Cells Co-Producing Insulin and Glucagon in Congenital Hyperinsulinism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

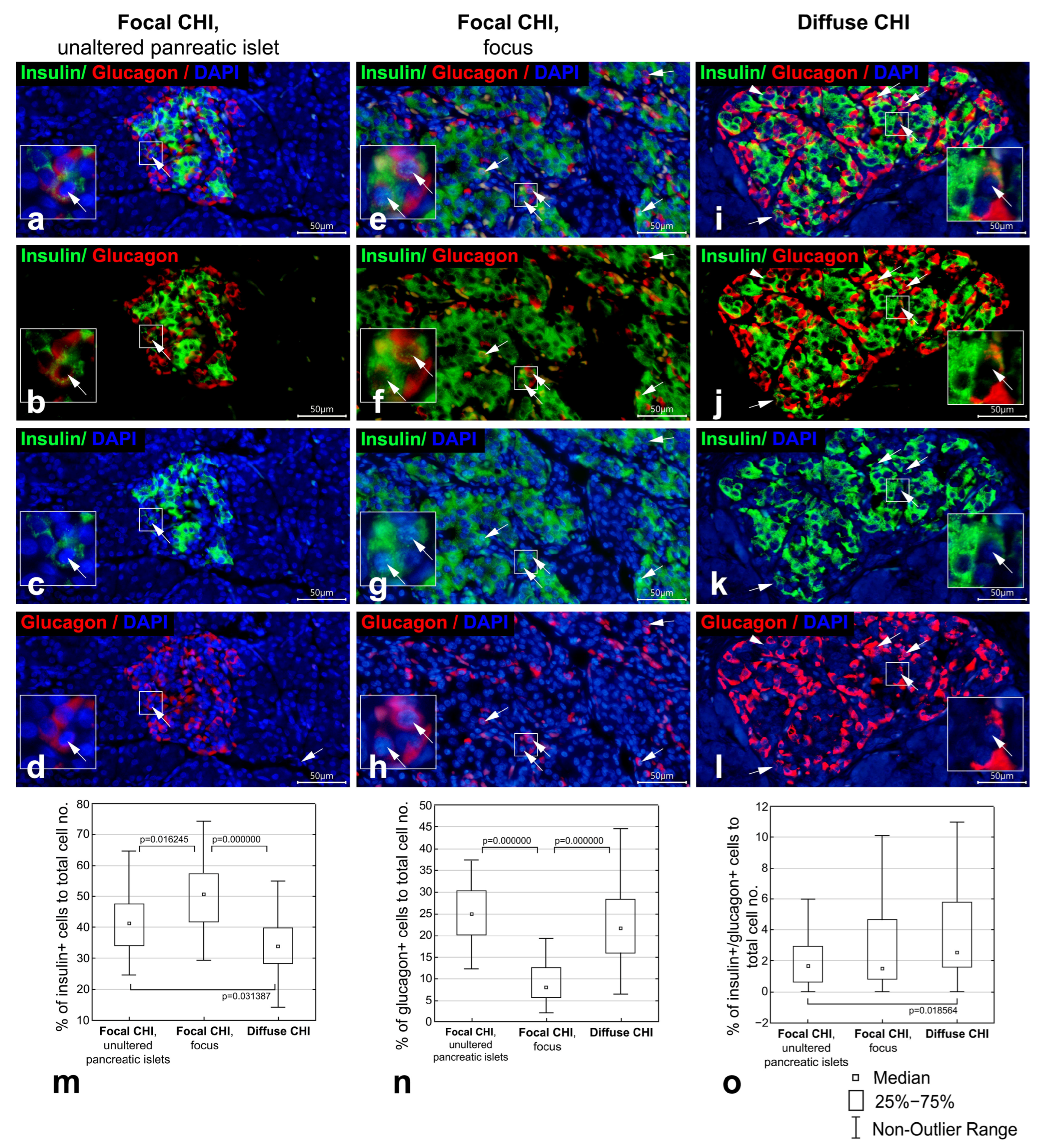

3.1. Co-Localization of Insulin and Glucagon in Diffuse and Focal CHI

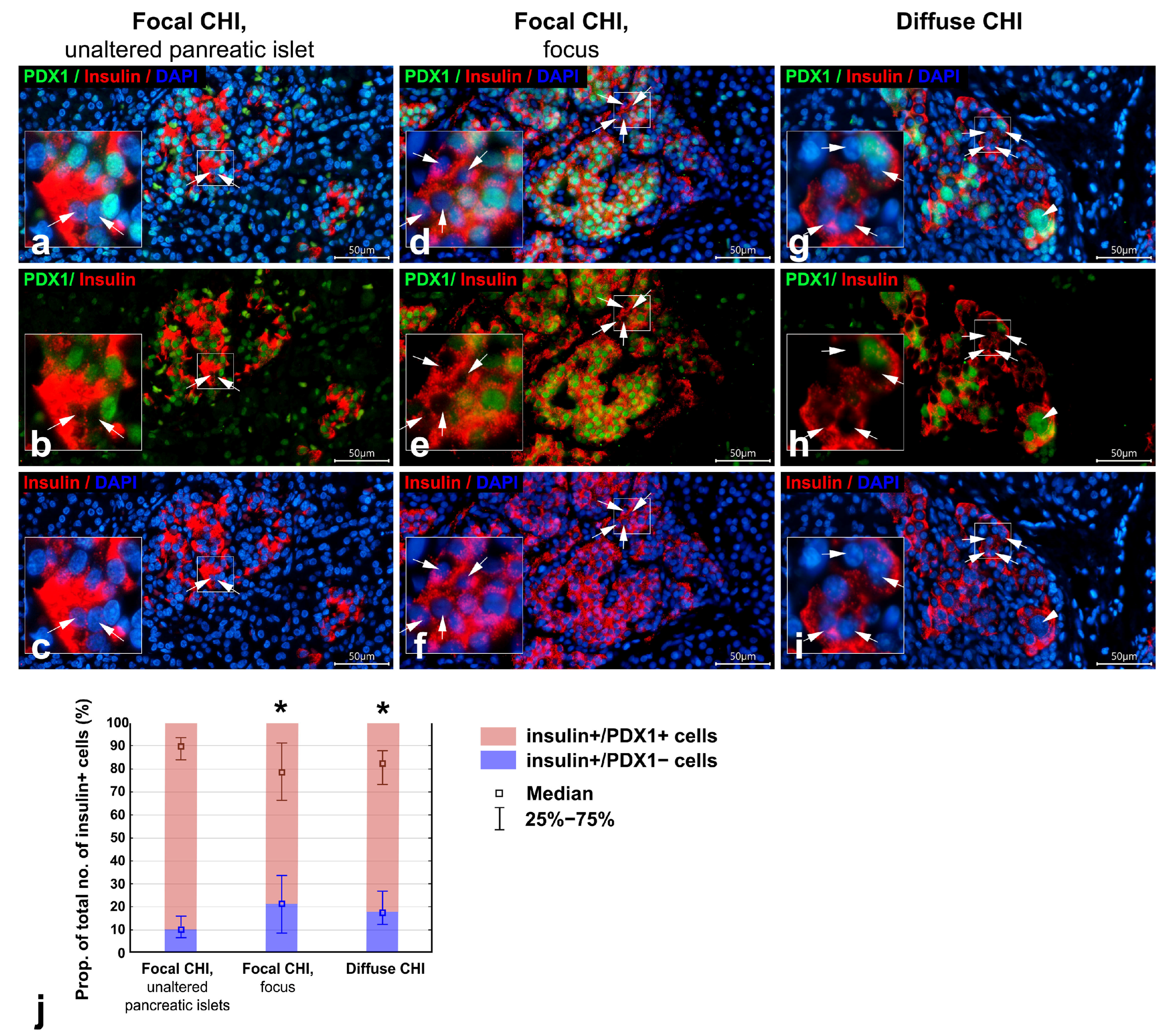

3.2. Co-Localization of PDX1 with Insulin and Glucagon in Diffuse and Focal CHI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenfeld, E.; Ganguly, A.; De Leon, D.D. Congenital Hyperinsulinism Disorders: Genetic and Clinical Characteristics. In Proceedings of the American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 181, pp. 682–692. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.S.; Stanley, C.A.; De Leon, D.D. Congenital Hyperinsulinism: An Historical Perspective. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2022, 95, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajravelu, M.E.; De León, D.D. Genetic Characteristics of Patients with Congenital Hyperinsulinism. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2018, 30, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, D.; Laver, T.W.; Dastamani, A.; Senniappan, S.; Houghton, J.A.L.; Shaikh, G.; Cheetham, T.; Mushtaq, T.; Kapoor, R.R.; Randell, T. Using Referral Rates for Genetic Testing to Determine the Incidence of a Rare Disease: The Minimal Incidence of Congenital Hyperinsulinism in the UK Is 1 in 28,389. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewat, T.I.; Johnson, M.B.; Flanagan, S.E. Congenital Hyperinsulinism: Current Laboratory-Based Approaches to the Genetic Diagnosis of a Heterogeneous Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 873254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.R.; Flanagan, S.E.; Arya, V.B.; Shield, J.P.; Ellard, S.; Hussain, K. Clinical and Molecular Characterisation of 300 Patients with Congenital Hyperinsulinism. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 168, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, K.E.; Becker, S.; Boyajian, L.; Shyng, S.-L.; MacMullen, C.; Hughes, N.; Ganapathy, K.; Bhatti, T.; Stanley, C.A.; Ganguly, A. Genotype and Phenotype Correlations in 417 Children with Congenital Hyperinsulinism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E355–E363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, A.; Gepts, W.; Saudubray, J.-M.; Bonnefont, J.P.; Klöppel, G. Diffuse and Focal Nesidioblastosis: A Clinicopathological Study of 24 Patients with Persistent Neonatal Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1989, 13, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahier, J.; Fält, K.; Müntefering, H.; Becker, K.; Gepts, W.; Falkmer, S. The Basic Structural Lesion of Persistent Neonatal Hypoglycaemia with Hyperinsulinism: Deficiency of Pancreatic D Cells or Hyperactivity of B Cells? Diabetologia 1984, 26, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahier, J.; Guiot, Y.; Sempoux, C. Morphologic Analysis of Focal and Diffuse Forms of Congenital Hyperinsulinism. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Pediatric Surgery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 20, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sempoux, C.; Guiot, Y.; Jaubert, F.; Rahier, J. Focal and Diffuse Forms of Congenital Hyperinsulinism: The Keys for Differential Diagnosis. Endocr. Pathol. 2004, 15, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempoux, C.; Capito, C.; Bellanné-Chantelot, C.; Verkarre, V.; De Lonlay, P.; Aigrain, Y.; Fekete, C.; Guiot, Y.; Rahier, J. Morphological Mosaicism of the Pancreatic Islets: A Novel Anatomopathological Form of Persistent Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia of Infancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 3785–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrofanova, L.B.; Perminova, A.A.; Ryzhkova, D.V.; Sukhotskaya, A.A.; Bairov, V.G.; Nikitina, I.L. Differential Morphological Diagnosis of Various Forms of Congenital Hyperinsulinism in Children. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 710947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lonlay, P.; Fournet, J.-C.; Rahier, J.; Gross-Morand, M.-S.; Poggi-Travert, F.; Foussier, V.; Bonnefont, J.-P.; Brusset, M.-C.; Brunelle, F.; Robert, J.-J. Somatic Deletion of the Imprinted 11p15 Region in Sporadic Persistent Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia of Infancy Is Specific of Focal Adenomatous Hyperplasia and Endorses Partial Pancreatectomy. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, R.J.; Han, B.; Jennings, R.E.; Berry, A.A.; Stevens, A.; Mohamed, Z.; Sugden, S.A.; De Krijger, R.; Cross, S.E.; Johnson, P.P. V Altered Phenotype of β-Cells and Other Pancreatic Cell Lineages in Patients with Diffuse Congenital Hyperinsulinism in Infancy Caused by Mutations in the ATP-Sensitive K-Channel. Diabetes 2015, 64, 3182–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.-C.; Sharma, A.; Hasenkamp, W.; Ilkova, H.; Patane, G.; Laybutt, R.; Bonner-Weir, S.; Weir, G.C. Chronic Hyperglycemia Triggers Loss of Pancreatic β Cell Differentiation in an Animal Model of Diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 14112–14121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brereton, M.F.; Iberl, M.; Shimomura, K.; Zhang, Q.; Adriaenssens, A.E.; Proks, P.; Spiliotis, I.I.; Dace, W.; Mattis, K.K.; Ramracheya, R. Reversible Changes in Pancreatic Islet Structure and Function Produced by Elevated Blood Glucose. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, N.A.; Kushner, J.A.; Glandt, M.; Kitamura, T.; Brillantes, A.-M.B.; Herold, K.C. Effects of Autoimmunity and Immune Therapy on β-Cell Turnover in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2006, 55, 3238–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talchai, C.; Xuan, S.; Lin, H.V.; Sussel, L.; Accili, D. Pancreatic β Cell Dedifferentiation as a Mechanism of Diabetic β Cell Failure. Cell 2012, 150, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; York, N.W.; Nichols, C.G.; Remedi, M.S. Pancreatic β Cell Dedifferentiation in Diabetes and Redifferentiation Following Insulin Therapy. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.J.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, E.; Cox, A.R.; Kushner, J.A. Low-Level Insulin Content within Abundant Non-β Islet Endocrine Cells in Long-Standing Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2019, 68, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiron, P.; Wiberg, A.; Kuric, E.; Krogvold, L.; Jahnsen, F.L.; Dahl-Jørgensen, K.; Skog, O.; Korsgren, O. Characterisation of the Endocrine Pancreas in Type 1 Diabetes: Islet Size Is Maintained but Islet Number Is Markedly Reduced. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2019, 5, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijker, H.S.; Song, H.; Ellenbroek, J.H.; Roefs, M.M.; Engelse, M.A.; Bos, E.; Koster, A.J.; Rabelink, T.J.; Hansen, B.C.; Clark, A. Loss of β-Cell Identity Occurs in Type 2 Diabetes and Is Associated with Islet Amyloid Deposits. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2928–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Moin, A.S.; Dhawan, S.; Cory, M.; Butler, P.C.; Rizza, R.A.; Butler, A.E. Increased Frequency of Hormone Negative and Polyhormonal Endocrine Cells in Lean Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3628–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.G.; Marshall, H.L.; Rigby, R.; Huang, G.C.; Amer, A.; Booth, T.; White, S.; Shaw, J.A.M. Expression of Mesenchymal and α-Cell Phenotypic Markers in Islet β-Cells in Recently Diagnosed Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3818–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, K.; Cosgrove, K.E. From Congenital Hyperinsulinism to Diabetes Mellitus: The Role of Pancreatic Β-cell KATP Channels. Pediatr. Diabetes 2005, 6, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, I.; Raskin, J.; Arnoux, J.-B.; De Leon, D.D.; Weinzimer, S.A.; Hammer, M.; Kendall, D.M.; Thornton, P.S. Congenital Hyperinsulinism in Infancy and Childhood: Challenges, Unmet Needs and the Perspective of Patients and Families. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoux, J.-B.; Verkarre, V.; Saint-Martin, C.; Montravers, F.; Brassier, A.; Valayannopoulos, V.; Brunelle, F.; Fournet, J.-C.; Robert, J.-J.; Aigrain, Y. Congenital Hyperinsulinism: Current Trends in Diagnosis and Therapy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudswaard, W.B.; Houthoff, H.J.; Koudstaal, J.; Zwierstra, R.P. Nesidioblastosis and Endocrine Hyperplasia of the Pancreas: A Secondary Phenomenon. Hum. Pathol. 1986, 17, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaing, M.; Duvillié, B.; Quemeneur, E.; Basmaciogullari, A.; Scharfmann, R. Ex Vivo Analysis of Acinar and Endocrine Cell Development in the Human Embryonic Pancreas. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2005, 234, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.A.; Kobberup, S.; Wong, R.; Lopez, A.D.; Quayum, N.; Still, T.; Kutchma, A.; Jensen, J.N.; Gianani, R.; Beattie, G.M. Global Gene Expression Profiling and Histochemical Analysis of the Developing Human Fetal Pancreas. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, M.J.; Asadi, A.; Wang, R.; Ao, Z.; Warnock, G.L.; Kieffer, T.J. Immunohistochemical Characterisation of Cells Co-Producing Insulin and Glucagon in the Developing Human Pancreas. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithovius, V.; Saarimäki-Vire, J.; Balboa, D.; Ibrahim, H.; Montaser, H.; Barsby, T.; Otonkoski, T. SUR1-Mutant IPS Cell-Derived Islets Recapitulate the Pathophysiology of Congenital Hyperinsulinism. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Correa-Medina, M.; Ricordi, C.; Edlund, H.; Diez, J.A. Endocrine Cell Clustering during Human Pancreas Development. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009, 57, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riopel, M.; Li, J.; Fellows, G.F.; Goodyer, C.G.; Wang, R. Ultrastructural and Immunohistochemical Analysis of the 8-20 Week Human Fetal Pancreas. Islets 2014, 6, e982949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniru, O.E.; Kadolsky, U.; Kannambath, S.; Vaikkinen, H.; Fung, K.; Dhami, P.; Persaud, S.J. Single-Cell Transcriptomic and Spatial Landscapes of the Developing Human Pancreas. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahm, J.; Kumar, D.; Andrade, J.A.F.; Arany, E.; Hill, D.J. Bi-Hormonal Endocrine Cell Presence Within the Islets of Langerhans of the Human Pancreas Throughout Life. Cells 2025, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijker, H.S.; Ravelli, R.B.G.; Mommaas-Kienhuis, A.M.; van Apeldoorn, A.A.; Engelse, M.A.; Zaldumbide, A.; Bonner-Weir, S.; Rabelink, T.J.; Hoeben, R.C.; Clevers, H. Conversion of Mature Human β-Cells into Glucagon-Producing α-Cells. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruin, J.E.; Erener, S.; Vela, J.; Hu, X.; Johnson, J.D.; Kurata, H.T.; Lynn, F.C.; Piret, J.M.; Asadi, A.; Rezania, A. Characterization of Polyhormonal Insulin-Producing Cells Derived in Vitro from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cell Res. 2014, 12, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, H.A.; Parent, A.V.; Ringler, J.J.; Hennings, T.G.; Nair, G.G.; Shveygert, M.; Guo, T.; Puri, S.; Haataja, L.; Cirulli, V. Controlled Induction of Human Pancreatic Progenitors Produces Functional Beta-like Cells in Vitro. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 1759–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigha, I.I.; Abdelalim, E.M. NKX6. 1 Transcription Factor: A Crucial Regulator of Pancreatic β Cell Development, Identity, and Proliferation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papizan, J.B.; Singer, R.A.; Tschen, S.-I.; Dhawan, S.; Friel, J.M.; Hipkens, S.B.; Magnuson, M.A.; Bhushan, A.; Sussel, L. Nkx2. 2 Repressor Complex Regulates Islet β-Cell Specification and Prevents β-to-α-Cell Reprogramming. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2291–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Herrera, P.L.; Carreira, C.; Bonnavion, R.; Seigne, C.; Calender, A.; Bertolino, P.; Zhang, C.X. α Cell–Specific Men1 Ablation Triggers the Transdifferentiation of Glucagon-Expressing Cells and Insulinoma Development. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 1954–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K.; Polonsky, K.S. Pdx1 and Other Factors That Regulate Pancreatic Β-cell Survival. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2009, 11, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ikeda, Y. PDX1, Neurogenin-3, and MAFA: Critical Transcription Regulators for Beta Cell Development and Regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granlund, L.; Korsgren, O.; Skog, O.; Lundberg, M. Extra-Islet Cells Expressing Insulin or Glucagon in the Pancreas of Young Organ Donors. Acta Diabetol. 2024, 61, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, S.A.; Ariel, I.; Thornton, P.S.; Scheimberg, I.; Glaser, B. Beta-Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis in the Developing Normal Human Pancreas and in Hyperinsulinism of Infancy. Diabetes 2000, 49, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case No. | Sex | Age of Onset | Age at Surgery, Month | Genetics | Minimal Glucose Level mmol/L | Maximal Insulin Level at the Time of Hypoglycemia, μU/mL | Treatment, Maximum Doses Used (Assessed Retrospectively) | PET 18F-DOPA Scan Results | Histological Form of CHI, Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 2nd day of life | 12 | Heterozygous paternal R1436G in ABCC8 | 1.2 | 18.0 | Diazoxide 7 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 30 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Focal uptake | Focal CHI, unaltered pancreatic islets Focal CHI, focus |

| 2 | M | 3rd day of life | 22 | c.A680G:p.E227G heterozygous paternal in KCNJ11 | 1.4 | 15.2 | Diazoxide 20 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 34 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Focal uptake | Focal CHI, unaltered pancreatic islets Focal CHI, focus |

| 3 | F | 1st day of life | 7 | R705X heterozygous paternal in ABCC8 | 1.8 | 38.0 | Diazoxide 16 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 20 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Focal uptake | Focal CHI, unaltered pancreatic islets Focal CHI, focus |

| 4 | F | 2nd day of life | 5 | c.G1332T: p.Q444H heterozygous paternal in ABCC8 | 0.7 | 45.0 | Diazoxide 5.5 mg/kg/day—discontinued due to side effects, Octreotide 20 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Focal uptake | Focal CHI, unaltered pancreatic islets Focal CHI, focus |

| 5 | M | 1st day of life | 5 | c 3330-13G>A heterozygous paternal in ABCC8 | 0.8 | 3.24 | Diazoxide 10.3 mg/kg/day with no improvement | Focal uptake | Focal CHI |

| 6 | F | 1st day of life | 7 | c.1037C>T:p.A346V homozygous in KCNJ11 | 0.2 | 6.5 | Diazoxide 11.9 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 10 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Focal uptake | Diffuse CHI |

| 7 | F | 1st day of life | 3 | C87R homozygous in KCNJ11 | 1.0 | 32.0 | Diazoxide 16 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 33 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Diffuse uptake | Diffuse CHI |

| 8 | F | 13 months | 19 | c.1361 1363dupCGG heterozygous in GCK | 0.6 | 28.0 | Diazoxide 18 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 20 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Diffuse uptake | Diffuse CHI |

| 9 | F | 1st day of life | 26 | Q444H/R1250X compound heterozygous in ABCC8 | 1.9 | 50.0 | Diazoxide 15 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 20 mcg/kg/day with no improvement | Diffuse uptake | Diffuse CHI |

| 10 | F | 1st day of life | 2 | c.405dupG:p.R136 AfsX 5 homozygous in KCNJ11 | 1.1 | 9.3 | Diazoxide 16 mg/kg/day, Octreotide 10 mcg/kg/day + continuous dextrose infusion 8.8 mg/kg/min with no improvement | Diffuse uptake | Diffuse CHI |

| 11 | F | 1st day of life | 2 | c.C387T:p.A129A heterozygous in HNF4A | 0.1 | 24 | High volume infusion, dextrose requirement rate 22.5 mg/kg/min, Diazoxide was contraindicated, Octreotide maximum dose 11.25 mg/kg/min, Glucagon infusion with no improvement, severe hypoglycemia and high infusion rate prompted surgical treatment | Diffuse uptake | Diffuse CHI |

| Antibodies | Company | Cat.#/RRID | Dilutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse monoclonal antibodies to insulin, clone INS04; INS05 | Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Fremont, CA, USA | MS-1379-P/ RRID:AB_62834 | 1:100 |

| Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to glucagon | Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Regensburg, Germany | PA5-13442/ RRID:AB_2107206 | 1:50 |

| Mouse monoclonal antibodies to glucagon, clone K79bB10 | Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA | G2654/ RRID:AB_259852 | 1:4000 |

| Rabbit monoclonal antibodies to PDX1, clone EP-139 | Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA | AC-0131C | 1:100 |

| IFluor™594 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG | Huabio, Hangzhou, China | HA1126 | 1:500 |

| IFluor™488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Huabio, Hangzhou, China | HA1121 | 1:500 |

| IFluor™488 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG | Huabio, Hangzhou, China | HA1125 | 1:500 |

| IFluor™594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Huabio, Hangzhou, China | HA1122 | 1:500 |

| Parameter | Focal CHI, Unaltered Pancreatic Islets | Focal CHI, Focus | Diffuse CHI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Islet area, μm2 | 9328.14 (5578.41–12,798.92) (n = 40) | 36,727.73 * (23,276.46–55,095.92) (n = 50) | 15,661.71 * (12,302.61–22,310.03) (n = 60) |

| Cell density (the no. of DAPI-positive nuclei per μm2 of islet area) | 0.016 (0.013–0.019) (n = 40) | 0.013 * (0.011–0.014) (n = 50) | 0.011 * (0.010–0.012) (n = 60) |

| Proportion of insulin+ cells of total cell no. (%) | 41.37 (34.22–47.82) (n = 40) | 50.83 * (41.86–57.59) (n = 50) | 34.09 * (28.57–39.64) (n = 60) |

| Proportion of glucagon+ cells of total cell no. (%) | 24.94 (20.05–30.39) (n = 40) | 8.07 * (5.60–12.65) (n = 50) | 21.65 (16.07–28.32) (n = 60) |

| Proportion of insulin+/glucagon+ cells of total cell no. (%) | 1.68 (0.58–2.97) (n = 40) | 1.52 (0.83–4.69) (n = 50) | 2.55 * (1.60–5.83) (n = 60) |

| Proportion of insulin+/glucagon+ cells of total no. of insulin+ cells (%) | 3.86 (1.60–6. 85) | 3.00 (1.67–7.69) | 6.61 (3.30–17.48) * |

| Proportion of insulin+/PDX1+ cells of total no. of insulin+ cells (%) | 89.90 (84.01–93.41) (n = 44) | 78.46 * (66.43–91.30) (n = 50) | 82.34 * (73.08–87.85) (n = 60) |

| Proportion of insulin+/PDX1− cells of total no. of insulin+ cells (%) | 10.10 (6.59–15.99) (n = 44) | 21.54 * (8.70–33.57) (n = 50) | 17.66 * (12.15–26.92) (n = 60) |

| Proportion of glucagon+/PDX1+ cells of total no. of glucagon+ cells (%) | 10.87 (4.26–15.56) (n = 47) | 9.41 (4.92–26.19) (n = 50) | 10.75 (6.38–16.98) (n = 63) |

| Proportion of glucagon+/PDX1− cells of total no. of glucagon+ cells (%) | 89.13 (84.44–95.74) (n = 47) | 90.59 (73.81–95.08) (n = 50) | 89.25 (83.02–93.62) (n = 63) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Krivova, Y.; Proshchina, A.; Otlyga, D.; Gubaeva, D.; Melikyan, M.; Saveliev, S. Cells Co-Producing Insulin and Glucagon in Congenital Hyperinsulinism. Life 2026, 16, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010018

Krivova Y, Proshchina A, Otlyga D, Gubaeva D, Melikyan M, Saveliev S. Cells Co-Producing Insulin and Glucagon in Congenital Hyperinsulinism. Life. 2026; 16(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrivova, Yuliya, Alexandra Proshchina, Dmitry Otlyga, Diliara Gubaeva, Maria Melikyan, and Sergey Saveliev. 2026. "Cells Co-Producing Insulin and Glucagon in Congenital Hyperinsulinism" Life 16, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010018

APA StyleKrivova, Y., Proshchina, A., Otlyga, D., Gubaeva, D., Melikyan, M., & Saveliev, S. (2026). Cells Co-Producing Insulin and Glucagon in Congenital Hyperinsulinism. Life, 16(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010018