Using Radiomics and Explainable Ensemble Learning to Predict Radiation Pneumonitis and Survival in NSCLC Patients Post-VMAT

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Cohort

2.3. VMAT Treatment

2.4. Outcome Definition

2.5. ROI Delineation

2.6. Feature Extraction

2.7. Feature Selection

2.8. Literature-Guided Model Choice

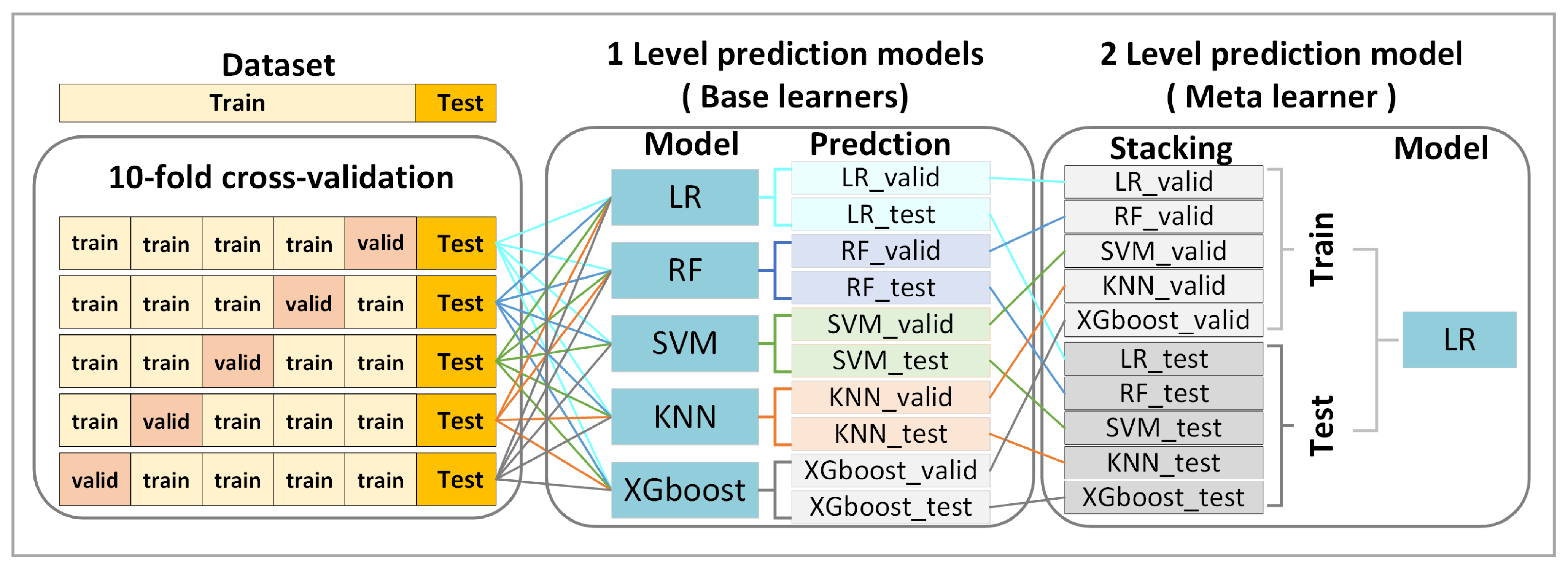

2.9. Ensemble Stacking

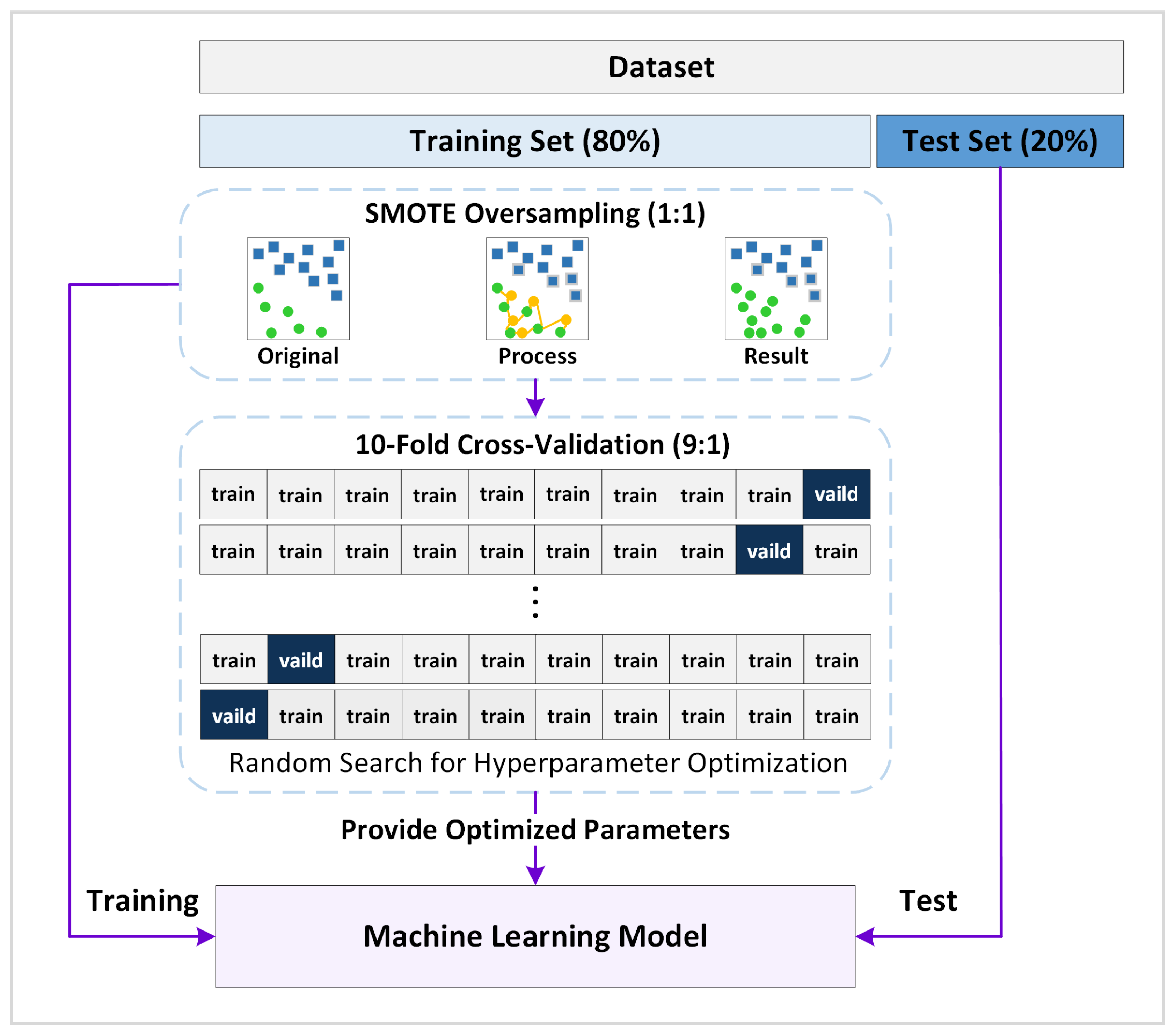

2.10. Model Training and Evaluation

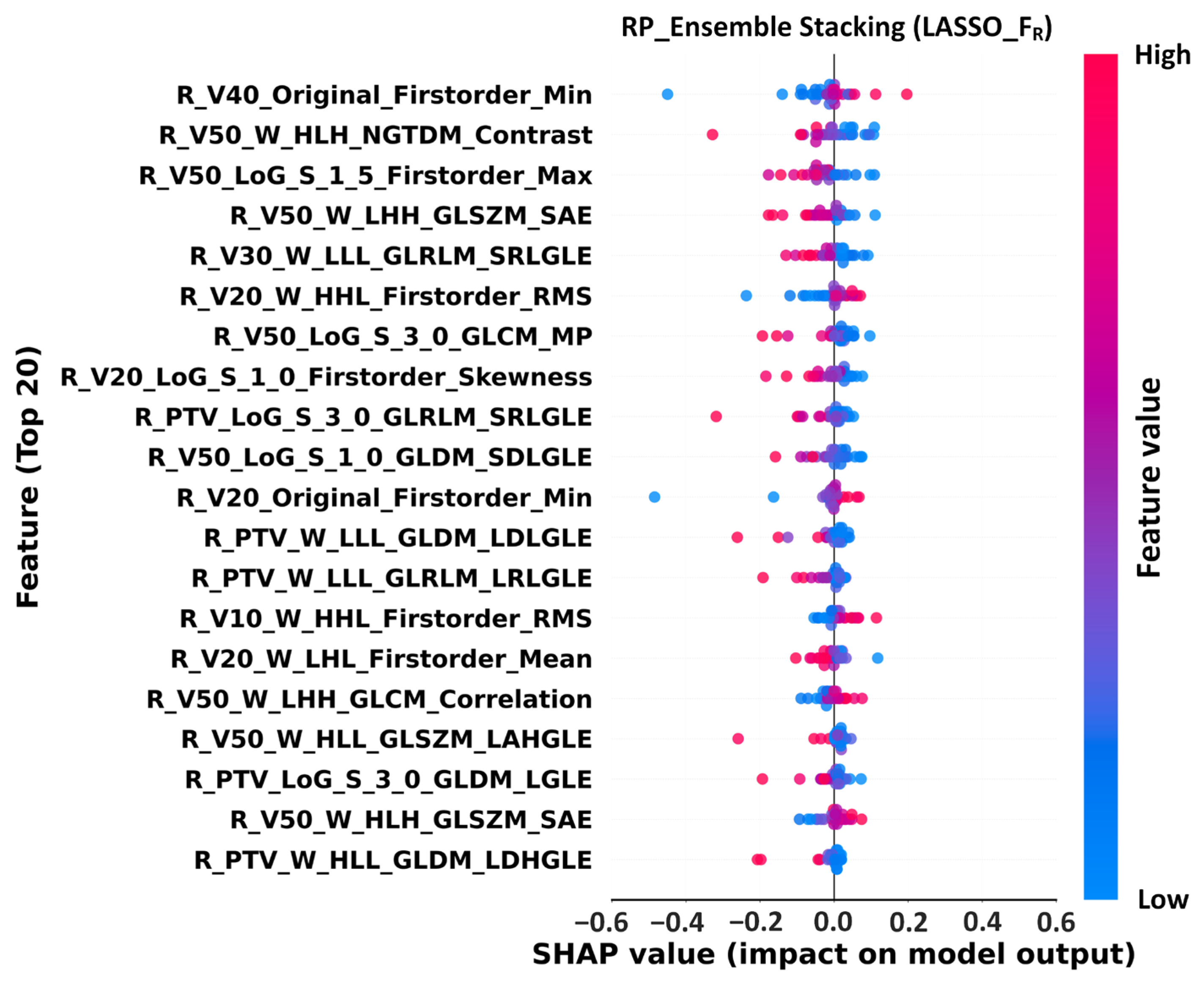

2.11. SHAP Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Feature Extraction and Selection

3.3. Model Performance Evaluation

3.4. Feature Importance Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, S.; Zheng, R.; Li, J.; Zeng, H.; Li, L.; Chen, R.; Sun, K.; Han, B.; Bray, F.; Wei, W. Global, regional, and national lifetime risks of developing and dying from gastrointestinal cancers in 185 countries: A population-based systematic analysis of GLOBOCAN. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappa, C.; Mousa, S.A. Non-small cell lung cancer: Current treatment and future advances. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016, 5, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, M.; Doi, H.; Igeta, M.; Suzuki, H.; Kitajima, K.; Tanooka, M.; Ishida, T.; Wakayama, T.; Yokoi, T.; Kuribayashi, K.; et al. Radiation pneumonitis after volumetric modulated arc therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 5793–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imano, N.; Kimura, T.; Kawahara, D.; Nishioka, R.; Fukumoto, W.; Kawano, R.; Kubo, K.; Katsuta, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Nishibuchi, I.; et al. Potential benefits of volumetric modulated arc therapy to reduce the incidence of ≥grade 2 radiation pneumonitis in radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 51, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, M.; Xia, B.; Ma, S. Radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer treated with volumetric modulated arc therapy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranwala, R.; Roughead, E.E.; Calabretto, J.-P.; Andrade, A.Q. Navigating Explainable Ai in Healthcare: A Taxonomic Guide for Clinical Decision Support Systems. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, K.; Morishita, S.; Nakano, J.; Inoue, J.; Okayama, T.; Suzuki, K.; Tanaka, T.; Fukushima, T. Relationship between quality of life before treatment and survival in patients with hematological malignancies: A meta-analysis. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2025, 71, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Timmeren, J.E.; Cester, D.; Tanadini-Lang, S.; Alkadhi, H.; Baessler, B. Radiomics in medical imaging—“how-to” guide and critical reflection. Insights Imaging 2020, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Hagiwara, Y.; Sudarshan, V.K.; Chan, W.Y.; Ng, K.H. Towards precision medicine: From quantitative imaging to radiomics. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 2018, 19, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Teng, X.; Huang, Y.-H.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Sun, J.; Dong, Y. Comparative Analysis of Repeatability in CT Radiomics and Dosiomics Features under Image Perturbation: A Study in Cervical Cancer Patients. Cancers 2024, 16, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, D.; Wang, H.X.; Li, Y.F.; Nguyen, T.N. Explainable artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 3503–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Rad, P. Opportunities and challenges in explainable artificial intelligence (xai): A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Zhu, X.-z.; Lee, T.-F.; Feng, P.-b.; Xu, J.-h.; Qian, P.-d.; Zhang, L.-f.; He, X.; Huang, S.-f.; Zhang, Y.-q. LASSO-based NTCP model for radiation-induced temporal lobe injury developing after intensity-modulated radiotherapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Yi, G.; Li, X.; Yi, B.; Bao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Z. Predicting radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer using machine learning and multimodal features: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, T.; Geyer, P.; Appold, S. The mean lung dose (MLD) Predictive criterion for lung damage? Strahlenther. Onkol. 2015, 191, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Cheng, D.; Ni, W.; Ai, Y.; Yu, X.; Tan, N.; Wu, J.; Fu, W.; Li, C.; Xie, C. Multi-omics deep learning for radiation pneumonitis prediction in lung cancer patients underwent volumetric modulated arc therapy. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 254, 108295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, D.; Kong, Y.; Huang, J.; Han, S. Radiation Pneumonitis Prediction Using Dual-Modal Data Fusion Based on Med3D Transfer Network. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2025, 38, 2085–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, A.; Yang, H.; Zhang, G.; Ma, J.; Ye, S.; Ge, S. Multicenter development of a deep learning radiomics and dosiomics nomogram to predict radiation pneumonia risk in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, J.L.; Warrington, A.P. Commissioning of volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009, 73, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, S.L.; Jin, H.; Wei, X.; Wang, S.; Martel, M.K.; Komaki, R.; Liu, H.H.; Mohan, R.; Chen, Y.; Cox, J.D. Impact of toxicity grade and scoring system on the relationship between mean lung dose and risk of radiation pneumonitis in a large cohort of patients with non–small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 77, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, M.; Tan, A.; Fisher, R.; Mac Manus, M.; Wirth, A.; Ball, D. Dose-volume histogram analysis as predictor of radiation pneumonitis in primary lung cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 61, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, A.; Vallières, M.; Abdalah, M.A.; Aerts, H.J.; Andrearczyk, V.; Apte, A.; Ashrafinia, S.; Bakas, S.; Beukinga, R.J.; Boellaard, R. The image biomarker standardization initiative: Standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology 2020, 295, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.-F.; Chang, C.-H.; Chi, C.-H.; Liu, Y.-H.; Shao, J.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-W.; Yang, P.-Y.; Tseng, C.-D.; Chiu, C.-L.; Hu, Y.-C. Utilizing radiomics and dosiomics with AI for precision prediction of radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.-F.; Liu, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-H.; Chiu, C.-L.; Lin, C.-H.; Shao, J.-C.; Yen, Y.-C.; Lin, G.-Z.; Yang, J.; Tseng, C.-D. Development of a risk prediction model for radiation dermatitis following proton radiotherapy in head and neck cancer using ensemble machine learning. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, P.-J.; Chang, C.-H.; Wu, J.-J.; Liu, Y.-H.; Shiau, J.; Shih, H.-H.; Lin, G.-Z.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, T.-F. Improving prediction of complications post-proton therapy in lung cancer using large language models and meta-analysis. Cancer Control 2024, 31, 10732748241286749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-F.; Hsieh, Y.-W.; Yang, P.-Y.; Tseng, C.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Yang, J.; Chang, L.; Wu, J.-M.; Tseng, C.-D.; Chao, P.-J. Using meta-analysis and CNN-NLP to review and classify the medical literature for normal tissue complication probability in head and neck cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahiduzzaman, M.; Abdulrazak, L.F.; Ayari, M.A.; Khandakar, A.; Islam, S.R. A novel framework for lung cancer classification using lightweight convolutional neural networks and ridge extreme learning machine model with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 248, 123392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Hu, S.; Jia, B.; Tuo, B.; Sun, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z. Radiotherapy remodels the tumor microenvironment for enhancing immunotherapeutic sensitivity. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Chu, X.; Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Chen, L.; Deng, F.; Liang, Z.; Jing, D.; Zhou, R. A multiomics approach-based prediction of radiation pneumonia in lung cancer patients: Impact on survival outcome. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 8923–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kang, M.K.; Park, J.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, J.-C.; Park, S.-H. Deep-learning model prediction of radiation pneumonitis using pretreatment chest computed tomography and clinical factors. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 23, 15330338241254060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, G.; Gu, Y.; Hao, S.; Huang, C.; Xie, H.; Mi, W.; Zeng, Y. Artificial intelligence-assisted machine learning models for predicting lung cancer survival. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 12, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, H.; Chen, M.; Sang, W.; Lu, K.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yin, F.-F.; Yang, Z. A dual-radiomics model for overall survival prediction in early-stage NSCLC patient using pre-treatment CT images. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1419621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, L.J.; Mukherjee, S.; Cheruvu, K.; Krabak, C.; Rachala, R.; Ratnakaram, K.; Sharma, P.; Singh, M.; Yendamuri, S. Exploring the impact of the obesity paradox on lung cancer and other malignancies. Cancers 2022, 14, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioğlu, A. The effect of preprocessing filters on predictive performance in radiomics. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2022, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebers, F.J.; Wee, L.; Likitlersuang, J.; Mak, R.H.; Bitterman, D.S.; Huang, Y.; Dekker, A.; Aerts, H.J.; Kann, B.H. Artificial intelligence research in radiation oncology: A practical guide for the clinician on concepts and methods. BJR Open 2024, 6, tzae039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Bajardi, P.; Bologna, G.; Bonchi, F.; Cortellessa, G.; Dekker, A.; Fracasso, F.; Joore, M.; Paragios, N.; Rattay, T. PRE-ACT: Prediction of Radiotherapy side Effects using explainable AI for patient Communication and Treatment modification. J. Cancer Policy 2025, 43, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghir-Wojtkowiak, E.; Alfaro, J.; Zanzotto, F.M. Leveraging knowledge for explainable AI in personalized cancer treatment: Challenges and future directions. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1637195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.; Goh, Y.; Kwak, J. Challenges and opportunities to integrate artificial intelligence in radiation oncology: A narrative review. Ewha Med. J. 2024, 47, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total n = 168 (100%) | RP2+ n = 47 (28%) | Non-RP n = 121 (72%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.345 | |||

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 68.6 ± 11.1 (39–96) | 69.6 ± 10.8 (43–90) | 67.8 ± 11.1 (39–96) | |

| BMI | 0.174 | |||

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 23.6 ± 4.5 (9.6–40.3) | 24.4 ± 4.6 (9.6–34.4) | 23.4 ± 4.3 (13.7–40.3) | |

| Gender (%) | 0.315 | |||

| Male | 123 (73) | 37 (22) | 86 (51) | |

| Female | 45 (27) | 10 (6) | 35 (21) | |

| T-stage (%) | 0.686 | |||

| T1 | 31 (18) | 9 (5) | 22 (13) | |

| T2 | 54 (32) | 18 (11) | 36 (21) | |

| T3 | 35 (21) | 9 (5) | 26 (16) | |

| T4 | 48 (29) | 11 (7) | 37 (22) | |

| N-stage (%) | 0.422 | |||

| N0 | 54 (32) | 14 (8) | 40 (24) | |

| N1 | 21 (13) | 6 (3) | 15 (9) | |

| N2 | 63 (37) | 15 (9) | 48 (29) | |

| N3 | 30 (18) | 12 (7) | 18 (11) | |

| Chemotherapy (%) | 0.412 | |||

| YES | 142 (85) | 38 (23) | 104 (62) | |

| NO | 26 (15) | 9 (5) | 17 (10) |

| Characteristics | Total n = 118 (100%) | Survival n = 84 (71%) | Death n = 34 (29%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.595 | |||

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 68.8 ± 11.6 (39–96) | 69.2 ± 10.9 (39–96) | 67.9 ± 13.2 (42–96) | |

| BMI | 0.022 | |||

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 23.5 ± 4.5 (9.6–40.3) | 24.1 ± 4.6 (9.6–40.3) | 22.0 ± 3.8 (13.9–30.4) | |

| Gender (%) | 0.170 | |||

| Male | 35 (30) | 28 (24) | 7 (6) | |

| Female | 83 (70) | 56 (47) | 27 (23) | |

| T-stage (%) | 0.134 | |||

| T1 | 24 (20) | 20 (17) | 4 (4) | |

| T2 | 42 (36) | 32 (27) | 10 (8) | |

| T3 | 25 (21) | 17 (14) | 8 (7) | |

| T4 | 27 (23) | 15 (13) | 12 (10) | |

| N-stage (%) | 0.144 | |||

| N0 | 39 (33) | 33 (28) | 6 (5) | |

| N1 | 15 (13) | 9 (7) | 6 (5) | |

| N2 | 42 (36) | 27 (23) | 15 (13) | |

| N3 | 22 (19) | 15 (13) | 7 (6) | |

| Chemotherapy (%) | 0.224 | |||

| YES | 101 (86) | 10 (8) | 7 (6) | |

| NO | 17 (14) | 74 (63) | 27 (23) |

| RP_Ensemble Stacking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Subsets | AUC (95% CI) | ACC (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Precision (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | F1 Score (95% CI) |

| FC | 0.68 (0.44–0.87) | 0.64 (0.44–0.81) | 0.77 (0.53–0.95) | 0.40 (0.10–0.75) | 0.51 (0.14–0.88) | 0.69 (0.46–0.89) | 0.44 (0.13–0.71) |

| FDVH | 0.54 (0.30–0.80) | 0.60 (0.41–0.78) | 0.79 (0.55–1.00) | 0.39 (0.14–0.67) | 0.64 (0.29–1.00) | 0.58 (0.36–0.81) | 0.47 (0.21–0.73) |

| FR_O | 0.39 (0.18–0.60) | 0.56 (0.38–0.71) | 0.70 (0.50–0.89) | 0.27 (0.00–0.57) | 0.30 (0.00–0.63) | 0.66 (0.45–0.84) | 0.27 (0.00–0.50) |

| FR_LoG | 0.57 (0.33–0.81) | 0.68 (0.53–0.82) | 0.76 (0.58–0.92) | 0.44 (0.11–0.80) | 0.40 (0.09–0.75) | 0.79 (0.62–0.95) | 0.41 (0.12–0.67) |

| FR_W | 0.70 (0.49–0.88) | 0.74 (0.59–0.88) | 0.80 (0.64–0.95) | 0.55 (0.25–0.89) | 0.50 (0.20–0.80) | 0.83 (0.67–0.96) | 0.51 (0.22–0.77) |

| FR | 0.91 (0.78–1.00) | 0.89 (0.74–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.73 (0.43–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.84 (0.67–1.00) | 0.83 (0.60–1.00) |

| FC+DVH | 0.42 (0.19–0.70) | 0.45 (0.26–0.63) | 0.68 (0.38–0.92) | 0.27 (0.07–0.53) | 0.51 (0.14–0.89) | 0.43 (0.21–0.67) | 0.34 (0.11–0.59) |

| FC+R | 0.91 (0.78–1.00) | 0.81 (0.67–0.96) | 0.85 (0.67–1.00) | 0.71 (0.33–1.00) | 0.62 (0.25–1.00) | 0.89 (0.73–1.00) | 0.65 (0.31–0.91) |

| FDVH+R | 0.87 (0.73–0.98) | 0.78 (0.63–0.93) | 0.81 (0.62–0.95) | 0.67 (0.25–1.00) | 0.49 (0.14–0.86) | 0.90 (0.74–1.00) | 0.54 (0.20–0.83) |

| FC+DVH+R | 0.81 (0.62–0.96) | 0.78 (0.63–0.93) | 0.81 (0.62–0.95) | 0.67 (0.25–1.00) | 0.49 (0.14–0.86) | 0.90 (0.74–1.00) | 0.54 (0.20–0.83) |

| Survival_Ensemble Stacking | |||||||

| Feature Subsets | AUC (95% CI) | ACC (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Precision (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | F1 Score (95% CI) |

| FC | 0.74 (0.52–0.92) | 0.72 (0.54–0.88) | 0.82 (0.61–1.00) | 0.51 (0.17–0.86) | 0.58 (0.20–1.00) | 0.78 (0.56–0.94) | 0.53 (0.18–0.80) |

| FDVH | 0.50 (0.21–0.80) | 0.71 (0.50–0.88) | 0.78 (0.56–0.95) | 0.49 (0.00–1.00) | 0.43 (0.00–0.83) | 0.82 (0.63–1.00) | 0.44 (0.00–0.75) |

| FR_O | 0.83 (0.62–1.00) | 0.71 (0.54–0.88) | 0.86 (0.65–1.00) | 0.50 (0.18–0.83) | 0.72 (0.33–1.00) | 0.71 (0.47–0.92) | 0.58 (0.25–0.84) |

| FR_LoG | 0.85 (0.68–0.99) | 0.75 (0.58–0.92) | 0.83 (0.63–1.00) | 0.57 (0.17–1.00) | 0.58 (0.17–1.00) | 0.82 (0.63–1.00) | 0.55 (0.18–0.82) |

| FR_W | 0.92 (0.75–1.00) | 0.75 (0.54–0.92) | 0.87 (0.67–1.00) | 0.55 (0.20–0.89) | 0.72 (0.33–1.00) | 0.76 (0.56–0.94) | 0.61 (0.27–0.88) |

| FR | 0.97 (0.88–1.00) | 0.92 (0.79–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.77 (0.45–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.88 (0.71–1.00) | 0.86 (0.62–1.00) |

| FC+DVH | 0.74 (0.50–0.92) | 0.63 (0.42–0.79) | 0.75 (0.50–0.94) | 0.37 (0.00–0.75) | 0.43 (0.00–0.83) | 0.70 (0.50–0.92) | 0.39 (0.00–0.67) |

| FC+R | 0.96 (0.86–1.00) | 0.88 (0.75–1.00) | 0.89 (0.72–1.00) | 0.84 (0.50–1.00) | 0.73 (0.33–1.00) | 0.94 (0.81–1.00) | 0.76 (0.40–1.00) |

| FDVH+R | 0.92 (0.78–1.00) | 0.83 (0.67–0.96) | 0.94 (0.79–1.00) | 0.66 (0.33–1.00) | 0.86 (0.50–1.00) | 0.82 (0.63–1.00) | 0.73 (0.40–0.94) |

| FC+DVH+R | 0.93 (0.80–1.00) | 0.88 (0.75–1.00) | 0.89 (0.72–1.00) | 0.84 (0.50–1.00) | 0.73 (0.33–1.00) | 0.94 (0.81–1.00) | 0.76 (0.40–1.00) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, T.-F.; Tsai, L.; Tseng, P.-S.; Hsu, C.-C.; Chang-Chien, L.-C.; Shiau, J.-P.; Hsieh, Y.-W.; Yeh, S.-A.; Wuu, C.-S.; Lin, Y.-W.; et al. Using Radiomics and Explainable Ensemble Learning to Predict Radiation Pneumonitis and Survival in NSCLC Patients Post-VMAT. Life 2025, 15, 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111753

Lee T-F, Tsai L, Tseng P-S, Hsu C-C, Chang-Chien L-C, Shiau J-P, Hsieh Y-W, Yeh S-A, Wuu C-S, Lin Y-W, et al. Using Radiomics and Explainable Ensemble Learning to Predict Radiation Pneumonitis and Survival in NSCLC Patients Post-VMAT. Life. 2025; 15(11):1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111753

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Tsair-Fwu, Lawrence Tsai, Po-Shun Tseng, Chia-Chi Hsu, Ling-Chuan Chang-Chien, Jun-Ping Shiau, Yang-Wei Hsieh, Shyh-An Yeh, Cheng-Shie Wuu, Yu-Wei Lin, and et al. 2025. "Using Radiomics and Explainable Ensemble Learning to Predict Radiation Pneumonitis and Survival in NSCLC Patients Post-VMAT" Life 15, no. 11: 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111753

APA StyleLee, T.-F., Tsai, L., Tseng, P.-S., Hsu, C.-C., Chang-Chien, L.-C., Shiau, J.-P., Hsieh, Y.-W., Yeh, S.-A., Wuu, C.-S., Lin, Y.-W., & Chao, P.-J. (2025). Using Radiomics and Explainable Ensemble Learning to Predict Radiation Pneumonitis and Survival in NSCLC Patients Post-VMAT. Life, 15(11), 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111753