Polarized Light Microscopy-Based Quantification of Scleral Collagen Fiber Bundle Remodeling in the Lens-Induced Myopia Mouse Model

Abstract

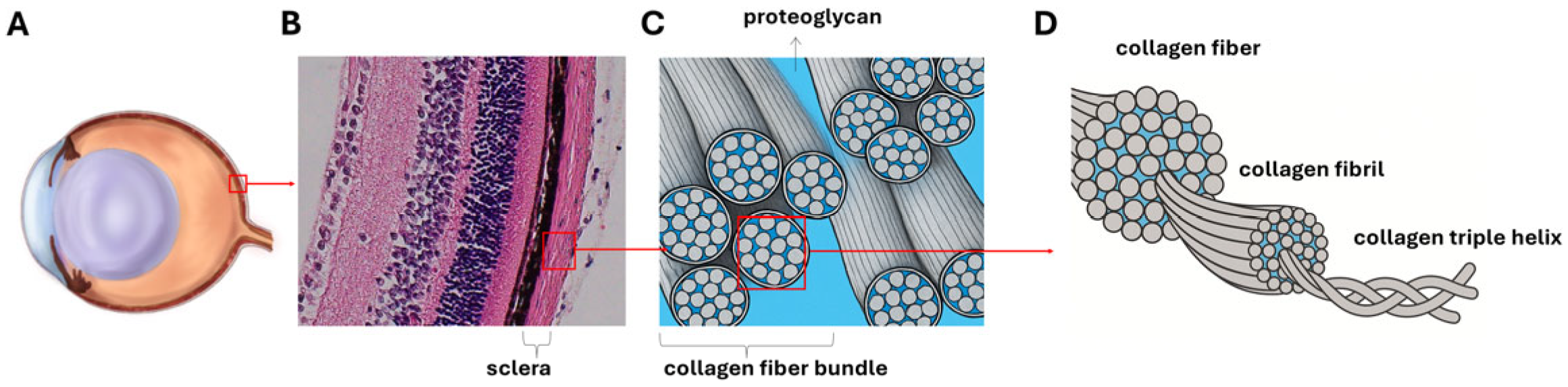

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

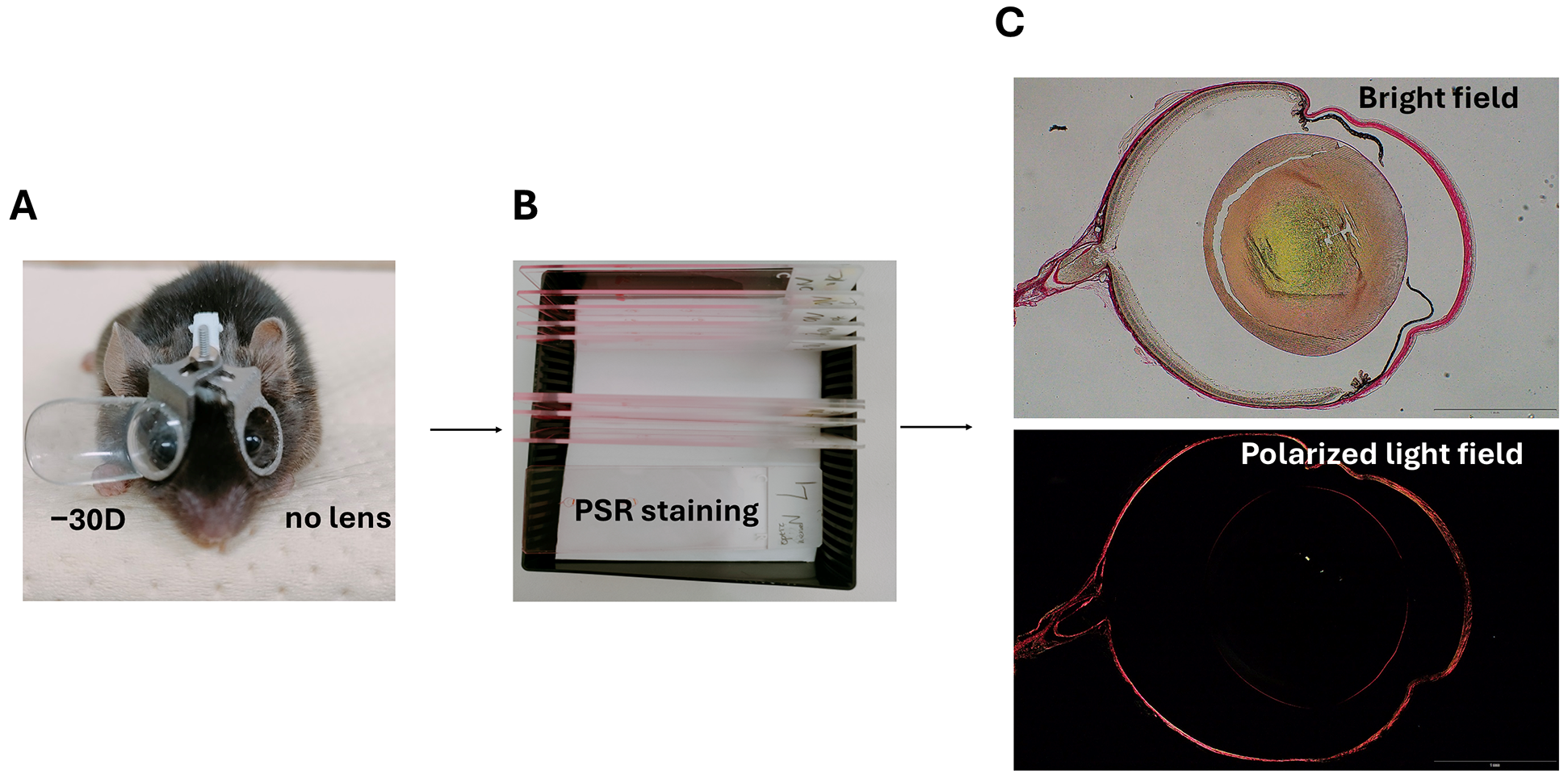

2.1. Animal Model

2.2. Specimen Staining and Image Acquisition

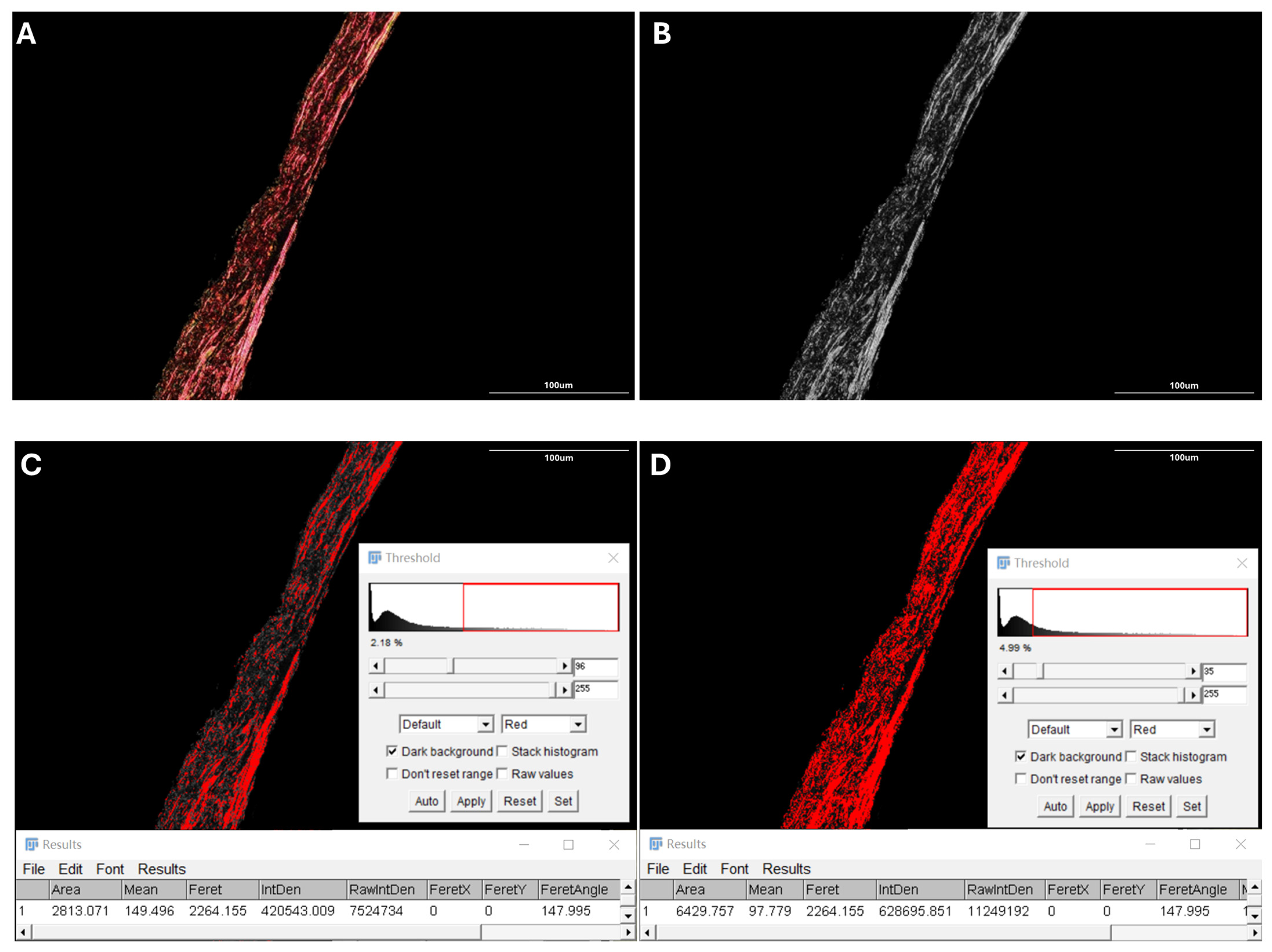

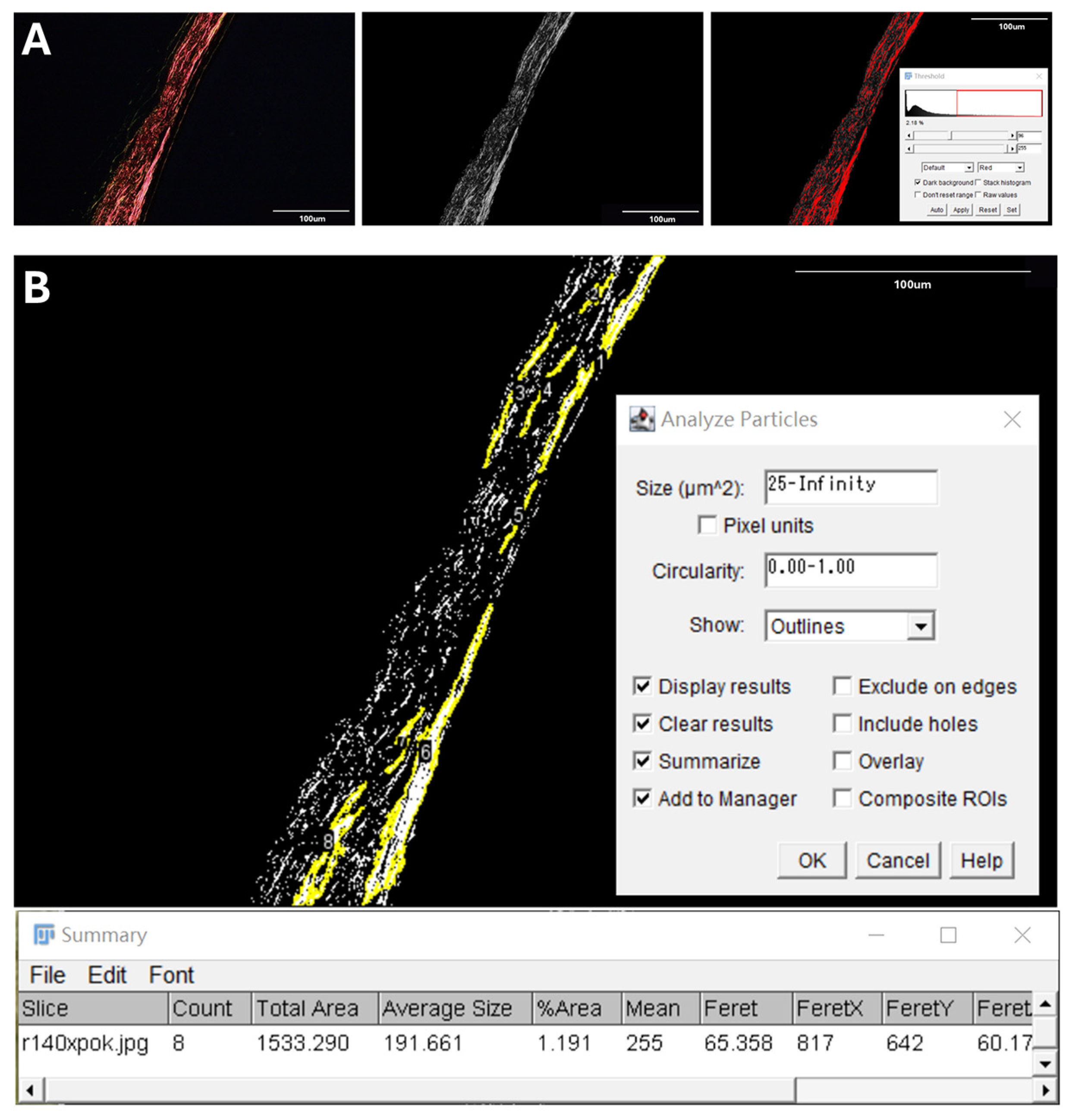

2.3. Quantification of Posterior Scleral Collagen Structure

2.4. Proportion of Collagen Fiber Bundles

2.5. Average Size of Collagen Fiber Bundles

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

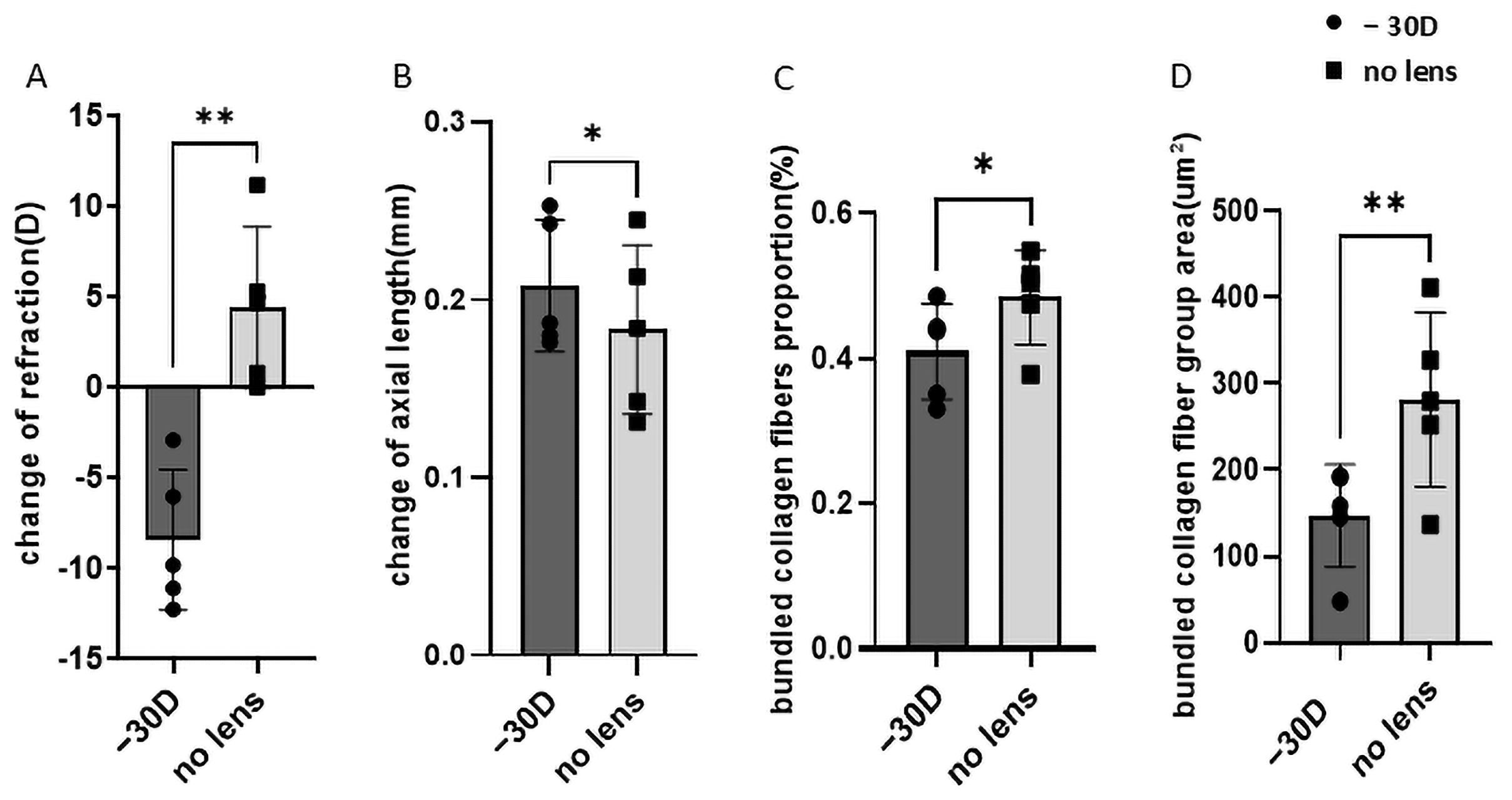

3.1. Refraction and Axial Length Alterations in Myopia

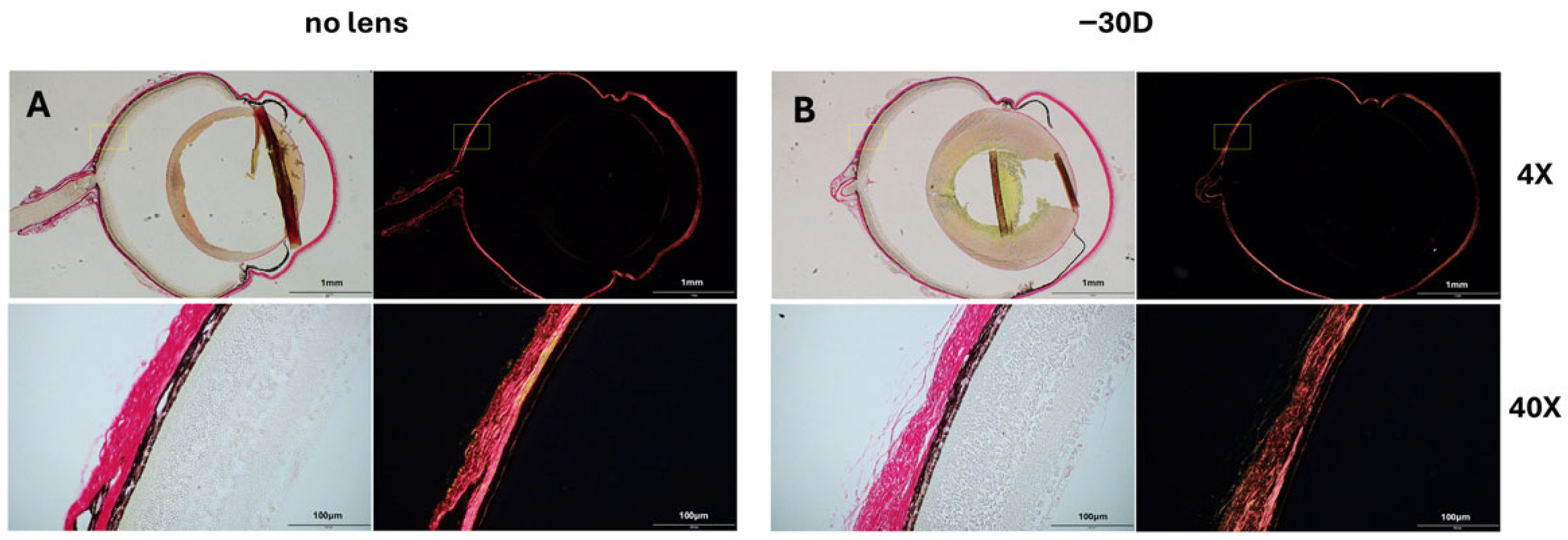

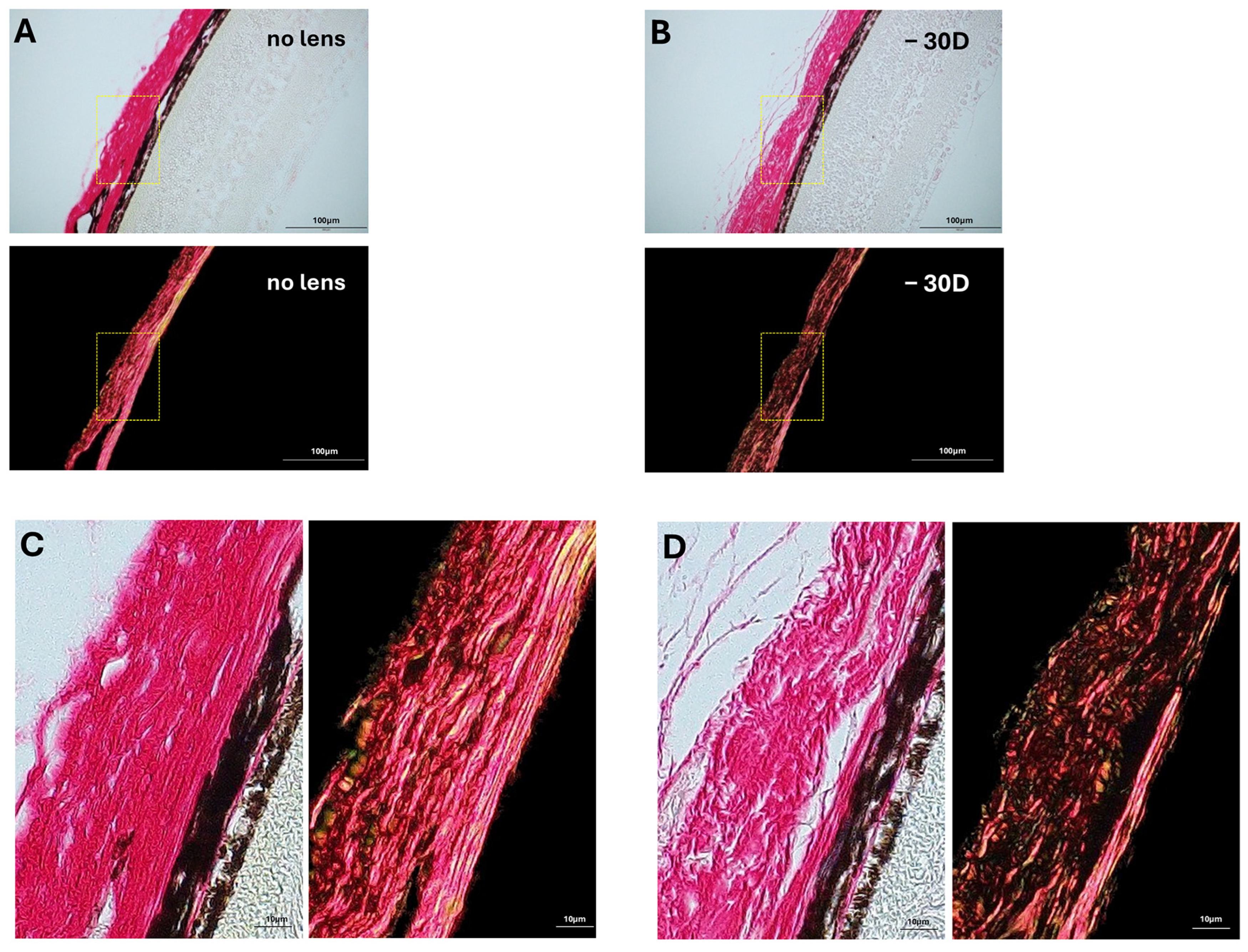

3.2. Collagen Fiber Bundle Alterations in Myopia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LIM | Lens-induced myopia |

| PLM | Polarized light microscopy |

| PSR | Picrosirius red |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| PS-OCT | Polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography |

| D | Diopter |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

References

- Holden, B.A.; Fricke, T.R.; Wilson, D.A.; Jong, M.; Naidoo, K.S.; Sankaridurg, P.; Wong, T.Y.; Naduvilath, T.J.; Resnikoff, S. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, I.G.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Saw, S.M. Myopia. Lancet 2012, 379, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rada, J.A.; Shelton, S.; Norton, T.T. The sclera and myopia. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 82, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBrien, N.A.; Gentle, A. Role of the sclera in the development and pathological complications of myopia. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2003, 22, 307–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Chen, W.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, Q.; Reinach, P.S.; Deng, L.; Ma, L.; Luo, S.; Srinivasalu, N.; Pan, M.; et al. Scleral hypoxia is a target for myopia control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E7091–E7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratzl, P. Collagen: Structure and Mechanics, an Introduction. In Collagen; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrien, N.A.; Jobling, A.I.; Gentle, A. Biomechanics of the sclera in myopia: Extracellular and cellular factors. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2009, 86, E23–E30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrien, N.A.; Lawlor, P.; Gentle, A. Scleral remodeling during the development of and recovery from axial myopia in the tree shrew. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 3713–3719. [Google Scholar]

- Siegwart, J.T., Jr.; Norton, T.T. Regulation of the mechanical properties of tree shrew sclera by the visual environment. Vis. Res. 1999, 39, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.T.; Rada, J.A. Reduced extracellular matrix in mammalian sclera with induced myopia. Vis. Res. 1995, 35, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.G.; Kim, W.; Choi, S.; Jin, K.H. Effects of scleral collagen crosslinking with different carbohydrate on chemical bond and ultrastructure of rabbit sclera: Future treatment for myopia progression. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, H.A.; Hohman, R.M.; Addicks, E.M.; Massof, R.W.; Green, W.R. Morphologic changes in the lamina cribrosa correlated with neural loss in open-angle glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1983, 95, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, H.A.; Addicks, E.M. Regional differences in the structure of the lamina cribrosa and their relation to glaucomatous optic nerve damage. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1981, 99, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platzl, C.; Kaser-Eichberger, A.; Benavente-Perez, A.; Schroedl, F. The choroid-sclera interface: An ultrastructural study. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkington, A.R.; Inman, C.B.; Steart, P.V.; Weller, R.O. The structure of the lamina cribrosa of the human eye: An immunocytochemical and electron microscopical study. Eye 1990, 4 Pt 1, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno-Matsui, K.; Igarashi-Yokoi, T.; Azuma, T.; Sugisawa, K.; Xiong, J.; Takahashi, T.; Uramoto, K.; Kamoi, K.; Okamoto, M.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Polarization-Sensitive OCT Imaging of Scleral Abnormalities in Eyes With High Myopia and Dome-Shaped Macula. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024, 142, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, J.; Zhou, N.; Yamanari, M.; Okamoto, M.; Sugisawa, K.; Takahashi, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Whorl-Like Collagen Fiber Arrangement Around Emissary Canals in the Posterior Sclera. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerig, C.; McFadden, S.; Hoang, Q.V.; Mamou, J. Biomechanical changes in myopic sclera correlate with underlying changes in microstructure. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 224, 109165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, L.C.; Bignolas, G.; Brentani, R.R. Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem. J. 1979, 11, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattouf, R.; Younes, R.; Lutomski, D.; Naaman, N.; Godeau, G.; Senni, K.; Changotade, S. Picrosirius red staining: A useful tool to appraise collagen networks in normal and pathological tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2014, 62, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R. Picrosirius red staining revisited. Acta Histochem. 2011, 113, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, L.; Whittaker, P. Collagen and picrosirius red staining: A polarized light assessment of fibrillar hue and spatial distribution. J. Morphol. Sci. 2005, 22, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira, L.C.; Montes, G.S.; Sanchez, E.M. The influence of tissue section thickness on the study of collagen by the Picrosirius-polarization method. Histochemistry 1982, 74, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Kurihara, T.; Kunimi, H.; Miyauchi, M.; Ikeda, S.I.; Mori, K.; Tsubota, K.; Torii, H.; Tsubota, K. A highly efficient murine model of experimental myopia. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Kurihara, T.; Ikeda, S.I.; Kunimi, H.; Mori, K.; Torii, H.; Tsubota, K. Inducement and Evaluation of a Murine Model of Experimental Myopia. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 143, e58822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogola, A.; Jan, N.J.; Brazile, B.; Lam, P.; Lathrop, K.L.; Chan, K.C.; Sigal, I.A. Spatial Patterns and Age-Related Changes of the Collagen Crimp in the Human Cornea and Sclera. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 2987–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, N.J.; Brazile, B.L.; Hu, D.; Grube, G.; Wallace, J.; Gogola, A.; Sigal, I.A. Crimp around the globe; patterns of collagen crimp across the corneoscleral shell. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 172, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.J.; Nguyen, D.D.; Lai, J.Y. Poly(l-Histidine)-Mediated On-Demand Therapeutic Delivery of Roughened Ceria Nanocages for Treatment of Chemical Eye Injury. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2302174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doube, M. Multithreaded two-pass connected components labelling and particle analysis in ImageJ. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ji, M.; Qin, Y.; Deng, T.; Jin, M. Morphologic and biochemical changes in the retina and sclera induced by form deprivation high myopia in guinea pigs. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.I.; Kurihara, T.; Jiang, X.; Miwa, Y.; Lee, D.; Serizawa, N.; Jeong, H.; Mori, K.; Katada, Y.; Kunimi, H.; et al. Scleral PERK and ATF6 as targets of myopic axial elongation of mouse eyes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moring, A.G.; Baker, J.R.; Norton, T.T. Modulation of glycosaminoglycan levels in tree shrew sclera during lens-induced myopia development and recovery. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 2947–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhou, Q.; Reinach, P.S.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.; Wen, Y.; Srinivasalu, N.; Qu, J.; Zhou, X. Cause and Effect Relationship between Changes in Scleral Matrix Metallopeptidase-2 Expression and Myopia Development in Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 1754–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Ikeda, S.I.; Yang, Y.; Jeong, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Negishi, K.; Tsubota, K.; Kurihara, T. Establishment of a novel ER-stress induced myopia model in mice. Eye Vis. 2023, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.K.; Berg, R.A.; Silver, F.H.; Garg, H.G. Effect of proteoglycans on type I collagen fibre formation. Biomaterials 1989, 10, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, J.C.; Suh, J.K.; Thomas, K.A.; Bellezza, A.J.; Burgoyne, C.F.; Hart, R.T. Viscoelastic characterization of peripapillary sclera: Material properties by quadrant in rabbit and monkey eyes. J. Biomech. Eng. 2003, 125, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grytz, R.; Fazio, M.A.; Libertiaux, V.; Bruno, L.; Gardiner, S.; Girkin, C.A.; Downs, J.C. Age- and race-related differences in human scleral material properties. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 8163–8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, J. Myopia development: Multifactorial interplay, molecular mechanisms and possible strategies. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1638184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Ikeda, S.-i.; Kang, L.; Ma, Z.; Negishi, K.; Tsubota, K.; Tomita, Y.; Gettinger, K.; Kurihara, T. Polarized Light Microscopy-Based Quantification of Scleral Collagen Fiber Bundle Remodeling in the Lens-Induced Myopia Mouse Model. Life 2025, 15, 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111743

Yang Y, Ikeda S-i, Kang L, Ma Z, Negishi K, Tsubota K, Tomita Y, Gettinger K, Kurihara T. Polarized Light Microscopy-Based Quantification of Scleral Collagen Fiber Bundle Remodeling in the Lens-Induced Myopia Mouse Model. Life. 2025; 15(11):1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111743

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yajing, Shin-ichi Ikeda, Longdan Kang, Ziyan Ma, Kazuno Negishi, Kazuo Tsubota, Yohei Tomita, Kate Gettinger, and Toshihide Kurihara. 2025. "Polarized Light Microscopy-Based Quantification of Scleral Collagen Fiber Bundle Remodeling in the Lens-Induced Myopia Mouse Model" Life 15, no. 11: 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111743

APA StyleYang, Y., Ikeda, S.-i., Kang, L., Ma, Z., Negishi, K., Tsubota, K., Tomita, Y., Gettinger, K., & Kurihara, T. (2025). Polarized Light Microscopy-Based Quantification of Scleral Collagen Fiber Bundle Remodeling in the Lens-Induced Myopia Mouse Model. Life, 15(11), 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111743