Reinforcement Learning for Industrial Automation: A Comprehensive Review of Adaptive Control and Decision-Making in Smart Factories

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To review RL research in Industrial Automation, encompassing its algorithms, frameworks, and application domains.

- To identify and categorize the major challenges hindering industrial adoption, including issues of safety, data efficiency, interpretability, and system integration.

- To synthesize emerging strategies and frameworks such as digital twin-assisted RL, hierarchical and modular architectures, safe RL, and transfer learning techniques that address these limitations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Algorithmic Approaches and Comparative Analysis

2.2. Research Dimensions and Synthesis

2.3. Positioning RL Against Classical Control and Optimization Methods

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

((TITLE-ABS-KEY(“reinforcement learning”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“deep reinforcement learning”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“robotics”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“autonomous systems”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“manufacturing automation”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“path planning”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“assembly”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“human-robot collaboration”))) AND PUBYEAR > 2016 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA,”COMP”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA,”ENGI”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA,”MATH”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA,”MATE”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA,”DECI”)) AND (LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE,”ar”) OR LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE,”re”)) AND (LIMIT-TO(SRCTYPE,”j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO(LANGUAGE,”English”))

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion criteria: (i) peer-reviewed journal articles and reviews; (ii) published between 2017 and 2026; (iii) explicitly addressing RL/DRL in robotics, autonomous systems, or manufacturing automation; (iv) containing at least one of the target keywords in title, abstract, or keywords;

- Exclusion criteria: (i) conference proceedings, book chapters, editorials, or non-peer-reviewed sources; (ii) papers outside the scope of Industrial Automation or robotics; (iii) duplicates across databases.

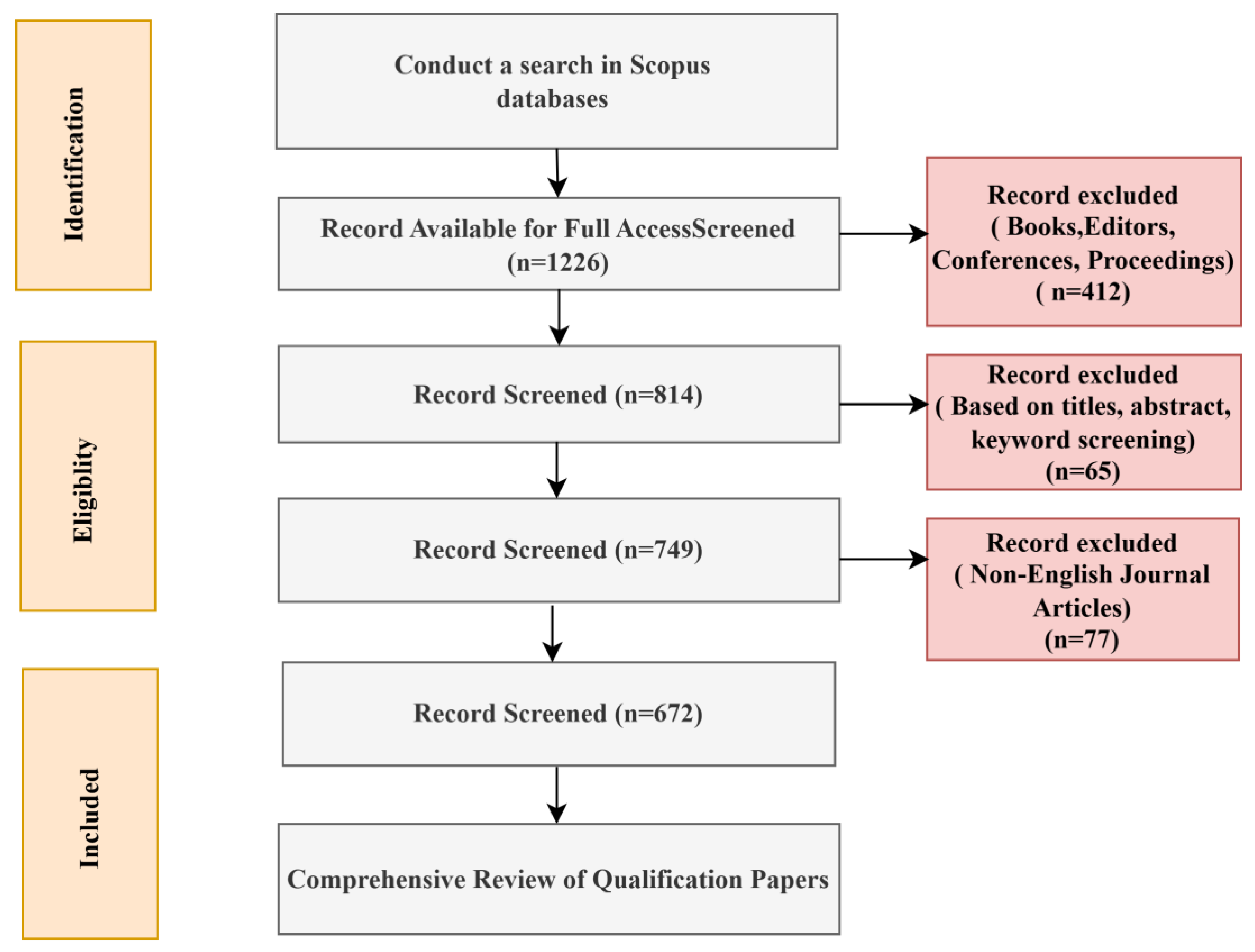

3.3. Selection Process

- Ensuring methodological rigor—all decisions for inclusion/exclusion are systematic rather than arbitrary [61];

- Enhancing transparency—readers can trace the exact filtering path from 1226 initial results to 672 final articles [50];

- Improving reproducibility—future researchers can replicate or extend the review following the same protocol [62].

3.4. Data Extraction and Preparation

3.5. Bibliometric Analysis Tools

3.6. Methodological Quality Assessment

- Clarity of Research Aims: Were the objectives and research questions explicitly defined?

- Methodological Rigor: Was the RL methodology (algorithm, state/action space, reward function) described with sufficient detail for replication?

- Transparency of Results: Were the outcomes, including limitations and deployment challenges, clearly reported?

4. Results and Discussion

- Discrete vs. Continuous Control: Q-Learning excels in low-dimensional, discrete processes, whereas DQN, PPO, and SAC are preferable for high-dimensional, continuous tasks due to their NN-based approximations [8];

- Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Systems: Traditional RL and DQN are suitable for single-agent tasks; MARL is essential when multiple agents must coordinate in a shared environment, such as collaborative robotics or multi-stage production lines [17];

- Safety-Critical Environments: Safe RL and digital twin-integrated approaches are indispensable in contexts where operational failures could have severe financial or safety consequences, offering a balance between exploration and constrained policy execution [36];

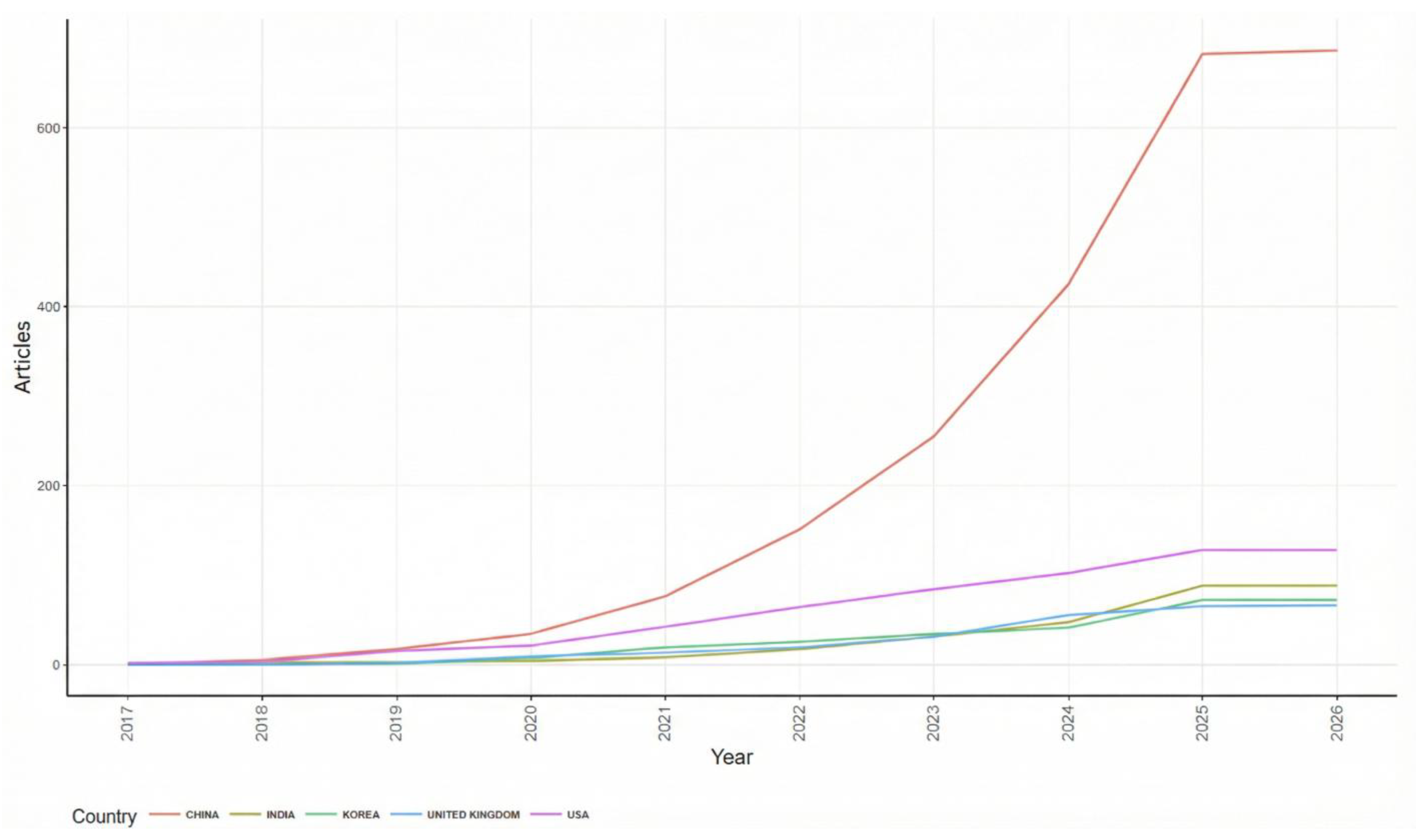

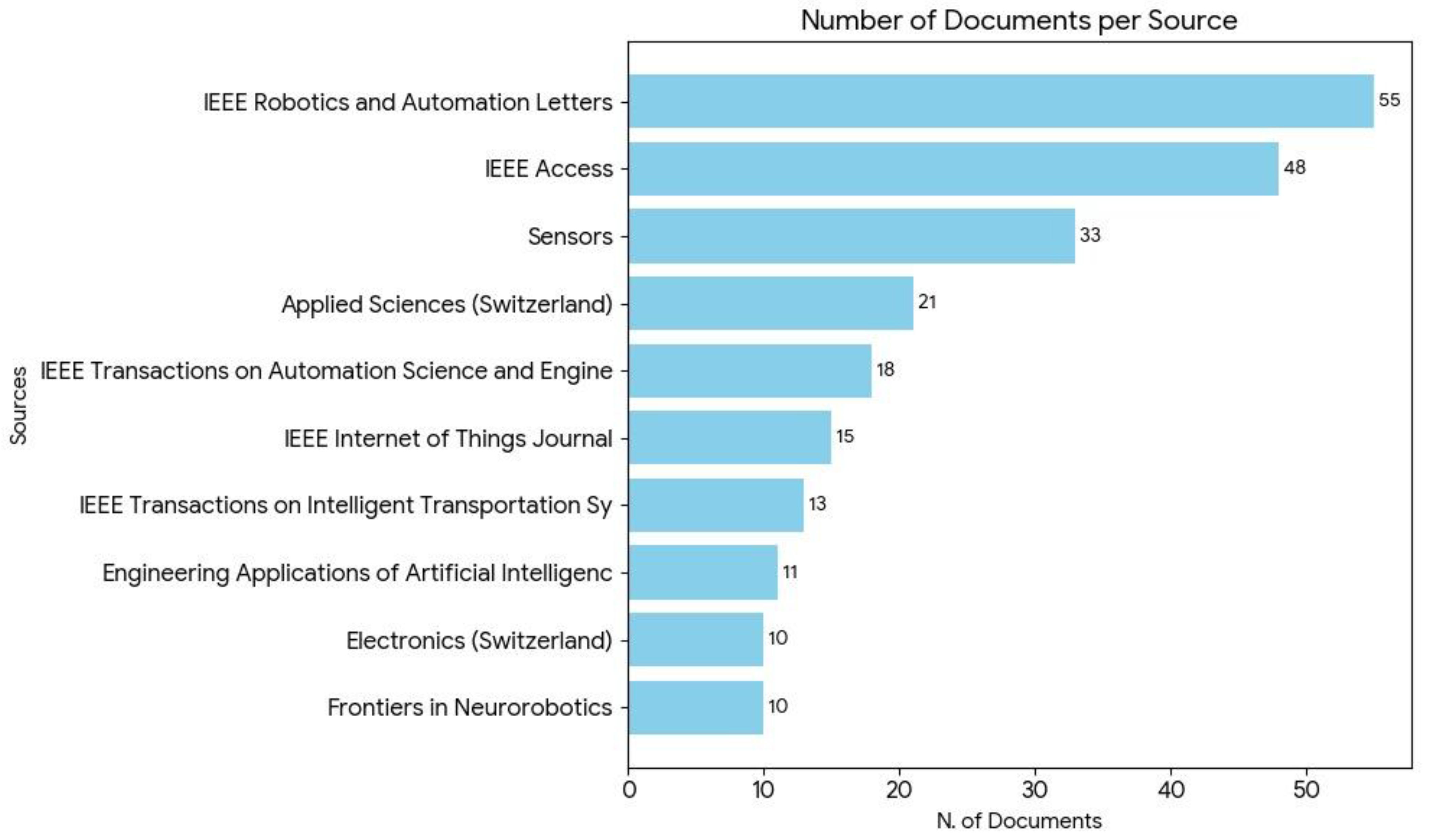

Research Trends and Insights from Bibliometric Analyses

5. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

5.1. Technological Advancements

5.1.1. Digital Twin Integration

5.1.2. Transfer Learning for Industrial Adaptability

5.1.3. Modular and Hierarchical RL Architectures

5.2. Implementation Considerations

5.2.1. Standardization and Interoperability

5.2.2. Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

- Transparency and explainability in RL decision-making processes

- Safety verification protocols for RL systems before and during deployment

- Liability allocation frameworks for autonomous system failures

- Continuous monitoring and update procedures for evolving RL policies

- Human oversight mechanisms ensuring meaningful human control in critical decisions.

5.2.3. Real-World Validation and Scalability

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ASC-RL | Adaptive Scheduling Control using Reinforcement Learning |

| CIoT-DPM | Cognitive IoT–based Dynamic Power Management |

| CPS | cyber-physical systems |

| CTDE | Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| HASAC | Hyper-Actor Soft Actor–Critic |

| HITL-RL | Human-in-the-Loop Reinforcement Learning |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MARL | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| NNs | Neural Networks |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| SAC | Soft Actor–Critic |

| XRL | Explainable Reinforcement learning |

Appendix A

| No. | Study | Clear Research Aims | Detailed Methodology Description | Comprehensive Results Reporting | Appropriate Data Analysis | Relevant Conclusions | Overall Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | De Asis et al. (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [2] | Farooq & Iqbal (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [3] | Xia et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [4] | Ryalat et al. (2023) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [5] | del Real Torres et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [6] | Langås et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [7] | Moos et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [8] | Arulkumaran et al. (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [9] | Han et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [10] | Kober et al. (2013) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [11] | Schulman et al. (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [12] | Hou et al. (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [13] | Sathya et al. (2024) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [14] | Rajasekhar et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [15] | Hady et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [16] | Jia & Pei (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [17] | Abbas et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [18] | Schwung et al. (2018) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | 3/5 |

| [19] | Chang et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [20] | Emami et al. (2024) | ✓ | △ | △ | △ | ✓ | 3/5 |

| [21] | Hernandez-Leal et al. (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [22] | Rolf et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [23] | Martins et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [24] | Xu & Peng (2025) | ✓ | △ | △ | △ | ✓ | 3/5 |

| [25] | Chen et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [26] | Eckardt et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [27] | Paranjape et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [28] | Peta et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [29] | Esteso et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [30] | Khan et al. (2025)—CIoT-DPM | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [31] | Khan et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [32] | Mayer et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [33] | Zhang et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [34] | Phan & Ngo (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [35] | Mohammadi et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [36] | Terven (2025) | ✓ | △ | △ | △ | ✓ | 3/5 |

| [37] | Sola et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [38] | Jin et al. (2025) | ✓ | △ | △ | △ | ✓ | 3/5 |

| [39] | Li (2022) | ✓ | △ | △ | △ | ✓ | 3/5 |

| [40] | Yuan et al. (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [41] | Wang et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [42] | Chen et al. (2024) | ✓ | △ | △ | △ | ✓ | 3/5 |

| [43] | Rahanu et al. (2021) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [44] | Martinho et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [45] | Leikas et al. (2019) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [46] | Hashmi et al. (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [47] | Clark et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [48] | Rădulescu et al. (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [49] | Kallenberg et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [50] | Page et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [51] | Moola et al. (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [52] | Yu et al. (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [53] | Dervis (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [54] | Singh et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [55] | Semeraro et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [56] | Keshvarparast et al. (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [57] | Sizo et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [58] | Marzi et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [59] | Mancin et al. (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [60] | Nezameslami et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [61] | Sarkis-Onofre et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [62] | Moher et al. (2009) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [63] | Samal (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [64] | Ouhadi et al. (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [65] | Aromataris & Pearson (2014) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [66] | Ahn & Kang (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [67] | Liu et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [68] | Khdoudi et al. (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [69] | Wells & Bednarz (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [70] | Su et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [71] | Liu (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [72] | Liengpunsakul (2021) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [73] | Jung & Cho (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [74] | Cheng & Zeng (2023) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [75] | Rajamallaiah et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [76] | Gautam (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [77] | Li et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [78] | Khurram et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [79] | Hagendorff (2021) | ✓ | △ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4/5 |

| [80] | Ilahi et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [81] | Zhang et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [82] | Sun et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [83] | Bouali et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [84] | Noriega et al. (2025) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [85] | Xiao et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [86] | Chen et al. (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [87] | Wei et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [88] | Abo-Khalil (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [89] | Hua et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5/5 |

| [90] | Raziei & Moghaddam (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | △ | ✓ | 4/5 |

- 75.6% of all studies met all quality criteria (68/90 studies)

- 16.7% met 4 out of 5 criteria (15/90 studies)

- 7.8% scored 3 or below (7/90 studies)

- The overall high-quality scores validate the robustness of the literature corpus selected for this systematic review.

References

- Asis, K.D.; Hernandez-Garcia, J.F.; Holland, G.Z.; Sutton, R.S. Multi-step reinforcement learning: A unifying algorithm. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, A.; Iqbal, K. A Survey of Reinforcement Learning for Optimization in Automation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Bari, Italy, 28 August–1 September 2024; pp. 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Sacco, C.; Kirkpatrick, M.; Saidy, C.; Nguyen, L.; Kircaliali, A.; Harik, R. A digital twin to train deep reinforcement learning agent for smart manufacturing plants: Environment, interfaces and intelligence. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryalat, M.; ElMoaqet, H.; AlFaouri, M. Design of a Smart Factory Based on Cyber-Physical Systems and Internet of Things towards Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Real Torres, A.; Andreiana, D.S.; Ojeda Roldán, Á.; Hernández Bustos, A.; Acevedo Galicia, L.E. A Review of Deep Reinforcement Learning Approaches for Smart Manufacturing in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Framework. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langås, E.F.; Zafar, M.H.; Sanfilippo, F. Exploring the synergy of human-robot teaming, digital twins, and machine learning in Industry 5.0: A step towards sustainable manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 89, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, J.; Hansel, K.; Abdulsamad, H.; Stark, S.; Clever, D.; Peters, J. Robust Reinforcement Learning: A Review of Foundations and Recent Advances. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2022, 4, 276–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulkumaran, K.; Deisenroth, M.P.; Brundage, M.; Bharath, A.A. Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Brief Survey. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2017, 34, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Mulyana, B.; Stankovic, V.; Cheng, S. A Survey on Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithms for Robotic Manipulation. Sensors 2023, 23, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, J.; Bagnell, J.A.; Peters, J. Reinforcement learning in robotics: A survey. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1238–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wan, Y.; Li, D.; Fu, C.; Yu, H. Off-policy maximum entropy reinforcement learning: Soft actor-critic with advantage weighted mixture policy (sac-awmp). arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.02829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathya, D.; Saravanan, G.; Thangamani, R. Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Mechatronics Systems. In Computational Intelligent Techniques in Mechatronics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 135–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar, N.; Radhakrishnan, T.K.; Samsudeen, N. Exploring reinforcement learning in process control: A comprehensive survey. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2025, 56, 3528–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hady, M.A.; Hu, S.; Pratama, M.; Cao, Z.; Kowalczyk, R. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for resources allocation optimization: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Pei, Y. Recent Advances in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Intelligent Automation and Control of Water Environment Systems. Machines 2025, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.N.; Amazu, C.W.; Mietkiewicz, J.; Briwa, H.; Perez, A.A.; Baldissone, G.; Demichela, M.; Chasparis, G.C.; Kelleher, J.D.; Leva, M.C. Analyzing Operator States and the Impact of AI-Enhanced Decision Support in Control Rooms: A Human-in-the-Loop Specialized Reinforcement Learning Framework for Intervention Strategies. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 7218–7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwung, D.; Reimann, J.N.; Schwung, A.; Ding, S.X. Self Learning in Flexible Manufacturing Units: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), Madeira, Portugal, 25–27 September 2018; pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Jia, X.; Fu, S.; Hu, H.; Liu, K. Digital twin and deep reinforcement learning enabled real-time scheduling for complex product flexible shop-floor. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 237, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, Y.; Almeida, L.; Li, K.; Ni, W.; Han, Z. Human-in-the-loop machine learning for safe and ethical autonomous vehicles: Principles, challenges, and opportunities. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.12548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Leal, P.; Kartal, B.; Taylor, M.E. A survey and critique of multiagent deep reinforcement learning. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2019, 33, 750–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolf, B.; Jackson, I.; Müller, M.; Lang, S.; Reggelin, T.; Ivanov, D. A review on reinforcement learning algorithms and applications in supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 7151–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.S.E.; Sousa, J.M.C.; Vieira, S. A Systematic Review on Reinforcement Learning for Industrial Combinatorial Optimization Problems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Peng, J. A Comprehensive Survey of Deep Research: Systems, Methodologies, and Applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Qiu, X.; Cai, T.; Dai, H.N.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Internet of Things: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1659–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, J.N.; Wendt, K.; Bornhäuser, M.; Middeke, J.M. Reinforcement Learning for Precision Oncology. Cancers 2021, 13, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjape, A.; Quader, N.; Uhlmann, L.; Berkels, B.; Wolfschläger, D.; Schmitt, R.H.; Bergs, T. Reinforcement Learning Agent for Multi-Objective Online Process Parameter Optimization of Manufacturing Processes. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peta, K.; Wiśniewski, M.; Kotarski, M.; Ciszak, O. Comparison of Single-Arm and Dual-Arm Collaborative Robots in Precision Assembly. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteso, A.; Peidro, D.; Mula, J.; Díaz-Madroñero, M. Reinforcement learning applied to production planning and control. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 5772–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Ullah, I.; Bashir, A.K.; Al-Khasawneh, M.A.; Arishi, A.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Lee, S. Reinforcement Learning-Based Dynamic Power Management for Energy Optimization in IoT-Enabled Consumer Electronics. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 8103–8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Lee, S.; Shah, M. Adaptive Scheduling in Cognitive IoT Sensors for Optimizing Network Performance Using Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.A.D.; Ngo, H.Q.T. Systematic Review of Smart Robotic Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0. In Context-Aware Systems and Applications, Proceedings of the 12th EAI International Conference, ICCASA 2023, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 26–27 October 2023; Vinh, P.C., Tung, N.T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; Classen, T.; Endisch, C. Modular production control using deep reinforcement learning: Proximal policy optimization. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 2335–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Amaitik, N.; Xu, Y. Dynamic Scheduling Method for Job-Shop Manufacturing Systems by Deep Reinforcement Learning with Proximal Policy Optimization. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Ortiz-Arroyo, D.; Hansen, A.A.; Stokholm-Bjerregaard, M.; Gros, S.; Anand, A.S.; Durdevic, P. Application of Soft Actor-Critic algorithms in optimizing wastewater treatment with time delays integration. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 277, 127180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J. Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Chronological Overview and Methods. AI 2025, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, Y.; Le Chenadec, G.; Clement, B. Simultaneous Control and Guidance of an AUV Based on Soft Actor–Critic. Sensors 2022, 22, 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Du, H.; Zhao, B.; Tian, X.; Shi, B.; Yang, G. A comprehensive survey on multi-agent cooperative decision-making: Scenarios, approaches, challenges and perspectives. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Reinforcement learning in practice: Opportunities and challenges. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.11296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, M.; Ban, X. Controlling Partially Observed Industrial System Based on Offline Reinforcement Learning—A Case Study of Paste Thickener. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ruan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Control strategy of robotic manipulator based on multi-task reinforcement learning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, J.; Chen, F.; Lv, Z.; Tang, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.H.; Han, G. Towards General Industrial Intelligence: A Survey of Continual Large Models in Industrial IoT. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.01207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahanu, H.; Georgiadou, E.; Siakas, K.; Ross, M.; Berki, E. Ethical Issues Invoked by Industry 4.0. In Systems, Software and Services Process Improvement, Proceedings of the 28th European Conference, EuroSPI 2021, Krems, Austria, 1–3 September 2021; Yilmaz, M., Clarke, P., Messnarz, R., Reiner, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, A.; Herber, N.; Kroesen, M.; Chorus, C. Ethical issues in focus by the autonomous vehicles industry. Transp. Rev. 2021, 41, 556–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leikas, J.; Koivisto, R.; Gotcheva, N. Ethical Framework for Designing Autonomous Intelligent Systems. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, R.; Liu, H.; Yavari, A. Digital Twins for Enhancing Efficiency and Assuring Safety in Renewable Energy Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2024, 17, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.; Garcia, B.; Harris, S. Digital Twin-Driven Operational Management Framework for Real-Time Decision-Making in Smart Factories. J. Innov. Gov. Bus. Pract. 2025, 1, 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rădulescu, R.; Mannion, P.; Roijers, D.M.; Nowé, A. Multi-objective multi-agent decision making: A utility-based analysis and survey. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2019, 34, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallenberg, M.; Baja, H.; Ilić, M.; Tomčić, A.; Tošić, M.; Athanasiadis, I. Interoperable agricultural digital twins with reinforcement learning intelligence. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Tufanaru, C.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Mu, P. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute’s approach. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X. Bibliometric analysis of support vector machines research trend: A case study in China. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2020, 11, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derviş, H. Bibliometric analysis using bibliometrix an R package. J. Scientometr. Res. 2019, 8, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, F.; Griffiths, A.; Cangelosi, A. Human–robot collaboration and machine learning: A systematic review of recent research. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 79, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshvarparast, A.; Battini, D.; Battaia, O.; Pirayesh, A. Collaborative robots in manufacturing and assembly systems: Literature review and future research agenda. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 2065–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizo, A.; Lino, A.; Rocha, Á.; Reis, L.P. Defining quality in peer review reports: A scoping review. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 6413–6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G.; Balzano, M.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M.M. Guidelines for Bibliometric-Systematic Literature Reviews: 10 steps to combine analysis, synthesis and theory development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2025, 27, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Andreoli, D.; Soekeland, F.; Anastasi, G.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.G. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews: A method for conducting comprehensive analysis. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezameslami, R.; Nezameslami, A.; Mehdikhani, B.; Mosavi-Jarrahi, A.; Shahbazi, A.; Rahmani, A.; Masoudi, A.; Yeganegi, M.; Akhondzardaini, R.; Bahrami, M.; et al. Adapting PRISMA Guidelines to Enhance Reporting Quality in Genetic Association Studies: A Framework Proposal. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2025, 26, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Catalá-López, F.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The, P.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, U. Evolution of machine learning and deep learning in intelligent manufacturing: A bibliometric study. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2025, 16, 3134–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhadi, A.; Yahouni, Z.; Di Mascolo, M. Integrating machine learning and operations research methods for scheduling problems: A bibliometric analysis and literature review. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Pearson, A. The Systematic Review: An Overview. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, E.; Kang, H. Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J. Anesth. 2018, 71, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, D.; Wang, L. A digital twin-based sim-to-real transfer for deep reinforcement learning-enabled industrial robot grasping. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2022, 78, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khdoudi, A.; Masrour, T.; El Hassani, I.; El Mazgualdi, C. A Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based Digital Twin for Manufacturing Process Optimization. Systems 2024, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, L.; Bednarz, T. Explainable AI and Reinforcement Learning—A Systematic Review of Current Approaches and Trends. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 550030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; Wu, T.; Zhao, J.; Scaglione, A.; Xie, L. A Review of Safe Reinforcement Learning Methods for Modern Power Systems. Proc. IEEE 2025, 113, 213–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Bridging research and policy in China’s energy sector: A semantic and reinforcement learning framework. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 59, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liengpunsakul, S. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development in China. Chin. Econ. 2021, 54, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Cho, K. Deep Learning and NLP-Based Trend Analysis in Actuators and Power Electronics. Actuators 2025, 14, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zeng, J. Shaping AI’s Future? China in Global AI Governance. J. Contemp. China 2023, 32, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamallaiah, A.; Naresh, S.V.K.; Raghuvamsi, Y.; Manmadharao, S.; Bingi, K.; Anand, R.; Guerrero, J.M. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Power Converter Control: A Comprehensive Review of Applications and Challenges. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2025, 6, 1769–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Resilient Power and Energy Systems: Progress, Prospects, and Future Avenues. Electricity 2023, 4, 336–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bai, L.; Yao, L.; Waller, S.T.; Liu, W. A bibliometric analysis and review on reinforcement learning for transportation applications. Transp. B Transp. Dyn. 2023, 11, 2179461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurram, M.; Zhang, C.; Muhammad, S.; Kishnani, H.; An, K.; Abeywardena, K.; Chadha, U.; Behdinan, K. Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing Industry Worker Safety: A New Paradigm for Hazard Prevention and Mitigation. Processes 2025, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagendorff, T. Forbidden knowledge in machine learning reflections on the limits of research and publication. AI Soc. 2021, 36, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilahi, I.; Usama, M.; Qadir, J.; Janjua, M.U.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Hoang, D.T.; Niyato, D. Challenges and Countermeasures for Adversarial Attacks on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, X.; Tang, L.; Yin, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Application of machine learning, deep learning and optimization algorithms in geoengineering and geoscience: Comprehensive review and future challenge. Gondwana Res. 2022, 109, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, W.; Yu, R.; Zhang, Y. Motion Planning for Mobile Robots—Focusing on Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 69061–69081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouali, M.; Sebaa, A.; Farhi, N. A Comprehensive Review on Reinforcement Learning Methods for Autonomous Lane Changing. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, R.; Pourrahimian, Y.; Askari-Nasab, H. Deep Reinforcement Learning based real-time open-pit mining truck dispatching system. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 173, 106815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liu, B.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. Motion planning and control for mobile robot navigation using machine learning: A survey. Auton. Robot. 2022, 46, 569–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, C.; Peng, D.; Ge, H. Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machinery: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 224985–225003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, H.; Tao, X.; Pan, K.; Huang, R.; Ji, W.; Wang, J. Insights into the Application of Machine Learning in Industrial Risk Assessment: A Bibliometric Mapping Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Khalil, A.G. Digital twin real-time hybrid simulation platform for power system stability. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 49, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Zeng, L.; Li, G.; Ju, Z. Learning for a Robot: Deep Reinforcement Learning, Imitation Learning, Transfer Learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziei, Z.; Moghaddam, M. Enabling adaptable Industry 4.0 automation with a modular deep reinforcement learning framework. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RL Model/Approach | Industrial Application | Key Advantages | Key Challenges | Representative Studies | Real-World Deployment Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-Learning | Adaptive process control, simple robotic tasks | Easy to implement; effective in discrete action spaces | Limited scalability; poor performance in high-dimensional continuous spaces | [2,8] | Mostly simulation and lab-scale deployment; limited industrial adoption |

| Collaborative Robotics (Single- vs. Dual-Arm RL-Assisted Control) | Precision assembly, dual-arm and single-arm robot evaluation, production station design | Improves assembly speed and path efficiency; dual-arm faster (20%); supports energy/performance trade-off analysis; simulation-driven optimization | Energy-speed trade-offs; requires high-fidelity simulation; profitability varies by task complexity | [28] | Simulation-based evaluation; applicable to industrial workstation design and robot deployment planning |

| Deep Q-Networks (DQN) | Robotic automation, assembly, pick-and-place | Handles high-dimensional sensory inputs; scalable to complex tasks | Requires large datasets; computationally intensive | [9,10,32] | Some pilot-scale deployments; emerging industrial adoption in robotics |

| Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | Supply chain management, production scheduling | Stable learning; effective for continuous action spaces; robust to hyperparameter changes | Sensitive to environment variability; may require extensive tuning | [11,33,34] | Primarily simulation; limited real-world application in dynamic supply chains |

| Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) | Energy-efficient process control, continuous robotics tasks | Sample-efficient; handles continuous actions; robust exploration | Complex implementation; sensitive to hyperparameter tuning | [35,36,37] | Mostly lab-scale; experimental deployments in process control and robotics |

| MARL | Multi-robot coordination, collaborative production | Decentralized decision-making; scalable for multi-agent environments | Communication overhead; coordination complexity; convergence issues | [1,15,38] | Early-stage pilot tests; limited industrial adoption |

| Offline/Batch RL | Processes with limited real-time data | Learns from historical datasets; safer for industrial deployment | Poor adaptability to unobserved states; performance depends on dataset quality | [2,39,40] | Some real-world trials in chemical and manufacturing processes |

| Hierarchical/Modular RL | Complex industrial systems with multiple sub-tasks | Enables task decomposition; improves scalability and transfer learning | Requires careful task structuring; may increase computational complexity | [41,42] | Mostly experimental and simulation-based; few industrial pilots |

| Constrained/Safe RL | Safety-critical industrial processes | Incorporates safety constraints; reduces risk of operational failures | Can limit exploration and performance; complex constraint design | [43,44,45] | Limited industrial deployment in high-risk manufacturing |

| Digital Twin-Integrated RL | Real-time optimization and predictive maintenance | Allows virtual simulation before deployment; reduces risk; enhances safety | Requires accurate digital twin models; high computational demand | [46,47] | Pilot projects in manufacturing, energy, and logistics; increasing adoption |

| IoT-Optimized RL | Energy management, sensor networks, consumer electronics | Reduces network congestion, improves energy efficiency, handles redundant data patterns | Limited to specific IoT architectures, requires sensor state management | [30,31] | Early industrial adoption in consumer electronics; emerging in industrial IoT |

| Aspect | Description/Coverage | Representative Studies | Key Insights/Contributions | Identified Gaps & Future Research Needs | Key Trends & Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Focus | Application of RL for adaptive control and intelligent decision-making in smart manufacturing environments | [2,6,9] | RL enables autonomous optimization of processes, robotics, and supply chain systems through continuous learning | Limited real-world deployment and integration with legacy automation systems | Shift from classical RL to multi-agent and hierarchical RL for complex systems |

| Core RL Algorithms | Q-Learning, DQN, PPO, SAC, MARL, Offline RL, Hierarchical RL, Safe RL, Digital Twin–Integrated RL | [1,6,9,10,11,13,14,27,29] | Progressive evolution from discrete control to continuous, multi-agent, and simulation-driven control | Sample inefficiency, hyperparameter tuning, and limited interpretability | Emergence of safe, explainable, and hybrid RL methods |

| Industrial Application Areas | Process control, robotic automation, logistics and supply chain, energy management, predictive maintenance | [9,24,25,28,29,30,31] | RL improves precision, adaptability, and energy efficiency across domains | Underexplored applications in energy management and large-scale coordination | Growing focus on sustainable, energy-efficient, and smart manufacturing |

| Integration Technologies | CPS, IoT, Digital Twins, Edge AI, Cloud-based RL frameworks | [3,4,16,30,40,41] | Enhances simulation-based optimization, safety, and real-time decision-making | High computational cost and need for real-time synchronization between physical and virtual layers | Digital twins and CPS integration facilitate sim-to-real transfer and pilot deployments |

| Advantages of RL in Automation | Adaptive decision-making, real-time optimization, autonomous control, self-learning, reduced programming effort | [2,8,25,30,31] | Significant improvement in operational flexibility and fault tolerance | Scalability and explainability remain key constraints | Supports modular, flexible, and self-optimizing production processes |

| Major Challenges | Sample inefficiency, safety and robustness, interpretability, integration with legacy systems | [6,18,34] | Recognized barriers to industrial deployment | Need for hybrid RL methods combining model-based, safe, and explainable learning | Safety, trust, and interpretability are critical bottlenecks |

| Emerging Strategies | Digital Twin–Integrated RL, Hierarchical and Modular RL, Safe and XRL, Transfer Learning | [16,17,35,36,40] | Improve scalability, safety, and transferability | Lack of standardized evaluation frameworks and benchmarks | Hybrid, modular, and transfer learning approaches are accelerating real-world adoption |

| Validation and Deployment | Predominantly simulation or pilot-scale; limited industrial field tests | [9,14,33,41] | Promising pilot results in robotics and predictive maintenance | Require large-scale case studies and longitudinal validation | Simulation remains primary testing environment; limited full-scale deployment |

| Ethical and Regulatory Aspects | Safety compliance, human–AI collaboration, decision transparency, accountability | [18,37,42,43] | Growing attention to AI ethics and trust | Need for policy-aligned frameworks for safe AI integration | Explainable and safe RL is essential for human–AI collaboration and regulatory compliance |

| Future Research Directions | Hybrid RL frameworks, digital twin co-simulation, data-efficient learning, explainable and safe RL for Industry 5.0 | [19,20,21,30,31,40,43] | Pathway toward self-optimizing, human-centered, and sustainable smart factories | Bridging theoretical RL advances with industrial-scale implementation | Standardized benchmarks, data-efficient methods, and human-centered designs are needed for widespread adoption |

| RL Category | Representative Algorithms | Typical Applications | Integration Technologies | Advantages | Limitations | Deployment Status | Key Trends & Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical RL | Q-Learning | Discrete control tasks, simple process automation | None/basic simulation | Simple, low computational cost | Poor scalability, limited to low-dimensional problems | Simulation/pilot-scale | Still foundational for benchmarking; used for small-scale, low-risk tasks |

| DRL | DQN, PPO, SAC | High-dimensional robotic tasks, pick-and-place, assembly, process control, adaptive IoT sensor scheduling, collaborative assembly analysis | Digital Twins, IoT, CPS | Handles high-dimensional inputs, continuous actions; robust and stable | Sample inefficiency, black-box nature | Pilot-scale/industrial experiments | Core of DRL-driven automation; increasing use in multi-stage industrial systems |

| MARL | MADDPG, QMIX | Collaborative robotics, decentralized production lines, dual-arm cooperative assembly | CPS, IoT, networked environments dual-arm cooperative assembly | Supports coordination among multiple agents; scalable for distributed systems | Coordination complexity, communication overhead | Pilot-scale/research testbeds | Essential for multi-agent and distributed industrial applications |

| Hierarchical & Modular RL | Options framework, Feudal RL | Multi-stage production, task decomposition | Digital Twins, IoT | Knowledge transfer, improved learning efficiency, interpretable | Complex design, integration overhead | Pilot-scale | Emerging for scalability, modularity, and energy efficiency |

| Safe & XRL | Constrained RL, XRL | Safety-critical processes, predictive maintenance | Digital Twins, CPS | Ensures operational compliance, builds trust, improves reliability | Slower learning, limited generalization | Pilot-scale/small deployment | Key for regulatory compliance and human-centered design |

| Hybrid RL | Model-based + model-free approaches | Adaptive control, optimization under uncertainty, IoT power Management | Digital Twins, CPS, IoT | Combines sample efficiency with robustness; reduces sim-to-real gap | Design complexity, computational cost | Simulation/early industrial deployment | Trend toward bridging theory and practical deployment; supports Industry 5.0 objectives |

| Aspect | Classical Control (PID/MPC) | Optimization Algorithms | Reinforcement Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Requirements | Requires accurate system models (MPC) or transfer functions | Model-free or model-based variants | Model-free; learns from interaction |

| Adaptability | Limited; requires retuning for new conditions | Good for static optimization | High adaptability to dynamic environments |

| Handling Uncertainty | Limited performance under high uncertainty | Variable performance | Excels in stochastic, nonlinear environments |

| Sample Efficiency | High-minimal data for tuning | Medium-high | Very low-millions of interactions needed |

| Safety & Reliability | Proven stability guarantees | Depends on implementation | Safety concerns during exploration |

| Interpretability | Transparent and interpretable | Medium interpretability | Black-box nature limits trust |

| Computational Demand | Low to medium | Medium to high | High computational intensity |

| Integration Complexity | Mature integration with legacy systems | Moderate | Challenging integration with existing infrastructure |

| Real-world Deployment | Extensive industrial deployment | Widespread use | Limited to pilot-scale (22% of studies) |

| Best Suited For | Well-defined, deterministic processes | Static optimization problems | Complex, dynamic environments with simulation capability |

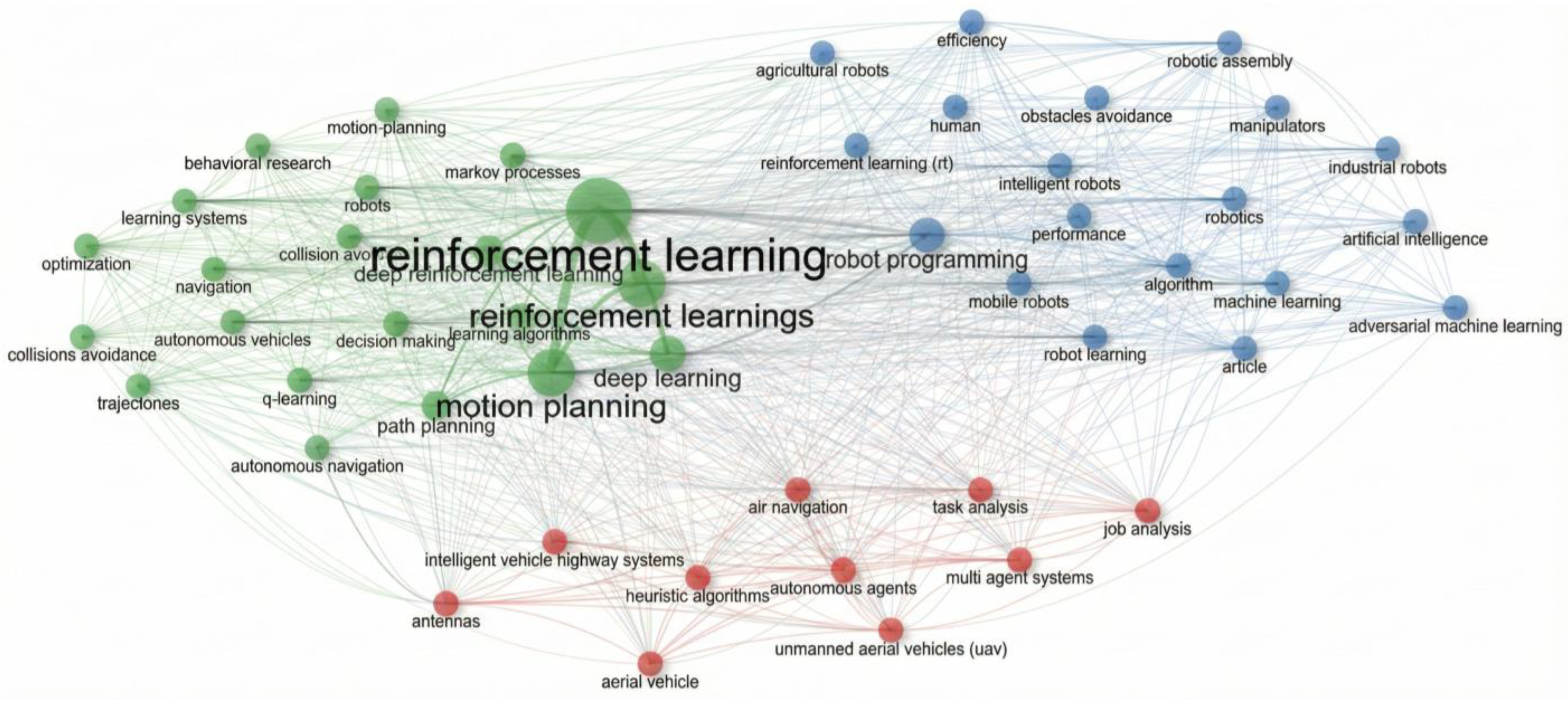

| NO. | Terms | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | reinforcement learning | 594 | 14.00613063 |

| 2 | reinforcement learnings | 358 | 8.441405329 |

| 3 | motion planning | 339 | 7.993397784 |

| 4 | deep learning | 233 | 5.493987267 |

| 5 | robot programming | 219 | 5.163876444 |

| 6 | deep reinforcement learning | 205 | 4.833765621 |

| 7 | path planning | 179 | 4.220702664 |

| 8 | learning algorithms | 119 | 2.805941995 |

| 9 | robotics | 105 | 2.475831172 |

| 10 | learning systems | 95 | 2.240037727 |

| … | |||

| 47 | collisions avoidance | 28 | 0.660221646 |

| 48 | manipulators | 27 | 0.636642301 |

| 49 | performance | 27 | 0.636642301 |

| 50 | reinforcement learning (RL) | 27 | 0.636642301 |

| Term | Frequency | Year (Q1) | Year (Median) | Year (Q3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reinforcement learning | 593 | 2022 | 2024 | 2025 |

| reinforcement learnings | 358 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

| motion planning | 339 | 2022 | 2024 | 2025 |

| learning algorithms | 119 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| learning systems | 95 | 2021 | 2023 | 2024 |

| robot learning | 87 | 2024 | 2025 | 2025 |

| machine learning | 72 | 2020 | 2023 | 2024 |

| robots | 56 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| robotics | 105 | 2021 | 2022 | 2024 |

| adversarial machine learning | 35 | 2024 | 2025 | 2025 |

| markov processes | 30 | 2020 | 2022 | 2024 |

| agricultural robots | 29 | 2020 | 2021 | 2023 |

| reinforcement learning method | 26 | 2020 | 2022 | 2025 |

| multipurpose robots | 26 | 2024 | 2025 | 2025 |

| reinforcement learning approach | 17 | 2021 | 2021 | 2023 |

| markov decision processes | 14 | 2019 | 2020 | 2024 |

| deep learning in robotics and automation | 8 | 2019 | 2020 | 2020 |

| path planning problems | 8 | 2019 | 2020 | 2022 |

| robotic manipulators | 5 | 2018 | 2018 | 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alginahi, Y.M.; Sabri, O.; Said, W. Reinforcement Learning for Industrial Automation: A Comprehensive Review of Adaptive Control and Decision-Making in Smart Factories. Machines 2025, 13, 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121140

Alginahi YM, Sabri O, Said W. Reinforcement Learning for Industrial Automation: A Comprehensive Review of Adaptive Control and Decision-Making in Smart Factories. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121140

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlginahi, Yasser M., Omar Sabri, and Wael Said. 2025. "Reinforcement Learning for Industrial Automation: A Comprehensive Review of Adaptive Control and Decision-Making in Smart Factories" Machines 13, no. 12: 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121140

APA StyleAlginahi, Y. M., Sabri, O., & Said, W. (2025). Reinforcement Learning for Industrial Automation: A Comprehensive Review of Adaptive Control and Decision-Making in Smart Factories. Machines, 13(12), 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121140