Dynamic Gene Network Alterations and Identification of Key Genes in the Spleen During African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Original Experimental Design

2.2. RNA-Seq Data Processing

2.3. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Construction in Spleen Tissue During ASFV Infection Time

2.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Gene Co-Expression Modules

2.5. Pathway and Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing Quality and Read Statistics

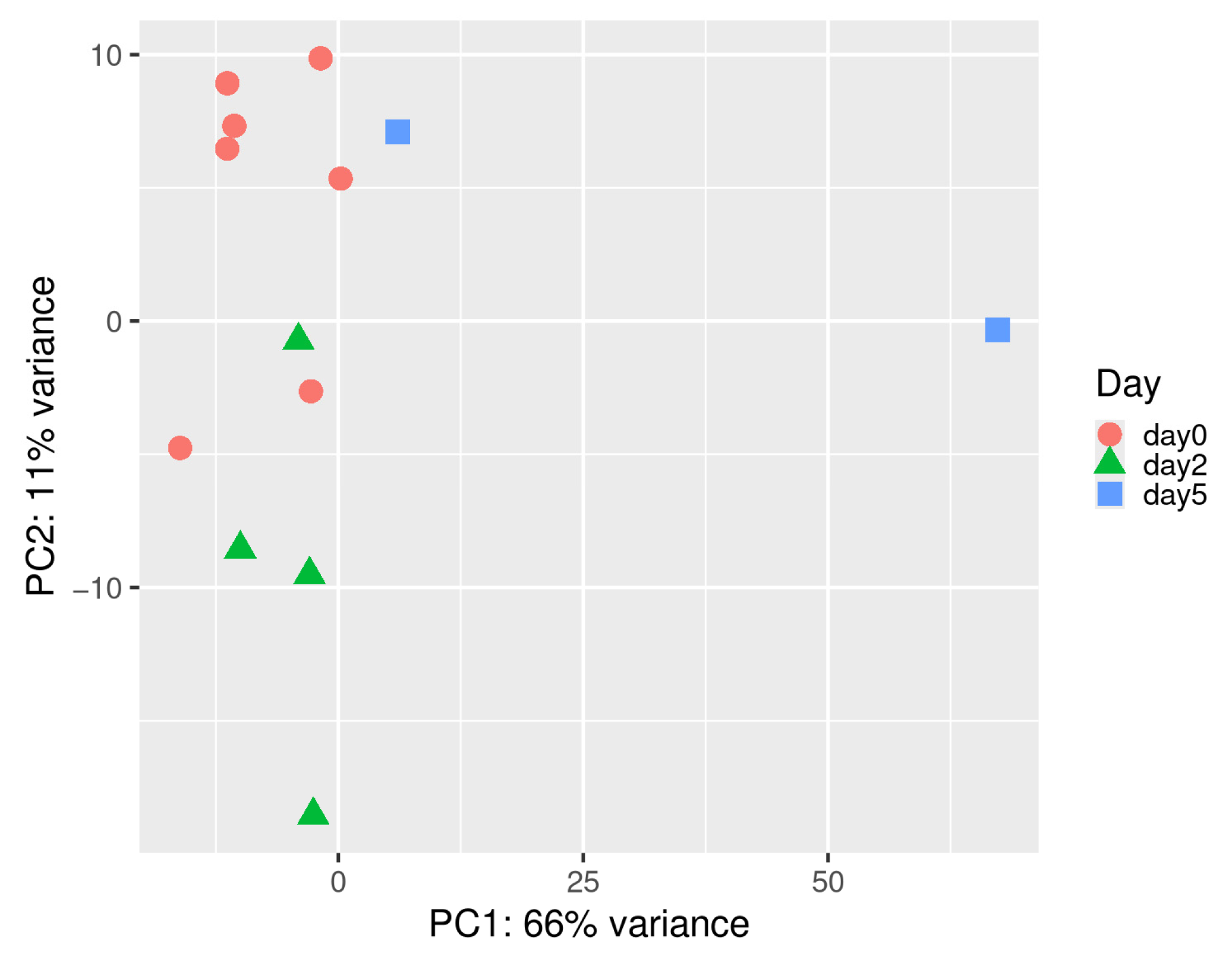

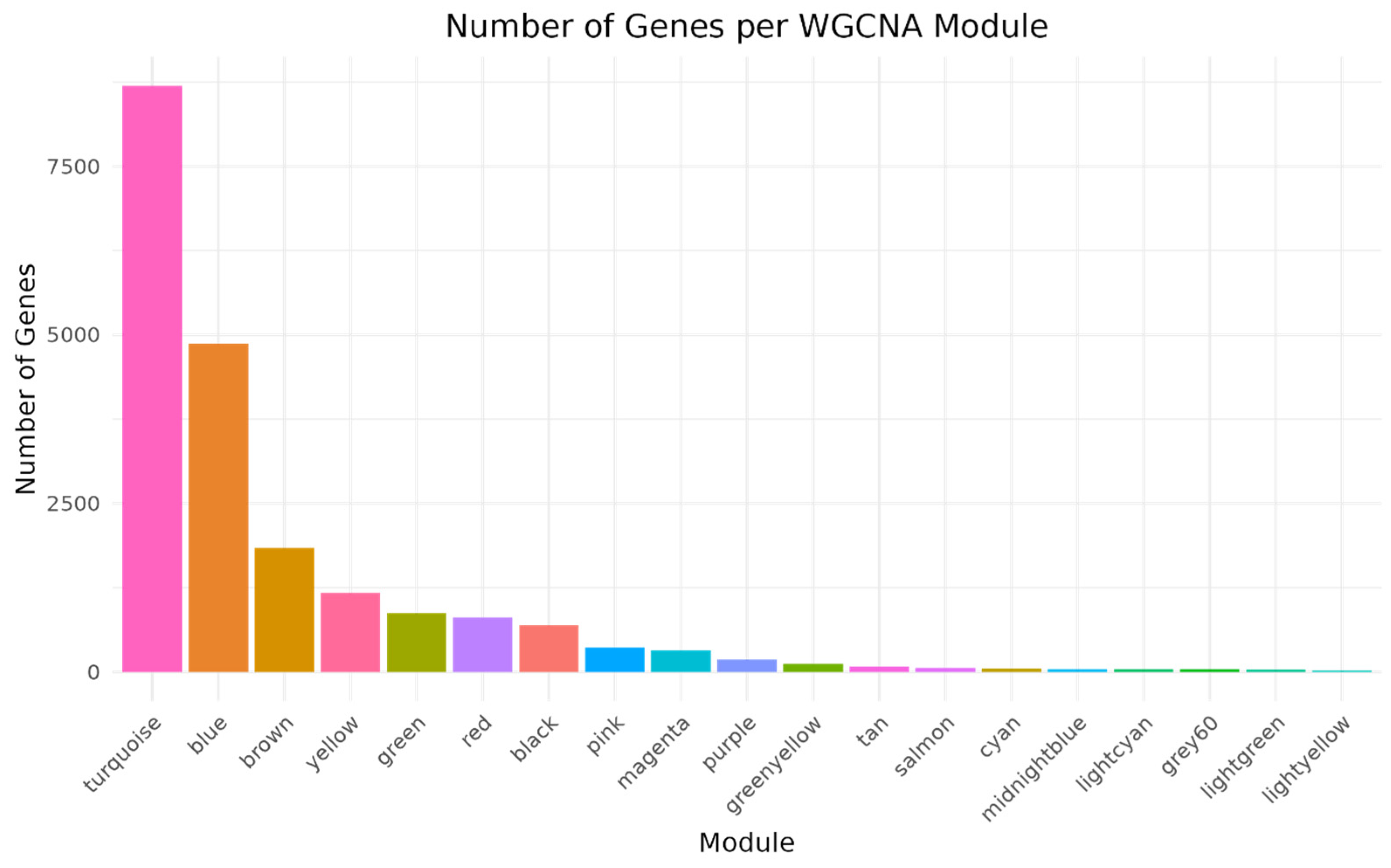

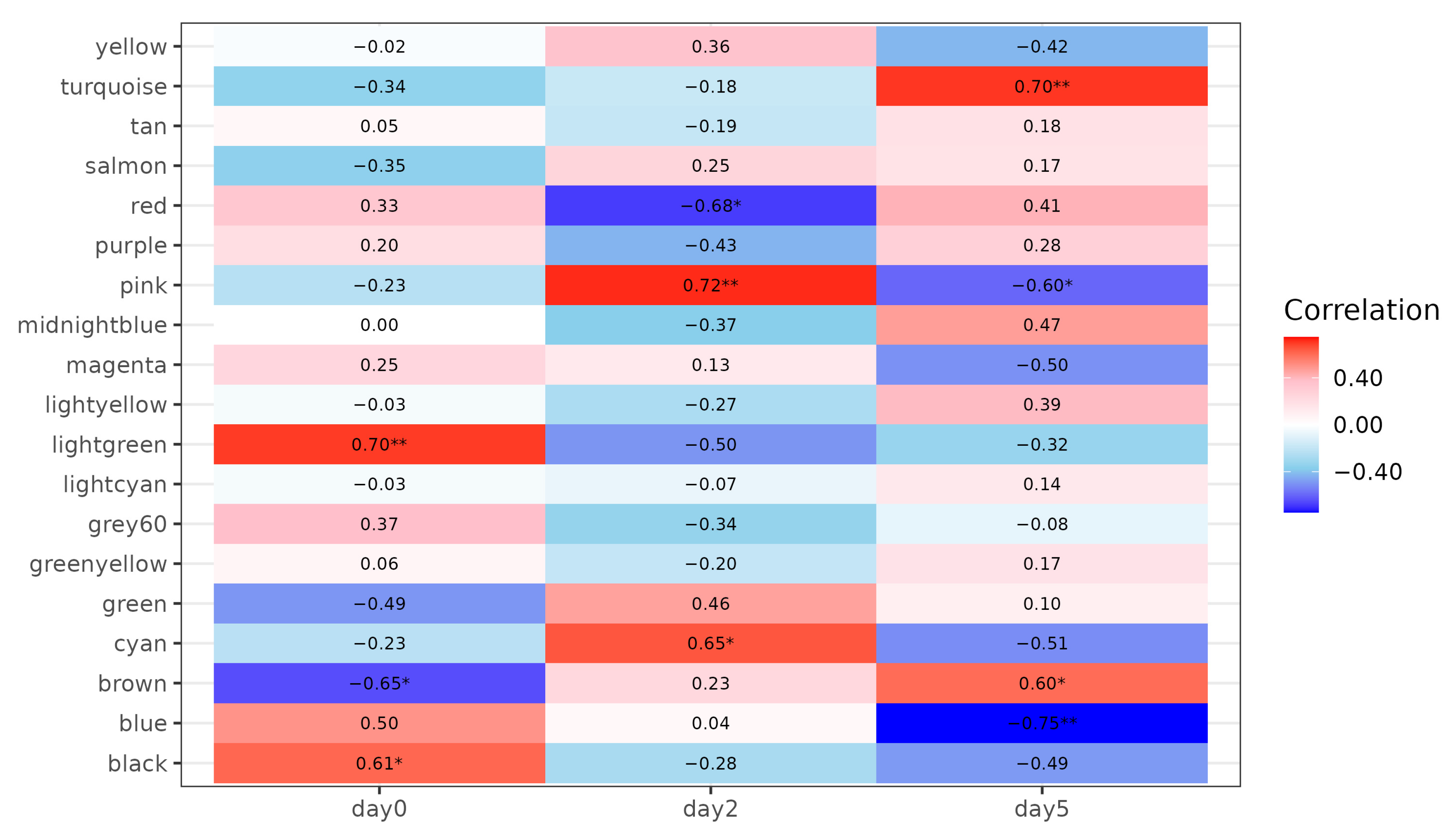

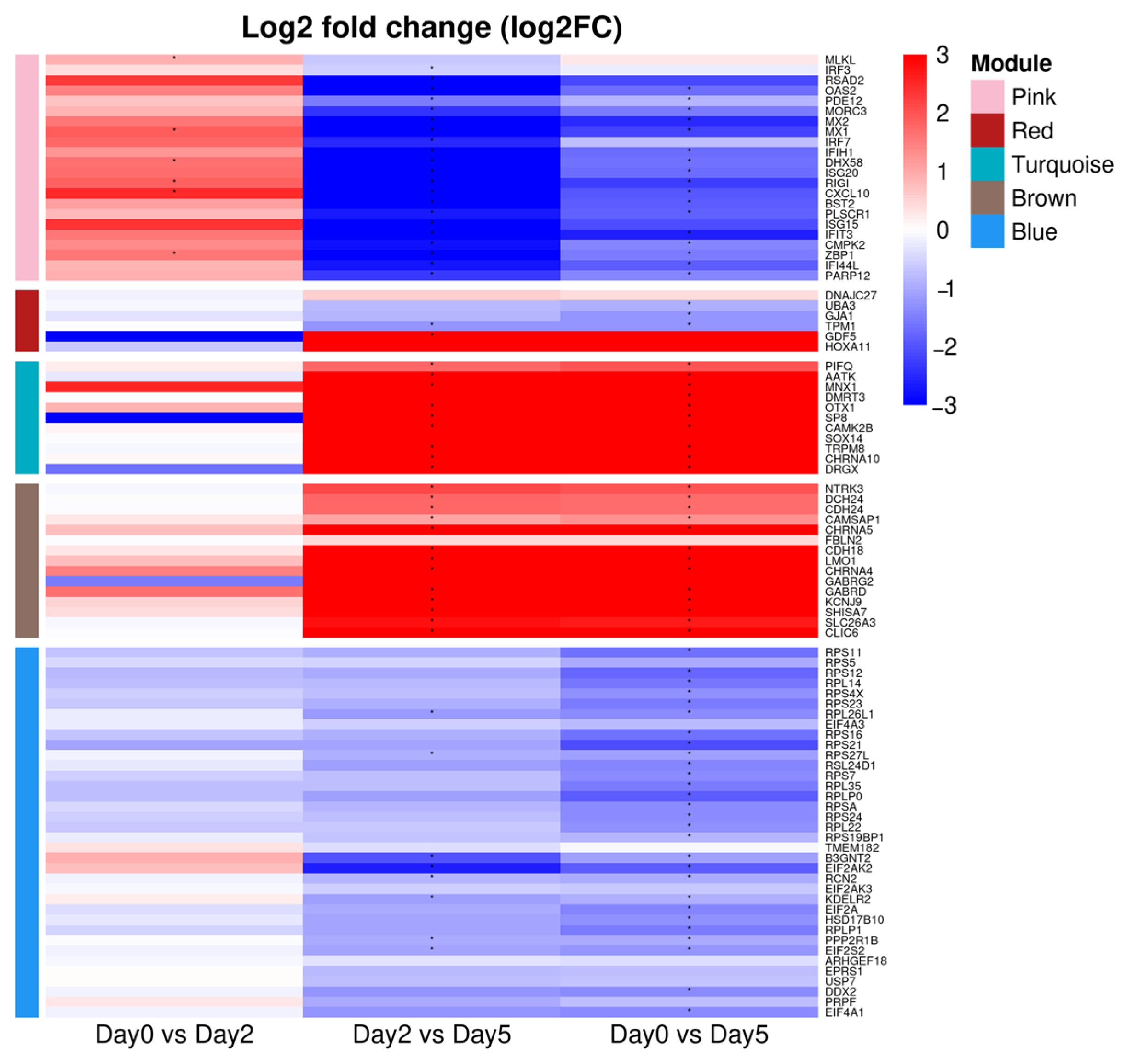

3.2. Construction of Co-Expression Network in Spleen Tissue and Correlation Analysis with Infection Time Points

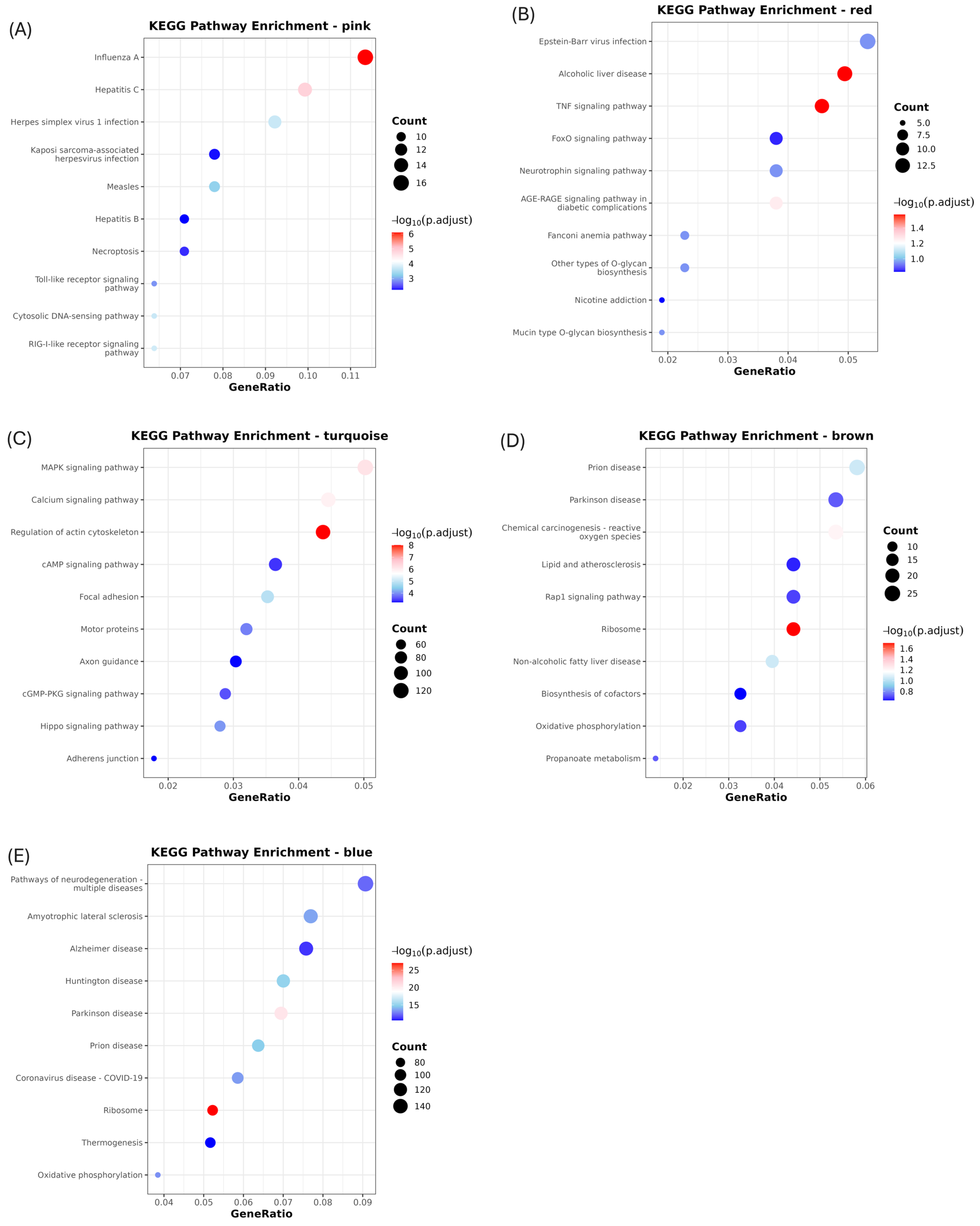

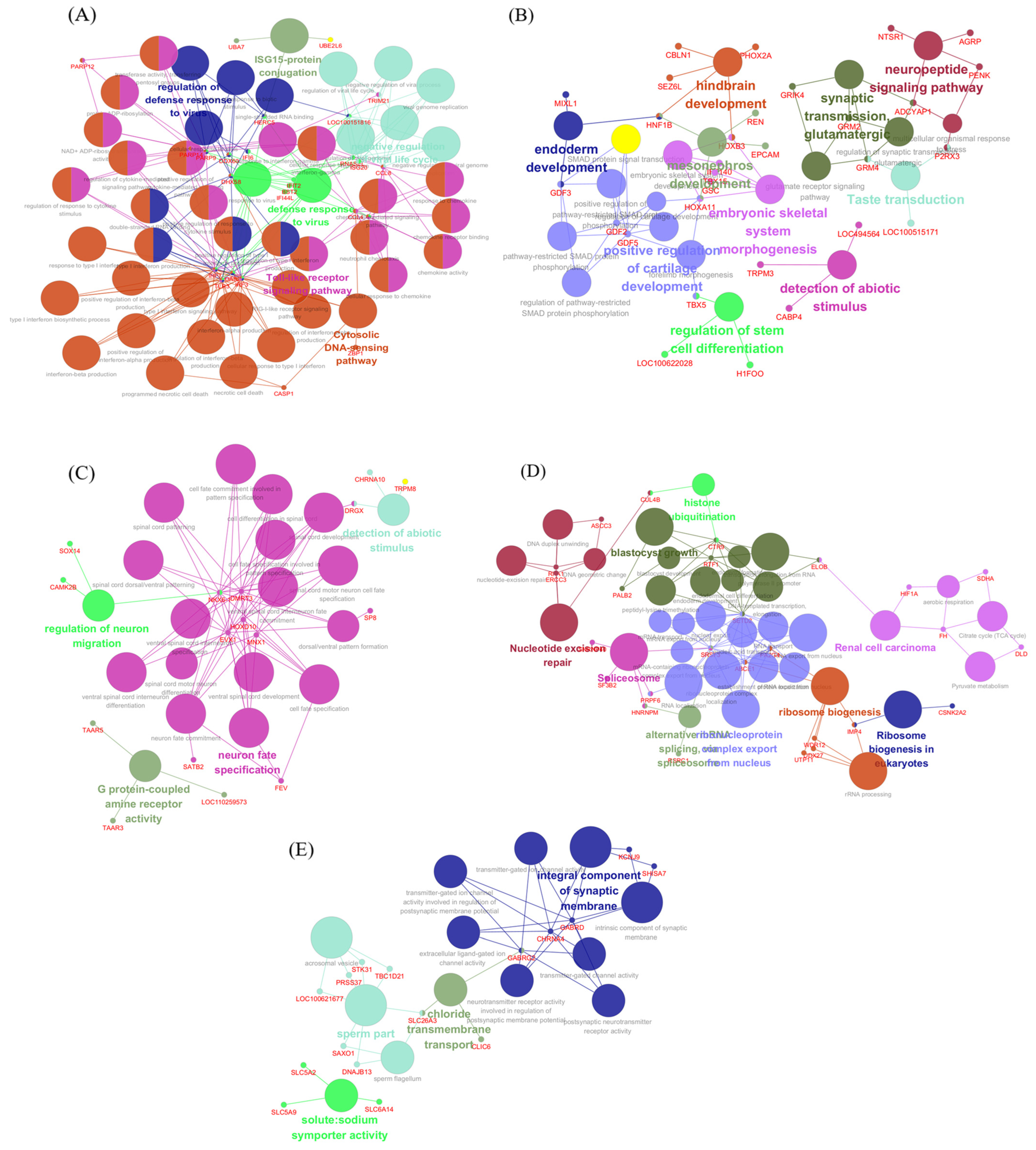

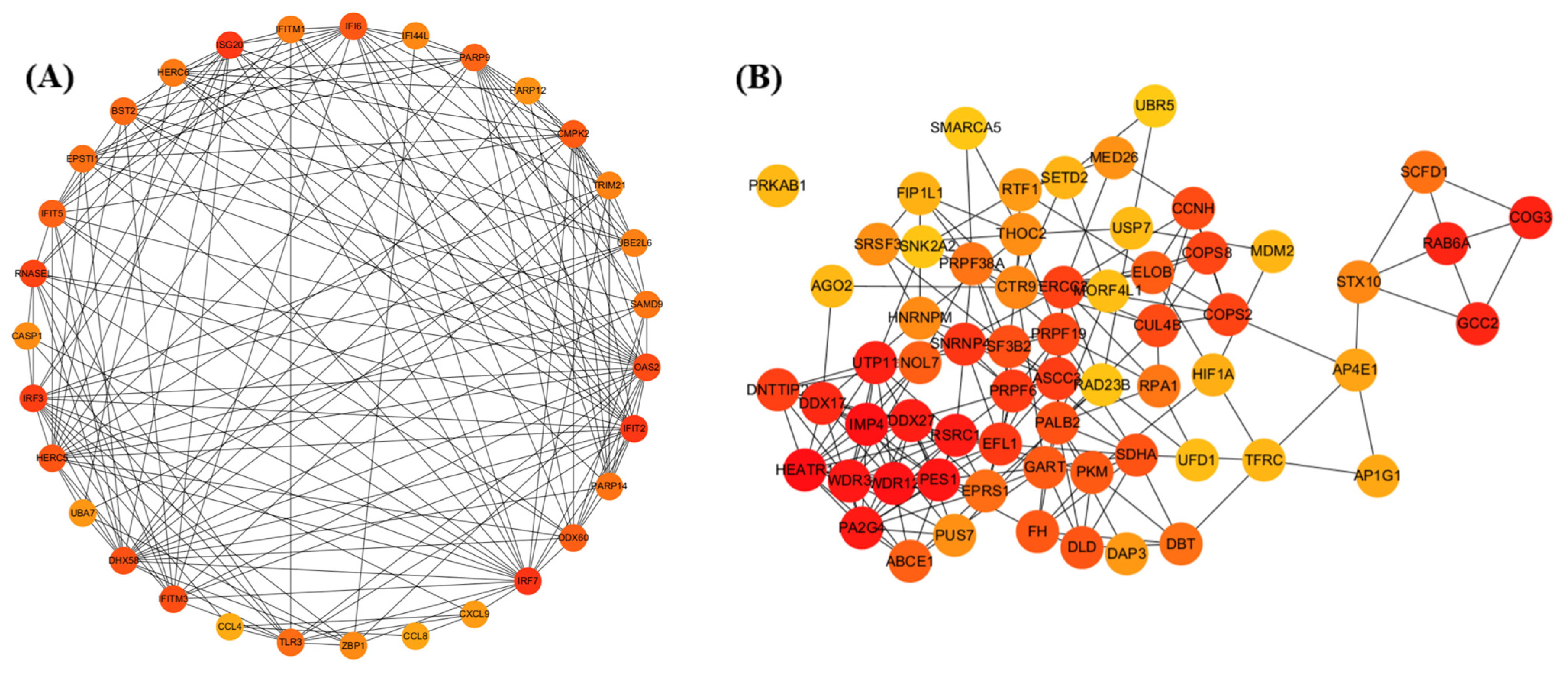

3.3. Activation of Innate Antiviral Response–Associated Co-Expression Modules at 2 dpi

3.4. Downregulation of Gene Co-Expression Modules at 2 dpi

3.5. Modules Activated During Later Infection

3.6. Modules Showing Decreased or Changing Expression During Infection

4. Discussion

4.1. Early Macrophage-Driven Antiviral and Inflammatory Activation at 2 dpi

4.2. Modulation of TNF/TGF-β-Associated Gene Expression at 2 dpi

4.3. Upregulation of Signaling and Translation-Associated Modules at 5 dpi and Their Pathological Implications

4.4. Suppression of Antiviral and Metabolic Modules at 5 dpi

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallardo, M.C.; Reoyo, A.T.; Fernandez-Pinero, J.; Iglesias, I.; Munoz, M.J.; Arias, M.L. African swine fever: A global view of the current challenge. Porc. Health Manag. 2015, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.; Borca, M.; Dixon, L.; Revilla, Y.; Rodriguez, F.; Escribano, J.M.; ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Asfarviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 613–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.K.; Chapman, D.A.; Netherton, C.L.; Upton, C. African swine fever virus replication and genomics. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmink, J.D.; Abkallo, H.M.; Henson, S.P.; Khazalwa, E.M.; Oduor, B.; Lacasta, A.; Okoth, E.; Riitho, V.; Fuchs, W.; Bishop, R.P.; et al. The African Swine Fever Isolate ASFV-Kenya-IX-1033 Is Highly Virulent and Stable after Propagation in the Wild Boar Cell Line WSL. Viruses 2022, 14, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter-Louis, C.; Conraths, F.J.; Probst, C.; Blohm, U.; Schulz, K.; Sehl, J.; Fischer, M.; Forth, J.H.; Zani, L.; Depner, K.; et al. African Swine Fever in Wild Boar in Europe-A Review. Viruses 2021, 13, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Shan, B.; Wei, S.; An, T.; Shen, G.; Chen, Z. Prevalence of African Swine Fever in China, 2018–2019. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Hong, S.K.; Lee, I.; Yoo, D.S.; Jung, C.S.; Lee, E.; Wee, S.H. Clinical symptoms of African swine fever in domestic pig farms in the Republic of Korea, 2019. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2245–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, D.S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, E.S.; Lim, J.S.; Hong, S.K.; Lee, I.S.; Jung, C.S.; Yoon, H.C.; Wee, S.H.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; et al. Transmission Dynamics of African Swine Fever Virus, South Korea, 2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.S.; Andraud, M.; Kim, E.; Vergne, T. Three Years of African Swine Fever in South Korea (2019–2021): A Scoping Review of Epidemiological Understanding. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2023, 2023, 4686980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Le, P.N.; Mai, N.T.A.; Dong, V.H.; Bui, T.A.D.; Nguyen, T.L.; Ambagala, A.; Le, V.P. Pathological Characteristics of Domestic Pigs Orally Infected with the Virus Strain Causing the First Reported African Swine Fever Outbreaks in Vietnam. Pathogens 2023, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, J.M.; Galindo, I.; Alonso, C. Antibody-mediated neutralization of African swine fever virus: Myths and facts. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, S.; Williamson, A.L.; Heath, L.; Carulei, O. Genome Sequences of Three African Swine Fever Viruses of Genotypes IV and XX from Zaire and South Africa, Isolated from a Domestic Pig (Sus scrofa domesticus), a Warthog (Phacochoerus africanus), and a European Wild Boar (Sus scrofa). Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9, e00341-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, D.; Prakash, A.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Salman, M.; Suntisukwattana, R.; Atthaapa, W.; Tantituvanont, A.; Lin, H.; Songkasupa, T.; Nilubol, D. Comprehensive Characterization of the Genetic Landscape of African Swine Fever Virus: Insights into Infection Dynamics, Immunomodulation, Virulence and Genes with Unknown Function. Animals 2024, 14, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Li, F.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zou, X. African Swine Fever Virus Immunosuppression and Virulence-Related Gene. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 8268–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Ren, J.; Li, D.; Ru, Y.; Qin, X.; Feng, T.; Tian, H.; Lu, B.; Shi, D.; Shi, Z.; et al. Combinational Deletions of MGF110-9L and MGF505-7R Genes from the African Swine Fever Virus Inhibit TBK1 Degradation by an Autophagy Activator PIK3C2B To Promote Type I Interferon Production. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0022823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droesbeke, B.; Balmelle, N.; Cay, A.B.; Han, S.J.; Oh, D.; Nauwynck, H.J.; Tignon, M. Replication Kinetics and Infectivity of African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) Variants with Different Genotypes or Levels of Virulence in Cell Culture Models of Primary Porcine Macrophages. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1690–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, G.; Graham, S.P.; Giudici, S.D.; Bonelli, P.; Pilo, G.; Anfossi, A.G.; Pittau, M.; Nicolussi, P.S.; Laddomada, A.; Oggiano, A. Characterization of the interaction of African swine fever virus with monocytes and derived macrophage subsets. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 198, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, E.G.; Riera, E.; Nogal, M.; Gallardo, C.; Fernandez, P.; Bello-Morales, R.; Lopez-Guerrero, J.A.; Chitko-McKown, C.G.; Richt, J.A.; Revilla, Y. Phenotyping and susceptibility of established porcine cells lines to African Swine Fever Virus infection and viral production. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, N.; Ou, Y.; Pejsak, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Roles of African Swine Fever Virus Structural Proteins in Viral Infection. J. Vet. Res. 2017, 61, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Xia, N.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Q.; Jiang, S.; Luo, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, N.; Zhang, Q.; Meurens, F.; et al. African Swine Fever Virus Structural Protein p17 Inhibits cGAS-STING Signaling Pathway Through Interacting with STING. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 941579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, A.; Matamoros, T.; Guerra, M.; Andres, G. A Proteomic Atlas of the African Swine Fever Virus Particle. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01293-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zhang, T.; Jia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ahsan, A.; Zhao, X.; Chen, T.; Shen, Z.; Shen, N. Temporally integrated transcriptome analysis reveals ASFV pathology and host response dynamics. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 995998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Cao, Y.; Jiao, P.; Yu, P.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Zhou, X.; Qi, Y.; Sun, L.; Liu, D.; et al. Synergistic effect of the responses of different tissues against African swine fever virus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e204–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Mao, R.; Liu, B.; Liu, H.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Single-cell profiling of African swine fever virus disease in the pig spleen reveals viral and host dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2312150121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machuka, E.M.; Juma, J.; Muigai, A.W.T.; Amimo, J.O.; Pelle, R.; Abworo, E.O. Transcriptome profile of spleen tissues from locally-adapted Kenyan pigs (Sus scrofa) experimentally infected with three varying doses of a highly virulent African swine fever virus genotype IX isolate: Ken12/busia.1 (ken-1033). BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Jaiswal, V.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, A.; Afroz, A.; Kumar, A. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of African swine fever virus from a pig farm in India. Vet. Res. Forum 2024, 15, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.I.; Sheet, S.; Bui, V.N.; Dao, D.T.; Bui, N.A.; Kim, T.H.; Cha, J.; Park, M.R.; Hur, T.Y.; Jung, Y.H.; et al. Transcriptome profiles of organ tissues from pigs experimentally infected with African swine fever virus in early phase of infection. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2366406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Xiang, G.; Zhao, X.; Nan, Y.; Zhao, D.; Ding, Q. Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of highly virulent African swine fever virus infection reveals complex and unique virus host interaction. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 261, 109211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Zhou, L.; Du, H.; Okoth, E.; Mrode, R.; Jin, W.; Hu, Z.; Liu, J.F. Transcriptome analysis reveals gene expression changes of pigs infected with non-lethal African swine fever virus. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2023, 46, e20230037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaing, C.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Allen, J.E.; Certoma, A.; Thissen, J.B.; Bingham, J.; Rowe, B.; White, J.R.; Wynne, J.W.; Johnson, D.; et al. Gene expression analysis of whole blood RNA from pigs infected with low and high pathogenic African swine fever viruses. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinat, C.; Reis, A.L.; Netherton, C.L.; Goatley, L.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Dixon, L. Dynamics of African swine fever virus shedding and excretion in domestic pigs infected by intramuscular inoculation and contact transmission. Vet. Res. 2014, 45, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marku, M.; Pancaldi, V. From time-series transcriptomics to gene regulatory networks: A review on inference methods. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Lei, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Xu, W.; Xie, T.; Wang, D.; Peng, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Interactome between ASFV and host immune pathway proteins. mSystems 2023, 8, e0047123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, F.J. Comparative Pathology and Pathogenesis of African Swine Fever Infection in Swine. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, C.H.; Chen, S.H.; Wu, H.H.; Ho, C.W.; Ko, M.T.; Lin, C.Y. cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8 (Suppl. S4), S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustamante-Barrientos, F.A.; Luque-Campos, N.; Araya, M.J.; Lara-Barba, E.; de Solminihac, J.; Pradenas, C.; Molina, L.; Herrera-Luna, Y.; Utreras-Mendoza, Y.; Elizondo-Vega, R.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders: Potential therapeutic application of mitochondrial transfer to central nervous system-residing cells. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Gu, T.; Gao, X.; Song, Z.; Liu, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Y. African swine fever virus enhances viral replication by increasing intracellular reduced glutathione levels, which suppresses stress granule formation. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.H.; Wu, D.W.; Wu, C.H.; Hung, L.F.; Huang, C.Y.; Ka, S.M.; Chen, A.; Chang, Z.F.; Ho, L.J. Mitochondrial CMPK2 mediates immunomodulatory and antiviral activities through IFN-dependent and IFN-independent pathways. iScience 2021, 24, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, M.E. ADP-Ribosylation During Coronavirus Infection: Connections to Viral Protein Modification, Innate Immunity, and the Toxin Response. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maelfait, J.; Rehwinkel, J. The Z-nucleic acid sensor ZBP1 in health and disease. J. Exp. Med. 2023, 220, e20221156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, L.; Wachsmuth, L.; Kumari, S.; Schwarzer, R.; Wagner, T.; Jiao, H.; Pasparakis, M. ZBP1 causes inflammation by inducing RIPK3-mediated necroptosis and RIPK1 kinase activity-independent apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2024, 31, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, D.C.; Habgood-Coote, D.; Clare, S.; Brandt, C.; Bassano, I.; Kaforou, M.; Herberg, J.; Levin, M.; Eleouet, J.F.; Kellam, P.; et al. Interferon-Induced Protein 44 and Interferon-Induced Protein 44-Like Restrict Replication of Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00297-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Liang, S.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; He, F.; Shalapour, S.; Lin, X.J.; Wong, J.; Ding, S.; Seki, E.; Schnabl, B.; et al. New mitochondrial DNA synthesis enables NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2018, 560, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, J.B.; Hsu, J.C.; Xia, H.; Han, P.; Suh, H.W.; Grove, T.L.; Morrison, J.; Shi, P.Y.; Cresswell, P.; Laurent-Rolle, M. CMPK2 restricts Zika virus replication by inhibiting viral translation. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Lv, J.; Wang, W.; Guo, R.; Zhong, C.; Antia, A.; Zeng, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, J.; et al. CMPK2 is a host restriction factor that inhibits infection of multiple coronaviruses in a cell-intrinsic manner. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Cao, H.; Li, W.; Hu, Z.; Rong, Z.; Yin, M.; Tian, L.; Hu, D.; Li, X.; Qian, P. African swine fever virus MGF505-6R attenuates type I interferon production by targeting STING for degradation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1380220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Weng, W.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Jiang, F.; Qu, Y.; Li, Q.; Gao, P.; Zhou, L.; et al. The African swine fever virus MGF360-16R protein functions as a mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis inducer by competing with BAX to bind to the HSP60 protein. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e01401-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAntoneo, C.; Herbert, A.; Balachandran, S. Z-form nucleic acid-binding protein 1 (ZBP1) as a sensor of viral and cellular Z-RNAs: Walking the razor’s edge. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2023, 83, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hao, Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, X.; Zhao, D.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, H. ASFV infection induces macrophage necroptosis and releases proinflammatory cytokine by ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL necrosome activation. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1419615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Wu, P.; Zhang, B.X.; Yang, C.R.; Huang, J.; Wu, L.; Guo, S.H.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, Y.; Yin, Y.; et al. ZBP1 senses splicing aberration through Z-RNA to promote cell death. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 1775–1789.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Yang, J.; Zou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Sun, X.; Lin, X.; Jin, M. African swine fever virus infection activates inflammatory responses through downregulation of the anti-inflammatory molecule C1QTNF3. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1002616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.H.; Hong, S.K.; Kim, D.Y.; Jang, M.K.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, E.M.; Park, J.H.; Suh, T.Y.; Choi, J.G.; et al. Pathogenicity and Pathological Characteristics of African Swine Fever Virus Strains from Pig Farms in South Korea from 2022 to January 2023. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solikhah, T.I.; Rostiani, F.; Nanra, A.F.P.; Dewi, A.; Nurbadri, P.H.; Agustin, Q.A.D.; Solikhah, G.P. African swine fever virus: Virology, pathogenesis, clinical impact, and global control strategies. Vet. World 2025, 18, 1599–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaryan, H.; Karalova, E.; Voskanyan, H.; Ter-Pogossyan, Z.; Nersisyan, N.; Hakobyan, A.; Saroyan, D.; Karalyan, Z. Evaluation of hemostaseological status of pigs experimentally infected with African swine fever virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 174, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Gong, T.; Kuang, Q.; Xiang, Q.; Gong, L.; Zhang, G. Deoxycholic acid inhibits ASFV replication by inhibiting MAPK signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 130939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raker, V.K.; Becker, C.; Steinbrink, K. The cAMP Pathway as Therapeutic Target in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serezani, C.H.; Ballinger, M.N.; Aronoff, D.M.; Peters-Golden, M. Cyclic AMP: Master regulator of innate immune cell function. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 39, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, A.; Quintas, A.; Sanchez, E.G.; Sabina, P.; Nogal, M.; Carrasco, L.; Revilla, Y. Regulation of host translational machinery by African swine fever virus. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, F.; Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Xue, Z.; Cao, W.; Liu, X.; Zheng, H. African Swine Fever Virus Regulates Host Energy and Amino Acid Metabolism To Promote Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0191921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta-Geijo, M.; Chiappi, M.; Galindo, I.; Barrado-Gil, L.; Muñoz-Moreno, R.; Carrascosa, J.L.; Alonso, C. Cholesterol Flux Is Required for Endosomal Progression of African Swine Fever Virions during the Initial Establishment of Infection. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 1534–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Moon, A.; Childs, K.; Goodbourn, S.; Dixon, L.K. The African swine fever virus DP71L protein recruits the protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit to dephosphorylate eIF2alpha and inhibits CHOP induction but is dispensable for these activities during virus infection. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 10681–10689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrado-Gil, L.; Del Puerto, A.; Munoz-Moreno, R.; Galindo, I.; Cuesta-Geijo, M.A.; Urquiza, J.; Nistal-Villan, E.; Maluquer de Motes, C.; Alonso, C. African Swine Fever Virus Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme Interacts with Host Translation Machinery to Regulate the Host Protein Synthesis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 622907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekakoro, J.E.; Nassali, A.; Hauser, C.; Ochoa, K.; Ndoboli, D.; Okwasiimire, R.; Kayaga, E.B.; Wampande, E.M.; Havas, K.A. A description of the clinical signs and lesions of African swine fever, and its differential diagnoses in pigs slaughtered at selected abattoirs in central Uganda. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1568095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoni, G.; Pedrera, M.; Sanchez-Cordon, P.J. African Swine Fever Virus Infection and Cytokine Response In Vivo: An Update. Viruses 2023, 15, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Huang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Gao, Q. IRF7: Role and regulation in immunity and autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1236923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeonwumelu, I.J.; Garcia-Vidal, E.; Ballana, E. JAK-STAT Pathway: A Novel Target to Tackle Viral Infections. Viruses 2021, 13, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutell, C.; Canning, M.; Orr, A.; Everett, R.D. Reciprocal activities between herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP0, a ubiquitin E3 ligase, and ubiquitin-specific protease USP7. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 12342–12354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holowaty, M.N.; Zeghouf, M.; Wu, H.; Tellam, J.; Athanasopoulos, V.; Greenblatt, J.; Frappier, L. Protein profiling with Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1 reveals an interaction with the herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease HAUSP/USP7. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 29987–29994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojagora, A.; Saridakis, V. USP7 manipulation by viral proteins. Virus Res. 2020, 286, 198076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riera, E.; García-Belmonte, R.; Madrid, R.; Pérez-Núñez, D.; Revilla, Y. African swine fever virus ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme pI215L inhibits IFN-I signaling pathway through STAT2 degradation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1081035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Peng, J.-L.; Xu, Z.-S.; Xiong, M.-G.; Wu, H.-N.; Wang, S.-Y.; Li, D.; Zhu, G.-Q.; Ran, Y.; Wang, Y.-Y. African Swine Fever Virus Cysteine Protease pS273R Inhibits Type I Interferon Signaling by Mediating STAT2 Degradation. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e01942-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, G.; Liu, C.; Bao, M.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Huang, L.; et al. African swine fever virus pS273R antagonizes stress granule formation by cleaving the nucleating protein G3BP1 to facilitate viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.; Yao, P.; Terenzi, F.; Jia, J.; Ray, P.S.; Fox, P.L. The GAIT translational control system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2018, 9, e1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Jia, J.; Arif, A.; Ray, P.S.; Fox, P.L. The GAIT system: A gatekeeper of inflammatory gene expression. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Qi, Y.; Han, X.; Zhou, X.; Miao, F.; Chen, T.; et al. Cytokine Storm in Domestic Pigs Induced by Infection of Virulent African Swine Fever Virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 601641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, P.; Chauhan, M.; Rajeev, T.; Chakraborty, R.; Bisht, K.; Madan, M.; Shankaran, D.; Ramalingam, S.; Gandotra, S.; Rao, V. The mitochondrial gene-CMPK2 functions as a rheostat for macrophage homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 935710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamunusinghe, D.D. African Swine Fever Virus EP152R Inhibits Type I Interferon Production by Negatively Regulating the cGAS-STING-Mediated Signaling Pathway. Master’s Thesis, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, M.; Tian, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. The African swine fever virus gene MGF_360-4L inhibits interferon signaling by recruiting mitochondrial selective autophagy receptor SQSTM1 degrading MDA5 antagonizing innate immune responses. mBio 2025, 16, e0267724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metric | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input Reads Pairs | 36,484,500 | 3,403,084 | 32,438,387 | 42,868,927 |

| Both Surviving | 35,227,179 | 3,469,893 | 31,174,125 | 41,644,734 |

| Forward Only Surviving | 1,089,212 | 266,983 | 517,700 | 1,719,073 |

| Reverse Only Surviving | 134,419 | 35,440 | 105,449 | 231,891 |

| Dropped | 33,691 | 9973 | 23,479 | 63,752 |

| Module | Enriched KEGG Pathway and Gene Ontology (Biological Process) Terms | Adjusted p-Value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pink | Influenza A Hepatitis C necroptosis RIG-I-like receptor signaling Toll-like receptor signaling cyt solic DNA sensing pathway defense response to virus (GO:0051607) innate immune response (GO:0045087) response to virus (GO:0009615) | 8.11 × 10−7 1.39 × 10−5 1.30 × 10−3 1.67 × 10−4 1.30 × 10−3 1.90 × 10−4 1.73 × 10−18 1.69 × 10−13 1.66 × 10−17 | MLKL, IRF3, RSAD2, OAS2, OASL, PDE12, MORC3, MX2, MX1, IRF7, IFIH1, TRIM65, DHX58, ISG20, RIGI (DDX58), CXCL10, BST2, PLSCR1, ISG15, IFIT3, ZBP1, IFI44L, PARP12, CMPK2 |

| Cyan | Huntington’s disease selenocompound metabolism amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | 0.05 0.05 0.05 | |

| Red | TNF signaling | 0.026 | DNAJC27, UBA3, GJA1, TPM1, GDF5, HOXA11 |

| Turquoise | Huntington’s disease selenocompound metabolism amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | 0.05 0.05 0.05 | MNX1, DMRT3, OTX1, SP8, CAMK2B, SOX14, TRPM8, CHRNA10, DRGX |

| Brown | ribosome | 1.99035 × 10−2 | NTRK3, DCH24, CDH24, CDH13, CAMSAP1, CHRNA5, FBLN2, CDH18, LMO1, CHRNA4, GABRG2, GABRD, KCNJ9, SHISA7, SLC26A3, CLIC6 |

| blue | oxidative phosphorylation ribosome function thermogenesis Alzheimer’s disease Parkinson’s disease Huntington’s disease protein translation (GO:0006412) ribosome biogenesis (GO:0042254) rRNA metabolic process (GO:0016072) ribonucleoprotein complex bi genesis (GO:0022613) | 5.9663 × 10−14 9.4239 × 10−28 2.4564 × 10−11 6.293 × 10−12 3.2788 × 10−21 8.0229 × 10−16 2.2162 × 10−11 7.7883 × 10−10 4.7359 × 10−8 2.2162 × 10−11 | RPS11, RPS5, RPS12, RPL14, RPS4X, RPS23, RPL26L1, EIF4A3, RPS16, RPS21, RPS27L, RSL24D1, RPS7, RPL35, RPLP0, RPSA, RPS24, RPL22, RPS19BP1, TMEM182, B3GNT2, EIF2AK2, RCN2, EIF2AK3, KDELR2, EIF2A, HSD17B10, RPLP1, PPP2R1B, EIF2S2, ARHGEF18, EPRS1, USP7, WDR12, HNRNPM, DDX2, PRPF, EIF4A1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Go, J.-B.; Bui, V.N.; Dao, D.T.; Bui, N.A.; Cha, J.; Lee, H.S.; Lim, D. Dynamic Gene Network Alterations and Identification of Key Genes in the Spleen During African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) Infection. Life 2025, 15, 1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121844

Go J-B, Bui VN, Dao DT, Bui NA, Cha J, Lee HS, Lim D. Dynamic Gene Network Alterations and Identification of Key Genes in the Spleen During African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) Infection. Life. 2025; 15(12):1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121844

Chicago/Turabian StyleGo, Jae-Beom, Vuong Nghia Bui, Duy Tung Dao, Ngoc Anh Bui, Jihye Cha, Hu Suk Lee, and Dajeong Lim. 2025. "Dynamic Gene Network Alterations and Identification of Key Genes in the Spleen During African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) Infection" Life 15, no. 12: 1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121844

APA StyleGo, J.-B., Bui, V. N., Dao, D. T., Bui, N. A., Cha, J., Lee, H. S., & Lim, D. (2025). Dynamic Gene Network Alterations and Identification of Key Genes in the Spleen During African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) Infection. Life, 15(12), 1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121844