Teledermatology for Common Inflammatory Skin Conditions: The Medicine of the Future?

Abstract

1. Introduction

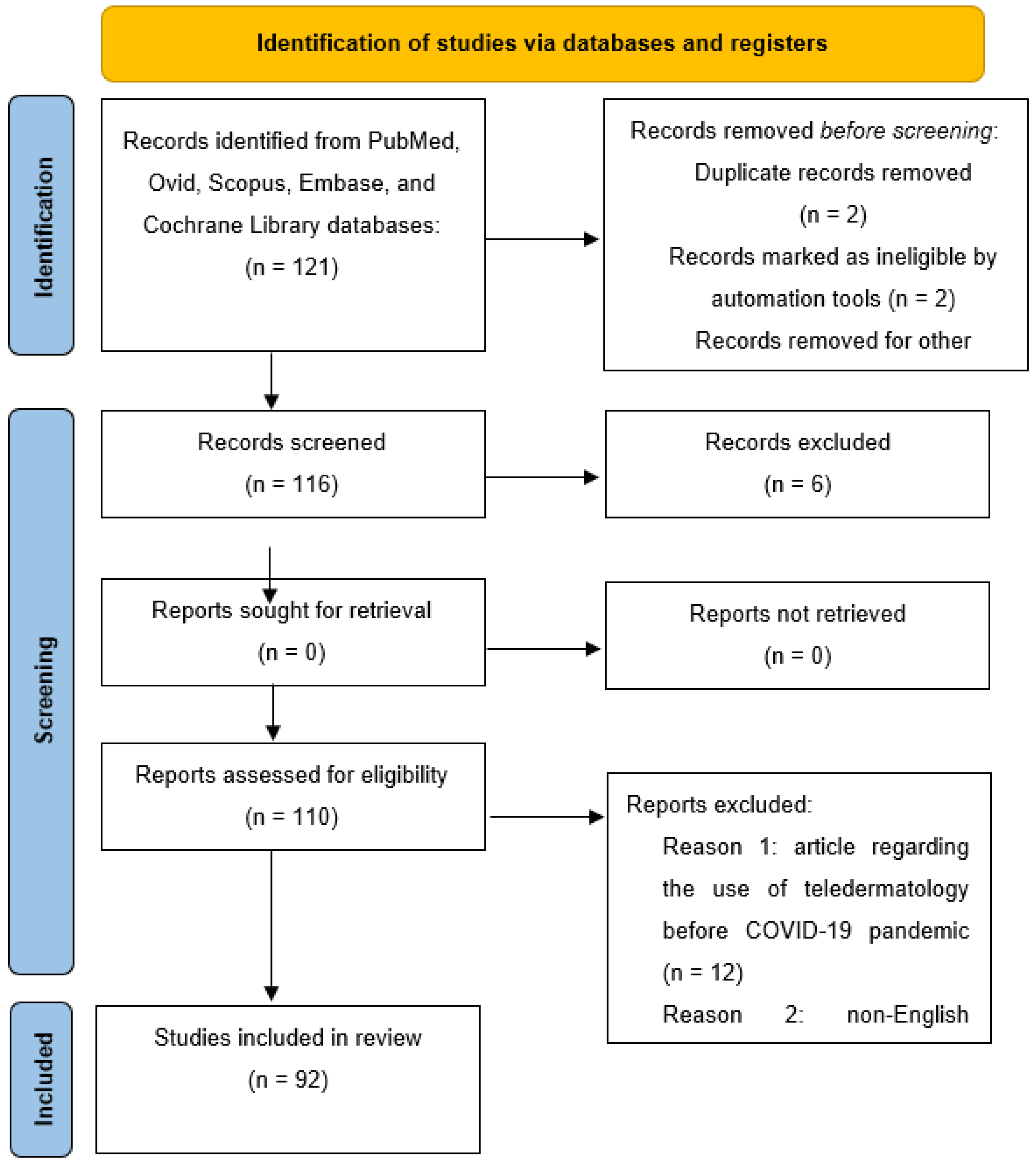

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Psoriasis

3.2. Acne and Hidradenitis Suppurativa

3.3. Atopic Dermatitis

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bashshur, R.; Shannon, G.; Krupinski, E.; Grigsby, J. The Taxonomy of Telemedicine. Telemed. e-Health 2011, 17, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquali, P.; Sonthalia, S.; Moreno-Ramirez, D.; Sharma, P.; Agrawal, M.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Arora, D. Teledermatology and its current perspective. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 11, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, A.; Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Villani, A.; Marasca, C.; Megna, M.; Fornaro, L.; Comune, R.; Potestio, L. The Role of Teledermatology during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 2785–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, A.; Megna, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Martora, F. Video and telephone teledermatology consultations during COVID-19 in comparison: Patient satisfaction, doubts and concerns. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1863–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, P.C.; Senner, S.; Frey, S.; Clanner-Engelshofen, B.M.; Frommherz, L.H.; French, L.E.; Reinholz, M. Teledermatology in times of COVID-19. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Marasca, C.; Battista, T.; Fabbrocini, G.; Ruggiero, A. Management of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa during COVID-19 vaccination: An experience from southern Italy. Comment on: ‘Evaluating the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa’. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 2026–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Battista, T. COVID-19 and cutaneous manifestations: A review of the published literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Sanchez-Flores, X.; Yau, J.; Huang, J.T. Cutaneous Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Kaur, H.; Singh, K.; Sen, C.K. Cutaneous Manifestations of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Adv. Wound Care 2021, 10, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potestio, L.; Genco, L.; Villani, A.; Marasca, C.; Fabbrocini, G.; Fornaro, L.; Ruggiero, A.; Martora, F. Reply to ‘Cutaneous adverse effects of the available COVID-19 vaccines in India: A questionnaire-based study’ by Bawane J et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e863–e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanati, A.; Martina, E.; Offidani, A. The Challenge Arising from New Knowledge about Immune and Inflammatory Skin Diseases: Where We Are Today and Where We Are Going. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagaria, O.; Villani, A.; Ruggiero, A.; Potestio, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Gallo, L. New-onset lichen planus arising after COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picone, V.; Fabbrocini, G.; Martora, L.; Martora, F. A Case of New-Onset Lichen Planus after COVID-19 Vaccination. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, G.; Gironi, L.C.; Grada, A.; Kridin, K.; Finelli, R.; Buja, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Pigatto, P.D.M.; Savoia, P. COVID-19 related masks increase severity of both acne (maskne) and rosacea (mask rosacea): Multi-center, real-life, telemedical, and observational prospective study. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Annunziata, M.; Potestio, L. Maskne prevalence and risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e678–e680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Battista, T.; Marasca, C.; Genco, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Potestio, L. Cutaneous Reactions Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Review of the Current Literature. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 2369–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, R.M.; Singh, I.; Armstrong, A.W. Updates on treatment guidelines for psoriasis, atopic dermatitis (eczema), hidradenitis suppurativa, and acne/rosacea during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 26, qt0j5150df. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Potestio, L.; Camela, E.; Battista, T.; Fabbrocini, G.; Megna, M. The impact of COVID-19 infection on patients with psoriasis treated with biologics: An Italian experience. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 2280–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megna, M.; Potestio, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Cinelli, E. Tildrakizumab: A new therapeutic option for erythrodermic psoriasis? Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megna, M.; Potestio, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Camela, E. Treating psoriasis in the elderly: Biologics and small molecules. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2022, 22, 1503–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Picone, V.; Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Megna, M. Guselkumab, Risankizumab, and Tildrakizumab in the Management of Psoriasis: A Review of the Real-World Evidence. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marasca, C.; Fornaro, L.; Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Fabbrocini, G.; Megna, M. Onset of vitiligo in a psoriasis patient on ixekizumab. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e15102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megna, M.; Camela, E.; Villani, A.; Tajani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Potestio, L. Teledermatology: A useful tool also after COVID-19 era? J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 2309–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, J.; Fox, A.; Kammire, M.S.; Hollis, A.N.; Khairat, S. Assessing Patient Satisfaction with Teledermatology Implementation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 290, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeroushalmi, S.; Millan, S.; Nelson, K.; Sparks, A.; Friedman, A. Patient Perceptions and Satisfaction with Teledermatology during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey-Based Study. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2021, 20, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.K.; Jemec, G.B.E. Teledermatology management of difficult-to-treat dermatoses in the Faroe Islands. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2019, 28, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.; Hadeler, E.; Calume, A.; Gitlow, H.; Nouri, K. Teledermatology: Current indications and considerations for future use. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, C.J.; Parsi, K.K.; Schupp, C.; Armstrong, A.W. Patient-centered online management of psoriasis: A randomized controlled equivalency trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 66, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megna, M.; Potestio, L.; Battista, T.; Camela, E.; Genco, L.; Noto, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Martora, F. Immune response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in patients with psoriasis undergoing treatment with biologics. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 2310–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühauf, J.; Schwantzer, G.; Ambros-Rudolph, C.M.; Weger, W.; Ahlgrimm-Siess, V.; Salmhofer, W.; Hofmann-Wellenhof, R. Pilot study on the acceptance of mobile teledermatology for the home monitoring of high-need patients with psoriasis. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2012, 53, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julie, Z.Y.; Reynolds, R.V.; Olbricht, S.M.; McGee, J.S. Moving forward with teledermatology: Operational challenges of a hybrid in-person and virtual practice. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 39, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferwerda, M.; Van Beugen, S.; Van Burik, A.; Van Middendorp, H.; De Jong, E.M.G.J.; Van De Kerkhof, P.C.M.; Van Riel, P.L.C.M.; Evers, A.W.M. What patients think about E-health: Patients’ perspective on internet-based cognitive behavioral treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 32, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, A.R.; Gibbons, C.M.; Torres, J.; Kornmehl, H.A.; Singh, S.; Young, P.M.; Chambers, C.J.; Maverakis, E.; Dunnick, C.A.; Armstrong, A.W. Access to Dermatological Care with an Innovative Online Model for Psoriasis Management: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Telemed. e-Health 2019, 25, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Chambers, C.J.; Maverakis, E.; Cheng, M.Y.; Dunnick, C.A.; Chren, M.-M.; Gelfand, J.M.; Wong, D.J.; Gibbons, B.M.; Gibbons, C.M.; et al. Effectiveness of Online vs. In-Person Care for Adults with Psoriasis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e183062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisondi, P.; Bellinato, F.; Piaserico, S.; Di Leo, S.; Cazzaniga, S.; Naldi, L. Preference for Telemedicine versus In-Person Visit among Patients with Psoriasis Receiving Biological Drugs. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 11, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinio, P.A.; Melendres, J.M.; Chavez, C.P.; Agon, M.K.; Merilleno, A.S.; Balagat, R.; Tumalad, L.L.; Amado, A.G.C.; Rivera, F. Clinical profile and response to treatment of patients with psoriasis seen via teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. JAAD Int. 2022, 7, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, P.M.; Chen, A.Y.; Ford, A.R.; Cheng, M.Y.; Lane, C.J.; Armstrong, A.W. Effects of online care on functional and psychological outcomes in patients with psoriasis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 88, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Megna, M.; Annunziata, M.C.; Abategiovanni, L.; Scalvenzi, M.; Tajani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Villani, A. Teledermatology for acne during COVID-19: High patients’ satisfaction in spite of the emergency. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e662–e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atak, M.F.; Mendi, B.I.; Yildizhan, I.K.; Sanli, H.E.; Farabi, B. Isotretinoin Treatment Practices and Outcomes in Acne Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Single Center, Retrospective, Comparative Study. Dermatol. Pr. Concept. 2022, 12, e2022036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, H.M.; Almazan, T.; Craft, N.; David, C.V.; Eells, S.; Erfe, C.; Lazzaro, C.; Nguyen, K.; Preciado, K.; Tan, B.; et al. Using Network Oriented Research Assistant (NORA) Technology to Compare Digital Photographic with In-Person Assessment of Acne Vulgaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühauf, J.; Kröck, S.; Quehenberger, F.; Kopera, D.; Fink-Puches, R.; Komericki, P.; Pucher, S.; Arzberger, E.; Hofmann-Wellenhof, R. Mobile teledermatology helping patients control high-need acne: A randomized controlled trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, R.; Evankovich, M.R.; Liu, R.; Liu, A.; Moorhead, A.; Ferris, L.K.; Falo, L.D.; English, J.C. Utilization of Asynchronous and Synchronous Teledermatology in a Large Health Care System during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed. e-Health 2021, 27, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Ba, S.M.D.; Lipner, S.R.; Bs, L.G. Retrospective study of acne telemedicine and in-person visits at an academic center during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Duarte-Ferreras, M.A.; Ojeda-Vila, T.; García-Morales, I.; Conejo-Mir, M.D.; Fernández-Orland, A.; Sánchez-Del-Campo, A.I.; Eiris, N.; Carrizosa, A.M.; Ruiz-De-Casas, A.; et al. Telemedicine management of systemic therapy with isotretinoin of patients with moderate-to-severe acne during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal prospective feasibility study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 1186–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.S.; Kassamali, B.; Shah, N.; LaChance, A.; Nambudiri, V.E. Differences in virtual care utilization for acne by vulnerable populations during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 718–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Annunziata, M.C.; Megna, M.; Scalvenzi, M.; Fabbrocini, G. Long-term results of teledermatology for acne patients during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1356–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Martora, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. A Case of Pemphigus Vulgaris and Hidradenitis Suppurativa: May Systemic Steroids Be Considered in the Standard Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa? Ski. Appendage Disord. 2022, 8, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.P. Remote consultations for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single-centre experience. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.C.; Hsiao, J.; Shi, V.; Naik, H.B.; Lowes, M.A.; Alavi, A. Remote management of hidradenitis suppurativa in a pandemic era of COVID-19. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, e318–e320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Marasca, C.; Fabbrocini, G.; Villani, A.; Martora, F. Teledermatology in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa: Should we improve this service? J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Marasca, C.; Fabbrocini, G.; Ruggiero, A. Strategies adopted in a southern Italian referral centre to reduce adalimumab discontinuation: Comment on ‘Can we increase the drug survival time of biologic therapies in hidradenitis suppurativa?’. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1864–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. Hidradenitis suppurativa flares following COVID-19 vaccination: A case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 23, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, H.; Patel, N.P. Response to Martora et al’s “Hidradenitis suppurativa flares following COVID-19 vaccination: A case series”. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 25, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Marano, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. Paradoxical Hidradenitis Suppurativa during Biologic Therapy, an Emerging Challenge: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Rodriguez, L.; Montero-Vílchez, T.; Arias-Santiago, S.; Molina-Leyva, A. Paradoxical Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Patients Receiving TNF-α Inhibitors: Case Series, Systematic Review, and Case Meta-Analysis. Dermatology 2020, 236, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, M.M.F.; Megna, M.; Battista, T.; Potestio, L. Adalimumab, Ustekinumab, and Secukinumab in the Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Review of the Real-Life Experience. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, H.C.; Maul, J.-T.; Yao, Y.; Wu, J.J.; Thyssen, J.P.; Thomsen, S.F.; Egeberg, A. Drug Survival of Biologics in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidinger, S.; Novak, N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016, 387, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckers, I.A.G.; Mclean, S.; Linssen, S.; Mommers, M.; Van Schayck, C.P.; Sheikh, A. Investigating International Time Trends in the Incidence and Prevalence of Atopic Eczema 1990–2010: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Genco, L.; Martora, F.; Potestio, L.; Patruno, C. Rapid improvement in pruritus in atopic dermatitis patients treated with upadacitinib: A real-life experience. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1497–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantelli, M.; Martora, F.; Patruno, C.; Nappa, P.; Fabbrocini, G.; Napolitano, M. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: A case report. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ständer, S. Atopic Dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, D.G.; Uppal, S.; Chat, V.S.; Wu, J.J. Assessing the risk of dupilumab use for atopic dermatitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, e251–e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, M.; Maffei, M.; Patruno, C.; Leone, C.A.; Di Guida, A.; Potestio, L.; Scalvenzi, M.; Fabbrocini, G. Dupilumab effectiveness for the treatment of patients with concomitant atopic dermatitis and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e15120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patruno, C.; Potestio, L.; Scalvenzi, M.; Battista, T.; Raia, F.; Picone, V.; Fabbrocini, G.; Napolitano, M. Dupilumab for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis in special populations. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 3028–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Morelli, P.; Patruno, C. Role of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation in Inflammatory Chronic Skin Diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricardi, P.M.; Dramburg, S.; Alvarez-Perea, A.; Antolín-Amérigo, D.; Apfelbacher, C.; Atanaskovic-Markovic, M.; Berger, U.; Blaiss, M.S.; Blank, S.; Boni, E.; et al. The role of mobile health technologies in allergy care: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2020, 75, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasca, C.; Annunziata, M.C.; Camela, E.; Di Guida, A.; Fornaro, L.; Megna, M.; Napolitano, M.; Patruno, C.; Potestio, L.; Fabbrocini, G. Teledermatology and Inflammatory Skin Conditions during COVID-19 Era: New Perspectives and Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavina-Bianchi, M.; Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Santos, A.P.; Rizzo, L.V.; Cordioli, E. Accuracy and efficiency of telemedicine in atopic dermatitis. JAAD Int. 2020, 1, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragamin, A.; de Wijs, L.E.M.; Hijnen, D.; Arends, N.J.T.; Schuttelaar, M.L.A.; Pasmans, S.G.M.A.; Bronner, M.B. Care for children with atopic dermatitis in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from the first wave and implications for the future. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 1863–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Grendelmeier, P.; Takaoka, R.; Ahogo, K.; Belachew, W.; Brown, S.; Correia, J.; Correia, M.; Degboe, B.; Dorizy-Vuong, V.; Faye, O.; et al. Position Statement on Atopic Dermatitis in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current status and roadmap. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-Domínguez, A.; Rojas-Lechuga, M.J.; Alobid, I. Management of Allergic Diseases During COVID-19 Outbreak. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2021, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollenberg, A.; Flohr, C.; Simon, D.; Cork, M.; Thyssen, J.P.; Bieber, T.; De Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Weidinger, S.; Deleuran, M.; Taieb, A.; et al. European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis statement on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) infection and atopic dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e241–e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.J.; Qu, H.-Q.; Tian, L.; Duan, Z.; Hakonarson, H. COVID-19: Look to the Future, Learn from the Past. Viruses 2020, 12, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Dorrell, D.N.; Feldman, S.R.; Huang, W.W. The Impact of teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargava, S.; Sarkar, R.; Kroumpouzos, G. Mental distress in dermatologists during COVID-19 pandemic: Assessment and risk factors in a global, cross-sectional study. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendagorta, E.; Servera, G.; Nuño, A.; Gil, R.; Pérez-España, L.; Herranz, P. Direct-to-patient teledermatology during COVID-19 lockdown in a health district in Madrid, Spain: The EVIDE-19 pilot study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021, 112, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, D.C.; Madigan, L.M. Inpatient teledermatology in the era of COVID-19 and the importance of the complete skin examination. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 977–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, R.L.; Le, P.B.; Brodell, R.T.; Nahar, V.K. Evaluation of patient attitudes towards the technical experience of synchronous teledermatology in the era of COVID-19. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 769–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, W.; Chandy, R.; Ahmadzada, M.; Rao, B. Teledermatology after COVID-19: Key challenges ahead. Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 27, 13030/qt5xr0n44p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Mak, W.K.; Law, J.Y.; Santos, D.; Quek, S.C. Optimizing teledermatology: Looking beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, V.; Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marano, L. “Covid arm”: Abnormal side effect after Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, D.E.; Amerson, E.; Rosenbach, M.; Lipoff, J.B.; Moustafa, D.; Tyagi, A.; Desai, S.R.; French, L.E.; Lim, H.W.; Thiers, B.H.; et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: A registry-based study of 414 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Fornaro, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. Can COVID-19 cause atypical forms of pityriasis rosea refractory to conventional therapies? J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1292–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.H.; Hong, J.K.; Hong, S.A.; Li, K.; Yoo, K.H. Pityriasis Rosea Shortly after mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccination. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 114, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraldi, S.; Spigariolo, C.B. Pityriasis rosea and COVID-19. J. Med Virol. 2021, 93, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. Pityriasis rosea after Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine: A case series. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Villani, A.; Marasca, C.; Fabbrocini, G.; Potestio, L. Skin reaction after SARS-CoV-2 vaccines Reply to ‘cutaneous adverse reactions following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster dose: A real-life multicentre experience’. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e43–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avallone, G.; Cavallo, F.; Astrua, C.; Caldarola, G.; Conforti, C.; De Simone, C.; di Meo, N.; di Stefani, A.; Genovese, G.; Maronese, C.; et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster dose: A real-life multicentre experience. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e876–e879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Nappa, P.; Megna, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions of patients with rare diseases: An experience of a Southern Italy referral center. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, e237–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Nappa, P.; Megna, M. Reply to ‘Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2’ by Solimani et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e750–e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimani, F.; Mansour, Y.; Didona, D.; Dilling, A.; Ghoreschi, K.; Meier, K. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e649–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcinelli, F.; Lamberti, A.; Cota, C.; Rubegni, P.; Cinotti, E. Reply to ‘development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2’ by Solimani F et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e976–e978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martora, F.; Villani, A.; Battista, T.; Fabbrocini, G.; Potestio, L. COVID-19 vaccination and inflammatory skin diseases. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washrawirul, C.; Triwatcharikorn, J.; Phannajit, J.; Ullman, M.; Susantitaphong, P.; Rerknimitr, P. Global prevalence and clinical manifestations of cutaneous adverse reactions following COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1947–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaderi, K.; Golezar, M.H.; Mardani, A.; Mallah, M.A.; Moradi, B.; Kavoussi, H.; Shamsabadi, A.; Golezar, S. Cutaneous adverse reactions of COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, M.; Potestio, L.; Costanzo, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; Gallo, L. Scabies outbreak during COVID-19: An Italian experience. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 1307–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Martora, F.; Fornaro, F.; Scalvenzi, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Villani, A. Reply to ‘Impact of the French COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on newly diagnosed melanoma delay and severity’ by R. Molinier et al. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e130–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinier, R.; Roger, A.; Genet, B.; Blom, A.; Longvert, C.; Chaplain, L.; Fort, M.; Saiag, P.; Funck-Brentano, E. Impact of the French COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on newly diagnosed melanoma delay and severity. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, e164–e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, A.; Martora, F.; Fornaro, L.; Guerrasio, G.; di Vico, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Scalvenzi, M.; Villani, A. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on nonmelanoma skin cancers: Report of a Southern Italy referral centre. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 2024–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potestio, L.; Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Martora, F. Cutaneous reactions following booster dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination: What we should know? J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5339–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronese, C.A.; Zelin, E.; Avallone, G.; Moltrasio, C.; Romagnuolo, M.; Ribero, S.; Quaglino, P.; Marzano, A.V. Cutaneous vasculitis and vasculopathy in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 996288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potestio, L.; Fabbrocini, G.; D’Agostino, M.; Piscitelli, I.; Martora, F. Cutaneous reactions following COVID-19 vaccination: The evidence says “less fear”. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martora, F.; Fabbrocini, G.; Megna, M.; Scalvenzi, M.; Battista, T.; Villani, A.; Potestio, L. Teledermatology for Common Inflammatory Skin Conditions: The Medicine of the Future? Life 2023, 13, 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13041037

Martora F, Fabbrocini G, Megna M, Scalvenzi M, Battista T, Villani A, Potestio L. Teledermatology for Common Inflammatory Skin Conditions: The Medicine of the Future? Life. 2023; 13(4):1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13041037

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartora, Fabrizio, Gabriella Fabbrocini, Matteo Megna, Massimiliano Scalvenzi, Teresa Battista, Alessia Villani, and Luca Potestio. 2023. "Teledermatology for Common Inflammatory Skin Conditions: The Medicine of the Future?" Life 13, no. 4: 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13041037

APA StyleMartora, F., Fabbrocini, G., Megna, M., Scalvenzi, M., Battista, T., Villani, A., & Potestio, L. (2023). Teledermatology for Common Inflammatory Skin Conditions: The Medicine of the Future? Life, 13(4), 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13041037