Nationwide Trends in Arthroscopic Knee Surgery and ACL Reconstruction in Romania, 2017–2023: Insights from a Seven-Year Health System Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Population Denominators and Incidence Calculation

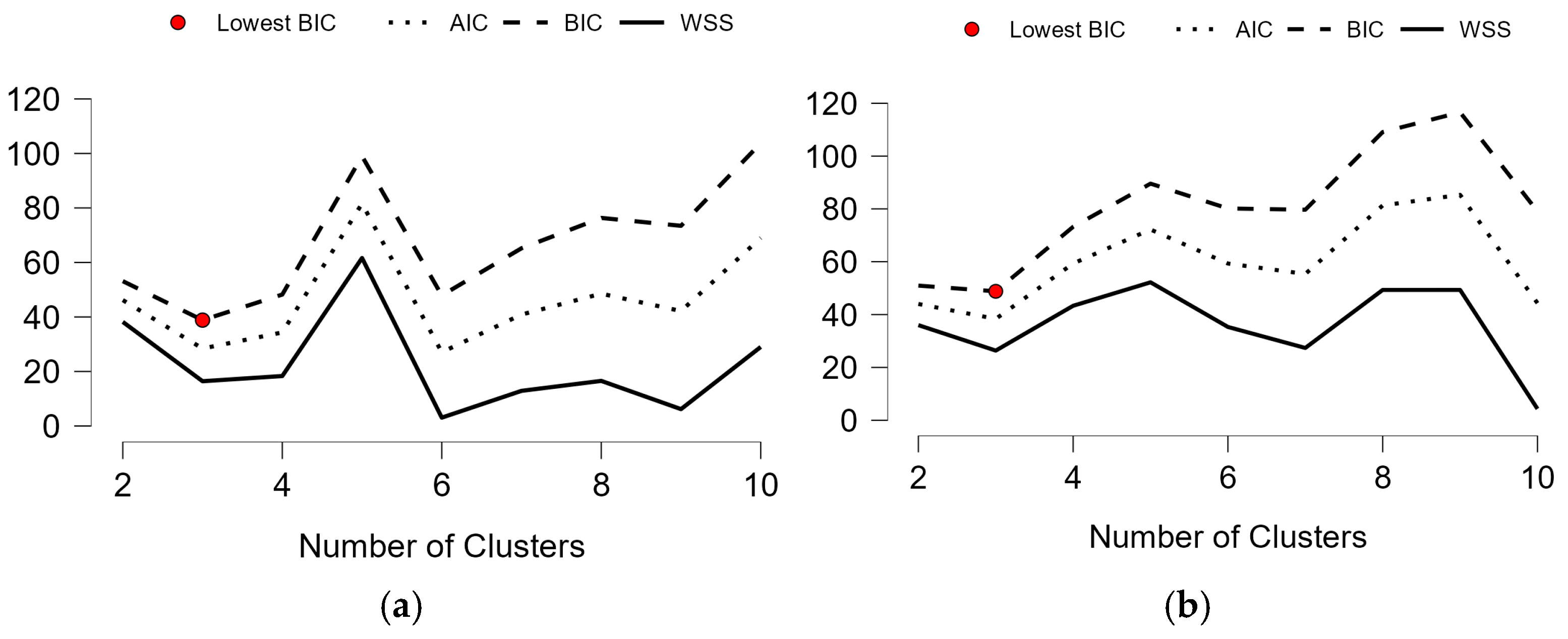

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

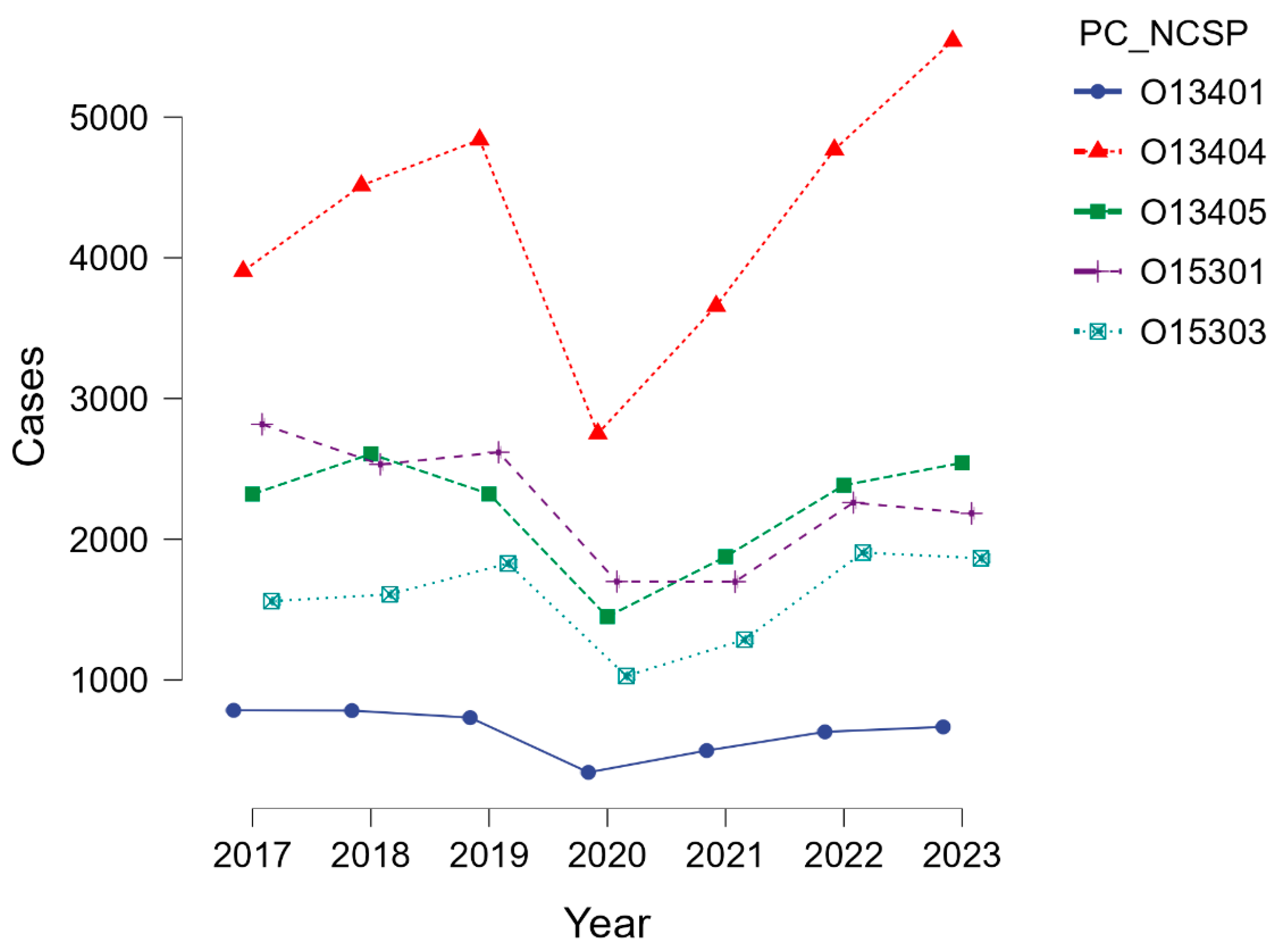

3.1. General Overview and Temporal Trend

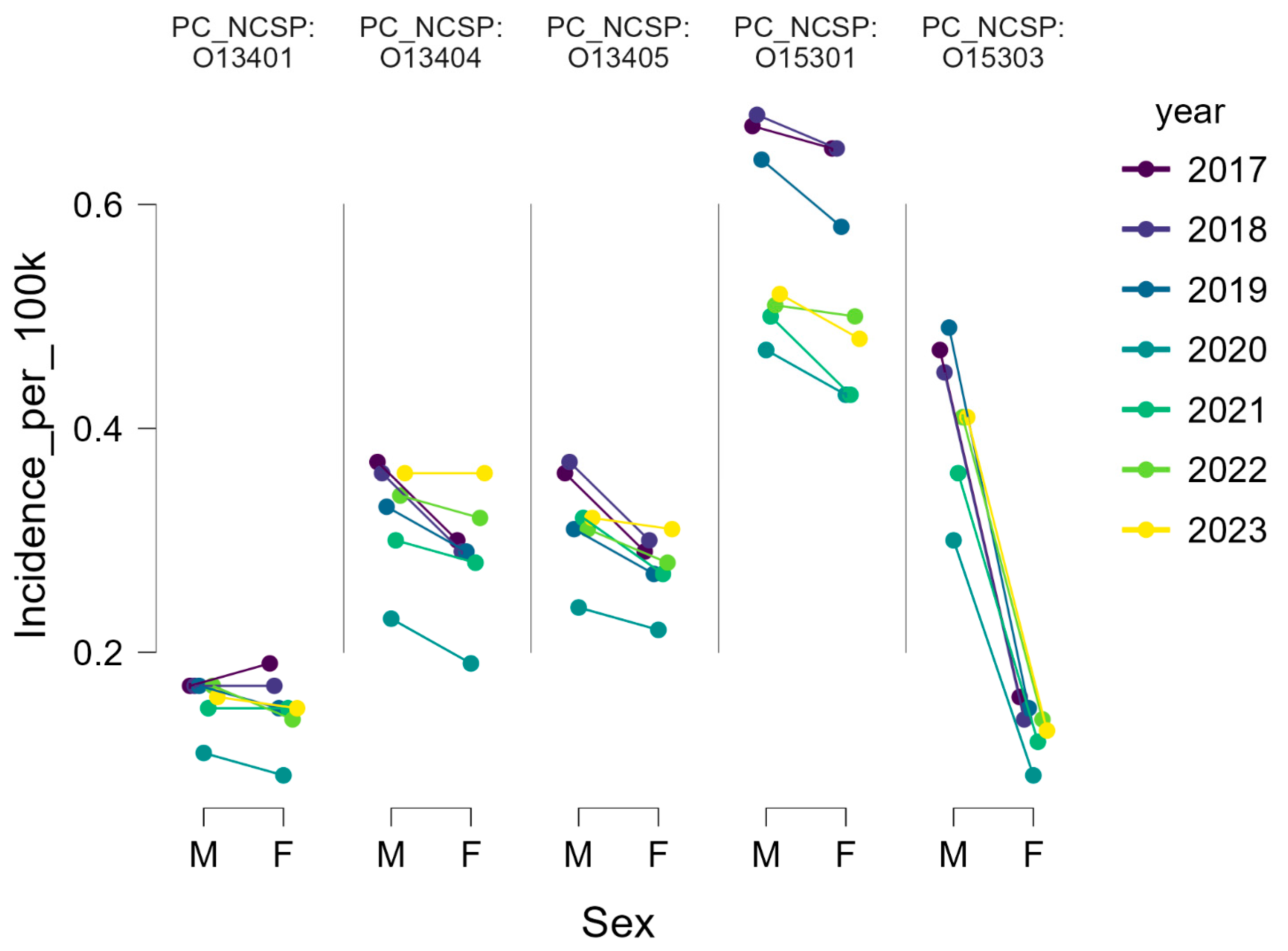

3.2. Sex Distribution

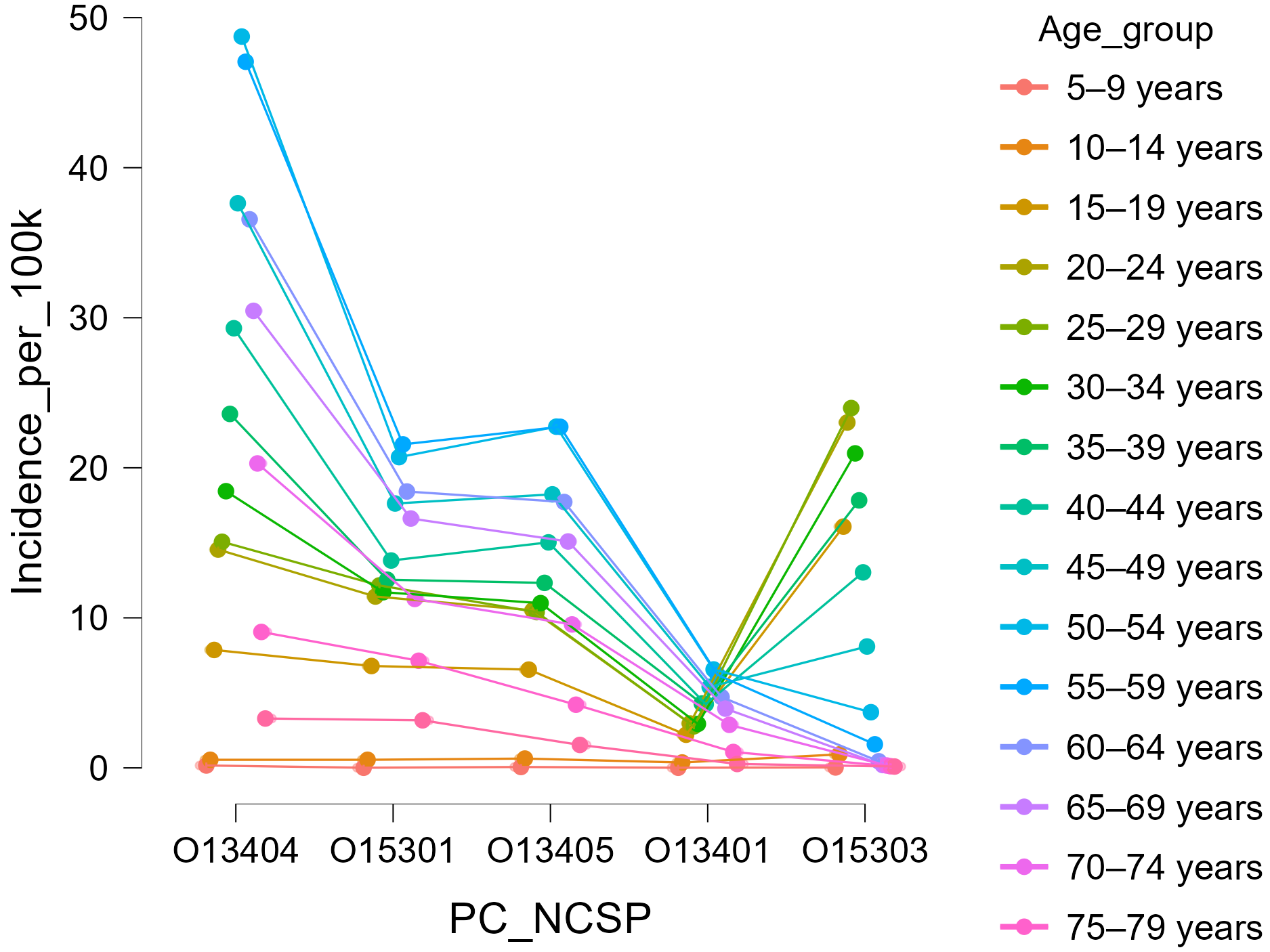

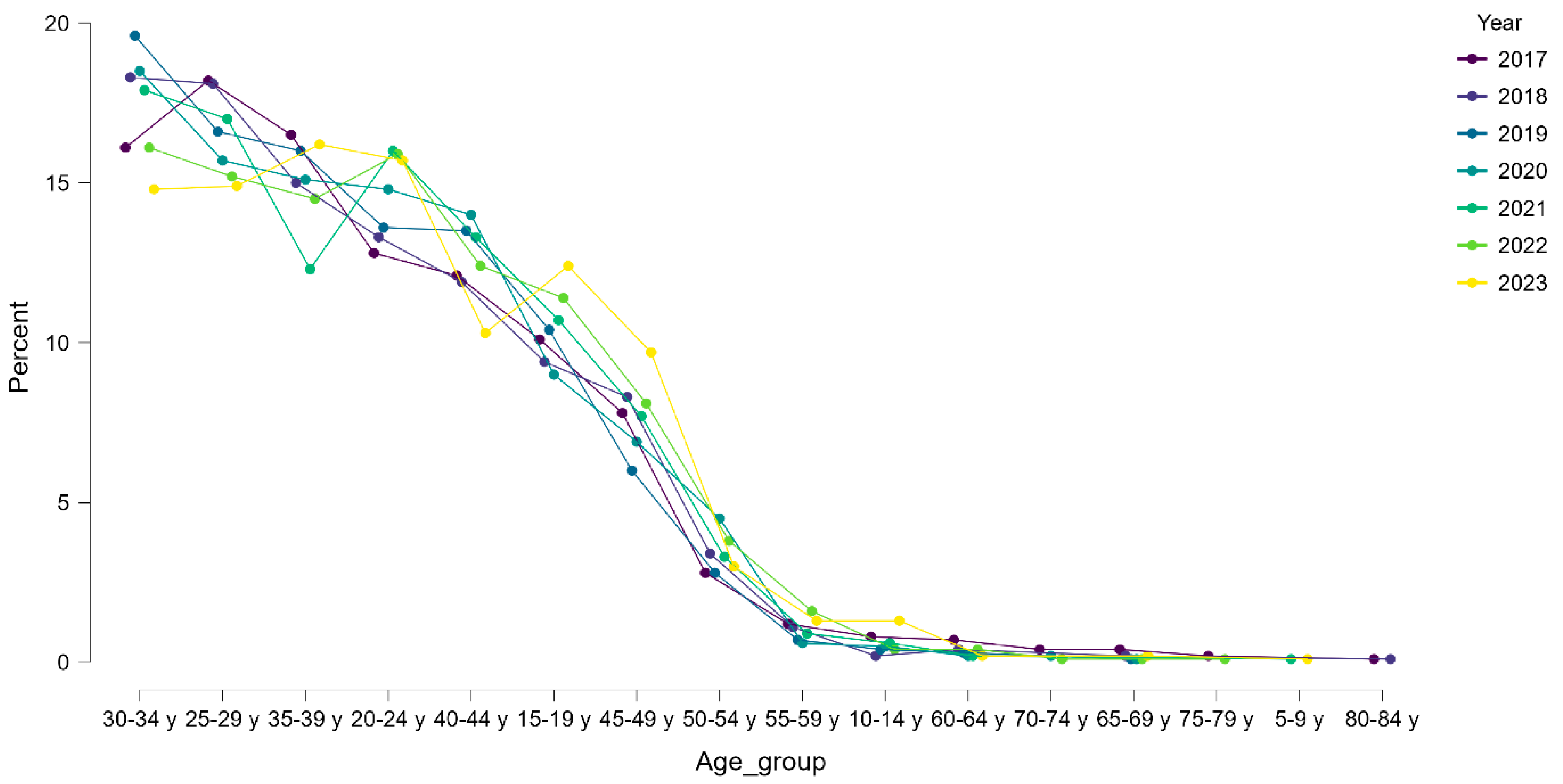

3.3. Age Distribution

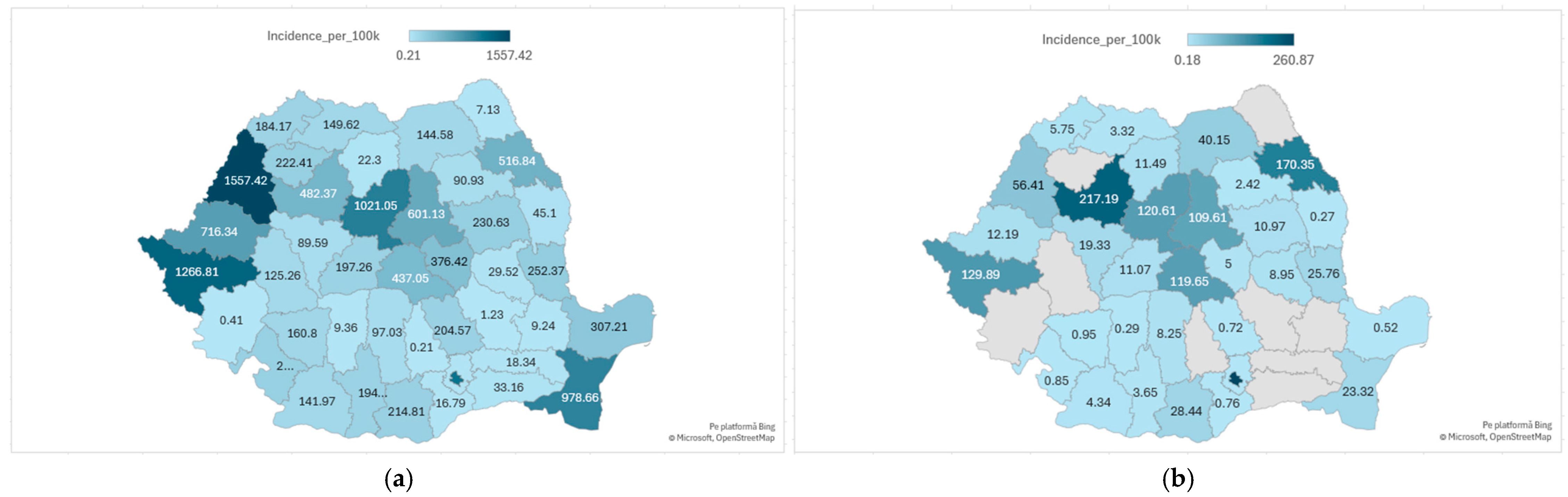

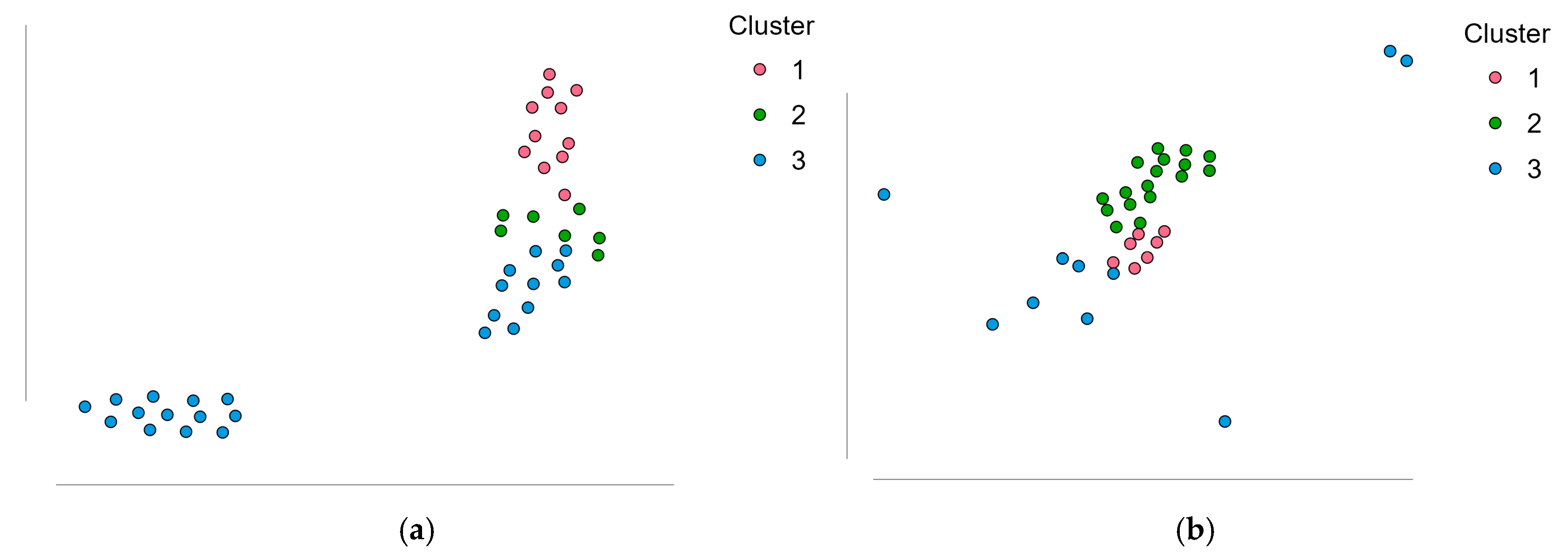

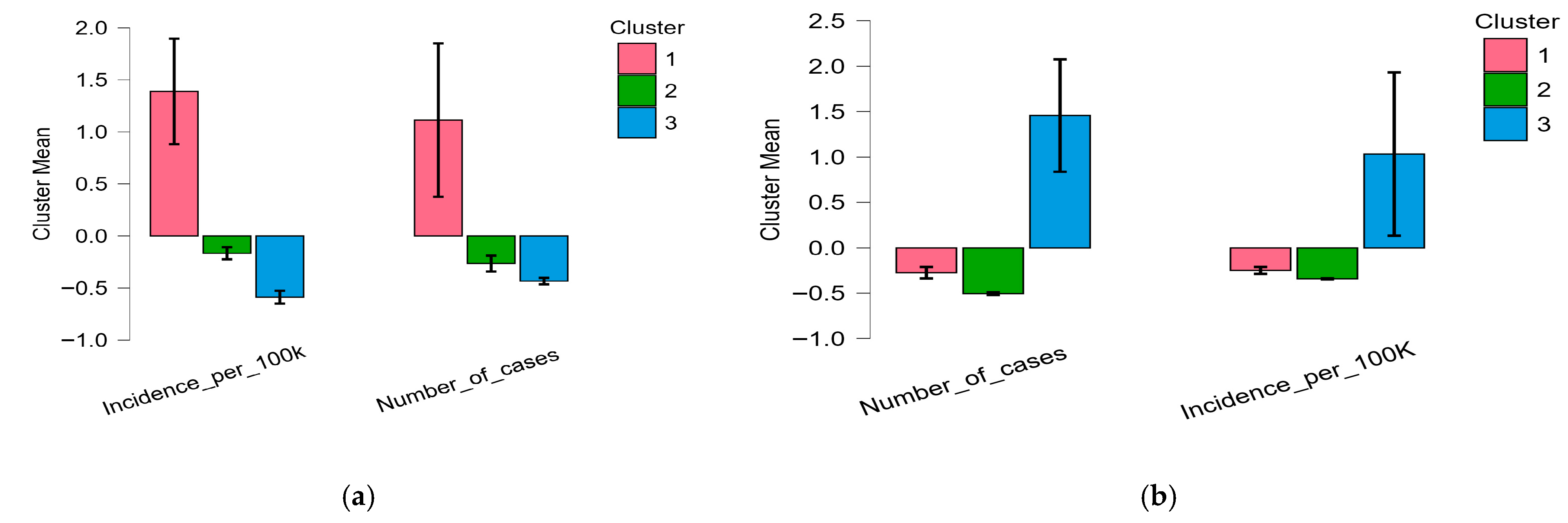

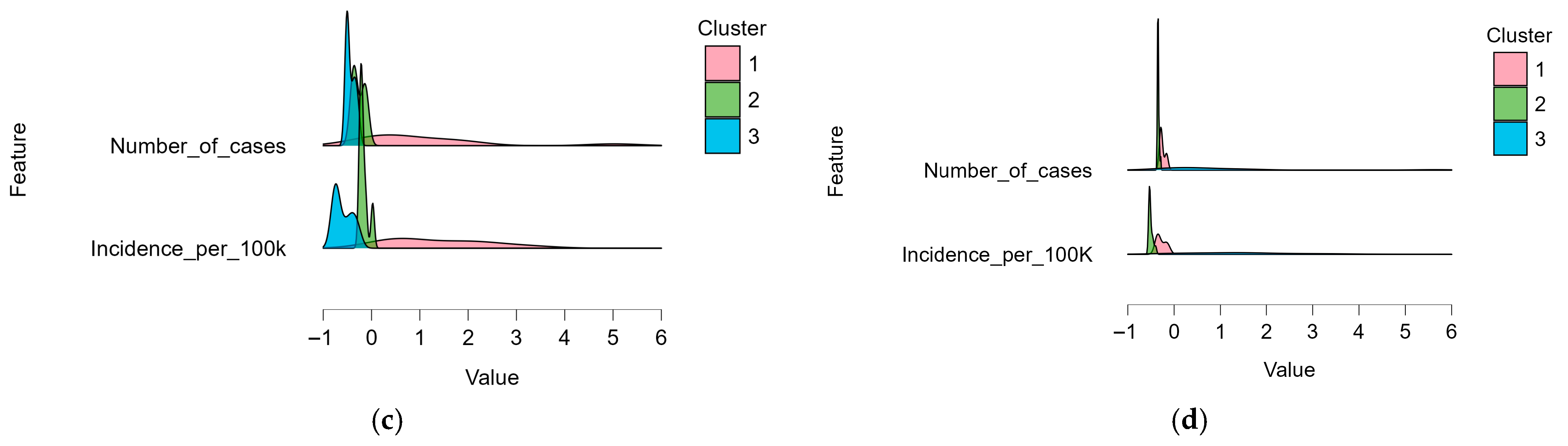

3.4. Regional Distribution

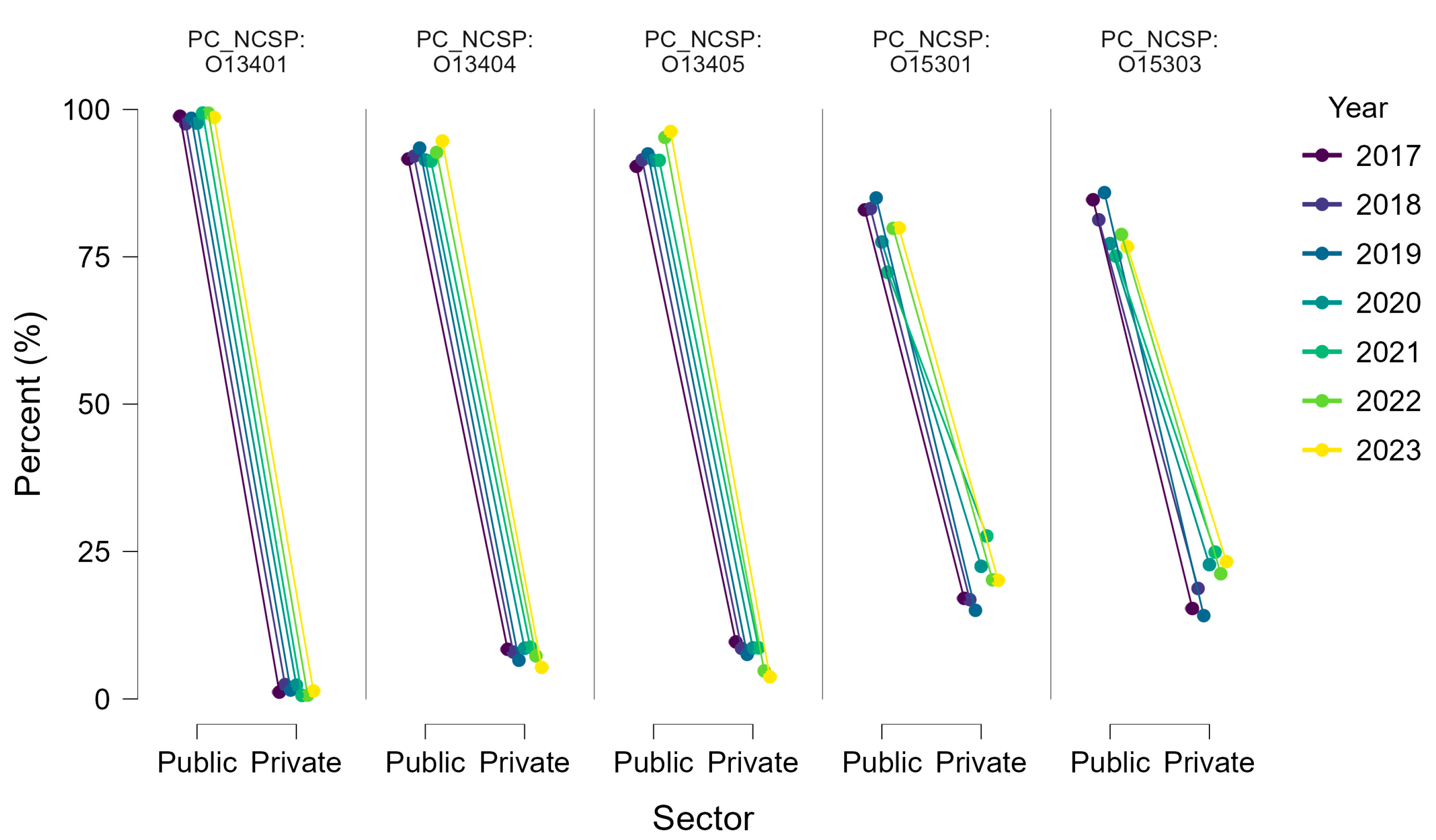

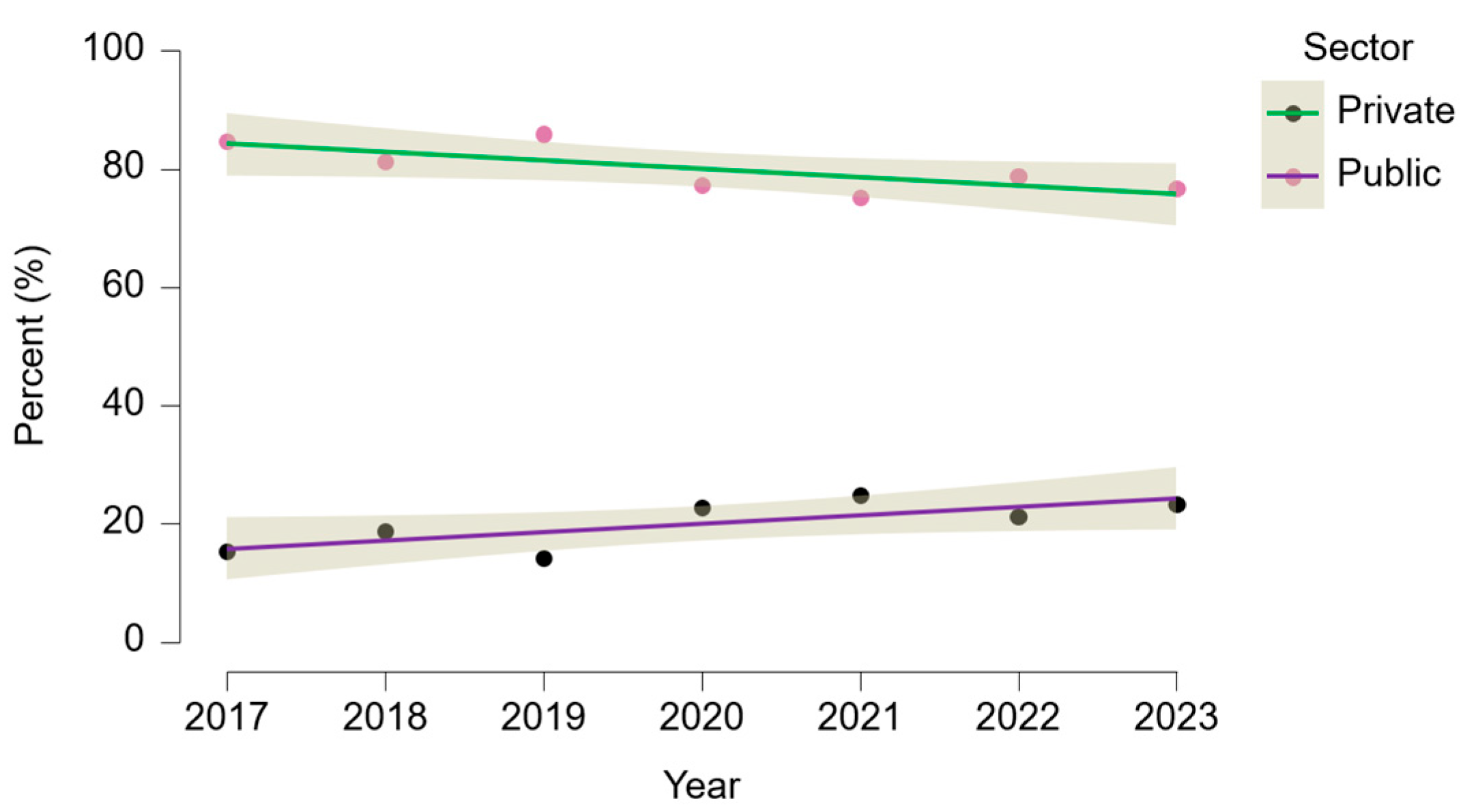

3.5. Public vs. Private Sector Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACL | Anterior cruciate ligament |

| AAOS | American academy of Orthopedic Surgeons |

| CNAS | Casa Națională de Asigurări de Sănătate (National Health Insurance House) |

| ESSKA | European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy |

| FIDELITY | Finnish degenerative meniscal lesion study |

| INSSE | Institutul Național de Statistică (Romanian National Institute of Statistics) |

| NCSP | Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures |

| PCL | Posterior cruciate ligament |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Motififard, M.; Akbari Aghdam, H.; Ravanbod, H.; Jafarpishe, M.S.; Shahsavan, M.; Daemi, A.; Mehrvar, A.; Rezvani, A.; Jamalirad, H.; Jajroudi, M.; et al. Demographic and injury characteristics as potential risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injuries: A multicentric cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristiani, R.; van de Bunt, F.; Kvist, J.; Stålman, A. High prevalence of associated injuries in anterior cruciate ligament tears: A detailed magnetic resonance imaging analysis of 254 patients. Skelet. Radiol. 2024, 53, 2417–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Masih, G.D.; Chander, G.; Bachhal, V. Delay in surgery predisposes to meniscal and chondral injuries in anterior cruciate ligament deficient knees. Indian J. Orthop. 2016, 50, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brophy, R.H.; Zeltser, D.; Wright, R.W.; Flanigan, D. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and concomitant articular cartilage injury: Incidence and treatment. Arthroscopy 2010, 26, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline; AAOS: Rosemont, IL, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/anterior-cruciate-ligament-injuries/aclcpg.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Lind, D.R.G.; Patil, R.S.; Amunategui, M.A.; DePhillipo, N.N. Evolution of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction & graft choice: A review. Ann. Jt. 2023, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Gao, L.; Zheng, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, C. Arthroscopic primary ACL repair versus autograft reconstruction: A comparative analysis of clinical outcomes. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 887522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, F.; Rovere, G.; Giustra, F.; Masoni, V.; Cassaro, S.; Capella, M.; Risitano, S.; Sabatini, L.; Lucenti, L.; Camarda, L. Advancements in anterior cruciate ligament repair—Current state of the art. Surgeries 2024, 5, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottomley, J.; Al-Dadah, O. Arthroscopic meniscectomy vs. meniscal repair: Comparison of clinical outcomes. Cureus 2023, 15, e44122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kwon, Y.-M.; Lee, C.; Kim, S.J.; Seo, Y.-J. Trends of pediatric anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery in Korea: Nationwide population-based study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooy, C.E.V.W.; Jakobsen, R.B.; Fenstad, A.M.; Persson, A.; Visnes, H.; Engebretsen, L.; Ekås, G.R. Major increase in incidence of pediatric ACL reconstructions from 2005 to 2021: A study from the Norwegian Knee Ligament Register. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 2891–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, A.; Carulli, C.; Innocenti, M.; Mosca, M.; Zaffagnini, S.; Bait, C. New trends in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review of national surveys of the last 5 years. Joints 2018, 6, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Bartlett, L.E.; Huyke-Hernandez, F.A.; Tauro, T.M.; Landman, F.; Cohn, R.M.; Sgaglione, N.A. Analysis of changing practice trends in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A multicenter, single-institution database analysis. Arthroscopy 2025, 41, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstein, V.E.; Ahiarakwe, U.; Haft, M.; Mikula, J.D.; Best, M.J. Decreasing incidence of partial meniscectomy and increasing incidence of meniscus preservation surgery from 2010 to 2020 in the United States. Arthroscopy 2025, 41, 1919–1927.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, C.; Pujol, N.; Pauly, V.; Beaufils, P.; Ollivier, M. Analysis of the trends in arthroscopic meniscectomy and meniscus repair procedures in France from 2005 to 2017. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2019, 105, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihn, H.E.; Prentice, H.A.; Maletis, G.B. Peripandemic utilization of primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in a United States-based integrated health care system, 2017–2023. Perm. J. 2025, 1–13, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, N.; de Sire, A.; Calafiore, D.; Agostini, F.; Lippi, L.; Curci, C.; Ferraro, F.; Bernetti, A.; Invernizzi, M.; Ammendolia, A. Impact of COVID-19 era on the anterior cruciate ligament injury rehabilitation: A scoping review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO). NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP); Version 1.16; NOMESCO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Population on 1 January by Age and Sex (demo_pjan). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_pjan (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics (INSSE). Tempo Online Database. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/en (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics (INSSE). 2021 Romanian Population and Housing Census. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Eurostat. Revision of the European Standard Population: Report of Eurostat’s Task Force; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5926869/KS-RA-13-028-EN.PDF (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Uivarășeanu, B.; Bungău, S.; Țiț, D.M.; Behl, T.; Maghiar, T.A.; Maghiar, O.; Pantiș, C.; Zaha, D.C.; Pătrașcu, J.M. Orthopedic surgery approach with uncemented metallic prosthesis in knee osteoarthritis increases the quality of life of young patients. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolan, G.A.; Răducan, I.D.; Uivarășeanu, B.; Țiț, D.M.; Bungau, G.S.; Radu, A.-F.; Furău, C.G. Nationwide epidemiology of hospitalized acute ACL ruptures in Romania: A 7-year analysis (2017–2023). Medicina 2025, 61, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbrojkiewicz, D.; Vertullo, C.; Grayson, J.E. Increasing rates of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young Australians, 2000–2015. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 208, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Y.R.; Sommerfeldt, M.; Voaklander, D. Increasing incidence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A 17-year population-based study in Alberta, Canada. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granan, L.P.; Forssblad, M.; Lind, M.; Engebretsen, L. The Scandinavian ACL Registries 2004–2007: Baseline Epidemiology. Acta Orthop. 2009, 80, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebensteiner, M.C.; Khosravi, I.; Hirschmann, M.T.; Heuberer, P.R.; The Board of the AGA-Society of Arthroscopy and Joint-Surgery; Thaler, M. Massive cutback in orthopaedic healthcare services due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2020, 28, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, R.S.; Shah, N.S.; Kanhere, A.P.; Hoge, C.G.; Thomson, C.G.; Grawe, B.M. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on sports-related injuries evaluated in US emergency departments. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671221075373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabr, A.; Fontalis, A.; Robinson, J.; Hage, W.; O’Leary, S.; Spalding, T.; Haddad, F.S. Ten-year results from the UK National Ligament Registry: Patient characteristics and factors predicting nonresponders for completion of outcome scores. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2024, 32, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Nagai, K.; Salvatore, G.; Cella, E.; Candela, V.; Cappelli, F.; Ciccozzi, M.; Denaro, V. Epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery in Italy: A 15-year nationwide registry study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaebjörnsson, T.; Hamrin Senorski, E.; Sundemo, D.; Svantesson, E.; Westin, O.; Musahl, V.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Samuelsson, K. Adolescents and female patients are at increased risk for contralateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A cohort study from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Register based on 17,682 patients. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 3938–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gornitzky, A.L.; Lott, A.; Yellin, J.L.; Fabricant, P.D.; Lawrence, J.T.; Ganley, T.J. Sport-Specific Yearly Risk and Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears in High School Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 2716–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder, A.M.; Culvenor, A.G.; King, M.G.; Haberfield, M.; Roughead, E.A.; Mastwyk, J.; Kemp, J.L.; Pazzinatto, M.F.; West, T.J.; Coburn, S.L.; et al. Let’s Talk about Sex (and Gender) after ACL Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Self-Reported Activity and Knee-Related Outcomes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Corchero, J.D.; Jiménez-Rubio, D. Waiting Times in Healthcare: Equal Treatment for Equal Need? Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvonen, R.; Paavola, M.; Malmivaara, A.; Itälä, A.; Joukainen, A.; Nurmi, H.; Kalske, J.; Järvinen, T.L.N.; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2515–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaufils, P.; Becker, R.; Kopf, S.; Englund, M.; Verdonk, R.; Ollivier, M.; Seil, R. Surgical management of degenerative meniscus lesions: The 2016 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemieniuk, R.A.C.; Harris, I.A.; Agoritsas, T.; Poolman, R.W.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Van de Velde, S.; Buchbinder, R.; Englund, M.; Lytvyn, L.; Quinlan, C.; et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: A clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2017, 357, j1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Graaf, V.A.; Noorduyn, J.C.A.; Willigenburg, N.W.; Butter, I.K.; de Gast, A.; Mol, B.W.; Saris, D.B.F.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Poolman, R.W.; ESCAPE Research Group. Effect of early surgery vs. physical therapy on knee function among patients with nonobstructive meniscal tears: The ESCAPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deviandri, R.; Daulay, M.C.; Iskandar, D.; Kautsar, A.P.; Lubis, A.M.T.; Postma, M.J. Health-Economic Evaluation of Meniscus Tear Treatments: A Systematic Review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, K.E.; Cevallos, N.; Jansson, H.L.; Lansdown, D.A.; Pandya, N.K.; Feeley, B.T.; Ma, C.B.; Zhang, A.L. Younger Patients Are More Likely to Undergo Arthroscopic Meniscal Repair and Revision Meniscal Surgery in a Large Cross-Sectional Cohort. Arthroscopy 2022, 38, 2875–2883.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadoo, S.; Keeling, L.E.; Engler, I.D.; Chang, A.Y.; Runer, A.; Kaarre, J.; Irrgang, J.J.; Hughes, J.D.; Musahl, V. Higher Odds of Meniscectomy Compared with Meniscus Repair in a Young Patient Population with Increased Neighbourhood Disadvantage. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Poland: Country Health Profile 2023 (State of Health in the EU); OECD Publishing: Paris, France; European Observatory: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/country-health-profiles/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Petre, I.; Barna, F.; Gurgus, D.; Tomescu, L.C.; Apostol, A.; Petre, I.; Furău, C.; Năchescu, M.L.; Bordianu, A. Analysis of the Healthcare System in Romania: A Brief Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, F.; Moldovan, L.; Bataga, T. A Comprehensive Research on the Prevalence and Evolution Trend of Orthopedic Surgeries in Romania. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancsik, K.; Bălăceanu, C.; Popescu, E.; Băicuș, B.; Ţăghiciu, O. Patient-Perceived Quality Assessment in Orthopedics and Traumatology Departments in Romania. Healthcare 2024, 12, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrin Senorski, E.; Svantesson, E.; Engebretsen, L.; Lind, M.; Forssblad, M.; Karlsson, J.; Samuelsson, K. Fifteen years of the Scandinavian knee ligament registries: Lessons, limitations and likely prospects. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beit Ner, E.; Nakamura, N.; Lattermann, C.; McNicholas, M.J. Knee Registries: State of the Art. J. ISAKOS 2022, 7, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J.L.; Akinrolie, O.; Loewen, H.; Coen, S.E. Gendered Sport Environments and Their Theoretical Contributions to Women’s Injury Risk, Experiences, and Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2025, 33, wspaj.2025-0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kirkwood, G. Outsourcing National Health Service Surgery to the Private Sector: Implications for Access, Equity and Sustainability. Health Policy 2025, 130, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, R.; Bittar, J.; Kaarre, J.; Zsidai, B.; Sansone, M.; Piussi, R.; Musahl, V.; Irrgang, J.; Samuelsson, K.; Senorski, E.H. Demographic and Surgical Characteristics in Patients Who Do Not Achieve Minimal Important Change in the KOOS Sport/Rec and QoL after ACL Reconstruction: A Comparative Study from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Registry. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e083803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.K.; Wastvedt, S.; Pareek, A.; Persson, A.; Visnes, H.; Fenstad, A.M.; Moatshe, G.; Wolfson, J.; Engebretsen, L. Predicting Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Revision: A Machine Learning Analysis Utilizing the Norwegian Knee Ligament Register. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2022, 104, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarre, J.; Zsidai, B.; Narup, E.; Horvath, A.; Svantesson, E.; Hamrin Senorski, E.; Grassi, A.; Musahl, V.; Samuelsson, K. Scoping Review on ACL Surgery and Registry Data. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2022, 15, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.; Shrivastav, S.; Gharpinde, M.R. Knee Arthroscopy in the Era of Precision Medicine: A Comprehensive Review of Tailored Approaches and Emerging Technologies. Cureus 2024, 16, e70932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.L.; Stannard, J.P.; Stoker, A.M.; Rucinski, K.; Crist, B.D.; Cook, C.R.; Crecelius, C.; Bozynski, C.C.; Kuroki, K.; Royse, L.A.; et al. A Bedside-to-Bench-to-Bedside Journey to Advance Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation towards Biologic Joint Restoration. J. Knee Surg. 2025, 38, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tueni, N.; Amirouche, F. Branding a New Technological Outlook for Future Orthopaedics. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NCSP Code | Procedure | Description |

|---|---|---|

| O13401 | Arthroscopic excision of meniscal rim or synovial plica | Limited partial meniscectomy or suprapatellar plica resection; often used for localized meniscal tears. |

| O13404 | Arthroscopic meniscectomy | Subtotal or total meniscectomy performed arthroscopically. |

| O13405 | Arthroscopic synovectomy | Resection of hypertrophic/inflamed synovium in chronic or proliferative synovitides. |

| O15301 | Arthroscopic reconstruction of the knee, unspecified | Generic code for ligament reconstructions not otherwise specified (e.g., posterior cruciate ligament, multi-ligament reconstructions). |

| O15303 | Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction with meniscal repair | Specific code for primary ACL reconstruction, usually combined with meniscal repair. |

| Year | O13401 n (I/100 K) | O13404 n (I/100 K) | O13405 n (I/100 K) | O15301 n (I/100 K) | O15303 n (I/100 K) | Total n (I/100 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 784 (3.99) | 3905 (19.88) | 2321 (11.82) | 2817 (14.34) | 1560 (7.94) | 11387 (57.97) |

| 2018 | 782 (4.00) | 4514 (23.11) | 2606 (13.34) | 2532 (12.96) | 1608 (8.23) | 12042 (61.65) |

| 2019 | 732 (3.77) | 4840 (24.93) | 2322 (11.96) | 2618 (13.48) | 1828 (9.42) | 12340 (63.56) |

| 2020 | 343 (1.77) | 2751 (14.23) | 1449 (7.50) | 1699 (8.79) | 1028 (5.32) | 7270 (37.61) |

| 2021 | 498 (2.59) | 3658 (19.05) | 1876 (9.77) | 1698 (8.84) | 1286 (6.70) | 9016 (46.95) |

| 2022 | 631 (3.31) | 4769 (25.04) | 2384 (12.52) | 2260 (11.87) | 1905 (10.00) | 11949 (62.75) |

| 2023 | 666 (3.50) | 5542 (29.08) | 2543 (13.35) | 2184 (11.46) | 1865 (9.79) | 12800 (67.18) |

| Procedure Cod | Male n (I/100 K) | Female n (I/100 K) |

|---|---|---|

| O13401 | 2198 (3.33) | 2238 (3.23) |

| O13404 | 15,239 (23.09) | 14,740 (21.3) |

| O13405 | 7917 (11.99) | 7584 (10.96) |

| O15301 | 7873 (11.93) | 7935 (11.47) |

| O15303 | 8226 (12.46) | 2854 (4.12) |

| Age Group | O13401 | O13404 | O13405 | O15301 | O15303 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| under 1 year | – | 1 (nan) | – | – | – |

| 1–4 years | – | – | – | 1 (nan) | – |

| 5–9 years | 1 (0.01) | 11 (0.16) | 4 (0.06) | 1 (0.01) | 2 (0.03) |

| 10–14 years | 27 (0.36) | 40 (0.54) | 46 (0.62) | 40 (0.54) | 67 (0.9) |

| 15–19 years | 162 (2.21) | 576 (7.86) | 480 (6.55) | 498 (6.79) | 1179 (16.08) |

| 20–24 years | 208 (2.96) | 1021 (14.55) | 737 (10.5) | 801 (11.42) | 1615 (23.02) |

| 25–29 years | 211 (2.77) | 1147 (15.07) | 790 (10.38) | 925 (12.16) | 1825 (23.98) |

| 30–34 years | 267 (2.93) | 1678 (18.44) | 999 (10.98) | 1065 (11.71) | 1907 (20.96) |

| 35–39 years | 405 (4.29) | 2227 (23.59) | 1164 (12.33) | 1184 (12.54) | 1683 (17.83) |

| 40–44 years | 447 (4.25) | 3080 (29.3) | 1580 (15.03) | 1453 (13.82) | 1370 (13.03) |

| 45–49 years | 580 (5.4) | 4044 (37.63) | 1959 (18.23) | 1894 (17.62) | 870 (8.09) |

| 50–54 years | 649 (6.56) | 4824 (48.74) | 2251 (22.74) | 2050 (20.71) | 367 (3.71) |

| 55–59 years | 483 (6.2) | 3663 (47.06) | 1769 (22.73) | 1678 (21.56) | 122 (1.57) |

| 60–64 years | 422 (4.72) | 3267 (36.56) | 1583 (17.72) | 1646 (18.42) | 39 (0.44) |

| 65–69 years | 335 (3.95) | 2582 (30.46) | 1279 (15.09) | 1409 (16.62) | 16 (0.19) |

| 70–74 years | 180 (2.87) | 1271 (20.29) | 599 (9.56) | 705 (11.26) | 10 (0.16) |

| 75–79 years | 48 (1.06) | 411 (9.06) | 191 (4.21) | 324 (7.14) | 5 (0.11) |

| 80–84 years | 9 (0.26) | 116 (3.29) | 54 (1.53) | 112 (3.17) | 3 (0.09) |

| over 85 | 2 (nan) | 20 (nan) | 16 (nan) | 22 (nan) | – |

| Age Group | Male | Female | Risk Ratio | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.55 |

| 25–29 | 26 | 41 | 1.27 | 0.78 | 2.08 |

| 30–34 | 745 | 434 | 1.63 | 1.46 | 1.82 |

| 35–39 | 1293 | 322 | 3.54 | 3.14 | 3.99 |

| 40–44 | 1542 | 283 | 4.18 | 3.71 | 4.72 |

| 45–49 | 1598 | 309 | 4.13 | 3.67 | 4.65 |

| 50–54 | 1282 | 401 | 2.94 | 2.63 | 3.29 |

| 55–59 | 936 | 434 | 2.01 | 1.78 | 2.27 |

| 60–64 | 539 | 331 | 1.63 | 1.41 | 1.88 |

| 65–69 | 174 | 193 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 1.13 |

| 70–74 | 57 | 65 | 0.88 | 0.60 | 1.29 |

| 75–79 | 21 | 18 | 1.17 | 0.65 | 2.10 |

| 80–84 | 6 | 10 | 0.65 | 0.25 | 1.66 |

| 20–24 | 3 | 7 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 1.63 |

| 25–29 | 2 | 3 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 4.00 |

| 30–34 | 1 | 3 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 3.18 |

| Age Group | ESP Weight | Total Incidence (/100 k) | Male Incidence (/100 k) | Female Incidence (/100 k) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–9 | 5500 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 10–14 | 5500 | 0.90 | 0.54 | 1.27 |

| 15–19 | 5500 | 16.08 | 20.54 | 11.51 |

| 20–24 | 6000 | 23.02 | 31.95 | 14.30 |

| 25–29 | 6000 | 23.98 | 34.13 | 13.99 |

| 30–34 | 6000 | 20.96 | 28.47 | 12.96 |

| 35–39 | 6000 | 17.83 | 24.21 | 11.22 |

| 40–44 | 6000 | 13.03 | 18.24 | 7.84 |

| 45–49 | 6000 | 8.09 | 11.31 | 5.06 |

| 50–54 | 6000 | 3.71 | 5.56 | 1.95 |

| 55–59 | 5000 | 1.57 | 2.35 | 0.76 |

| 60–64 | 5000 | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0.22 |

| 65–69 | 4000 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.09 |

| 70–74 | 3000 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.07 |

| 75–79 | 2000 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| 80–84 | 1000 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| Procedure Code | Public n (%) | Private n (%) | Total Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| O13401 | 3648 (98.5) | 55 (1.5) | 3703 |

| O13404 | 28,577 (92.3) | 2412 (7.7) | 30,989 |

| O13405 | 12,384 (92.0) | 1070 (8.0) | 13,454 |

| O15301 | 9238 (80.1) | 2294 (19.9) | 11,532 |

| O15303 | 8564 (82.2) | 1856 (17.8) | 10,420 |

| Total | 62,411 (89.1) | 7687 (10.9) | 70,098 |

| Country | Source Type | Numerator | Setting | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romania | CNAS database | All reported ACL reconstructions | Inpatient only (DRG data) | Includes public & private contracted hospitals |

| Australia | National registry | Surgical ACL reconstructions | Inpatient + day surgery | High reporting compliance |

| Canada | Hospital records | ACL procedures (ICD codes) | Inpatient + ambulatory | May vary by province |

| Nordic countries | National registries | ACL reconstructions | Mostly inpatient | Near-complete coverage; minor variation by country |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tolan, G.A.; Precup, C.V.; Uivaraseanu, B.; Tit, D.M.; Bungau, G.S.; Radu, A.-F.; Furau, C.G. Nationwide Trends in Arthroscopic Knee Surgery and ACL Reconstruction in Romania, 2017–2023: Insights from a Seven-Year Health System Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111734

Tolan GA, Precup CV, Uivaraseanu B, Tit DM, Bungau GS, Radu A-F, Furau CG. Nationwide Trends in Arthroscopic Knee Surgery and ACL Reconstruction in Romania, 2017–2023: Insights from a Seven-Year Health System Analysis. Life. 2025; 15(11):1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111734

Chicago/Turabian StyleTolan, Gloria Alexandra, Cris Virgiliu Precup, Bogdan Uivaraseanu, Delia Mirela Tit, Gabriela S. Bungau, Andrei-Flavius Radu, and Cristian George Furau. 2025. "Nationwide Trends in Arthroscopic Knee Surgery and ACL Reconstruction in Romania, 2017–2023: Insights from a Seven-Year Health System Analysis" Life 15, no. 11: 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111734

APA StyleTolan, G. A., Precup, C. V., Uivaraseanu, B., Tit, D. M., Bungau, G. S., Radu, A.-F., & Furau, C. G. (2025). Nationwide Trends in Arthroscopic Knee Surgery and ACL Reconstruction in Romania, 2017–2023: Insights from a Seven-Year Health System Analysis. Life, 15(11), 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111734