The current proof-of-concept study provides novel insight into the potential diagnostic utility of AF-related clinical scores—traditionally used for predicting thromboembolic or rhythm outcomes—in stratifying the severity of CAD in patients with CCS. Among the risk scores evaluated, HAS-BLED and C2HEST emerged as independent predictors of significant coronary stenosis, and both demonstrated a statistically significant association with Gensini and SYNTAX scores, validated measures of angiographic CAD burden. These findings support the hypothesis that overlapping pathophysiological substrates between AF and CAD may be captured by multipurpose clinical scores, extending their utility beyond their original scope.

4.2. CHA2DS2VA and CHA2DS2VA-HSF: Beyond Stroke Risk

The CHA2DS2VA score, the new variant of the well-established CHA2DS2VASc score, was initially designed to assess thromboembolic risk in patients with AF. However, it incorporates clinical variables such as age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and vascular disease—all of which are independently associated with CAD. In our study, this score showed a significant association with the severity of angiographically confirmed CAD, suggesting its potential utility in broader cardiovascular risk stratification beyond AF populations.

Several prior studies have echoed these findings. For instance, Modi et al. investigated a modified version of the score, termed CHA

2DS

2VASc-HSF, which includes additional risk factors—hyperlipidemia, smoking, and family history of premature CAD. Their study of 2976 patients undergoing coronary angiography demonstrated that the CHA

2DS

2VASc-HSF score had a strong positive correlation with both the presence and severity of CAD, with a statistically significant association (

p < 0.001). This variant improved the ability to predict significant coronary lesions, underscoring the relevance of incorporating lifestyle and genetic predispositions in cardiovascular risk tools [

16].

Moreover, a study by Cetin et al. demonstrated that the CHA

2DS

2VASc score positively correlates with the severity and complexity of CAD in patients undergoing coronary angiography. They found that higher CHA

2DS

2VASc scores were associated with increased SYNTAX scores, indicating more complex coronary lesions [

17]. Furthermore, a study by Tran et al. introduced the CHA

2DS

2VASc-HS score, which adds hyperlipidemia and smoking to the original CHA

2DS

2VASc components. Their findings revealed a strong correlation between higher CHA

2DS

2VASc-HS scores and increased Gensini scores, suggesting that this modified score may be a useful tool for predicting CAD severity [

18].

In summary, our findings, supported by the existing literature, indicate that both the CHA2DS2VA and CHA2DS2VA-HSF scores, though originally developed for stroke risk in AF management, have broader applicability in assessing CAD severity. These scores, based on readily available clinical parameters, could serve as valuable tools in the early identification and risk stratification of patients with significant CAD.

4.3. HAS-BLED Score: A Marker for CAD Risk?

The HAS-BLED score, originally developed to estimate the risk of major bleeding in patients with AF undergoing anticoagulation therapy, includes clinical parameters such as hypertension, abnormal liver or renal function, stroke history, bleeding history, labile INR, age, and concomitant use of drugs or alcohol. While its primary application is in bleeding risk stratification, emerging evidence suggests that the HAS-BLED score may also reflect the overall burden of systemic vascular disease, thereby serving as a potential marker for CAD severity.

In our study, higher HAS-BLED scores were significantly associated with greater CAD severity, as assessed by the Gensini and SYNTAX scores. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that the components of the HAS-BLED score are closely linked to cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes. For instance, a study by Konishi et al. evaluated the predictive value of the HAS-BLED score in patients undergoing PCI with drug-eluting stents. The study found that a high HAS-BLED score (≥3) was independently associated with increased risks of major bleeding and all-cause mortality over a median follow-up of 3.6 years, regardless of the presence of AF. This suggests that the HAS-BLED score captures comorbidities and clinical features that contribute to both bleeding and ischemic risks [

19].

Similarly, Castini et al. investigated the utility of the HAS-BLED score for risk stratification in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) without AF. Their study demonstrated that higher HAS-BLED scores were associated with increased in-hospital and post-discharge bleeding events, as well as higher mortality rates. The discriminative performance of the HAS-BLED score for predicting these outcomes was moderate to good, indicating its potential applicability beyond bleeding risk assessment in AF patients [

20].

Further evidence supporting the utility of the HAS-BLED score in the stable CAD population is provided by Yildirim et al., who evaluated its performance in predicting hemorrhagic events in patients with chronic CAD receiving antithrombotic therapy. Although the primary focus was on bleeding risk, their findings underscore the applicability of HAS-BLED in this clinical context, demonstrating that it outperformed the CRUSADE score in forecasting major bleeding complications. This is particularly relevant, as many of the components included in HAS-BLED—such as hypertension, renal dysfunction, and prior stroke—are also well-established contributors to CAD progression and adverse outcomes. The study’s emphasis on stable CAD patients highlights that HAS-BLED may not only serve as a bleeding risk tool in anticoagulated populations, but also offer insight into the overall clinical complexity and frailty of CAD patients, further supporting its broader relevance in cardiovascular risk assessment [

21].

Taken together, these data support the concept that the HAS-BLED score—though originally designed for assessing bleeding risk in anticoagulated AF patients—may reflect broader vascular risk, including the presence and severity of CAD. Its components overlap substantially with known predictors of adverse cardiovascular events. Therefore, in the setting of CCS, particularly in patients with AF or multiple comorbidities, the HAS-BLED score may serve as a pragmatic and clinically valuable tool not only for anticipating bleeding risk but also for identifying individuals with potentially advanced atherosclerotic disease.

4.4. C2HEST Score: Predicting More than AF

The C

2HEST score, originally developed to predict the risk of incident AF, comprises six clinical variables: coronary artery disease (CAD) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (1 point each), hypertension (1 point), elderly (age ≥ 75 years, 2 points), systolic heart failure (2 points), and thyroid disease (hyperthyroidism, 1 point). While its primary application has been in AF risk stratification, emerging evidence suggests that the C

2HEST score may also serve as a marker for broader cardiovascular risk, including the severity of CAD [

22].

In our study, higher C

2HEST scores were significantly associated with greater CAD severity, as assessed by the Gensini and SYNTAX scores. This finding aligns with the components of the C

2HEST score, many of which are established risk factors for atherosclerosis and CAD progression. Supporting this, a study by Li et al. demonstrated that the C

2HEST score effectively predicted incident AF in a large cohort of post-ischemic stroke patients, with a C-index of 0.734, outperforming other risk scores such as the CHA

2DS

2VASc and Framingham risk scores. Although this study focused on AF prediction, the strong performance of the C

2HEST score underscores its potential utility in assessing overall cardiovascular risk [

22].

Moreover, a study by Rola et al. evaluated the utility of the C

2HEST score in predicting clinical outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without CAD. The study found that higher C

2HEST scores were associated with increased in-hospital, 3-month, and 6-month mortality rates, particularly in the CAD cohort. Specifically, in the CAD group, in-hospital mortality reached 43.06% in the high-risk C

2HEST stratum, compared to 26.92% in the non-CAD group. These findings suggest that the C

2HEST score captures comorbidities and clinical features that contribute to both bleeding and ischemic risks, extending its utility beyond AF prediction to broader cardiovascular risk assessment [

23].

These findings collectively indicate that the C2HEST score, although originally intended for AF prediction, captures a cluster of clinical features that overlap substantially with the risk profile of patients prone to significant CAD. In our cohort, patients with S-CCS exhibited significantly higher C2HEST scores compared to those with non-significant lesions, suggesting that this score may serve as a pragmatic tool for early recognition of more advanced coronary atherosclerosis. As such, the C2HEST score could offer additional diagnostic value in identifying individuals at higher risk of severe coronary stenosis, guiding in the selection of patients for invasive coronary angiography.

4.5. Clinical Implications, Study Limitations, and Future Directions

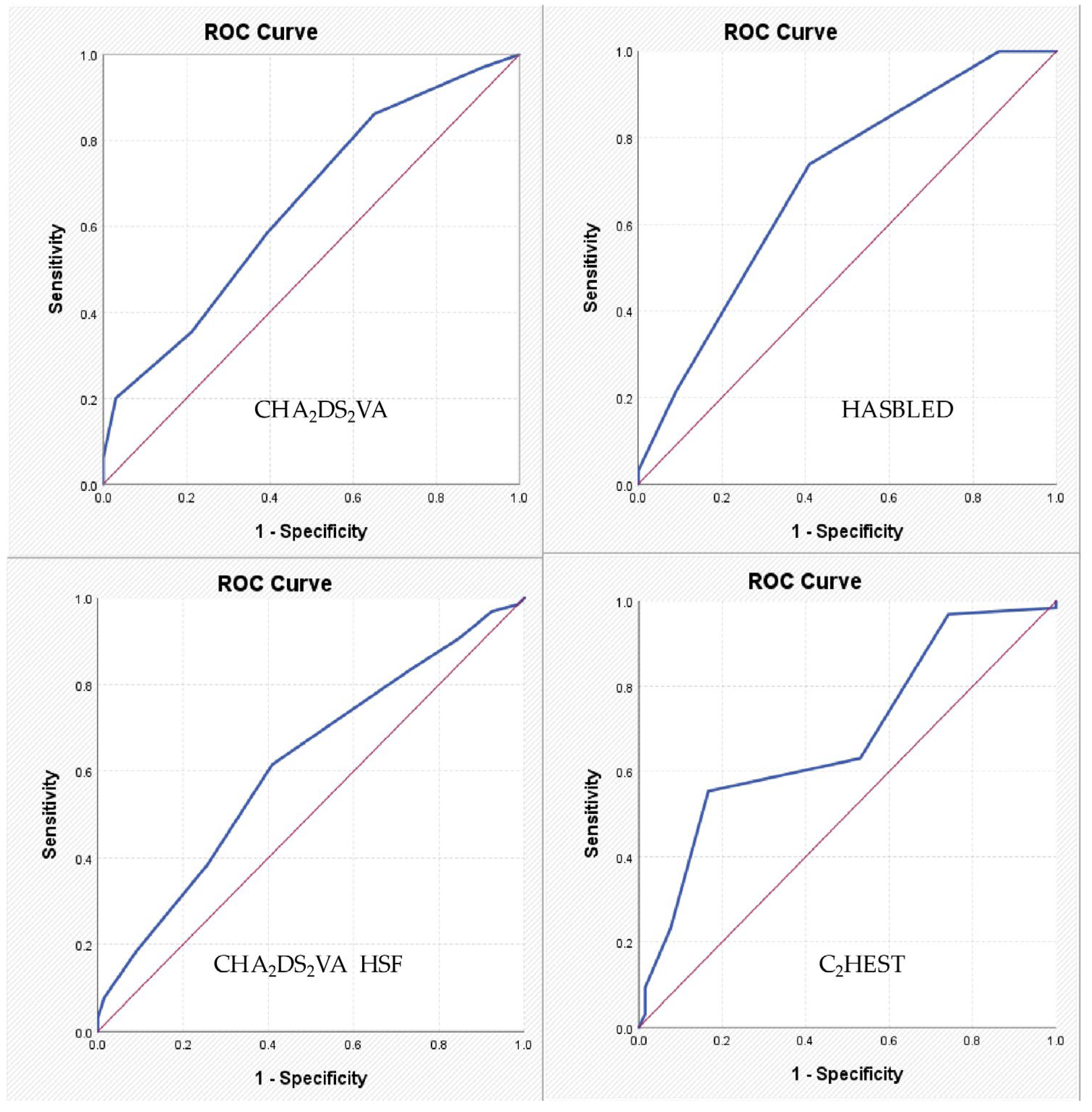

The potential repurposing of AF-related clinical scores such as CHA2DS2VA, CHA2DS2VA-HSF, HAS-BLED, and C2HEST for evaluating the severity of CAD introduces a pragmatic and accessible strategy for early cardiovascular risk stratification. These scores, based on widely available clinical parameters—such as age, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and prior vascular disease—offer low-cost, easy-to-use tools that can support decision-making in routine clinical practice. However, given their modest discriminative power (AUCs < 0.70), these scores should be considered as adjunctive rather than definitive tools, and their role is more suitable for preliminary triage rather than diagnostic confirmation.

A practical implication of our findings lies in the potential use of AF-related scores as a rapid, non-invasive screening tool in patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of CAD. In emergency or outpatient settings where immediate access to advanced imaging is limited, clinical scores like HAS-BLED or C2HEST could help identify high-risk patients who warrant early referral for invasive coronary assessment. Their simplicity and reliance on routinely collected clinical parameters allow for immediate bedside application without the need for additional laboratory or imaging data. This could streamline diagnostic pathways, reduce unnecessary testing, and optimize resource allocation.

Compared to traditional CAD risk estimation tools such as the Framingham risk score, ASCVD risk calculator, or the SCORE system—which rely primarily on lipid levels, smoking status, and long-term event prediction—AF-derived scores offer a distinct perspective focused on the cumulative burden of systemic comorbidities. While conventional models remain essential for long-term cardiovascular risk stratification in the general population, they may be less informative in acute or atypical presentations, particularly in patients with AF, where arrhythmia-related factors may obscure ischemic symptoms. In contrast, AF-related scores such as HAS-BLED and C2HEST capture overlapping clinical variables—age, hypertension, heart failure, and vascular disease—that may indirectly reflect coronary disease burden. Nevertheless, their diagnostic accuracy remains modest, and these scores should be viewed as complementary triage tools rather than replacements for established risk models or diagnostic imaging. Future studies should evaluate whether integrating AF-derived and traditional CAD scores could improve diagnostic precision in selected patient subsets.

It is also important to consider whether the performance of these repurposed scores may vary across different subgroups, such as sex, ethnicity, or comorbidity profiles. For instance, younger patients with non-valvular AF or those without overt cardiovascular symptoms may have deceptively low scores despite harboring significant coronary lesions. Similarly, sex-specific pathophysiological mechanisms could affect score sensitivity, given that women often present with atypical symptoms and microvascular disease. Although our study did not include stratified analyses, these factors should be addressed in future multicenter trials to refine risk-stratification tools across diverse populations.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, it was conducted in a single tertiary center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Differences in patient demographics, clinical practice patterns, and resource availability across institutions could influence the performance and applicability of these clinical scores in other settings. Second, the sample size—although adequate for a proof-of-concept analysis—was relatively modest (n = 131), potentially limiting the statistical power to detect subtle or borderline significant associations. Third, the severity of coronary stenoses was assessed primarily through visual estimation by experienced operators; although common in clinical practice, this approach is inherently subject to interobserver variability. Fourth, while AF-derived scores demonstrated statistically significant associations with CAD severity, they were not specifically developed for this purpose. Their predictive accuracy in detecting coronary atherosclerosis is inherently constrained by their original design, focused on rhythm and bleeding risk. Consequently, these scores should be viewed as adjunctive, hypothesis-generating tools that may support—but not replace—established diagnostic modalities such as coronary CT angiography or invasive coronary angiography. Finally, the study did not include longitudinal follow-up or clinical outcome tracking, precluding any conclusions regarding prognostic endpoints such as myocardial infarction, revascularization, hospital readmissions, or cardiovascular mortality (MACE).

Future research should focus on validating these findings in larger, multicenter populations, with stratification by age, sex, and clinical presentation. Additionally, developing hybrid risk models that combine clinical scores with imaging and biomarker data may enhance diagnostic precision and risk stratification in patients with suspected CAD.