Association Between Serum Ionized Calcium Levels and Neurological Outcomes in Patients with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

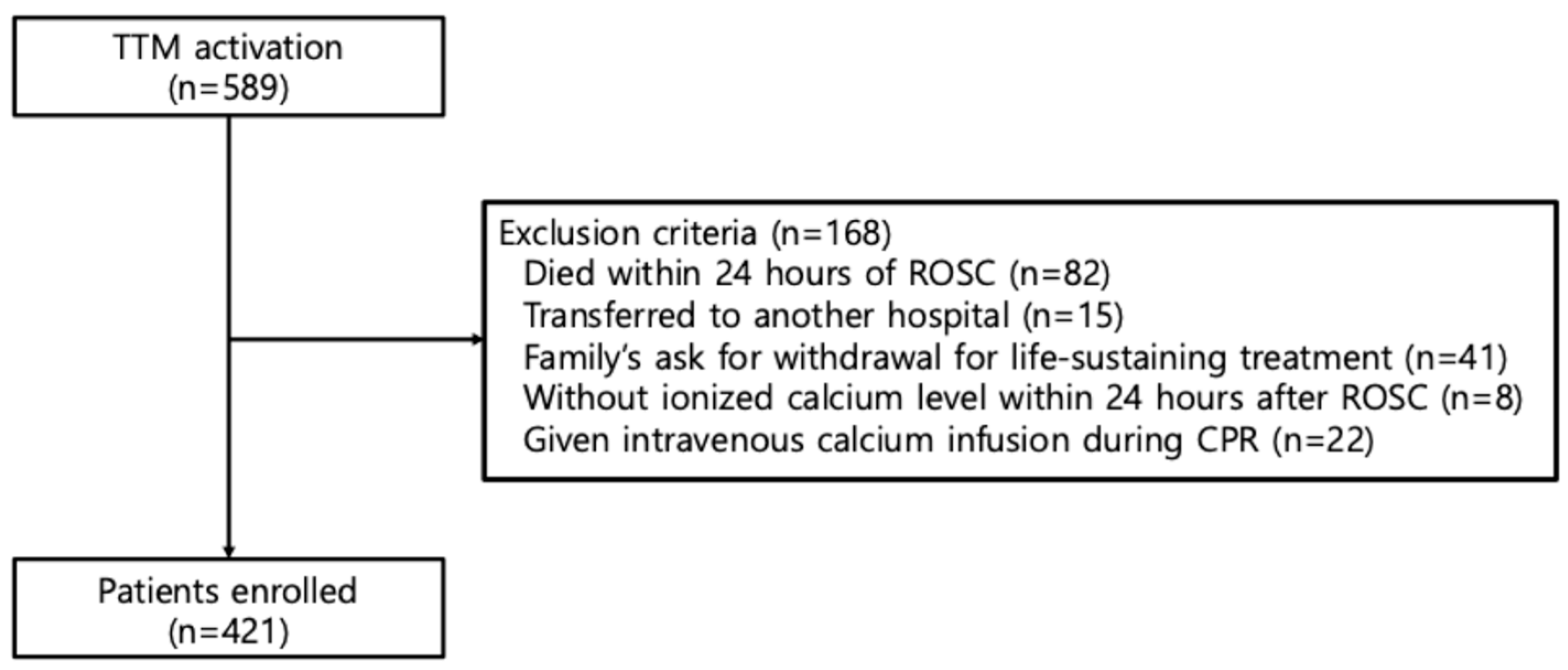

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Assessment of Serum Ionized Calcium

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Comparison of Model Performance (AIC and AUC) Among Models, Including Adjusted Ionized Calcium Measurements at Different Time Points (0, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h Post-ROSC), Controlling for the Corresponding Prior Time Period’s Calcium Infusion Dose

3.3. Final Multivariable Models Incorporating Longitudinal Adjusted Ionized Calcium Levels, While Controlling for Total Calcium Infusion Dose

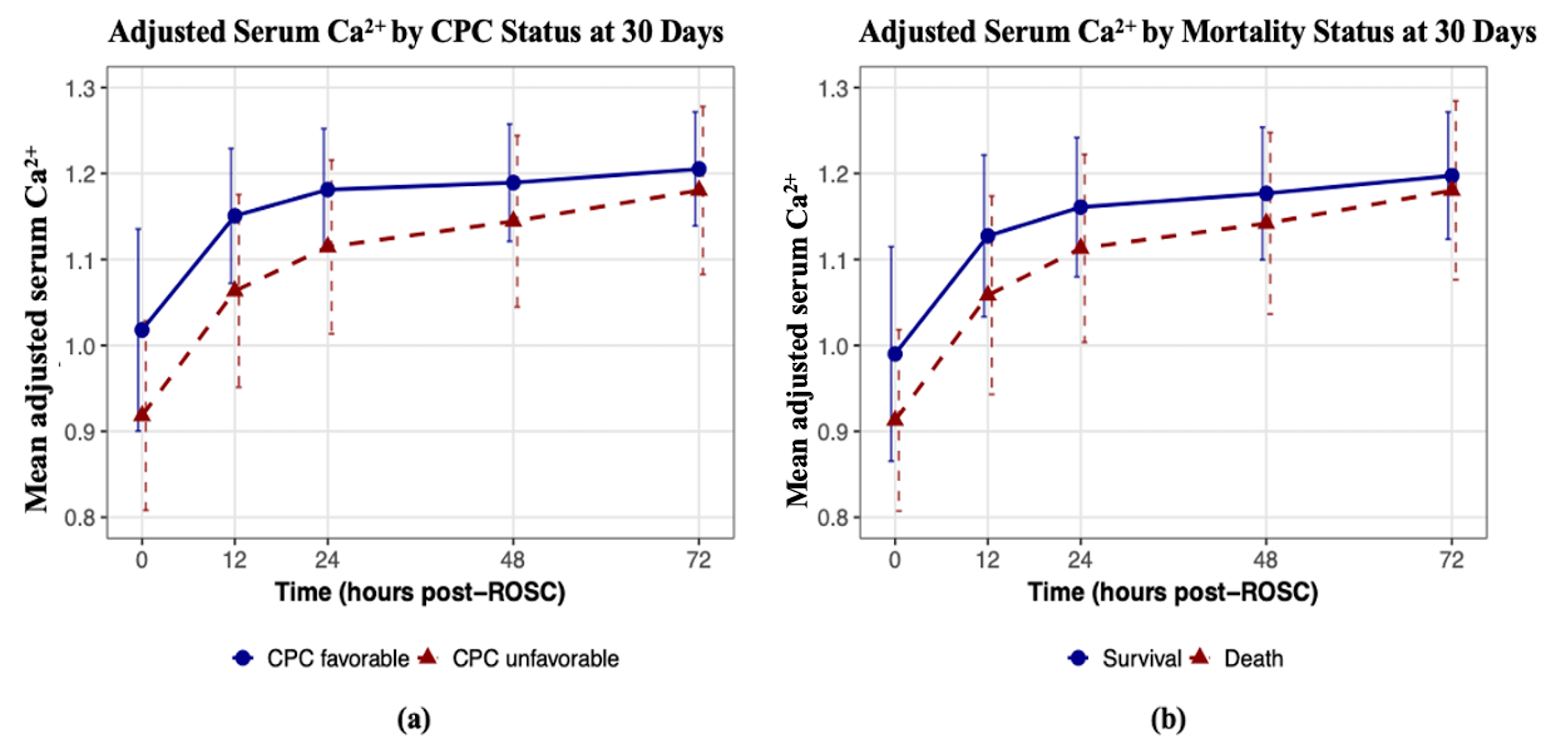

3.4. Trends of Mean Adjusted Ionized Calcium Levels over Time by Outcome Status

3.5. Comparison of AUC Among Multivariable Models with Different Levels of Information Regarding Longitudinal Adjusted Ionized Calcium Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OHCA | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest |

| TTM | Targeted temperature management |

| ROSC | Return of spontaneous circulation |

| CPC | Cerebral Performance Category |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| CP | Critical pathway |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

References

- Bougouin, W.; Lamhaut, L.; Marijon, E.; Jost, D.; Dumas, F.; Deye, N.; Beganton, F.; Empana, J.P.; Chazelle, E.; Cariou, A.; et al. Characteristics and prognosis of sudden cardiac death in Greater Paris: Population-based approach from the Paris Sudden Death Expertise Center (Paris-SDEC). Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemiale, V.; Dumas, F.; Mongardon, N.; Giovanetti, O.; Charpentier, J.; Chiche, J.D.; Carli, P.; Mira, J.P.; Nolan, J.; Cariou, A. Intensive care unit mortality after cardiac arrest: The relative contribution of shock and brain injury in a large cohort. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, F.; White, L.; Stubbs, B.A.; Cariou, A.; Rea, T.D. Long-term prognosis following resuscitation from out of hospital cardiac arrest: Role of percutaneous coronary intervention and therapeutic hypothermia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumar, R.W.; Nolan, J.P.; Adrie, C.; Aibiki, M.; Berg, R.A.; Böttiger, B.W.; Callaway, C.; Clark, R.S.; Geocadin, R.G.; Jauch, E.C.; et al. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation 2008, 118, 2452–2483. [Google Scholar]

- Adrie, C.; Adib-Conquy, M.; Laurent, I.; Monchi, M.; Vinsonneau, C.; Fitting, C.; Fraisse, F.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T.; Carli, P.; Spaulding, C.; et al. Successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation after cardiac arrest as a “sepsis-like” syndrome. Circulation 2002, 106, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeris, T.; Baines, C.P.; Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R.J. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 298, 229–317. [Google Scholar]

- Hossmann, K.A.; Sakaki, S.; Zimmerman, V. Cation activities in reversible ischemia of the cat brain. Stroke 1977, 8, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.B.; Sommers, H.M.; Kaltenbach, J.P.; West, J.J. Electrolyte Alterations in Acute Myocardial Ischemic Injury. Circ. Res. 1964, 14, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, T.; Chan, P.H. Reactive oxygen radicals and pathogenesis of neuronal death after cerebral ischemia. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2003, 5, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racay, P.; Tatarkova, Z.; Chomova, M.; Hatok, J.; Kaplan, P.; Dobrota, D. Mitochondrial calcium transport and mitochondrial dysfunction after global brain ischemia in rat hippocampus. Neurochem. Res. 2009, 34, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludhiadch, A.; Sharma, R.; Muriki, A.; Munshi, A. Role of Calcium Homeostasis in Ischemic Stroke: A Review. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2022, 21, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Mishra, V.N.; Chaurasia, R.N.; Joshi, D.; Pandey, V. Modes of Calcium Regulation in Ischemic Neuron. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2019, 34, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, B.; Ghildiyal, S.; Kharkwal, H. ML218 modulates calcium binding protein, oxidative stress, and inflammation during ischemia-reperfusion brain injury in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 982, 176919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Kastner, R.; Hossmann, K.A.; Grosse Ophoff, B. Relationship between metabolic recovery and the EEG prolonged ischemia of cat brain. Stroke 1986, 17, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L. Serum Calcium is Associated with Sudden Cardiac Arrest after Stroke: An Observational Multicenter Study of the eICU Database. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Huo, R.; Zhao, H.; Ying, Y. Association between serum calcium and prognosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke in ICU: Analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Hwang, S.O.; Jung, W.J.; Roh, Y.I.; Cha, K.C.; Shin, S.D.; Song, K.J.; Korean Cardiac Arrest Research Consortium (KoCARC) Investigators. Ionized calcium level at emergency department arrival is associated with return of spontaneous circulation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, T.; Watanabe, T.; Mukai-Yatagai, N.; Sasaki, N.; Furuse, Y.; Shirota, K.; Kato, M.; Yamamoto, K. Neurological Prognostic Value of Adjusted Ca(2+) Concentration in Adult Patients with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Int. Heart J. 2020, 61, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; You, J.S.; Lee, H.S.; Park, Y.S.; Park, I.; Chung, S.P. Multimodal approach for neurologic prognostication of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients undergoing targeted temperature management. Resuscitation 2019, 134, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, I.; Nadkarni, V.; Bahr, J.; Berg, R.A.; Billi, J.E.; Bossaert, L.; Cassan, P.; Coovadia, A.; D’Este, K.; Finn, J.L.; et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: Update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries: A statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the international liaison committee on resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa). Resuscitation 2004, 63, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Perman, S.M.; Elmer, J.; Maciel, C.B.; Uzendu, A.; May, T.; Mumma, B.E.; Bartos, J.A.; Rodriguez, A.J.; Kurz, M.C.; Panchal, A.R.; et al. 2023 American Heart Association Focused Update on Adult Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support: An Update to the American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2024, 149, e254–e273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.P.; Sandroni, C.; Cariou, A.; Cronberg, T.; D’Arrigo, S.; Haywood, K.; Hoedemaekers, A.; Lilja, G.; Nikolaou, N.; Olasveengen, T.M.; et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines 2025: Post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 2213–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittenberger, J.C.; Raina, K.; Holm, M.B.; Kim, Y.J.; Callaway, C.W. Association between Cerebral Performance Category, Modified Rankin Scale, and discharge disposition after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2011, 82, 1036–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, S. Regression analysis when covariates are regression parameters of a random effects model for observed longitudinal measurements. Biometrics 2000, 56, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandis, R.; Teerenstra, S.; Massuger, L.; Sweep, F.; Eysbouts, Y.; IntHout, J. A tutorial on dynamic risk prediction of a binary outcome based on a longitudinal biomarker. Biom. J. 2020, 62, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, A.; Heron, J.; Smith, A.; Macdonald-Wallis, C.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Steele, F.; Tilling, K. Joint modelling compared with two stage methods for analysing longitudinal data and prospective outcomes: A simulation study of childhood growth and BP. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2017, 26, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzmaurice Garrett, M.; Nan MLaird James, H. Applied Longitudinal Analysis, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkley, G.B. Free radical-mediated reperfusion injury: A selective review. Br. J. Cancer Suppl. 1987, 8, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brini, M.; Calì, T.; Ottolini, D.; Carafoli, E. Neuronal calcium signaling: Function and dysfunction. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2787–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, D.; Freund, Y.; Marcusohn, E.; Diab, T.; Klein, E.; Raz, A.; Neuberger, A. Association Between Ionized Calcium Level and Neurological Outcome in Endovascularly Treated Patients with Spontaneous Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurocrit. Care 2021, 35, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badarni, K.; Harush, N.; Andrawus, E.; Bahouth, H.; Bar-Lavie, Y.; Raz, A.; Roimi, M.; Epstein, D. Association Between Admission Ionized Calcium Level and Neurological Outcome of Patients with Isolated Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurocrit. Care 2023, 39, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Xiao, K.; Zhao, S.; Liu, K.; Huang, F.; Xiao, H. Association between serum calcium level and the risk of acute kidney injury in ICU patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1433653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhuang, D.; Cai, S.; Ding, F.; Tian, F.; Huang, M.; Li, L.; Chen, W.; Li, K.; Sheng, J. Low serum calcium is a novel predictor of unfavorable prognosis after traumatic brain injury. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempien, A.; Katz, A.M.; Messineo, F.C. Calcium and cardiac arrest. Ann. Intern. Med. 1986, 105, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stueven, H.; Thompson, B.M.; Aprahamian, C.; Darin, J.C. Use of calcium in prehospital cardiac arrest. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1983, 12, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzenmeyer, P.; Martin, I.; d’Athis, P.; Grumbach, Y.; Delmestre, M.C.; Blondé-Cynober, F.; Derycke, B.; Brondel, L.; Club Francophone de Gériatrie et Nutrition. A new formula for correction of total calcium level into ionized serum calcium values in very elderly hospitalized patients. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2007, 45, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngquist, S.T.; Heyming, T.; Rosborough, J.P.; Niemann, J.T. Hypocalcemia following resuscitation from cardiac arrest revisited. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejersted, O.M. Calcium controls cardiac function--by all means! J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 2919–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.P.; Morgan, K.G. Calcium and cardiovascular function. Intracellular calcium levels during contraction and relaxation of mammalian cardiac and vascular smooth muscle as detected with aequorin. Am. J. Med. 1984, 77, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.L.; Smith, S.M. Calcium-Sensing Receptor: A Key Target for Extracellular Calcium Signaling in Neurons. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikor, D.; Hurła, M.; Słowikowski, B.; Szymanowicz, O.; Poszwa, J.; Banaszek, N.; Drelichowska, A.; Jagodziński, P.P.; Kozubski, W.; Dorszewska, J. Calcium Ions in the Physiology and Pathology of the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, M.; Seth, H.; Björefeldt, A.; Lyckenvik, T.; Andersson, M.; Wasling, P.; Zetterberg, H.; Hanse, E. Ionized calcium in human cerebrospinal fluid and its influence on intrinsic and synaptic excitability of hippocampal pyramidal neurons in the rat. J. Neurochem. 2019, 149, 452–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heining, M.P.; Band, D.M.; Linton, R.A. Choice of calcium salt. A comparison of the effects of calcium chloride and gluconate on plasma ionized calcium. Anaesthesia 1984, 39, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; McDonnell, E.H.; Sedor, F.A.; Toffaletti, J.G. pH effects on measurements of ionized calcium and ionized magnesium in blood. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2002, 126, 947–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thode, J.; Holmegaard, S.N.; Transbøl, I.; Fogh-Andersen, N.; Siggaard-Andersen, O. Adjusted ionized calcium (at pH 7.4) and actual ionized calcium (at actual pH) in capillary blood compared for clinical evaluation of patients with disorders of calcium metabolism. Clin. Chem. 1990, 36, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The American Heart Association in collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 6: Advanced cardiovascular life support: Section 1: Introduction to ACLS 2000: Overview of recommended changes in ACLS from the guidelines 2000 conference. Circulation 2000, 102 (Suppl. S8), I86–I89. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.H.; Couper, K.; Nix, T.; Drennan, I.; Reynolds, J.; Kleinman, M.; Berg, K.M.; Advanced Life Support and Paediatric Life Support Task Forces at the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Calcium during cardiac arrest: A systematic review. Resusc. Plus 2023, 14, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stueven, H.A.; Thompson, B.; Aprahamian, C.; Tonsfeldt, D.J.; Kastenson, E.H. The effectiveness of calcium chloride in refractory electromechanical dissociation. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1985, 14, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, A.; Foran, M.; Koyfman, A. Does calcium administration during cardiopulmonary resuscitation improve survival for patients in cardiac arrest? Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014, 64, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivin, J.R.; Gooley, T.; Zager, R.A.; Ryan, M.J. Hypocalcemia: A pervasive metabolic abnormality in the critically ill. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2001, 37, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Ni, H.; Deng, H. Predictive value of ionized calcium in critically ill patients: An analysis of a large clinical database MIMIC II. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinas-Rios, J.M.; Sanchez-Aguilar, M.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, J.J.; Gonzalez-Aguirre, D.; Heinen, C.; Meyer, F.; Kretschmer, T. Hypocalcaemia as a prognostic factor of early mortality in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Neurol. Res. 2014, 36, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Hamano, T.; Doi, Y.; Oka, T.; Kajimoto, S.; Kubota, K.; Yasuda, S.; Shimada, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Hashimoto, N.; et al. Hidden Hypocalcemia as a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality among Patients Undergoing Incident Hemodialysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, P.; Scheidegger, D.; Buchmann, B.; Barth, D. Cardiac arrest and blood ionized calcium levels. Ann. Intern. Med. 1988, 109, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Jung, Y.H.; Jeung, K.W.; Lee, B.K.; Youn, C.S.; Mamadjonov, N.; Kim, J.W.; Heo, T.; Min, Y.I. Ion shift index as a promising prognostic indicator in adult patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2019, 137, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Neurological Outcome at 30 Days | 30-Day Mortality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favorable (n = 181, 42.9%) | Unfavorable (n = 240, 57.1%) | p-Value | Survived (n = 263, 62.5%) | Dead (n = 158, 37.5%) | p-Value | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age, years | 56.4 ± 16.0 | 59.2 ± 17.1 | 0.089 | 56.5 ± 16.4 | 60.5 ± 16.9 | 0.017 |

| Male, n (%) | 152 (84.0%) | 161 (67.1%) | <0.001 | 206 (78.3%) | 107 (67.7%) | 0.022 |

| Cardiac arrest information | ||||||

| Witnessed, n (%) | 137 (75.7%) | 148 (61.7%) | 0.003 | 195 (74.1%) | 90 (57.0%) | <0.001 |

| Bystander, n (%) | 140 (77.3%) | 149 (62.1%) | 0.001 | 190 (72.2%) | 99 (62.7%) | 0.052 |

| Non-cardiac cause, n (%) | 146 (80.7%) | 97 (40.4%) | <0.001 | 177 (67.3%) | 66 (41.8%) | <0.001 |

| Initial rhythm, shockable (VF/VT), n (%) | 114 (63.0%) | 52 (21.7%) | <0.001 | 136 (51.7%) | 30 (19.0%) | <0.001 |

| Defibrillation, n (%) | 72 (40.0%) | 47 (19.6%) | <0.001 | 87 (33.2%) | 32 (20.3%) | <0.001 |

| Total dose of epinephrine, mg | 1.6 ± 2.8 | 2.8 ± 3.1 | <0.001 | 1.9 ± 2.8 | 2.9 ± 3.3 | 0.001 |

| Time from collapse to ROSC, mins | 21.1 ± 17.3 | 33.5 ± 18.5 | <0.001 | 24.0 ± 17.6 | 35.2 ± 19.3 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 63 (34.8%) | 96 (40.0%) | 0.324 | 89 (33.8%) | 70 (44.3%) | 0.041 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (16.6%) | 70 (29.2%) | 0.004 | 54 (20.5%) | 46 (29.1%) | 0.059 |

| Coronary artery disease | 52 (28.7%) | 45 (18.8%) | 0.022 | 62 (23.6%) | 35 (22.2%) | 0.829 |

| Pulmonary disease | 12 (6.6%) | 24 (10.0%) | 0.295 | 24 (9.1%) | 12 (7.6%) | 0.716 |

| Renal disease | 10 (5.5%) | 46 (19.2%) | <0.001 | 20 (7.6%) | 36 (22.8%) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 13 (7.2%) | 22 (9.2%) | 0.581 | 15 (5.7%) | 20 (12.7%) | 0.02 |

| Cardiac failure | 79 (43.6%) | 153 (63.8%) | <0.001 | 123 (46.8%) | 109 (69.0%) | <0.001 |

| Hospital care | ||||||

| CRRT | 12 (6.6%) | 68 (28.3%) | <0.001 | 24 (9.1%) | 56 (35.4%) | <0.001 |

| ECMO | 21 (11.6%) | 20 (8.3%) | 0.34 | 28 (10.6%) | 13 (8.2%) | 0.522 |

| Adjusted ionized calcium level, mg/dL | ||||||

| 0 h after ROSC | 1.02 ± 0.12 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 0.91 ± 0.11 | <0.001 |

| 12 h after ROSC | 1.15 ± 0.08 | 1.06 ± 0.11 | <0.001 | 1.13 ± 0.09 | 1.06 ± 0.12 | <0.001 |

| 24 h after ROSC | 1.18 ± 0.07 | 1.11 ± 0.10 | <0.001 | 1.16 ± 0.08 | 1.11 ± 0.11 | <0.001 |

| 48 h after ROSC | 1.19 ± 0.07 | 1.14 ± 0.10 | <0.001 | 1.18 ± 0.08 | 1.14 ± 0.11 | 0.001 |

| 72 h after ROSC | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 1.18 ± 0.10 | 0.003 | 1.20 ± 0.07 | 1.18 ± 0.10 | 0.086 |

| Calcium infusion, yes | 176 (97.2%) | 207 (86.2%) | <0.001 | 247 (93.9%) | 136 (86.1%) | 0.011 |

| Calcium infusion, total dose, mg | 3329.8 ± 2140.8 | 1812.1 ± 1485.9 | <0.001 | 2846.0 ± 2136.5 | 1829.8 ± 1364.9 | <0.001 |

| Neurological Outcome at 30 Days | 30-Day Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC Goodness-Of-Fit | AUC (95% CI) | AIC Goodness-Of-Fit | AUC (95% CI) | |

| Excluding Ca2+ level and calcium infusion variables | 427.35 | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | 469.70 | 0.78 (0.74–0.83) |

| Ca2+ at 0 h | 403.09 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | 457.08 | 0.80 (0.75–0.84) |

| Ca2+ at 12 h (corrected for 0–12 h infusion) | 367.19 | 0.88 (0.84–0.91) | 424.79 | 0.81 (0.77–0.86) |

| Ca2+ at 24 h (corrected for 12–24 h infusion) | 379.83 | 0.87 (0.84–0.91) | 445.75 | 0.80 (0.76–0.84) |

| Ca2+ at 48 h (corrected for 24–48 h infusion) | 362.87 | 0.88 (0.85–0.92) | 432.84 | 0.80 (0.77–0.85) |

| Ca2+ at 72 h (corrected for 48–72 h infusion) | 386.58 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | 425.76 | 0.80 (0.75–0.84) |

| Neurological Outcome at 30 Days | 30-Day Mortality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Initial rhythm | 0.16 (0.11–0.25) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.28–1.00) | 0.049 | 0.22 (0.14–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.43 (0.23–0.82) | 0.010 |

| Time-to-ROSC | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <0.001 |

| Non-cardiac cause | 0.16 (0.10–0.25) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.21–0.85) | 0.016 | 0.35 (0.23–0.52) | <0.001 | 1.20 (0.64–2.27) | 0.577 |

| History of renal disease | 4.05 (2.06–8.74) | <0.001 | 3.52 (1.41–9.50) | 0.009 | 3.59 (2.01–6.56) | <0.001 | 3.93 (1.96–8.13) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 2.57 (1.61–4.21) | <0.001 | 2.78 (1.37–5.76) | 0.005 | 1.72 (1.10–2.69) | 0.016 | ||

| Witnessed | 0.52 (0.34–0.79) | 0.002 | 0.75 (0.39–1.41) | 0.365 | 0.46 (0.30–0.70) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.37–1.04) | 0.070 |

| Baseline Ca2+ | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.76–0.90) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.84–0.96) | 0.001 |

| Rate of change in Ca2+ | 1.49 (1.32–1.69) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.78–1.38) | 0.805 | 1.36 (1.22–1.53) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.82–1.27) | 0.873 |

| Total calcium infusion dose | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | <0.001 |

| Models | Neurological Outcome at 30 Days | 30-Day Mortality | Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (95% CI) | p-Value | AUC (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| 1. Excluding calcium-related variables | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.74–0.83) | 0.012 | Model 1 vs. 2 |

| 2. Neurological outcome: Ca2+ at 48 h (corrected for 24–48 h infusion) Mortality outcome: Ca2+ at 12 h (corrected for 0–12 h infusion) | 0.88 (0.85–0.92) | 0.005 | 0.82 (0.77–0.86) | 0.124 | Model 2 vs. 3 |

| 3. Baseline Ca2+ and slope over time (corrected for cumulative infusion) | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | 0.001 | Model 1 vs. 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S.Y.; Zhang, H.-S.; Park, I.; You, J.S.; Park, Y.S. Association Between Serum Ionized Calcium Levels and Neurological Outcomes in Patients with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Life 2025, 15, 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121889

Park SY, Zhang H-S, Park I, You JS, Park YS. Association Between Serum Ionized Calcium Levels and Neurological Outcomes in Patients with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Life. 2025; 15(12):1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121889

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Shin Young, Hyun-Soo Zhang, Incheol Park, Je Sung You, and Yoo Seok Park. 2025. "Association Between Serum Ionized Calcium Levels and Neurological Outcomes in Patients with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest" Life 15, no. 12: 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121889

APA StylePark, S. Y., Zhang, H.-S., Park, I., You, J. S., & Park, Y. S. (2025). Association Between Serum Ionized Calcium Levels and Neurological Outcomes in Patients with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Life, 15(12), 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121889