Molecular, Physiological, and Histopathological Insights into the Protective Role of Equisetum arvense and Olea europaea Extracts Against Metronidazole-Induced Pancreatic Toxicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

- Group I (Control group): received distilled water.

- Group II (Metronidazole): received MTZ (400 mg/kg) only.

- Group III (Equisetum arvense group): received E. arvense (100 mg/kg).

- Group IV (Olea europaea): received O. europaea (400 mg/kg)

- Group V (MTZ + Equisetum arvense group): received MTZ (400 mg/kg) plus E. arvense (100 mg/kg).

- Group VI (MTZ + Olea europaea): received MTZ (400 mg/kg) plus O. europaea (400 mg/kg).

2.2. Drug

2.3. Ethical Approval and ARRIVE Guidelines Compliance

2.4. Preparation of Plant Extract

2.5. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

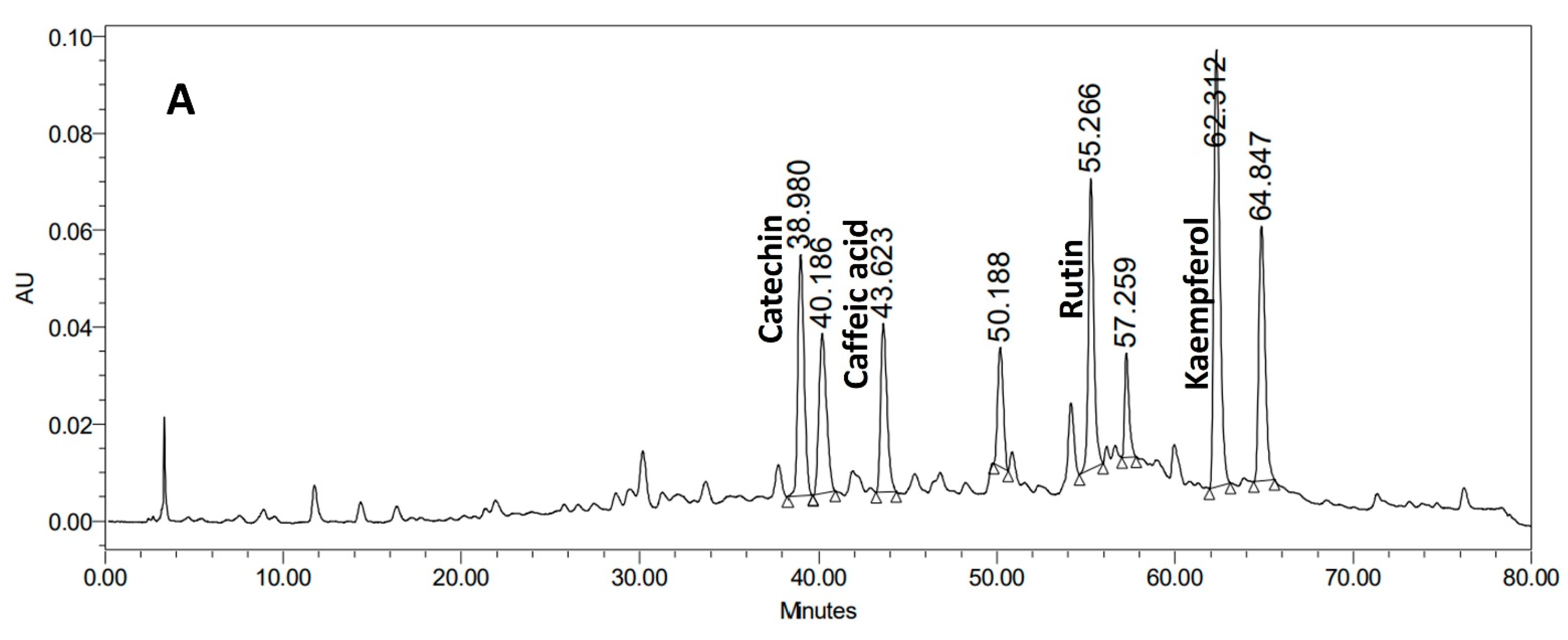

2.6. HPLC Characterization of Horsetail Ethanol Extract and Olive Leaves Aqueous Extract

2.7. Specimen and Tissue Preparation

2.8. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Parameters

2.9. qPCR Analysis of Pik3ca, AKT, Nrf-2, TNFα, and IL-1β Genes

2.10. Histopathological Examination

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. HPLC Characterization of Horsetail Ethanol Extract and Olive Leaves Aqueous Extract

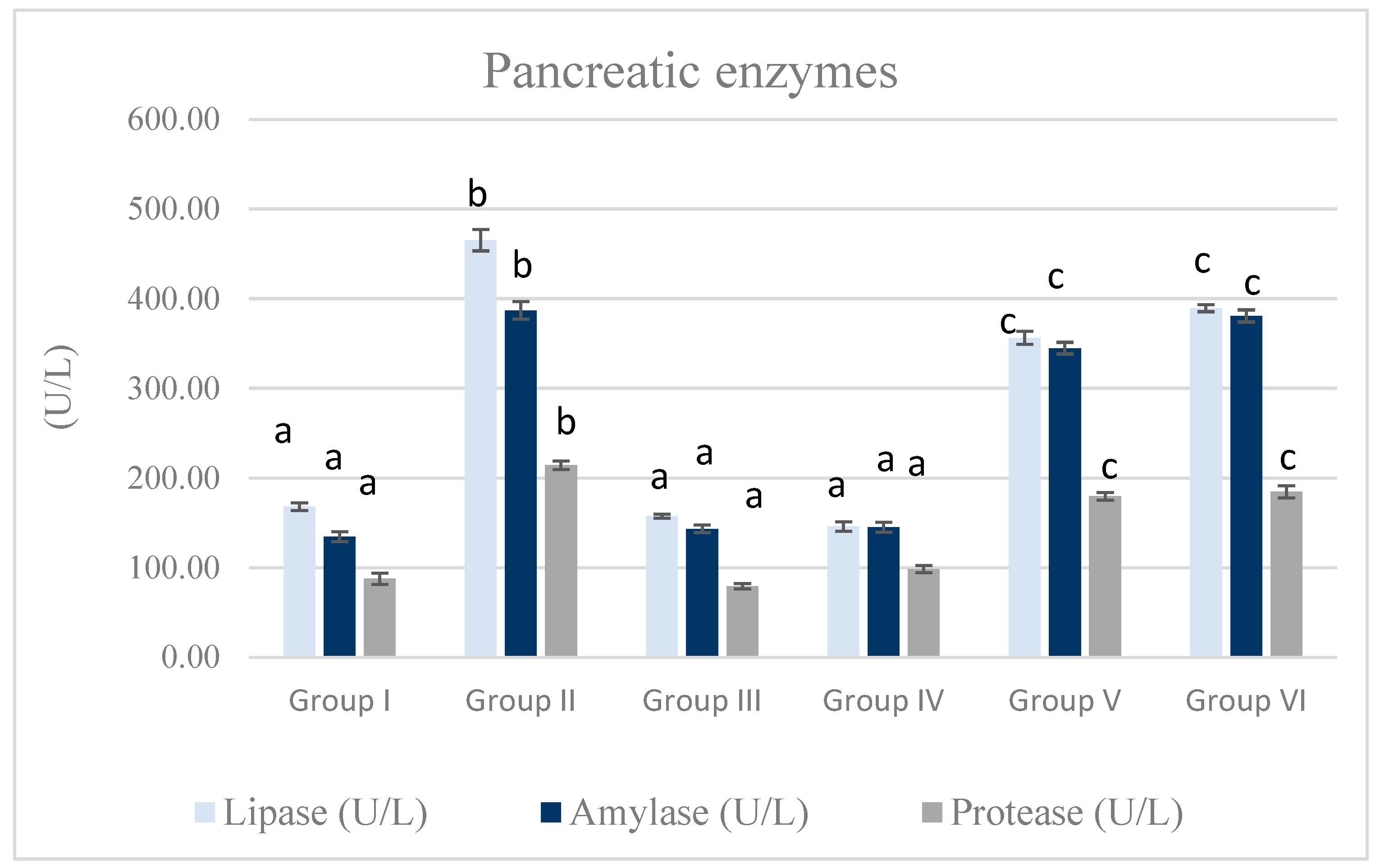

3.2. Serum Pancreatic Enzymes

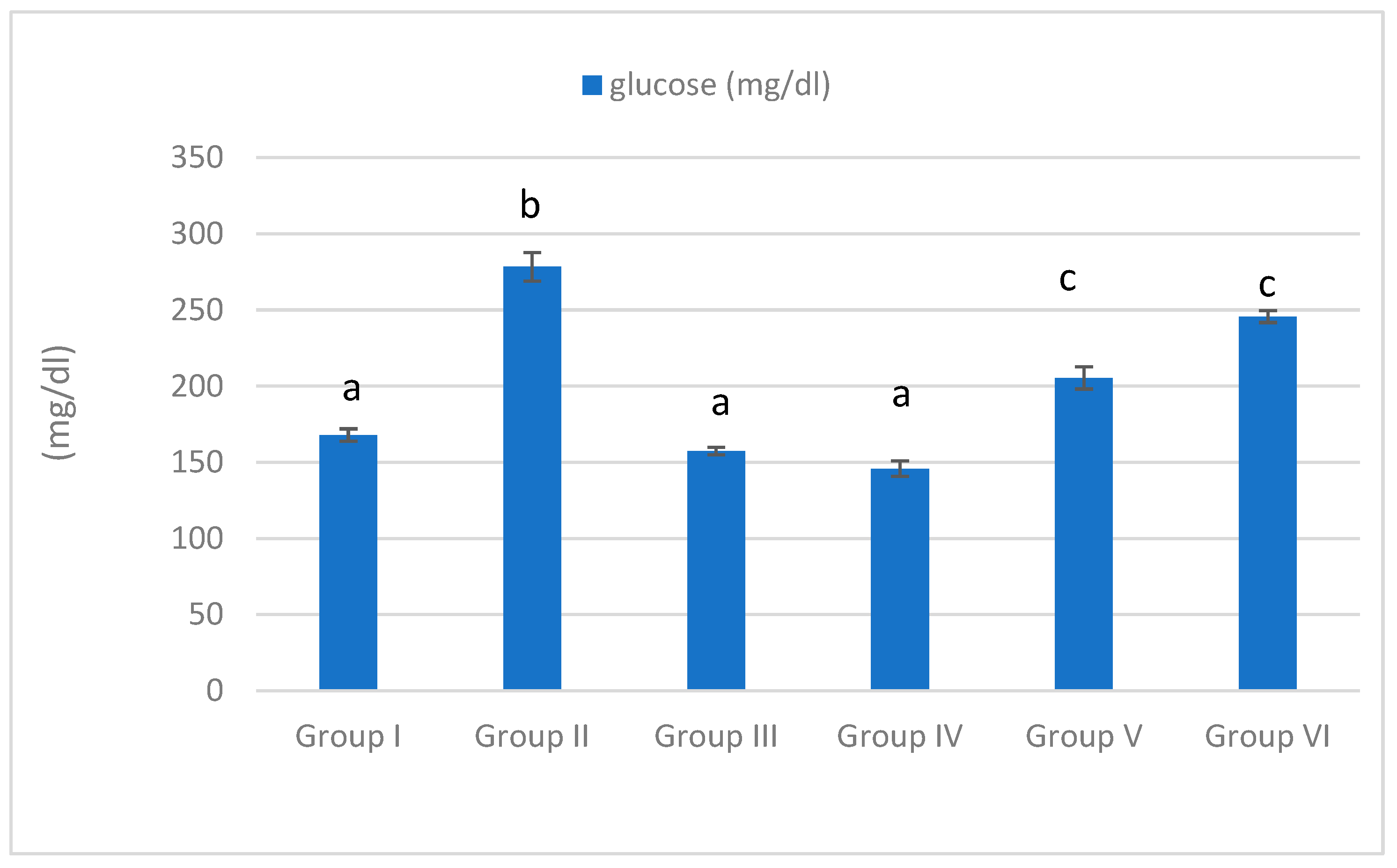

3.3. Serum Glucose Level

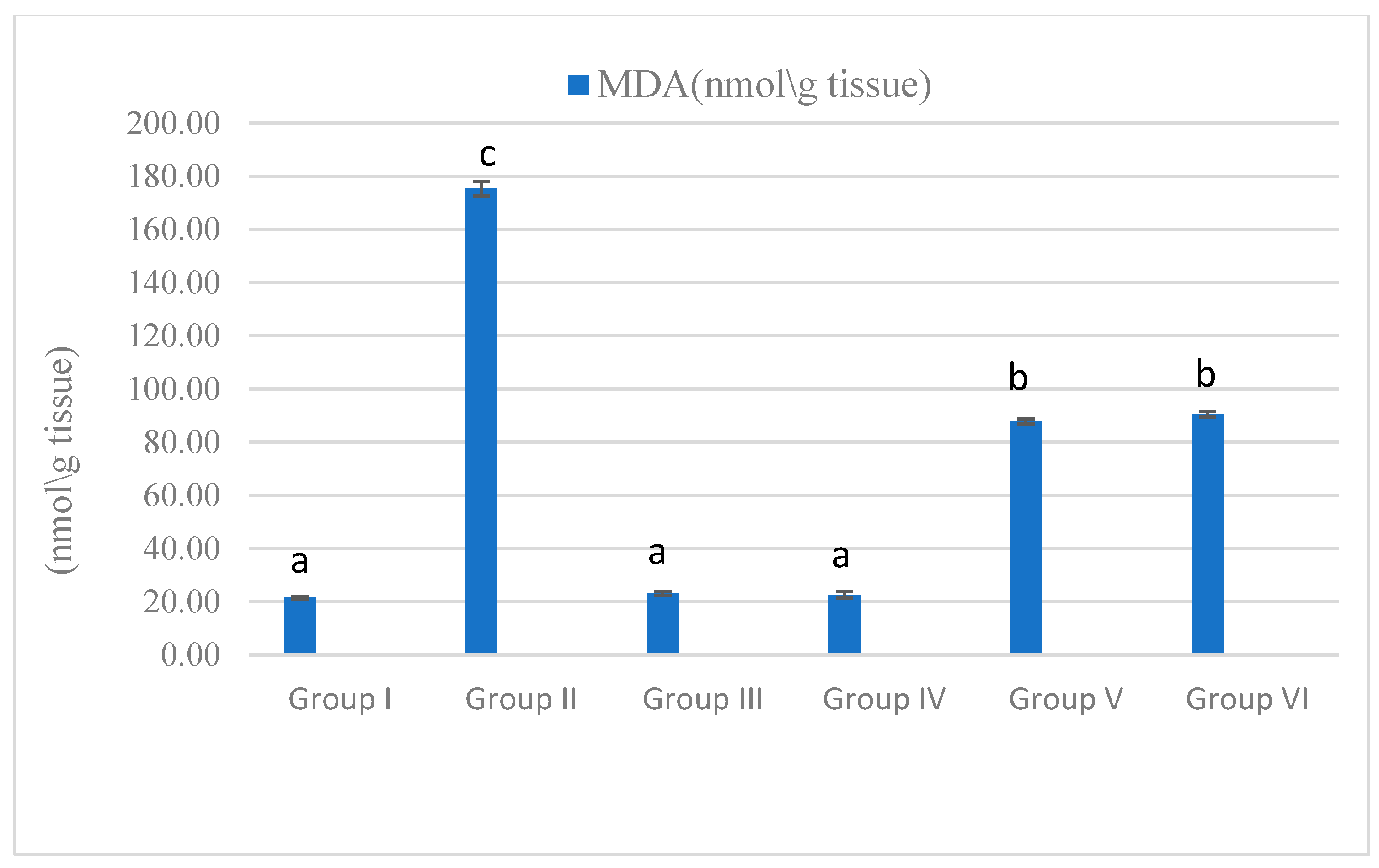

3.4. Antioxidant and Oxidative Stress

3.5. qPCR Analysis of Pik3ca, AKT, Nrf-2, TNFα, and IL-1β Genes

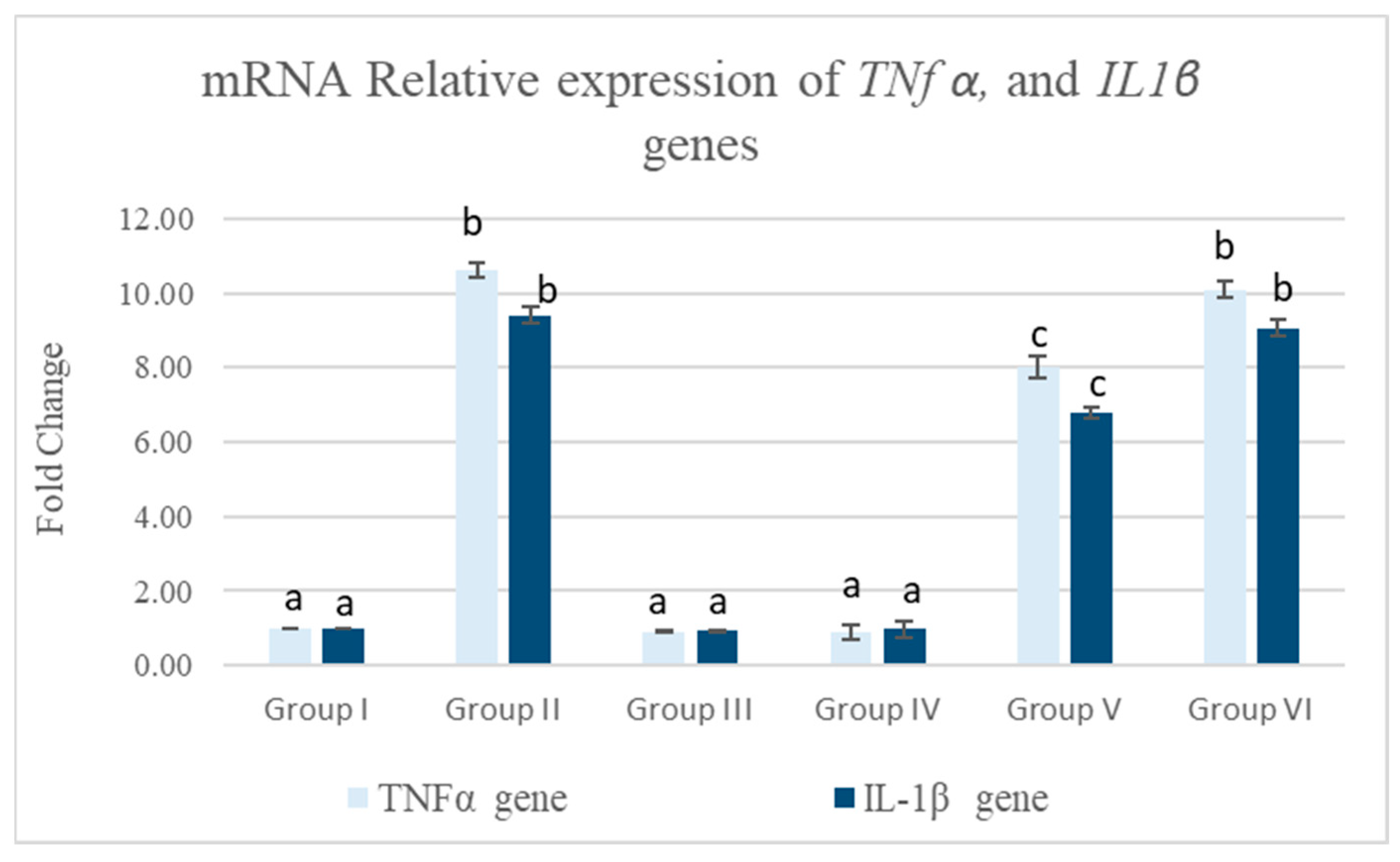

3.5.1. Pancreatic mRNA Relative Expression of TNFα and IL-1β Genes

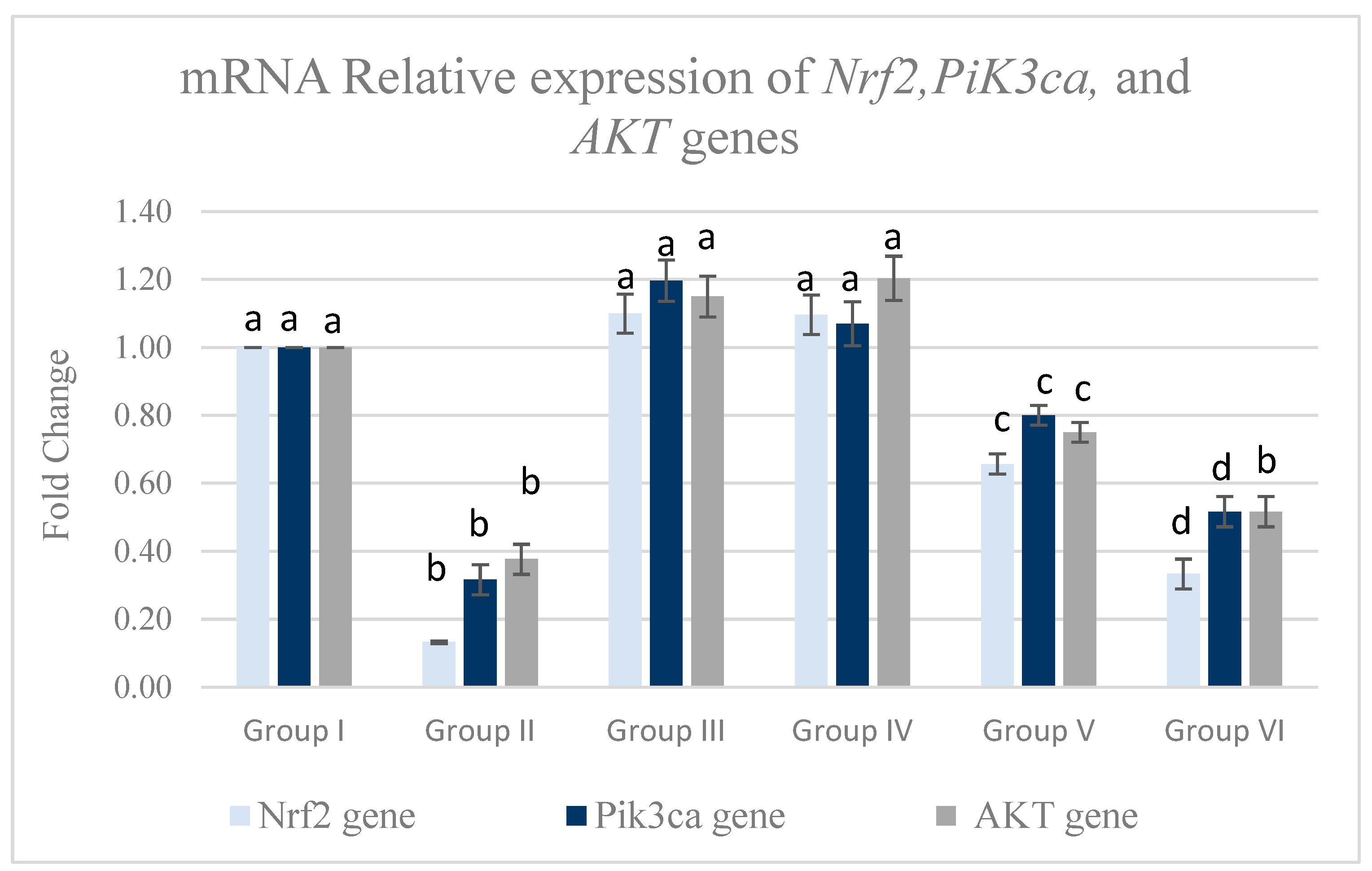

3.5.2. Pancreatic mRNA Relative Expression of Pik3ca, AKT, and Nrf-2 Genes

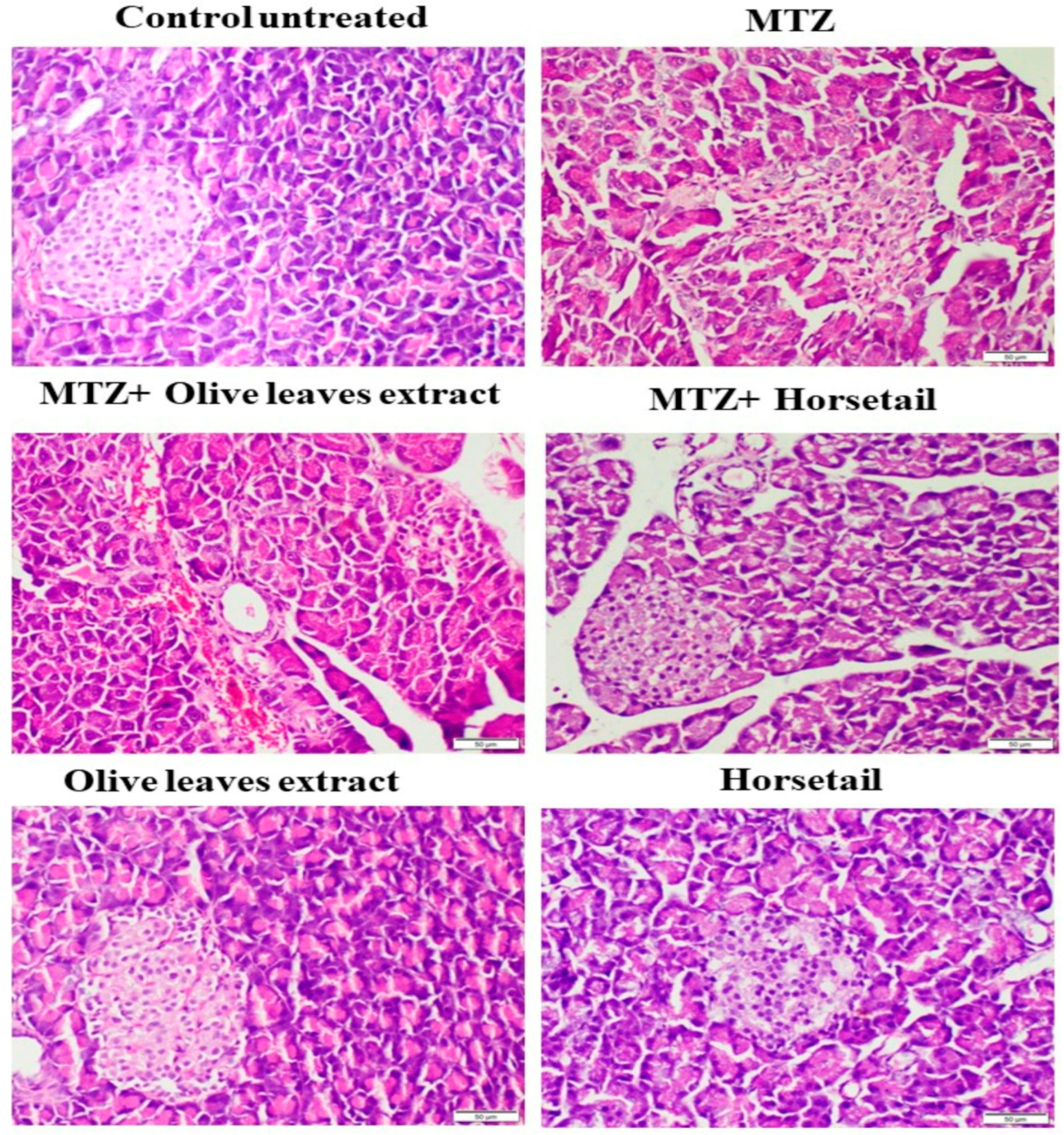

3.6. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Effects of Different Treatments on the Pancreatic Tissues

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Del Gaudio, A.; Covello, C.; Di Vincenzo, F.; De Lucia, S.S.; Mezza, T.; Nicoletti, A.; Siciliano, V.; Candelli, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Nista, E.C. Drug-Induced Acute Pancreatitis in Adults: Focus on Antimicrobial and Antiviral Drugs, a Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, I.; Naba, S.; Mohammad, E.; Kara, H.; Kais, Z. Metronidazole-Induced Pancreatitis: Is There Under-recognition? A Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Gastrointest. Med. 2019, 2019, 4840539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.; Marino, D.; Badalov, N.; Vugelman, M.; Tenner, S. Drug-Induced Acute Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Classification (Revised). Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekara, A.; Hamadouche, N.A.; Kahloula, K.; Harouat, S.; Tabbas, D.; Aoues, A. Effect of Pimpinella anisum L. (Aniseed) Aqueous Extract against Lead (Pb) Neurotoxicity: Neurobehavioral Study. Int. J. Neurosci. Behav. Sci. 2015, 3, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeer, M.; Abdelrahman, H.; Khalil, K. Effects of Pomegranate Peel and Olive Pomace Supplementation on Reproduction and Oxidative Status of Rabbit Doe. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 106, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, H.M.M.; Zeitoun, A.A.; Abd-Rabou, H.S.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Zeitoun, M.A.A.; El-Sohaimy, S.A. Antioxidant and Anti-Diabetic Properties of Olive (Olea europaea) Leaf Extracts: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallag, A.; Filip, G.A.; Olteanu, D.; Clichici, S.; Baldea, I.; Jurca, T.; Micle, O.; Vicaş, L.; Marian, E.; Soriţău, O.; et al. Equisetum arvense L. Extract Induces Antibacterial Activity and Modulates Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis in Endothelial Vascular Cells Exposed to Hyperosmotic Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3060525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukric, Z.; Topalić-Trivunović, L.; Pavičić, S.; Zabić, M.; Matos, S.; Davidović, A. Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Equisetum arvense L. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2013, 19, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedűs, C.; Muresan, M.; Badale, A.; Bombicz, M.; Varga, B.; Szilágyi, A.; Sinka, D.; Bácskay, I.; Popoviciu, M.; Magyar, I.; et al. SIRT1 Activation by Equisetum arvense L. (Horsetail) Modulates Insulin Sensitivity in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Molecules 2020, 25, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Attar, A.M.; Alsalmi, F.A. Effect of Olea europaea Leaves Extract on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in Male Albino Rats. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.H.; Awadalla, E.A.; Ali, R.A.; Fouad, S.S.; Abdel-Kahaar, E. Thiamine Deficiency and Oxidative Stress Induced by Prolonged Metronidazole Therapy Can Explain Its Side Effects of Neurotoxicity and Infertility in Experimental Animals: Effect of Grapefruit Co-Therapy. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of Total Phenolic Content and Other Oxidation Substrates in Plant Tissues Using Folin–Ciocalteu Reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, A.A.L.; Gomez, J.D.; Vattuone, M.A.; Isla, M.I. Antioxidant Activities of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz Extracts. Food Chem. 2006, 97, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emil, A.B.; Hassan, N.H.; Ibrahim, S.; Hassanen, E.I.; Eldin, Z.E.; Ali, S.E. Propolis Extract Nanoparticles Alleviate Diabetes-Induced Reproductive Dysfunction in Male Rats: Antidiabetic, Antioxidant, and Steroidogenesis Modulatory Role. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, P.; Prencipe, L.; Berti, G. Use of 3,5-Dichloro-2-Hydroxybenzenesulfonic Acid/4-Aminophenazone Chromogenic System in Direct Enzymic Assay of Uric Acid in Serum and Urine. Clin. Chem. 1980, 26, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghafar, N.S.; Hamed, R.I.; El-Saied, E.M.; Rashad, M.M.; Yasin, N.A.; Noshy, P.A. Protective effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles against liver and kidney toxicity induced by oxymetholone, a steroid doping agent: Modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and gene expression in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 505, 117574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; El-Maghraby, E.M.; Rashad, M.M.; Bashir, D.W. Iron overload induced submandibular glands toxicity in gamma irradiated rats with possible mitigation by hesperidin and rutin. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 25, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, N.A.; Bashir, D.W.; El-Leithy, E.M.; Tohamy, A.F.; Rashad, M.M.; Ali, G.E.; El-Saba, A.A.A. Polyethylene terephthalate nanoplastics-induced neurotoxicity in adult male Swiss albino mice with amelioration by betaine: A histopathological, neuro-chemical, and molecular investigation. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 9323–9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeer, M.R.; Rashad, M.M.; Youssef, F.S.; Ahmed, O.; Soliman, S.S.; Ali, G.E. Ameliorative effect of curcumin loaded nanoliposomes, a promising bioactive formulation, against the DBP-induced testicular damage. Reprod. Toxicol. 2025, 137, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuzaied, H.; Bashir, D.W.; Rashad, E.; Rashad, M.M.; Bawish, B.M.; El-Habback, H. Nature’s shield: Ginseng as a neuro-protective agent against titanium dioxide nanoparticle exposure. J. Mol. Histol. 2025, 56, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakeer, M.; Ahmed, O.; Sayed, F.; Ali, G.E.; Aljarba, N.; Zouganelis, G.; Rashad, M. Astragalus polysaccharides protect against di-n-butyl phthalate–induced testicular damage by modulating oxidative stress, apoptosis, and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in rats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1616186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesham, A.; Abass, M.; Abdou, H.; Fahmy, R.; Rashad, M.M.; Abdallah, A.A.; Mossallem, W.; Rehan, I.F.; Elnagar, A.; Zigo, F.; et al. Ozonated Saline Intradermal Injection: Promising Therapy for Accelerated Cutaneous Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1283679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashad, M.M.; Galal, M.K.; El-Behairy, , A.M.; Gouda, , E.M.; Moussa, , S.Z. Maternal exposure to di-n-butyl phthalate induces alterations of c-Myc gene, some apoptotic and growth related genes in pups’ testes. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2018, 34, 744–752. [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Gamble, M. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 6th ed.; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sura, M.E.; Heinrich, K.A.; Suseno, M. Metronidazole-Associated Pancreatitis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2000, 34, 1152–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligha, A.; Paul, C. Oxidative Effect of Metronidazole on the Testis of Wistar Rats. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.H.; Wang, G.Z.; Li, S.J. Antioxidation and ATPase Activity in the Gill of Mud Crab Scylla serrata under Cold Stress. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2007, 25, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.J.; Ahamed, M.; Kumar, S.; Siddiqui, H.; Patil, G.; Ashquin, M.; Ahmad, I. Nanotoxicity of Pure Silica Mediated through Oxidant Generation Rather Than Glutathione Depletion in Human Lung Epithelial Cells. Toxicology 2010, 276, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durairaj, A.; Vaiyapuri, T.S.; Kanti, M.U.; Malaya, G. Protective Activity and Antioxidant Potential of Lippia nodiflora Extract in Paracetamol-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Rats. Iran. J. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 7, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, M.; Singh, P. Tribulus terrestris Ameliorates Metronidazole-Induced Spermatogenic Inhibition and Testicular Oxidative Stress in the Laboratory Mouse. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2015, 47, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Hünerbein, A.; Getie, M.; Jäckel, A.; Neubert, R.H.H. Scavenging Properties of Metronidazole on Free-Oxygen Radicals in a Skin Lipid Model System. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moslemany, A.M.; Abd-Elfatah, M.H.; Tahoon, N.A.; Bahnasy, R.M.; Alotaibi, B.S.; Ghamry, H.I.; Shukry, M. Mechanistic Assessment of Anise Seeds and Clove Buds Against the Neurotoxicity Caused by Metronidazole in Rats: Possible Role of Antioxidants, Neurotransmitters, and Cytokines. Toxics 2023, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharati, A.; Moghbeli, M. PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway as a Critical Regulator of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Colorectal Tumor Cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Lin, W.N.; Cho, R.L.; Yang, C.C.; Yeh, Y.C.; Hsiao, L.D.; Yang, C.M. Induction of HO-1 by Mevastatin Mediated via a Nox/ROS-Dependent c-Src/PDGFRα/PI3K/Akt/Nrf2/ARE Cascade Suppresses TNF-α-Induced Lung Inflammation. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essafi, I.; Mechchate, H.; Amaghnouje, A.; Calarco, A.; Boukhira, S.; Noman, O.M.; Mothana, R.A.; Nasr, F.A.; Bekkari, H.; Bousta, D. Defatted Hydroethanolic Extract of Ammodaucus leucotrichus Cosson and Durieu Seeds: Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechchate, H.; Es-Safi, I.; Mohamed Al Kamaly, O.; Bousta, D. Insight into Gentisic Acid Antidiabetic Potential Using In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Molecules 2021, 26, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luanda, A.; Ripanda, A.; Makangara, J.J. Therapeutic Potential of Equisetum arvense L. for Management of Medical Conditions. Phytomedicine Plus 2023, 3, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründemann, C.; Lengen, K.; Sauer, B.; Garcia-Käufer, M.; Zehl, M.; Huber, R. Equisetum arvense (Common Horsetail) Modulates the Function of Inflammatory Immunocompetent Cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeer, M.R. Focus on the Effect of Dietary Pump kin (Cucurbita moschata) Seed Oil Supplementation on Productive Performance of Growing Rabbits. J. Appl. Vet. Sci. 2021, 6, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.; ElHawary, N.; Mohamed, S.; Hashim, N.; Saleh, S.; Bakeer, M.; Sawiress, F. Effect of Stem Cell Therapy on Gentamicin Induced Testicular Dysfunction in Rats. J. Health Med. Inform. 2017, 8, 1000263. [Google Scholar]

- Ragheb, E.M.; Alamri, Z. Efficacy of Equisetum arvense Extract Against Carbon Tetrachloride Induced Liver and Kidney Injury in Rats. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharmacol. Res. 2020, 10, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.I.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, R.A.; Ullah, A.; Rehman, S.; Ullah, B. Phytotoxic, Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity of Crude Methanolic Extract of Equisetum debile. Int. J. Biosci. 2013, 3, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, T.; Shad, M.A.; Nawaz, H.; Andaleeb, H.; Aslam, M. Biochemical, Phytochemical and Antioxidant Composition of Equisetum debile Roxb. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 7, 1000368. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Yu, H.-S.; Ra, M.-J.; Jung, S.-M.; Yu, J.-N.; Kim, J.-C.; Kim, K.H. Phytochemical Investigation of Equisetum arvense and Evaluation of Its Anti-Inflammatory Potential in TNFα/INFγ-Stimulated Keratinocytes. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahinler, S.Ş. Equisetum arvense L. In Novel Drug Targets with Traditional Herbal Medicines; Gürağaç Dereli, F.T., Ilhan, M., Belwal, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, F.; Miyauchi, M.; Chea, C.; Furusho, H.; Iwasaki, S.; Shimizu, R.; Ohta, K.; Nishihara, T.; Takata, T. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Glycyrrhizin with Equisetum arvense Extract. Odontology 2021, 109, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G.T.; de Oliveira, T.T.; Carneiro, M.A.A.; Cangussu, S.D.; Humberto, G.A.P.; Taylor, J.G.; Humberto, J.L. Antidiabetic Effect of Equisetum giganteum L. Extract on Alloxan-Diabetic Rabbit. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 112898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, S.; Azarbaizani, F.F.; Nejati, V. The Effect of Equisetum arvense L. (Equisetaceae) on Histological Changes of Pancreatic Beta-Cells in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 4236–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilian, M.; Heukamp, I.; Gregor, J.I.; Schimke, I.; Kristiansen, G.; Wenger, F.A. Fish Oil, but Not Soybean or Olive Oil-Enriched Infusion Decreases Histopathological Severity of Acute Pancreatitis in Rats Without Affecting Eicosanoid Synthesis. Inflammation 2011, 34, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Symbol | Gene Description | Accession Number | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pik3ca | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha | NM_133399.3 | F: 5′-TAGTGTCCGGGAAAATGGCT-3′ R: 5′-GGCATGCTCTTCGATCACAG-3′ |

| AKT | AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase 1 | NM_033230.3 | F: 5′-CTGCCCTTCTACAACCAGGA-3′ R: 5′-GTGCTGCATGATCTCCTTGG-3′ |

| Nrf 2 | Nuclear factor, erythroid 2-like 2 | NC_005102.4 | F: 5′-GGCCCTCAATAGTGCTCAG-3′ R: -5′-TAGGCACCTGTGGCAGATTC-3′ |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha | NM_012675.3 | F: 5′-ACACACGAGACGCTGAAGTA-3′ R: 5′-GGAACAGTCTGGGAAGCTCT-3′ |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta | NM_031512.2 | F: 5′- TTGAGTCTGCACAGTTCCCC -3′ R: 5′- GTCCTGGGGAAGGCATTAGG -3′ |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde3-phosphate dehydrogenase | NC_005103.4 | F: -5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ R: -5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakeer, M.R.; Rashad, M.M.; Azouz, A.A.; Azouz, R.A.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Kadasah, S.F.; Shaalan, M.; Ali, A.M.; Issa, M.Y.; El-Samanoudy, S.I. Molecular, Physiological, and Histopathological Insights into the Protective Role of Equisetum arvense and Olea europaea Extracts Against Metronidazole-Induced Pancreatic Toxicity. Life 2025, 15, 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121907

Bakeer MR, Rashad MM, Azouz AA, Azouz RA, Alrefaei AF, Kadasah SF, Shaalan M, Ali AM, Issa MY, El-Samanoudy SI. Molecular, Physiological, and Histopathological Insights into the Protective Role of Equisetum arvense and Olea europaea Extracts Against Metronidazole-Induced Pancreatic Toxicity. Life. 2025; 15(12):1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121907

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakeer, Manal R., Maha M. Rashad, Asmaa A. Azouz, Rehab A. Azouz, Abdulmajeed Fahad Alrefaei, Sultan F. Kadasah, Mohamed Shaalan, Alaa M. Ali, Marwa Y. Issa, and Salma I. El-Samanoudy. 2025. "Molecular, Physiological, and Histopathological Insights into the Protective Role of Equisetum arvense and Olea europaea Extracts Against Metronidazole-Induced Pancreatic Toxicity" Life 15, no. 12: 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121907

APA StyleBakeer, M. R., Rashad, M. M., Azouz, A. A., Azouz, R. A., Alrefaei, A. F., Kadasah, S. F., Shaalan, M., Ali, A. M., Issa, M. Y., & El-Samanoudy, S. I. (2025). Molecular, Physiological, and Histopathological Insights into the Protective Role of Equisetum arvense and Olea europaea Extracts Against Metronidazole-Induced Pancreatic Toxicity. Life, 15(12), 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121907