Associations Between PFAS Exposure and HPG Axis Hormones in U.S. Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Measurement of Serum PFAS Levels

2.3. Measurement of Serum Sex Hormone Levels

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMH | Anti-Müllerian hormone |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ETS | Environmental tobacco smoke |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating hormone |

| GFI | Goodness-of-fit index |

| HPG | Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LC–MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone |

| Ln | Natural log transformed |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| NFI | Normed fit index |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PFAS | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFHxS | Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid |

| PFNA | Perfluorononanoic acid |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid |

| n-PFOA | Linear perfluorooctanoic acid |

| RMR | Root mean square residual |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| SHBG | Sex hormone-binding globulin |

| StAR | Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein |

| SWAN | Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation |

References

- Gaines, L.G.T. Historical and current usage of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A literature review. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2023, 66, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, M.; Dunder, L.; Lind, P.M.; Lind, L.; Salihovic, S. Associations of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with lipid and lipoprotein profiles. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoso, E.; Masi, M.; Racchi, M.; Corsini, E. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals’ (EDCs) Effects on Tumour Microenvironment and Cancer Progression: Emerging Contribution of RACK1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bline, A.P.; DeWitt, J.C.; Kwiatkowski, C.F.; Pelch, K.E.; Reade, A.; Varshavsky, J.R. Public Health Risks of PFAS-Related Immunotoxicity Are Real. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, V.; Bil, W.; Vandebriel, R.; Granum, B.; Luijten, M.; Lindeman, B.; Grandjean, P.; Kaiser, A.-M.; Hauzenberger, I.; Hartmann, C.; et al. Consideration of pathways for immunotoxicity of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Health 2023, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basini, G.; Bussolati, S.; Torcianti, V.; Grasselli, F. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) affects steroidogenesis and antioxidant defence in granulosa cells from swine ovary. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 101, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-T.; Li, R.; Li, S.-H.; Ma, X.; Liu, L.; Niu, D.; Duan, X. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposure affects early embryonic development and offspring oocyte quality via inducing mitochondrial dysfunction. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Bai, Y.; Tang, C.; Cao, X.; Chang, F.; Chen, L. Impact of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate on Reproductive Ability of Female Mice through Suppression of Estrogen Receptor α-Activated Kisspeptin Neurons. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 165, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koysombat, K.; Dhillo, W.S.; Abbara, A. Assessing hypothalamic pituitary gonadal function in reproductive disorders. Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Alpadi, K.; Wang, L.; Li, R.; Qiao, J. Clinical Applications of Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone Measurements in Both Males and Females: An Update. Innovation 2021, 2, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.C.; Johns, L.E.; Meeker, J.D. Serum Biomarkers of Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Relation to Serum Testosterone and Measures of Thyroid Function among Adults and Adolescents from NHANES 2011–2012. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6098–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Aimuzi, R.; Nian, M.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, K.; Zhang, J. Perfluoroalkyl substances and sex hormones in postmenopausal women: NHANES 2013–2016. Environ. Int. 2021, 149, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Weng, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Gao, X.; Fei, Q.; Hao, G.; Jing, C.; Feng, L. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl substance exposure and association with sex hormone concentrations: Results from the NHANES 2015–2016. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.S.; Chen, C.; Thurston, S.W.; Haug, L.S.; Sabaredzovic, A.; Fjeldheim, F.N.; Frydenberg, H.; Lipson, S.F.; Ellison, P.T.; Thune, I. Perfluoroalkyl substances and ovarian hormone concentrations in naturally cycling women. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 1261–1270.e1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, S.D.; Hood, M.M.; Ding, N.; Mukherjee, B.; Calafat, A.M.; Randolph, J.F.; Gold, E.B.; Park, S.K. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Hormone Levels During the Menopausal Transition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4427–e4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.R. Interpretation of reproductive hormones before, during and after the pubertal transition-Identifying health and disordered puberty. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021, 95, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Kapoor, E.; Geske, J.R.; Fields, J.A.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Morrow, M.M.; Winham, S.J.; Faubion, L.L.; Castillo, A.M.; Hofrenning, E.I.; et al. Long-term effects of premenopausal bilateral oophorectomy with or without hysterectomy on physical aging and chronic medical conditions. Menopause 2023, 30, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. NHANES 2017–2018. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2017 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- CDC. Online Solid Phase Extraction-High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Turbo Ion Spray-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (Online SPE-HPLC-TIS-MS/MS). Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2017/labmethods/PFAS-J-MET-508.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- CDC. Sex Steroid Hormone Panel—Serum (Surplus). Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Data/Nhanes/Public/2017/DataFiles/SSTST_J.htm#Eligible_Sample (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Smoking. Available online: http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/DataPage.aspx?Component=Questionnaire&CycleBeginYear=2013 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- CDC. 2017–2018 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies: Physical Activity. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Data/Nhanes/Public/2017/DataFiles/PAQ_J.htm#Appendix_1.__Suggested_MET_Scores (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Lee, J.S.; Ettinger, B.; Stanczyk, F.Z.; Vittinghoff, E.; Hanes, V.; Cauley, J.A.; Chandler, W.; Settlage, J.; Beattie, M.S.; Folkerd, E.; et al. Comparison of methods to measure low serum estradiol levels in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 3791–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. NHANES Analytic Guidance and Brief Overview for the 2017-March 2020 Pre-Pandemic Data Files. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/overviewbrief.aspx?cycle=2017-2020 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Harlow, S.D.; Randolph, J.F., Jr.; Loch-Caruso, R.; Park, S.K. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and their effects on the ovary. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 724–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.S.; Choi, J.S.; Park, J.W. Transcriptional changes in steroidogenesis by perfluoroalkyl acids (PFOA and PFOS) regulate the synthesis of sex hormones in H295R cells. Chemosphere 2016, 155, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Ortega, A.; Betancourt, M.; Rosas, P.; Vázquez-Cuevas, F.G.; Chavira, R.; Bonilla, E.; Casas, E.; Ducolomb, Y. Endocrine disruptor effect of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) on porcine ovarian cell steroidogenesis. Toxicol. Vitr. 2018, 46, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, A.; Salazar, Z.; Arenas, E.; Betancourt, M.; Ducolomb, Y.; González-Márquez, H.; Casas, E.; Teteltitla, M.; Bonilla, E. Effect of perfluorooctane sulfonate on viability, maturation and gap junctional intercellular communication of porcine oocytes in vitro. Toxicol. Vitr. 2016, 35, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Cao, X.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, R.; Chen, L. Chronic Exposure of Female Mice to an Environmental Level of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Suppresses Estrogen Synthesis Through Reduced Histone H3K14 Acetylation of the StAR Promoter Leading to Deficits in Follicular Development and Ovulation. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 148, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voros, C.; Athanasiou, D.; Papapanagiotou, I.; Mavrogianni, D.; Varthaliti, A.; Bananis, K.; Athanasiou, A.; Athanasiou, A.; Papadimas, G.; Gkirgkinoudis, A.; et al. Molecular Shadows of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): Unveiling the Impact of Perfluoroalkyl Substances on Ovarian Function, Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS), and In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.L.; Shukla, M.; George, J.W.; Gustin, S.; Rowley, M.J.; Davis, J.S. An environmentally relevant mixture of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) impacts proliferation, steroid hormone synthesis, and gene transcription in primary human granulosa cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2024, 200, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, L.; De Rocco Ponce, M.; Petre, G.C.; Rtibi, K.; Di Nisio, A.; Foresta, C. Bisphenols and Male Reproductive Health: From Toxicological Models to Therapeutic Hypotheses. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mo, J.; Zhong, Y.; Ge, R.-S. Bisphenols and Leydig Cell Development and Function. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean/Numbers | SD/% |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 49.01 | 15.75 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Mexican-American | 90 | 14.7 |

| Other Hispanic | 55 | 9.0 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 232 | 37.9 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 124 | 20.3 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 79 | 12.9 |

| Other ethnicities | 32 | 5.2 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 104 | 17.0 |

| Environmental tobacco smoke | 102 | 16.7 |

| Non-smoker | 406 | 66.3 |

| Alcohol consumption ≥ 12 drinks/year | 396 | 64.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.88 | 8.86 |

| Physical activity (MET-hours/day) | 10.26 | 16.95 |

| Total (N = 612) | Premenopause (N = 337) | Postmenopause (N = 275) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Mean (95% CI) | Geometric Mean (95% CI) | Geometric Mean (95% CI) | |

| PFAS (ng/mL) | |||

| n-PFOA | 1.20 (1.07–1.33) | 1.01 (0.87–1.18) | 1.50 (1.35–1.66) |

| PFOS | 3.53 (3.18–3.93) | 2.68 (2.40–2.98) | 5.11 (4.36–5.98) |

| PFNA | 0.40 (0.33–0.48) | 0.32 (0.25–0.41) | 0.54 (0.45–0.65) |

| PFHxS | 0.82 (0.75–0.91) | 0.63 (0.53–0.74) | 1.18 (1.09–1.29) |

| Sex hormones | |||

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 16.27 (13.54–19.54) | 5.98 (4.86–7.35) | 61.03 (55.58–67.01) |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 0.17 (0.12–0.24) | 0.81 (0.53–1.24) | 0.02 (0.02–0.02) |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 21.48 (17.83–25.88) | 56.76 (47.10–68.40) | 5.95 (5.12–6.92) |

| Progesterone (ng/dL) | 11.97 (9.30–15.39) | 33.69 (25.48–44.55) | 3.00 (2.40–3.75) |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | AMH (ng/mL) | Estradiol (pg/mL) | Progesterone (ng/dL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS (ng/mL) | % Change per IQR (95% CI) | p Value | % Change per IQR (95% CI) | p Value | % Change per IQR (95% CI) | p Value | % Change per IQR (95% CI) | p Value |

| n-PFOA | 19.7 (3.2, 38.8) | 0.035 | −16.4 (−29.3, −1.3) | 0.048 | −23.2 (−37.4, −5.9) | 0.017 | −35.2 (−58.5, 1.0) | 0.068 |

| PFOS | 31.7 (5.2, 64.9) | 0.032 | −12.9 (−30.4, 9.1) | 0.236 | −29.9 (−41.5, −16.1) | 0.002 | −47.4 (−63.3, −24.6) | 0.003 |

| PFNA | 42.0 (11.1, 81.5) | 0.010 | −32.2 (−41.5, −21.4) | <0.001 | −33.0 (−46.3, −16.5) | 0.004 | −40.9 (−60.1, −12.5) | 0.021 |

| PFHxS | 21.6 (1.4, 45.8) | 0.057 | −4.0 (−18.3, 12.8) | 0.592 | −24.3 (−36.8, −9.2) | 0.007 | −37.1 (−57.1, −7.7) | 0.031 |

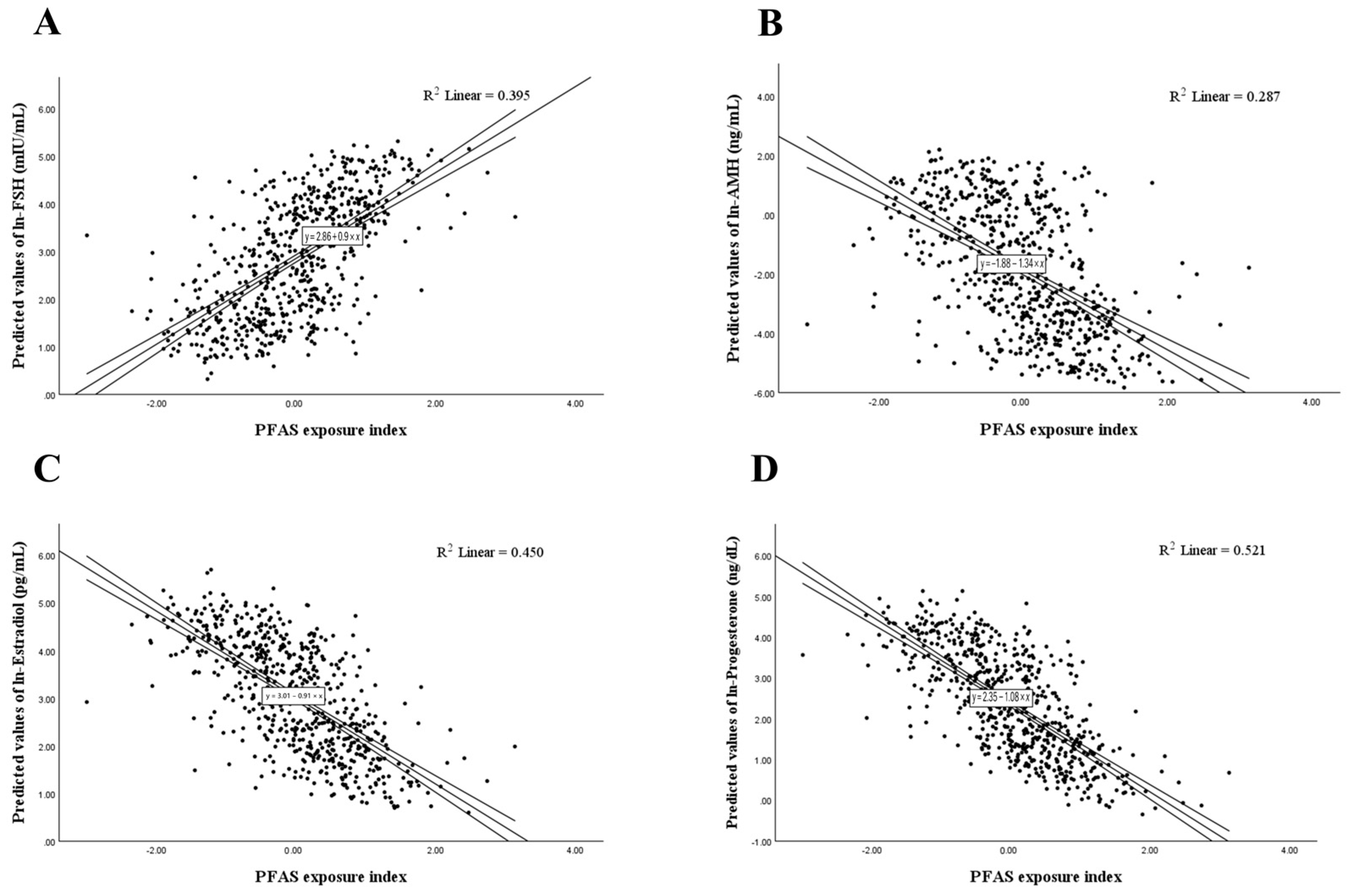

| PFAS Exposure Index * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change per IQR (95% CI) | p Value | p for Interaction | |||||

| Age | Ethnicity | BMI | Smoking | Drinking | |||

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 39.5 (8.9, 78.7) | 0.019 | 0.038 | 0.126 | 0.551 | 0.638 | 0.925 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | −22.3 (−36.6, −4.9) | 0.027 | <0.001 | 0.881 | 0.295 | 0.285 | 0.723 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | −34.6 (−47.8, −18.1) | 0.002 | 0.090 | 0.911 | 0.196 | 0.954 | 0.730 |

| Progesterone (ng/dL) | −49.2 (−68.3, −18.5) | 0.014 | 0.046 | 0.821 | 0.315 | 0.750 | 0.343 |

| PFAS Exposure Index * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premenopause (N = 337) | Postmenopause (N = 275) | |||

| % Change per IQR (95% CI) | p Value | % Change per IQR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 54.7 (15.5, 107.2) | 0.010 | 3.5 (−11.6, 21.2) | 0.681 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | −30.7 (−43.4, −15.2) | 0.004 | 3.5 (−3.3, 10.7) | 0.397 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | −38.3 (−52.9, −19.1) | 0.002 | −10.8 (−27.2, 9.2) | 0.315 |

| Progesterone (ng/dL) | −62.7 (−79.2, −33.1) | 0.005 | −5.6 (−22.9, 15.6) | 0.606 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Y.-W.; Chen, C.-W.; Lin, H.-C.; Su, T.-C.; Wang, C.; Lin, C.-Y. Associations Between PFAS Exposure and HPG Axis Hormones in U.S. Women. Life 2025, 15, 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121923

Fang Y-W, Chen C-W, Lin H-C, Su T-C, Wang C, Lin C-Y. Associations Between PFAS Exposure and HPG Axis Hormones in U.S. Women. Life. 2025; 15(12):1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121923

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Yu-Wei, Ching-Way Chen, Hsuan-Cheng Lin, Ta-Chen Su, Chikang Wang, and Chien-Yu Lin. 2025. "Associations Between PFAS Exposure and HPG Axis Hormones in U.S. Women" Life 15, no. 12: 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121923

APA StyleFang, Y.-W., Chen, C.-W., Lin, H.-C., Su, T.-C., Wang, C., & Lin, C.-Y. (2025). Associations Between PFAS Exposure and HPG Axis Hormones in U.S. Women. Life, 15(12), 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121923