A Two-Hit Model of Executive Dysfunction: Simulated Galactic Cosmic Radiation Primes Latent Deficits Revealed by Sleep Fragmentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Regulatory Compliance

2.2. Rat Demographics, Husbandry, Experimental Timeline, and Exercise Regimen

2.3. Irradiation Procedure

2.4. Associative Recognition Memory and Interference Touchscreen Task (ARMIT) Screening

2.4.1. Stimulus Response Training (SRT)

2.4.2. ARMIT Performance Evaluation

ARMIT Error Classification

Sleep Fragmentation and ARMIT Retesting

2.5. Statistical Methods

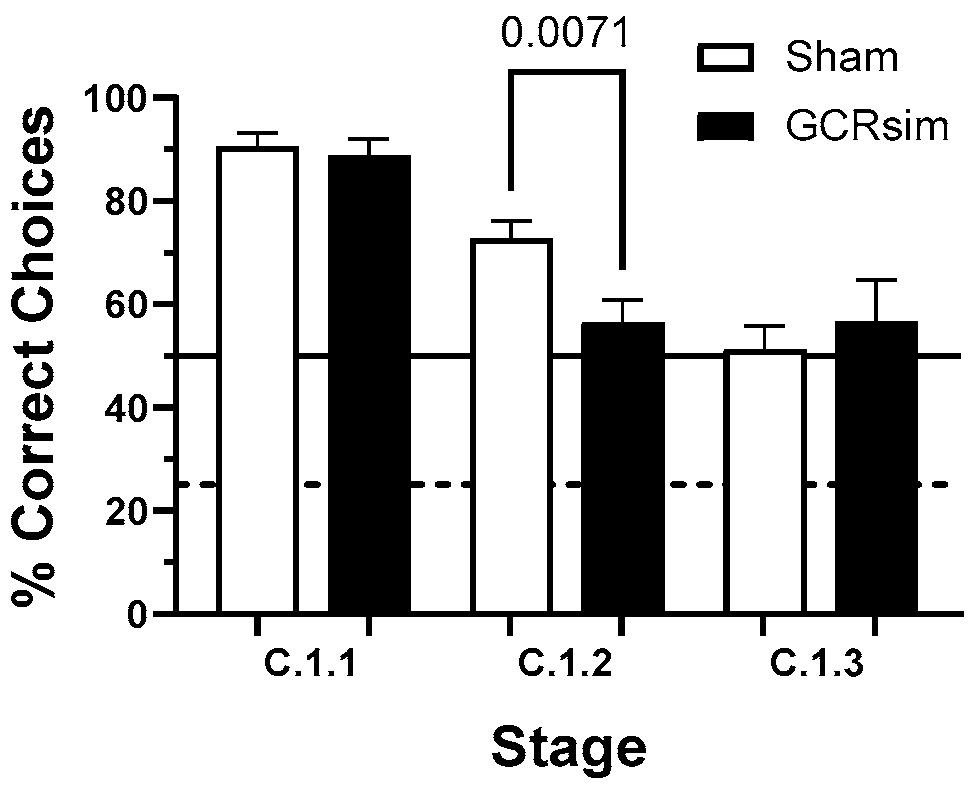

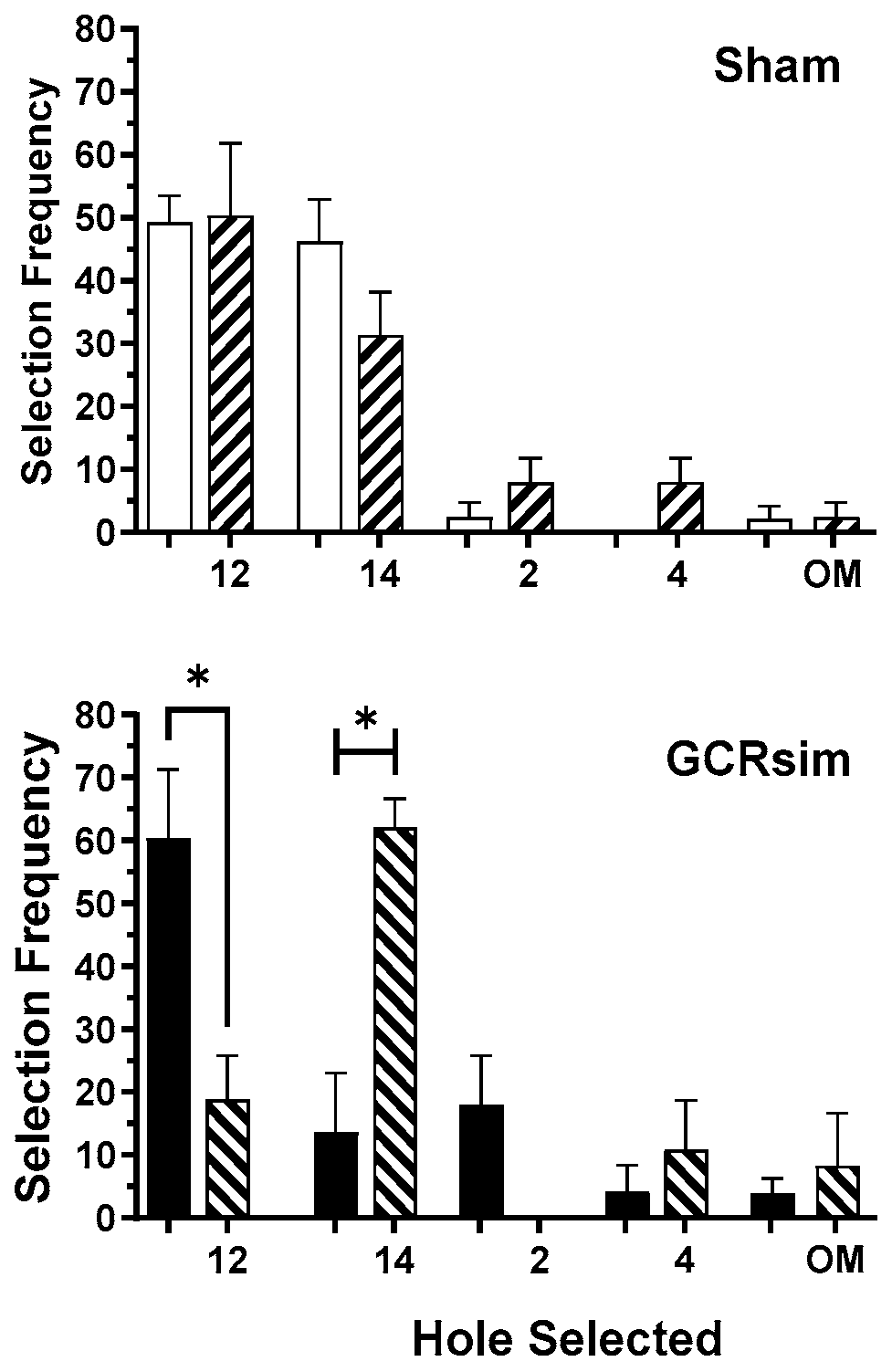

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, S.R.; Jorge, M.; Bell, S.T. Ensuring Safe Decision-Making on the Moon and Mars: Cognitive Performance Assessment for Exploration Class Mission EVA. In Proceedings of the 13th International Association for the Advancement of Space Safety (IAASS) Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 8–10 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Basner, M.; Dinges, D.F.; Mollicone, D.J.; Savelev, I.; Ecker, A.J.; Di Antonio, A.; Jones, C.W.; Hyder, E.C.; Kan, K.; Morukov, B.V.; et al. Psychological and Behavioral Changes during Confinement in a 520-Day Simulated Interplanetary Mission to Mars. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, R.D.; Wilkinson, R.T. The Detection of Sleep Onset: Behavioral and Physiological Convergence. Psychophysiology 1984, 21, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, P.; Taillard, J.; Sagaspe, P.; Valtat, C.; Sanchez-Ortuno, M.; Moore, N.; Charles, A.; Bioulac, B. Age, Performance and Sleep Deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2004, 13, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesensten, N.J.; Killgore, W.D.S.; Balkin, T.J. Performance and Alertness Effects of Caffeine, Dextroamphetamine, and Modafinil during Sleep Deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2005, 14, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, Y.; Lee, A.; Raha, O.; Pillai, K.; Gupta, S.; Sethi, S.; Mukeshimana, F.; Gerard, L.; Moghal, M.U.; Saleh, S.N.; et al. Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Cognitive and Physical Performance in University Students. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2017, 15, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boardman, J.M.; Bei, B.; Mellor, A.; Anderson, C.; Sletten, T.L.; Drummond, S.P.A. The Ability to Self-Monitor Cognitive Performance during 60 h Total Sleep Deprivation and Following 2 Nights Recovery Sleep. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 27, e12633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.L.; Raj, S.; Croft, R.J.; Hayley, A.C.; Downey, L.A.; Kennedy, G.A.; Howard, M.E. Slow Eyelid Closure as a Measure of Driver Drowsiness and Its Relationship to Performance. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2016, 17, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmer, J.S.; Dinges, D.F. Neurocognitive Consequences of Sleep Deprivation. Semin. Neurol. 2005, 25, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, S.; Dinges, D.F. Behavioral and Physiological Consequences of Sleep Restriction. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2007, 3, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Dinges, D.F. Sleep Deprivation and Vigilant Attention. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1129, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Rao, H.; Durmer, J.S.; Dinges, D.F. Neurocognitive Consequences of Sleep Deprivation. Semin. Neurol. 2009, 29, 320–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Dickinson, D.L. Bargaining and Trust: The Effects of 36-h Total Sleep Deprivation on Socially Interactive Decisions. J. Sleep Res. 2010, 19, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J.C.; Chong, P.L.H.; Ganesan, S.; Leong, R.L.F.; Chee, M.W.L. Sleep Deprivation Increases Formation of False Memory. J. Sleep Res. 2016, 25, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, C.M.; Bullmore, E.T.; Henson, R.N.; Christensen, S.; Miller, S.; Smith, M.; Dewit, O.; Lawrence, P.; Nathan, P.J. Effects of Donepezil on Cognitive Performance after Sleep Deprivation. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 26, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, H.; Chylinski, D.O.; Deliens, G.; Leproult, R.; Schmitz, R.; Peigneux, P. Sleep Deprivation Triggers Cognitive Control Impairments in Task-Goal Switching. Sleep 2018, 41, zsx200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliens, G.; Bukowski, H.; Slama, H.; Surtees, A.; Cleeremans, A.; Samson, D.; Peigneux, P. The Impact of Sleep Deprivation on Visual Perspective Taking. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 27, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, W.R.; Ftouni, S.; Drummond, S.P.A.; Maruff, P.; Lockley, S.W.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Anderson, C. The Wake Maintenance Zone Shows Task Dependent Changes in Cognitive Function Following One Night without Sleep. Sleep 2018, 41, zsy148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhardsson, A.; Åkerstedt, T.; Axelsson, J.; Fischer, H.; Lekander, M.; Schwarz, J. Effect of Sleep Deprivation on Emotional Working Memory. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previc, F.H.; Lopez, N.; Ercoline, W.R.; Daluz, C.M.; Workman, A.J.; Evans, R.H.; Dillon, N.A. The Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Flight Performance, Instrument Scanning, and Physiological Arousal in Pilots. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 2009, 19, 326–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, P.; Hinson, J.M.; Jackson, M.L.; Van Dongen, H.P.A. Feedback Blunting: Total Sleep Deprivation Impairs Decision Making That Requires Updating Based on Feedback. Sleep 2015, 38, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, S.; Cheng, I.-C.; Tsai, L.-L. Immediate Error Correction Process Following Sleep Deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2007, 16, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, Y.M.L.; Venkatraman, V.; Dinges, D.F.; Chee, M.W.L. The Neural Basis of Interindividual Variability in Inhibitory Efficiency after Sleep Deprivation. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 7156–7162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Kamimori, G.H.; Balkin, T.J. Caffeine Protects against Increased Risk-Taking Propensity during Severe Sleep Deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2011, 20, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, D. The Cost of Sleep-Related Accidents: A Report for the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research. Sleep 1994, 17, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, B. Impact of Long Work Hours on Police Officers and the Communities They Serve. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2006, 49, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryger, M.H.; Roth, T.; Dement, W.C. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine E-Book: Expert Consult-Online and Print; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; ISBN 1437727735. [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta, F.A.; Alp, M.; Sulzman, F.M.; Wang, M. Space Radiation Risks to the Central Nervous System. Life Sci. Space Res. 2014, 2, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G.A. Space Radiation and Human Exposures, A Primer. Radiat. Res. 2016, 185, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britten, R.A.; Fesshaye, A.; Tidmore, A.; Blackwell, A.A. Similar Loss of Executive Function Performance after Exposure to Low (10 CGy) Doses of Single (4He) Ions and the Multi-Ion GCRSim Beam. Radiat. Res. 2022, 198, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, R.A.; Fesshaye, A.; Tidmore, A.; Liu, A.; Blackwell, A.A. Loss of Cognitive Flexibility Practice Effects in Female Rats Exposed to Simulated Space Radiation. Radiat. Res. 2023, 200, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, S.; Liu, A.; Blackwell, A.A.; Britten, R.A. Multiple Decrements in Switch Task Performance in Female Rats Exposed to Space Radiation. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 449, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, S.; Britten, R. Simulated Space Radiation Exposure Effects on Switch Task Performance in Rats. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2022, 93, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Phuyal, S.; Smits, E.; Reid, F.E.; Tamgue, E.N.; Arriaga, P.A.; Britten, R.A. Exposure to Low (10 cGy) Doses of (4)He Ions Leads to an Apparent Increase in Risk Taking Propensity in Female Rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 474, 115182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, E.; Reid, F.E.; Tamgue, E.N.; Alvarado Arriaga, P.; Nguyen, C.; Britten, R.A. Sex-Dependent Changes in Risk-Taking Predisposition of Rats Following Space Radiation Exposure. Life 2025, 15, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, R.A.; Fesshaye, A.; Ihle, P.; Wheeler, A.; Baulch, J.E.; Limoli, C.L.; Stark, C.E. Dissecting Differential Complex Behavioral Responses to Simulated Space Radiation Exposures. Radiat. Res. 2022, 197, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britten, R.A.; Duncan, V.D.; Fesshaye, A.S.; Wellman, L.L.; Fallgren, C.M.; Sanford, L.D. Sleep Fragmentation Exacerbates Executive Function Impairments Induced by Protracted Low Dose Rate Neutron Exposure. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 97, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, J.S.; Duncan, V.D.; Fesshaye, A.; Tondin, A.; Macadat, E.; Britten, R.A. Exposure to ≤15 Cgy of 600 Mev/n 56 Fe Particles Impairs Rule Acquisition but Not Long-Term Memory in the Attentional Set-Shifting Assay. Radiat. Res. 2018, 190, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burket, J.A.; Matar, M.; Fesshaye, A.; Pickle, J.C.; Britten, R.A. Exposure to Low (≤10 CGy) Doses of 4He Particles Leads to Increased Social Withdrawal and Loss of Executive Function Performance. Radiat. Res. 2021, 196, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, R.A.; Fesshaye, A.S.; Duncan, V.D.; Wellman, L.L.; Sanford, L.D. Sleep Fragmentation Exacerbates Executive Function Impairments Induced by Low Doses of Si Ions. Radiat. Res. 2020, 194, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.V.; Fesshaye, A.S.; Tidmore, A.; Sanford, L.D.; Britten, R.A. Sleep Fragmentation Results in Novel Set-Shifting Decrements in GCR-Exposed Male and Female Rats. Radiat. Res. 2025, 203, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, V.K.; Allen, B.D.; Caressi, C.; Kwok, S.; Chu, E.; Tran, K.K.; Chmielewski, N.N.; Giedzinski, E.; Acharya, M.M.; Britten, R.A.; et al. Cosmic Radiation Exposure and Persistent Cognitive Dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.M.; Decicco-Skinner, K.L.; Roma, P.G.; Hienz, R.D. Individual Differences in Attentional Deficits and Dopaminergic Protein Levels Following Exposure to Proton Radiation. Radiat. Res. 2014, 181, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, M.M.; Baulch, J.E.; Klein, P.M.; Baddour, A.A.D.; Apodaca, L.A.; Kramár, E.A.; Alikhani, L.; Garcia, C.; Angulo, M.C.; Batra, R.S.; et al. New Concerns for Neurocognitive Function during Deep Space Exposures to Chronic, Low Dose-Rate, Neutron Radiation. eNeuro 2019, 6, ENEURO.0094-19.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.K. Casualties as a Measure of the Loss of Combat Effectiveness of an Infantry Battalion; Operations Research Office, Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Oonk, M.; Davis, C.J.; Krueger, J.M.; Wisor, J.P.; Van Dongen, H.P.A. Sleep Deprivation and Time-on-Task Performance Decrement in the Rat Psychomotor Vigilance Task. Sleep 2015, 38, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Córdova, C.A.; Said, B.O.; McCarley, R.W.; Baxter, M.G.; Chiba, A.A.; Strecker, R.E. Sleep Deprivation in Rats Produces Attentional Impairments on a 5-Choice Serial Reaction Time Task. Sleep 2006, 29, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deurveilher, S.; Bush, J.E.; Rusak, B.; Eskes, G.A.; Semba, K. Psychomotor Vigilance Task Performance during and Following Chronic Sleep Restriction in Rats. Sleep 2015, 38, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, R.A.; Jewell, J.S.; Duncan, V.D.; Hadley, M.M.; Macadat, E.; Musto, A.E.; Tessa, C. La Impaired Attentional Set-Shifting Performance after Exposure to 5 CGy of 600 MeV/n 28Si Particles. Radiat. Res. 2018, 189, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, S.M.; Stark, C.E.L. Age-Related Deficits in the Mnemonic Similarity Task for Objects and Scenes. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 333, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaba, T.C.; Blattnig, S.R.; Norbury, J.W.; Rusek, A.; La Tessa, C. Reference Field Specification and Preliminary Beam Selection Strategy for Accelerator-Based GCR Simulation. Life Sci. Space Res. 2016, 8, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreollo, N.A.; dos Santos, E.F.; de Araujo, M.R.; Lopes, L.R. Rat’s Age versus Human’s Age: What Is the Relationship? ABCD Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. = Braz. Arch. Dig. Surg. 2012, 25, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Véras-Silva, A.S.; Mattos, K.C.; Gava, N.S.; Brum, P.C.; Negrão, C.E.; Krieger, E.M. Low-Intensity Exercise Training Decreases Cardiac Output and Hypertension in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1997, 273, H2627–H2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Tessa, C.; Sivertz, M.; Chiang, I.H.; Lowenstein, D.; Rusek, A. Overview of the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory. Life Sci. Space Res. 2016, 11, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, J.G.; Tartar, J.L.; Bebis, A.C.; Ward, C.P.; McKenna, J.T.; Baxter, M.G.; McGaughy, J.; McCarley, R.W.; Strecker, R.E. Experimental Sleep Fragmentation Impairs Attentional Set-Shifting in Rats. Sleep 2007, 30, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.; Zhang, S.X.L.; Ramesh, V.; Hakim, F.; Kaushal, N.; Wang, Y.; Gozal, D. Sleep Fragmentation Induces Cognitive Deficits via Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Oxidase-Dependent Pathways in Mouse. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, V.; Nair, D.; Zhang, S.X.L.; Hakim, F.; Kaushal, N.; Kayali, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.C.; Carreras, A.; Gozal, D. Disrupted Sleep without Sleep Curtailment Induces Sleepiness and Cognitive Dysfunction via the Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Pathway. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessa, P.P. Net Free Statistics and Forecasting Software. Available online: https://www.wessa.net/stat.wasp#cite (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Britten, R.A.; Duncan, V.D.; Fesshaye, A.; Rudobeck, E.; Nelson, G.A.; Vlkolinsky, R. Altered Cognitive Flexibility and Synaptic Plasticity in the Rat Prefrontal Cortex after Exposure to Low (≤15 CGy) Doses of 28Si Radiation. Radiat. Res. 2020, 193, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, R.A.; Fesshaye, A.S.; Tidmore, A.; Tamgue, E.N.; Alvarado-Arriaga, P.A. Different Spectrum of Space Radiation Induced Cognitive Impairments in Radiation-Naïve and Adapted Rats. Life Sci. Space Res. 2024, 43, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, N.D.; Niv, Y.; Dayan, P. Uncertainty-Based Competition between Prefrontal and Dorsolateral Striatal Systems for Behavioral Control. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 1704–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonart, G.; Parris, B.; Johnson, A.M.; Miles, S.; Sanford, L.D.; Singletary, S.J.; Britten, R.A. Executive Function in Rats Is Impaired by Low (20 CGy) Doses of 1 GeV/u 56Fe Particles. Radiat. Res. 2012, 178, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiakis, E.C.; Pinheiro, M.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, H.; Beheshti, A.; Dutta, S.M.; Russell, W.K.; Emmett, M.R.; Britten, R.A. Quantitative Proteomic Analytic Approaches to Identify Metabolic Changes in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex of Rats Exposed to Space Radiation. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 971282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whoolery, C.W.; Yun, S.; Reynolds, R.P.; Lucero, M.J.; Soler, I.; Tran, F.H.; Ito, N.; Redfield, R.L.; Richardson, D.R.; Shih, H.-Y.; et al. Multi-Domain Cognitive Assessment of Male Mice Shows Space Radiation Is Not Harmful to High-Level Cognition and Actually Improves Pattern Separation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.I.; Kangas, B.D.; Luc, O.T.; Solakidou, E.; Smith, E.C.; Dawes, M.H.; Ma, X.; Makriyannis, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Dayeh, M.A.; et al. Complex 33-Beam Simulated Galactic Cosmic Radiation Exposure Impacts Cognitive Function and Prefrontal Cortex Neurotransmitter Networks in Male Mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Sugimoto, C.; Regan, S.L.; Pitzer, E.M.; Fritz, A.L.; Sertorio, M.; Mascia, A.E.; Vatner, R.E.; Perentesis, J.P.; Vorhees, C.V. Cognitive and Behavioral Effects of Whole Brain Conventional or High Dose Rate (FLASH) Proton Irradiation in a Neonatal Sprague Dawley Rat Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.J.; Link, T.D.; Hu, Y.Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, E.H.-J.; Lilascharoen, V.; Aronson, S.; O’Neil, K.; Lim, B.K.; Komiyama, T. Corticostriatal Flow of Action Selection Bias. Neuron 2019, 104, 1126–1140.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.J.; Dahlen, J.E.; Mukundan, M.; Komiyama, T. History-Based Action Selection Bias in Posterior Parietal Cortex. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.D.; Jaramillo, J.; Wang, X.-J. Working Memory and Decision-Making in a Frontoparietal Circuit Model. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 12167–12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Event | Time Relative to SR Exposure | Rat Age |

|---|---|---|

| Arrival at EVMS | ~12 weeks prior | ~3 months |

| Exercise | ~11–3 weeks prior | |

| Shipment to BNL | 1 week prior | |

| SR exposure | - | ~6 months |

| Return to EVMS | 1 week post | |

| Exercise | 1–14 weeks post | |

| ARMIT testing | 14–18 weeks post | ~10 months |

| Stage 1 | Response Window | # Correct Selections | Completion Rate | Permitted # Sessions | Days at Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRT15 | N/A | ≥30 | ≥60% | 8 | 1 |

| SRT4 | N/A | ≥30 | ≥60% | 8 | 1 |

| SRT1-Timed | 30 s | ≥30 | ≥75% | 8 | 2 |

| SRT1-Fast | 10 s | ≥30 | ≥75% | 10 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Britten, R.A.; Tamgue, E.N.; Arriaga Alvarado, P.; Fesshaye, A.S.; Sanford, L.D. A Two-Hit Model of Executive Dysfunction: Simulated Galactic Cosmic Radiation Primes Latent Deficits Revealed by Sleep Fragmentation. Life 2025, 15, 1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111717

Britten RA, Tamgue EN, Arriaga Alvarado P, Fesshaye AS, Sanford LD. A Two-Hit Model of Executive Dysfunction: Simulated Galactic Cosmic Radiation Primes Latent Deficits Revealed by Sleep Fragmentation. Life. 2025; 15(11):1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111717

Chicago/Turabian StyleBritten, Richard A., Ella N. Tamgue, Paola Arriaga Alvarado, Arriyam S. Fesshaye, and Larry D. Sanford. 2025. "A Two-Hit Model of Executive Dysfunction: Simulated Galactic Cosmic Radiation Primes Latent Deficits Revealed by Sleep Fragmentation" Life 15, no. 11: 1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111717

APA StyleBritten, R. A., Tamgue, E. N., Arriaga Alvarado, P., Fesshaye, A. S., & Sanford, L. D. (2025). A Two-Hit Model of Executive Dysfunction: Simulated Galactic Cosmic Radiation Primes Latent Deficits Revealed by Sleep Fragmentation. Life, 15(11), 1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111717