Design and Analysis of an Anti-Collision Spacer Ring and Installation Robot for Overhead Transmission Lines

Abstract

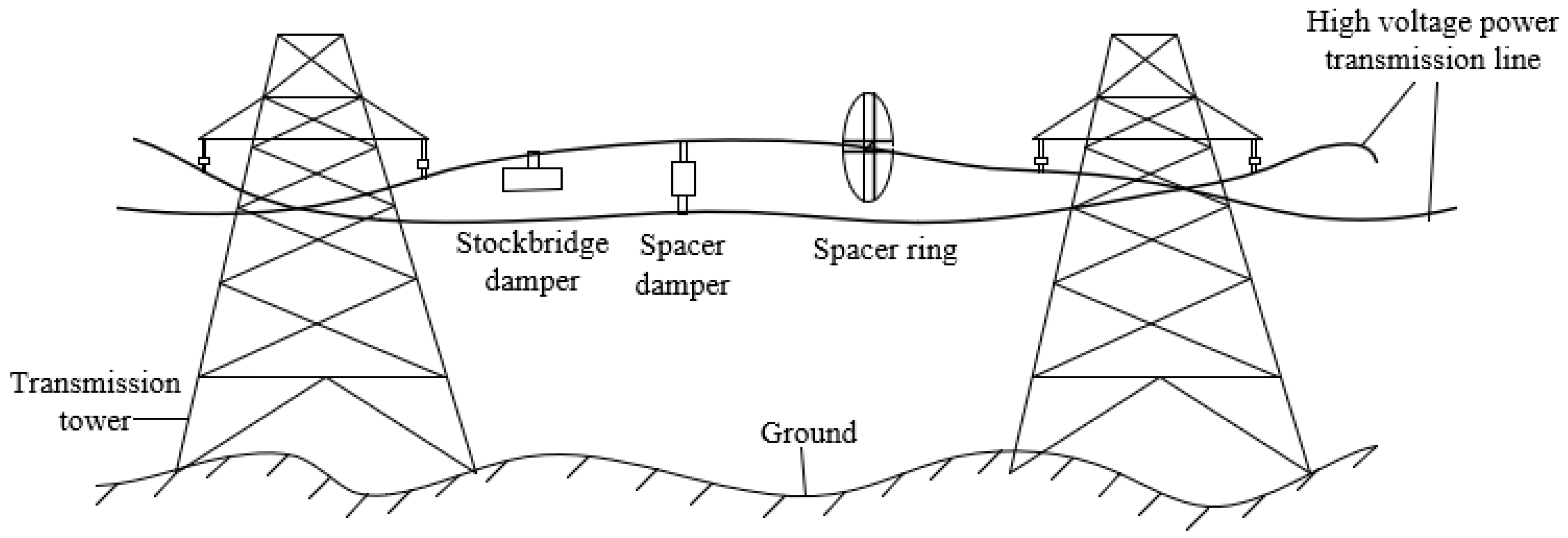

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A spacer ring and a teleoperated robot to address the installation challenges of anti-collision devices.

- (2)

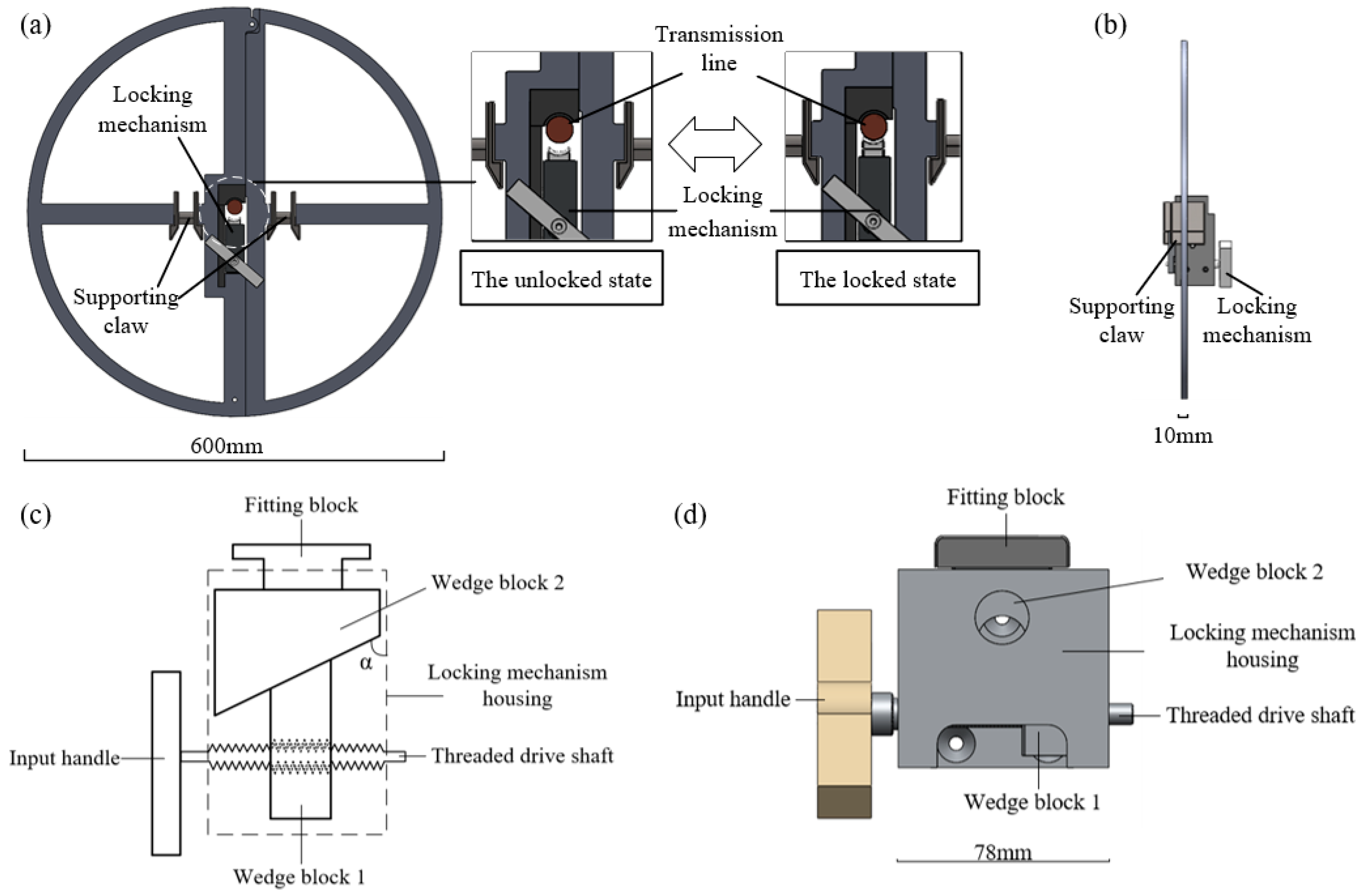

- A wedge-shaped locking mechanism that provides a strong output force.

2. Structure Design

2.1. Spacer Ring

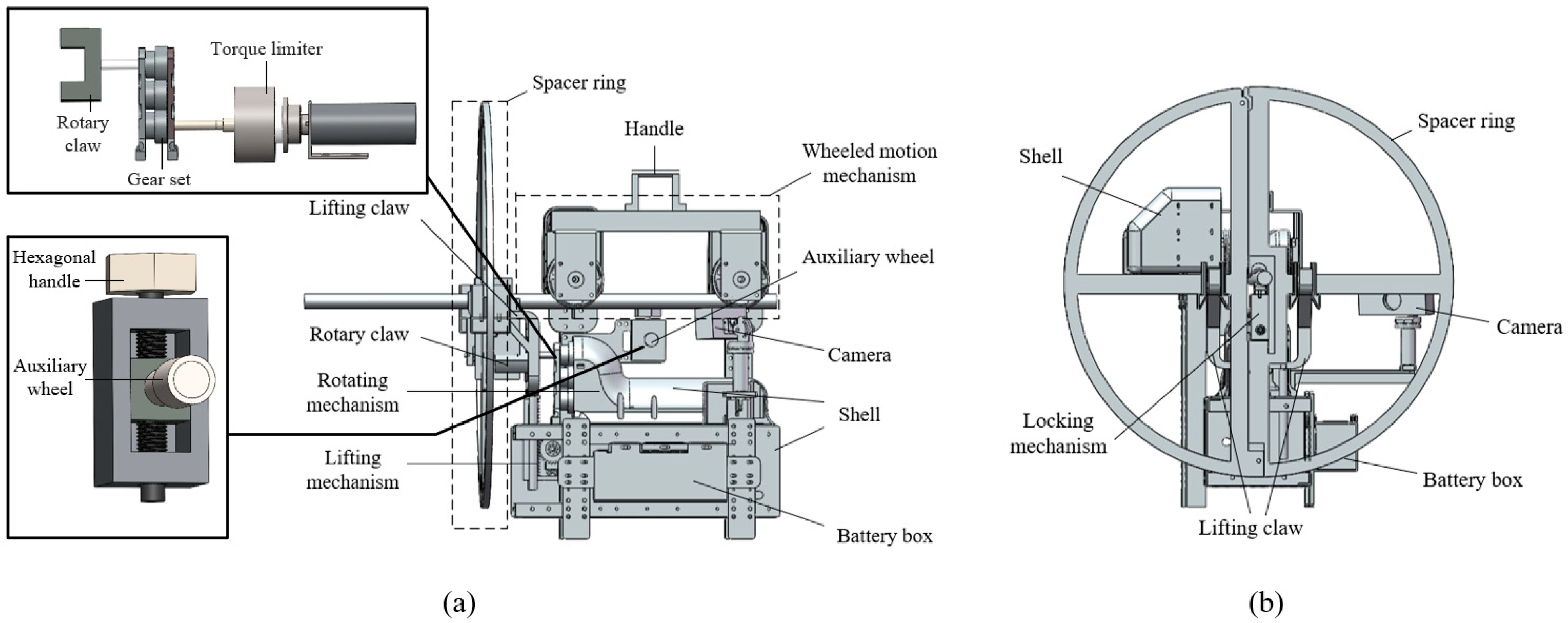

2.2. Spacer Ring Installation Robot

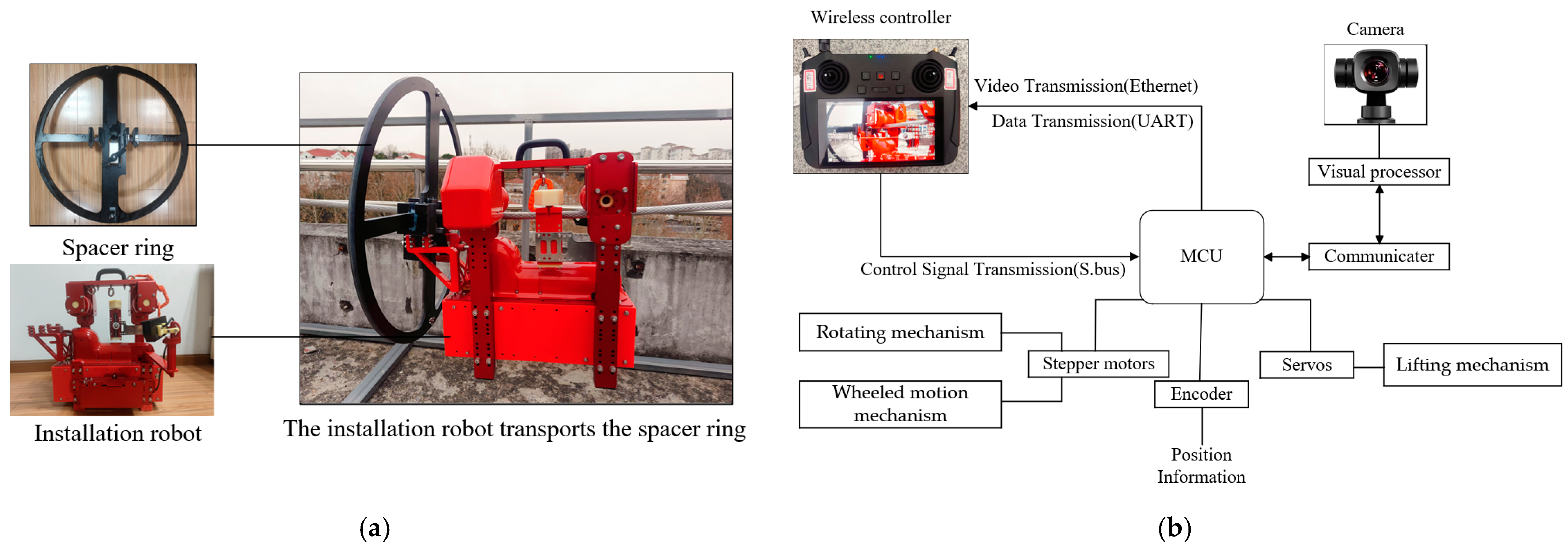

2.3. Prototypes of the Spacer Ring, Installation Robot and Control System

3. Modeling and Analysis

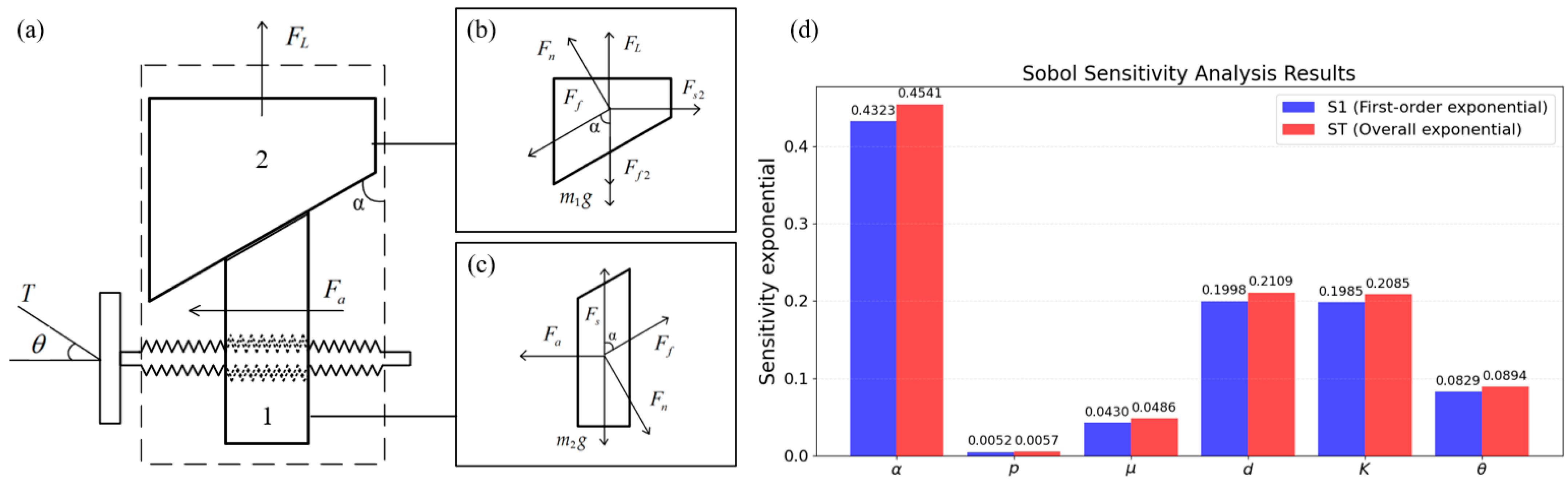

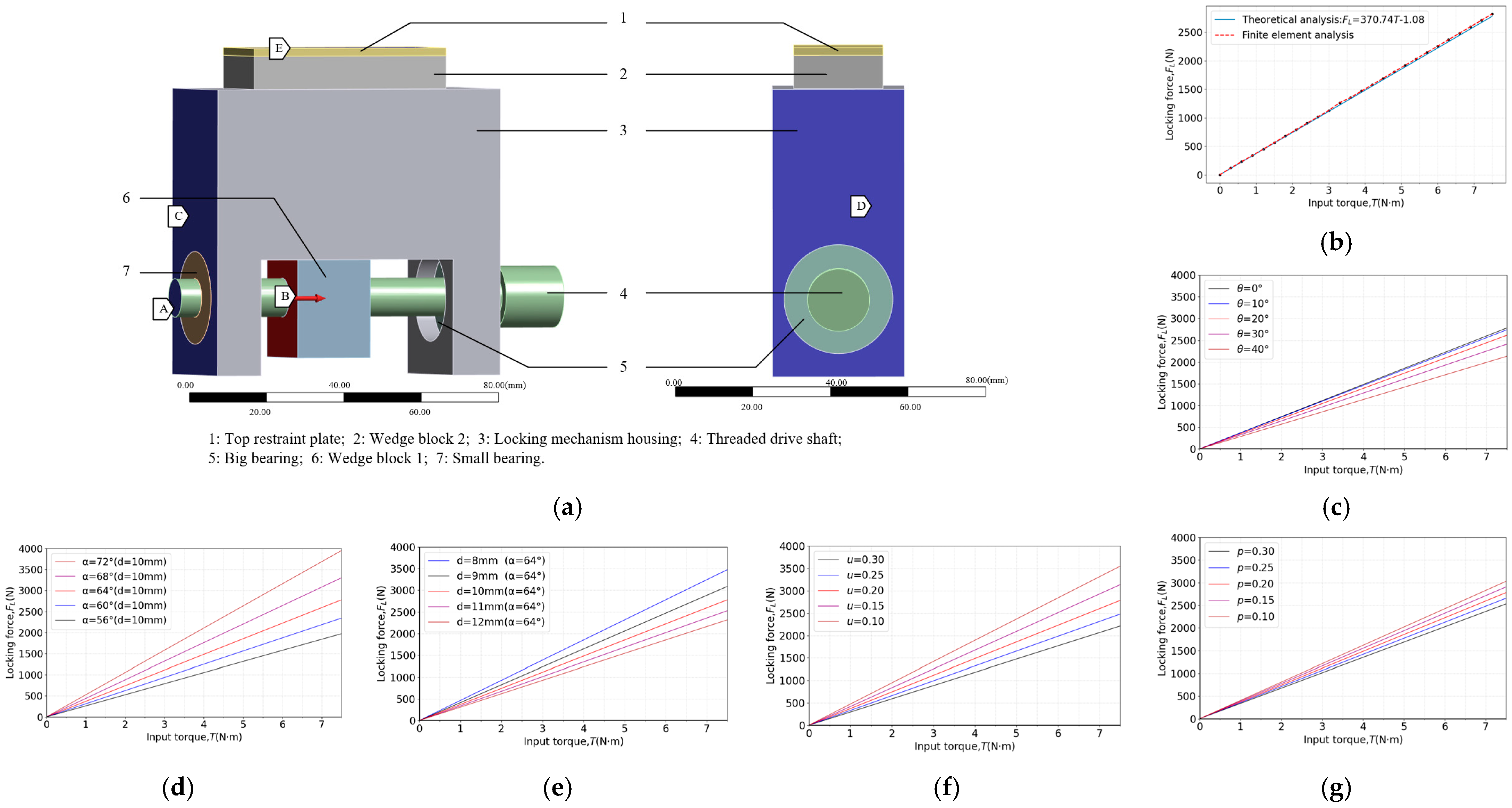

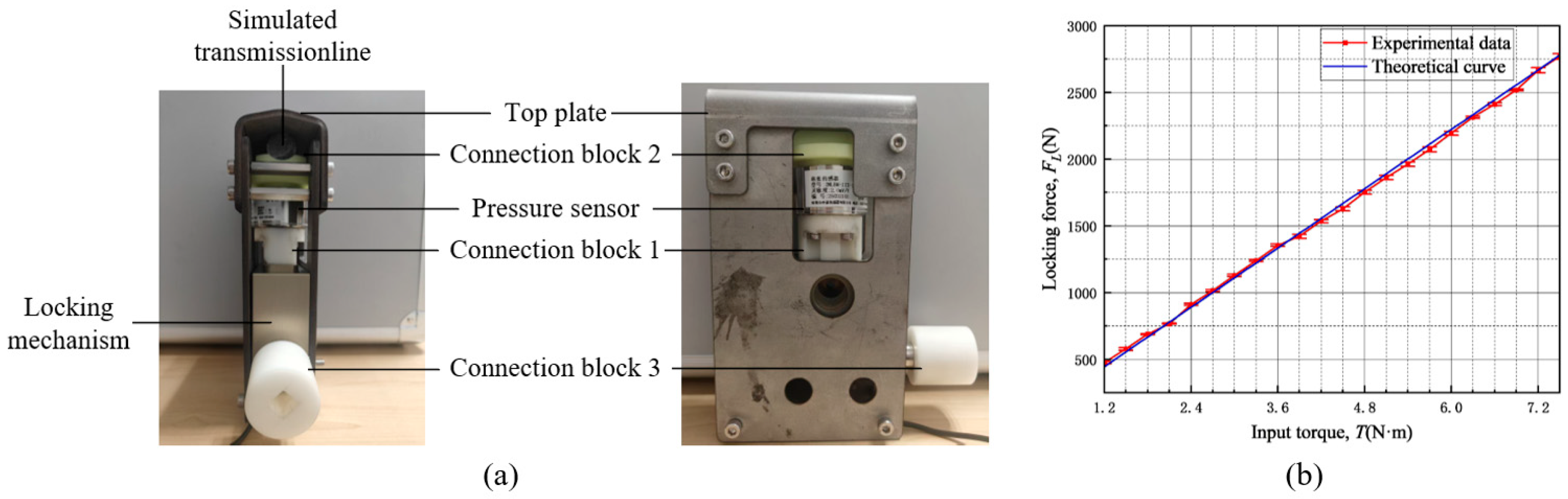

3.1. Output Force Analysis of the Locking Mechanism

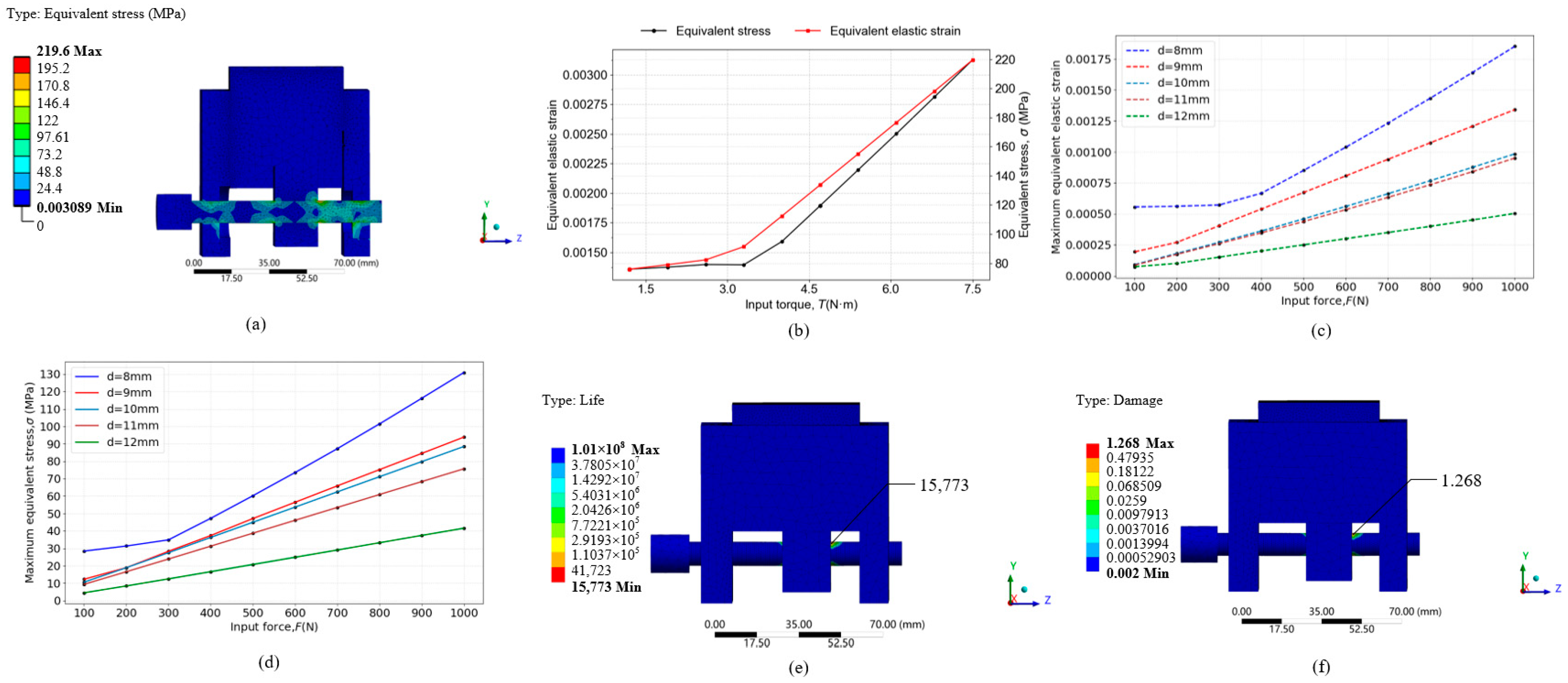

3.2. Static Stress Analysis of the Locking Mechanism

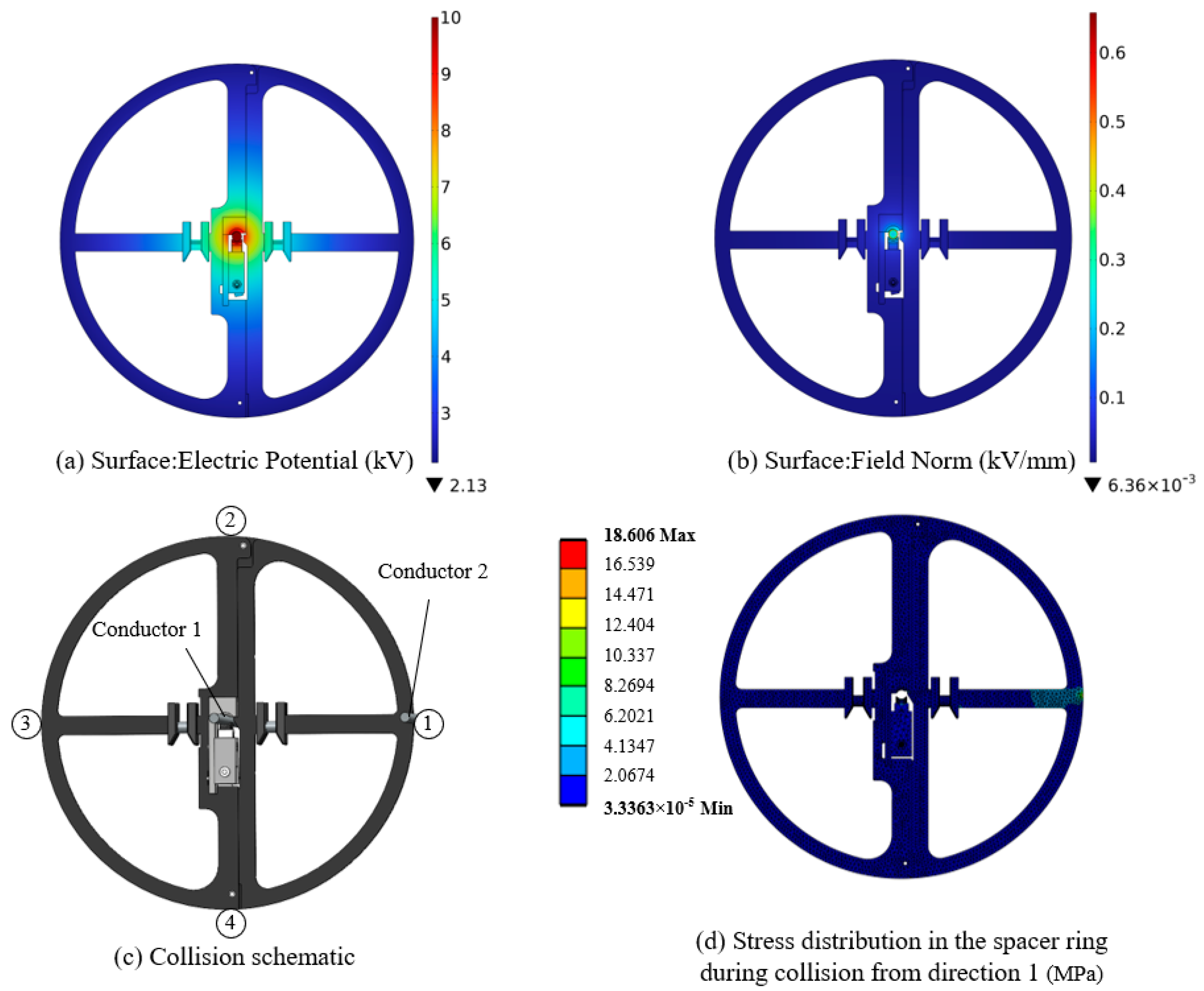

3.3. Electrical Performance and Collision Analysis of the Spacer Ring

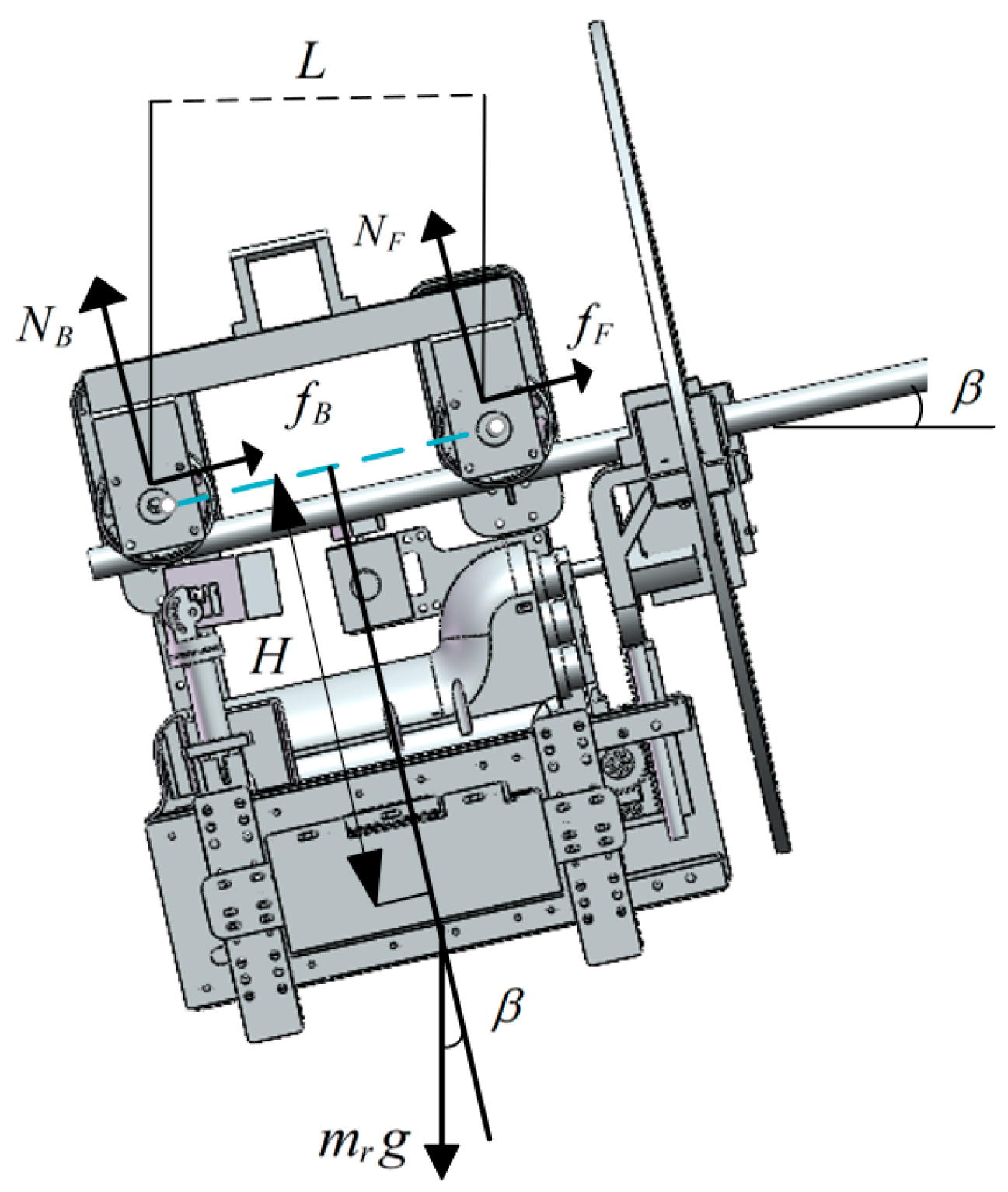

3.4. Climbing Analysis of the Installation Robot

4. Experiment

4.1. Experiment of Locking Force

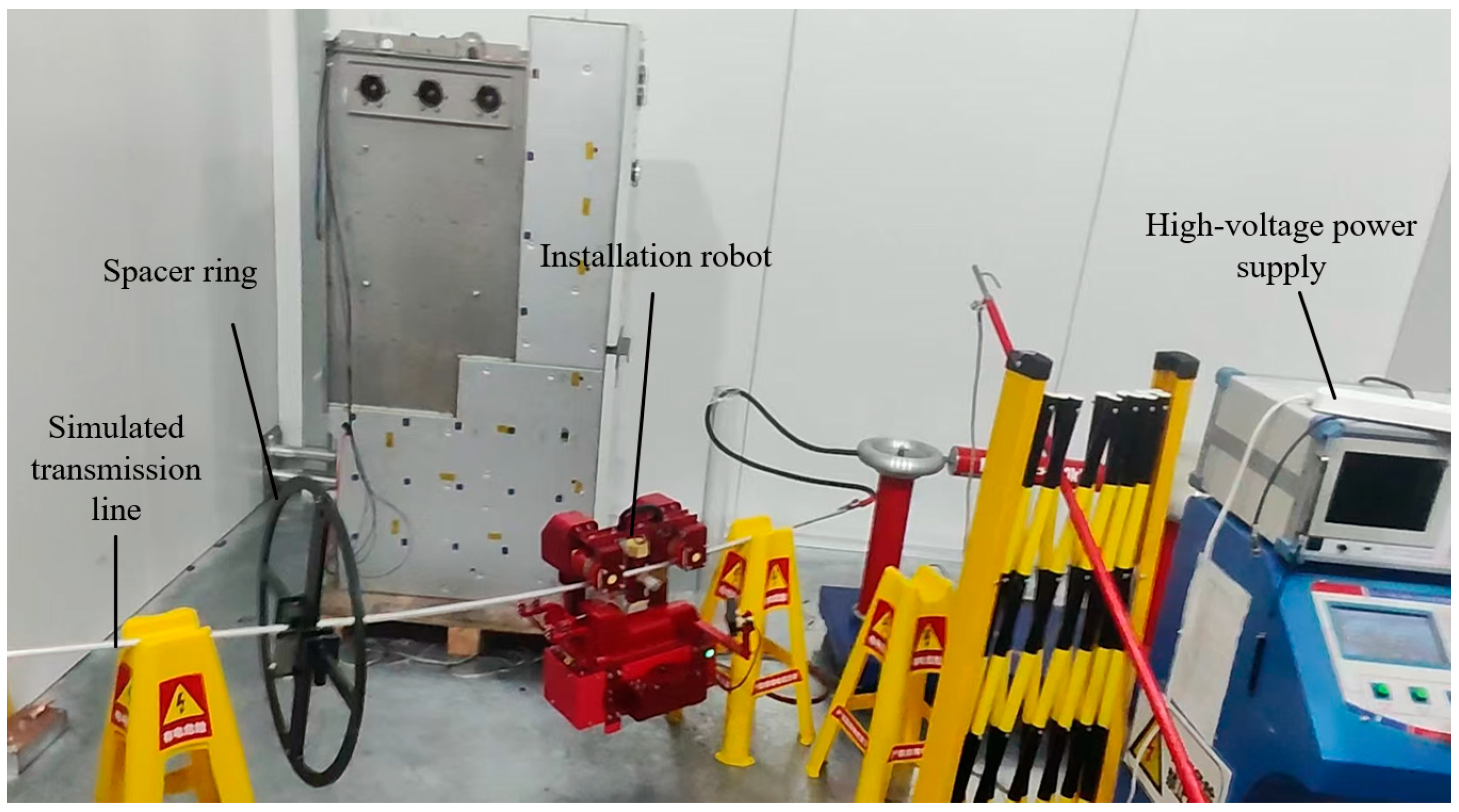

4.2. Indoor High-Voltage Tests

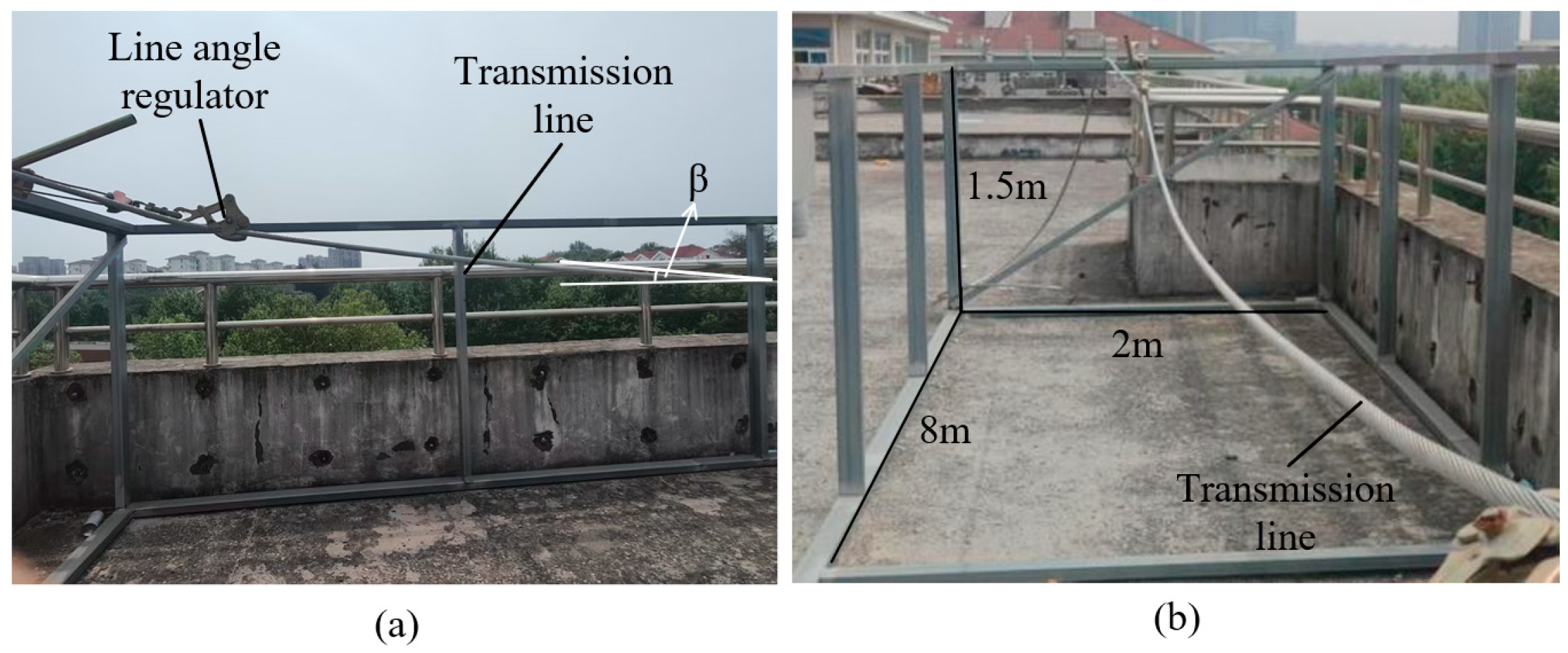

4.3. Outdoor Climbing Tests

4.4. Training Field Tests

4.5. Field Tests

4.6. Limitations of Experimental Scope

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nishihara, T.; Yagi, T. Aerodynamic modeling for large-amplitude galloping of four-bundled conductors. J. Fluids Struct. 2018, 82, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Zhang, S.; Huo, B.; Liu, X.; Zhou, A. Analysis of stability and modal interaction for multi-modal coupling galloping of iced transmission lines. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2021, 102, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumiya, H.; Yagi, T.; Macdonald, J.H. Unsteady aerodynamic force modelling for 3-DoF-galloping of four-bundled conductors. J. Fluids Struct. 2022, 112, 103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, A.T.; Erdemir, G.; Akinci, T.C.; Seker, S. Measurement of power line sagging using sensor data of a power line inspection robot. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 99198–99204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, Y.; Yu, P.; Popplewell, N.; Shah, A. Finite element modelling of transmission line galloping. Comput. Struct. 1995, 57, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Han, Y.; Yu, J.; Hu, P.; Cai, C. Anti-galloping analysis of iced quad bundle conductor based on compound damping cables. Eng. Struct. 2024, 306, 117831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Duan, C.; Liu, X.; Fan, D.; Ye, Z.; Xie, K.; Chai, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, J. Research on monitoring the transmission line tension and galloping based on FBG fitting sensor. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 7008108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Gao, X. Transmission line galloping prediction based on GA-BP-SVM combined method. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 107680–107687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhai, S.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.L.; Cheng, T. Multi-Parameters Self-Powered Monitoring via Triboelectric and Electromagnetic Mechanisms for Smart Transmission Lines. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2401710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhou, C.; Feng, X.; Deng, C.; Hu, W.; Xu, Y. Galloping Vibration Monitoring of Overhead Transmission Lines by Chirped FBG Array. Photonic Sens. 2022, 12, 220310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D. Design and Test of Quad-Bundle Spacer Damper Based on a New Rubber Structure. Shock Vibrat. 2023, 2023, 3828501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.; Yan, B.; Yang, H.; Wu, K.; Wu, C.; Yang, X. Study on anti-galloping efficiency of rotary clamp spacers for eight bundle conductor line. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 193, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Rui, X.; Liu, B.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S. Study on a new combined anti-galloping device for UHV overhead transmission lines. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2019, 34, 2070–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumiya, H.; Yukino, T.; Shimizu, M.; Nishihara, T. Field observation of galloping on four-bundled conductors and verification of countermeasure effect of loose spacers. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 220, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Richart, F.; da Silva, G.; Kowalski, E.; Ribeiro, S.; Dadam, A.; Munaro, M. Spacer design for 15 kv compact overhead distribution networks for regions with high environmental aggressiveness. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2018, 16, 2634–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, H.-N.; Li, J.-X.; Zhang, P. A pounding spacer damper and its application on transmission line subjected to fluctuating wind load. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2017, 24, e1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelwa, Y.; Swanson, A.; Dorrell, D.; Papailiou, K. A comparative study on high-voltage spacer-damper performance and assessment: Theory, experiments and analysis. SAIEE Afr. Res. J. 2019, 110, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, N.; Barbieri, R.; da Silva, R.A.; Mannala, M.J.; Barbieri, L.d.S.A.V. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of wire-rope isolator and Stockbridge damper. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 86, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, B.; He, Q.; Zhen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wen, S. Multi-parametric optimizations for power dissipation characteristics of Stockbridge dampers based on probability distribution of wind speed. Appl. Math. Model. 2019, 69, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbahce, E.; Gupta, S.K.; Barry, O. Position optimization of Stockbridge dampers under varying operating conditions: A comprehensive finite element and experimental analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 225, 112271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, G.; Manenti, A.; Pirotta, C.; Zuin, A. Stockbridge-type damper effectiveness evaluation. II. The influence of the impedance matrix terms on the energy dissipated. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2003, 18, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, D.; Hagedorn, P. On the hysteresis of wire cables in Stockbridge dampers. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2002, 37, 1453–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.-N.; Song, G. Aeolian vibration control of power transmission line using Stockbridge type dampers—A review. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2021, 21, 2130001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, O.; Zu, J.; Oguamanam, D. Analytical and experimental investigation of overhead transmission line vibration. J. Vib. Control. 2015, 21, 2825–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, O.; Long, R.; Oguamanam, D. Rational damping arrangement design for transmission lines vibrations: Analytical and experimental analysis. J. Dyn. Sys. Meas. Control 2017, 139, 051012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-J. Design sensitivity analysis of a Stockbridge damper to control resonant frequencies. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2017, 31, 4145–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, C.; Jiang, M.; Ma, Y.; Meng, F.; Shi, Q. The Innovative Design and Performance Testing of a Mobile Robot for the Automated Installation of Spacers on Six-Split Transmission Lines. Machines 2025, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa Peralta, P.; Palomino-Díaz, V.; Rodríguez Herrerías, P.; Rodríguez del Castillo, C.; Pedraza Cubero, C.M.; Yuste, J.P.; Aparicio Cillán, P.; Mesía López, R.; Águila Rodríguez, G.; Fernández Franco, V.P. ROSE: Robot for Automatic Spacer Installation in Overhead Power Lines. In Iberian Robotics Conference; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-K.; Cho, B.-H.; Oh, K.-Y. An inspection robot for live-line suspension insulator strings in 345-kV power lines. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2012, 27, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Mahammad, Z.; Sasank, P.; Badhwar, A.; Govindan, N. WireFlie: A Novel Obstacle-Overcoming Mechanism for Autonomous Transmission Line Inspection Drones. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 6528–6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, E.; Liang, Z.; Tan, M. A passive compliance obstacle-crossing robot for power line inspection and maintenance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2772–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Namiki, A.; Suzuki, S. Close-range transmission line inspection method for low-cost uav: Design and implementation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Jiang, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, A.; Zuo, G. Operation Motion Planning and Principle Prototype Design of Four-Wheel-Driven Mobile Robot for High-Voltage Double-Split Transmission Lines. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6195320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Simulation Modeling of Spacer Ring | Materials | Modulus of Elasticity/Mpa | Poisson’s Ratio | Density/(g/cm3) | Yield Strength/Mpa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spacer ring | Epoxy resin | 3780 | 0.35 | 1.16 | 54.6 |

| Locking mechanism | 7075 aluminum alloy | 71,000 | 0.33 | 2.81 | 455 |

| Bearings | 316 stainless steel | 193,000 | 0.28 | 8.03 | 205 |

| Transmission line | 6061 aluminum alloy | 69,040 | 0.33 | 2.713 | 259.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Lian, H.; Cheng, T. Design and Analysis of an Anti-Collision Spacer Ring and Installation Robot for Overhead Transmission Lines. Machines 2026, 14, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010023

Wang T, Lian H, Cheng T. Design and Analysis of an Anti-Collision Spacer Ring and Installation Robot for Overhead Transmission Lines. Machines. 2026; 14(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tianlei, Huize Lian, and Tianhui Cheng. 2026. "Design and Analysis of an Anti-Collision Spacer Ring and Installation Robot for Overhead Transmission Lines" Machines 14, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010023

APA StyleWang, T., Lian, H., & Cheng, T. (2026). Design and Analysis of an Anti-Collision Spacer Ring and Installation Robot for Overhead Transmission Lines. Machines, 14(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010023