A Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Interventions to Reduce Binge Drinking

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- What types of psychological interventions have been evaluated through RCTs for the treatment of BD?

- −

- How effective are these interventions in reducing the frequency and intensity of BD episodes?

- −

- To what extent do participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as age and gender, influence the effectiveness of psychological interventions?

- −

- What other associated effects (physical, psychological, or social) have been reported as outcomes of psychological interventions for the treatment of BD?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria (Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria)

2.3. Data Extraction and Assessment of Risk of Bias

3. Results

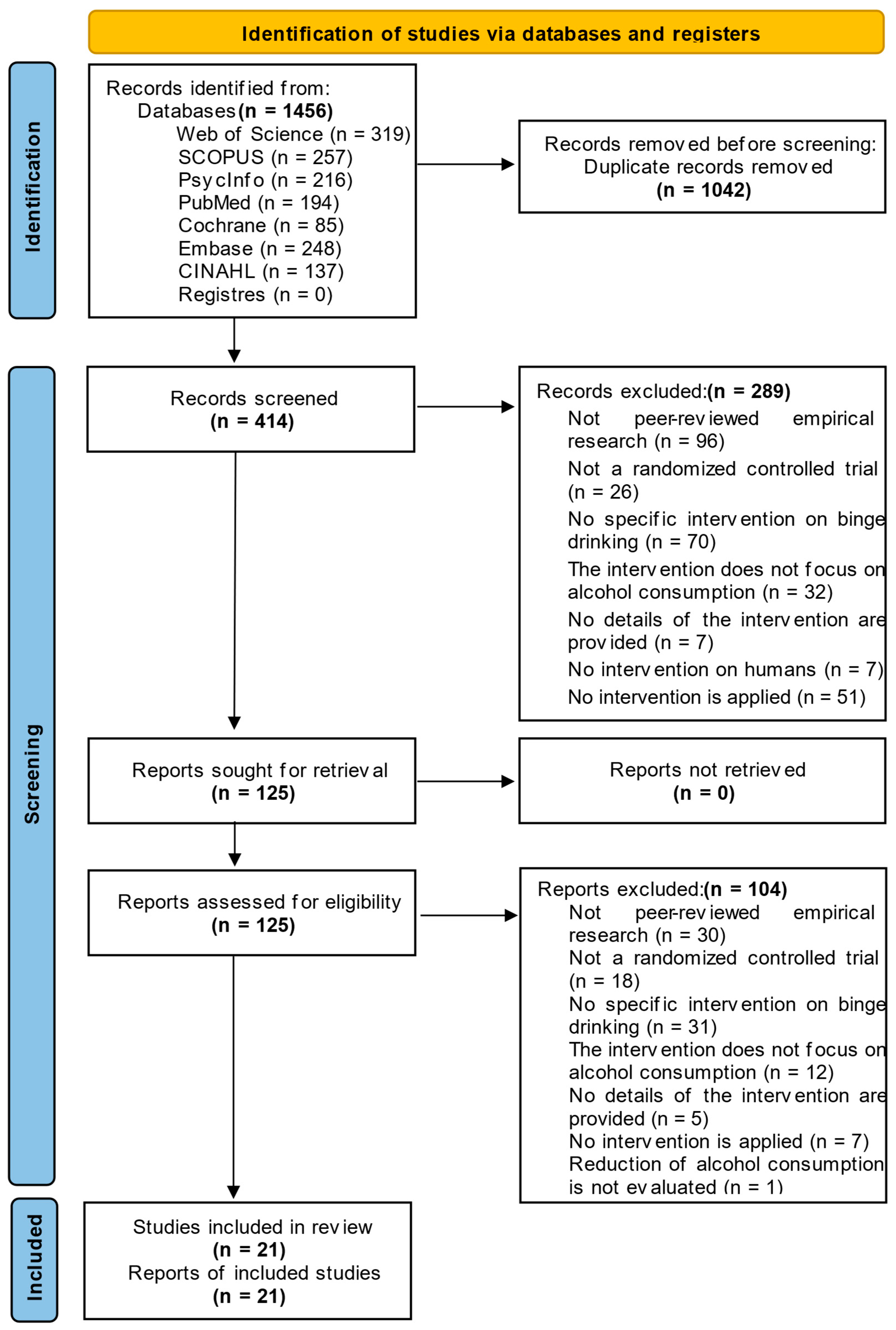

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Descriptive Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias

3.4. Characteristics of Interventions

3.4.1. Format for Applying Interventions and Type of Interventions

3.4.2. Total Number of Sessions and Duration

3.4.3. Post-Intervention Follow-Up

3.4.4. Application of Previously Designed Programs

3.4.5. Incentives Offered to Participants

3.4.6. Theoretical Basis of the Interventions

3.5. Effectiveness of Interventions in BD

3.5.1. On the Prevalence of BD

3.5.2. On the Frequency of BD Episodes

3.5.3. About the Amount of Alcohol Consumed in Each BD Episode

3.5.4. Other Psychosocial and Consumption-Related Variables

4. Discussion

- Overview of Evidence and Intervention Effectiveness

- Cultural and Contextual Determinants of Intervention Outcomes

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author(s) (Year) (Country) | Sample and Sociodemographic Characteristics 2 | Theoretical Framework of the Intervention | Characteristics of the Intervention 1 | Results 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voogt et al. [32] (The Netherlands) | N = 609 (nIG = 318; nCG = 291); 59.9% male; Age M = 17.3 (SD = 1.3) | Motivational perspective; principles of Motivational Interviewing; elements of the I- Change Model | Program: What Do You Drink (WDYD); Modality: digital, individual; Sessions: 4 (1: LB; 2: intervention; 3–4: follow- up); Duration: not explicitly specified (see Voogt et al. [33]; Follow-up: 1 and 6 months; Incentives: none | Reduction in BD: Not s.d. at one (%IG 25.3; %CG 26.3; OR = 0.96; 95%CI [0.84, 1.10]; p = 0.54) and six months (%IG 29.5; %CG 31.5; OR = 0.97; 95% CI [0.84, 1.11]; p = 0.65) follow-up. BD frequency: Not significantly different at one (%IG 43.3; %CG 47.7; OR = 0.92; 95% CI [0.82, 1.04]; p = 0.18) and six months (%IG 55.3; %CG 57.5; OR = 0.95; 95% CI [0.85, 1.06]; p = 0.35) follow-up. BD intensity: Not evaluated |

| Jander et al. [37] (The Netherlands) | N = 2649 (nIG = 1622; nCG = 1027); 52.7% male; Age M = 16.35 (SD = 1.2) | I-Change model | Program: Alcohol Alert (“What happened?!”); modality: digital, individual (web game with personalized feedback); sessions: 6 (1: LB; 2–4: game with feedback; 5: assessment and comparison of alcohol consumption with Danish pattern; 6: follow-up); Duration: not specified; follow-up: 4 months; incentives: raffle of 300 vouchers worth €25 | Reduction in BD: Not specified (OR = 0.48; 95% CI [0.18, 1.25]; p = 4.13). In the 15-year-old subgroup, significant effect on IG (OR = 0.47; 95% CI [0.24, 0.91]; p = 0.03) at 4 months. BD frequency: If parents participated, young people had fewer BD episodes (p = 0.04). BD intensity: Not evaluated |

| White & Pohl [41] (Germany) | N = 43 (nIG = 22; nCG = 19); 34.9% male; Age M = 21.6 (SD = 2.2) | Cognitive–behavioral motivational approach | Program: Attention bias paradigm; modality: digital, individual, self- administered (web); sessions: 7 (1: LB; 2–6: intervention; 7: follow-up); intervention: 6 sessions (2 per week during 3 weeks); duration: not specified; follow-up: 1 month after intervention; incentives: $50 voucher or academic credit | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Not s.d. (Fl,35 = 0.58; p = 0.451). BD intensity: Not evaluated. Secondary outcomes: increased negative expectations related to alcohol |

| Vargas-Martínez et al. [39] (Spain) | N = 1247 (nIG = 742; nCG = 505); 46.99% male; Age M = 16.78 (SD = 1.06) | I-Change model | Program: Alcohol Alert with personalized feedback; modality: digital, individual according to the protocol of Jander et al. [37]; sessions: 6 (1: LB; 2–3: OH scenarios; 4: challenge not to consume/booster session; 5: change assessment; 6: follow-up); duration: not specified; follow-up: at 4 months; incentives: none | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: No significant reduction (p not reported). Positive regression coefficient between adherence and fewer episodes of BD (b = −0.104; p < 0.1). BD intensity: Not evaluated. Secondary outcomes: increased perception of quality of life |

| Arden & Armitage [31] (United Kingdom) | N = 56 (nIG = 21; nCG = 35); 33.9% male; Age M = 20.51 (SD = 1.9) | The transtheoretical model [49] | Program: not specified; modality: in- person, individual, single, brief, self- administered; tool: Volitional Help Sheet; sessions: 2 (1: intervention; 2: follow-up); duration: not specified; follow-up: 2 weeks; incentives: none | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Significant effect of the intervention (F2,52 = 4.11; p = 0.02). Effect size: η2 = 0.14 (moderate). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant reduction in episodes between IG and CG (p = 0.01), and between IG and Active CG (p = 0.03). BD intensity: Not evaluated |

| Murgraff et al. [27] (United Kingdom) | N = 102 (nIG = 54; nCG = 48); 26.5% male; Age M = 26.38 (SD = 9.66) | Social Cognition Theory; Implementation Intentions Model [54]; Self-Regulation and Planning Model [53] | Program: not specified; modality: face-to-face, group; sessions: 2 (1: intervention-planning implementation intention procedure; 2: follow-up); duration: not specified; follow-up: 2 weeks; incentives: none | Reduction in BD: IG significant reduction in the proportion of participants in BD (χ2 = 5.32, df = 1; p = 0.05). BD frequency: IG significant reduction in BD frequency (F1,96 = 8.98; p < 0.01). BD intensity: Not evaluated |

| Hedman & Akagi [29] (USA) | N = 131 (nIG = 68; nCG = 63); 58.0% male; Age M = 19.45 (SD = 1.22) | Elaboration Likelihood Model [56] | Program: not specified; modality: digital, individual (emails with personalized feedback); sessions: 14 (1: LB; 2–13: email intervention –12 emails in 6 weeks–; 14: follow-up); duration: not specified; follow-up: at 1.5 months (email); incentives: none | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Significant decrease in IG in frequency of 3+ BD episodes (z = −2.45; p = 0.01). BD intensity: not significant decrease in average number of drinks per BD episode. Secondary outcomes: Decrease in risk behaviors and attitudes toward consumption. |

| Hanewinkel et al. [26] (Germany) | N = 4163 (nIG = 2124; nCG = 2039); 52.1% male; Age M = 15.61 (SD = 0.73) | Motivational perspective | Program: Klar bleiben (Stay clear- headed) school program; modality: in- person, group; sessions: 20 (1: pre- intervention; 2–19: biweekly intervention for 9 weeks; 20: post- intervention); duration: not specified; follow-up: 6 months; incentives: participation in raffles | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Not significant one month after intervention (OR = 0.95; 95% CI [0.69, 1.30]; p = 0.73). BD intensity: Not significant at one month after the intervention (OR = −0.03; 95% CI [−0.29, 0.23]; p = 0.84). Secondary outcomes: No significant effects on overall alcohol consumption, social factors, alcohol- related cognition, or other substance use |

| Carey et al. [11] (USA) | N = 484 (nIG = 256; nCG = 227); 55.72% male; Age M = 18.7 (SD = 0.8) | Self-Affirmation Theory [55] | Program: e-CheckUpToGo; modality: digital, individual; sessions: 7 (1: LB; 2: intervention; 3–7: follow-up); duration = 1.5 h; follow-up: 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months; incentives: a) reduction in punishment, b) Amazon gift cards ($150) | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Significant decrease at six months (b = −0.77; p < 0.001). No long-term (6–12 months) s.d. (b = 0.06; p < 0.58). BD intensity: Not evaluated. Secondary outcomes: increased perception of negative consequences and improved self- perception. |

| Voogt et al. [33] (The Netherlands) | N = 907 (nIG = 456; nCG = 451); 60.2% male; Age M = 20.49 (SD = 1.7) | Motivational perspective; Principles of motivational interviewing; Elements of the I-Change model | Program: What Do You Drink (WDYD); modality: digital, individual; sessions: 4 (1: LB; 2: intervention per month; 3– 4: follow-up); duration: intervention = 20 min, others not specified; follow- up: at 1 and 6 months; incentives: €100 for completing final assessment | Reduction in BD: Not significantly different at one month (OR = 0.92; 95% CI [0.64, 1.31]; p = 0.63] or at six months (OR = 1.10; 95% CI [0.83, 1.46]; p = 0.52). BD frequency: Not significantly different at one month (OR = 0.88; 95% CI [0.61, 1.25]; p = 0.46) or at 6 months (OR = 1.09; 95% CI [0.82, 1.44]; p = 0.56) BD intensity: Not evaluated |

| Wood et al. [28] (USA) | N = 335 (nIG = 84; nCG not indicated); 47.5% men; Age M = 20.9 (SD = 0.91) | Motivational perspective [47]; AEC, expectations of change regarding alcohol [78] | Program: Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI) and Expectancy of Change Intervention (AEC); modality: BMI = face-to-face, individual; AEC = group; sessions: BMI = 1 session (45– 60 min); CEE = 2 sessions (1: LB; 2: follow-up); follow-up: 1, 3, and 6 months; incentives: $100 for evaluations and raffle for 3 prizes ($100 each) | Reduction in BD: Significant decrease [BMI (β = −0.23; p < 0.05); AEC (β = −0.28; p < 0.01)]. Only AEC was significantly positively associated with the Quadratic factor of Excessive Alcohol Consumption, indicating a significant decline in the intervention. BD frequency: Not evaluated. BD intensity: Not evaluated. |

| Daeppen et al. [30] (Switzerland) | N = 418 (nIG = 199; nCG = 219); 100% male; Age M = 19.9 (SD = 1.0) | Motivational perspective, BMI [51,52] | Program: Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI); modality: in person, individual; sessions: 3 (1: pre-intervention; 2: intervention at 9 weeks; 3: follow-up); duration: intervention = 15.8 min (±5.5); follow- up: at 6 months; incentives: none | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Significant difference in monthly episodes of BD (IRR = 0.81; 95% CI [0.67, 0.97]; p = 0.04). BD intensity: Not evaluated. Secondary outcomes: lower intention to change and less substance use. |

| Martínez-Montilla et al. [40] (Spain) | N = 1247 (nIG = 742; nCG = 505); 46.99% male; Age M = 16.31 (SD = 1.06) | I-Change model | Program: Alcohol Alert; modality: digital, individual, with personalized feedback; sessions: 6 (1: LB + intervention; 2–3: OH scenarios; 4: challenge not to consume alcohol excessively at the next event; 5: evaluation of the challenge; 6: follow- up); duration: 1 h per session; interval: 1–2 weeks (adapted to school schedule); follow-up: at 4 months; incentives: none | Reduction in BD: Significant reduction in IG (OR = 0.72; 95% CI [0.55, 0.94]; p = 0.02), n.s. in CG (OR = 0.82; 95% CI [0.60, 1.126]; p = 0.22). The probability of BD episodes in the CG was nine times higher than in the IG (OR = 9.13; 95% CI [1.11, 75.26]; p = 0.04). BD frequency: Not evaluated. BD intensity: Not evaluated. |

| Williams et al. [36] (USA) | N = 281 (nIG and nCG not specified); 17% men; Age M = 38.5 (SD = not reported) | Ecological Development Theory [58,59,60] | Program: Families: Preparing the New Generation (FPNG); modality: in-person, group; sessions: 10 (1: LB; 2– 9: intervention; 10: follow-up); duration: unspecified; follow-up: at 12 months; incentives: $30 | Reduction in BD: Significant reduction in the Parents + Youth group (OR = 0.29; p = 0.007). Not significant in the Youth Only group and in the CG (OR = 0.84; p = 0.64). BD frequency: Not evaluated. BD intensity: Not evaluated |

| Gilmore & Bountress [38] (USA) | N = 264 (nIG = 105; nCG = 159); 0% male; Age M = 18.77 (SD = 0.76) | Motivational, cognitive- behavioral, social influence, transtheoretical, and relapse prevention approaches | Program: BASICS (digital version); modality: digital, individual; protocol by [44], content adapted from Dimeff et al. [43]; sessions: 3 (1: assessment; 2: intervention; 3: follow-up); duration: not specified; follow-up: at 3 months; incentives: course credits (initial assessment) and $25 gift card (follow-up) | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: No s.d. in any of the three intervention groups. CG vs. IG alcohol only (β = −0.073; R2 = 0.005); CG vs. IG sexual assault only (β = −0.005; R2 = 0.000); CG vs. IG alcohol and sexual assault combination (β = −0.045; R2 = 0.002). BD intensity: Not evaluated. Secondary results: higher negative expectations related to alcohol. |

| Voss et al. [42] (USA) | N = 45 (nIG = 24; nCG = 21); 26.63% male; Age M = 18.9 (SD = 1.0) | Behavioral Economics (BE) approach. The role of the time delay value of reinforcement [57] | Program: A-EFT intervention; modality: digital, individual; sessions: 3 (1: LB 65–75 min; 2: A-EFT/VMT task 30 min; 3: follow-up 30 min); includes mobile messaging; follow-up: at 1 month; incentives: $25 (session 1), $25 (follow-up), and $50 gift card raffle | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Not s.d. (F2,37 = 0.28; db = 0.14; SE = 0.33; p = 0.59) both conditions reduced the number of episodes similarly. BD intensity: Not evaluated. Secondary outcomes: greater perception of negative consequences, lower reward effect, and more protective strategies. |

| Witkiewitz et al. [34] (USA) | N = 94 (nIG = 65; nCG = 29); 72.3% male; Age M = 20.5 (SD = 1.7) | Motivational, cognitive- behavioral, social influence, transtheoretical, and relapse prevention approaches | Program: BASICS-Mobile; modality: digital, individual (text messages + momentary ecological assessment); sessions: 4 (1: LB 40–45 min; 2–3: intervention via EMA; 4: follow-up); follow-up: at 1 month; incentives: $20 (LB), $3/random assessment + $21/week for adherence (up to $168), $30 (follow-up) | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Not s.d. at 1- month follow-up (χ2 = 0.09; gl = 2, 76; p = 0.91). BD intensity: Not assessed. Secondary outcomes: reduced perception of negative consequences. |

| Voogt et al. [35] (Netherlands) | N = 456 (nIG = 456; nCG = 451); 60.3% men; Age M = 20.85 (SD = 1.7) | Motivational perspective; Principles of Motivational Interviewing (MI); Elements of the I- Change model | Program: What Do You Drink (WDYD); modality: digital, individual plus momentary ecological assessment (EMA); sessions: 5 (1: LB 40 min; 2: intervention 20 min; 3–5: follow-up 260 min total: 26 post-tests × 10 min); additional: 4 pre-tests × 10 min; follow-up: weekly for 6 months (30 measurements, 250 min analyzed); incentives: €100 upon completion of ≥28/30 surveys | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Significant decrease at 1 month (b = −1.15; p = 0.01), 3 months (b = −0.12; p = 0.01), and 6 months (b = −0.09; p = 0.045). BD intensity: Not evaluated. |

| Conrod et al. [22] (United Kingdom) | N = 368 (nIG = 199; nCG = 169); 40.97% male; Age M = 14 (SD = not reported) | Theoretical approach focused on Motivational Interviewing; Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy; Personality | Program: not specified; modality: face-to-face, group; content: real-life scenarios of young people with high-risk personality traits; sessions: 5 (1: LB; 2–3: group intervention 90 min/session; 4–5: follow-up); follow-up: at 6 and 12 months; no incentives | Reduction in BD: Significant reduction in the probability of BD in the IG at 6 months (OR = 0.41; p = 0.009) and at 12 months (OR = 0.50; p = 0.016). BD frequency: Not evaluated. BD intensity: Not evaluated. |

| Crombie et al. [15] (United Kingdom) | N = 825 (nIG = 411; nCG = 414); 100% men; Age M = 34.6 (SD = not reported) | HAPA (Health Action Process Approach) model: motivational phase (intention, risk perception, self- efficacy) and volitional phase (planning, relapse prevention) | Program: not specified; modality: digital, individual via SMS; intervention: 12 weeks, up to 4 messages/day, total 112 messages; sessions: not specified; follow-up: 2 sessions (3 and 12 months); no incentives | Reduction in BD: Not specified (OR = 0.77; 95% CI [0.55, 1.09]; p = 0.143). BD frequency: Not reported (Bayesian factor does not reach the threshold of 3.0 for moderate evidence in favor of the experimental hypothesis). BD intensity: Not evaluated |

| Chavez & Palfai [21] (USA) Study 1 | N = 30 (nIG = 16; nCG = 14); 30% men; Age M = 18.87 (SD = 1.17) | Cognitive- motivational processes related to alcohol: perceived norms, protective strategies, readiness to change, and self- regulation | Program: eCHECKUP TO GO-Alcohol; modality: digital, individual (mobile app plus email); sessions: 3 (1: LB; 2: intervention; 3: follow-up); duration: 4 weeks; follow-up: 1 session (1 month); no incentives (participants in an academic course) | Reduction in BD: Not evaluated. BD frequency: Regression analysis indicated that the WEB + TEXT intervention resulted in a medium to large effect size (f2 = 0.26) on the reduction in episodes of excessive alcohol consumption (β = −0.38, p < 0.05). BD intensity: Not evaluated. Secondary results: greater self-efficacy, more social norms, fewer perceived negative consequences, greater intention to change, fewer behavioral protection strategies |

References

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2025 NSDUH: Alcohol Facts and Statistics [Internet]; NIAAA: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data on Excessive Alcohol Use. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/excessive-drinking-data/index.html (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Chung, T.; Creswell, K.G.; Bachrach, R.; Clark, D.B.; Martin, C.S. Adolescent binge drinking: Developmental context and opportunities for prevention. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2018, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, M.T.; Motos, P. Cómo definir y medir el Consumo Intensivo de Alcohol. In Consumo Intensivo de Alcohol en Jóvenes. Guía Clinica; Cortés, M.T., Ed.; Socidrogalcohol: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche, E.; Kuntsche, S.; Thrul, J.; Gmel, G. Binge drinking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 976–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESPAD Group. Key Findings from the 2024 European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD); European Union Drugs Agency: Lisbon, Portugal, 2025; Available online: https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/data-factsheets/espad-2024-key-findings_en (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Bonsu, L.; Kumra, P.; Awan, A.; Sharma, M. A systematic review of binge drinking interventions and bias assessment among college students and young adults in high-income countries. Camb. Prism. Glob. Ment. Health 2024, 11, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Montes, M.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Paz-Zulueta, M.; Sarabia-Cobo, C.; Ruiz-Azcona, L.; Parás-Bravo, P. Binge Drinking in Spanish University Students: Associated Factors and Repercussions: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Sebena, R.; Warich, J.; Naydenova, V.; Dudziak, U.; Orosova, O. Alcohol Drinking in University Students Matters for Their Self-Rated Health Status: A Cross-sectional Study in Three European Countries. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingson, R.W.; Zha, W.; White, A.M. Drinking beyond the binge threshold: Predictors, consequences, and changes in the US. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, K.B.; DiBello, A.M.; Magill, M.; Mastroleo, N.R. Does self-affirmation augment the effects of a mandated personalized feedback intervention? A randomized controlled trial with heavy drinking college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2024, 38, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, P.F.P.; Valente, J.Y.; Rezende, L.F.M.; Sanchez, Z.M. Binge drinking in Brazilian adolescents: Results of a national household survey. Cad. Saude Publica 2022, 38, e00077322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, M.N.S.; Eleotério, A.E.; Oliveira, F.D.A.; Pedroni, L.C.B.D.R.; Lacena, E.E. Prevalence and factors associated with binge drinking among Brazilian young adults, 18 to 24 years old. Braz. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 23, e200092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Ngin, C.; Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Health and behavioral factors associated with binge drinking among university students in nine ASEAN countries. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2017, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, I.K.; Irvine, L.; Williams, B.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Petrie, D.; Jones, C.; Norrie, J.; Evans, J.M.M.; Emslie, C.; Rice, P.M.; et al. Texting to Reduce Alcohol Misuse (TRAM): Main findings from a randomized controlled trial of a text message intervention to reduce binge drinking among disadvantaged men. Addiction 2018, 113, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-López, L.M.; Cárdenas, S.J. Ansiedad social consumo riesgoso de alcohol en adolescentes mexicanos. J. Behav. Health Soc. Issues 2014, 6, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumas, D.M.; Workman, C.; Smith, D.; Navarro, A. Reducing high-risk drinking in mandated college students: Evaluation of two personalized normative feedback interventions. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2011, 40, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauduy, M.; Maurage, P.; Mauny, N.; Pitel, A.-L.; Beaunieux, H.; Mange, J. Predictors of alcohol use disorder risk in young adults: Direct and indirect psychological paths through binge drinking. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.E.; Azar, B. High-Intensity Drinking. Alcohol. Res. 2018, 39, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tavolacci, M.P.; Boerg, E.; Richard, L.; Meyrignac, G.; Dechelotte, P.; Ladner, J. Does binge drinking between the age of 18 and 25 years predict alcohol dependence in adulthood? A retrospective case–control study in France. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, K.; Palfai, T.P. Reducing Heavy Episodic Drinking among College Students Using a Combined Web and Interactive Text Messaging Intervention. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 2020, 39, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrod, P.J.; Castellanos, N.; Mackie, C. Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008, 49, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, V.W.; Bour, L.J.; Carter, K.; Chipman, J.J.; Everett, C.C.; Heussen, N.; Hewitt, C.; Hilgers, R.-D.; Luo, Y.A.; Renteria, J.; et al. A roadmap to using randomization in clinical trials. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanewinkel, R.; Tomczyk, S.; Goecke, M.; Isensee, B. Preventing Binge Drinking in Adolescents. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Murgraff, V.; White, D.; Phillips, K. Moderating binge drinking: It is possible to change behaviour if you plan it in advance. Alcohol Alcohol. 1996, 31, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wood, M.D.; Capone, C.; Laforge, R.; Erickson, D.J.; Brand, N.H. Brief motivational intervention and alcohol expectancy challenge with heavy drinking college students: A randomized factorial study. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 2509–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, A.S.; Akagi, C. Effects of an online binge drinking intervention for college students. Am. J. Health Stud. 2008, 23, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Daeppen, J.B.; Bertholet, N.; Gaume, J.; Fortini, C.; Faouzi, M.; Gmel, G. Efficacy of brief motivational intervention in reducing binge drinking in young men: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 113, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arden, M.A.; Armitage, C.J. A volitional help sheet to reduce binge drinking in students: A randomized exploratory trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012, 47, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, C.V.; Kleinjan, M.; Poelen, E.A.; Lemmers, L.A.; Engels, R.C. The effectiveness of a web-based brief alcohol intervention in reducing heavy drinking among adolescents aged 15–20 years with a low educational background: A two-arm parallel group cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, C.V.; Poelen, E.A.; Kleinjan, M.; Lemmers, L.A.; Engels, R.C. The Effectiveness of the ‘What Do You Drink’ Web-based Brief Alcohol Intervention in Reducing Heavy Drinking among Students: A Two-arm Parallel Group Randomized Controlled Trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013, 48, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkiewitz, K.; Desai, S.A.; Bowen, S.; Leigh, B.C.; Kirouac, M.; Larimer, M.E. Development and evaluation of a mobile intervention for heavy drinking and smoking among college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, C.V.; Poelen, E.A.; Kleinjan, M.; Lemmers, L.A.; Engels, R.C. The development of a web-based brief alcohol intervention in reducing heavy drinking among college students: An Intervention Mapping approach. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.R.; Marsiglia, F.F.; Baldwin, A.; Ayers, S. Unintended Effects of an Intervention Supporting Mexican-Heritage Youth: Decreased Parent Heavy Drinking. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2015, 25, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jander, A.; Crutzen, R.; Mercken, L.; Candel, M.; de Vries, H. Effects of a Web-Based Computer-Tailored Game to Reduce Binge Drinking Among Dutch Adolescents: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore, A.K.; Bountress, K.E. Reducing drinking to cope among heavy episodic drinking college women: Secondary outcomes of a web-based combined alcohol use and sexual assault risk reduction intervention. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Martínez, A.M.; Trapero-Bertran, M.; Lima-Serrano, M.; Anokye, N.; Pokhrel, S.; Mora, T. Measuring the effects on quality of life and alcohol consumption of a program to reduce binge drinking in Spanish adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 205, 107597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Montilla, J.M.; Mercken, L.; de Vries, H.; Candel, M.; Lima-Rodríguez, J.S.; Lima-Serrano, M. A Web-Based, Computer-Tailored Intervention to Reduce Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking Among Spanish Adolescents: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J.; Pohl, E.S. Web-delivered multisession alcohol-linked attentional bias modification for binge drinking: Cognitive and behavioral effects in young adult college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2022, 36, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, A.T.; Jorgensen, M.K.; Murphy, J.G. Episodic future thinking as a brief alcohol intervention for heavy drinking college students: A pilot feasibility study. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 30, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimeff, L.A.; Baer, J.S.; Kivlahan, D.R.; Marlatt, G. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A Harm Reduction Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors, C.; Lewis, M.A.; Atkins, D.C.; Jensen, M.M.; Walter, T.; Fossos, N.; Lee, C.M.; Larimer, M.E. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, C.; Kuntsche, E.; Kleinjan, M.; Poelen, E.; Engels, R. Using ecological momentary assessment to test the effectiveness of a web-based brief alcohol intervention over time among heavy-drinking students: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- San Diego State Research Foundation. Alcohol eCHECKUP TO GO for Universities and Colleges. 2021. Available online: https://echeckuptogo.com/programs/alcohol (accessed on 19 June 2025).[Green Version]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of selfchange of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, J.S.; Kivlahan, D.R.; Blume, A.W.; McKnight, P.; Marlatt, G.A. Brief intervention for heavy-drinking college students: 4-year follow-up and natural history. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollnick, S.; Heather, N.; Bell, A. Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: The development of brief motivational interviewing. J. Ment. Health 1992, 1, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviours: Theoretical approaches and a new model. Self-Effic. Thought Control Action. 1992, 217, 242. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer, P.M. Goal achievement: The role of intentions. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 4, 141–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 21, 261–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches; W.C. Brown: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, W.K.; Johnson, M.W.; Koffarnus, M.N.; MacKillop, J.; Murphy, J.G. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 641–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coatsworth, J.D.; Pantin, H.; McBride, C.; Briones, E.; Kurtines, W.; Szapocznik, J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2002, 6, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantin, H.; Schwartz, S.J.; Sullivan, S.; Prado, G.; Szapocznik, J. Ecodevelopmental HIV prevention programs for Hispanic adolescents. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2004, 74, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szapocznik, J.; Coatsworth, J.D. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In Drug Abuse: Origins and Interventions; Glantz, M., Hartel, C.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Risser, M.D. A meta-analysis of brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: Variability in effects across alcohol measures. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2016, 42, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Steinberg, L. Risk-taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lac, A.; Donaldson, C.D. Alcohol attitudes, motives, norms, and personality traits longitudinally classify nondrinkers, moderate drinkers, and binge drinkers using discriminant function analysis. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthenien, A.M.; Lembo, J.; Neighbors, C. Drinking motives and alcohol outcome expectancies as mediators of the association between negative urgency and alcohol consumption. Addict. Behav. 2017, 66, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magid, V.; MacLean, M.G.; Colder, C.R. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 2046–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.P.; Schumann, G.; Rehm, J.; Kornhuber, J.; Lenz, B. Self-management with alcohol over lifespan: Psychological mechanisms, neurobiological underpinnings, and risk assessment. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Lewis, M.A.; Atkins, D.C.; Neighbors, C.; Zheng, C.; Kenney, S.R.; Napper, L.E.; Walter, T.; Kilmer, J.R.; Hummer, J.F.; et al. RCT of web-based personalized normative feedback for college drinking prevention: Are typical student norms good enough? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guckel, T.; Prior, K.; Newton, N.C.; Baillie, A.J.; Teesson, M.; Stapinski, L.A. Psychological mechanisms of change in reducing co-occurring social anxiety and alcohol use: A causal mediation analysis of the online Inroads intervention. Behav. Res. Ther. 2025, 191, 104766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Preventing Harmful Alcohol Use, OECD Health Policy Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.; Manthey, J.; Neufeld, M.; Ferreira-Borges, C.; Olsen, A.; Shield, K.; Rehm, J. Classifying national drinking patterns in Europe between 2000 and 2019: A clustering approach using comparable exposure data. Addiction 2024, 119, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, C.; Ralphs, R.; Stevenson, J.; Smith, A.; Harrison, J.; Kiss, Z.; Armitage, H. The effectiveness of abstinence-based and harm reduction-based interventions in reducing problematic substance use in adults who are experiencing homelessness in high income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2024, 20, e1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.J.; Mallett, K.A.; Turrisi, R.; Sell, N.M.; Reavy, R.; Trager, B. Using latent transition analysis to compare effects of residency status on alcohol-related consequences during the first two years of college. Addict. Behav. 2018, 87, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Boca, F.K.; Darkes, J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: State of the science and challenges for research. Addiction 2003, 98 (Suppl. S2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowin, J.L.; Manza, P.; Ramchandani, V.A.; Volkow, N.D. Neuropsychosocial markers of binge drinking in young adults. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4931–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antón-Toro, L.F.; Shpakivska-Bilan, D.; Del Cerro-León, A.; Bruña, R.; Uceta, M.; García-Moreno, L.M.; Maestú, F. Longitudinal change of inhibitory control functional connectivity associated with the development of heavy alcohol drinking. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1069990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Blázquez-Ornat, I.R.; Gómez-Torres, P.; García-Moyano, L.; Benito-Ruiz, E. Factors related to risky alcohol consumption and binge drinking in Spanish college students: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e089825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkes, J.; Goldman, M.S. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: Experimental evidence for a mediational process. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1993, 61, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murgraff et al. [27] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Wood et al. [28] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Hedman & Akagi [29] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Conrod et al. [22] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Daeppen et al. [30] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Arden & Armitage [31] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Voogt et al. [32] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Voogt et al. [33] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Witkiewitz et al. [34] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Voogt et al. [35] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Williams et al. [36] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Jander et al. [37] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Gilmore & Bountress [38] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Hanewinkel et al. [26] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Crombie et al. [15] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Vargas-Martínez et al. [39] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Martínez-Montilla et al. [40] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Chavez & Palfai [21] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| White & Pohl [41] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Voss et al. [42] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Carey et al. [11] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

: low risk;

: low risk;  : some concerns;

: some concerns;  : high risk;

: high risk;  : no information.

: no information.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giménez-Costa, J.-A.; Martín-del-Río, B.; Gómez-Íñiguez, C.; García-Selva, A.; Motos-Sellés, P.; Cortés-Tomás, M.-T. A Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Interventions to Reduce Binge Drinking. Life 2025, 15, 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111709

Giménez-Costa J-A, Martín-del-Río B, Gómez-Íñiguez C, García-Selva A, Motos-Sellés P, Cortés-Tomás M-T. A Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Interventions to Reduce Binge Drinking. Life. 2025; 15(11):1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111709

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiménez-Costa, José-Antonio, Beatriz Martín-del-Río, Consolación Gómez-Íñiguez, Adrián García-Selva, Patricia Motos-Sellés, and María-Teresa Cortés-Tomás. 2025. "A Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Interventions to Reduce Binge Drinking" Life 15, no. 11: 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111709

APA StyleGiménez-Costa, J.-A., Martín-del-Río, B., Gómez-Íñiguez, C., García-Selva, A., Motos-Sellés, P., & Cortés-Tomás, M.-T. (2025). A Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Interventions to Reduce Binge Drinking. Life, 15(11), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111709