1. Introduction

Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC) is a rare malignant epithelial tumor of the kidney arising from intercalated cells of the distal nephron. Cancer development is driven by the interplay of genetic mutations and environmental exposures, which disrupt critical cellular processes including DNA repair, cell-cycle regulation, apoptosis, and tissue homeostasis, ultimately promoting uncontrolled proliferation and tumor formation [

1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies chRCC as a distinct entity within the category of “Oncocytic and Chromophobe Renal Tumors” [

2]. Although some studies have proposed the existence of chRCC subtypes, the WHO does not currently endorse any formal variants due to the absence of meaningful prognostic differences [

2]. Instead, the WHO recognizes two primary histologic patterns: “classic” and “eosinophilic” [

2].

In the United States, chRCC accounts for approximately 3250 new cases annually, representing roughly 5% of all renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) [

3]. Individuals with Birt Hogg Dube syndrome, family history of RCC, or a history of smoking or hypertension are at a higher predisposition to chRCC [

3,

4].

Clinically, chRCC is often asymptomatic at early stages, with patients manifesting symptoms such as flank pain or hematuria in later stages [

3,

5]. Patients with chRCC have a median survival of approximately 29 months, underscoring the unfavorable prognosis associated with advanced disease and the need for improved prognostic tools and therapeutic approaches [

6].

Systemic therapy options for chRCC remain limited. Although VEGF-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as sunitinib and cabozantinib, have demonstrated modest activity in non-clear cell RCC, their efficacy in chRCC is markedly lower compared to clear cell RCC [

5]. Similarly, immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown inconsistent response patterns in chRCC, reflecting the unique biology of this subtype [

5]. As a result, treatment strategies for advanced chRCC remain challenging, underscoring the need for improved molecular characterization to guide precision therapeutic development.

This study represents the largest multi-institutional real-world genomic characterization of chRCC to date and provides expanded mutation frequency estimates, exploratory demographic analyses, and pathway-level interpretation across heterogeneous platforms. By integrating molecular and demographic data, this investigation aims to identify potential therapeutic targets and molecular drivers for the development of more precise and effective treatments for chRCC patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This was deemed exempt from institutional review board (IRB) oversight by Creighton University (Phoenix, AZ, USA) as it exclusively utilized de-identified, publicly accessible data from the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE) database. Clinical and genomic data were accessed via the cBioPortal platform (v17.0-public) on 21 July 2025, encompassing cases archived from 2017 onward. The AACR GENIE repository compiles genomic sequencing data from 19 international cancer centers and reflects considerable heterogeneity in sequencing methodologies, including whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and targeted gene panels ranging from 50 to 555 genes. Because sequencing panels varied (50–555 genes) and varied across institutions, mutation absence may reflect non-coverage rather than true wild-type status. Rare germline variants may have also persisted as a result of the sequencing being tumor-only. Sequencing depth varied by platform: targeted panels achieved coverage exceeding 500×, WES had an average depth of ~150×, and WGS reached ~30× coverage. For chRCC, 99.4% of samples were sequenced using targeted gene panels, 0.6% with WES, and 0.0% with WGS. Regarding sample composition, approximately 70% of specimens in our chRCC cohort were derived from primary tumors and 99.5% of cases were tumor tissue samples, with a small proportion (0.5%) consisting of cfDNA. Matched tumor–normal information was not explicitly annotated, limiting the ability to exclude germline variants across the cohort.

Our study cohort consisted of patients with a confirmed pathological diagnosis of ChRCC, identified from a larger pool of renal cell carcinoma cases. Tumor samples were categorized as either primary (originating from the initial tumor site) or metastatic (from distant sites). Differences in gene-level mutation frequencies between primary and metastatic tumors were analyzed using a chi-squared test, comparing the proportion of mutated samples in each group. The dataset encompassed somatic mutation profiles, histological classifications, and clinical demographic information, including race, sex, and age. We also analyzed copy number alterations (CNAs), specifically targeting homozygous deletions and amplifications, and determined the frequency of recurrent events. Although panel designs varied by institution, most included core oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, PTEN, and KMT2C.

While each participating institution applied its own pipeline for somatic variant calling and annotation, all followed GENIE harmonization standards as defined by Genome NEXUS. Commonly used tools included GATK for variant detection and ANNOVAR for functional annotation, though specific software versions and parameter settings varied across sites. Despite these centralized harmonization efforts, some variability in bioinformatic processing likely persists both across and within contributing institutions. Clinical outcome and therapeutic response data are available for select cancer types within GENIE; however, treatment regimens were not recorded for chRCC.

All statistical computations were performed using R/RStudio (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Boston, MA, USA, version 4.5.1), with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Associations between categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test. For continuous variables, data distribution was assessed to determine normality. Student’s t-test was applied for normally distributed data, while the Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed variables. Multiple-testing correction was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate method for analyses involving simultaneous comparisons.

Mutation data were obtained from GENIE’s harmonized MAF (mutation annotation format) files, which provide standardized gene- and protein-level annotations across contributing institutions. Only nonsynonymous somatic mutations (missense, frameshift, nonsense, and splice-site) were retained, with inclusion criteria of variant allele frequency (VAF) ≥ 5% and sequencing coverage ≥ 100×. Nonsynonymous somatic variants were included regardless of predicted pathogenicity due to variability in annotation across GENIE institutions. As such, some reported alterations may represent passenger mutations rather than drivers. Synonymous mutations, variants of uncertain significance, and genes without established clinical relevance were excluded. Structural variants were not assessed, and any samples with missing data were also removed from analysis. Only one tumor sample per patient was included for calculation of mutation frequencies. All mutation frequency calculations were performed at the patient level.

3. Results

3.1. chRCC Patient Demographics

A total of 180 tumor samples representing 170 unique patients with chRCC were included in the analysis. Patient characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The cohort consisted of 90 males (52.9%) and 78 females (45.9%). Nearly all patients were adults (

n = 167), with only three pediatric cases identified. Ethnicity data showed that 120 patients (70.6%) were non-Hispanic/non-Spanish, 15 (8.8%) were Hispanic or Spanish, and 35 (20.6%) lacked recorded ethnicity. Regarding race, 115 patients (67.6%) were White, 8 (4.7%) were Asian, 6 (3.5%) were Black, 1 (0.6%) was Native American, 19 (11.2%) reported another racial background, and 21 (12.3%) had unreported racial information. Most tumors originated from primary sites (

n = 124; 68.9%), with 45 samples (25.0%) collected from metastatic lesions and 11 (6.1%) without site annotation.

Among the metastatic samples with available site annotation, the most common metastatic sites included lung, liver, bone, and lymph nodes. Although limited by incomplete reporting, these data provide insight into metastatic patterns in chRCC. Sequencing methodologies for the cohort consisted primarily of targeted gene panels (99.4%), with a minority of samples sequenced by whole-exome sequencing (0.6%). No samples underwent whole-genome sequencing.

3.2. Spectrum of Recurrent Mutations

The mutational landscape of chRCC is summarized in

Table 2.

p-values from comparisons with expected cell counts below 5 were excluded due to insufficient statistical reliability. Panel coverage varied significantly by institution; therefore, absence of a reported mutation does not confirm wild-type status. As summarized in

Table 2, alterations in

TP53 were most common (

n = 92; 51.1%), followed by

PTEN (

n = 29; 16.1%). Less frequent but recurrent mutations were observed in

TERT (

n = 12; 6.7%),

RB1 (

n = 10; 5.6%),

ATM (

n = 10; 5.6%), and

SETD2 (

n = 10; 5.6%). Additional recurrently mutated genes included

NOTCH1 (

n = 9; 5.0%),

KMT2D (

n = 8; 4.4%),

TET2 (

n = 7; 3.9%),

TSC2 (

n = 7; 3.9%),

ATRX (

n = 7; 3.9%),

FAT1 (

n = 6; 3.3%),

ZFHX3 (

n = 6; 3.3%),

APC (

n = 6; 3.3%), and

CHEK2 (

n = 5; 2.8%).

Functional Relevance of SETD2, PTEN, TP53, and TERT

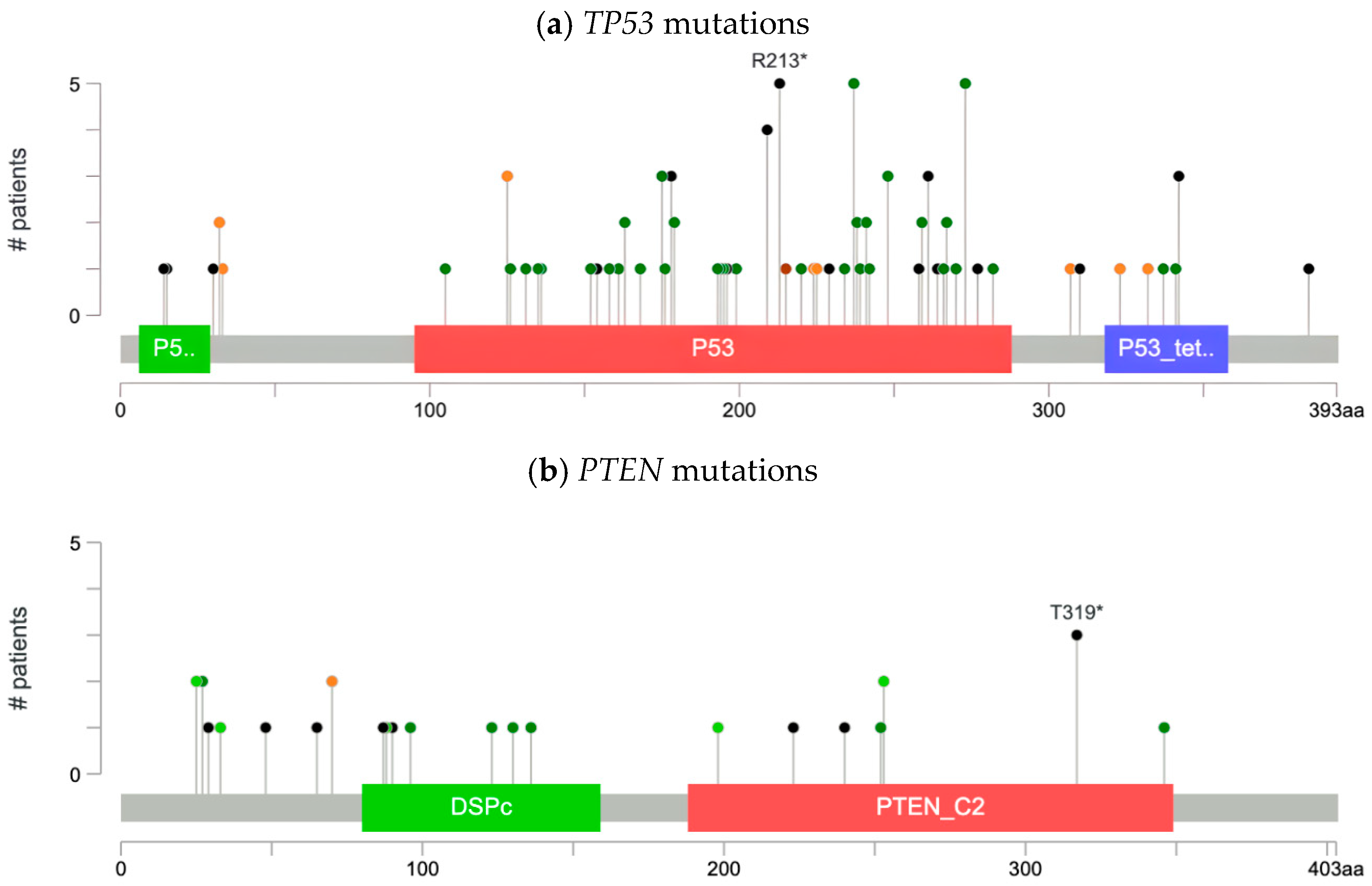

Our analysis characterized the types of mutations across frequently altered genes in our cohort:

SETD2,

PTEN,

TP53, and

TERT. As illustrated by the lollipop plot (

Figure 1a), we identified 53 missense, 29 truncation, 1 in-frame, 13 splice, and 1 fusion mutation in

TP53 (

n = 92), including recurrent hotspot alterations such as R213*, M237K, and R273H. R273H and M237K variants, which are both missense mutations, were found in the DNA-binding domain. R273H was found to increase cancer cell survival by erroneously activating the AKT signaling pathway. M237K, on the other hand, was identified by in vitro studies to render TP53 nonfunctional. R213*, a truncating mutation, was found to increase cancer cell proliferation and promote metastasis by aberrant localization to mitochondria. As a result, R213* is associated with poor prognosis in patients.

In

PTEN (

n = 29), we identified 9 missense mutations, 12 truncating mutations, 9 in-frame mutations, and 2 splice-site mutations, as illustrated in the lollipop plots (

Figure 1b).

SETD2 (

n = 10) and

TERT (

n = 12) mutations were dispersed throughout the gene, as illustrated by the lollipop plots (

Figure 1c,d). For

SETD2, we identified two splice mutations (

Figure 1c). While for

TERT, we identified 11 mutations of other types.

In addition to somatic mutations, we identified CNAs in 157 samples. Amplifications were observed in TERT, YAP1, and BIRC3 (n = 3; 1.9% for all), while homozygous deletions were detected in ERBB4 and RB1 (n = 3; 1.9% for all).

3.3. Sex- and Race-Associated Variants

Sex-stratified analysis identified isolated single-patient mutations in several genes, including

MCM4,

NUP214,

SSX2, and

TAF15 (

Table 3). Because each of these variants occurred in only one individual, they are considered exploratory observations without interpretable biological significance.

When stratified by race, isolated single-patient mutations were also observed (

Table 4). Examples include

PIK3C2B,

STAT3,

ERRFI1,

TSC1,

NCOR1,

PPM1D, and

ASXL2 in Black patients, and

FANCE,

SLFN11,

MLH3,

CCN6,

ALK, and

CDKN1B in Asian patients.

CHEK2 variants appeared in both Asian and White individuals. Because each event occurred in a single patient within very small racial subgroups (Black

n = 6; Asian

n = 8), these observations cannot be interpreted as recurring patterns or population-level associations.

Because all of these findings represent single mutation events within extremely small demographic subgroups, they should not be interpreted as biological enrichment or clinically meaningful differences. Instead, they serve as preliminary, hypothesis-generating signals that require validation in larger, more diverse datasets and cannot be generalized to broader populations.

3.4. Patterns of Co-Mutation and Exclusivity

Co-occurrence analysis demonstrated multiple significant gene–gene associations (

Table 5). The most frequent involved

TP53 with

PTEN (

n = 19; 31.1%;

p < 0.001).

TP53 also co-occurred with

RB1 (

n = 8; 13.6%;

p = 0.005) and

NOTCH1 (

n = 6; 10.2%;

p = 0.042). Additional co-mutation pairs included

PTEN with

KMT2D (

n = 3; 13.6%;

p = 0.004),

TSC2 with

FAT1 (

n = 2; 40.0%;

p = 0.001),

NOTCH1 with

KMT2D (

n = 2; 25.0%;

p = 0.007),

SETD2 with

TSC2 (

n = 2; 25.0%;

p = 0.009),

NOTCH1 with

TSC2 (

n = 2; 22.2%;

p = 0.013),

TERT with

RB1 (

n = 3; 20.0%;

p = 0.015),

RB1 with

TSC2 (

n = 2; 18.2%;

p = 0.022),

NOTCH1 with

ZFHX3 (

n = 1; 33.3%;

p = 0.030),

TSC2 with

ZFHX3 (

n = 1; 33.3%;

p = 0.030),

SETD2 with

NOTCH1 (

n = 2; 18.2%;

p = 0.031), and

PTEN with

RB1 (

n = 4; 14.8%;

p = 0.037). Gene–gene associations were evaluated using log odds ratios. Due to low event counts, only

TP53 and

PTEN demonstrated interpretable co-occurrence. Other associations lacked adequate support and are reported descriptively only.

Co-occurrence percentages were calculated by dividing the number of patients harboring both mutations by the number of patients with a mutation in either gene, defined as the sum of those with mutations in A only, B only, or both. Cases lacking alterations in both genes were excluded from the denominator.

4. Discussion

4.1. Subgroups and Mutational Landscape (Race, Gender, Age)

The aim of this investigation was to characterize the somatic mutational landscape of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC) using the AACR Project GENIE repository. Our cohort consisted primarily of adults (

n = 167, 98.2%), with only three pediatric patients. The scarcity of pediatric cases has hindered large-scale research in this population, leaving evidence-based treatment strategies poorly defined. The majority of patients in our cohort were White (67.6%), followed by Asian (4.7%) and Black (3.5%) patients. Sex stratification revealed a male-to-female distribution of 52.9% and 45.9%, respectively, with 1.2% unspecified. This pattern mirrors prior studies reporting balanced sex representation in chRCC [

7]. Due to sample limitations, subgroup observations that could not undergo statistical correction should be considered preliminary and exploratory only.

Sex- and race-stratified analyses in this cohort identified several genes with isolated single-patient mutations. In the sex-based analysis, variants in MCM4, NUP214, SSX2, and TAF15 were each detected in one female patient, with no corresponding cases in males. Similarly, the race-based analysis revealed single occurrences of mutations in genes such as PIK3C2B, STAT3, ERRFI1, TSC1, NCOR1, PPM1D, and ASXL2 among Black patients, and FANCE, SLFN11, MLH3, CCN6, ALK, and CDKN1B among Asian patients, with CHEK2 observed in individual Asian and White patients. However, because each of these findings reflects a single event within very small demographic subgroups (Black n = 6; Asian n = 8), they do not represent reproducible differences or reliable subgroup-specific patterns.

Given the extremely limited number of events and the absence of recurrent signals within these populations, these demographic observations should be interpreted solely as descriptive and exploratory. They do not support conclusions about biological, mechanistic, or prognostic differences based on sex or race. Instead, these isolated findings highlight areas that may warrant evaluation in larger, more diverse genomic datasets capable of supporting statistically meaningful subgroup analysis.

4.2. Commonly Mutated Genes and Altered Pathways

Genetic analysis of our cohort revealed substantial heterogeneity across multiple signaling pathways, including Hippo, NOTCH, chromosome stability, epigenetic regulation, and, most prominently, the p53 and PI3K/mTOR pathways. The most frequently altered genes were the tumor suppressors TP53 (n = 92, 51.1%) and PTEN (n = 29, 16.1%), implicating the p53 and mTOR pathways in tumorigenesis. Compared with TCGA findings, which reported TP53 mutation rates of ~32% and PTEN mutations of ~9%, our cohort demonstrated higher frequencies (51.1% and 16.1%, respectively). The higher mutation frequencies may also have been a result of differences in panel design, patient selection, or inclusion of variants of uncertain significance. Mutations in genes without known relevance to renal tumorigenesis (e.g., SSX2, CCN6, ASXL2) are likely incidental findings related to broad panel coverage rather than biologically meaningful drivers. In addition, single-occurrence mutations such as SLFN11 or ALK may reflect artifacts of panel coverage or low VAF and should be interpreted with caution. Additional alterations included missense and splicing mutations in TSC2 (n = 7, 3.9%), a negative regulator of the mTOR pathway, and missense variants in CHEK2 and ATM, both critical regulators of the p53 pathway.

Deep deletions were identified in genes involved in cell differentiation (ZFHX3, n = 6, 3.3%; NOTCH1, n = 9, 5.0%) and cell cycle regulation (RB1, n = 10, 5.6%). Mutations affecting chromosomal stability were also prevalent, particularly within telomerase-maintenance alleles (TERT, n = 12, 6.7%; ATRX, n = 7, 3.9%), DNA damage response and repair genes (ATM, n = 10, 5.6%; SETD2, n = 10, 5.6%; CHEK2, n = 5, 2.8%), and epigenetic modulators (KMT2D, n = 8, 4.4%; TET2, n = 7, 3.9%). SETD2 (n = 10, 5.6%) and TERT (n = 12, 6.7%) truncations also affected chromatin remodeling machinery. SETD2 alterations consisted primarily of truncating variants consistent with loss of histone methyltransferase activity, while TERT promoter mutations reflect activation through upstream regulatory disruption. Mutations involving the Hippo pathway were identified in FAT1 (n = 6, 3.3%) and APC (n = 6, 3.3%).

4.2.1. TP53/ATM/CHEK2 p53 Pathway

Alterations in the p53 tumor suppressor pathway have been extensively documented in RCC, functioning both as early drivers of tumorigenesis and as contributors to tumor progression [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Within our cohort, we observed frequent mutations in

TP53 (

n = 92, 51.1%),

ATM (

n = 10, 5.6%), and

CHEK2 (

n = 5, 2.8%), suggesting that most alterations within the p53 pathway occur through disruption of its DNA damage response mechanism.

ATM and

CHEK2 are upstream activators of the p53 protein, encoded by

TP53. In response to DNA damage,

ATM activates

CHEK2, which subsequently stabilizes p53 by preventing degradation through the MDM2–MDM4 protein complex [

12,

13]. Activated p53 then induces cell cycle arrest to facilitate DNA repair or triggers apoptosis when damage is irreparable [

12].

These findings suggest that pharmacologic activation of the p53 pathway may represent a promising therapeutic strategy to restore DNA damage response signaling in chRCC. MDM2 inhibitors, such as APG-115, Nutlin-3a, and low dosage of actinomycin D, enhance p53 activity by preventing formation of the MDM2–MDM4 complex [

14,

15]. Additionally, multi-targeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib, which are both approved for clear cell RCC, have also been reported to increase p53 expression. Notably, prior research has shown that Nutlin-3a enhances the efficacy of sorafenib by further upregulating p53 [

16]. Moreover, APR-246 (PRIMA-1MET), currently in phase III clinical trials, has demonstrated the ability to restore mutant p53 function while simultaneously upregulating p53 DNA damage response signaling [

17].

4.2.2. mTOR Pathway

Alterations in the mTOR pathway have been well documented in RCC and are implicated in tumor progression and metastasis [

9,

18,

19]. The mTOR pathway serves as a central regulator of cell growth, proliferation, and survival [

19]. In our cohort, approximately 20% of mutations are regulators of this pathway. Although mutations in

MTOR itself, previously reported in chRCC, were not detected, we observed frequent alterations in

PTEN (

n = 29, 16.1%) and

TSC2 (

n = 7, 3.9%) [

17,

20,

21].

PTEN and

TSC2 act as tumor suppressors by negatively regulating

AKT, a key activator of mTOR signaling [

22]. Under normal conditions,

PTEN dephosphorylates PIP3 to PIP2, thereby preventing AKT activation [

22]. PIP3 functions as a membrane docking site that enables AKT phosphorylation by PDK1 and mTORC2 [

22]. Loss of

PTEN disrupts this regulation, leading to constitutive AKT activation and persistent stimulation of the mTOR pathway [

22].

TSC1-TSC2 complex encodes a protein complex that represses mTOR [

22].

TSC2 encodes tuberin, a GTPase-activating protein that inhibits the small GTPase Rheb, one of the principal activators of mTOR [

22]. Mutations in

TSC2, or inhibition of

TSC2 function by excessive AKT activity, lead to persistent activation of the mTOR pathway [

22]. Mutations in

TSC1 or

TSC2 are also associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by benign tumors in the lungs, kidneys, or heart [

22,

23]. In TSC, hyperactivation of mTOR promotes degradation of insulin receptor substrates, reducing PI3K signaling, PIP3 formation, and AKT activation, thereby ultimately suppressing the mTOR pathway [

22].

Therapeutically, mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus and temsirolimus are commonly used in RCC to target mTORC1 [

24]. However, these agents may have limited efficacy in patients harboring concurrent

PTEN and

TSC2 mutations due to the feedback loop between AKT and mTORC1 [

25]. Inhibition of mTORC1 relieves suppression of AKT, resulting in increased AKT activity and continued upregulation of the mTOR pathway [

25]. Consequently, AKT inhibitors may represent a more promising therapeutic strategy for patients with

PTEN or

TSC2 mutations.

4.2.3. Hippo Pathway

Mutations in the

FAT1 gene (3.3%) have been implicated in RCC tumor progression through disruption of the Hippo signaling pathway, which controls tissue growth by regulating cell cycle pathways [

26]. In preclinical RCC models, the FAT1 protein functions as a tumor suppressor by acting as a cell-surface inhibitor of YAP1 [

27]. Loss-of-function mutations in

FAT1 result in constitutive YAP1 activation, which subsequently stimulates the ERK/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and RAS/RAF pathways, all of which play crucial roles in regulating cell differentiation [

27]. These findings suggest that YAP1 inhibitors may represent an effective treatment strategy for chRCC patients with

FAT1 mutations.

4.2.4. NOTCH Pathway

In RCC, dysregulation of the

NOTCH signaling pathway contributes to tumorigenesis by promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting cell differentiation [

28]. In our cohort, we identified alterations in

NOTCH1 (5%). Previous studies have reported mutations in other NOTCH receptors in chRCC; however,

NOTCH1 has been shown to exhibit particularly elevated expression in chRCC compared to other RCC subtypes [

28,

29,

30]. In a cohort of 52 clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients, knockdown of

NOTCH1 was shown to induce apoptosis, suggesting that targeted inhibition of

NOTCH1 may represent a promising therapeutic approach for eliminating malignant cells [

31].

4.3. Co-Occurrence Patterns and Functional Implications

In our chRCC cohort, we observed a high frequency of co-occurring mutations in

TP53 and

PTEN (

n = 19, 31.1%,

p < 0.001),

TSC2 and

FAT1 (

n = 2, 40.0%,

p = 0.001), and

PTEN and

KMT2D (

n = 3, 13.6%,

p = 0.004). Although no mutually exclusive mutation pairs were identified, prior studies in RCC have reported recurrent alterations in

TP53 and

PTEN, with chRCC exhibiting particularly high mutation rates in both genes [

5,

19,

20,

31]. Furthermore,

TP53 and

PTEN mutations have been shown to accumulate during metastatic progression in chRCC, suggesting that their co-occurrence may serve as a potential biomarker of metastatic disease [

9].

4.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations inherent to the AACR Project GENIE repository. First, demographic analyses are limited by extremely small subgroup sizes and should be interpreted with caution. Although one sample per patient was used for frequency calculations, potential institutional clustering effects may influence observed patterns. Second, the absence of treatment response or survival data precluded analysis of the association between therapy response and mutational profiles, as well as evaluation of treatment-induced genomic alterations driving tumor progression. Third, the repository’s sequencing data were aggregated from multiple institutional centers, which may introduce heterogeneity in the sequencing platforms used in the dataset. Fourth, the lack of longitudinal samples from individual patients restricted our ability to assess temporal dynamics of mutational patterns and their role in metastatic progression. This limitation was compounded by the integration of both primary and metastatic samples, regardless of chRCC subtype identity, into a single dataset. Fifth, because sequencing panels varied (50–555 genes) and varied across institutions, mutation absence may reflect non-coverage rather than true wild-type status. Rare germline variants may have also persisted as a result of the sequencing being tumor-only. Sixth, the absence of transcriptomic data prevented evaluation of how mutations influence gene expression or downstream pathway activity. This gap was particularly limiting for genes involved in epigenetic regulation, such as ATRX and TET2, and for exploring the contribution of miRNA to chRCC pathogenesis. Seventh, the lack of methylation data obstructed analysis of DNA methylation patterns and their role in tumor progression. Eighth, inclusion of multiple tumor samples from the same patient may have introduced bias; however, prior reports suggest that this does not significantly impact overall findings. Finally, the absence of immunohistochemistry data limited our ability to correlate mutation patterns with protein expression or assess immune-related biomarkers.

5. Conclusions

By leveraging a large, multi-institutional genomic dataset, this study provides a comprehensive characterization of the somatic mutational landscape of chRCC. These findings provide preliminary molecular insights that may be hypothesis-generating for future precision oncology studies, though they cannot inform clinical practice without functional or outcome validation. Moving forward, incorporation of multi-omics data, longitudinal sampling, and treatment information will be essential to contextualize mutation patterns, clarify their functional significance, and translate genomic discoveries into clinically actionable insights. Together, these efforts highlight the promise of developing personalized treatments tailored to chRCC to improve outcomes for patients with this rare and understudied subtype of RCC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., B.H., P.T.S., K.B., and A.T.; methodology, A.S. and B.H.; validation, G.S.S., T.J.M., A.S., and B.H.; formal analysis, G.S.S., T.J.M., A.S., and B.H.; data curation, A.G., G.S.S., and N.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., G.S.S., E.M., and N.T.; writing—review and editing, A.G., G.S.S., E.M., N.T., T.J.M., A.S., B.H., P.T.S., K.B., and A.T.; visualization, G.S.S., T.J.M., A.S., and B.H.; supervision, P.T.S., K.B., and A.T.; project administration, P.T.S., K.B., and A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the AACR Project GENIE is an open-access cancer genomics resource that includes de- identified patient information. This significantly reduces potential harm to individuals and removes the requirement for obtaining consent from each participant.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this study relied solely on de- identified data obtained from the publicly accessible AACR Project GENIE database, which does not require individual informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: AACR, American Association for Cancer Research; AKT, Protein Kinase B; ALK, Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase; ATM, Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated; ATR, Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-related; BRAF, v-Raf Murine Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog B; CDKN2A, Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A; chRCC, Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma; CNA, Copy Number Alteration; COSMIC, Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer; EGFR, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; ERBB2, Erb-B2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 2; FLCN, Folliculin; GENE, Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange; GENIE, Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange; indel, Insertion or Deletion; KEAP1, Kelch-like ECH-associated Protein 1; mTOR, Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin; ncRCC, Non–Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma; NGS, Next-Generation Sequencing; NRAS, Neuroblastoma RAS Viral Oncogene Homolog; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase; PTEN, Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog; RCC, Renal Cell Carcinoma; RHEB, Ras Homolog Enriched in Brain; ROS1, ROS Proto-Oncogene 1; RTK, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase; SDH, Succinate Dehydrogenase; SNV, Single Nucleotide Variant; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TSC1, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1; TSC2, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 2; VHL, Von Hippel–Lindau; VUS, Variants of Uncertain Significance.

References

- Bhat, A.S.; Ahmed, M.; Abbas, K.; Mustafa, M.; Alam, M.; Salem, M.A.S.; Islam, S.; Tantry, I.Q.; Singh, Y.; Fatima, M.; et al. Cancer Initiation and Progression: A Comprehensive Review of Carcinogenic Substances, Anti-Cancer Therapies, and Regulatory Frameworks. Asian J. Res. Biochem. 2024, 14, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghehbandan, R.; Siadat, F.; Trpkov, K. What’s new in the WHO 2022 classification of kidney tumours? Pathol.-J. Ital. Soc. Anat. Pathol. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2023, 115, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A.A.; Idowu, N.A.; Rasheed, M.W.; Aderibigbe, O.A.; Olatide, O.O. Chromophobe: Arare histological variant of renal cell carcinoma. Ibom Med. J. 2023, 16, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znaor, A.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Laversanne, M.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. International Variations and Trends in Renal Cell Carcinoma Incidence and Mortality. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garje, R.; Elhag, D.; Yasin, H.A.; Acharya, L.; Vaena, D.; Dahmoush, L. Comprehensive review of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol 2021, 160, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Conde, E.; Duran, I. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: A review of an uncommon entity. Int. J. Urol. 2012, 19, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casuscelli, J.; Becerra, M.F.; Seier, K.; Manley, B.J.; Benfante, N.; Redzematovic, A.; Stief, C.G.; Hsieh, J.J.; Tickoo, S.K.; Reuter, V.E.; et al. Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results From a Large Single-Institution Series. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019, 17, 373–379.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amendolare, A.; Marzano, F.; Petruzzella, V.; Vacca, R.A.; Guerrini, L.; Pesole, G.; Sbisà, E.; Tullo, A. The Underestimated Role of the p53 Pathway in Renal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casuscelli, J.; Weinhold, N.; Gundem, G.; Wang, L.; Zabor, E.C.; Drill, E.; Wang, P.I.; Nanjangud, G.J.; Redzematovic, A.; Nargund, A.M.; et al. Genomic landscape and evolution of metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e92688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shvarts, O.; Seligson, D.; Lam, J.; Shi, T.; Horvath, S.; Figlin, R.; Belldegrun, A.; Pantuck, A.J. p53 is an Independent Predictor of Tumor Recurrence and Progression After Nephrectomy in Patients with Localized Renal Cell Carcinoma. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigeuner, R.; Ratschek, M.; Rehak, P.; Schips, L.; Langner, C. Value of p53 as a prognostic marker in histologic subtypes of renal cell carcinoma: A systematic analysis of primary and metastatic tumor tissue. Urology 2004, 63, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Kim, S.; Xiao, C.; Wang, R.H.; Coumoul, X.; Wang, X.; Li, W.M.; Xu, X.L.; De Soto, J.A.; Takai, H.; et al. ATM–Chk2–p53 activation prevents tumorigenesis at an expense of organ homeostasis upon Brca1 deficiency. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszno, J.; Kołosza, Z. Checkpoint Kinase 2 (CHEK2) Mutation in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Single-Center Experience. J. Kidney Cancer VHL 2018, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Lain, S.; Verma, C.S.; Fersht, A.R.; Lane, D.P. Awakening guardian angels: Drugging the p53 pathway. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haronikova, L.; Bonczek, O.; Zatloukalova, P.; Kokas-Zavadil, F.; Kucerikova, M.; Coates, P.J.; Fahraeus, R.; Vojtesek, B. Resistance mechanisms to inhibitors of p53-MDM2 interactions in cancer therapy: Can we overcome them? Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2021, 26, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsyayan, R.; Singhal, J.; Nagaprashantha, L.D.; Awasthi, S.; Singhal, S.S. Nutlin-3 enhances sorafenib efficacy in renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 2013, 52, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirtharaj, F.; Venkatesh, G.; Wojtas, B.; Nawafleh, H.H.; Shah Mahmood, A.; Nizami, Z.N.; Khan, M.S.; Thiery, J.; Chouaib, S. p53 reactivating small molecule PRIMA-1MET /APR-246 regulates genomic instability in MDA-MB-231 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 47, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudes, G.R. Targeting mTOR in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2009, 115, 2313–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan-Romero, J.M.; Beuselinck, B.; Santos, M.; Rodriguez-Moreno, J.F.; Lanillos, J.; Calsina, B.; Gutierrez, A.; Tang, K.; Lainez, N.; Puente, J.; et al. PTEN expression and mutations in TSC1, TSC2 and MTOR are associated with response to rapalogs in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Intl J. Cancer 2020, 146, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.F.; Ricketts, C.J.; Wang, M.; Yang, L.; Cherniack, A.D.; Shen, H.; Buhay, C.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.C.; Fahey, C.C. The Somatic Genomic Landscape of Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan-Romero, J.M.; Santos, M.; Lanillos, J.; Caleiras, E.; Anguera, G.; Maroto, P.; García-Donas, J.; de Velasco, G.; Martinez-Montes, Á.M.; Calsina, B.; et al. Molecular characterization of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma reveals mTOR pathway alterations in patients with poor outcome. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 2580–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Dibble, C.C.; Matsuzaki, M.; Manning, B.D. The TSC1-TSC2 Complex Is Required for Proper Activation of mTOR Complex 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 4104–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henske, E.P.; Cornejo, K.M.; Wu, C.L. Renal Cell Carcinoma in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Genes 2021, 12, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avulova, S.; Cheville, J.C.; Lohse, C.M.; Gupta, S.; Potretzke, T.A.; Tsivian, M.; Thompson, R.H.; Boorjian, S.A.; Leibovich, B.C.; Potretzke, A.M. Grading Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma: Evidence for a Four-tiered Classification Incorporating Coagulative Tumor Necrosis. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Gan, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, B.; Huangfu, Z.; Shi, X.; Wang, L. Research progress of the Hippo signaling pathway in renal cell carcinoma. Asian J. Urol. 2024, 11, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.G.; Saba, N.F.; Teng, Y. The diverse functions of FAT1 in cancer progression: Good, bad, or ugly? J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Sun, S.; Du, R.; Gao, J.; Ning, X.; Xie, H.; Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Fan, D. Expression and clinical significance of Notch receptors in human renal cell carcinoma. Pathology 2009, 41, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, Y.; Susztak, K. Notch in the kidney: Development and disease. J. Pathol. 2012, 226, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, L.M.A.; Villaamil, V.M.; Gallego, G.A.; Caínzos, I.S.; Campelo, R.G.; Rubira, L.V.; Estévez, S.V.; Mateos, L.L.; Perez, J.F.; Vázquez, M.R.; et al. Expression of Notch1 to -4 and their Ligands in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Tissue Microarray Study. Cancer Genom. 2011, 8, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Z.; Lin, J.; Huang, Y.; Lin, T.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, X. Notch 1 is a valuable therapeutic target against cell survival and proliferation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 3437–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).