Functional Characterization of OsWRKY7, a Novel WRKY Transcription Factor in Rice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of OsWRKY7

2.2. Bioinformatic Analysis of OsWRKY7

2.3. Subcellular Localization Prediction

2.4. Analysis of Conserved Motifs and Domains in Rice WRKY Proteins

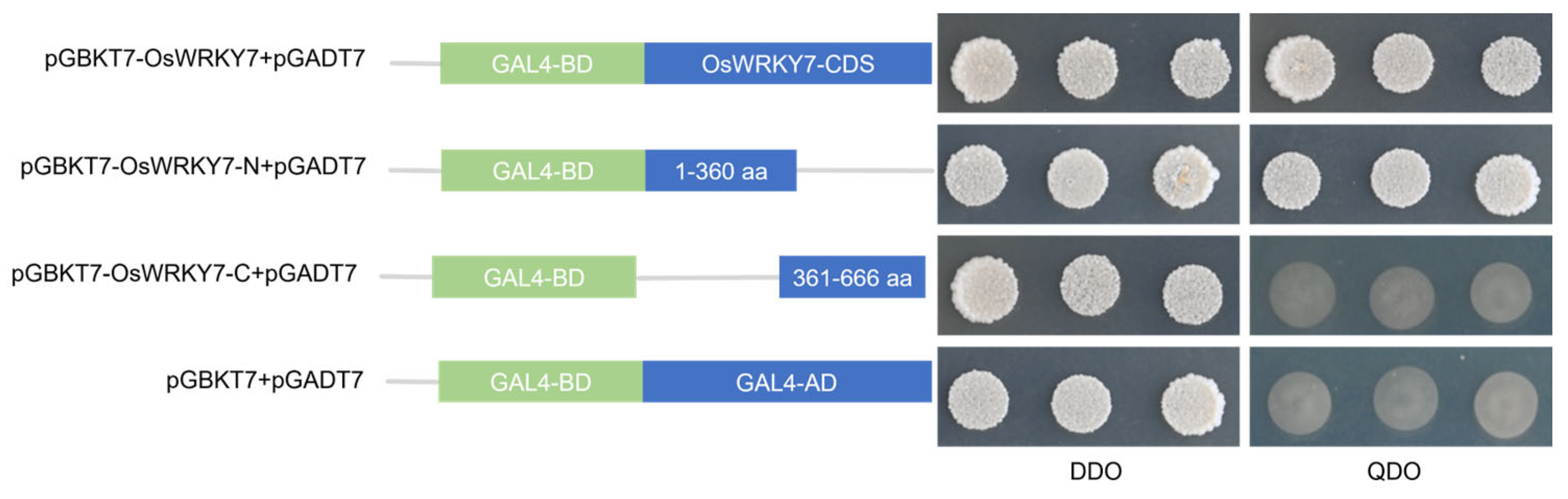

2.5. Analysis of the Transcriptional Activation Activity of OsWRKY7

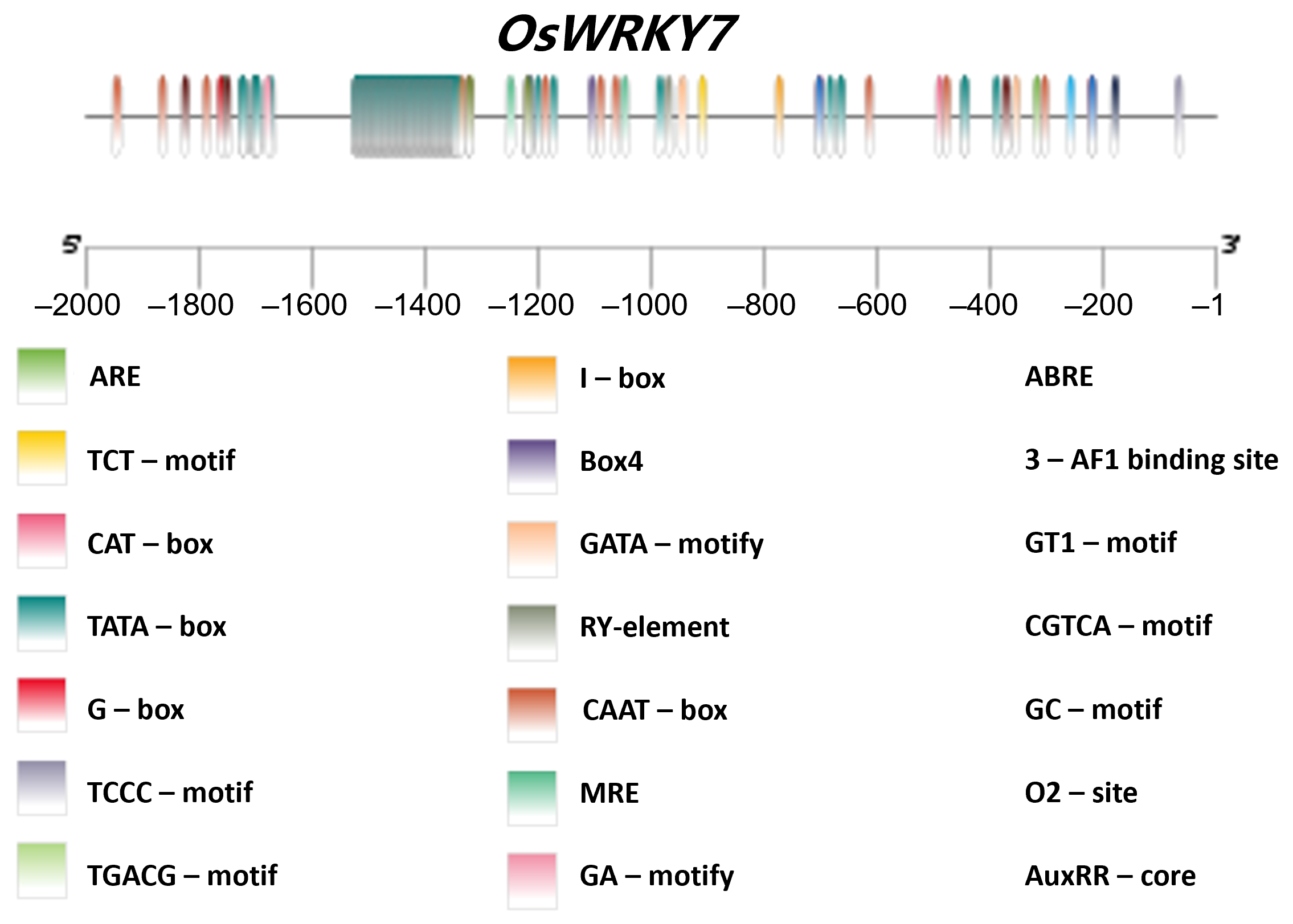

2.6. Analysis of Promoter Cis-Element and Haplotype

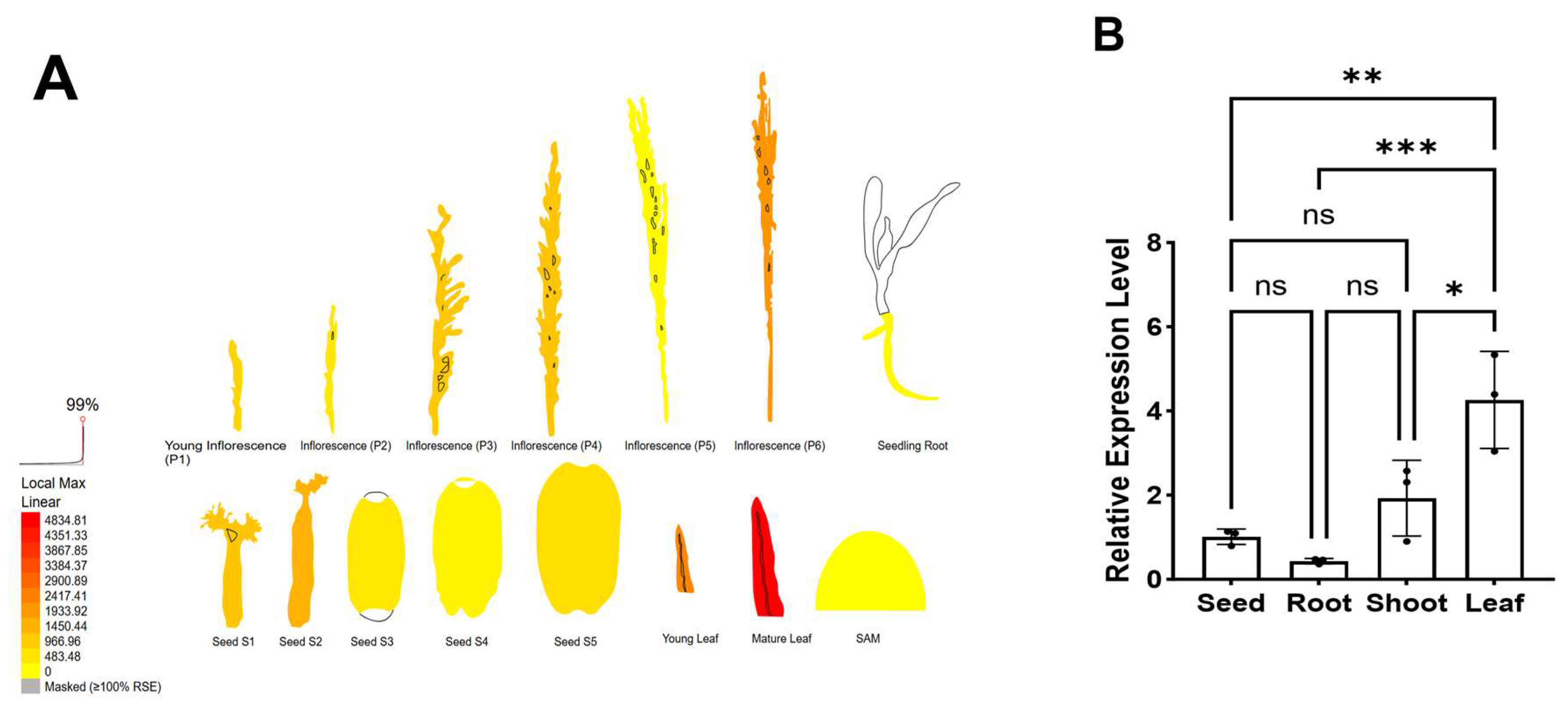

2.7. Analysis of OsWRKY7 Expression Characteristics

2.8. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of WRKY7 Structural Conservation

3.2. Physicochemical Properties and Structural Analysis of the OsWRKY7 Encoding Protein

3.3. Structural Characteristics of the WRKY Protein Family Domains and Genes in Rice

3.4. Transcriptional Activation Analyses of OsWRKY7

3.5. Analysis of OsWRKY7’s Promoter Elements and Haplotype

3.6. The Expression Patterns of OsWRKY7 in Different Tissues

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Odorico, P.; Carr, J.A.; Laio, F.; Ridolfi, L.; Vandoni, S. Feeding Humanity Through Global Food Trade. Earth’s Future 2014, 2, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Transcriptome and Hormonal Analyses Reveal an Important Role of Auxin and Cytokinin in Regulating Rice Ratooning Ability. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Transcription Factor OsbZIP10 Modulates Rice Grain Quality by Regulating OsGIF1. Plant J. 2024, 119, 2181–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eulgem, T.; Rushton, P.J.; Robatzek, S.; Somssich, I.E. The WRKY Superfamily of Plant Transcription Factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, R. An Alanine to Valine Mutation of Glutamyl-tRNA Reductase Enhances 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Synthesis in Rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 2817–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Yang, H. Role of Serotonin in Plant Stress Responses: Quo Vadis? J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1706–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eulgem, T.; Somssich, I.E. Networks of WRKY Transcription Factors in Defense Signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, T. Melatonin Activates the OsbZIP79-OsABI5 Module that Orchestrates Nitrogen and ROS Homeostasis to Alleviate Nitrogen-Limitation Stress in Rice. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K. OsbZIP83-OsCOMT15 Module Confers Melatonin-Ameliorated Cold Tolerance in Rice. Plant J. 2025, 123, e70402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, Z.L.; Zou, X.; Huang, J.; Ruas, P.; Thompson, D.; Shen, Q.J. Annotations and Functional Analyses of the Rice WRKY Gene Superfamily Reveal Positive and Negative Regulators of Abscisic Acid Signaling in Aleurone Cells. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, P.J.; Somssich, I.E.; Ringler, P.; Shen, Q.J. WRKY Transcription Factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, K.; Kigawa, T.; Inoue, M.; Tateno, M.; Yamasaki, T.; Yabuki, T.; Aoki, M.; Seki, E.; Matsuda, T.; Nunokawa, E.; et al. Structural Basis for Sequence-specific DNA Recognition by an Arabidopsis WRKY Transcription Factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 7683–7691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhatterwal, P.; Basu, S.; Mehrotra, S.; Mehrotra, R. Genome Wide Analysis of W-box Element in Arabidopsis thaliana Reveals TGAC Motif with Genes Down Regulated by Heat and Salinity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Peng, X.; Niu, X.; Fei, Z.; Cao, S.; Liu, Y. Genome-wide Analysis of WRKY Transcription Factors in Solanum lycopersicum. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2012, 287, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, J. WRKY Transcription Factors in Rice: Key Regulators Orchestrating Development and Stress Resilience. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 8388–8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Ren, F.; Liu, Q.; Chen, L.; Pang, Y.; Zhao, F. WRKY Transcription Factors: Hubs for Regulating Plant Growth and Stress Responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, S.; Ye, N.; Jiang, M.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J. WRKY Transcription Factors in Plant Responses to Stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2017, 59, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, S. Genome-wide Association Studies Identify OsWRKY53 as a Key Regulator of Salt Tolerance in Rice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, F.; Liu, H.; Xie, Q.; Dai, S.; et al. WRKY53 Negatively Regulates Rice Cold Tolerance at the Booting Stage by Fine-tuning Anther Gibberellin Levels. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4495–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, J.; Baek, D.; Park, H.C.; Kim, J.K. Functional Analysis of a Cold-responsive Rice WRKY Gene, OsWRKY71. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 10, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokotani, N.; Sato, Y.; Tanabe, S.; Chujo, T.; Shimizu, T.; Okada, K.; Yamane, H.; Shimono, M.; Sugano, S.; Takatsuji, H.; et al. WRKY76 is a Rice Transcriptional Repressor Playing Opposite Roles in Blast Disease Resistance and Cold Stress Tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5085–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S. The OsWRKY63-OsWRKY76-OsDREB1B Module Regulates Chilling Tolerance in Rice. Plant J. 2022, 112, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shiroto, Y.; Kishitani, S.; Ito, Y.; Toriyama, K. Enhanced Heat and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Rice Seedlings Overexpressing OsWRKY11 under the Control of HSP101 Promoter. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Kwon, C.T.; Kim, S.H.; Shim, Y.; Lim, C.; Koh, H.J.; An, G.; Kang, K. OsWRKY114 Negatively Regulates Drought Tolerance by Restricting Stomatal Closure in Rice. Plants 2022, 11, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Kang, K.; Kim, S.H.; An, G.; Paek, N.C. OsWRKY5 Promotes Rice Leaf Senescence via Senescence-Associated NAC and Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Wu, T.; Ma, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Bian, M.; Bai, H.; Huang, W.; Liu, H.; et al. Rice Transcription Factor OsWRKY55 Is Involved in the Drought Response and Regulation of Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Fang, H.; Peng, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Li, Z.; et al. The WRKY Transcription Factor OsWRKY54 Is Involved in Salt Tolerance in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Qin, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; et al. OsWRKY70 Plays Opposite Roles in Blast Resistance and Cold Stress Tolerance in Rice. Rice 2024, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Yin, J.; Zhang, H.; Asif, M.H.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. The WRKY10-VQ8 Module Safely and Effectively Regulates Rice Thermotolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2126–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Q.J. The WRKY Gene Family in Rice (Oryza sativa). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting Transmembrane Protein Topology with a Hidden Markov Model: Application to Complete Genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Pedersen, M.D.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Marcatili, P.; Nielsen, H.; Krogh, A.; Winther, O. DeepTMHMM Predicts Alpha and Beta Transmembrane Proteins Using Deep Neural Networks. BioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, N.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Gupta, R.; Gammeltoft, S.; Brunak, S. Prediction of Post-translational Glycosylation and Phosphorylation of Proteins from the Amino Acid Sequence. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.S.; Lin, C.J.; Hwang, J.K. Predicting Subcellular Localization of Proteins for Gram-negative Bacteria by Support Vector Machines Based on n-peptide Compositions. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Elkan, C. Fitting a Mixture Model by Expectation Maximization to Discover Motifs in Biopolymers. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology, Stanford, CA, USA, 14–17 August 1994; AAAI Press: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The Conserved Domain Database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, Y.; de la Bastide, M.; Hamilton, J.P.; Kanamori, H.; McCombie, W.R.; Ouyang, S.; Schwartz, D.C.; Tanaka, T.; Wu, J.; Zhou, S.; et al. Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare Reference Genome Using Next Generation Sequence and Optical Map Data. Rice 2013, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, C.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Yu, W.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, J.; Shen, L. OsNAC5 Orchestrates OsABI5 to Fine-tune Cold Tolerance in Rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 660–682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rombauts, S.; Déhais, P.; Van Montagu, M.; Rouzé, P. PlantCARE, a Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Element Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shang, L.; He, W.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; et al. A Complete Assembly of the Rice Nipponbare Reference Genome. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Qin, G.; Xia, C.; Xu, X.; Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ming, L.; Chen, L.L.; et al. An Inferred Functional Impact Map of Genetic Variants in Rice. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1584–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Ma, D.; Li, F.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, T.; et al. Evolution of Different Rice Ecotypes and Genetic Basis of Flooding Adaptability in Deepwater Rice by GWAS. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.C.; Fry, B.; Maller, J.; Daly, M.J. Haploview: Analysis and Visualization of LD and Haplotype Maps. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Nijhawan, A.; Arora, R.; Agarwal, P.; Ray, S.; Sharma, P.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. F-Box Proteins in Rice. Genome-Wide Analysis, Classification, Temporal and Spatial Gene Expression During Panicle and Seed Development, and Regulation by Light and Abiotic Stress. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1467–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, D.; Vinegar, B.; Nahal, H.; Ammar, R.; Wilson, G.V.; Provart, N.J. An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” Browser for Exploring and Analyzing Large-scale Biological Data Sets. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e718. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qin, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, S. Expression Identification of Three OsWRKY Genes in Response to Abiotic Stress and Hormone Treatments in Rice. Plant Signal. Behav. 2023, 18, 2292844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Kou, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S. OsWRKY45 Alleles Play Different Roles in Abscisic Acid Signalling and Salt Stress Tolerance but Similar Roles in Drought and Cold Tolerance in Rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4863–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Functional Study of OsWRKY95 in Regulating Drought Tolerance in Rice. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, H.X. Preliminary Study on the Molecular Mechanism of OsWRKY53 Regulating Plant Type and Grain Shape in Rice. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.Y. Functional Study of OsWRKY26 Gene in Regulating Resistance to Bacterial Blight in Rice. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Y.; Yoshida, R.; Kishi-Kaboshi, M.; Matsushita, A.; Jiang, C.J.; Goto, S.; Takahashi, A.; Hirochika, H.; Takatsuji, H. Abiotic Stresses Antagonize the Rice Defence Pathway through the Tyrosine-dephosphorylation of OsMPK6. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, L.; Tong, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J. SAPK10-mediated Phosphorylation on WRKY72 Releases Its Suppression on Jasmonic Acid Biosynthesis and Bacterial Blight Resistance. iScience 2019, 16, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. OsMKKK70 Regulates Grain Size and Leaf Angle in Rice through the OsMKK4-OsMAPK6-OsWRKY53 Signaling Pathway. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 2043–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Tong, H.; Fang, J.; Bu, Q. Transcription Factor OsWRKY53 Positively Regulates Brassinosteroid Signaling and Plant Architecture. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, X.; Xiao, H.; Peng, Y.; Xia, X.; Wang, X. Nitrogen deficiency modulates carbon allocation to promote nodule nitrogen fixation capacity in soybean. Exploration 2023, 4, 20230104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yan, N.; Bai, H.; Kwok, R.T.K.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission luminogens for augmented photosynthesis. Exploration 2022, 2, 20210053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; He, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Shou, H.; Zheng, L. OsbHLH062 regulates iron homeostasis by inhibiting iron deficiency responses in rice. aBIOTECH 2025, 6, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Wang, H.; Zhong, Z.; Li, S.; Qin, P. Emerging Strategies to Improve Heat Stress Tolerance in Crops. aBIOTECH 2025, 6, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cao, H.; Qin, W.; Yang, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, L.; Song, H.; Zhang, Q. Genomic and Modern Biotechnological Strategies for Enhancing Salt Tolerance in Crops. New Crops 2024, 2, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jin, W. Molecular Underpinnings of Plant Stress Granule Dynamics in Response to High-Temperature Stress. New Crops 2025, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeky, C.; Khushbu, K.; Deepak, K.J.; Mrunmay, K.G.; Nrisingha, D. Pearl millet WRKY transcription factor PgWRKY52 positively regulates salt stress tolerance through ABA-MeJA mediated transcriptional regulation. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100814. [Google Scholar]

- Sindho, W.; Maqsood, A.; Muneer, A.K.; Intikhab, A.; Khuzin, D.; Amjad, H.; Nazir, A.B.; Hakim, M.; Fen, L. Deciphering the role of WRKY transcription factors in plant resilience to alkaline salt stress. Plant Stress 2024, 13, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, Y.; Si, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, C.; Liu, B.; Zheng, C.; Tan, Y.; Shu, Q.; Jiang, M. Functional Characterization of OsWRKY7, a Novel WRKY Transcription Factor in Rice. Life 2025, 15, 1852. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121852

Wei Y, Si Z, Zhang H, Hu C, Liu B, Zheng C, Tan Y, Shu Q, Jiang M. Functional Characterization of OsWRKY7, a Novel WRKY Transcription Factor in Rice. Life. 2025; 15(12):1852. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121852

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Yuting, Zhengyu Si, Haozhe Zhang, Can Hu, Bo Liu, Chenfan Zheng, Yuanyuan Tan, Qingyao Shu, and Meng Jiang. 2025. "Functional Characterization of OsWRKY7, a Novel WRKY Transcription Factor in Rice" Life 15, no. 12: 1852. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121852

APA StyleWei, Y., Si, Z., Zhang, H., Hu, C., Liu, B., Zheng, C., Tan, Y., Shu, Q., & Jiang, M. (2025). Functional Characterization of OsWRKY7, a Novel WRKY Transcription Factor in Rice. Life, 15(12), 1852. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121852