | 0.55 ± 0.17 | −0.84 ± 0.12 | |

| Glu-B2b | rA (χ2f) | 0.18 (2.61) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.06 (0.33) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| rQ ± S | 0.48 ± 0.22 | 0.07 ± 0.25 | 0.22 ± 0.25 | 0.13 ± 0.30 | |

| γ45 | rA (χ2f) | 0.08 (0.49) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.52 (21.26) | 0.59 (27.15) |

| rQ ± S | −0.24 ± 0.24 | 0.07 ± 0.25 | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | |

| Loci | Eurasia | Asia | Africa | Australia | Europe | America |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µ ± Sµ | ||||||

| Gli-1, Gli-2 | 12.12 ± 0.75 | 10.68 ± 0.77 | 7.39 ± 0.65 | 3.93 ± 0.15 | 8.92 ± 0.56 | 4.46 ± 0.58 |

| Glu-1 | 4.78 ± 0.31 | 4.93 ± 0.31 | 4.51 ± 0.24 | 5.22 ± 0.39 | 8.86 ± 0.47 | 3.53 ± 0.28 |

| Glu-3 | 5.54 ± 0.42 | 4.59 ± 0.47 | 4.89 ± 0.43 | 5.30 ± 0.43 | 28.22 ± 1.41 | 4.21 ± 0.34 |

| h ± Sh | ||||||

| Gli-1, Gli-2 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.11 |

| Glu-1 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.04 |

| Glu-3 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 0.17 ± 0.09 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.04 |

| H | ||||||

| Gli-1, Gli-2 | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.59 |

| Glu-1 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.35 |

| Glu-3 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.45 |

| Regions | Eurasia | Asia | Africa | Australia | Europe | America |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurasia | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.08 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | |

| 0 | 176.5 (124.12) | 144.7 (119.41) | 57.25 (122.33) | 635.2 (125.28) | 90.92 (114.69) | |

| Asia | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | ||

| 0 | 61.86 (93.21) | 51.53 (83.51) | 149.86 (105.2) | 74.43 (83.51) | ||

| Africa | 0.49 ± 0.12 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.11 | |||

| 0 | 37.47 (63.69) | 110.07 (93.22) | 58.89 (62.43) | |||

| Australia | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.41 ± 0.14 | ||||

| 0 | 58.01 (81.07) | 45.82 (50.89) | ||||

| Europe | 0.51 ± 0.08 | |||||

| 0 | 125.65 (83.51) | |||||

| America | 0 |

| Regions | Eurasia | Asia | Africa | Australia | Europe | America |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurasia | 0 | 61.36 (45.64) | 207.10 (32.00) | 59.65 (33.41) | 229.28 (56.06) | 235.14 (45.64) |

| 30.00 (33.41) | 101.56 (40.29) | 57.77 (34.81) | 229.79 (127.63) | 139.11 (41.64) | ||

| Asia | 0 | 75.71 (30.58) | 36.31 (33.41) | 83.14 (56.06) | 135.72 (36.19) | |

| 16.51 (32.00) | 22.48 (27.69) | 43.92 (122.94) | 32.70 (32.00) | |||

| Africa | 0 | 53.69 (33.41) | 79.54 (56.06) | 93.92 (45.64) | ||

| 26.79 (33.41) | 120.63 (128.80) | 36.31 (38.93) | ||||

| Australia | 0 | 52.94 (57.34) | 59.67 (37.57) | |||

| 61.18 (122.94) | 29.72 (33.41) | |||||

| Europe | 0 | 170.06 (59.89) | ||||

| 180.04 (129.97) | ||||||

| America | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Utebayev, M.; Dashkevich, S.; Kradetskaya, O.; Chilimova, I.; Zhylkybaev, R.; Zhigula, T.; Shelayeva, T.; Khassanova, G.; Bulatova, K.; Tsygankov, V.; et al. Genetic Diversity of Prolamin Loci Related to Grain Quality in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) in Kazakhstan. Life 2026, 16, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010157

Utebayev M, Dashkevich S, Kradetskaya O, Chilimova I, Zhylkybaev R, Zhigula T, Shelayeva T, Khassanova G, Bulatova K, Tsygankov V, et al. Genetic Diversity of Prolamin Loci Related to Grain Quality in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) in Kazakhstan. Life. 2026; 16(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleUtebayev, Maral, Svetlana Dashkevich, Oksana Kradetskaya, Irina Chilimova, Ruslan Zhylkybaev, Tatyana Zhigula, Tatyana Shelayeva, Gulmira Khassanova, Kulpash Bulatova, Vladimir Tsygankov, and et al. 2026. "Genetic Diversity of Prolamin Loci Related to Grain Quality in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) in Kazakhstan" Life 16, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010157

APA StyleUtebayev, M., Dashkevich, S., Kradetskaya, O., Chilimova, I., Zhylkybaev, R., Zhigula, T., Shelayeva, T., Khassanova, G., Bulatova, K., Tsygankov, V., Amangeldin, M., & Shavrukov, Y. (2026). Genetic Diversity of Prolamin Loci Related to Grain Quality in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) in Kazakhstan. Life, 16(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010157