Positive Selection in Aggression-Linked Genes and Their Protein Interaction Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Investigated Genomic Regions

2.2. Genomic Data

2.3. Population Genetics Analysis

2.4. Functional Data

3. Results

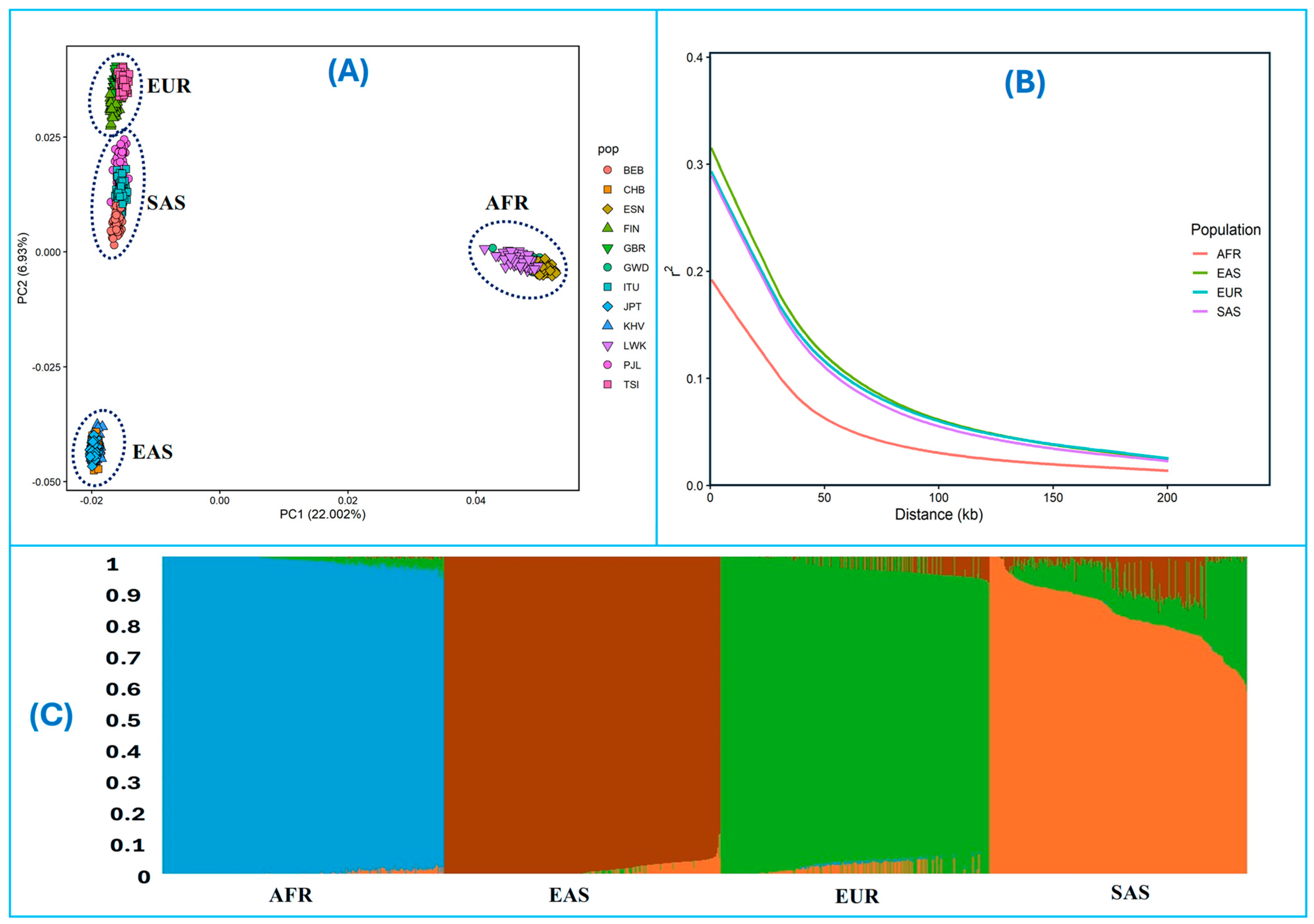

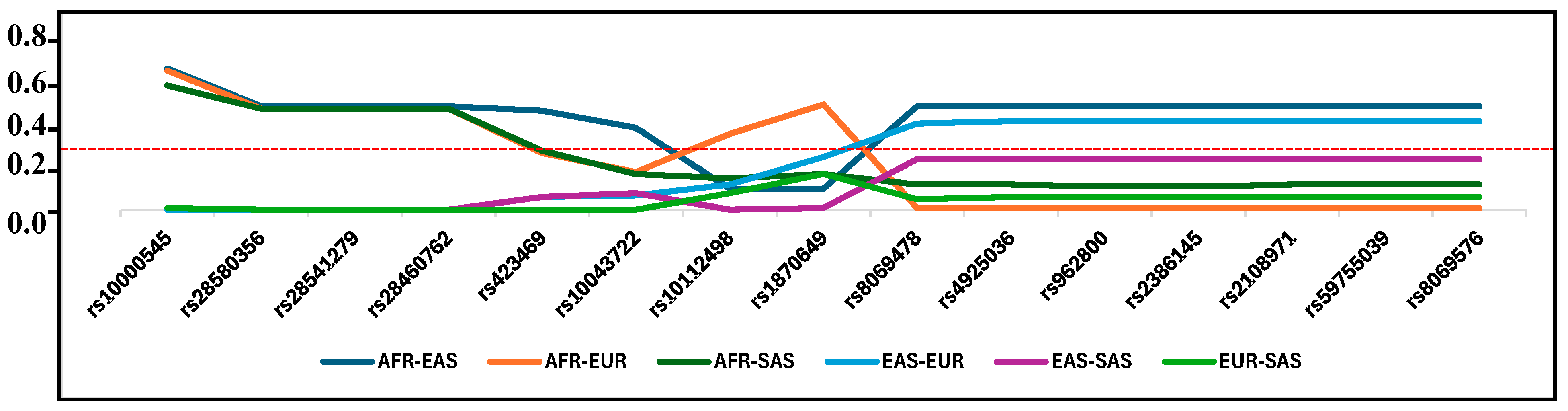

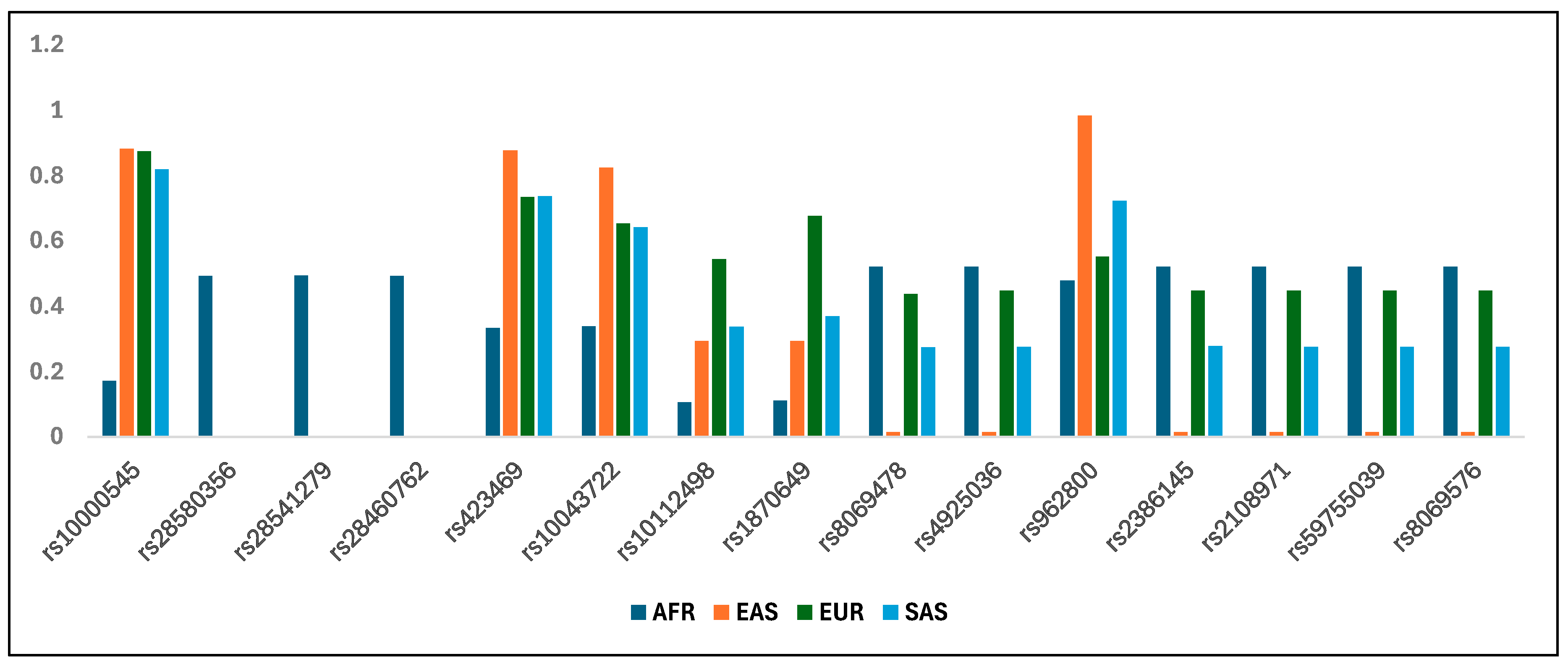

3.1. Positive Selection and Genetic Differentiation

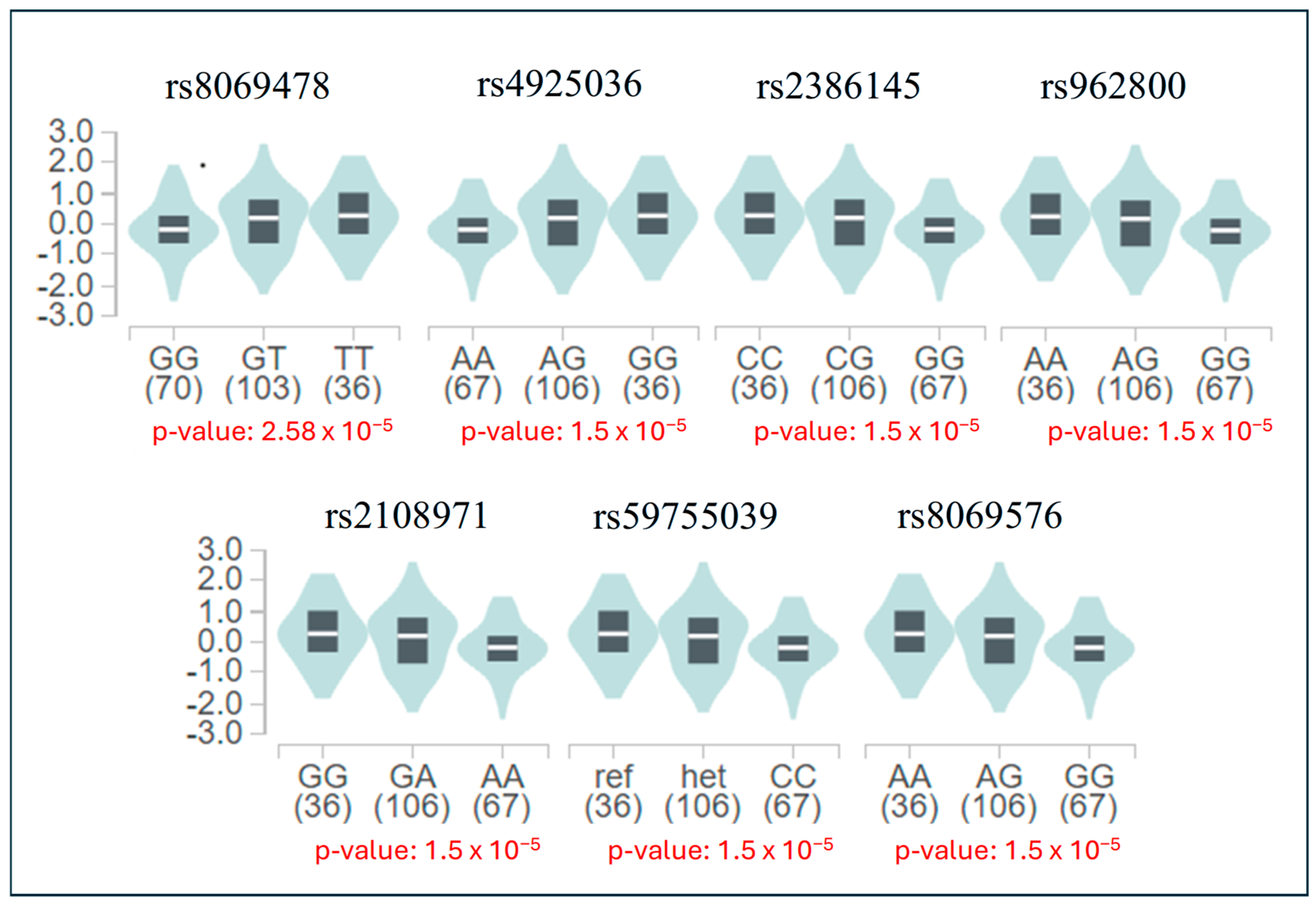

3.2. Functional Analyses Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang-James, Y.; Fernàndez-Castillo, N.; Hess, J.L.; Malki, K.; Glatt, S.J.; Cormand, B.; Faraone, S.V. An integrated analysis of genes and functional pathways for aggression in human and rodent models. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1655–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.; Jeong, J.; Jin, G.; Yeom, J.; Jekal, J.; Lee, S.I.; Cho, J.A.; Lee, S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, D.H.; et al. MAOA variants differ in oscillatory EEG & ECG activities in response to aggression-inducing stimuli. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2680. [Google Scholar]

- Reingle, J.M.; Maldonado-Molina, M.M.; Jennings, W.G.; Komro, K.A. Racial/ethnic differences in trajectories of aggression in a longitudinal sample of high-risk, urban youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendre, M.; Comasco, E.; Checknita, D.; Tiihonen, J.; Hodgins, S.; Nilsson, K.W. Associations between MAOA-uVNTR genotype, maltreatment, MAOA methylation, and alcohol consumption in young adult males. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammit, S.; Allebeck, P.; David, A.S.; Dalman, C.; Hemmingsson, T.; Lundberg, I.; Lewis, G. A longitudinal study of premorbid IQ Score and risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and other nonaffective psychoses. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, J.; Rautiainen, M.R.; Ollila, H.M.; Repo-Tiihonen, E.; Virkkunen, M.; Palotie, A.; Pietiläinen, O.; Kristiansson, K.; Joukamaa, M.; Lauerma, H.; et al. Genetic background of extreme violent behavior. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafikova, E.; Shadrina, M.; Slominsky, P.; Guekht, A.; Ryskov, A.; Shibalev, D.; Vasilyev, V. SLC6A3 (DAT1) as a Novel Candidate Biomarker Gene for Suicidal Behavior. Genes 2021, 12, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuvblad, C.; Baker, L.A. Human aggression across the lifespan: Genetic propensities and environmental moderators. Adv. Genet. 2011, 75, 171–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cases, O.; Seif, I.; Grimsby, J.; Gaspar, P.; Chen, K.; Pournin, S.; Müller, U.; Aguet, M.; Babinet, C.; Shih, J.C.; et al. Aggressive behavior and altered amounts of brain serotonin and norepinephrine in mice lacking MAOA. Science 1995, 268, 1763–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, H.G.; Nelen, M.; Breakefield, X.O.; Ropers, H.H.; van Oost, B.A. Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science 1993, 262, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Buckholtz, J.W.; Kolachana, B.; Hariri, A.R.; Pezawas, L.; Blasi, G.; Wabnitz, A.; Honea, R.; Verchinski, B.; Callicott, J.H.; et al. Neural mechanisms of genetic risk for impulsivity and violence in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 6269–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.; Roettger, M.E.; Shih, J.C. Contributions of the DAT1 and DRD2 genes to serious and violent delinquency among adolescents and young adults. Hum. Genet. 2007, 121, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, Y.D.; Kazantseva, A.V.; Enikeeva, R.F.; Mustafin, R.N.; Lobaskova, M.M.; Malykh, S.B.; Gilyasova, I.R.; Khusnutdinova, E.K. The Role of Oxytocin Receptor (OXTR) Gene Polymorphisms in the Development of Aggressive Behavior in Healthy Individuals. Russ. J. Genet. 2020, 56, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, S.; Mariotti, V.; Iofrida, C.; Pellegrini, S. Genes and Aggressive Behavior: Epigenetic Mechanisms Underlying Individual Susceptibility to Aversive Environments. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieri, R.L.; Churchill, S.E.; Franciscus, R.G.; Tan, J.; Hare, B. Craniofacial Feminization, Social Tolerance, and the Origins of Behavioral Modernity. Curr. Anthr. 2014, 55, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, C. Moral Origins: The Evolution of Virtue, Altruism, and Shame; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wrangham, R.W. Two types of aggression in human evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, T., Jr.; Zhao, M.; Saltzman, W. Hormones and the Evolution of Complex Traits: Insights from Artificial Selection on Behavior. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2016, 56, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang-James, Y.; Helminen, E.C.; Liu, J.; ENIGMA-ADHD Working Group; Franke, B.; Hoogman, M.; Faraone, S.V. Evidence for similar structural brain anomalies in youth and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A machine learning analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietsch, B.P. Genomic findings and their implications for the evolutionary social sciences. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2024, 45, 106596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries Robbé, M.; de Vogel, V.; Wever, E.C.; Douglas, K.S.; Nijman, H.L.I. Risk and protective factors for inpatient aggression. Crim. Justice Behav. 2016, 43, 1364–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D. The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penke, L.; Denisson, J.J.A.; Miller, G.F. The evolutionary genetics of personality. Eur. J. Personal. 2007, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, J.C.; Hegner, R.E.; Dufty, A.M.; Ball, G.F. The challenge hypothesis: Theoretical implications for patterns of testosterone secretion, mating systems, and breeding strategies. Am. Nat. 1990, 136, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.; Soravia, S.-M.; Dudeck, M.; Malli, L.; Fakhoury, M. Neurobiology of Aggression-Review of Recent Findings and Relationship with Alcohol and Trauma. Biology 2023, 12, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, H.R.; Sakharkar, A.J.; Teppen, T.L.; Berkel, T.D.M.; Pandey, S.C. The epigenetic landscape of alcoholism. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014, 115, 75–116. [Google Scholar]

- Philibert, R.A.; Penaluna, B.; White, T.; Shires, S.; Gunter, T.; Liesveld, J.; Erwin, C.; Hollenbeck, N.; Osborn, T. A pilot examination of the genome-wide DNA methylation signatures of subjects entering and exiting short-term alcohol dependence treatment programs. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-generation PLINK: Rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieson, I.; Lazaridis, I.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Patterson, N.; Roodenberg, S.A.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; Fernandes, D.; Novak, M.; et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 2015, 528, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voight, B.F.; Kudaravalli, S.; Wen, X.Q.; Pritchard, J.K. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e72. [Google Scholar]

- Szpiech, Z.A.; Hernandez, R.D. Selscan: An Efficient Multithreaded Program to Perform EHH-Based Scans for Positive Selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 2824–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Santander, C.G.; Martinez, A.R.; Meisner, J. Faster model-based estimation of ancestry proportions. bioRxiv 2024, 4, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Cockerham, C.C. Estimating f-statistics for the analysis of population-structure. Evolution 1984, 38, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardlie, K.G.; DeLuca, D.S.; Segre, A.V.; Sullivan, T.J.; Young, T.R.; Gelfand, E.T.; Trowbridge, C.A.; Maller, G.B.; Tukiainan, T.; Lek, M.; et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: Multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 2015, 348, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, A.P.; Hong, E.L.; Hariharan, M.; Cheng, Y.; Schaub, M.A.; Kasowski, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Park, J.; Hitz, B.C.; Weng, S.; et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaschl, H.; Göllner, T.; Morris, D.L. Positive selection acts on regulatory genetic variants in populations of European ancestry that affect ALDH2 gene expression. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, H.M.; Smolinska-Garbulowska, K.; Marzouka, N.; Khaliq, Z.; Wadelius, C.; Komorowski, J. funMotifs: Tissue-specific transcription factor motifs. bioRxiv 2019, 683722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milacic, M.; Beavers, D.; Conley, P.; Gong, C.; Gillespie, M.; Griss, J.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; May, B.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D672–D678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buniello, A.; MacArthur, J.A.L.; Cerezo, M.; Harris, L.W.; Hayhurst, J.; Malangone, C.; McMahon, A.; Morales, J.; Mountjoy, E.; Sollis, E.; et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1005–D1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentis, A.F.A.; Dardiotis, E.; Katsouni, E.; Chrousos, G.P. From warrior genes to translational solutions: Novel insights into monoamine oxidases (MAOs) and aggression. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.Y.; Zhou, X.Y.; Wang, Q.Q.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Lei, Y.P.; Ma, X.H.; Kong, P.; Shi, Y.; Jin, L.; et al. Mutations in the COPII vesicle component gene SEC24B are associated with human neural tube defects. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merte, J.; Jensen, D.; Wright, K.; Sarsfield, S.; Wang, Y.; Schekman, R.; Ginty, D.D. Sec24b selectively sorts Vangl2 to regulate planar cell polarity during neural tube closure. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavon, I.R. The E-cadherin-catenin complex in tumour metastasis: Structure, function and regulation. Eur. J. Cancer 2000, 36, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Liang, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, H.; Dong, Y.; Wu, L.; Gu, S.; Han, S. Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 2 Promotes Human Breast Cancer Cell Growth by Positively Regulating the MAPK/ERK Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.A.; Zander, U.; Fuchs, J.E.; Kreutz, C.; Watschinger, K.; Mueller, T.; Golderer, G.; Liedl, K.R.; Ralser, M.; Kräutler, B.; et al. A gatekeeper helix determines the substrate specificity of Sjögren-Larsson Syndrome enzyme fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase. Nat. Commun. 2014, 22, 4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, W.B.; Carney, G. Sjögren-Larsson syndrome: Diversity of mutations and polymorphisms in the fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH3A2). Hum. Mutat. 2005, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.; Bagby, R.M.; Wilson, A.A.; Miler, L.; Clark, M.; Rusjan, P.; Sacher, J.; Houle, S.; Meyer, J.H. Relationship of monoamine oxidase A binding to adaptive and maladaptive personality traits. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfs, E.M.L.; Van der Zwaag, W.; Priovoulos, N.; Klaus, J.; Schutter, D.J.L.G. The cerebellum during provocation and aggressive behaviour: A 7 T fMRI study. Imaging Neurosci. 2023, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagle, B.S.; Crawford, R.A.; Doorn, J.A. Biogenic Aldehyde-Mediated Mechanisms of Toxicity in Neurodegenerative Disease. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2019, 13, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population (Code) | Regional Population Description (Code) | Number of Individuals |

|---|---|---|

| Africa (AFR) | Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK) | 99 |

| Gambians from The Gambia (GWD) | 113 | |

| Esan in Nigeria (ESN) | 99 | |

| Europe (EUR) | British in England and Scotland (GBR) | 91 |

| Finnish in Finland (FIN) | 99 | |

| Toscani in Italia (TSI) | 107 | |

| South Asian (SAS) | Bengali from Bangladesh (BEB) | 86 |

| Indian Telugu from the UK (ITU) | 102 | |

| Punjabi from Lahore, Pakistan (PJL) | 96 | |

| East Asian (EAS) | Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB) | 103 |

| Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT) | 104 | |

| Kinhin Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (KHV) | 99 |

| Beneficial Allele/Alternate Allele | Location | iHS | Xp-EHH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Pop. | Score | Pop. | N/D | ||

| rs10000545-G/C | Intron, SEC24B | −2.96 | EUR | 3.59 | EAS-AFR EUR-AFR | C |

| rs28580356-T/C | Intron, SEC24B | 3.06 | AFR | 3.87 | C | |

| rs28541279-G/T | Intron, SEC24B | 3.04 | AFR | 3.85 | T | |

| rs28460762-C/A | Intron, SEC24B | 4.07 | AFR | 3.85 | A | |

| rs423469-G/C | Intron, CTNNA1 | −3.22 | AFR | 3.30 | EAS-AFR | C |

| rs10043722-A/G | Intron, CTNNA1 | −3.16 | AFR | 3.26 | G | |

| rs10112498-G/T | Intron, NCOA2 | 4.32 | AFR | 2.93 | EUR-AFR | T |

| rs1870649-C/G | Intron, NCOA2 | −3.50 | AFR | 3.21 | G | |

| rs8069478-T/G | Intron, ALDH3A2 | 3.00 | AFR | −3.23 | EUR-EAS | G |

| rs4925036-G/A | Intron, ALDH3A2 | 3.00 | AFR | −3.21 | A | |

| rs962800-G/A | Intron, ALDH3A2 | −3.07 | AFR | −2.99 | G | |

| rs2386145-C/G | Intron, ALDH3A2 | −2.93 | AFR | −3.06 | G | |

| rs2108971-G/A | Intron, ALDH3A2 | −2.81 | AFR | −3.20 | A | |

| rs59755039-CT/C | Intron, ALDH3A2 | −2.85 | AFR | −3.41 | C | |

| rs8069576-A/G | Intron, ALDH3A2 | −3.07 | AFR | −3.11 | G | |

| Beneficial Allele/Alternate Allele | Pairwise FST | Frequency Beneficial | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFR-EAS | AFR-EUR | AFR-SAS | EAS-EUR | EAS-SAS | EUR-SAS | AFR | EAS | EUR | SAS | |

| rs10000545-G/C | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.172 | 0.882 | 0.874 | 0.819 |

| rs28580356-T/C | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.492 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| rs28541279-G/T | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.494 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| rs28460762-C/A | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.492 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| rs423469-G/C | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.334 | 0.877 | 0.734 | 0.738 |

| rs10043722-A/G | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.339 | 0.824 | 0.653 | 0.641 |

| rs10112498-G/T | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.106 | 0.294 | 0.544 | 0.338 |

| rs1870649-C/G | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.111 | 0.294 | 0.677 | 0.37 |

| rs8069478-T/G | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.521 | 0.016 | 0.438 | 0.275 |

| rs4925036-G/A | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.521 | 0.016 | 0.449 | 0.276 |

| rs962800-G/A | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.479 | 0.984 | 0.551 | 0.722 |

| rs2386145-C/G | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.521 | 0.016 | 0.449 | 0.278 |

| rs2108971-G/A | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.521 | 0.016 | 0.449 | 0.276 |

| rs59755039-CT/C | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.521 | 0.016 | 0.449 | 0.276 |

| rs8069576-A/G | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.521 | 0.016 | 0.449 | 0.276 |

| eQTL | eGene | RegulomeDB | Chromatin State | Motifs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Rank | ||||

| rs10000545 | SEC24B, SEC24B-AS1, RBMXP4, SETP20 | 0.66703 | 1f | Active TSS, Flanking active TSS, Weak enhancer, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low | BCL6, ISL1, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B |

| rs28580356 | - | 0.51392 | 7 | Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low, | - |

| rs28541279 | - | 0.51392 | 7 | Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low, | - |

| rs28460762 | - | 0.51392 | 7 | Enhancers, Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low | - |

| rs423469 | AC034243.1, CTNNA1, SIL1 | 0.22271 | 1f | Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low | - |

| rs10043722 | AC034243.1, CTNNA1, SIL1 | 0.94667 | 1b | Genic enhancers, Enhancers, Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low | - |

| rs10112498 | - | 0.58955 | 5 | Enhancers, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low | - |

| rs1870649 | - | 0.18412 | 7 | Active TSS, Enhancers, Weak transcription, Quiescent/Low | ZNF384 |

| rs8069478 | RP11-311F12.1, ALDH3A2 | 0.55436 | 1f | Active TSS, Flanking active TSS, Enhancers, Weak transcription, Bivalent/Poised TSS, Weak repressed polycomb, Quiescent/Low | - |

| rs4925036 | RP11-311F12.1, ALDH3A2 | 0.66703 | 1f | Active TSS, Flanking active TSS, Enhancers, Weak transcription, Bivalent/Poised TSS, Weak repressed polycomb, Quiescent/Low | BATF, BATF3, DUXA, FOSL1 |

| rs962800 | RP11-311F12.1, ALDH3A2 | 0.66703 | 1f | Genic enhancers, Transcr. at 5’ and 3’, Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Repressed polycomb, Weak repressed polycomb, Heterochromatin, Quiescent/Low | GATA1 |

| rs2386145 | RP11-311F12.1, ALDH3A2 | 0.55436 | 1f | Genic enhancers, Enhancers, Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Weak repressed polycomb, Quiescent/Low | - |

| rs2108971 | RP11-311F12.1, ALDH3A2 | 0.51392 | 7 | Genic enhancers, Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Weak repressed polycomb, Quiescent/Low | - |

| rs59755039 | RP11-311F12.1, ALDH3A2 | 0.55436 | 1f | Genic enhancers, Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Weak repressed polycomb, Quiescent/Low | IRF1, STAT2 |

| rs8069576 | RP11-311F12.1, ALDH3A2 | 0.51392 | 7 | Strong transcription, Weak transcription, Weak repressed polycomb, Quiescent/Low | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Awadi, A.; Tolesa, Z.G.; Ben Slimen, H. Positive Selection in Aggression-Linked Genes and Their Protein Interaction Networks. Life 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010015

Awadi A, Tolesa ZG, Ben Slimen H. Positive Selection in Aggression-Linked Genes and Their Protein Interaction Networks. Life. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwadi, Asma, Zelalem Gebremariam Tolesa, and Hichem Ben Slimen. 2026. "Positive Selection in Aggression-Linked Genes and Their Protein Interaction Networks" Life 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010015

APA StyleAwadi, A., Tolesa, Z. G., & Ben Slimen, H. (2026). Positive Selection in Aggression-Linked Genes and Their Protein Interaction Networks. Life, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010015