Supplementation of Trimethylamine N-Oxide or Betaine in Semen Improves Quality of Boar Spermatozoa Stored at 17 °C Following Hydrostatic Pressure Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Experimental Animals and Sources

2.3. Experimental Designs

2.4. Semen Collection and Dilution

2.5. Methods

2.5.1. Assessment of Sperm Kinematic Parameters

2.5.2. Assessment of Sperm Viability

2.5.3. Assessment of Sperm MMP

2.5.4. Assessment of Sperm DFI

2.5.5. Assessment of Sperm Plasma Membrane Integrity

2.5.6. Assessment of Sperm Acrosome Integrity

2.5.7. Assessment of ROS Levels in Boar Sperm

2.5.8. Assessment of T-AOC Activity, NO Content, and MDA Concentration in Boar Sperm

2.5.9. Untargeted Lipidomics Analysis

Sample Preparation

Quality Control

LC-MS Analysis

- (1)

- Chromatographic Separation: Samples were separated using an Accucore C30 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 2.6 μm; Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). Mobile phase A consisted of 50% acetonitrile in water containing 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium acetate, and mobile phase B consisted of acetonitrile/isopropanol/water (10:88:2, v/v/v) containing 0.02% formic acid and 2 mM ammonium acetate. The injection volume was 5 μL, and the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. The gradient program was as follows:

- •

- 0–4 min: A decreased from 65% to 40%, B increased from 35% to 60%;

- •

- 4–12 min: A decreased from 40% to 15%, B increased from 60% to 85%;

- •

- 12–15 min: A decreased from 15% to 0%, B increased from 85% to 100%;

- •

- 15–17 min: A held at 0%, B held at 100%;

- •

- 17–18 min: A increased from 0% to 65%, B decreased from 100% to 35%;

- •

- 18–20 min: A held at 65%, B held at 35%.

- (2)

- Mass Spectrometry Detection: Samples were analyzed using electrospray ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative ion modes. The MS parameters were as follows: scanning range, 200–2000 m/z; sheath gas flow, 60 psi; auxiliary gas flow, 20 psi; ion source temperature, 370 °C; ionization voltage, +3000 V (positive mode) and −3000 V (negative mode); collision energy, 20–40–60%.

Detection of Diacylglycerol (DG), Phosphatidylcholine (PC), Sphingomyelin (SM), Ceramide (Cer), and Acylcarnitine (AcCa) Concentrations in Boar Sperm

Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Experiment I

3.1.1. Hydrostatic Pressure Measurement of the Novel Biomimetic Insemination Device

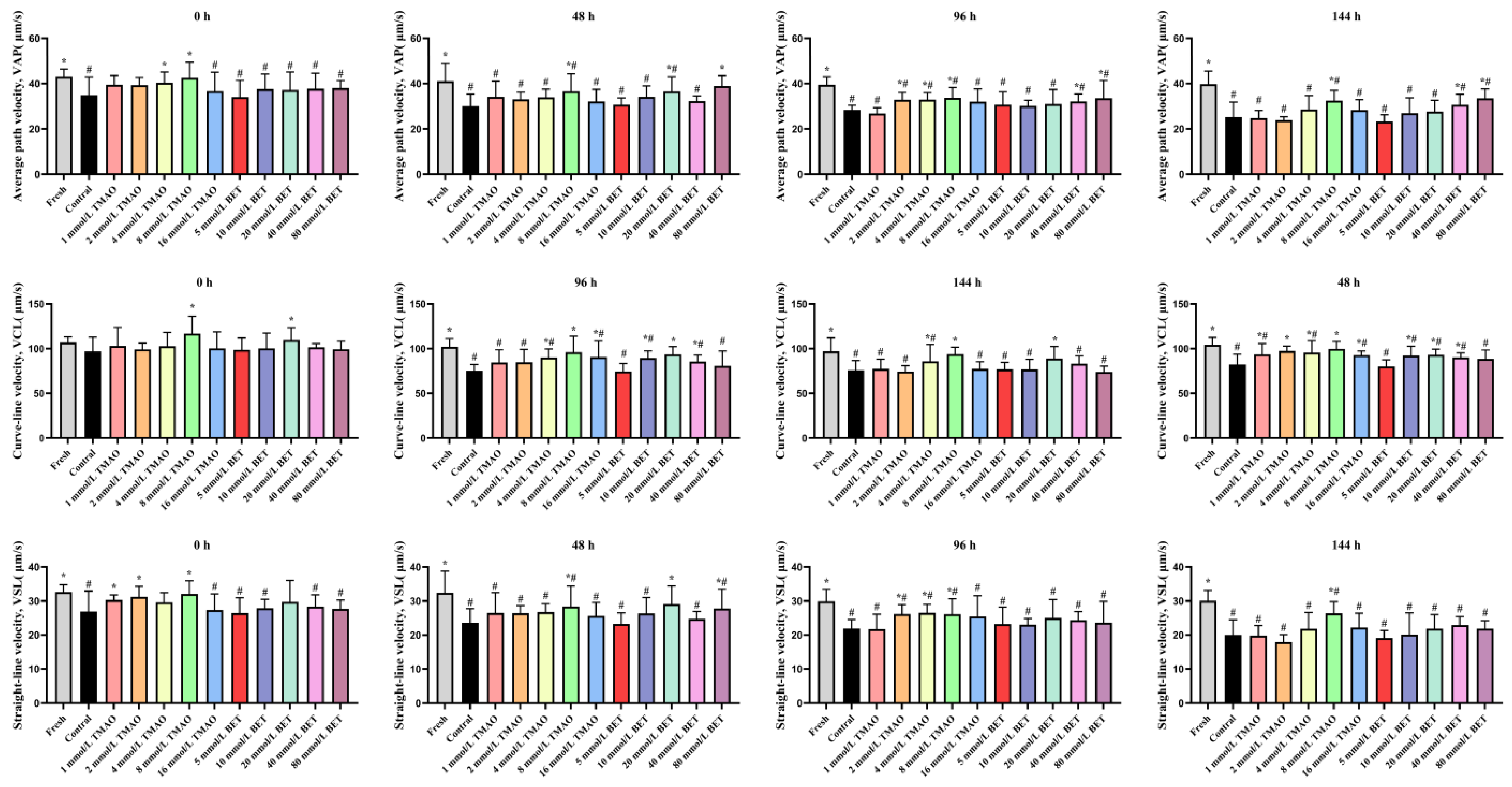

3.1.2. Effects of TMAO or BET on Kinematic Parameters of Boar Sperm Under HP Stress During Room-Temperature Storage

3.2. Experiment II: Effects of TMAO or BET on the Antioxidative Capacity of Boar Semen Under HP Stress

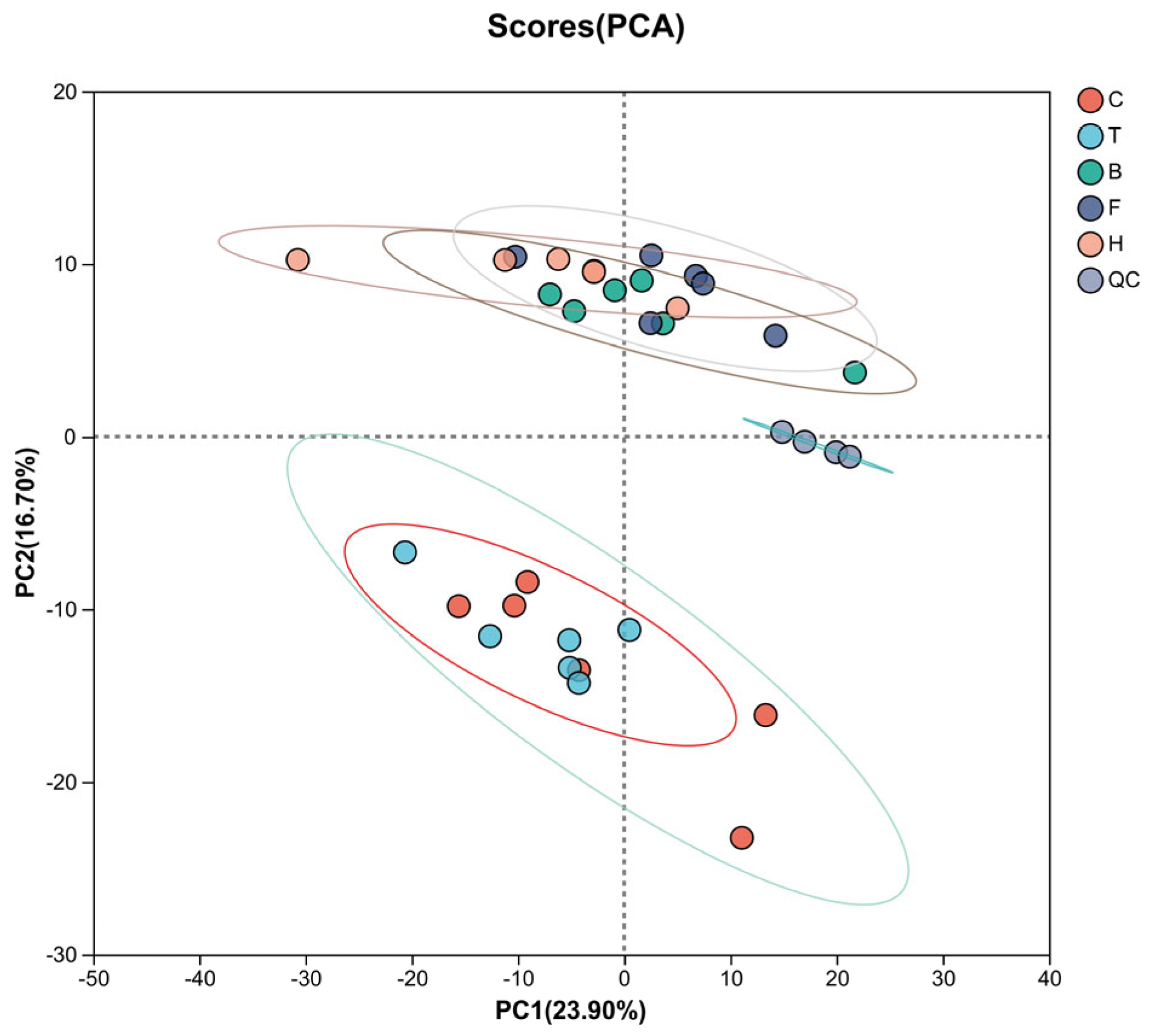

3.3. Experiment III: Effects of TMAO or BET on the Lipid Profile of Boar Sperm During Room-Temperature Storage

3.3.1. PCA

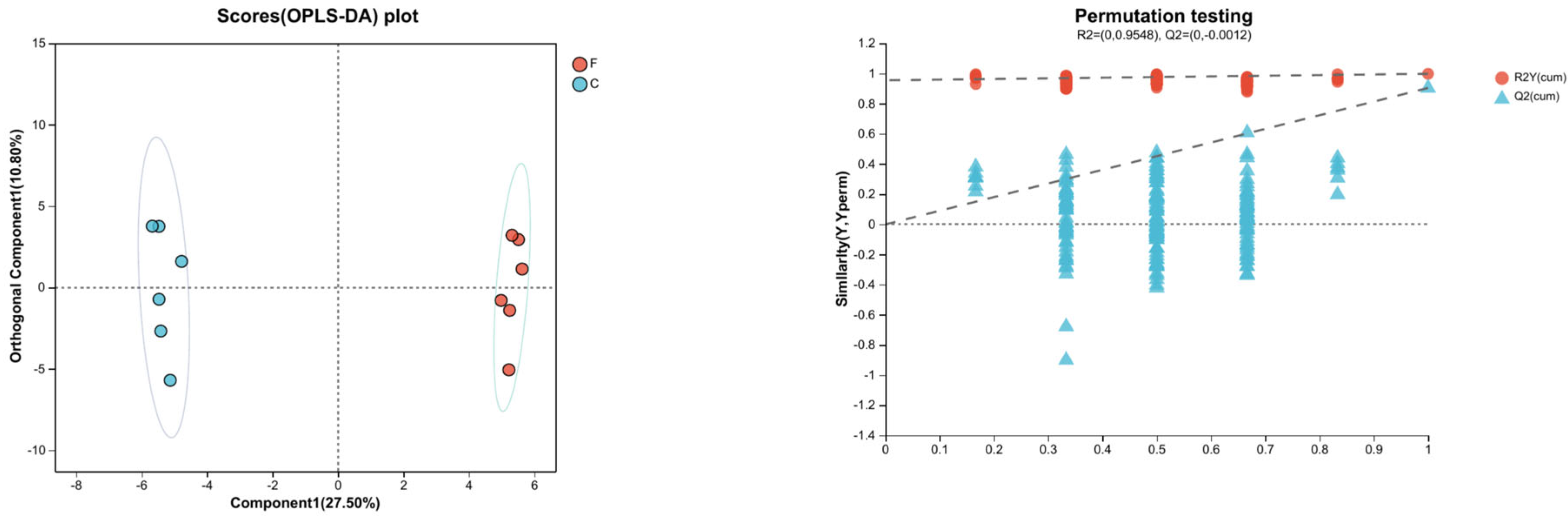

3.3.2. OPLS-DA Analysis

3.3.3. Differential Lipid VIP Analysis

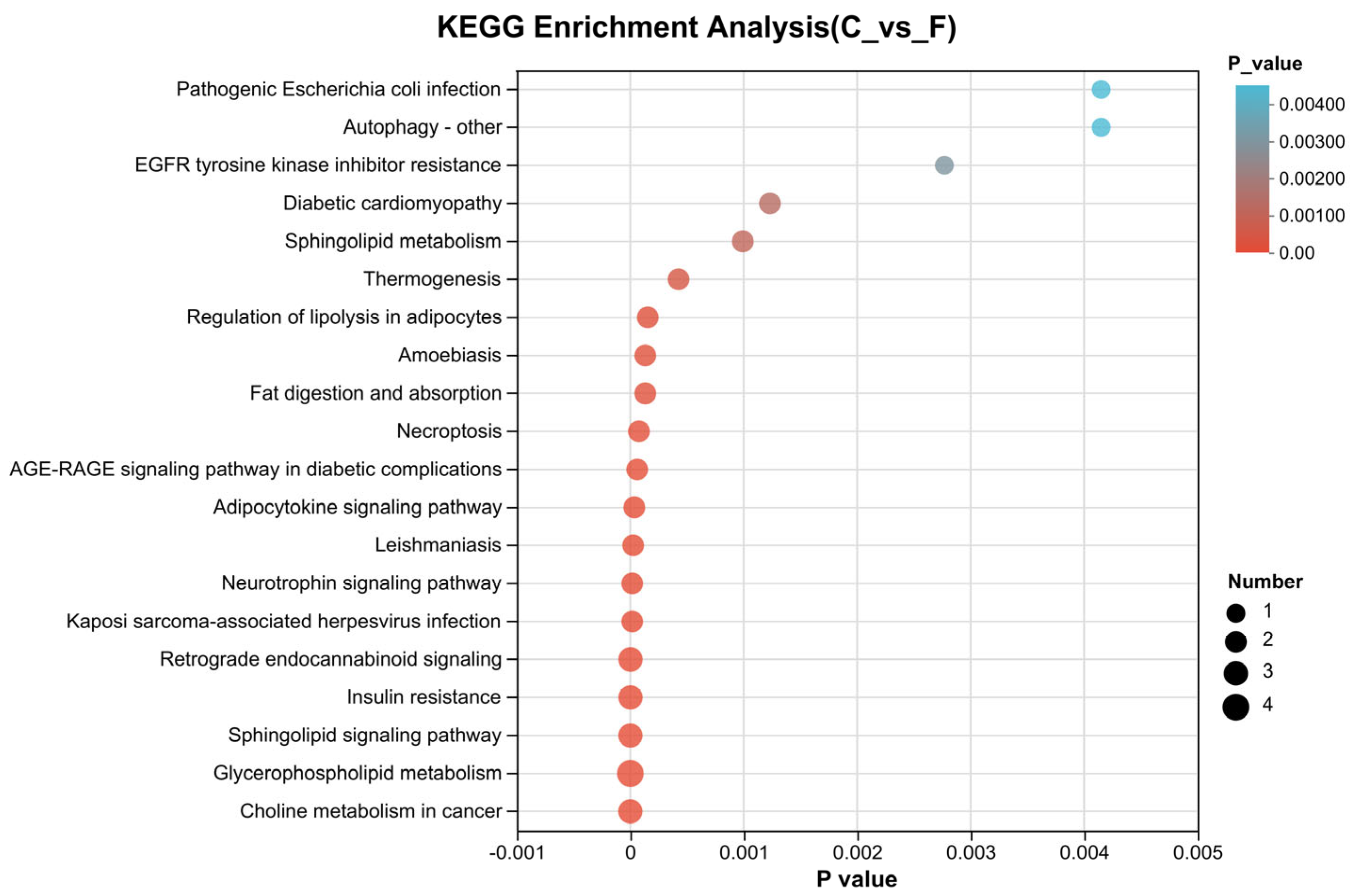

3.3.4. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

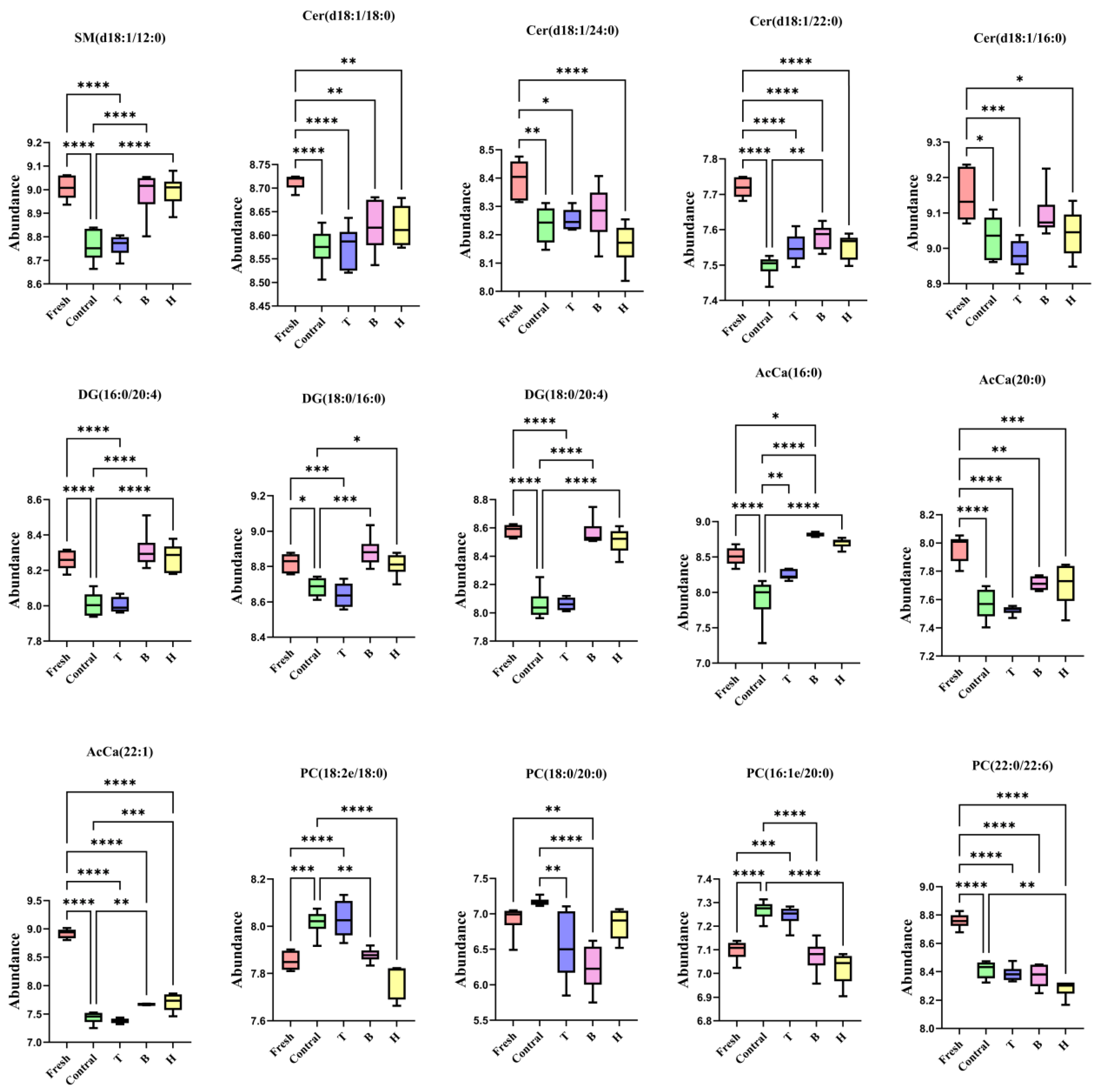

3.3.5. Screening of Differential Lipid Molecules and Signaling Pathways

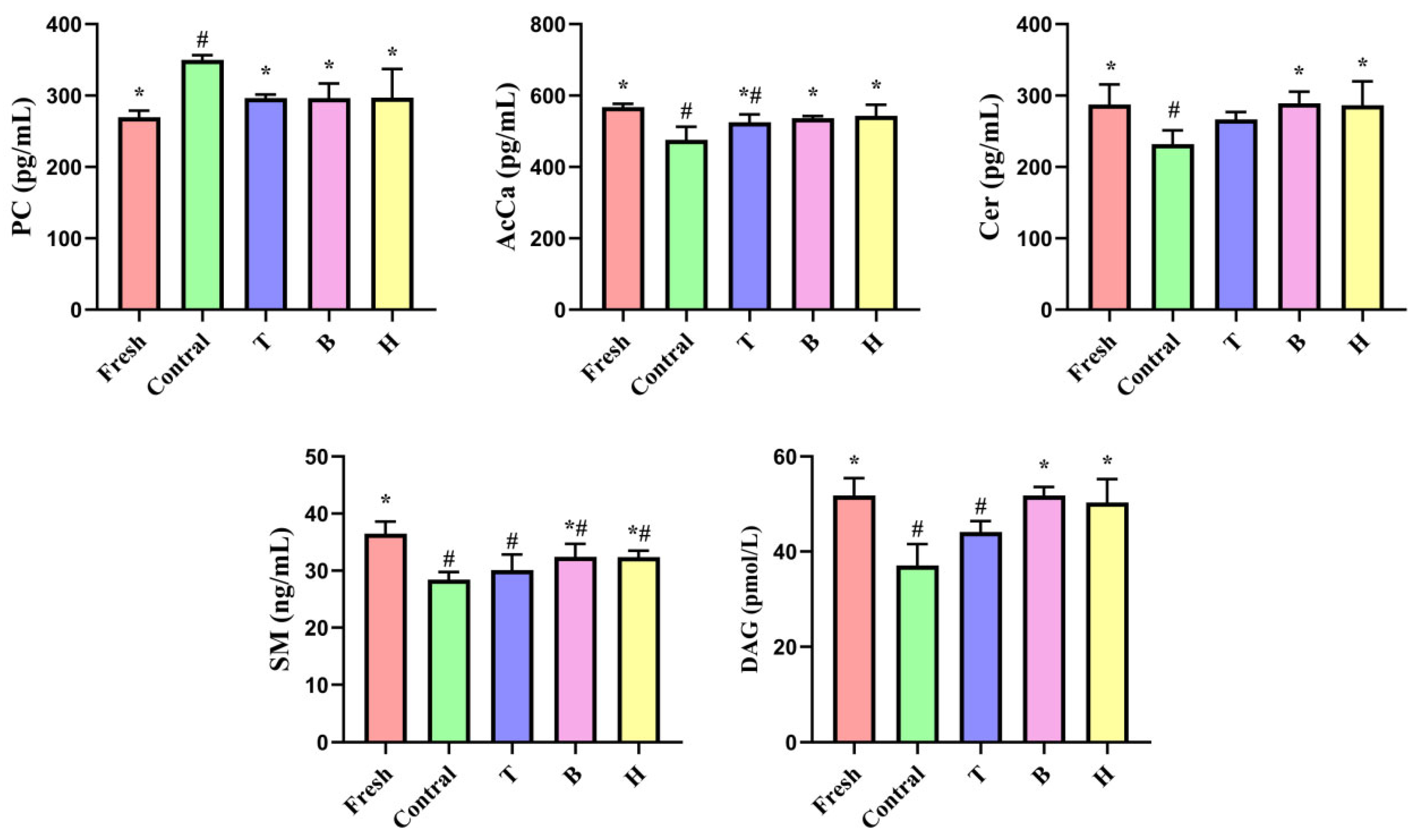

3.3.6. Effects of TMAO or BET on DG, PC, SM, Cer, and AcCa Levels in Boar Sperm

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| BET | Betaine |

| HP | Hydrostatic pressure |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TM | Total motility |

| VCL | Curvilinear velocity |

| VAP | Average path velocity |

| VSL | Straight-line velocity |

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| DFI | DNA fragmentation index |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| T-AOC | Total antioxidative capacity |

| OD | Optical density |

| QC | Quality control |

References

- Daniel, I.; Oger, P.; Winter, R. Origins of life and biochemistry under high-pressure conditions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.; Dzwolak, W. Exploring the temperature-pressure configurational landscape of biomolecules: From lipid membranes to proteins. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2005, 363, 537–562, discussion 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R. Interrogating the Structural Dynamics and Energetics of Biomolecular Systems with Pressure Modulation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2019, 48, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oger, P.M.; Jebbar, M. The many ways of coping with pressure. Res. Microbiol. 2010, 161, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oglęcka, K.; Rangamani, P.; Liedberg, B.; Kraut, R.S.; Parikh, A.N. Oscillatory phase separation in giant lipid vesicles induced by transmembrane osmotic differentials. eLife 2014, 3, e03695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Stenhammar, J.; Wennerström, H.; Sparr, E. Vesicles Balance Osmotic Stress with Bending Energy That Can Be Released to Form Daughter Vesicles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worcester, D.L.; Weinrich, M. Hydrostatic Pressure Promotes Domain Formation in Model Lipid Raft Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4417–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Rangamani, P.; Liedberg, B.; Parikh, A.N. Mixing Water, Transducing Energy, and Shaping Membranes: Autonomously Self-Regulating Giant Vesicles. Langmuir 2016, 32, 2151–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabanon, M.; Ho, J.C.S.; Liedberg, B.; Parikh, A.N.; Rangamani, P. Pulsatile Lipid Vesicles under Osmotic Stress. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burruel, V.; Klooster, K.; Barker, C.M.; Pera, R.R.; Meyers, S. Abnormal early cleavage events predict early embryo demise: Sperm oxidative stress and early abnormal cleavage. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, H.; Xiong, Y.; Sun, P.; Xue, Y.; Li, K. Lipidomics profiles of human spermatozoa: Insights into capacitation and acrosome reaction using UPLC-MS-based approach. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1273878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.A. Seasonal variations of trimethylamine oxide and urea in the blood of a cold-adapted marine teleost, the rainbow smelt. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1994, 13, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.H.; Yancey, P.H. High contents of trimethylamine oxide correlating with depth in deep-sea teleost fishes, skates, and decapod crustaceans. Biol. Bull. 1999, 196, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibel, B.A.; Walsh, P.J. Trimethylamine oxide accumulation in marine animals: Relationship to acylglycerol storage. J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 205, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knop, J.M.; Mukherjee, S.; Jaworek, M.W.; Kriegler, S.; Manisegaran, M.; Fetahaj, Z.; Ostermeier, L.; Oliva, R.; Gault, S.; Cockell, C.S.; et al. Life in Multi-Extreme Environments: Brines, Osmotic and Hydrostatic Pressure—A Physicochemical View. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyas, A.; Wijayasinghe, Y.S.; Khan, I.; El Samaloty, N.M.; Adnan, M.; Dar, T.A.; Poddar, N.K.; Singh, L.R.; Sharma, H.; Khan, S. Implications of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and Betaine in Human Health: Beyond Being Osmoprotective Compounds. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 964624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolling, I.; Hölzl, C.; Imoto, S.; Alfarano, S.R.; Vondracek, H.; Knake, L.; Sebastiani, F.; Novelli, F.; Hoberg, C.; Brubach, J.B.; et al. Aqueous TMAO solution under high hydrostatic pressure. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 11355–11365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somero, G.N. Solutions: How adaptive changes in cellular fluids enable marine life to cope with abiotic stressors. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2022, 4, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufnal, M.; Zadlo, A.; Ostaszewski, R. TMAO: A small molecule of great expectations. Nutrition 2015, 31, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezón, F.A.; Stewart, K.R.; Schinckel, A.P.; Barnes, W.; Boyd, R.D.; Wilcock, P.; Woodliff, J. Effect of natural betaine on estimates of semen quality in mature AI boars during summer heat stress. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 170, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, M.; He, B. Protective Effects of Betaine on Boar Sperm Quality during Liquid Storage and Transport. Animals 2024, 14, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ratel, I.T.; Attia, K.A.H.; El-Raghi, A.A.; Fouda, S.F. Relief of the negative effects of heat stress on semen quality, reproductive efficiency and oxidative capacity of rabbit bucks using different natural antioxidants. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 34, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, H.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Weng, X. Plasma membrane lipid composition and metabolomics analysis of Yorkshire boar sperms with high and low resistance to cryopreservation. Theriogenology 2023, 206, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakop, U.; Müller, K.; Müller, P.; Neuhauser, S.; Callealta Rodríguez, I.; Grunewald, S.; Schiller, J.; Engel, K.M. Seminal lipid profiling and antioxidant capacity: A species comparison. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguenet, M.; Bouet, P.E.; Spiers, A.; Reynier, P.; May-Panloup, P. Mitochondria: Their role in spermatozoa and in male infertility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2021, 27, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlec, M.; Pintus, E.; Ros-Santaella, J.L. The Interaction of NO and H(2)S in Boar Spermatozoa under Oxidative Stress. Animals 2022, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Jones, K.T.; Robertson, S.A. Reactive oxygen species and sperm function–in sickness and in health. J. Androl. 2012, 33, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaciregui, M.; Luño, V.; González, N.; Domingo, P.; de Blas, I.; Gil, L. Chelating agents in combination with rosmarinic acid for boar sperm freeze-drying. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 17, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.; Zini, A.; Dyachenko, A.; Ciampi, A.; Carrell, D.T. A systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effect of sperm DNA damage on in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome. Asian J. Androl. 2017, 19, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, H.C.; Dinh, T.T.N.; Hardcastle, M.L.; Gilmore, A.A.; Ugur, M.R.; Hitit, M.; Jousan, F.D.; Nicodemus, M.C.; Memili, E. Advancing Semen Evaluation Using Lipidomics. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 601794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, M.A.; Lamichhane, S.; Dickens, A.; McGlinchey, A.; Ribeiro, H.C.; Sen, P.; Wei, F.; Hyötyläinen, T.; Orešič, M. Systems biology approaches to study lipidomes in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Su, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Evaluation of lipidomic change in goat sperm after cryopreservation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1004683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlichnyy, V.; Müller, P.; Pomorski, T.G.; Schulze, M.; Schiller, J.; Müller, K. Metabolic incorporation of unsaturated fatty acids into boar spermatozoa lipids and de novo formation of diacylglycerols. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2014, 177, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, J.L.; Kolesnick, R.N. Sphingolipid signaling in gonadal development and function. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1999, 102, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, L.M.; Linardic, C.M.; Karolak, L.A.; Hannun, Y.A. Programmed cell death induced by ceramide. Science 1993, 259, 1769–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arribas, A.B.; Alonso, A.; Goñi, F.M. Cholesterol interactions with ceramide and sphingomyelin. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2016, 199, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, S.; O’Flaherty, C. Sphingolipids modulate redox signalling during human sperm capacitation. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 40, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barenholz, Y.; Thompson, T.E. Sphingomyelin: Biophysical aspects. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1999, 102, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, E.R.; Fragio, C. Diradylglycerols stimulate phospholipase A2 and subsequent exocytosis in ram spermatozoa. Evidence that the effect is not mediated via protein kinase C. Biochem. J. 1994, 297 Pt 1, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Cai, Y.; Kang, B.; Huang, J.; Li, B. High-coverage targeted lipidomics revealed dramatic lipid compositional changes in asthenozoospermic spermatozoa and inverse correlation of ganglioside GM3 with sperm motility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, T.; Yang, Y.; Diao, H.; Zheng, X.; Xie, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; et al. IKBA phosphorylation governs human sperm motility through ACC-mediated fatty acid beta-oxidation. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, B.M.; Fernández, L.G.; Ferrusola, C.O.; Salazar-Sandoval, C.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Martinez, H.R.; Tapia, J.A.; Morcuende, D.; Peña, F.J. Membrane lipids of the stallion spermatozoon in relation to sperm quality and susceptibility to lipid peroxidation. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2011, 46, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavilani, H.; Doosti, M.; Nourmohammadi, I.; Mahjub, H.; Vaisiraygani, A.; Salimi, S.; Hosseinipanah, S.M. Lipid composition of spermatozoa in normozoospermic and asthenozoospermic males. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2007, 77, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucio, C.F.; Brito, M.M.; Angrimani, D.; Belaz, K.; Morais, D.; Zampieri, D.; Losano, J.; Assumpção, M.; Nichi, M.; Eberlin, M.N.; et al. Lipid composition of the canine sperm plasma membrane as markers of sperm motility. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52 (Suppl. 2), 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Semen HP | 0 h | 48 h | 96 h | 144 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh group (0 mmol/L) | 0 kPa | 95.83 ± 1.63 * | 94.25 ± 2.51 * | 94.27 ± 2.20 * | 94.14 ± 1.56 * |

| Control group (0 mmol/L) | 105 kPa | 93.53 ± 1.18 # | 89.88 ± 1.97 # | 89.23 ± 2.58 # | 84.11 ± 4.39 # |

| 1 mmol/L TMAO | 105 kPa | 93.49 ± 1.16 # | 92.00 ± 1.36 *,# | 91.42 ± 2.46 *,# | 91.36 ± 1.35 *,# |

| 2 mmol/L TMAO | 105 kPa | 93.67 ± 1.58 # | 92.67 ± 1.78 * | 91.55 ± 1.80 *,# | 91.40 ± 2.02 *,# |

| 4 mmol/L TMAO | 105 kPa | 93.73 ± 1.91 # | 92.99 ± 1.95 * | 92.03 ± 1.08 *,# | 91.62 ± 2.19 *,# |

| 8 mmol/L TMAO | 105 kPa | 93.93 ± 2.25 # | 93.26 ± 1.85 * | 92.94 ± 1.22 * | 92.83 ± 2.23 * |

| 16 mmol/L TMAO | 105 kPa | 93.84 ± 2.17 # | 91.91 ± 1.77 *,# | 89.65 ± 2.83 # | 90.05 ± 1.68 *,# |

| 5 mmol/L BET | 105 kPa | 93.55 ± 1.22 # | 91.36 ± 2.27 # | 89.28 ± 2.61 # | 87.08 ± 3.08 *,# |

| 10 mmol/L BET | 105 kPa | 93.63 ± 2.24 # | 92.18 ± 2.78 *,# | 91.07 ± 1.55 # | 91.12 ± 1.38 *,# |

| 20 mmol/L BET | 105 kPa | 93.89 ± 1.87 # | 93.51 ± 1.51 * | 92.08 ± 2.27 *,# | 91.44 ± 1.35 *,# |

| 40 mmol/L BET | 105 kPa | 93.85 ± 1.67 # | 91.08 ± 2.15 # | 87.68 ± 2.37 # | 87.36 ± 1.15 *,# |

| 80 mmol/L BET | 105 kPa | 92.90 ± 0.57 # | 86.28 ± 3.82 *,# | 85.48 ± 5.09 *,# | 83.68 ± 3.31 # |

| Item | Fresh Group | Control Group | T Group | B Group | H Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma membrane integrity, % | 70.49 ± 1.42 * | 44.05 ± 4.11 # | 61.45 ± 1.78 *,# | 60.84 ± 3.84 *,# | 58.76 ± 2.52 *,# |

| Acrosome integrity, % | 95.93 ± 1.27 | 96.13 ± 1.57 | 96.36 ± 1.31 | 96.57 ± 1.24 | 95.88 ± 0.81 |

| Sperm viability, % | 91.95 ± 2.65 * | 84.14 ± 1.75 # | 90.36 ± 1.96 * | 90.27 ± 1.57 * | 89.69 ± 1.27 *,# |

| DFI, % | 17.21 ± 2.31 * | 21.98 ± 1.70 # | 18.73 ± 1.95 * | 17.69 ± 0.71 * | 18.17 ± 1.39 * |

| MMP | 4.47 ± 0.48 * | 3.29 ± 0.19 # | 4.19 ± 0.59 * | 4.34 ± 0.42 * | 4.37 ± 0.99 * |

| Item | Fresh Group | Control Group | T Group | B Group | H Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROS | 1.00 ± 0.07 * | 1.25 ± 0.06 # | 1.14 ± 0.05 *,# | 1.12 ± 0.06 *,# | 1.12 ± 0.04 *,# |

| T-AOC, mmol/L | 2.36 ± 0.11 * | 2.13 ± 0.06 # | 2.22 ± 0.07 # | 2.32 ± 0.07 * | 2.17 ± 0.09 # |

| NO, μmol/L | 2.1 ± 0.64 * | 3.55 ± 0.31 # | 2.36 ± 0.22 * | 2.59 ± 0.3 * | 2.42 ± 0.68 * |

| MDA, nmol/mg prot | 2.86 ± 0.46 * | 4.84 ± 0.5 # | 3.31 ± 0.47 * | 3.72 ± 0.57 * | 3.54 ± 0.41 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, C.; Lu, G.; Lin, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Teng, L.; Lin, X.; Li, F.; Huang, S.; Hu, C. Supplementation of Trimethylamine N-Oxide or Betaine in Semen Improves Quality of Boar Spermatozoa Stored at 17 °C Following Hydrostatic Pressure Stress. Life 2025, 15, 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15101606

Qin C, Lu G, Lin X, Wang Z, Yang S, Teng L, Lin X, Li F, Huang S, Hu C. Supplementation of Trimethylamine N-Oxide or Betaine in Semen Improves Quality of Boar Spermatozoa Stored at 17 °C Following Hydrostatic Pressure Stress. Life. 2025; 15(10):1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15101606

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Cheng, Guangyuan Lu, Xiao Lin, Zhongkai Wang, Shiyu Yang, Liqiong Teng, Xin Lin, Fangfang Li, Shouping Huang, and Chuanhuo Hu. 2025. "Supplementation of Trimethylamine N-Oxide or Betaine in Semen Improves Quality of Boar Spermatozoa Stored at 17 °C Following Hydrostatic Pressure Stress" Life 15, no. 10: 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15101606

APA StyleQin, C., Lu, G., Lin, X., Wang, Z., Yang, S., Teng, L., Lin, X., Li, F., Huang, S., & Hu, C. (2025). Supplementation of Trimethylamine N-Oxide or Betaine in Semen Improves Quality of Boar Spermatozoa Stored at 17 °C Following Hydrostatic Pressure Stress. Life, 15(10), 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15101606