Inter-Individual Heterogeneity in Aerobic Training Adaptations: Systematic Review of the Evidence Base for Personalized Exercise Prescription

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Literature Search and Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Quantifying Inter-Individual Differences in Training Response

2.5.2. Meta-Analytic Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Methods for Quantifying Aerobic Exercise Adaptation Heterogeneity and Classification of Individual Responses

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.4. Studies Estimating Interindividual Differences in Response to Aerobic Training

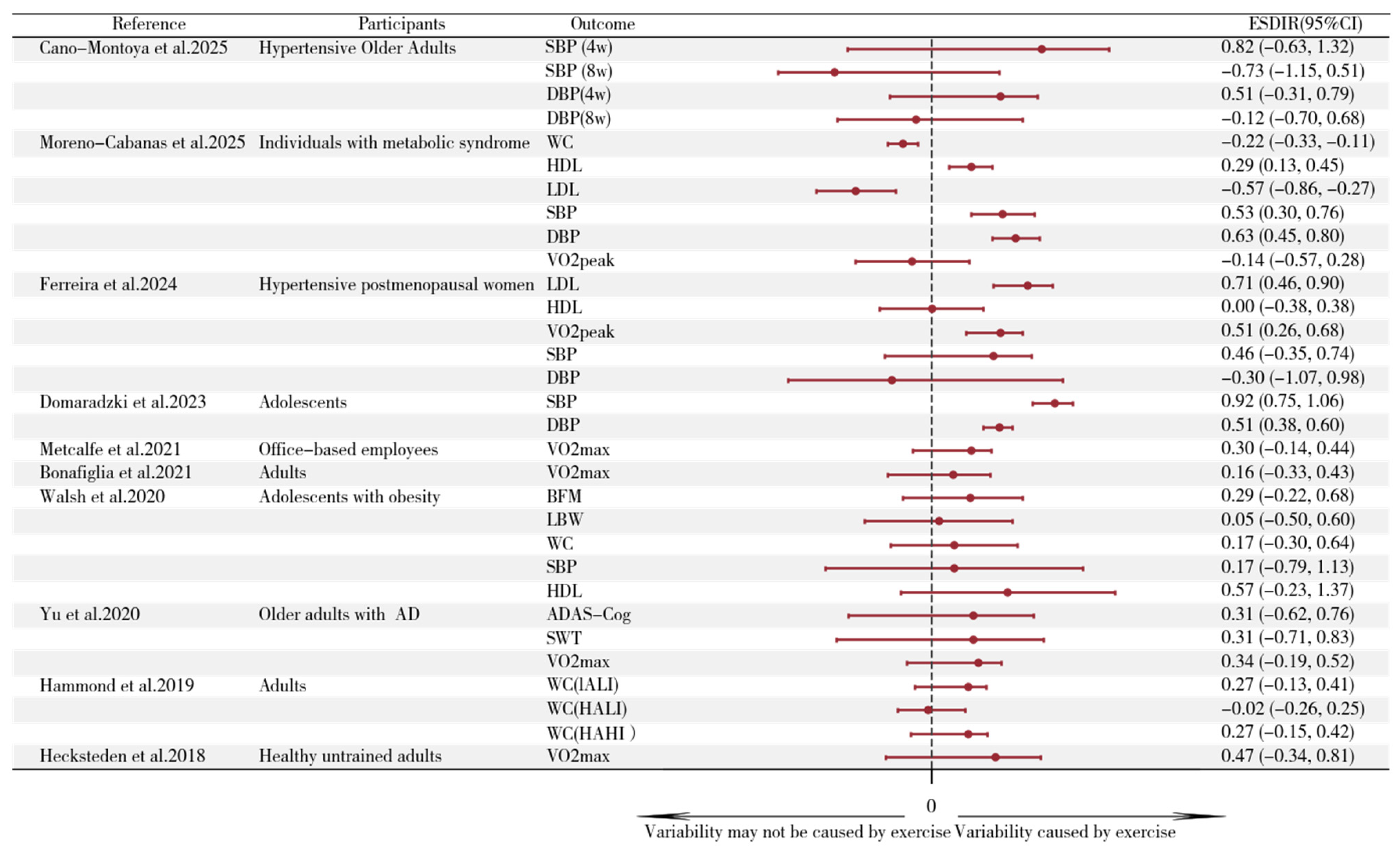

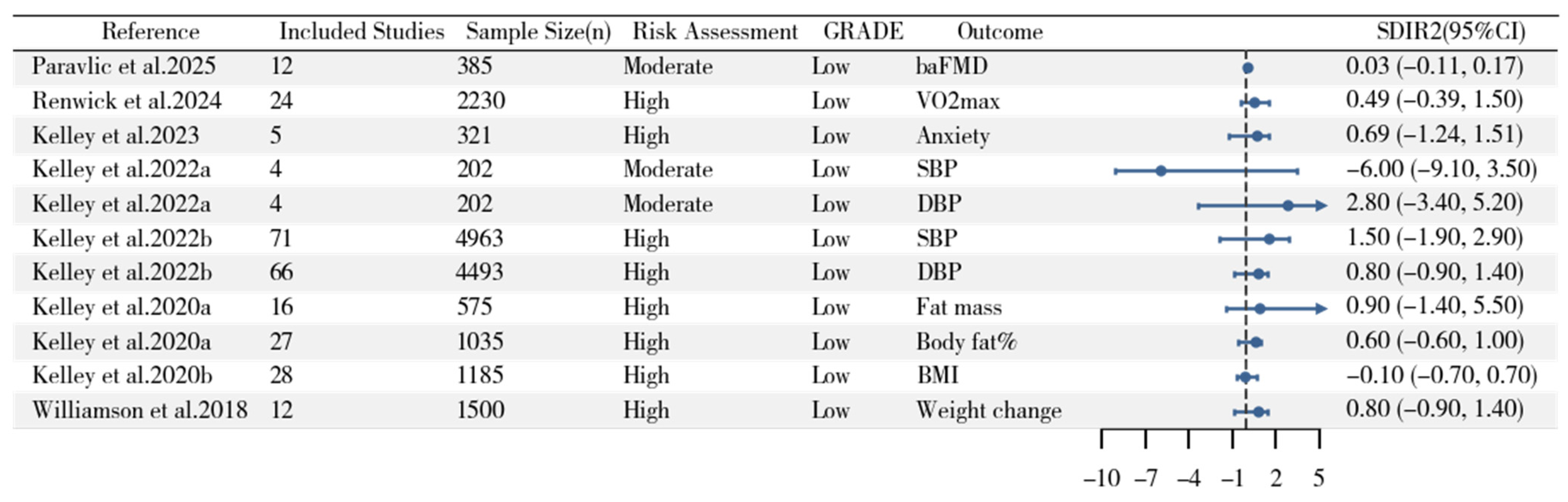

3.5. Separate Group Meta-Analysis on Standard Deviation of Change Scores

3.6. Standard Deviation of Individual Response

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength of the Study and Summary of Findings

4.2. Do No Inter-Individual Differences Exist in Exercise Intervention Effects?

4.3. Implications for Personalized Exercise Prescription

4.4. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Standard Deviation of Change Scores

Appendix A.2. Inter-Individual Differences in Adaptation

References

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Brit. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neufer, P.D.; Bamman, M.M.; Muoio, D.M.; Bouchard, C.; Cooper, D.M.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Booth, F.W.; Kohrt, W.M.; Gerszten, R.E.; Mattson, M.P.; et al. Understanding the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Physical Activity-Induced Health Benefits. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, B.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavirta, L.; Hakkinen, K.; Kauhanen, A.; Arija-Blazquez, A.; Sillanpaa, E.; Rinkinen, N.; Hakkinen, A. Individual responses to combined endurance and strength training in older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Cano-Montoya, J.; Ramirez-Velez, R.; Harridge, S.D.R.; Alonso-Martinez, A.M.; Izquierdo, M. Exercise and glucose control in children with insulin resistance: Prevalence of non-responders. Pediatr. Obes. 2018, 13, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Cristi-Montero, C.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Izquierdo, M. Prevalence of non-responders for blood pressure and cardiometabolic risk factors among prehypertensive women after long-term high-intensity interval training. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, D.; Lundby, C. Refuting the myth of non-response to exercise training: ‘non-responders’ do respond to higher dose of training. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3377–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. Individual responses made easy. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 118, 1444–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G.; Batterham, A.M. True and false interindividual differences in the physiological response to an intervention. Exp. Physiol. 2015, 100, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, J.R.M.; Preobrazenski, N.; Wu, Z.; Khansari, A.; LeBouedec, M.A.; Nuttall, J.M.G.; Bancroft, K.R.; Simpson-Stairs, N.; Swinton, P.A.; Gurd, B.J. Standard Deviation of Individual Response for VO2max Following Exercise Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 3069–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paravlic, A.H.; Drole, K. Effects of aerobic training on brachial artery flow-mediated dilation in healthy adults: A meta-analysis of inter-individual response differences in randomized controlled trials. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonafiglia, J.T.; Brennan, A.M.; Ross, R.; Gurd, B.J. An appraisal of the SDIR as an estimate of true individual differences in training responsiveness in parallel-arm exercise randomized controlled trials. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ-Brit. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafiglia, J.T.; Preobrazenski, N.; Gurd, B.J. A Systematic Review Examining the Approaches Used to Estimate Interindividual Differences in Trainability and Classify Individual Responses to Exercise Training. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 665044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ-Brit. Med. J. 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinton, P.A.; Hemingway, B.S.; Saunders, B.; Gualano, B.; Dolan, E. A Statistical Framework to Interpret Individual Response to Intervention: Paving the Way for Personalized Nutrition and Exercise Prescription. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecksteden, A.; Pitsch, W.; Rosenberger, F.; Meyer, T. Repeated testing for the assessment of individual response to exercise training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 124, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, S.A.R.; Barendregt, J.J.; Khan, S.; Thalib, L.; Williams, G.M. Advances in the meta-analysis of heterogeneous clinical trials I: The inverse variance heterogeneity model. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 45, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifer, E.S.; Mikus, C.R.; Karavirta, L.; Resnick, B.D.; Kraus, W.E.; Hakkinen, K.; Earnest, C.P.; Fleg, J.L. Adverse Cardiovascular Response to Aerobic Exercise Training: Is This a Concern? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, P.J.; Atkinson, G.; Batterham, A.M. Inter-Individual Responses of Maximal Oxygen Uptake to Exercise Training: A Critical Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1501–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonafiglia, J.T.; Ross, R.; Gurd, B.J. The application of repeated testing and monoexponential regressions to classify individual cardiorespiratory fitness responses to exercise training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, B.P.; Stotz, P.J.; Brennan, A.M.; Lamarche, B.; Day, A.G.; Ross, R. Individual Variability in Waist Circumference and Body Weight in Response to Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.J.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Goldfield, G.S.; Sigal, R.J.; Kenny, G.P.; Doucette, S.; Hadjiyannakis, S.; Alberga, A.S.; Prud’Homme, D.; Gurd, B.J. Interindividual variability and individual responses to exercise training in adolescents with obesity. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Salisbury, D.; Mathiason, M.A. Inter-individual differences in the responses to aerobic exercise in Alzheimer’s disease: Findings from the FIT-AD trial. J. Sports Health Sci. 2021, 10, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni Maturana, F.; Soares, R.N.; Murias, J.M.; Schellhorn, P.; Erz, G.; Burgstahler, C.; Widmann, M.; Munz, B.; Thiel, A.; Nieß, A.M. Responders and non-responders to aerobic exercise training: Beyond the evaluation of O2max. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea Schlagheck, M.; Wucherer, A.; Rademacher, A.; Joisten, N.; Proschinger, S.; Walzik, D.; Bloch, W.; Kool, J.; Gonzenbach, R.; Bansi, J.; et al. VO2peak Response Heterogeneity in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: To HIIT or Not to HIIT? Int. J. Sports Med. 2021, 42, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafiglia, J.T.; Islam, H.; Preobrazenski, N.; Ma, A.; Deschenes, M.; Erlich, A.T.; Quadrilatero, J.; Hood, D.A.; Gurd, B.J. Examining interindividual differences in select muscle and whole-body adaptations to continuous endurance training. Exp. Physiol. 2021, 106, 2168–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, J. Minimal Detectable Change in Resting Blood Pressure and Cardiorespiratory Fitness: A Secondary Analysis of a Study on School-Based High-Intensity Interval Training Intervention. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, J.; Kozlenia, D. Cardiovascular and cardiorespiratory effects of high-intensity interval training in body fat responders and non-responders. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Montoya, J.; Hurtado, N.; Núñez Vergara, C.; Báez Vargas, S.; Rojas-Vargas, M.; Martínez-Huenchullán, S.; Alvarez, C.; Izquierdo, M. Interindividual Variability Response to Resistance and High-Intensity Interval Training on Blood Pressure Reduction in Hypertensive Older Adults. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Cabañas, A.; Morales-Palomo, F.; Alvarez-Jimenez, L.; Mora-Gonzalez, D.; Garcia-Camacho, E.; Martinez-Mulero, B.; Mora-Rodriguez, R. Clinical and physiological effects of high-intensity aerobic training on metabolic syndrome: Understanding the individual exercise response variability. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 138, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, R.S.; Vollaard, N. Heterogeneity and incidence of non-response for changes in cardiorespiratory fitness following time-efficient sprint interval exercise training. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 46, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittlbock, M.; Heinzl, H. A simulation study comparing properties of heterogeneity measures in meta-analyses. Stat. Med. 2006, 25, 4321–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; White, I.R.; Riley, R.D. Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Stat. Med. 2012, 31, 3805–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Castro, A.; Nunes, S.; Dos Santos, M.; Cavaglieri, C.R.; Tanaka, H.; Chacon-Mikahil, M. Hypotensive effects of exercise training: Are postmenopausal women with hypertension non-responders or responders? Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 2172–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley A, G.A.; Kelley, K.S.; Stauffer, B.L. Inter-individual response differences on resting blood pressure as a result of qigong in adults: An ancillary meta-analysis of randomized trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S.; Stauffer, B.L. Walking and resting blood pressure: An inter-individual response difference meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S.; Callahan, L.F. Are There Interindividual Differences in Anxiety as a Result of Aerobic Exercise Training in Adults With Fibromyalgia? An Ancillary Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab. 2022, 103, 1858–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S.; Pate, R.R. Are There Inter-Individual Differences in Fat Mass and Percent Body Fat as a Result of Aerobic Exercise Training in Overweight and Obese Children and Adolescents? A Meta-Analytic Perspective. Child. Obes. 2020, 16, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S.; Pate, R.R. Inter-individual differences in body mass index were not observed as a result of aerobic exercise in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 16, e12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, P.J.; Atkinson, G.; Batterham, A.M. Inter-individual differences in weight change following exercise interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noone, J.; Mucinski, J.M.; Delany, J.P.; Sparks, L.M.; Goodpaster, B.H. Understanding the variation in exercise responses to guide personalized physical activity prescriptions. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 702–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, C.G.R.; Lally, J.; Holloway, G.P.; Heigenhauser, G.J.F.; Bonen, A.; Spriet, L.L. Repeated transient mRNA bursts precede increases in transcriptional and mitochondrial proteins during training in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 4795–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Edgett, B.A.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Shulman, T.; Ma, A.; Quadrilatero, J.; Simpson, C.A.; Gurd, B.J. Repeatability of exercise-induced changes in mRNA expression and technical considerations for qPCR analysis in human skeletal muscle. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankel, S.J.; Bell, Z.W.; Spitz, R.W.; Wong, V.; Viana, R.B.; Chatakondi, R.N.; Buckner, S.L.; Jessee, M.B.; Mattocks, K.T.; Mouser, J.G.; et al. Assessing differential responders and mean changes in muscle size, strength, and the crossover effect to 2 distinct resistance training protocols. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Gurd, B.J. Exercise response variability: Random error or true differences in exercise response? Exp. Physiol. 2020, 105, 2022–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, G.C.; Andreozzi, F.; Sesti, G. Pharmacogenetics of type 2 diabetes mellitus, the route toward tailored medicine. Diabetes-Metab. Res. 2019, 35, e3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, A. Emerging insights of decoding the genetic blueprint, molecular mechanisms, and future horizons in precision medicine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Dis. 2025, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollastro, C.; Ziviello, C.; Costa, V.; Ciccodicola, A. Pharmacogenomics of Drug Response in Type 2 Diabetes: Toward the Definition of Tailored Therapies? PPAR Res. 2015, 2015, 415149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Donnelly, L.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Deshmukh, H.; Van Zuydam, N.; Ahlqvist, E.; Spencer, C.C.; Groop, L.; Morris, A.D.; et al. Heritability of variation in glycaemic response to metformin: A genome-wide complex trait analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatmal, M.M.; Abuyaman, O.; Al-Hatamleh, M.A.I.; Tayyem, H.; Olaimat, A.N.; Mussa, A.; Aolymat, I.; Abuawad, A.; Odeh, M.; Qawaqzeh, R. Influence of OCT2 gene variants on metformin efficacy in type 2 diabetes: Insights into pharmacogenomics and drug interactions. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.H.; Perry, J.A.; Jablonski, K.A.; Srinivasan, S.; Chen, L.; Todd, J.N.; Harden, M.; Mercader, J.M.; Pan, Q.; Dawed, A.Y.; et al. Identification of Genetic Variation Influencing Metformin Response in a Multiancestry Genome-Wide Association Study in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Diabetes 2023, 72, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, S.K.; Stewart, N.R. Metformin May Contribute to Inter-individual Variability for Glycemic Responses to Exercise. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, M.; Sharma, A.R.; Mallya, S.; Prabhu, N.B.; Jayaram, P.; Nagri, S.K.; Umakanth, S.; Rai, P.S. Implications of genetic variations, differential gene expression, and allele-specific expression on metformin response in drug-naive type 2 diabetes. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2023, 46, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, F.; Kallel, A.; Khessairi, N.; Yazidi, M.; Oueslati, I.; Chatti, H.A.; Feki, M.; Chihaoui, M. Metformin efficacy and tolerance according to genetic polymorphisms of organic cation transporter 1 in Tunisian patients with type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1536402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.C.; Mavros, Y.; Tajouri, L.; Singh, M.F. The Role of Genetic Profile in Functional Performance Adaptations to Exercise Training or Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 594–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, E.A.; Snoek, J.A.; Meindersma, E.P.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Bellersen, L.; Verbeek, A.L.M.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H. Absence of Fitness Improvement Is Associated with Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.; Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Izquierdo, M. Effects and prevalence of nonresponders after 12 weeks of high-intensity interval or resistance training in women with insulin resistance: A randomized trial. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.; Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Izquierdo, M. Effects of 6-Weeks High-Intensity Interval Training in Schoolchildren with Insulin Resistance: Influence of Biological Maturation on Metabolic, Body Composition, Cardiovascular and Performance Non-responses. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astorino, T.A.; DeRevere, J.; Anderson, T.; Kellogg, E.; Holstrom, P.; Ring, S.; Ghaseb, N. Change in VO2max and time trial performance in response to high-intensity interval training prescribed using ventilatory threshold. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 1811–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonafiglia, J.T.; Nelms, M.W.; Preobrazenski, N.; LeBlanc, C.; Robins, L.; Lu, S.; Lithopoulos, A.; Walsh, J.J.; Gurd, B.J. Moving beyond threshold-based dichotomous classification to improve the accuracy in classifying non-responders. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonafiglia, J.T.; Rotundo, M.P.; Whittall, J.P.; Scribbans, T.D.; Graham, R.B.; Gurd, B.J. Inter-Individual Variability in the Adaptive Responses to Endurance and Sprint Interval Training: A Randomized Crossover Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalleck, L.C.; Van Guilder, G.P.; Richardson, T.B.; Vella, C.A. The prevalence of adverse cardiometabolic responses to exercise training with evidence-based practice is low. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2015, 8, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lannoy, L.; Clarke, J.; Stotz, P.J.; Ross, R. Effects of intensity and amount of exercise on measures of insulin and glucose: Analysis of inter-individual variability. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Islam, H.; Preobrazenski, N.; Amato, A.; Gurd, B.J. Investigating the reproducibility of maximal oxygen uptake responses to high-intensity interval training. J. Sci. Med. Sports 2020, 23, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, J. The association between sperm telomere length, cardiorespiratory fitness and exercise training in humans. Biomed. J. 2019, 42, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgett, B.A.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Raleigh, J.P.; Rotundo, M.P.; Giles, M.D.; Whittall, J.P.; Gurd, B.J. Reproducibility of peak oxygen consumption and the impact of test variability on classification of individual training responses in young recreationally active adults. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2018, 38, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.R.; Aird, T.P.; Farquharson, A.J.; Horgan, G.W.; Fisher, E.; Wilson, J.; Hopkins, G.E.; Anderson, B.; Ahmad, S.A.; Davis, S.R.; et al. Inter-individual responses to sprint interval training, a pilot study investigating interactions with the sirtuin system. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurd, B.J.; Giles, M.D.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Raleigh, J.P.; Boyd, J.C.; Ma, J.K.; Zelt, J.G.E.; Scribbans, T.D. Incidence of nonresponse and individual patterns of response following sprint interval training. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, A.; Schmitt, L.; Troesch, S.; Saugy, J.J.; Cejuela-Anta, R.; Faiss, R.; Robinson, N.; Wehrlin, J.P.; Millet, G.P. Similar Hemoglobin Mass Response in Hypobaric and Normobaric Hypoxia in Athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Siemens, T.L.; Matusiak, J.B.L.; Sawula, L.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Preobrazenski, N.; Jung, M.E.; Gurd, B.J. Cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular endurance responses immediately and 2 months after a whole-body Tabata or vigorous-intensity continuous training intervention. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krusnauskas, R.; Eimantas, N.; Baranauskiene, N.; Venckunas, T.; Snieckus, A.; Brazaitis, M.; Westerblad, H.; Kamandulis, S. Response to Three Weeks of Sprint Interval Training Cannot Be Explained by the Exertional Level. Medicina 2020, 56, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leddy, A.L.; Connolly, M.; Holleran, C.L.; Hennessy, P.W.; Woodward, J.; Arena, R.A.; Roth, E.J.; Hornby, T.G. Alterations in Aerobic Exercise Performance and Gait Economy Following High-Intensity Dynamic Stepping Training in Persons With Subacute Stroke. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2016, 40, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonska-Duniec, A.; Jastrzebski, Z.; Jazdzewska, A.; Moska, W.; Lulinska-Kuklik, E.; Sawczuk, M.; Gubaydullina, S.I.; Shakirova, A.T.; Cieszczyk, P.; Maszczyk, A.; et al. Individual Responsiveness to Exercise-Induced Fat Loss and Improvement of Metabolic Profile in Young Women is Associated with Polymorphisms of Adrenergic Receptor Genes. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2018, 17, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Massie, R.; Smallcombe, J.; Tolfrey, K. Effects of a 12-Week Exercise Intervention on Subsequent Compensatory Behaviors in Adolescent Girls: An Exploratory Study. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 31, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, R.S.; Tardif, N.; Thompson, D.; Vollaard, N.B. Changes in aerobic capacity and glycaemic control in response to reduced-exertion high-intensity interval training (REHIT) are not different between sedentary men and women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raleigh, J.P.; Giles, M.D.; Islam, H.; Nelms, M.; Bentley, R.F.; Jones, J.H.; Neder, J.A.; Boonstra, K.; Quadrilatero, J.; Simpson, C.A.; et al. Contribution of central and peripheral adaptations to changes in maximal oxygen uptake following 4 weeks of sprint interval training. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raleigh, J.P.; Giles, M.D.; Scribbans, T.D.; Edgett, B.A.; Sawula, L.J.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Graham, R.B.; Gurd, B.J. The impact of work-matched interval training on O2peak and O2 kinetics: Diminishing returns with increasing intensity. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Hernández-Quiñones, P.A.; Tordecilla-Sanders, A.; Alvarez, C.; Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Izquierdo, M.; Correa-Bautista, J.E.; Garcia-Hermoso, A.; Garcia, R.G. Effectiveness of HIIT compared to moderate continuous training in improving vascular parameters in inactive adults. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; de Lannoy, L.; Stotz, P.J. Separate Effects of Intensity and Amount of Exercise on Interindividual Cardiorespiratory Fitness Response. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, B.J.; Bhammar, D.M.; Angadi, S.S.; Ryan, D.M.; Ryder, J.R.; Sussman, E.J.; Bertmann, F.M.; Gaesser, G.A. Predictors of fat mass changes in response to aerobic exercise training in women. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, M.M.; Palumbo, E.; Seay, R.F.; Spain, K.K.; Clarke, H.E. Energy compensation after sprint- and high-intensity interval training. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulhauser, K.T.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; McKie, G.L.; McCarthy, S.F.; Islam, H.; Townsend, L.K.; Grisebach, D.; Todd, C.; Gurd, B.J.; Hazell, T. Individual patterns of response to traditional and modified sprint interval training. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, N.A.; Brouwers, B.; Eroshkin, A.M.; Yi, F.; Cornnell, H.H.; Meyer, C.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Pratley, R.E.; Smith, S.R.; Sparks, L.M. Exercise Response Variations in Skeletal Muscle PCr Recovery Rate and Insulin Sensitivity Relate to Muscle Epigenomic Profiles in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellers, H.L.; Verhein, K.C.; Burkholder, A.B.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Lightfoot, J.T.; Shi, M.; Weinberg, C.R.; Sarzynski, M.A.; Bouchard, C.; et al. Association between Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variants and VO2max Trainability. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 2303–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Breneman, C.B.; Sparks, J.R.; Blair, S.N. Sedentary Time and Physical Activity in Older Women Undergoing Exercise Training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 2590–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherwax, R.M.; Harris, N.K.; Kilding, A.E.; Dalleck, L.C. Using a site-specific technical error to establish training responsiveness: A preliminary explorative study. Open Access J. Sports 2018, 9, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherwax, R.M.; Harris, N.K.; Kilding, A.E.; Dalleck, L.C. Incidence of V O2max Responders to Personalized versus Standardized Exercise Prescription. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherwax, R.M.; Ramos, J.S.; Harris, N.K.; Kilding, A.E.; Dalleck, L.C. Changes in Metabolic Syndrome Severity Following Individualized Versus Standardized Exercise Prescription: A Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.J.; Gurd, B.J.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Voisin, S.; Li, Z.; Harvey, N.; Croci, I.; Taylor, J.L.; Gajanand, T.; Ramos, J.S.; et al. A Multi-Center Comparison of VO2peak Trainability Between Interval Training and Moderate Intensity Continuous Training. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witvrouwen, I.; Pattyn, N.; Gevaert, A.B.; Possemiers, N.; Van Craenenbroeck, A.H.; Cornelissen, V.A.; Beckers, P.J.; Vanhees, L.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M. Predictors of response to exercise training in patients with coronary artery disease—A subanalysis of the SAINTEX-CAD study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 1158–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolpern, A.E.; Burgos, D.J.; Janot, J.M.; Dalleck, L.C. Is a threshold-based model a superior method to the relative percent concept for establishing individual exercise intensity? a randomized controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. R. 2015, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Eynon, N.; Papadimitriou, I.D.; Kuang, J.J.; Munson, F.; Tirosh, O.; O’Keefe, L.; Griffiths, L.R.; Ashton, K.J.; Byrne, N.; et al. The gene SMART study: Method, study design, and preliminary findings. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, B.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Yim, S.V. Genetic polymorphisms to predict gains in maximal O2 uptake and knee peak torque after a high intensity training program in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, J.P.; Hetherington-Rauth, M.; Júdice, P.B.; Correia, I.R.; Rosa, G.B.; Henriques-Neto, D.; Melo, X.; Silva, A.M.; Sardinha, L.B. Interindividual Variability in Fat Mass Response to a 1-Year Randomized Controlled Trial With Different Exercise Intensities in Type 2 Diabetes: Implications on Glycemic Control and Vascular Function. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 698971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Aravena, A.; Herrera-Valenzuela, T.; Valdés-Badilla, P.; Cancino-López, J.; Zapata-Bastias, J.; García-García, J.M. Inter-Individual Variability of a High-Intensity Interval Training With Specific Techniques vs. Repeated Sprints Program in Sport-Related Fitness of Taekwondo Athletes. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 766153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Mayorga, O.; Martínez-Maturana, N.; Salazar, L.A.; Díaz, E. Physiological Effects and Inter-Individual Variability to 12 Weeks of High Intensity-Interval Training and Dietary Energy Restriction in Overweight/Obese Adult Women. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 713016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubeniuk, T.J.; Bouchard, D.R.; Gurd, B.J.; Sénéchal, M. Can non-responders be ‘rescued’ by increasing exercise intensity? A quasi-experimental trial of individual responses among humans living with pre-diabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Potiaumpai, M.; Schmitz, K.; Sturgeon, K. Increased Duration of Exercise Decreases Rate of Nonresponse to Exercise but May Not Decrease Risk for Cancer Mortality. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, J.; Kozlenia, D.; Popowczak, M. The Prevalence of Responders and Non-Responders for Body Composition, Resting Blood Pressure, Musculoskeletal, and Cardiorespiratory Fitness after Ten Weeks of School-Based High-Intensity Interval Training in Adolescents. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, E.; Kleinhapl, J.; Suman-Vejas, O.E. Inter-individual variability of aerobic capacity after rehabilitation exercise training in children with severe burn injury. Burns 2024, 50, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltz, R.R.; Faricier, R.; Prior, P.L.; Hartley, T.; Huitema, A.A.; McKelvie, R.S.; Suskin, N.G.; Keir, D.A. A standardized approach to evaluate effectiveness of aerobic exercise training interventions in cardiovascular disease at the individual level. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 412, 132335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preobrazenski, N.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Nelms, M.W.; Lu, S.M.; Robins, L.; LeBlanc, C.; Gurd, B.J. Does blood lactate predict the chronic adaptive response to training: A comparison of traditional and talk test prescription methods. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinton, P.A. The influence of baseline capability on intervention effects in strength and conditioning: A review of concepts and methods with meta-analysis. SportRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistical Approach | Estimated Source of Variation | Interpretation/Use |

|---|---|---|

| TEM (TEM = SDdiff/) | Random measurement error (within-subject, test–retest). | Quantifies the “noise” from the measurement tool and day-to-day biological fluctuation. |

| Linear Mixed Effects Model: Fixed Factor: Training Group Random Factor: Participant Identity | Direct estimate of the subject-by-training interaction (true inter-individual response variance). | Determines each individual’s consistent, repeatable response to the training intervention by isolating it from random and within-subject variation. |

| SDIR = | Inter-individual response variance attributable to exercise (group-based), net of random and within-subject variation assuming equality across groups. | Preferred practical estimator in parallel-arm trials; relies on equal error structure between groups and sufficient sample size. |

| TEΔ (TEΔ = SDdiff/) | Estimate of within-subject variation (from a control group). | Estimates the “noise” (error) expected in change scores when no intervention is applied; used to set response thresholds or calculate confidence intervals. |

| SDIR = | Inter-individual response variance after removing random measurement error only; within-subject variation remains. | Approximate/upper-bound when a control group is unavailable; validity depends on transferability of reliability sample and prior trial duration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, H.; Ren, J. Inter-Individual Heterogeneity in Aerobic Training Adaptations: Systematic Review of the Evidence Base for Personalized Exercise Prescription. Life 2025, 15, 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121932

Xiao H, Ren J. Inter-Individual Heterogeneity in Aerobic Training Adaptations: Systematic Review of the Evidence Base for Personalized Exercise Prescription. Life. 2025; 15(12):1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121932

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Haili, and Jianchang Ren. 2025. "Inter-Individual Heterogeneity in Aerobic Training Adaptations: Systematic Review of the Evidence Base for Personalized Exercise Prescription" Life 15, no. 12: 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121932

APA StyleXiao, H., & Ren, J. (2025). Inter-Individual Heterogeneity in Aerobic Training Adaptations: Systematic Review of the Evidence Base for Personalized Exercise Prescription. Life, 15(12), 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121932