Combination of Finite Element Spindle Model with Drive-Based Cutting Force Estimation for Assessing Spindle Bearing Load of Machine Tools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cutting Force Estimation

1.2. Spindle Bearings

1.3. Force Influence on Spindle Bearings

2. Materials and Methods

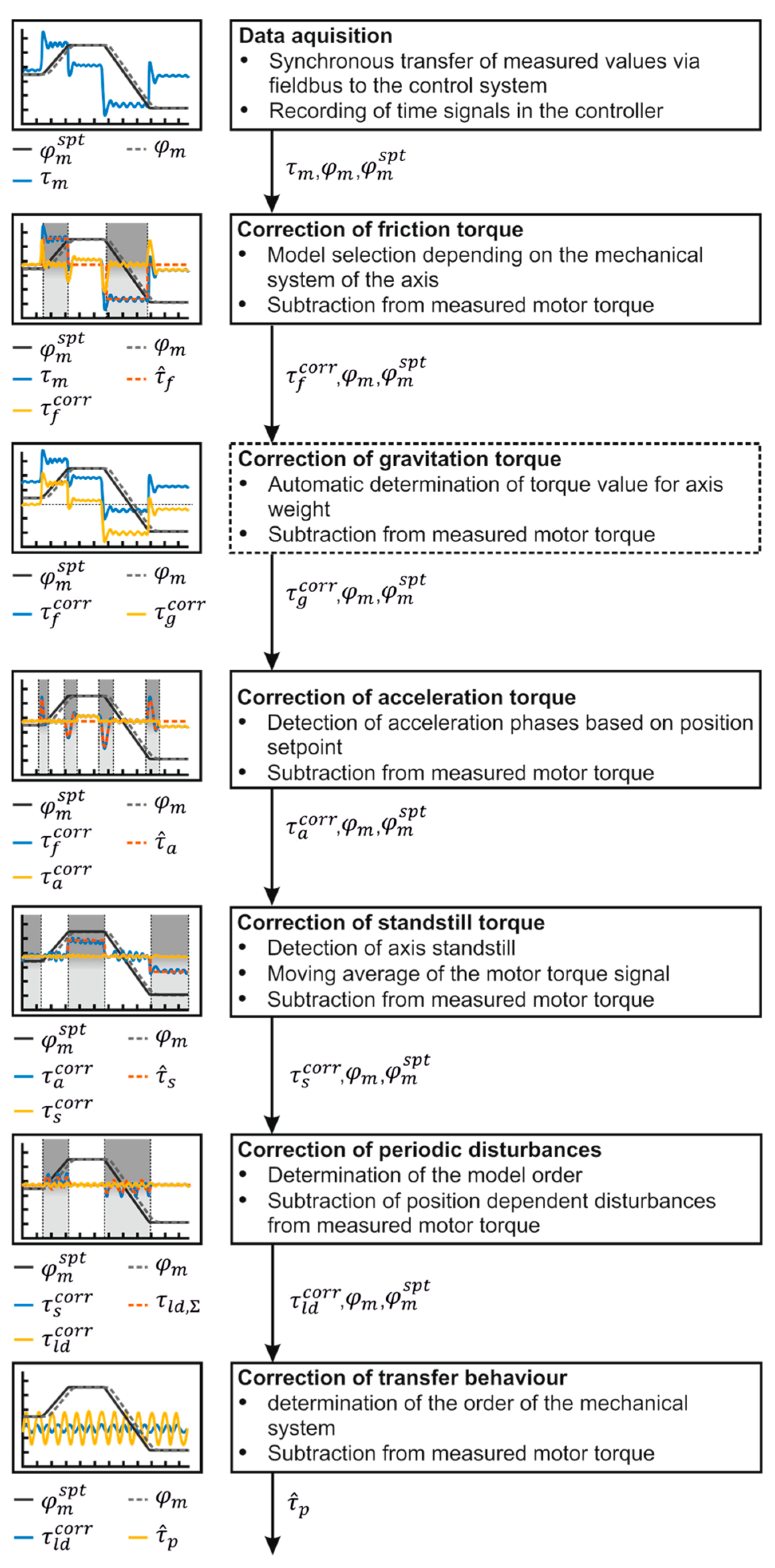

2.1. Cutting Force Estimation

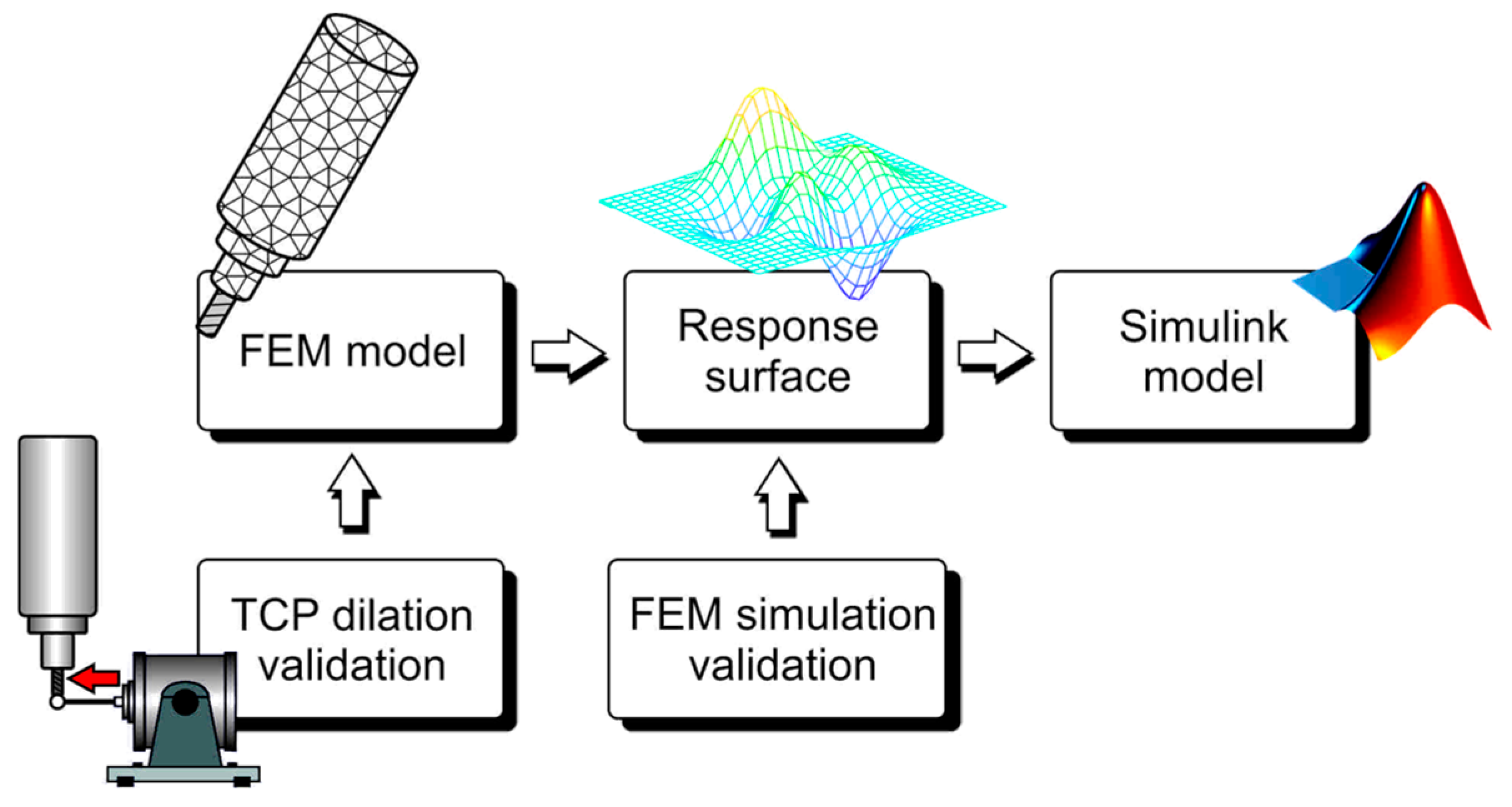

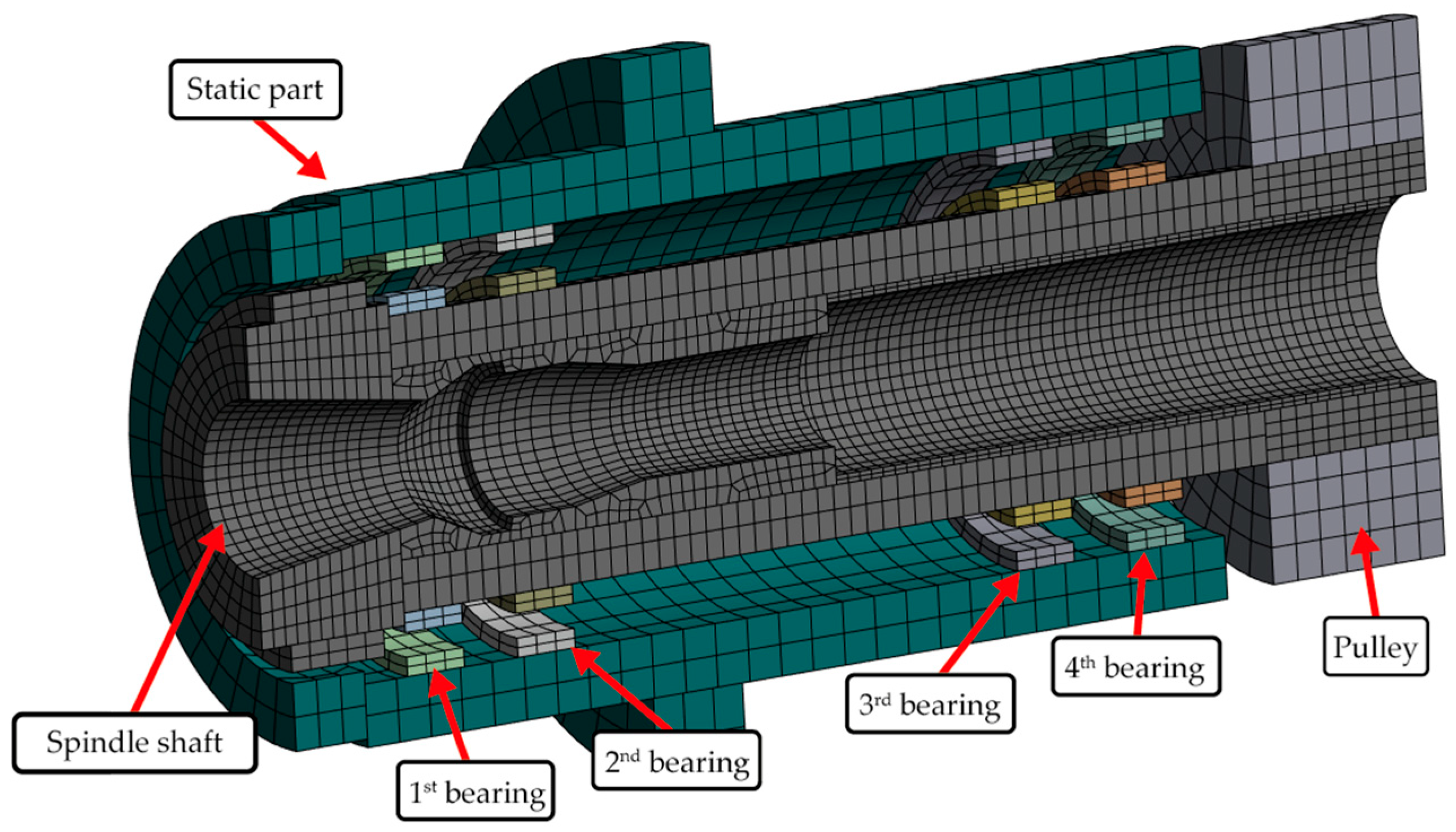

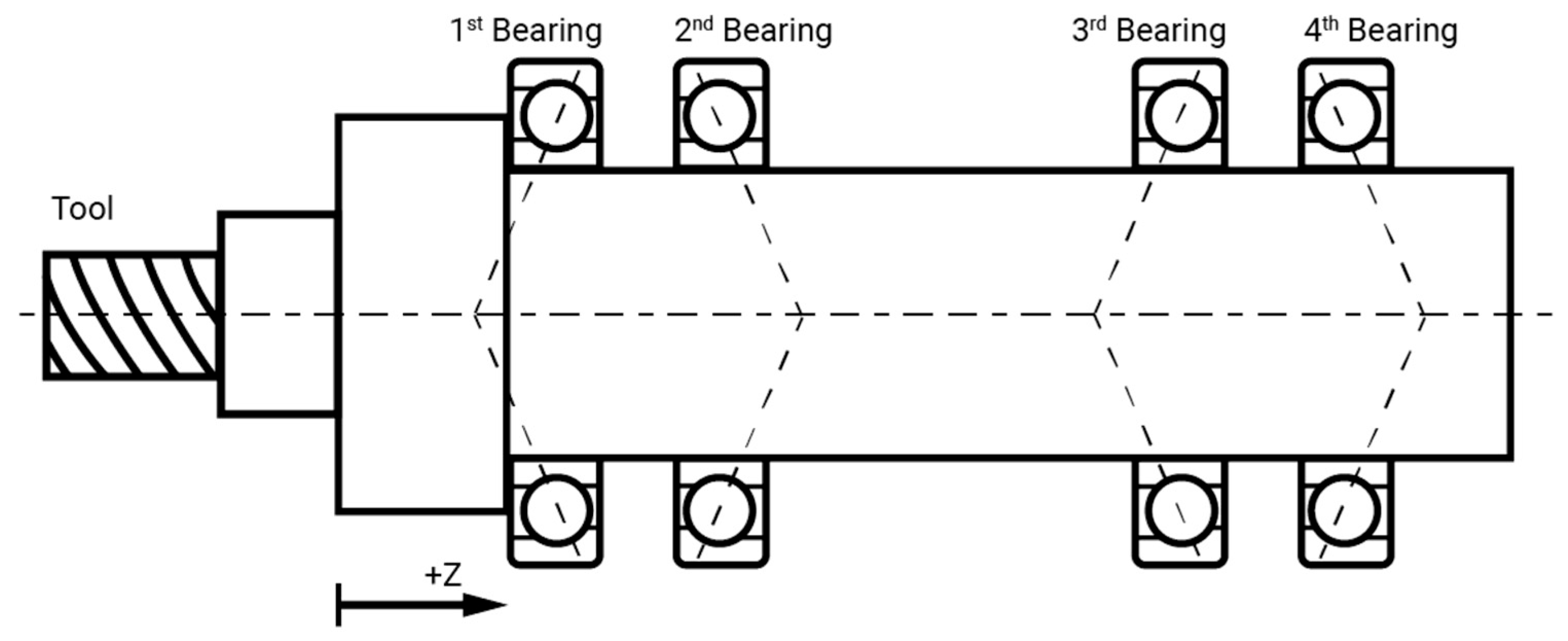

2.2. Bearing Force Estimation

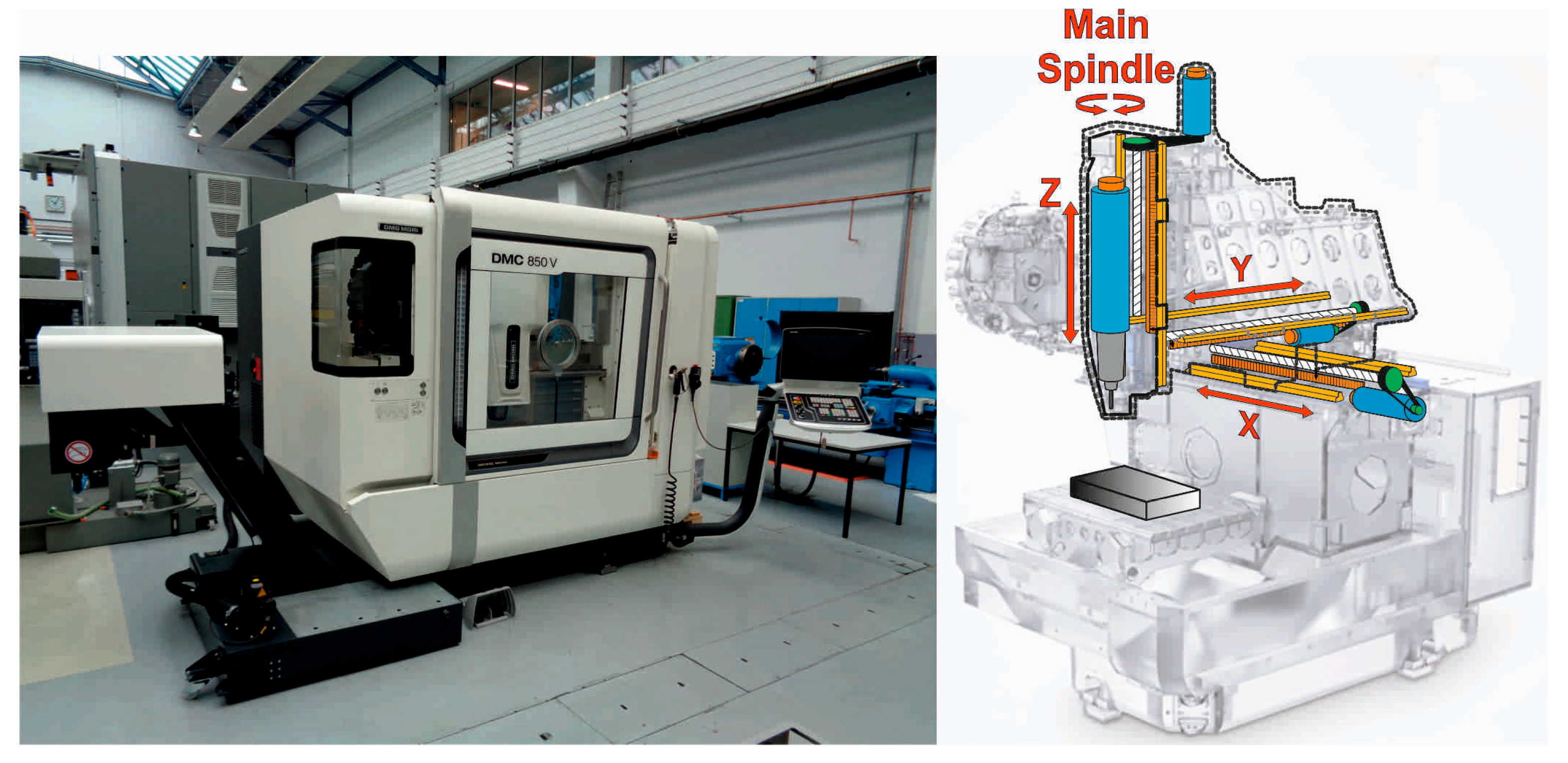

3. Experimental Setup

3.1. Cutting Force Estimation

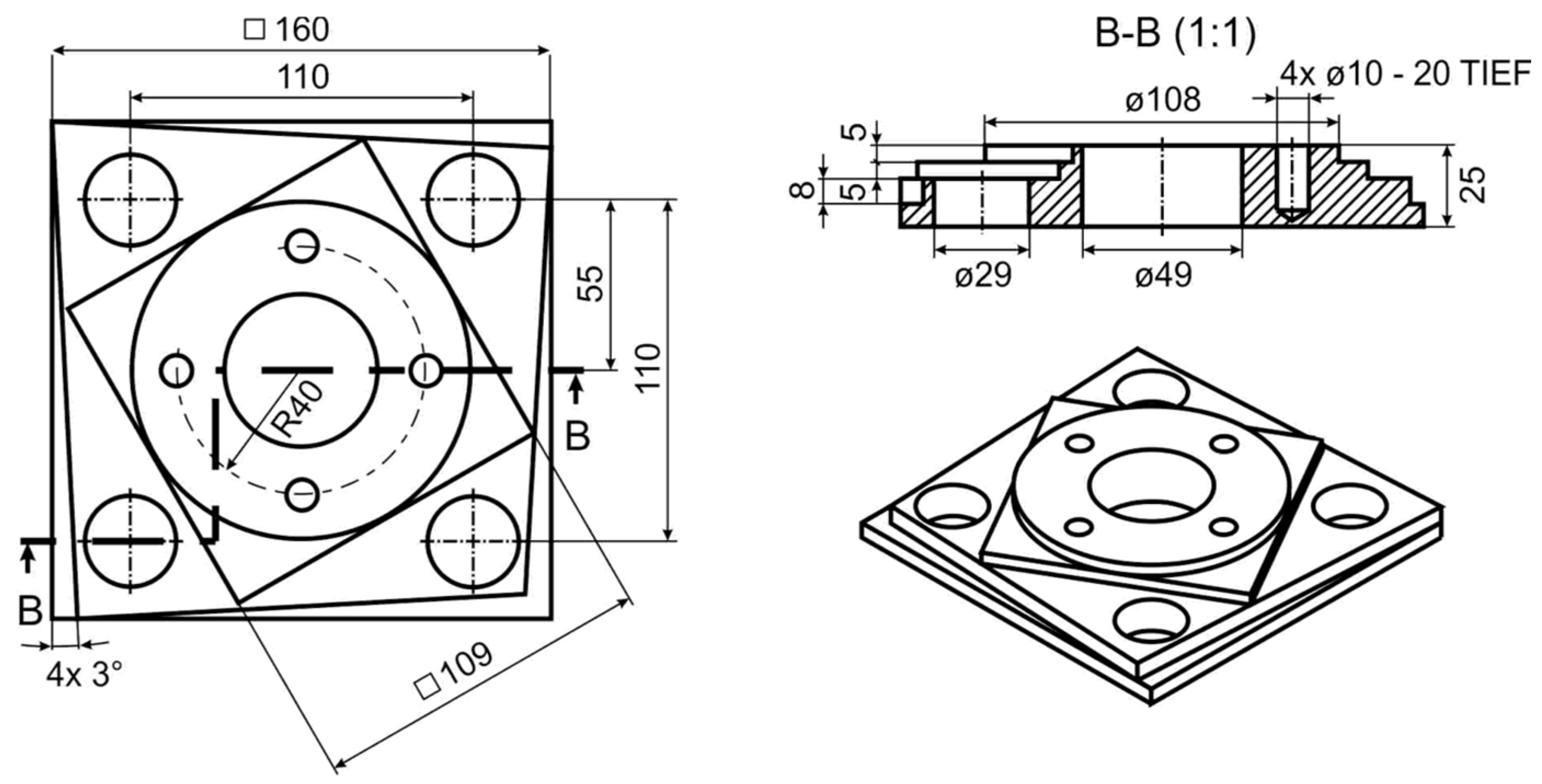

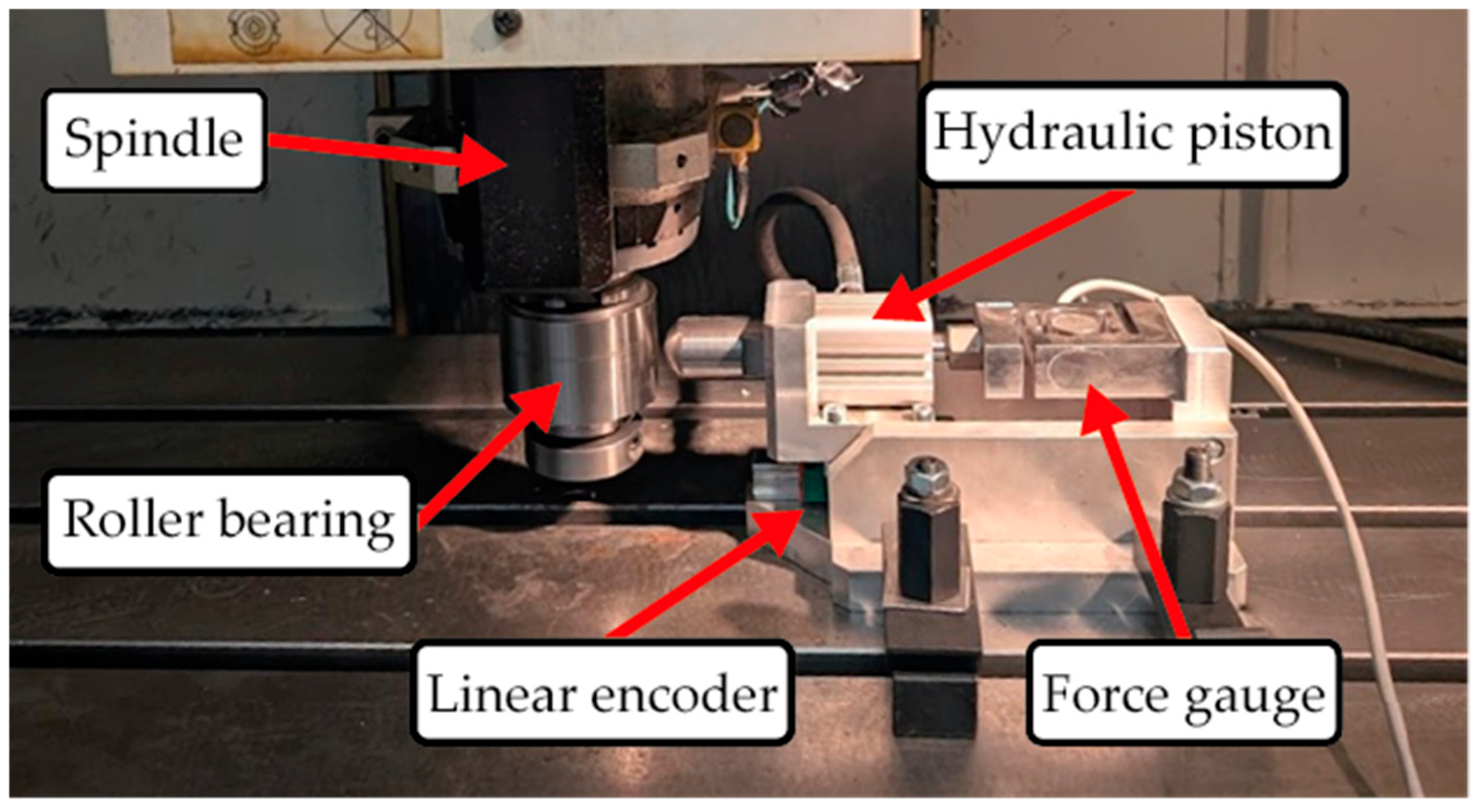

3.2. Bearing Rigidity Verification

4. Results

4.1. Cutting Force Estimation

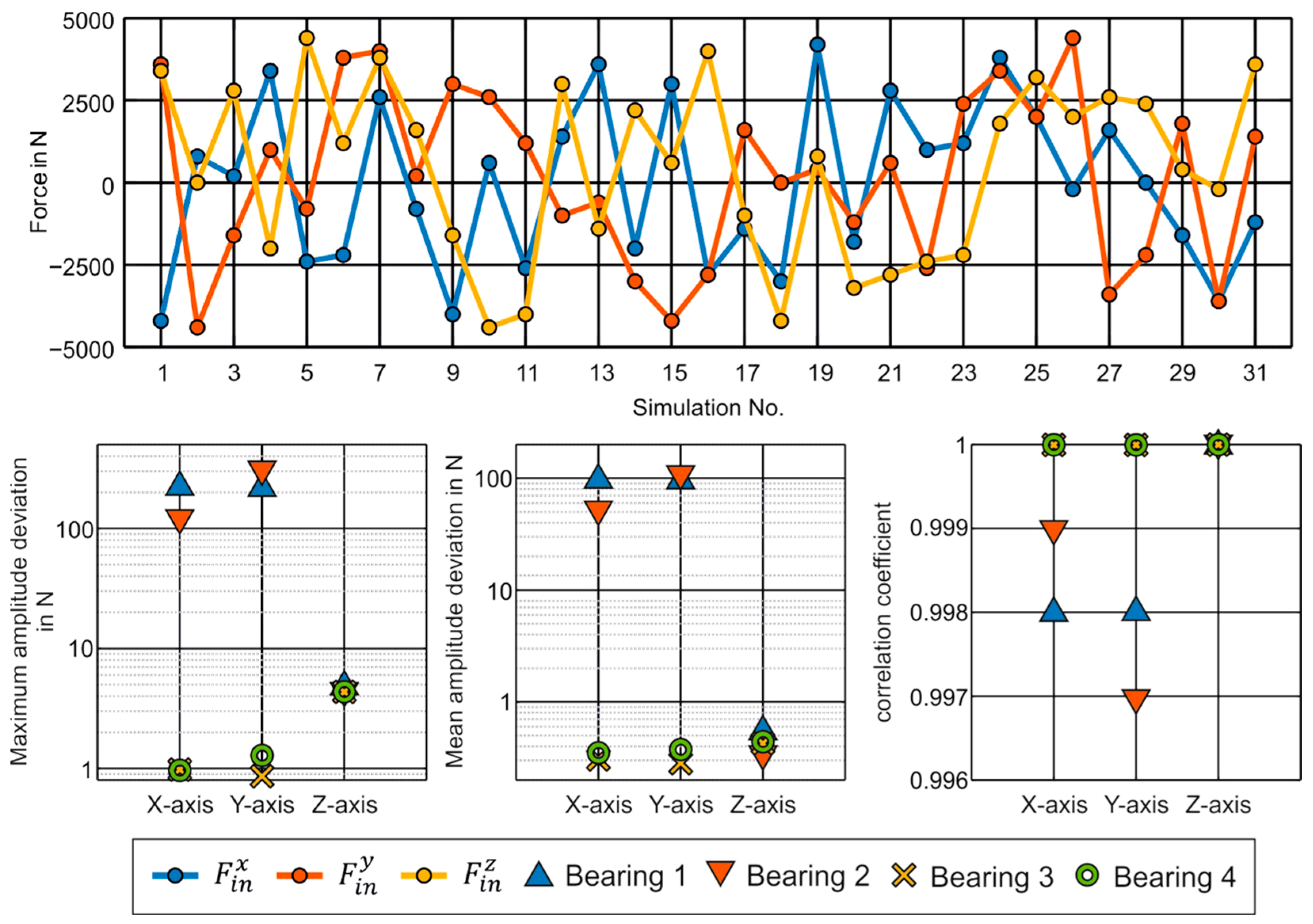

4.2. Bearing Force Estimation

4.3. Combining Cutting Estimation and Spindle Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMOP | Adaptive Metamodel of Optimal Prognosis |

| CAD | Computer Aided Design |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FMU | Functional Mockup Unit |

| MPC | Multi-Point Constraint |

| PC | Personal computer |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| TCP | Tool Center Point |

References

- Kienzle, O. Die Bestimmung von Kräften Und Leistungen an Spanenden Werkzeugen Und Werkzeugmaschinen. Z. Des. Ver. Deutscher Ingenieure 1952, 94, 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, D. Integration of Virtual and On-Line Machining Process Control and Monitoring Using CNC Drive Measurements. Doctoral Dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Kamba, A.; Takeuchi, K.; Fujita, J.; Fujimagari, Y.; Kakinuma, Y. Enhancing the Multi-Encoder-Based Cutting Force Estimation along the Stationary Axis of a Machine Tool with Multiple Inertia Dynamics. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerrer, F.; Otto, A.; Kolouch, M.; Ihlenfeldt, S. Virtual Sensor for Accuracy Monitoring in CNC Machines. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löser, M.; Otto, A.; Ihlenfeldt, S.; Radons, G. Chatter Prediction for Uncertain Parameters. Adv. Manuf. 2018, 6, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, J.; Kolouch, M.; Wittstock, V.; Putz, M. Identification of Modal Parameters of Machine Tools during Cutting by Operational Modal Analysis. Procedia CIRP 2018, 77, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamato, S.; Kakinuma, Y. Precompensation of Machine Dynamics for Cutting Force Estimation Based on Disturbance Observer. CIRP Ann. 2020, 69, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Yamato, S.; Kakinuma, Y. Mode Decoupled and Sensorless Cutting Force Monitoring Based on Multi-Encoder. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 4081–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamato, S.; Sugiyama, A.; Suzuki, N.; Irino, N.; Imabeppu, Y.; Kakinuma, Y. Enhancement of Cutting Force Observer by Identification of Position and Force-Amplitude Dependent Model Parameters. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 104, 3589–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, S.; Kadota, T.; Yamada, Y.; Nakanishi, K.; Yoshioka, H.; Suzuki, N.; Kakinuma, Y. Chatter Avoidance in Parallel Turning with Unequal Pitch Angle Using Observer-Based Cutting Force Estimation. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2018, 140, 044501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkena, B.; Bergmann, B.; Stoppel, D. Tool Deflection Compensation by Drive Signal-Based Force Reconstruction and Process Control. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamato, S.; Nakanishi, K.; Suzuki, N.; Kakinuma, Y. Development of Automatic Chatter Suppression System in Parallel Milling by Real-Time Spindle Speed Control with Observer-Based Chatter Monitoring. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2021, 22, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isshiki, K.; Sato, T.; Imabeppu, Y.; Irino, N.; Kakinuma, Y. Enhancement of Accuracy in Sensorless Cutting-Force Estimation by Mutual Compensation of Multi-Integrated Cutting-Force Observers. MIC Procedia 2021, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffler Technologies AG & Co. KG Super Precision Bearings. Available online: www.schaeffler.com/remotemedien/media/_shared_media/08_media_library/01_publications/schaeffler_2/catalogue_1/downloads_6/sp1_de_en.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Šooš, Ľ. Headstock for High Speed Machining—From Machining Analysis to Structural Design. In Machine Tools—Design, Research, Application; Šooš, Ľ., Marek, J., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020; ISBN 978-1-83962-351-6. [Google Scholar]

- AB SKF Super-Precision Bearings. 2016. Available online: https://cdn.skfmediahub.skf.com/api/public/0901d19680495562/pdf_preview_medium/0901d19680495562_pdf_preview_medium.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Bao, Z.; Liu, C.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. From Theory to Industry: A Survey of Deep Learning-Enabled Bearing Fault Diagnosis in Complex Environments. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2026, 163, 113068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 281:2007; Rolling Bearings—Dynamic Load Ratings and Rating Life. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Jacobs, W.; Brandolisio, D.; Boonen, R.; Sas, P.; Moens, D. Investigating the Effect of External Dynamic Loads on the Lifetime of Rolling Element Bearings. In Proceedings of the 9th National Congress on Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Brussels, Belgium, 9–11 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weck, M.; Hennes, N.; Krell, M. Spindle and Toolsystems with High Damping. CIRP Ann. 1999, 48, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantatalo, M.; Aidanpää, J.O.; Göransson, B.; Norman, P. Milling Machine Spindle Analysis Using FEM and Non-Contact Spindle Excitation and Response Measurement. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2007, 47, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profibus Nutzerorganisation PROFIdrive Technology and Application—System Description. Available online: https://www.profibus.de/downloads/profidrive-technology-and-application-system-description (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Schöberlein, C.; Sewohl, A.; Schlegel, H.; Dix, M. Modeling and Identification of Friction and Weight Forces on Linear Feed Axes as Part of a Disturbance Observer. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Robot. Res. 2022, 11, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöberlein, C.; Sewohl, A.; Schlegel, H.; Dix, M. Experimental Investigation and Comparison of Approaches for Correcting Acceleration Phases in Motor Torque Signal of Electromechanical Axes. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics (ICINCO 2023), Rome, Italy, 13–15 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöberlein, C.; Schleinitz, A.; Schlegel, H.; Dix, M. Identification and Correction of Periodic Fluctuations in the Motor Torque Signal of Electromechanical Axes. In Proceedings of the 5th Winter IFSA Conference on Automation, Robotics & Communications for Industry 4.0/5.0 (ARCI’ 2025), Granada, Spain, 19–21 February 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schöberlein, C.; Schlegel, H.; Dix, M. Drive-Based Identification of Transfer Function Between External Load and Motor Torque on Electromechanical Axes. In Production at the Leading Edge of Technology; WGP 2024. Lecture Notes in Production Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 71914 ACD/P4A—Schrägkugellager der Reihe “Super-Precision Bearings” SKF. Available online: https://www.skf.com/de/products/super-precision-bearings/angular-contact-ball-bearings/productid-71914%20ACD%2FP4A (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Getting Started with OptiSLang. Available online: https://ansyshelp.ansys.com/account/secured?returnurl=/Views/Secured/corp/v252/en/opti_ug/opti_ug_intro.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Darvishi, A. Translation Invariant Approach for Measuring Similarity of Signals. J. Adv. Comput. Res. 2009, 1, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- DMC V Series. Available online: https://tecnoinsrl.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/catalogo_dmc-850-v.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- ISO 10791-7:2020; Test Conditions for Machining Centres—Part 7: Accuracy of Finished Test Pieces. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Holub, M.; Vetiska, J.; Knobloch, J.; Minar, P. Analysis of Machine Tool Spindles under Load. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 821, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klic, D.; Minarcik, M.; Polzer, A.; Tuma, J.; Marek, J.; Holub, M. Digital Twin for CNC Machine Tools Design. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Conference on Mechatronics—Mechatronika (ME), Brno, Czech Republic, 4–6 December 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Tool | Cutting Depth | Feed Rate | Spindle Speed | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1  | Face milling cutter (6-edged) | 2.5 | 2600 | 974 | a: cutting depth 2.5 mm b: cutting depth 4 mm (x) and 1 mm (y) |

2  | Corner milling cutter (7-edged) | 5 | 696 | 995 | a: new cutting edges b: worn out cutting edges c: emulated tool edge breakage |

3  | Corner milling cutter (7-edged) | 5 | 696 | 995 | a: new cutting edges b: worn out cutting edges c: emulated tool edge breakage |

4  | Solid carbide milling cutter | 8 | 955 | 2387 | - |

5  | Indexable insert drill bit | - | 313 | 1646 | - |

6  | Solid carbide drill bit | - | 1190 | 5411 | - |

7  | Corner milling cutter (3-edged) | 2 | 1660 | 3247 | a: new cutting edges b: worn out cutting edges c: emulated tool edge breakage |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schöberlein, C.; Klíč, D.; Holub, M.; Schlegel, H.; Dix, M. Combination of Finite Element Spindle Model with Drive-Based Cutting Force Estimation for Assessing Spindle Bearing Load of Machine Tools. Machines 2025, 13, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121138

Schöberlein C, Klíč D, Holub M, Schlegel H, Dix M. Combination of Finite Element Spindle Model with Drive-Based Cutting Force Estimation for Assessing Spindle Bearing Load of Machine Tools. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121138

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchöberlein, Chris, Daniel Klíč, Michal Holub, Holger Schlegel, and Martin Dix. 2025. "Combination of Finite Element Spindle Model with Drive-Based Cutting Force Estimation for Assessing Spindle Bearing Load of Machine Tools" Machines 13, no. 12: 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121138

APA StyleSchöberlein, C., Klíč, D., Holub, M., Schlegel, H., & Dix, M. (2025). Combination of Finite Element Spindle Model with Drive-Based Cutting Force Estimation for Assessing Spindle Bearing Load of Machine Tools. Machines, 13(12), 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121138