One of the key factors restricting the operational efficiency of cranes is the payload oscillation during hoisting operations with wire–rope systems, which is induced by rope flexibility and acceleration-induced loads, thus preventing smooth and rapid cargo placement [

1]. Given the potential hazards and uncertainties associated with manual operation, efficient control methods need to be designed to enhance the control performance of boom crane systems and effectively suppress payload swing—a challenge that is difficult to overcome even for skilled operators [

2]. Previous studies have extensively examined crane systems and payload swing (oscillation) control from various perspectives, with notable findings. In 2019, Tayfun and Soyguder [

3] employed classical PID control, fuzzy logic control, and a PID-type fuzzy adaptive controller to regulate the system. In the same year, Dong-Hoon Lee [

4] et al. investigated methods for suppressing unexpected vertical vibration in the load, applying several control strategies, including PID control, sliding mode control, and feedback linearization. In 2020, Charles [

5] et al. represented the essential nonlinear dynamics of crane systems using a state-space fuzzy model with a compact rule base. In 2021, Christofer Bernardo [

6] et al. adopted fuzzy intelligent control for load anti-sway, combined with a classic proportional–derivative (PD) controller tuned via the Ziegler–Nichols method for trolley lateral positioning. Johan [

7] et al. derived hanging load dynamics and associated crane kinematics to develop a two-degrees-of-freedom anti-swing controller. Similarly, Die Hu [

8] et al. established a dynamic model for a dual-vessel crane system based on the Lagrangian formulation, proposing a controller capable of achieving precise dual-boom positioning while effectively eliminating payload swing. Luo Kai [

9] et al. numerically solved the nonlinear deformation displacement at the boom tip using differential equations and coordinate transformation. Subsequently, they proposed a hoisting-luffing coordination strategy based on a preset luffing cylinder extension length via a stepwise progressive approach. In 2022, Tian Gao [

10] et al. described frequency analyses of double-pendulum swing and twisting for eccentric loads. Huaitao Shi [

11] et al. proposed a novel nonlinear coupled tracking and anti-sway controller, which ensures stable trolley startup and operation by incorporating a smooth reference trajectory. In 2023, Bilgin and Melek [

12] designed an additional telescopic boom for anti-sway control, employing a Particle Swarm Optimization Proportional–Derivative–Second Derivative (PSO-PDD

2) control system. Fan Bo [

13] et al. developed a novel control strategy based on load-energy coupling by analyzing the coupling relationships among various state variables of the crane, achieving both system positioning and elimination of residual payload swing. Sun Mingxiao [

14] et al. proposed a PD-based trajectory tracking strategy that accounts for hoisting-length changes. In addressing the limitations of traditional anti-swing control algorithms in tackling ship-mounted crane operations—specifically, the neglect of coupling between rope length variation and swing angle—Yu [

15] et al. established a three-dimensional dynamic mathematical model of an overhead crane and investigated the dynamic characteristics of the swing angle. Their methodology provides a valuable reference for related research. Based on nonlinear dynamic modeling of a crane, Shenhao Tong [

16] et al. designed a novel variable-structure controller by partitioning the nonlinear system into two subsystems containing displacement and swing angle information. Based on the geometric parameters of a revolving offshore crane vessel, Dapeng Zhang [

17] et al. developed a corresponding marine crane model and investigated the motion responses of the suspended payload under various wave conditions. In 2024, Li Dong [

18] et al. proposed an adaptive coupled tracking and anti-swing control strategy, designing a controller for adaptive trajectory tracking. Wang Hongdu [

19] et al. developed an adaptive fuzzy disturbance observer (FDO)-based control scheme to suppress the swing of a mooring–heavy lift crane (HLC)–cargo system under wave disturbances. Segura [

20] et al. designed a novel robust observer-based proportionally retarded controller for perturbed two-dimensional crane systems, accounting for variable rope length. Tom Kusznir [

21] et al. proposed a novel nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC) approach to control an underactuated overhead crane system. In the same year, Jingzheng Lin [

22] et al. proposed a novel model predictive control (MPC) method that successfully accounted for constraints on both system inputs and outputs while maintaining satisfactory control performance even under persistent ship roll and heave disturbances. In 2025, Abut [

23] applied two distinct control methods to the system; the designed control algorithms aim to stabilize the pendulum arms in an upright position and drive the trolley to its equilibrium point.

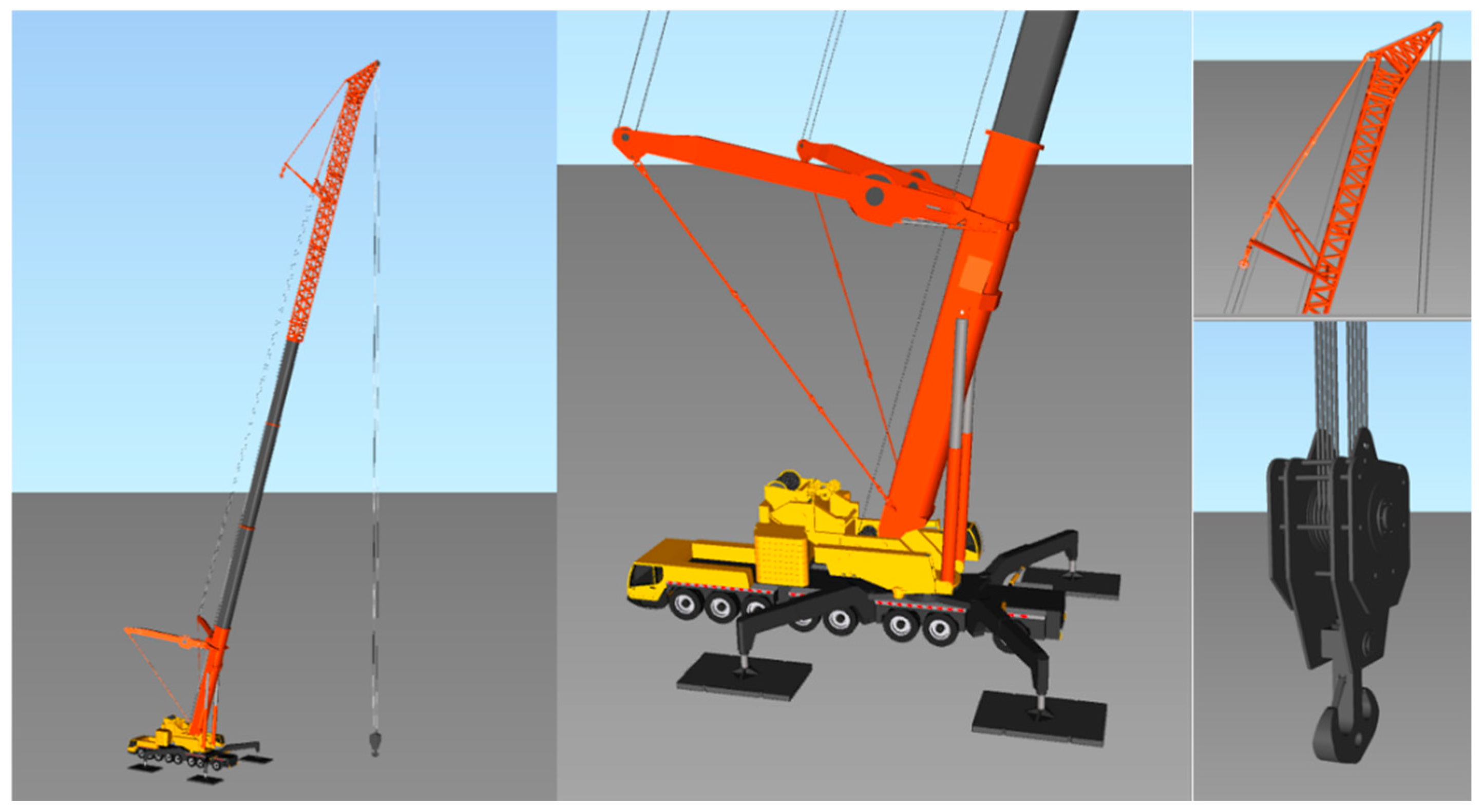

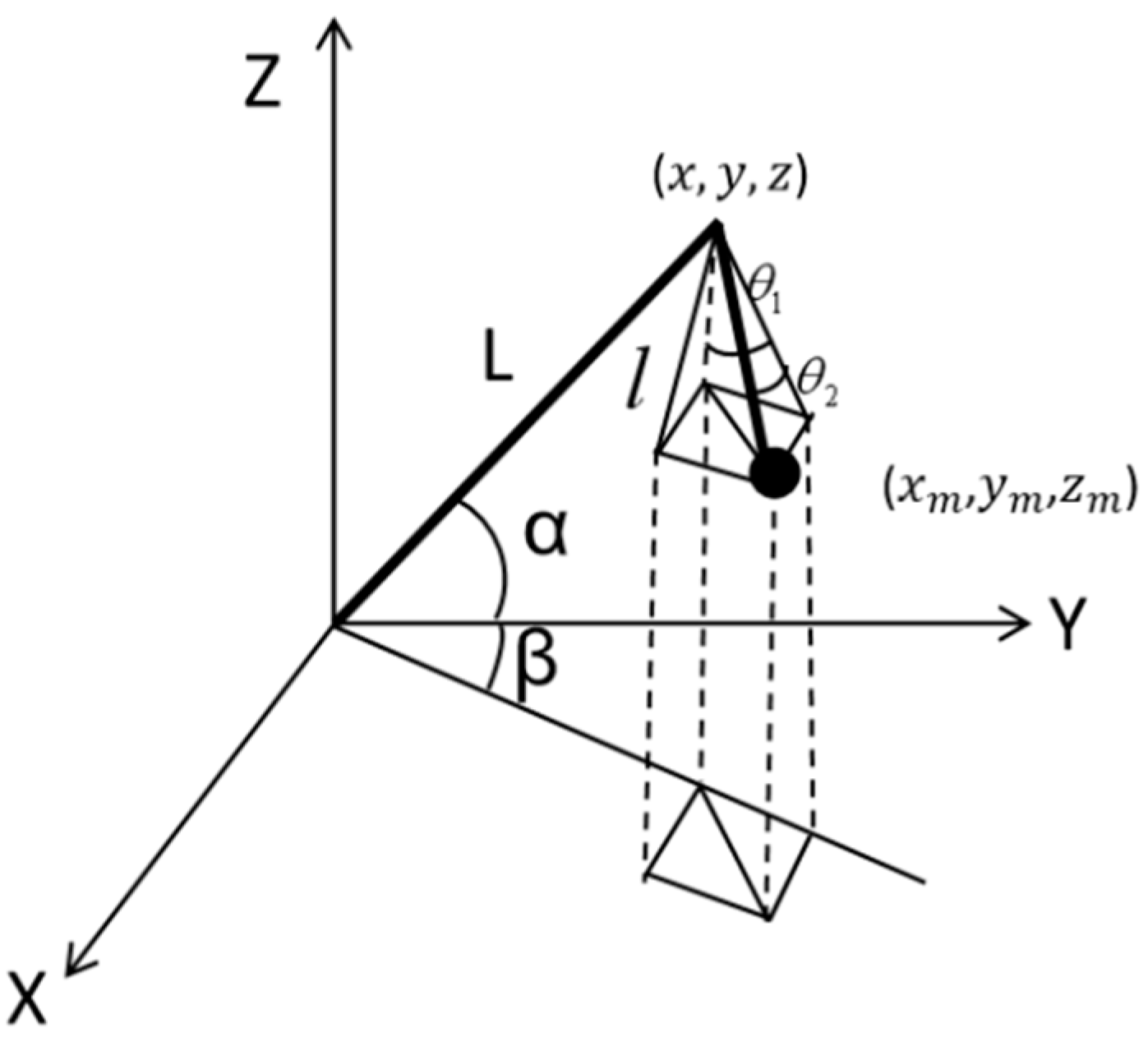

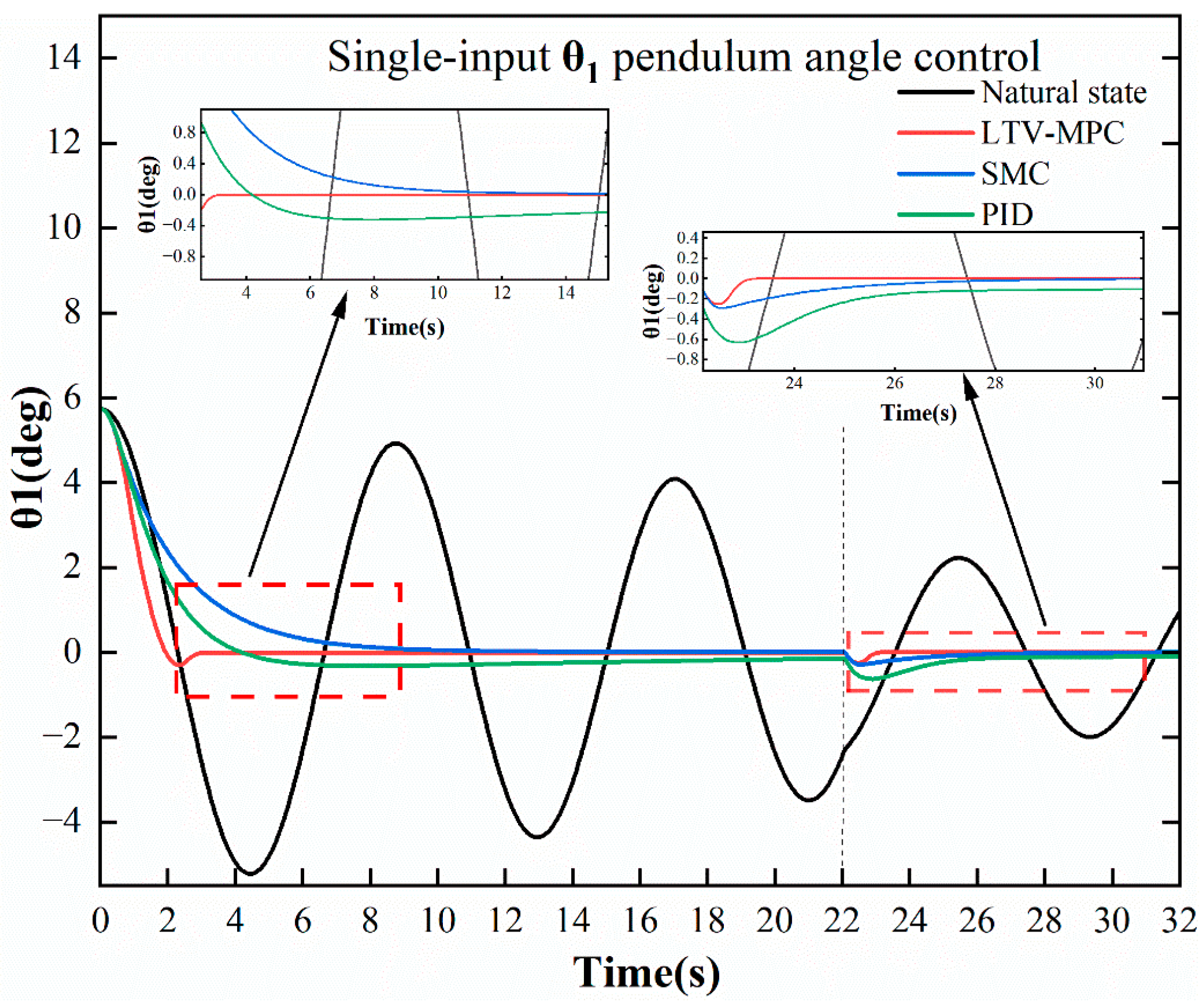

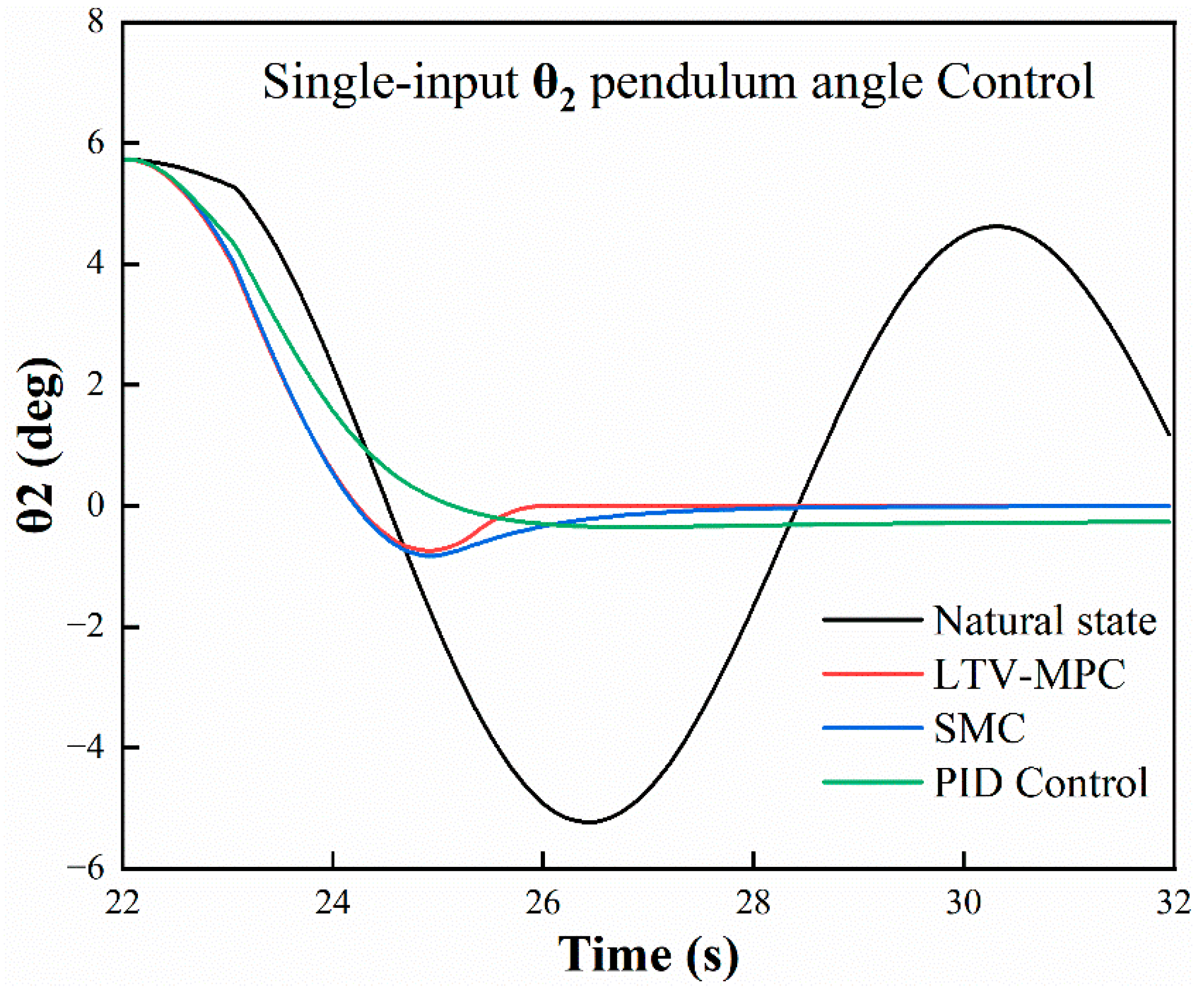

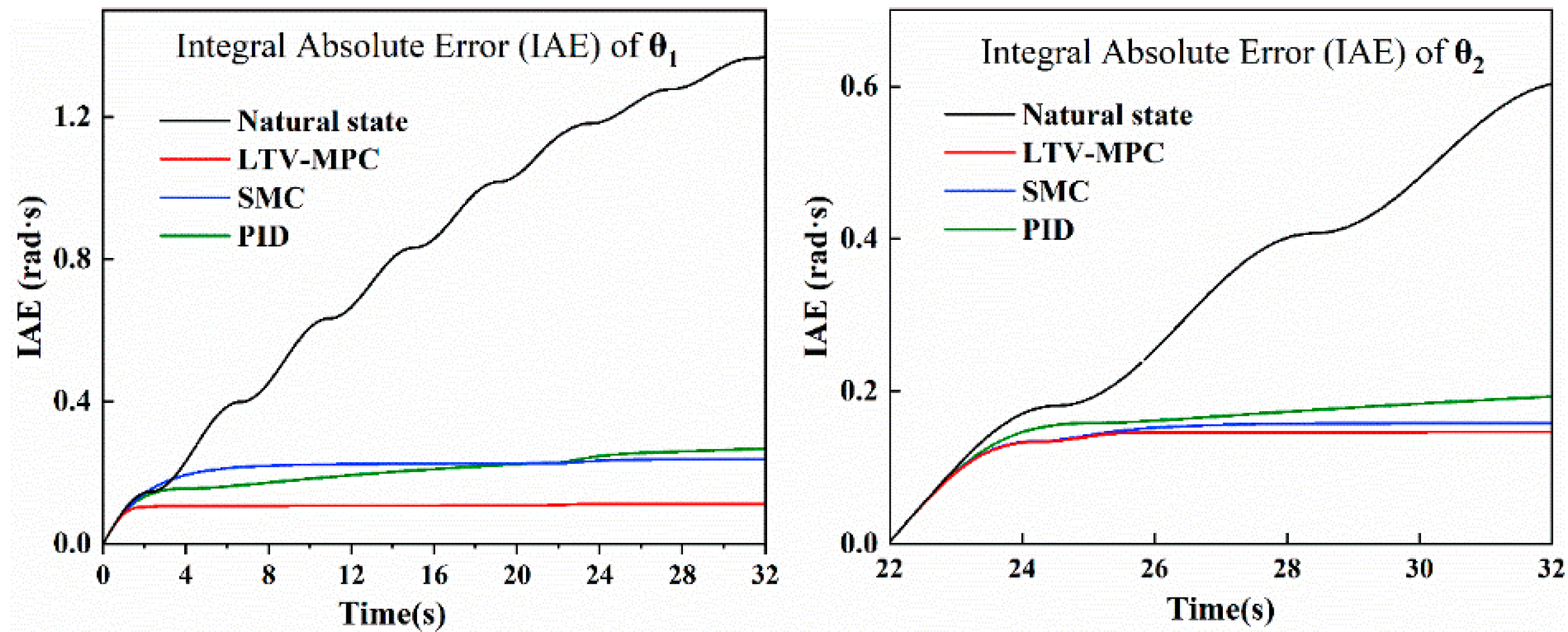

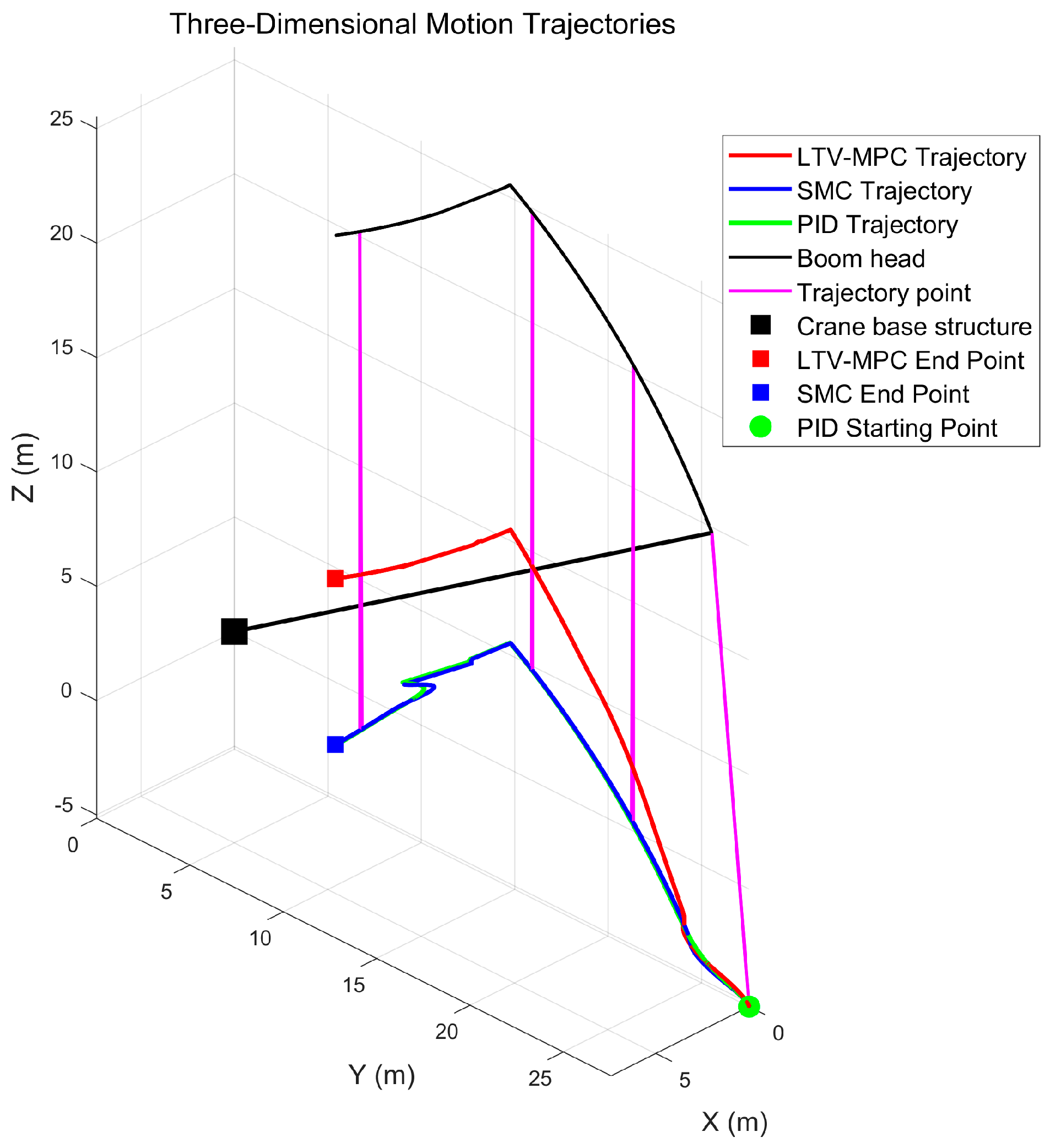

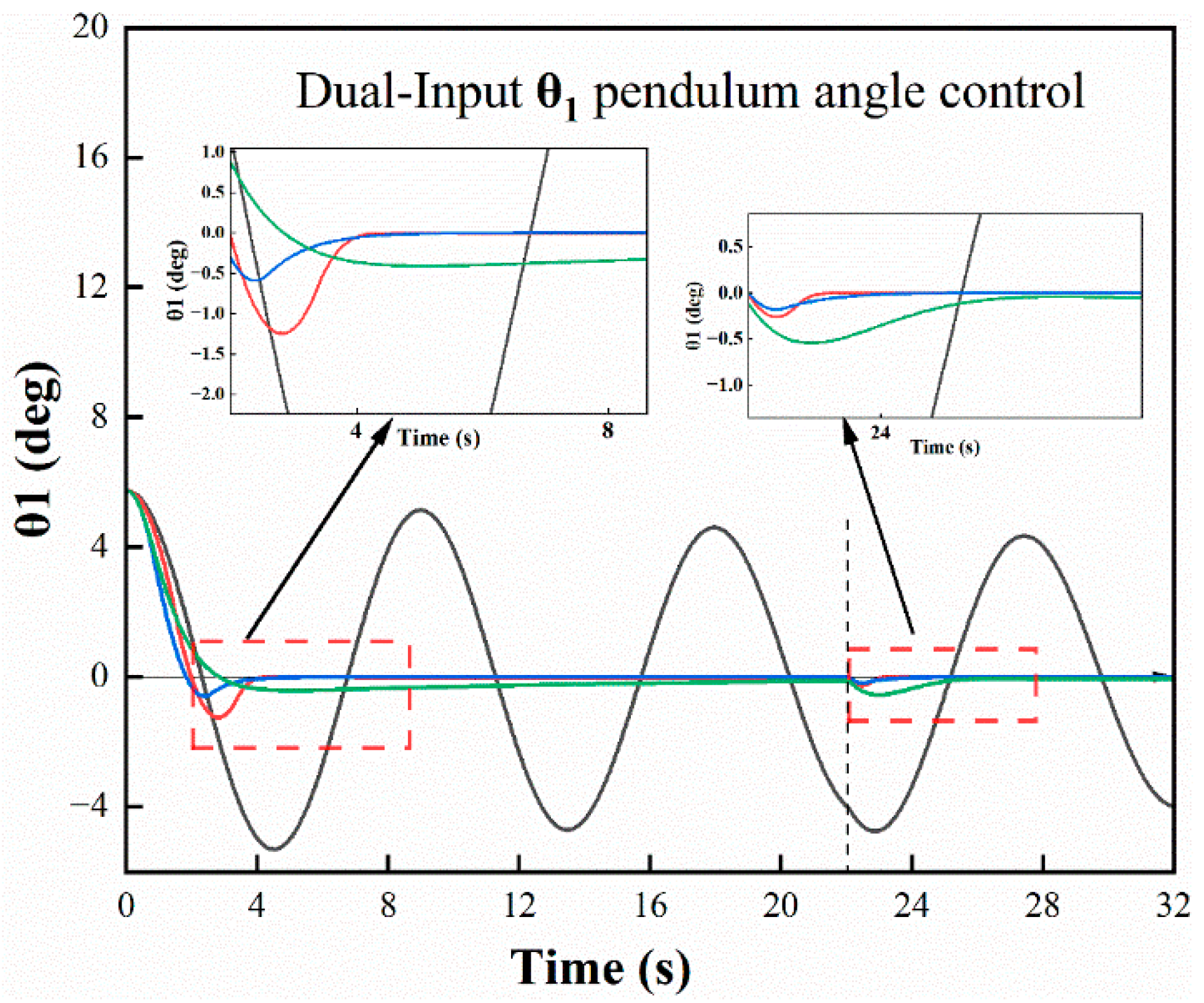

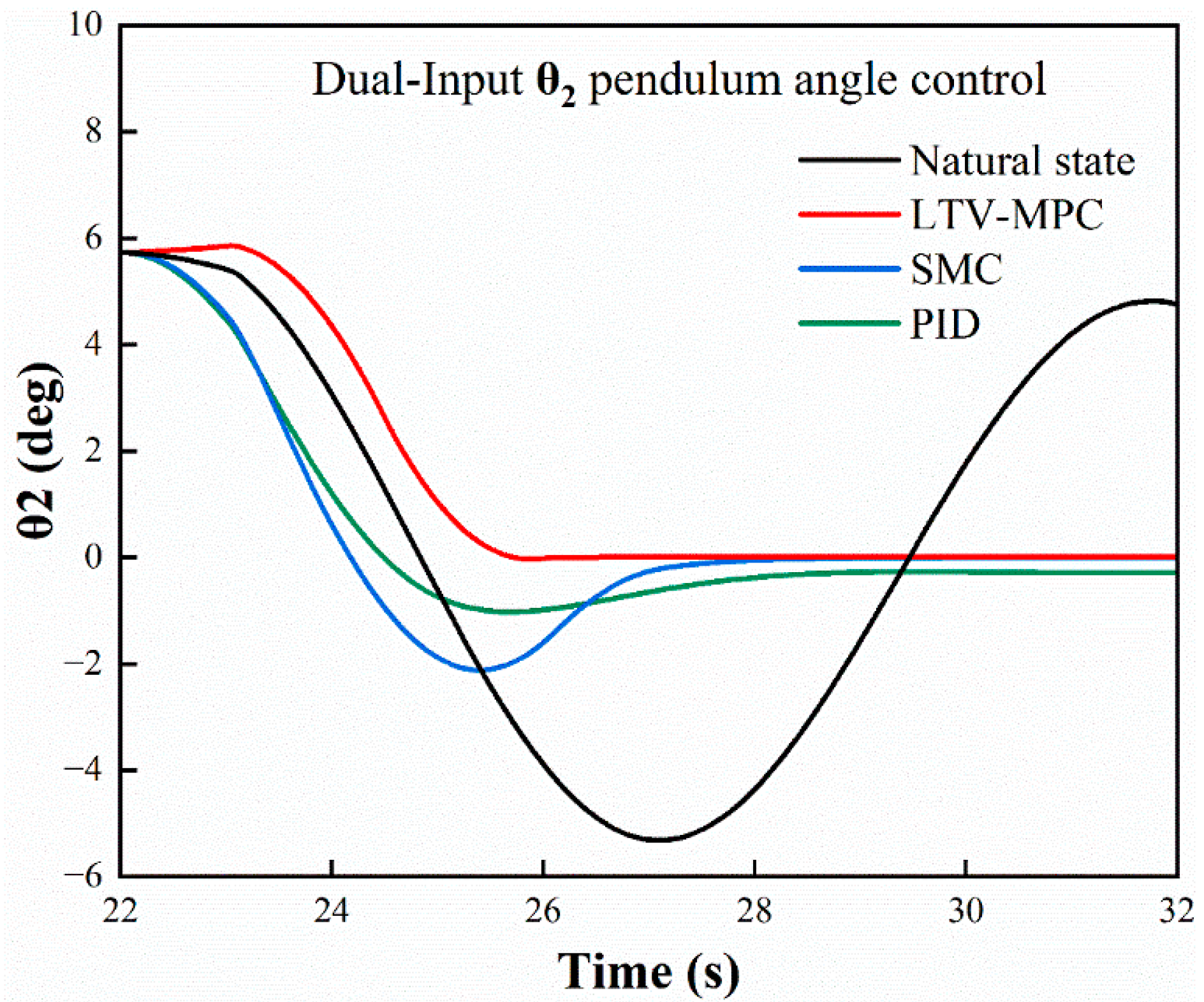

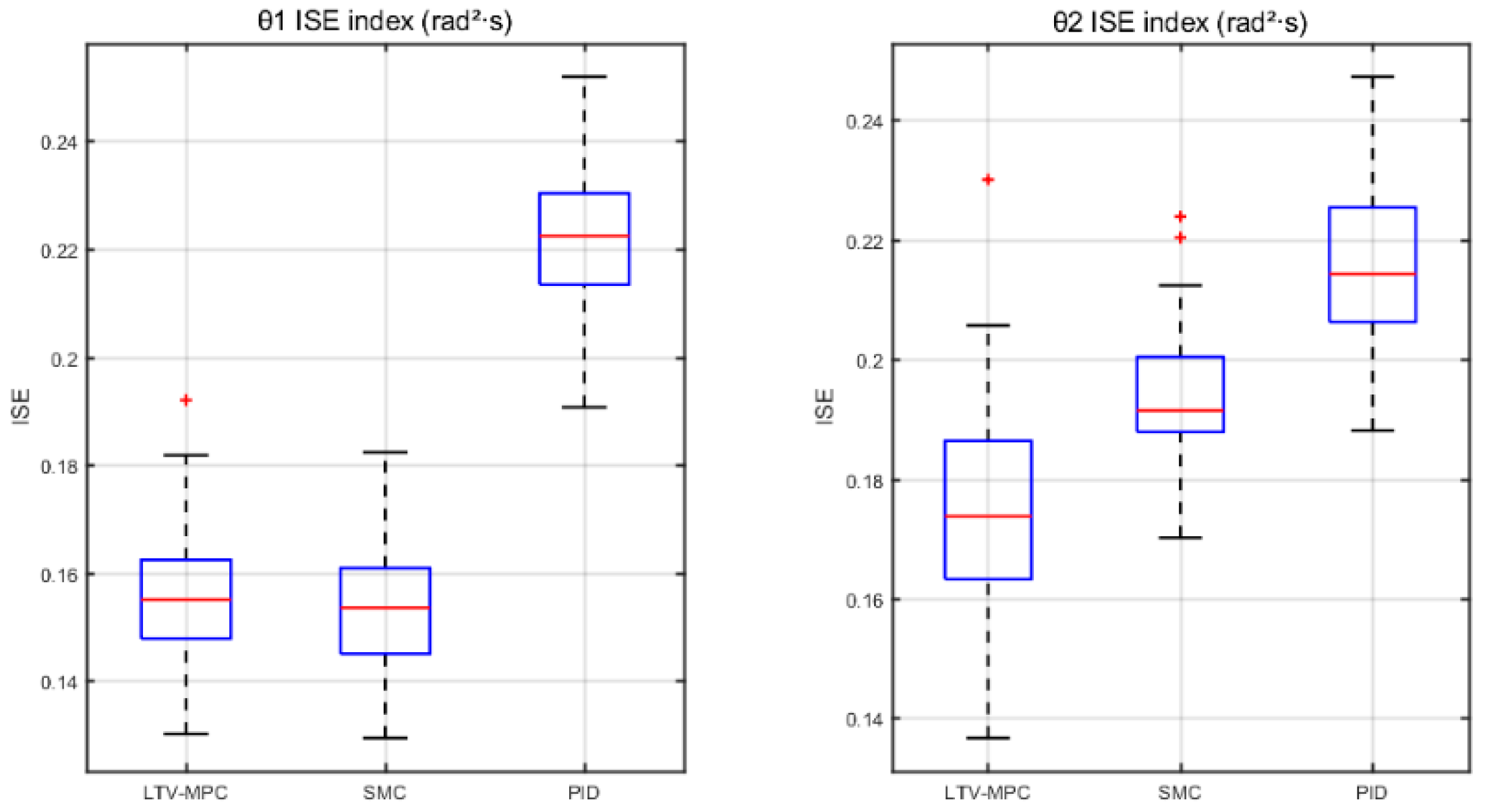

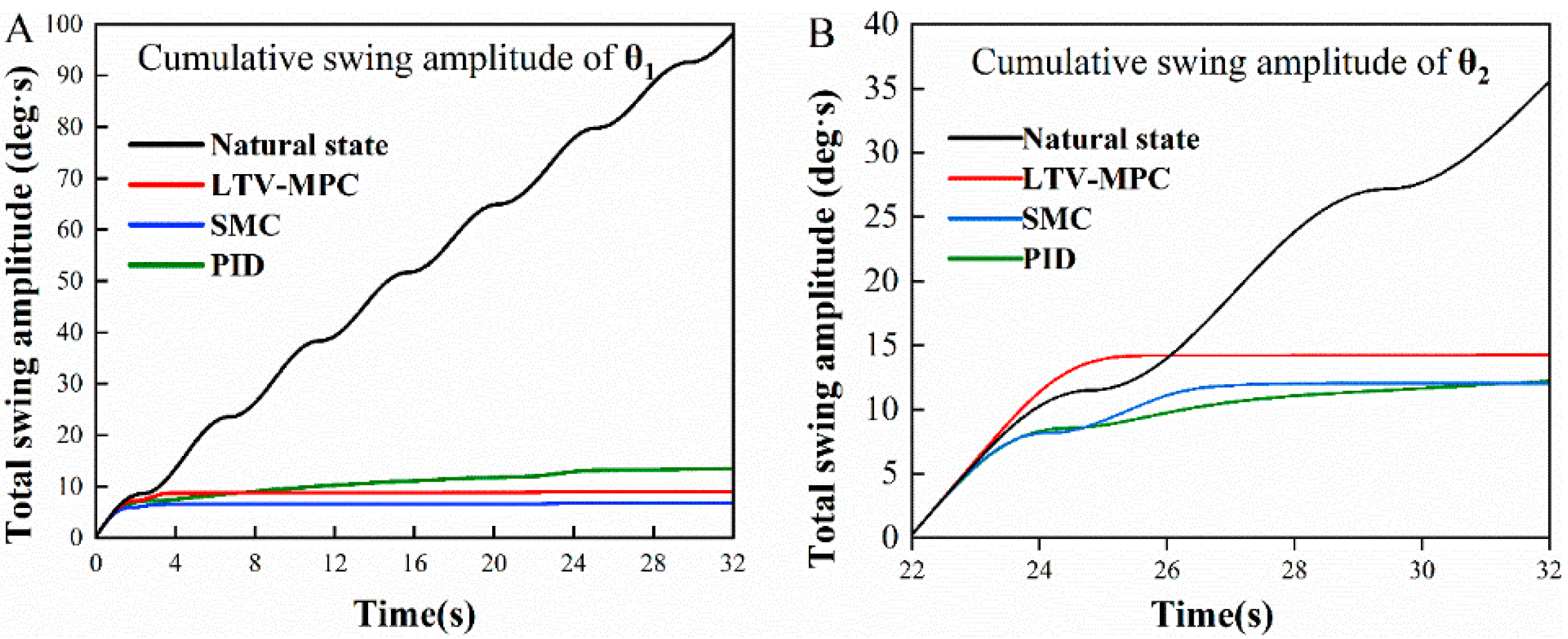

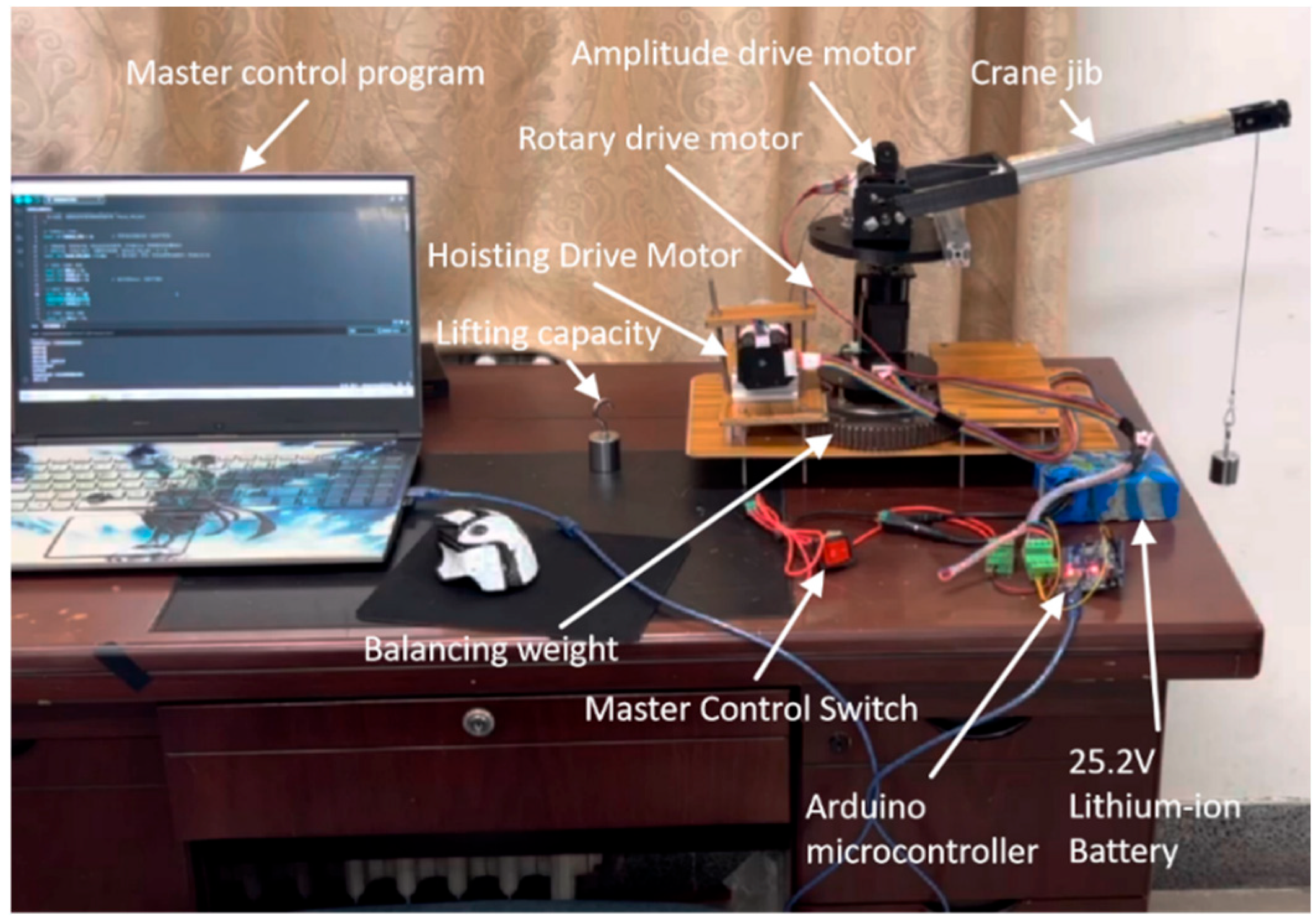

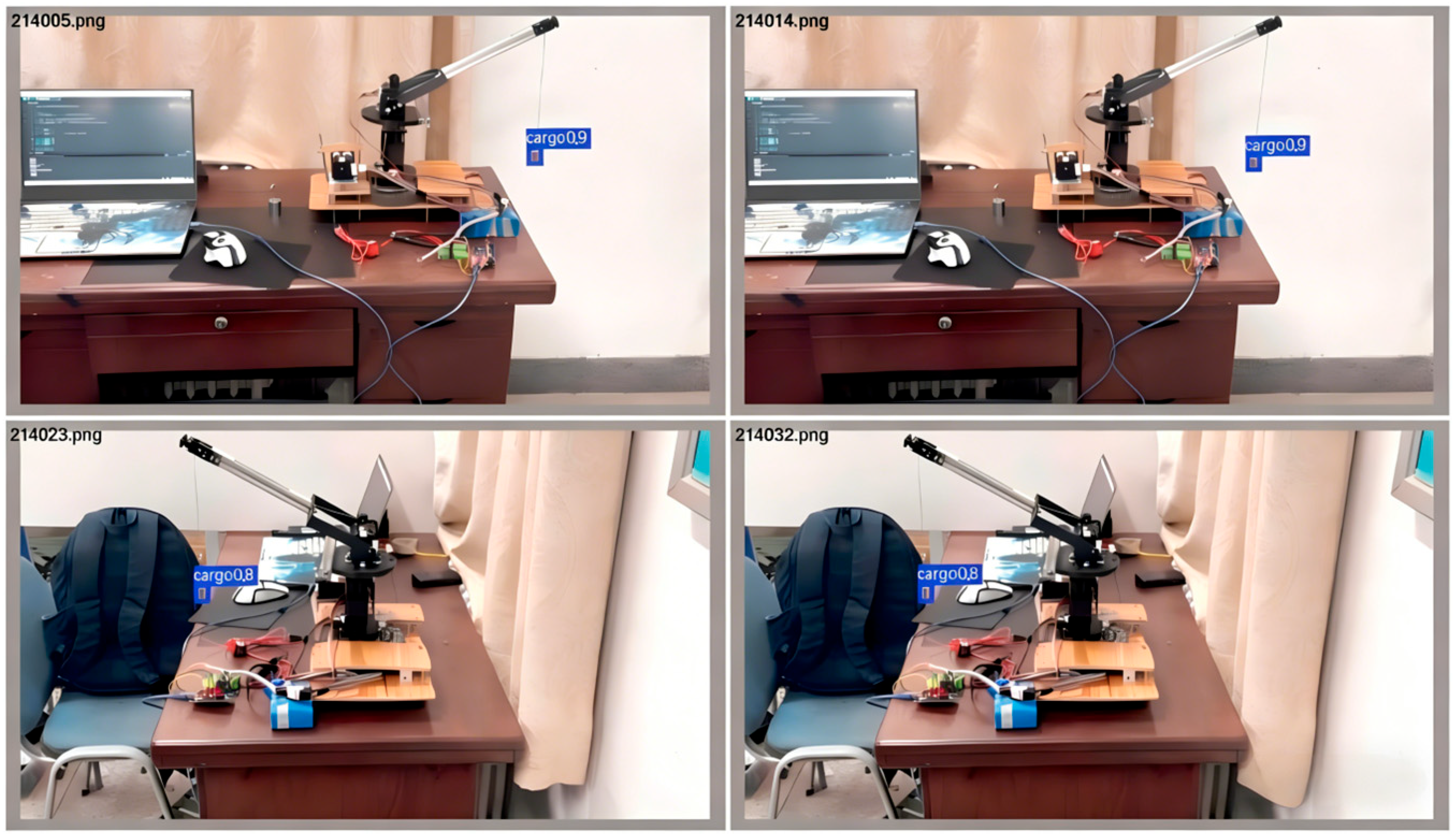

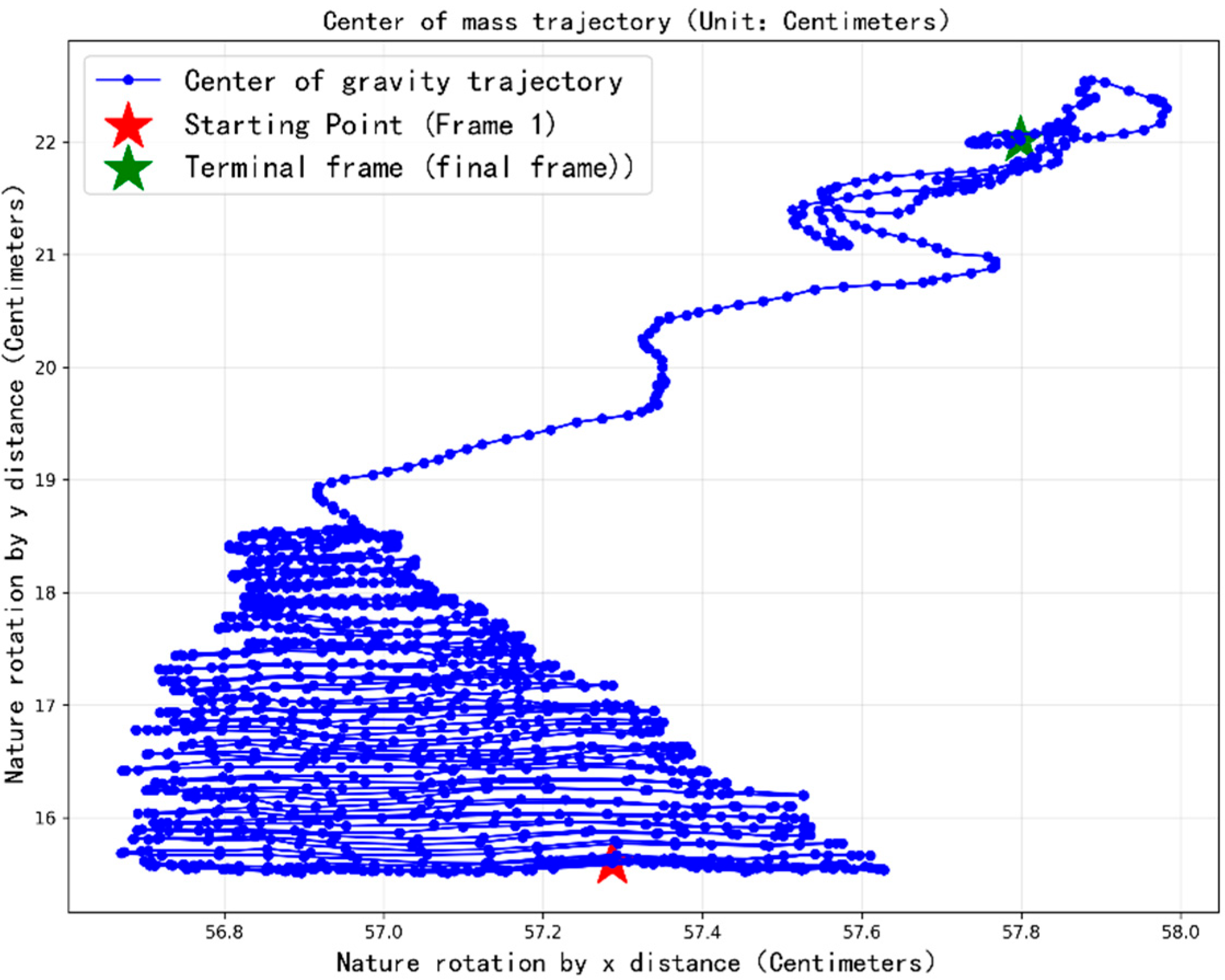

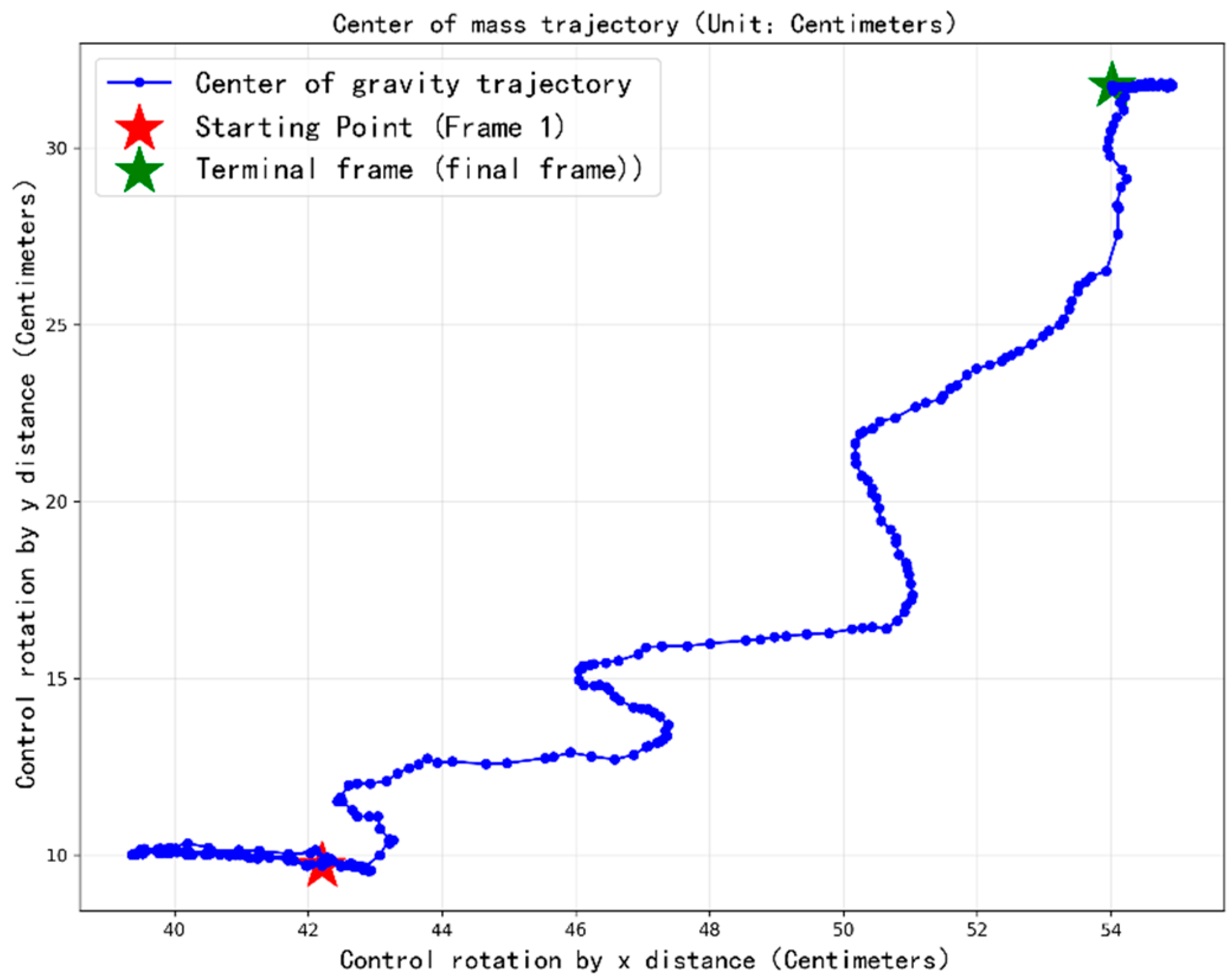

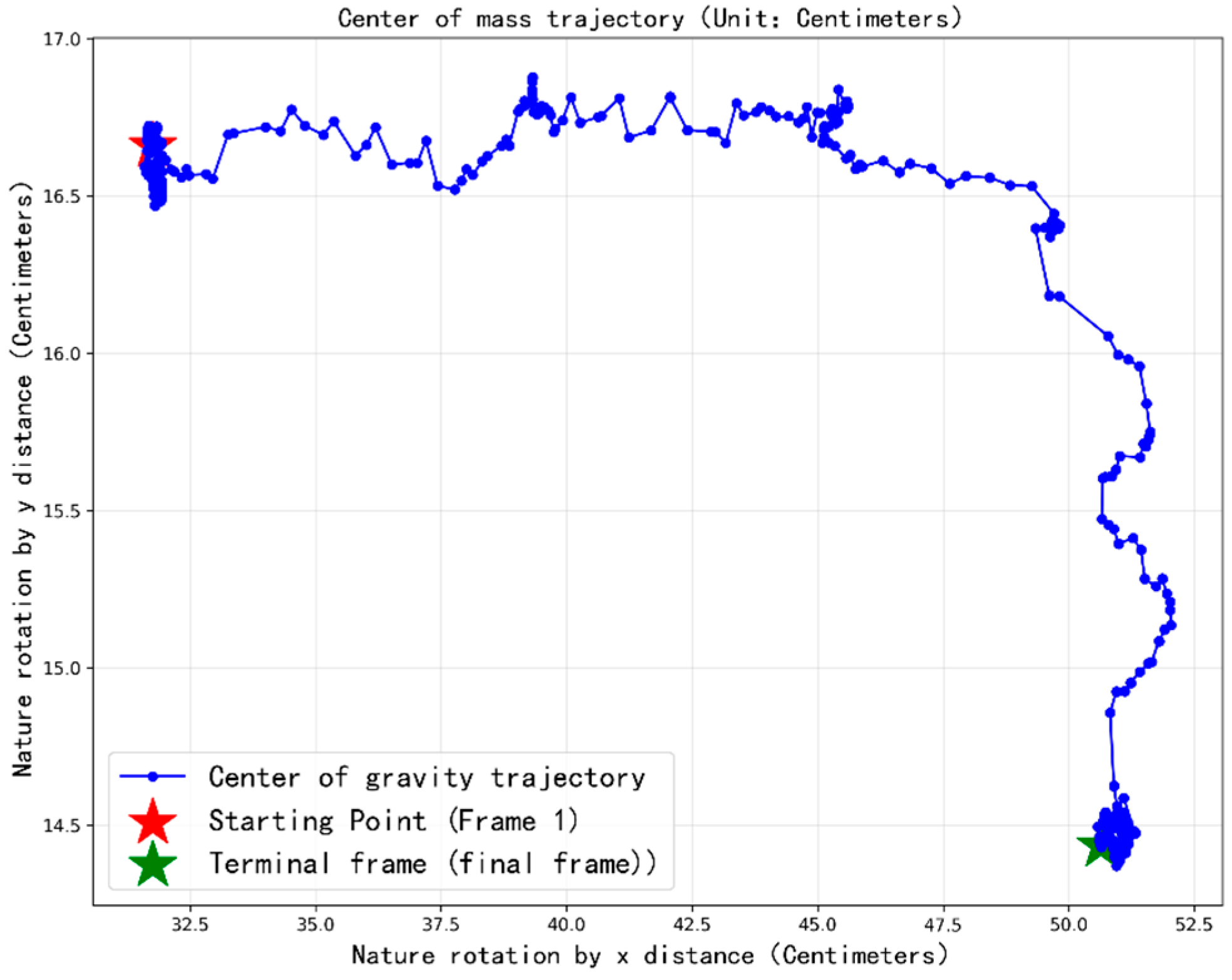

Based on the existing research foundation, this study introduces a modified model predictive control (MPC) strategy by incorporating linear time-varying inputs, referred to as LTV-MPC. This approach is designed for trajectory tracking and swing prediction of the suspended load in an all-terrain crane system. Simulation comparisons were conducted under identical operating conditions against the natural swing state, SMC, and conventional PID control. The results confirm that the proposed LTV-MPC method effectively suppresses payload swing during both luffing and slewing motions.