New Insights into the Mucus-Secreting Cells in the Proventriculus of 10 Day Old Ross 308 Broiler Chickens—A Qualitative RGB Color Study by Histochemical Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

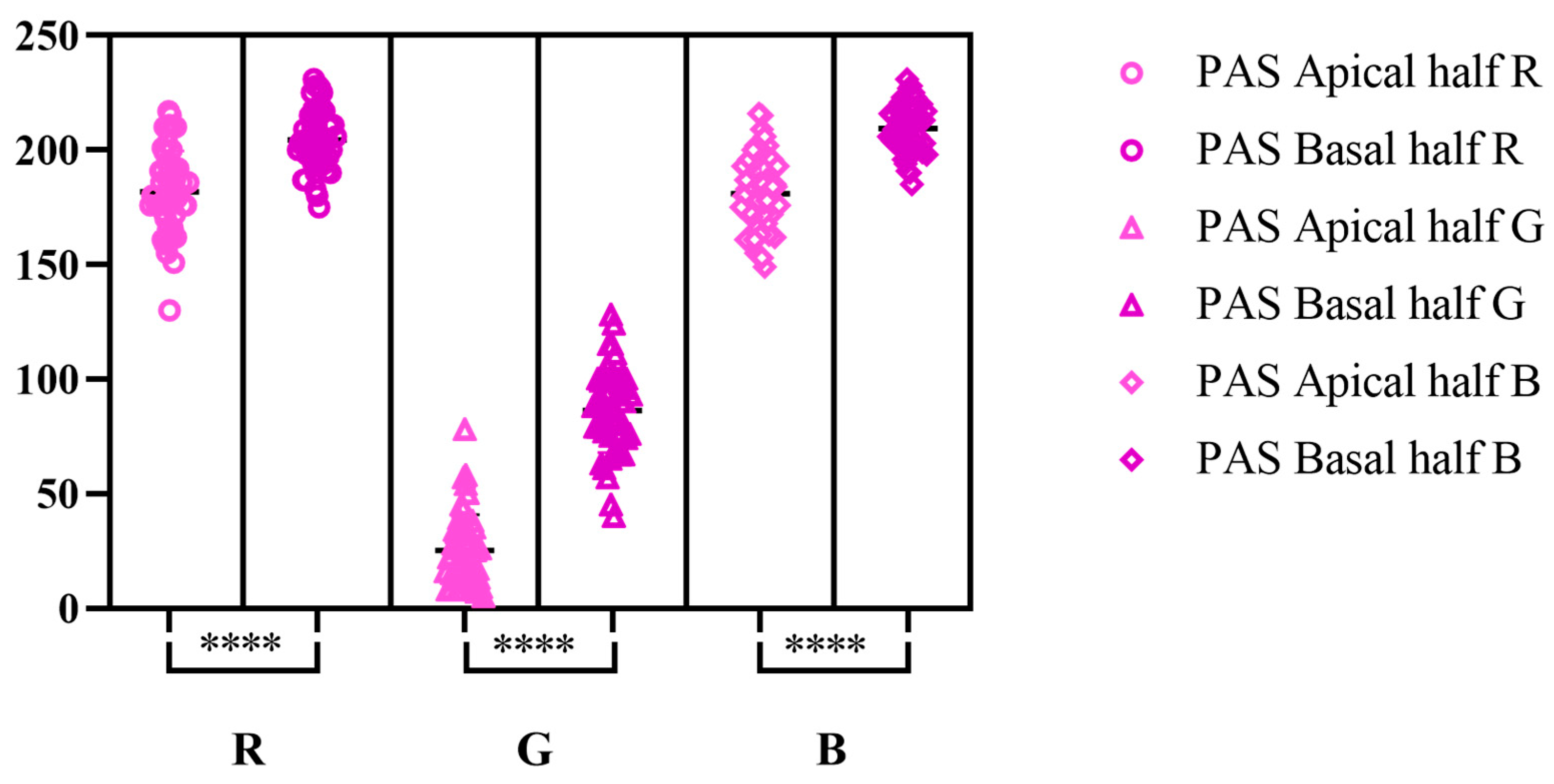

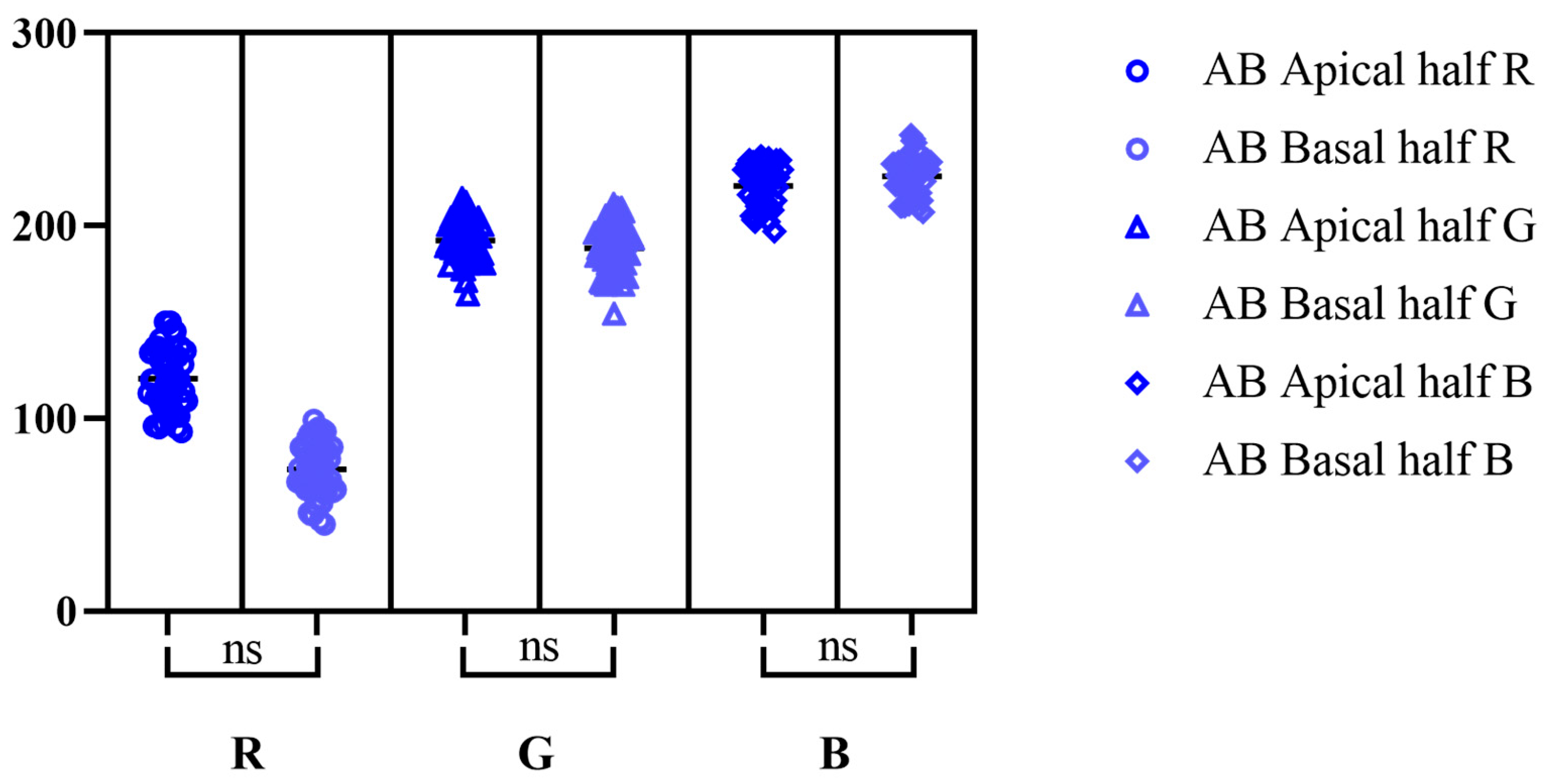

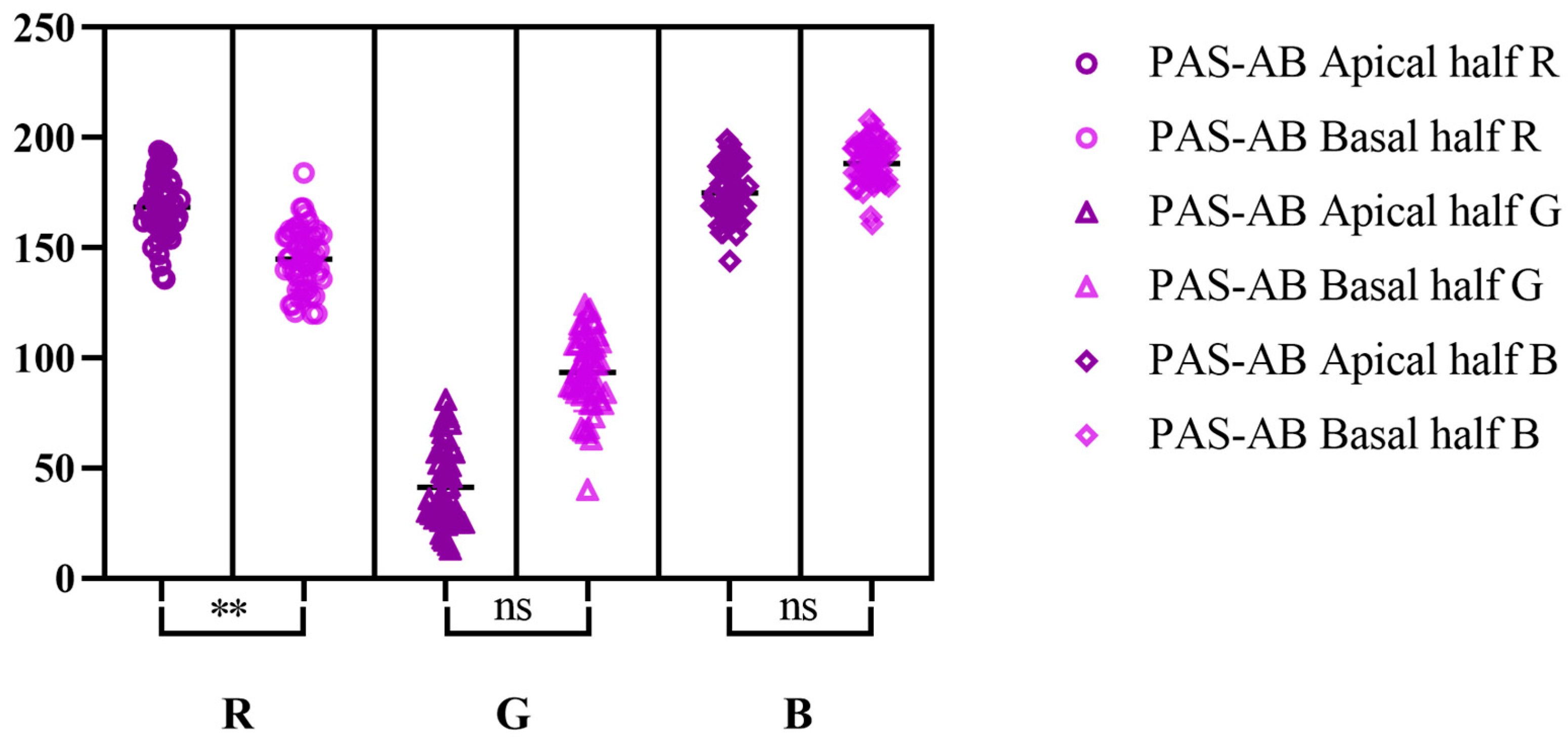

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zuidhof, M.J.; Schneider, B.L.; Carney, V.L.; Korver, D.R.; Robinson, F.E. Growth, efficiency, and yield of commercial broilers from 1957, 1978, and 2005. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2970–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, Y.; Sklan, D. Posthatch development in poultry. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1997, 6, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, V.; Abdollahi, M.R. Nutrition and digestive physiology of the broiler chick: State of the art and outlook. Animals 2021, 11, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D.C.; Oliveira, N.L.; Santos, E.T.; Guzzi, A.; Dourado, L.R.; Ferreira, G.J. Morphological characterization of the gastrointestinal tract of Cobb 500® broilers. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2015, 35, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, H.H.; Zabiba, I.M. Morphohistometrical study for prevntriculus in pre- and post-hatching broiler chicks. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 8315–8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Ridha, A.; Salih, A.N.; Bargooth, A.F.; Wali, O.N. Comparative histological study of stomach in domestic pigeon (Columba livia domestica) and domestic quail (Coturnix coturnix). Biochem. Cell. Arch. 2019, 19, 4241–4245. [Google Scholar]

- Udoumoh, A.F.; Nwaogu, I.C.; Igwebuike, U.M.; Obidike, I.R. Histogenesis and histochemical features of gastric glands of pre-hatch and post-hatch broiler chicken. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2020, 50, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlak, B.H.; Faraj, S.S. Morphohistological study of the proventriculus of Eurasian marsh harrier Circus aeruginosus (Linnaeus, 1766) (Aves, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae). Bull. Iraq Nat. Hist. Mus. 2024, 18, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saran, D.; Meshram, B. Histomorphological and histochemical studies on proventriculus in guinea fowl (Numida meleagris). Indian J. Anim. Res. 2021, 55, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.K.; Bhanja, S.K.; Sunder, G.S. Early post hatch nutrition on immune system development and function in broiler chickens. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2015, 71, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Tako, E.; Ferket, P.R.; Uni, Z. Mucin gene expression and mucin content in the chicken intestinal goblet cells are affected by in ovo feeding of carbohydrates. Poult. Sci. 2006, 85, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varum, F.J.; Basit, A.W. Gastrointestinal mucosa and mucus. In Mucoadhesive Materials and Drug Delivery Systems; Khutoryanskiy, V.V., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L.; Li, Z.J.; Wei, Z.S.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.Z.; Liao, Y.; Luo, Y. Long-term effects of oral tea polyphenols and Lactobacillus brevis M8 on biochemical parameters, digestive enzymes, and cytokines expression in broilers. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2015, 16, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I.; Choct, M. The foregut and its manipulation via feeding practices in the chicken. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3188–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Eicher, S.D.; Applegate, T.J. Development of intestinal mucin 2, IgA, and polymeric Ig receptor expressions in broiler chickens and Pekin ducks. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duangnumsawang, Y.; Zentek, J.; Goodarzi Boroojeni, F. Development and functional properties of intestinal mucus layer in poultry. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 745849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, L.J.; Al-Zubaidi, K.A. Comparison between histometric and histochemical of proventriculus of adult pigeon (Columba livia domestica) and duck (Anas platyrhynchos). Biochem. Cell. Arch. 2021, 21, 2051. [Google Scholar]

- Alsanosy, A.A.; Noreldin, A.E.; Elewa, Y.H.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Elnasharty, M.A.; Aboelnour, A. Comparative features of the upper alimentary tract in the domestic fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus) and kestrel (Falco tinnunculus): A morphological, histochemical, and scanning electron microscopic study. Microsc. Microanal. 2021, 27, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Maksoud, M.K.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Nabil, T.M.; Moawad, U.K. Histomorphological, histochemical and scanning electron microscopic investigation of the proventriculus (ventriculus glandularis) of the hooded crow (Corvus cornix). Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2022, 51, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacranie, A.; Adiya, X.; Mydland, L.T.; Svihus, B. Effect of intermittent feeding and oat hulls to improve phytase efficacy and digestive function in broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2017, 58, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moquet, P.C. Butyrate in Broiler Diets: Impact of Butyrate Presence in Distinct Gastrointestinal Tract Segments on Digestive Function, Microbiota Composition and Immune Responses; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Golberg, M.; Kobos, J.; Clarke, E.; Bajaka, A.; Smędra, A.; Balawender, K.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Seneczko, M.; Orkisz, S.; Żytkowski, A. Application of histochemical stains in anatomical research: A brief overview of the methods. Transl. Res. Anat. 2024, 30, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Y.; Altamirano, E.; Ortega, V.; Paz, P.; Valdivié, M. Effect of age on the immune and visceral organ weights and cecal traits in modern broilers. Animals 2021, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Poel, A.V.; Abdollahi, M.R.; Cheng, H.; Colovic, R.; Den Hartog, L.A.; Miladinovic, D.; Page, G.; Sijssens, K.; Smillie, J.F.; Thomas, M.; et al. Future directions of animal feed technology research to meet the challenges of a changing world. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 270, 114692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, S.K.; Layton, C.; Bancroft, J.D. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 7th ed.; Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier: London, UK, 2013; pp. 224–226. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Yin, X.; Huo, X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, J. Development of a colorimetric sensor array with weighted RGB strategy for quality differentiation of Anji white tea. J. Food Eng. 2025, 391, 112458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, M.; Nunobiki, O.; Taniguchi, E.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kakudo, K. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of stain color using RGB computer color specification. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 1999, 21, 477–480. [Google Scholar]

- AbdElnaeem, A.; Elshaer, F.; Rady, M. Histological and histochemical studies of the esophagus and stomach in two types of birds with different feeding behaviors. Int. J. Dev. 2019, 8, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, I.A.; Ali, A.A.; Ahmed, S.G.; Al-Samawy, E.R.; Fj, A.S. Histology and histochemical structure of the stomach (proventriculus and ventriculus) in moorhen (Gallinula chloropus) in South Iraq. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbağ, E.; Çınar, K.; Tabur, M.; Aştı, R. Histochemical structure of stomach (proventriculus and gizzard) in some bird species. Süleyman Demirel Univ. J. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2015, 19, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sasan, J.S.; Suri, S.; Sarma, K. Histomorphometrical and histochemical studies on the glandular stomach (proventriculus) of Poonchi bird of Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Agric. Assoc. Text. Chem. Crit. Rev. 2023, 11, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Zaher, M.; El-Ghareeb, A.W.; Hamdi, H.; AbuAmod, F. Anatomical, histological and histochemical adaptations of the avian alimentary canal to their food habits: I-Coturnix coturnix. Life Sci. J. 2012, 9, 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Abdellatif, A.M.; Farag, A.; Metwally, E. Anatomical, histochemical, and immunohistochemical observations on the gastrointestinal tract of Gallinula chloropus (Aves: Rallidae). BMC Zool. 2022, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariyadi, B.; Sri Harimurti, S.H. Effect of indigenous probiotics lactic acid bacteria on the small intestinal histology structure and the expression of mucins in the ileum of broiler chickens. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2015, 14, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Sklan, D.; Uni, Z. Mucin dynamics in the chick small intestine are altered by starvation. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PAS | AB pH-2.5 | PAS-AB | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apical Half | Basal Half | Apical Half | Basal Half | Apical Half | Basal Half | |||||||||||||

| R | G | B | R | G | B | R | G | B | R | G | B | R | G | B | R | G | B | |

| Min | 130 | 5 | 149 | 175 | 40 | 185 | 93 | 164 | 197 | 45 | 154 | 207 | 136 | 13 | 144 | 120 | 40 | 161 |

| Max | 217 | 78 | 216 | 231 | 128 | 231 | 150 | 214 | 236 | 99 | 211 | 247 | 194 | 81 | 199 | 184 | 124 | 208 |

| M | 181.7 | 25.22 | 181 | 204.6 | 86.44 | 209.4 | 120.7 | 192.3 | 220.5 | 73.5 | 188.4 | 225.5 | 168.5 | 41.32 | 175 | 145 | 93.54 | 188.3 |

| SD | 17.87 | 15.71 | 16.04 | 13.15 | 18.39 | 10.26 | 16.38 | 10.75 | 10.56 | 14.07 | 12.64 | 10.06 | 13.92 | 17.8 | 12.35 | 14.07 | 17.53 | 9.863 |

| SEM | 2.527 | 2.221 | 2.268 | 1.86 | 2.6 | 1.451 | 2.316 | 1.521 | 1.493 | 1.989 | 1.787 | 1.422 | 1.969 | 2.517 | 1.746 | 1.99 | 2.479 | 1.395 |

| CV% | 9.831 | 62.28 | 8.860 | 6.429 | 21.27 | 4.901 | 13.57 | 5.592 | 4.787 | 19.14 | 6.706 | 4.458 | 8.264 | 43.07 | 7.057 | 9.708 | 18.74 | 5.237 |

| L 95% CI | 176.7 | 20.76 | 176.5 | 200.8 | 81.21 | 206.5 | 116.0 | 189.2 | 217.5 | 69.50 | 184.8 | 222.7 | 164.5 | 36.26 | 171.5 | 141.0 | 88.56 | 185.5 |

| U 95% CI | 186.8 | 29.68 | 185.6 | 208.3 | 91.67 | 212.3 | 125.4 | 195.4 | 223.5 | 77.50 | 192.0 | 228.4 | 172.5 | 46.38 | 178.5 | 149.0 | 98.52 | 191.1 |

| The Most Intense (Darkest) Color from the Average (Min Value) | Average Color Value | The Least Intense (Lightest) Color from the Average (Max Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAS reaction | |||

| The apical half of the glands in the mucosa |  |  |  |

| The basal half of the glands in the mucosa |  |  |  |

| AB pH-2.5 staining | |||

| The apical half of the glands in the mucosa |  |  |  |

| The basal half of the glands in the mucosa |  |  |  |

| PAS-AB staining | |||

| The apical half of the glands in the mucosa |  |  |  |

| The basal half of the glands in the mucosa |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rus, V.; Matei-Lațiu, M.-C.; Gal, A.F. New Insights into the Mucus-Secreting Cells in the Proventriculus of 10 Day Old Ross 308 Broiler Chickens—A Qualitative RGB Color Study by Histochemical Assessment. Life 2025, 15, 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111716

Rus V, Matei-Lațiu M-C, Gal AF. New Insights into the Mucus-Secreting Cells in the Proventriculus of 10 Day Old Ross 308 Broiler Chickens—A Qualitative RGB Color Study by Histochemical Assessment. Life. 2025; 15(11):1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111716

Chicago/Turabian StyleRus, Vasile, Maria-Cătălina Matei-Lațiu, and Adrian Florin Gal. 2025. "New Insights into the Mucus-Secreting Cells in the Proventriculus of 10 Day Old Ross 308 Broiler Chickens—A Qualitative RGB Color Study by Histochemical Assessment" Life 15, no. 11: 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111716

APA StyleRus, V., Matei-Lațiu, M.-C., & Gal, A. F. (2025). New Insights into the Mucus-Secreting Cells in the Proventriculus of 10 Day Old Ross 308 Broiler Chickens—A Qualitative RGB Color Study by Histochemical Assessment. Life, 15(11), 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111716