Scar Ectopic Pregnancy as an Uncommon Site of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

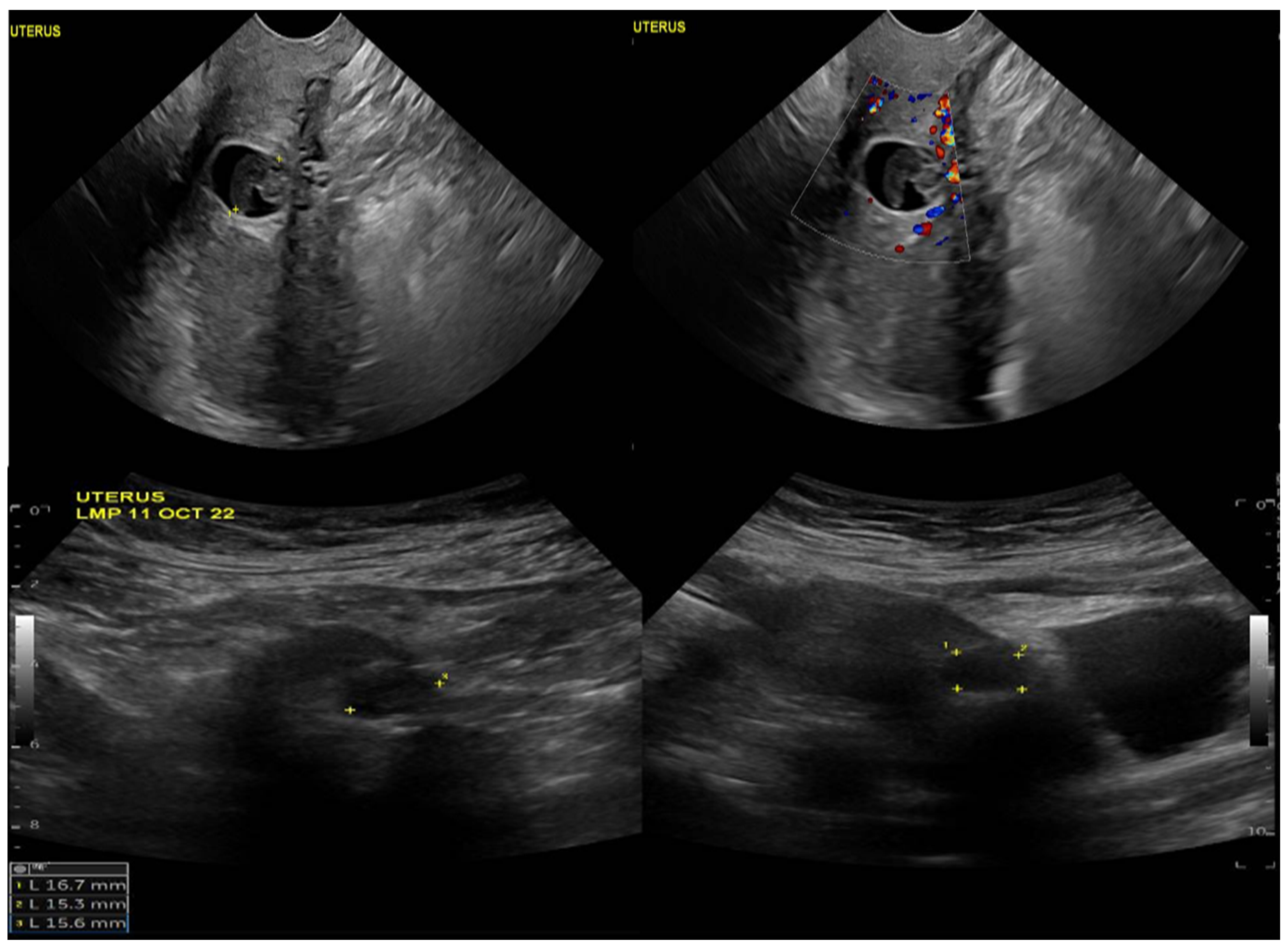

2. Case Description

3. Literature Review

Materials and Methods

4. Result

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thakur, B.; Shrimali, T. Rare Concomitant Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy with Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e37434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameel, K.; Abdul Mannan, G.; Niaz, R.; Hayat, D. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy: A Diagnostic and Management Challenge. Cureus 2021, 13, e14463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virdis, G.; Dessole, F.; Andrisani, A.; Vitagliano, A.; Cappadona, R.; Capobianco, G.; Cosmi, E.; Ambrosini, G.; Dessole, S. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Report of Three Cases and a Critical Review on the Management. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 46, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Soni, A.; Rana, S. Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy in Caesarean Section Scar: A Case Report. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 2012, 106892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asah-Opoku, K.; Oduro, N.E.; Swarray-Deen, A.; Mumuni, K.; Koranteng, I.O.; Senker, R.C.; Rijken, M.; Nkyekyer, K. Diagnostic and Management Challenges of Caesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy in a Lower Middle Income Country. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 2019, 4257696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Eeden, S.K.; Shan, J.; Bruce, C.; Glasser, M. Ectopic Pregnancy Rate and Treatment Utilization in a Large Managed Care Organization. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 105, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anant, M.; Paswan, A.; Jyoti, C. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy: The Lurking Danger in Post Cesarean Failed Medical Abortion. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2019, 13, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.A. Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2015, 65, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, K.-M.; Huang, L.-W.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yan-Sheng Lin, M.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Hwang, J.-L. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Issues in Management. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 23, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pędraszewski, P.; Wlaźlak, E.; Panek, W.; Surkont, G. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy—A New Challenge for Obstetricians. J. Ultrason. 2018, 18, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivalingam, V.N.; Duncan, W.C.; Kirk, E.; Shephard, L.A.; Horne, A.W. Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2011, 37, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, K.M.; Boulet, S.L.; Kissin, D.M.; Jamieson, D.J. Risk of Ectopic Pregnancy Associated with Assisted Reproductive Technology in the United States, 2001–2011. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moini, A.; Hosseini, R.; Jahangiri, N.; Shiva, M.; Akhoond, M.R. Risk Factors for Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case-Control Study. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumari, V.; Kumar, H.; Datta, M.R. The Importance of Ectopic Mindedness: Scar Ectopic Pregnancy, a Diagnostic Dilemma. Cureus 2021, 13, e13089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaden, M.; Maharaj, A.; Muzzi, K.; Paudel, K.; Haas, C.J. A Large Unruptured Ectopic Pregnancy. Radiol. Case Rep. 2021, 16, 1204–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getaneh Tadesse, W. Caesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. In Non-Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic, D.; Hillaby, K.; Woelfer, B.; Lawrence, A.; Salim, R.; Elson, C.J. First-Trimester Diagnosis and Management of Pregnancies Implanted into the Lower Uterine Segment Cesarean Section Scar. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 21, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmina, S. Clinical Analysis of Ectopic Pregnancies in a Tertiary Care Centre in Southern India: A Six-Year Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 2016, 10, QC13–QC16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, E.; BasicCetkovic, V.; Kozaric, H.; Rama, A. Ultrasound Evaluation of Uterine Scar After Cesarean Section. Acta Inform. Medica 2012, 20, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, T. Efficacy of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound for Diagnosis of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Type. Medicine 2019, 98, e17741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, D.K.; Bozkurt, M.; Sahin, L. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Addition to Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. J. Med. Cases 2014, 5, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, K.; Dai, Q. Differential Diagnosis of Cesarean Scar Pregnancies and Other Pregnancies Implanted in the Lower Uterus by Ultrasound Parameters. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8904507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, M.M.; Radfar, F. Management of a Viable Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Case Report. Oman Med. J. 2017, 32, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungkman, O.; Anderson, J. Importance of Early Detection of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. J. Diagnostic Med. Sonogr. 2015, 31, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majangara, R.; Madziyire, M.G.; Verenga, C.; Manase, M. Cesarean Section Scar Ectopic Pregnancy—A Management Conundrum: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2019, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, T.L.; Bembry, J.; Findley, A.D.; Yaklic, J.L.; Bhagavath, B.; Gagneux, P.; Lindheim, S.R. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy: Current Management Strategies. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2018, 73, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiravani, Z.; Atbaei, S.; Namavar Jahromi, B.; Hajisafari Tafti, M.; Moradi Alamdarloo, S.; Poordast, T.; Noori, A.; Forouhari, S.; Sabetian, S. Comparing Four Different Methods for the Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2022, 20, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, H.; Hamdi, I.; Rathi, B. Methotrexate Treatment of Ectopic Pregnancy: Experience at Nizwa Hospital with Literature Review. Oman Med. J. 2011, 26, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Luo, Y.; Huang, J. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy with Expectant Management. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, H. Diagnosis and Treatment of Ectopic Pregnancy. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 173, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerday, A.; Lourtie, A.; Pirard, C.; Laurent, P.; Wyns, C.; Jadoul, P.; Squifflet, J.-L.; Dolmans, M.-M.; Van Gossum, J.-P.; Hammer, F.; et al. Experience with Medical Treatment of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy (CSEP) with Local Ultrasound-Guided Injection of Methotrexate. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 564764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skubisz, M.M.; Tong, S. The Evolution of Methotrexate as a Treatment for Ectopic Pregnancy and Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia: A Review. ISRN Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 2012, 637094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Guan, T.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, M.; Guan, Z.; Li, G.; Zhu, Z.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, T.; et al. Role of Methotrexate Exposure in Apoptosis and Proliferation during Early Neurulation. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 34, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudeček, R.; Felsingerová, Z.; Felsinger, M.; Jandakova, E. Laparoscopic Treatment of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. J. Gynecol. Surg. 2014, 30, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huanxiao, Z.; Shuqin, C.; Hongye, J.; Hongzhe, X.; Gang, N.; Chengkang, X.; Xiaoming, G.; Shuzhong, Y. Transvaginal Hysterotomy for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy in 40 Consecutive Cases. Gynecol. Surg. 2015, 12, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lin, Y.; Xiong, C.; Dong, C.; Yu, J. Approaches in the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy and Risk Factors for Intraoperative Hemorrhage: A Retrospective Study. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 682368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Gadeeb, S.; Al Gadeeb, M.; Al Matrouk, J.; Faisal, Z.; Mohamed, A. Cesarean Scar—Unusual Site of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report. Cureus 2019, 11, e5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Agrawal, K.; Solanki, M.; Yadav, K.; Saini, R. A Rare Case of Scar Site Ectopic Pregnancy. Int. J. Anat. Radiol. Surg. 2022, 11, RI01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharode, A.; Chaudhari, K.; Inamdar, S. Caesarean Scar-Unusual Site of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Rare Case Report. Int. J. Reprod. Contraception, Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika; Gupta, W.; Wahi, S. A Rare Case Report of Caesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 2017, 11, QD10–QD11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leite, J.F.; Fraietta, R.; Elito Júnior, J. Local Management with Methotrexate of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy with Live Embryo Guided by Transvaginal Ultrasound: A Case Report. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2016, 62, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouni Mindjah, Y.A.; Essiben, F.; Foumane, P.; Dohbit, J.S.; Mboudou, E.T. Risk Factors for Ectopic Pregnancy in a Population of Cameroonian Women: A Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maymon, R.; Halperin, R.; Mendlovic, S.; Schneider, D.; Herman, A. Ectopic Pregnancies in a Caesarean Scar: Review of the Medical Approach to an Iatrogenic Complication. Hum. Reprod. Update 2004, 10, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morente, L.S.; León, A.I.G.; Reina, M.P.E.; Herrero, J.R.A.; Mesa, E.G.; López, J.S.J. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy—Case Series: Treatment Decision Algorithm and Success with Medical Treatment. Medicina 2021, 57, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Lu, X.; Qu, W.; Hao, Y.; Mao, Z.; Li, S.; Tao, G.; et al. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy Clinical Classification System with Recommended Surgical Strategy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 141, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-H.; Yang, S.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Jia, H.-Y.; Shi, M. Injection of MTX for the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Comparison between Different Methods. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 1867–1872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.-W.; Norwitz, G.A.; Pavlicev, M.; Tilburgs, T.; Simón, C.; Norwitz, E.R. Endometrial Decidualization: The Primary Driver of Pregnancy Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, J.; Robles, B.N.; Lluberas, N.M.A.; Audet, J.; Faustin, D.; Ruggiero, R. The Challenge of the Non-Compliant Patient: A Case of Caesarean Section Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjokroprawiro, B.A.; Akbar, M.I.A. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy with Devastating Profuse Vaginal Bleeding. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 2022, rjab566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Kaur, A. Transvaginal Ultrasonography in First Trimester of Pregnancy and Its Comparison with Transabdominal Ultrasonography. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2011, 3, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelekçi, S.; Aydoğmuş, S.; Aydoğmuş, H.; Eriş, S.; Demirel, E.; Şen Selim, H. Ineffectual Medical Treatment of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy with Systemic Methotrexate. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2014, 2, 232470961452890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilea, C.; Ilie, O.-D.; Marcu, O.-A.; Stoian, I.; Doroftei, B. The Very First Romanian Unruptured 13-Weeks Gestation Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy. Medicina 2022, 58, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundewar, T.; Pandurangi, M.; Reddy, N.S.; Vembu, R.; Andrews, C.; Nagireddy, S.; Soni, A.; Kakkad, V. Exclusive Use of Intrasac Potassium Chloride and Methotrexate for Treating Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Effectiveness and Subsequent Fecundity. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidar, Z.; Zadeh Modarres, S.; Abediasl, Z.; Khaghani, A.; Salehi, E.; Esfidani, T. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Treatment: A Case Series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvendag Guven, E.S.; Dilbaz, S.; Dilbaz, B.; Aykan Yildirim, B.; Akdag, D.; Haberal, A. Comparison of Single and Multiple Dose Methotrexate Therapy for Unruptured Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy: A Prospective Randomized Study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2010, 89, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, A.; Maleki, A.; HasanZadeh, K. Successful Management of Live Ectopic Pregnancy with High B-Hcg Titres by Systemic Methotrexate Injection: A Case Report. J. Women’s Health Dev. 2020, 03, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccone, G.; Mastantuoni, E.; Ferrara, C.; Sglavo, G.; Zizolfi, B.; De Angelis, M.C.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A. Hysteroscopic Resection vs Dilation and Evacuation for Treatment of Caesarean Scar Pregnancy: Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2022, 14, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commander, S.; Chamata, E.; Cox, J.; Dickey, R.; Lee, E. Update on Postsurgical Scar Management. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2016, 30, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, H.E.E.; Elderdery, A.Y.; Mohammed, R.R.; Omer, H.E.; Iman, A.M.; Tabein, E.M.; Ramadan, O.; Shaban, M. Pregnancy and Commonly Usage Hematological Medications in Sudan. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 9044–9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Kalburgi, S.; Thakur, Y.; Jadhav, J. Successful Hysteroscopy and Curettage of a Caesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e241183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Q. Hysteroscopy Combined with Laparoscopy in Treatment of Patients with Post-Cesarean Section Uterine Diverticulum. Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2019, 14, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, N.-J.; Andrews, R. Uterine Artery Embolization: A Safe and Effective, Minimally Invasive, Uterine-Sparing Treatment Option for Symptomatic Fibroids. Semin. Intervent. Radiol. 2008, 25, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr—Sasson, A.; Spira, M.; Rahav, R.; Manela, D.; Schiff, E.; Mazaki-Tovi, S.; Orvieto, R.; Sivan, E. Ovarian Reserve after Uterine Artery Embolization in Women with Morbidly Adherent Placenta: A Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano, N.; Reilly, J.; Moretti, M.; Lakhi, N. Double Balloon Cervical Ripening Catheter for Control of Massive Hemorrhage in a Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 2017, 9396075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsadaan, N.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Alqahtani, M.; Shaban, M.; Elsharkawy, N.B.; Abdelaziz, E.M.; Ali, S.I. Impacts of Integrating Family-Centered Care and Developmental Care Principles on Neonatal Neurodevelopmental Outcomes among High-Risk Neonates. Children 2023, 10, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Age | Diagnosis Method | Symptoms | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Al Gadeeb et al., 2019) [37] | 44 | Positive urine testing, transvaginal ultrasound examination, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). | Abdominal pain. | Intragestational sac injection of methotrexate. | The serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin level was undetectable on the 35th day after the methotrexate injection. |

| (Thakur & Shrimali, 2023) [1] | 27 | Pelviabdominal ultrasonography (U.S.G), which suggested a very early cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. | 1.5 months of amenorrhea and complaints of vaginal bleeding that lasted two days. | Under spinal anesthesia, dilatation and curettage were carried out. A surgically removed product of conception (POC). | After surgery, the patient’s condition improved, and she was discharged. |

| (Majangara et al., 2019) [25] | 36 | Transvaginal ultrasound imaging. | Abdominal pain. | Ectopic gestation was excised, and the uterus was repaired via laparotomy. | Improvement of the case. |

| (Yadav et al., 2022) [38] | 27 | b-hCG levels were 38,075.6 IU/L. Transvaginal ultrasonography was performed, which revealed a single gestational sac with a mean sac diameter of 2.7 mm, corresponding to the gestational age of four weeks and five days which was seen in lower uterine segment eccentric to the location of the previous scar site. | 1½ months amenorrhea with chief complaints of pain in abdomen and per vaginum spotting for three days. | The patient underwent laparoscopic resection. | A post procedure transvaginal ultrasound showed an absence of the gestational sac, and the patient was discharged without any complaints on postoperative day 2. At follow-up, the patient’s β-hCG level was 4 mIU/mL after 1½ months of her treatment. |

| (Kharode et al., 2022) [39] | 39 | Transvaginal sonography indicated an empty uterine cavity with well-defined endometrium. | Amenorrhea for 1.5 months; bleeding p/v (spotting) for 8 days. | Laparotomy. | Improvement of patient bleeding and abdominal pain. |

| (Deepika et al., 2017) [40] | 25 | Routine blood and urine investigations were normal. On admission, B-HCG level was 7118 IU/L, and after 48 h, the B-HCG value was 8108 IU/L, which showed less than doubling. Trans vaginal ultrasound revealed an empty uterine cavity; MRI of the pelvis showed a poorly defined heterogenous signal intensity space-occupying lesion of 30 × 23 mm, seen in myometrium. | Two-month amenorrhea with bleeding per vaginum on and off for 10–12 days. | Patient was planned for laparotomy. | Patient was followed up with serum Beta human Chorionic Gonadotropin (ß-hCG) level until B-HCG reached a non-pregnant level. |

| (Leite et al., 2016) [41] | 30 | β-hCG of 18,716, mIU/mL, Transvaginal ultrasound performed on this day showed a 6 mm crown to rump length (CRL), corresponding to a gestational age of 6 weeks and 4 days, a gestational sac of 16 × 14 × 9.6 mm located at the site of the previous cesarean section scar with a live embryo (126 bpm fetal heart rate), an empty uterine cavity, and attachments without changes. | 6 weeks late on her period, although presenting a small amount of vaginal bleeding for 1 day. | Transvaginal ultrasound-guided puncture and injection of methotrexate inside the gestational sac at 68 mg (1 mg/kg). | The patient remained in hospital until the last dose of folinic acid without clinical complications after the procedure, showing only slight abdominal colic treated with analgesia. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elawad, M.; Alyousef, S.Z.H.; Alkhaldi, N.K.; Alamri, F.A.; Bakhsh, H. Scar Ectopic Pregnancy as an Uncommon Site of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Life 2023, 13, 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13112151

Elawad M, Alyousef SZH, Alkhaldi NK, Alamri FA, Bakhsh H. Scar Ectopic Pregnancy as an Uncommon Site of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Life. 2023; 13(11):2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13112151

Chicago/Turabian StyleElawad, Mamoun, Suad Zaki Hamed Alyousef, Njoud Khaled Alkhaldi, Fayza Ahmed Alamri, and Hanadi Bakhsh. 2023. "Scar Ectopic Pregnancy as an Uncommon Site of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report and Literature Review" Life 13, no. 11: 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13112151

APA StyleElawad, M., Alyousef, S. Z. H., Alkhaldi, N. K., Alamri, F. A., & Bakhsh, H. (2023). Scar Ectopic Pregnancy as an Uncommon Site of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Life, 13(11), 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13112151