Genome-Wide Identification and Abiotic Stress-Responsive Expression Analysis of the SOS1 Gene Family in Gossypium hirsutum L.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of GhSOS1 Proteins from G. hirsutum

2.2. Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction and Selection Pressure Analysis

2.3. Gene Structure and Motif Analysis

2.4. Physicochemical Properties, Subcellular Localization, and Chromosomal Distribution

2.5. AlphaFold2 Structural Predictions and DALI Structural Alignments

2.6. Prediction of Phosphorylation Sites and Transmembrane Domains

2.7. Cis-Regulatory Element Analysis

2.8. In Silico Expression Profiling and Candidate Gene Selection

2.9. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.10. Gene Expression Analysis (qRT-PCR) of GhSOS1

3. Results

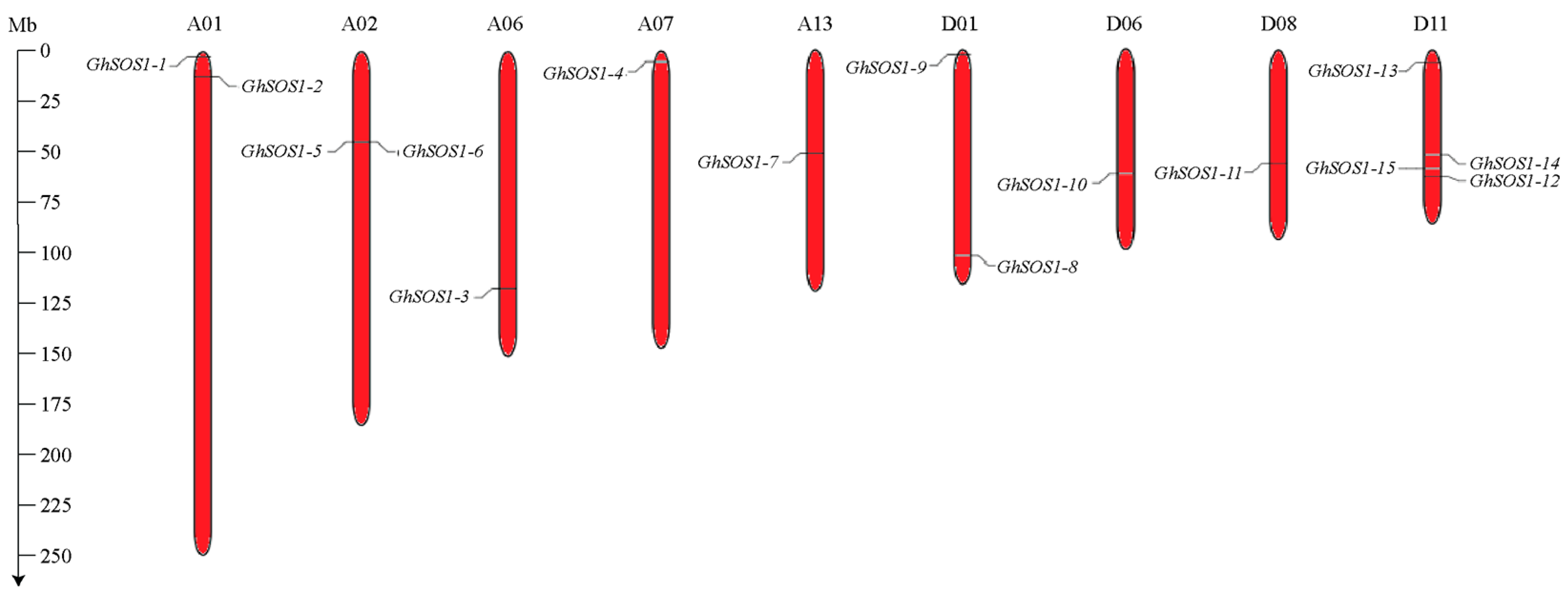

3.1. Identification of GhSOS1 Genes and Their Chromosomal Distribution

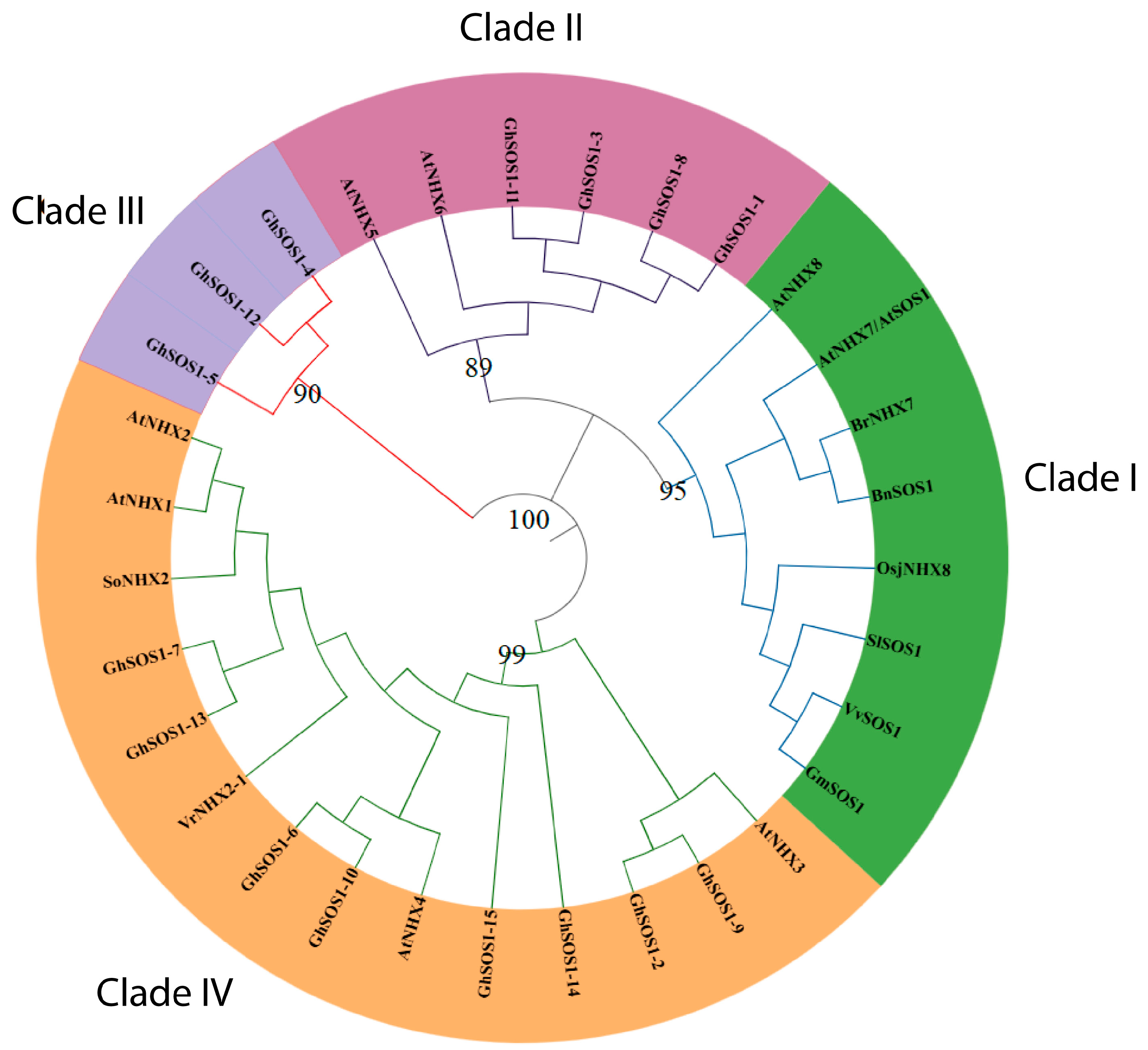

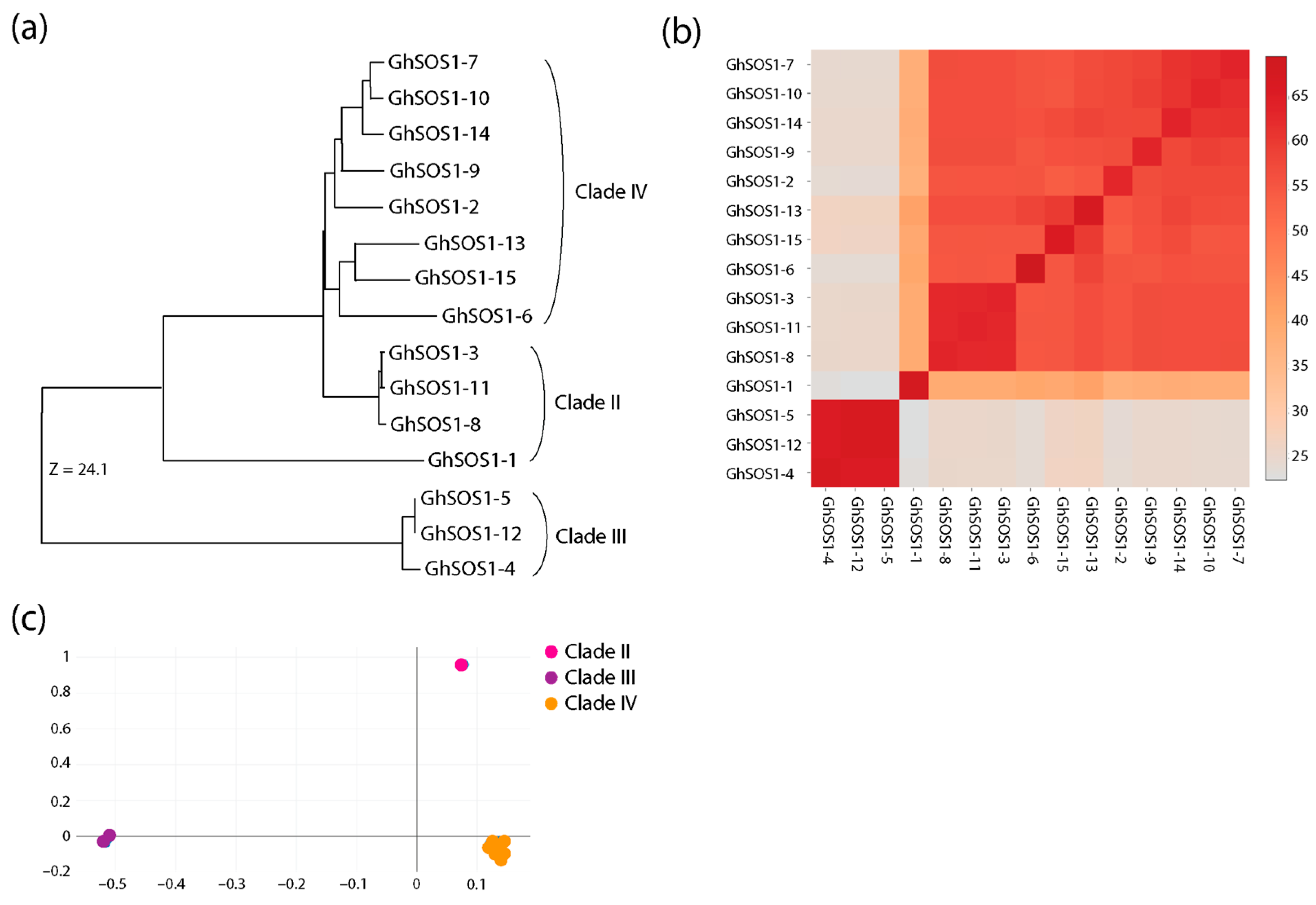

3.2. Phylogenetic Reconstructions and Selection Pressure Analysis

3.3. Analysis of Conserved Domains, Motifs, and Gene Structures

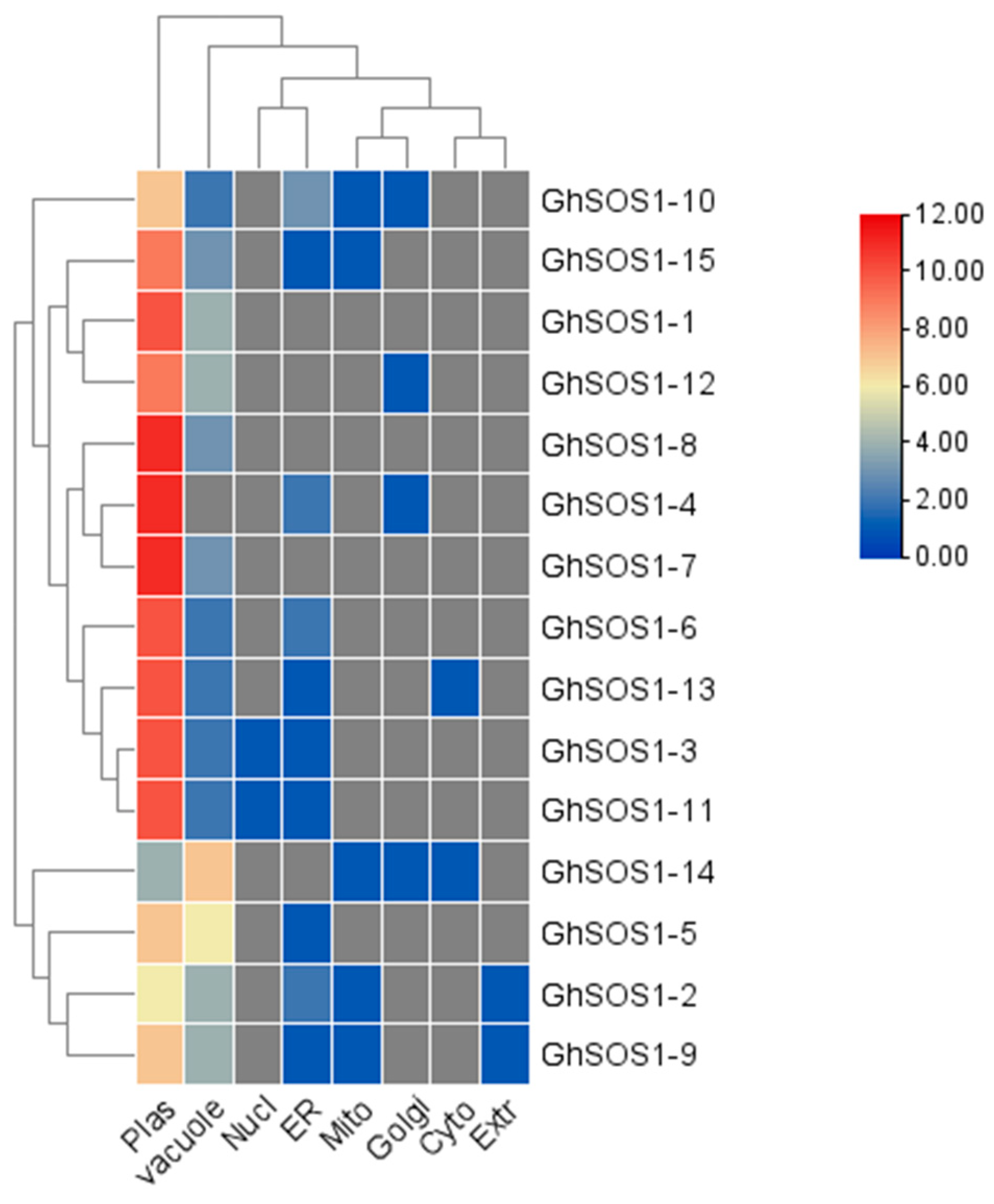

3.4. Physicochemical Properties and Protein Sub-Cellular Localization

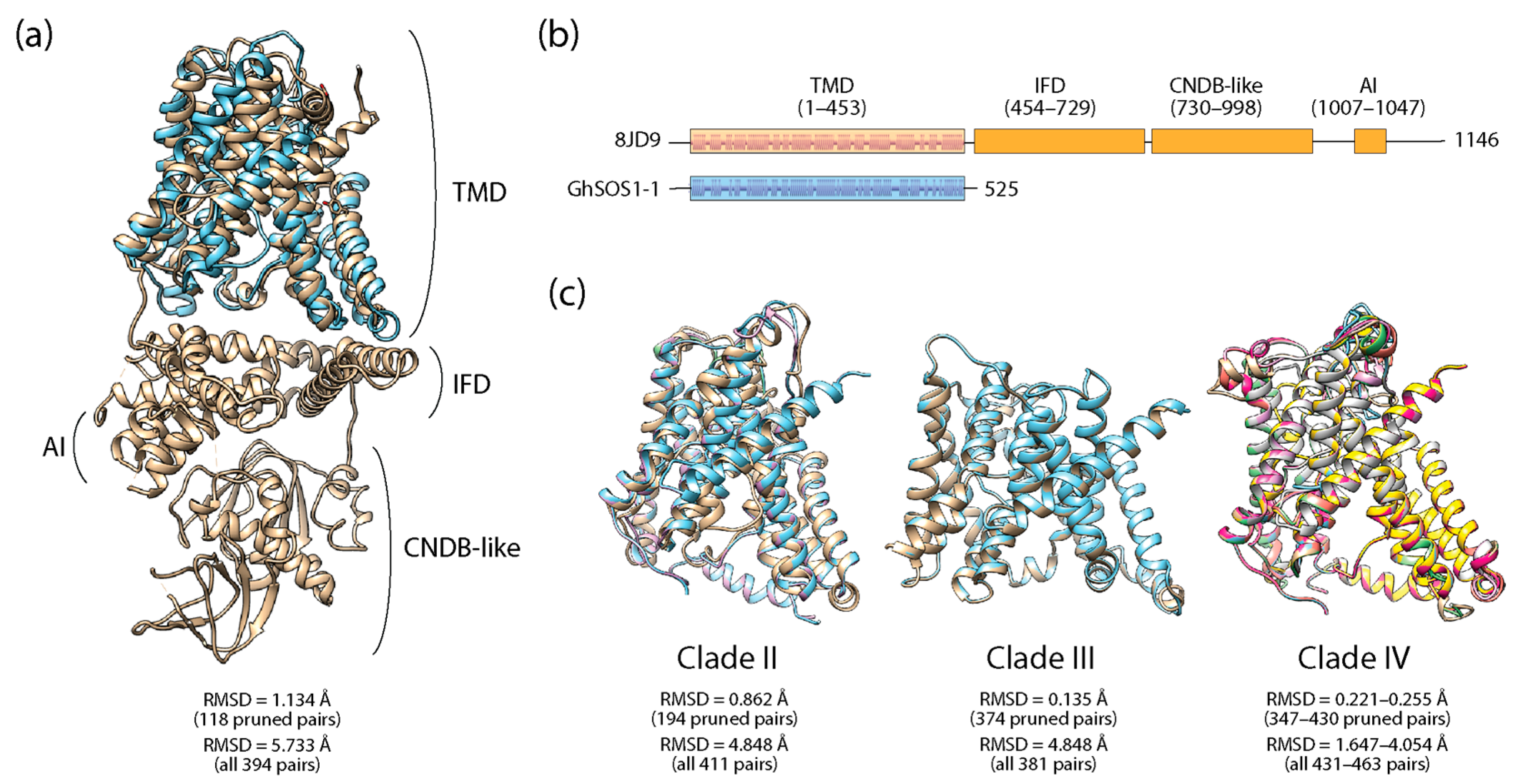

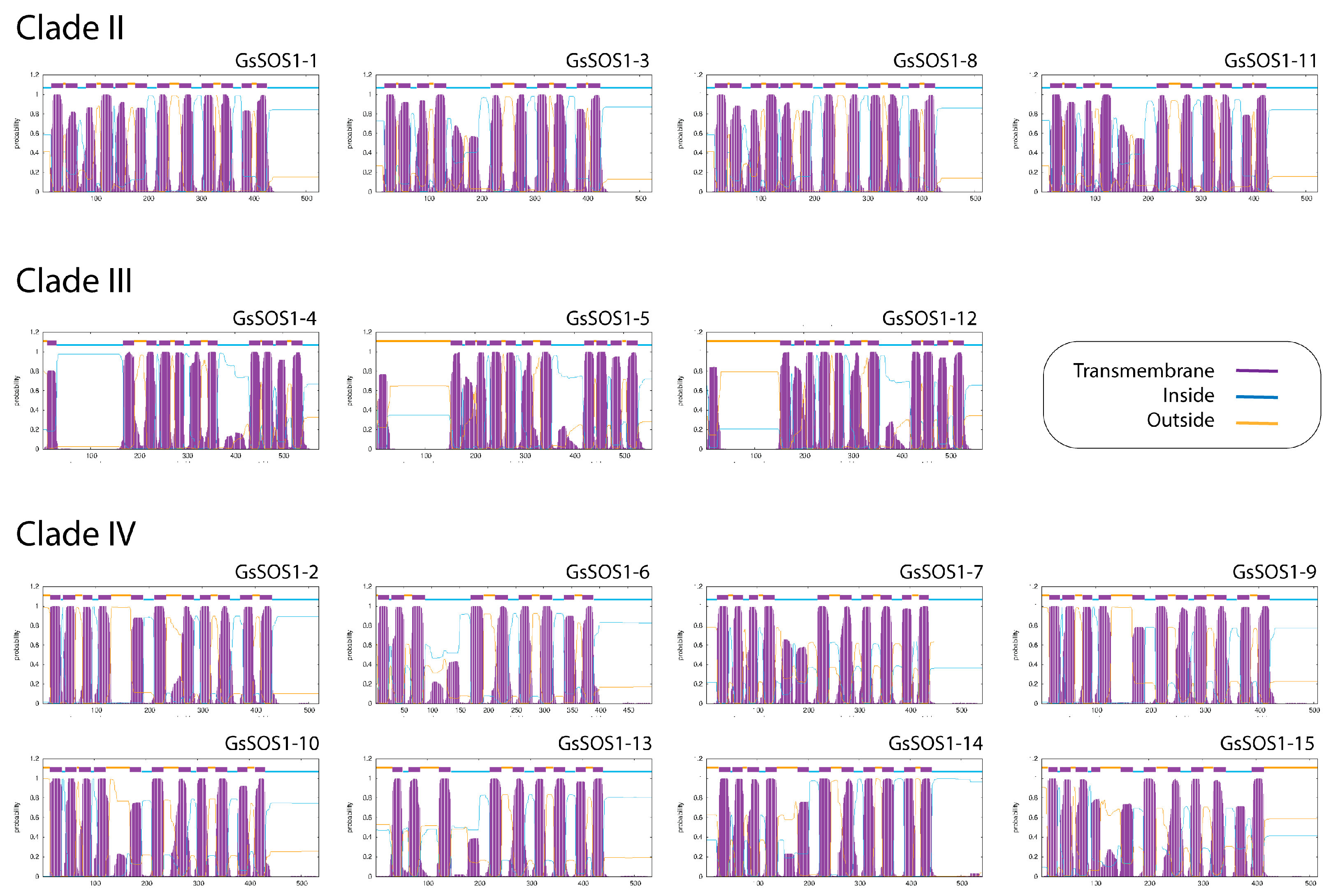

3.5. Structural Predictions, Transmembrane Topologies, and DALI Structural Alignments

3.6. Prediction of Phosphorylation Sites

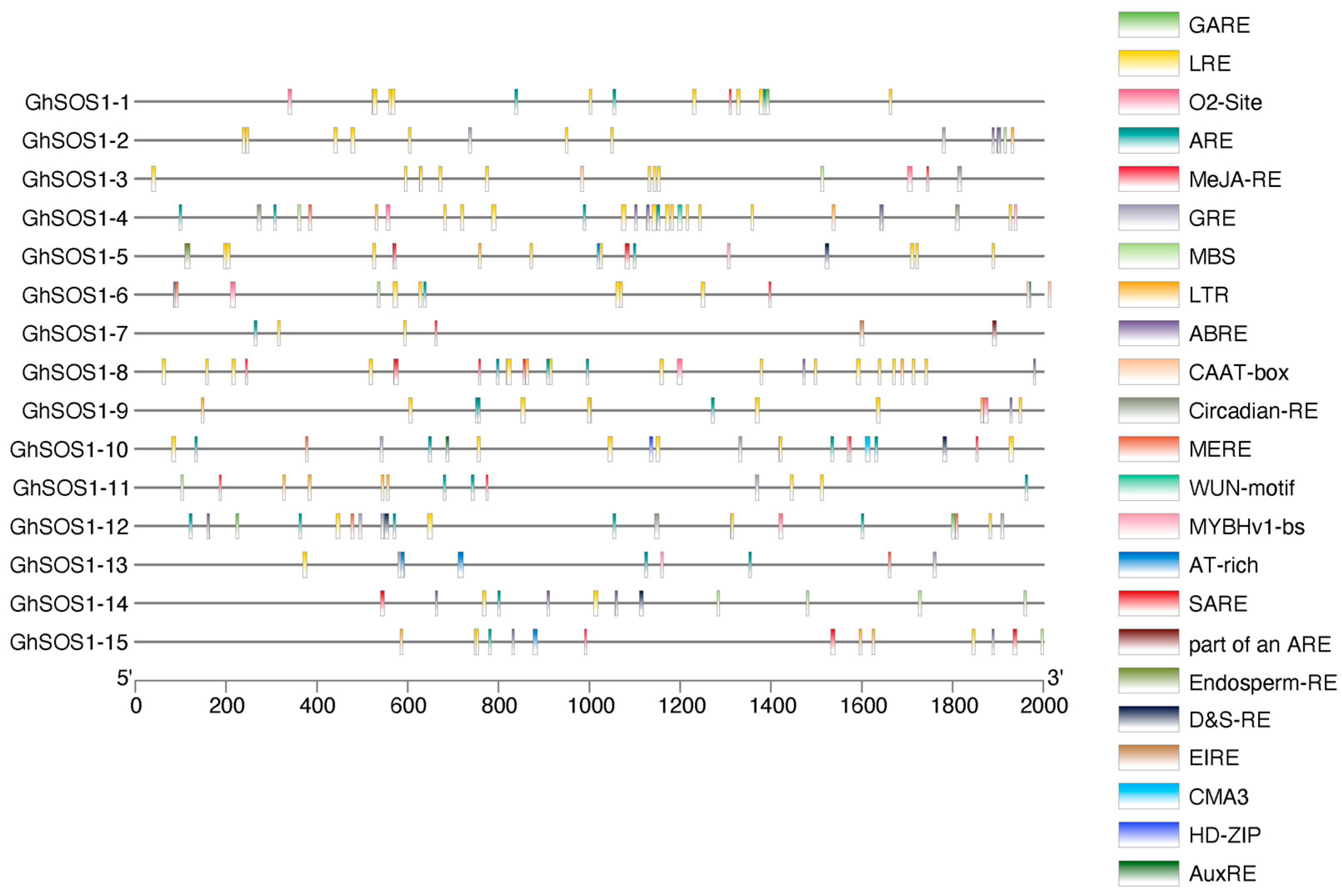

3.7. Promoter Region Analysis and Cis-Regulatory Elements

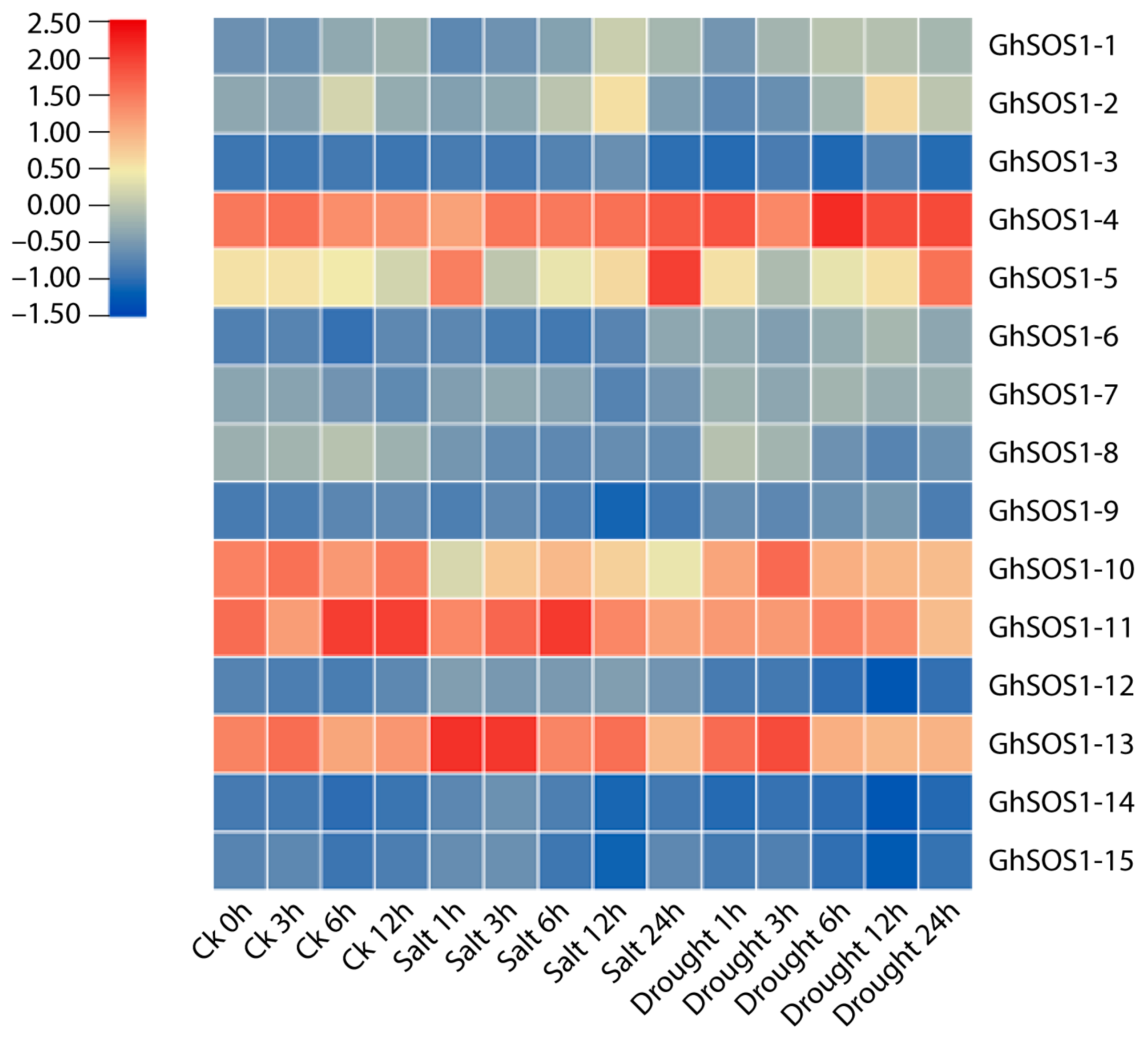

3.8. In Silico Expression Profiling and Candidate Gene Selection

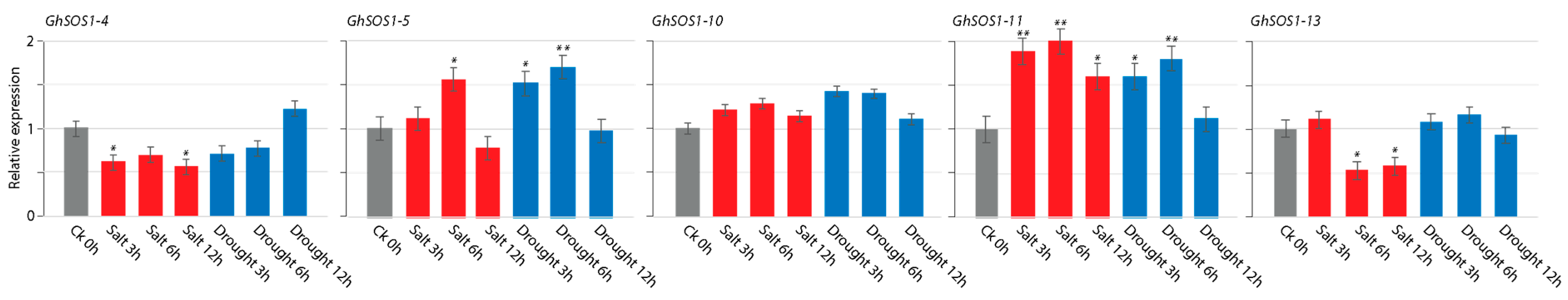

3.9. Gene Expression Analysis (qRT-PCR) of GhSOS1 Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, M.; Pan, M.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Qiao, S.; Ma, C.; Mu, H.; Zhao, W.; Guo, J. Plant survival strategies under heterogeneous salt stress: Remodeling of root architecture, ion dynamic balance, and coordination of metabolic homeostasis. Plant Soil 2025, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, C.; Li, X.; Wu, K.; Lin, M.; Sun, W. Integrated analysis of physiological responses and transcriptome of cotton seedlings under drought stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checkani, O.; Faghani, E.; Dadashi, M.R.; Nourouzi, H.A.; Sohrabi, B. Memory of water stress in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.): Evaluating physiological responses and yield stability. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Allah, S.; Rehman, A.; Hussain, M.; Farooq, M. Fiber yield and quality in cotton under drought: Effects and management. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 106994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant defense system in plants: Reactive oxygen species production, signaling, and scavenging during abiotic stress-induced oxidative damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Xiao, J.; Dong, Q.; Li, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Wu, J. Effects of drought on non-structural carbohydrates and C, N, and P stoichiometric characteristics of Pinus yunnanensis seedlings. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Dong, Q.; Luo, T.; Zhang, X.; Song, M.; Wang, X.; Ma, X. New developments in understanding cotton’s physiological and molecular responses to salt stress. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, L.M.; Moursy, M.A.; Kamal, R.; Tarboush, I.M.; Kassab, M.F.; El-Ssawy, W. Assessment of agricultural soil integrity and crop quality following multiple years of flood and modern irrigation systems. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2025, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.; Bhat, M.A.; Kumar, A.; Wani, M.A.; Bhat, F.A.; Kanth, R.H.; Shikari, A.B.; Bano, H.; Manzoor, T.; Altaf, H.; et al. Plants response to different abiotic stresses. J. Crop Health 2025, 77, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, I.; Aleem, S.; Farooq, J.; Rizwan, M.; Younas, A.; Sarwar, G.; Chohan, S.M. Salinity stress in cotton: Effects, mechanism of tolerance and its management strategies. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2019, 25, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqra, L.; Prem, A.; Sana, K.; Afzal, K.; Saher, M.; Akhtar, T.; Anjum, H.S.; Rasool, M.G.; Khalil, R.; Hameed, S.; et al. Effect of salt on different morphological traits in wheat varieties. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2021, 16, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ayars, J.E.; Corwin, D.L. Salinity management. In Microirrigation for Crop Production; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Plant responses and tolerance to salt stress: Physiological and molecular interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Wang, X.-S.; Guo, H.-D.; Bai, S.-Y.; Khan, A.; Wang, X.-M.; Gao, Y.-M.; Li, J.-S. Tomato salt tolerance mechanisms and their potential applications for fighting salinity: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 949541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Shen, L.; Han, X.; He, G.; Fan, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jin, W.; et al. Phosphatidic acid–regulated SOS2 controls sodium and potassium homeostasis in Arabidopsis under salt stress. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryum, Z.; Luqman, T.; Nadeem, S.; Khan, S.M.U.D.; Wang, B.; Ditta, A.; Khan, M.K.R. An overview of salinity stress, mechanism of salinity tolerance and strategies for its management in cotton. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 907937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, N.; Yu, Q.; Wang, H. Genome-wide characterization of salt-responsive miRNAs, circRNAs and associated ceRNA networks in tomatoes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, M.; Lu, M.; Guo, Y.; Qin, F.; Jiang, C. The classical SOS pathway confers natural variation of salt tolerance in maize. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Xin, L.; Mounkaila Hamani, A.K.; Sun, W.; Wang, H.; Amin, A.S.; Wang, X.; Qin, A.; Gao, Y. Foliar application of melatonin positively affects the physio-biochemical characteristics of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) under the combined effects of low temperature and salinity stress. Plants 2023, 12, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.T.; Majeed, S.; Rana, I.A.; Ali, Z.; Jia, Y.; Du, X.; Hinze, L.; Azhar, M.T. Impact of salinity stress on cotton and opportunities for improvement through conventional and biotechnological approaches. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, D.M.; Shu, S.; Howson, R.; Neupane, R.; Hayes, R.D.; Fazo, J.; Mitros, T.; Dirks, W.; Hellsten, U.; Putnam, N.; et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1178–D1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamesch, P.; Berardini, T.Z.; Li, D.; Swarbreck, D.; Wilks, C.; Sasidharan, R.; Muller, R.; Dreher, K.; Alexander, D.L.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): Improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1202–D1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Zheng, C.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Lanczycki, C.J.; et al. CDD: Conserved domains and protein three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D348–D352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Birney, E.; Durbin, R.; Eddy, S.R.; Howe, K.L.; Sonnhammer, E.L. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Copley, R.R.; Doerks, T.; Ponting, C.P.; Bork, P. SMART: A web-based tool for the study of genetically mobile domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artimo, P.; Jonnalagedda, M.; Arnold, K.; Baratin, D.; Csardi, G.; de Castro, E.; Duvaud, S.; Flegel, V.; Fortier, A.; Gasteiger, E.; et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W597–W603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, H.R.; Islam, S.A.; David, A.; Sternberg, M.J. Phyre2.2: A community resource for template-based protein structure prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 168960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L. DALI and the persistence of protein shape. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, A.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Dong, Z.; Yao, L.; Han, X.; Wei, F. Characterization and gene expression analysis reveal universal stress proteins respond to abiotic stress in Gossypium hirsutum. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lu, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Yin, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ye, W. Temporal salt stress-induced transcriptome alterations and regulatory mechanisms revealed by PacBio long-reads RNA sequencing in Gossypium hirsutum. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Cui, R.; Wang, D.; Huang, H.; Rui, C.; Malik, W.A.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, N.; Liu, X.; et al. Combined transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses elucidate key salt-responsive biomarkers to regulate salt tolerance in cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rio, D.C.; Ares, M., Jr.; Hannon, G.J.; Nilsen, T.W. Purification of RNA Using TRIzol (TRI Reagent). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, 2010, pdb-prot5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, C.; Chen, Q.; Xie, Q.; Gao, Y.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, Y. Architecture and autoinhibitory mechanism of the plasma membrane Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter SOS1 in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.L.; Wendel, J.F. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005, 8, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.-H. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Li, Q.; Yin, H.; Qi, K.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Paterson, A.H. Gene duplication and evolution in recurring polyploidization–diploidization cycles in plants. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J. Evolutionary analysis of fiber-related gene families in diploid and polyploid cotton. Cotton Genom. Genet. 2025, 16, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.-Q.; Hua, Y.-P.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Yue, C.-P. Global landscapes of the Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter (NHX) family members uncover their potential roles in regulating rapeseed resistance to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, H.; Wang, Z.; Hussain, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Wang, X. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of the SOS1 gene family in the medicinal plant Paeonia ostii under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1614011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Sihui, L.; Li, C.; Hussain, Q.; Chen, P.; Hussain, M.A.; Nkoh Nkoh, J. SOS1 gene family in mangrove (Kandelia obovata): Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analyses under salt and copper stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Li, Z.; Sun, C.; Yin, S.; Wang, B.; Duan, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Pu, G. Genome-wide identification, molecular characterization, and gene expression analyses of honeysuckle NHX antiporters suggest their involvement in salt stress adaptation. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, U.; Song, Y.; Liang, C.; Abid, M.A.; Askari, M.; Myat, A.A.; Abbas, M.; Malik, W.; Ali, Z.; Guo, S.; et al. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of NHX gene family under salinity stress in Gossypium barbadense and its comparison with Gossypium hirsutum. Genes 2020, 11, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Guo, L.; Zhai, Y.; Hou, Z.; Wu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.; Gao, G.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of SOS1 gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum) and expression analyses under salt and hormone stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1201730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Petrov, V.; Yun, D.-J.; Gechev, T. Revisiting plant salt tolerance: Novel components of the SOS pathway. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, S.B.; Mitra, A.; Baumgarten, A.; Young, N.D.; May, G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2004, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Pei, W.; Wan, K.; Pan, R.; Zhang, W. LncRNA cis- and trans-regulation provides new insight into drought stress responses in wild barley. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, G. Structural and functional insight into the regulation of SOS1 activity. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1791–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katiyar-Agarwal, S.; Zhu, J.; Kim, K.; Agarwal, M.; Fu, X.; Huang, A.; Zhu, J.-K. The plasma membrane Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter SOS1 interacts with RCD1 and functions in oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18816–18821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Liu, H. Forkhead box protein O1: Functional diversity and post-translational modification, a new therapeutic target? Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mahi, H.; Pérez-Hormaeche, J.; De Luca, A.; Villalta, I.; Espartero, J.; Gámez-Arjona, F.; Fernández, J.L.; Bundó, M.; Mendoza, I.; Mieulet, D.; et al. A critical role of sodium flux via the plasma membrane Na⁺/H⁺ exchanger SOS1 in the salt tolerance of rice. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1046–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Tang, L.-H.; Nie, J.-W.; Zhang, C.-R.; Han, X.; Li, Q.-Y.; Qin, L.; Wang, M.-H.; Huang, X.; Yu, F.; et al. Structure and activation mechanism of the rice Salt Overly Sensitive 1 (SOS1) Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1924–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, B.; Shabala, L.; Zhou, M.; Venkataraman, G.; Solis, C.A.; Page, D.; Chen, Z.-H.; Shabala, S. Comparing essentiality of SOS1-mediated Na⁺ exclusion in salinity tolerance between cultivated and wild rice species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Ishitani, M.; Kim, C.; Zhu, J.-K. The Arabidopsis thaliana salt tolerance gene SOS1 encodes a putative Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6896–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhou, M.; Shabala, L.; Shabala, S. Physiological and molecular mechanisms mediating xylem Na⁺ loading in barley in the context of salinity stress tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, F.J.; Martinez-Atienza, J.; Villalta, I.; Jiang, X.; Kim, W.-Y.; Ali, Z.; Fujii, H.; Mendoza, I.; Yun, D.-J.; Zhu, J.-K.; et al. Activation of the plasma membrane Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter Salt-Overly-Sensitive 1 (SOS1) by phosphorylation of an auto-inhibitory C-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2611–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiguzov, A.; Vainonen, J.P.; Hunter, K.; Tossavainen, H.; Tiwari, A.; Järvi, S.; Hellman, M.; Aarabi, F.; Alseekh, S.; Wybouw, B.; et al. Arabidopsis RCD1 coordinates chloroplast and mitochondrial functions through interaction with ANAC transcription factors. eLife 2019, 8, e43284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Transcript ID | Gene Name | Start | End | Chr | Strand | CDS (bp) | Protein Length (Residues) | MW (kDa) | pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gohir.A01G036500.1.p | GhSOS1-1 | 2,907,644 | 2,914,117 | A01 | +ve | 1455 | 525 | 57,682.83 | 5.83 |

| Gohir.A01G085600.1.p | GhSOS1-2 | 12,718,712 | 12,722,123 | A01 | −ve | 1563 | 520 | 58,385.64 | 7.65 |

| Gohir.A06G181100.1.p | GhSOS1-3 | 123,551,254 | 123,560,921 | A06 | +ve | 1572 | 523 | 57,725.56 | 5.35 |

| Gohir.A07G039800.1.p | GhSOS1-4 | 5,201,392 | 5,208,768 | A07 | −ve | 1728 | 575 | 62,278.06 | 5.91 |

| Gohir.A02G103100.1.p | GhSOS1-5 | 47,530,475 | 47,534,471 | A02 | +ve | 2403 | 557 | 86,844.88 | 8.63 |

| Gohir.A02G103200.1.p | GhSOS1-6 | 47,628,984 | 47,631,749 | A02 | +ve | 774 | 493 | 86,783.59 | 8.70 |

| Gohir.A02G107001.1.p | GhSOS1-7 | 53,796,550 | 53,799,059 | A02 | −ve | 2115 | 543 | 76,359.76 | 8.99 |

| Gohir.A13G193600.1.p | GhSOS1-8 | 106,866,865 | 106,874,598 | A13 | +ve | 1800 | 515 | 64,659.58 | 6.03 |

| Gohir.D01G023800.1.p | GhSOS1-9 | 2,596,207 | 2,602,613 | D01 | +ve | 1344 | 508 | 56,877.92 | 5.51 |

| Gohir.D01G209600.1.p | GhSOS1-10 | 64,539,990 | 64,545,894 | D01 | −ve | 2484 | 535 | 90,258.69 | 8.17 |

| Gohir.D06G166000.1.p | GhSOS1-11 | 58,829,180 | 58,832,616 | D06 | +ve | 2472 | 523 | 90,511.16 | 8.49 |

| Gohir.D08G235650.1.p | GhSOS1-12 | 66,082,200 | 66,087,538 | D08 | +ve | 1722 | 567 | 63,860.61 | 8.09 |

| Gohir.D11G077600.1.p | GhSOS1-13 | 6,530,454 | 6,533,042 | D11 | +ve | 2361 | 534 | 87,643.38 | 6.43 |

| Gohir.D11G248200.2.p | GhSOS1-14 | 54,223,810 | 54,227,732 | D11 | −ve | 1605 | 542 | 59,734.17 | 8.64 |

| Gohir.D11G272700.1.p | GhSOS1-15 | 61,187,575 | 61,191,154 | D11 | −ve | 1629 | 515 | 59,787.77 | 6.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqra, L.; Shahid, M.N.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Genome-Wide Identification and Abiotic Stress-Responsive Expression Analysis of the SOS1 Gene Family in Gossypium hirsutum L. Life 2025, 15, 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121843

Iqra L, Shahid MN, Caetano-Anollés G. Genome-Wide Identification and Abiotic Stress-Responsive Expression Analysis of the SOS1 Gene Family in Gossypium hirsutum L. Life. 2025; 15(12):1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121843

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqra, Laraib, Muhammad Naveed Shahid, and Gustavo Caetano-Anollés. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification and Abiotic Stress-Responsive Expression Analysis of the SOS1 Gene Family in Gossypium hirsutum L." Life 15, no. 12: 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121843

APA StyleIqra, L., Shahid, M. N., & Caetano-Anollés, G. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification and Abiotic Stress-Responsive Expression Analysis of the SOS1 Gene Family in Gossypium hirsutum L. Life, 15(12), 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121843