1. Introduction

In the field of medicine, surgery is one of the most essential treatments that provides diagnosis and cure for various injuries, traumas, and pathological issues through operative procedures [

1]. The emergence of robotic technology in the surgical fields has revolutionized the way challenging procedures are carried out, enhancing precision, lowering operating risks, and shortening recovery periods. Since their development in the late 20th century, surgical robots have undergone tremendous evolution, providing improved capabilities that exceed the constraints of human dexterity, precision, and consistency [

2]. Recent developments, including the integration of artificial intelligence, have further enhanced these technologies to include real-time data analysis and semi-autonomous surgical functions. These robots are designed in order to help surgeons perform minimally invasive surgeries (MISs), which save patients from discomfort, reduce incision sizes, and speed up their recuperation periods [

3].

The design or architecture of surgical robots plays a crucial role in their performance, which has been divided into three categories, i.e., serial robots, parallel robots, and hybrid robots [

4,

5]. Among these three, serial robots are utilized frequently. They are made up of a chain-like structure consisting of multiple connected segments, which enables a broad range of motion and precise placement of tools and end effectors. One of the most readily available serial robots is the da Vinci Surgical System, which was first introduced in the early 2000s [

6]. Some other serial surgical robots presented in the literature include Neuroarm [

7], the Sehance Surgical System [

8], Mirosurge [

9], Raven [

10], and Versius [

11], which have proved their potential in MISs but have drawbacks including reduced stiffness and high inertia [

12].

Parallel manipulators, on the other hand, offer high precision and stiffness as well as compactness, positional accuracy, rigidity, and high payload to weight ratio. Due to these benefits, they are employed in various medical applications like guiding spinal pedicle screws placement, drill guiding for distal locking screws in intramedullary nailing, endoscopic ventriculostomy, hip arthroplasty, etc. [

13]. A parallel manipulator designed for orthopedic surgeries includes a six degrees of freedom (DOF) fixator [

14] and MBARS [

15]. Similarly, a parallel robot was proposed by [

16] facilitating skull surgeries, a micro-robot for ophthalmic surgeries was designed by [

17], and the parallel robot named MARS was described in [

18] for spinal cord procedures. Despite all the benefits, the use of parallel manipulators is limited due to their constrained workspace, but newer models and designs are still being proposed for expanding the span of their applications in surgical fields [

19].

Hybrid surgical robots (HSRs) seek to address these shortcomings by combining both parallel and serial architectures, providing a well-balanced solution that refines both operating scope and precision [

20]. They are made to carry out a variety of surgical procedures with exceptional precision and dependability, ensuring motion in multiple dimensions [

21]. Moreover, these are suitable for a variety of surgical operations, especially those that call for minimal invasiveness and great precision [

18]. Given these merits, a hybrid robot named PARASURG 5M was proposed, with its detailed kinematic and dynamic modeling, as a viable solution for MIS by [

22]. Another robot was designed, consisting of two modules: the PARAMIS robot and the serial position module. It provided the required motion control and in-depth workspace analysis for different surgical limitations and applications [

23]. A 3-DOF parallel manipulator combined with a single-DOF prismatic joint was described in [

24]. A 5-DOF hybrid manipulator was designed and optimized on the basis of global performance index (GPI) using a pattern search method targeting spinal cord MIS [

25]. A study reported a multi-DOF HSR using two bendable serial segments consisting of parallel universal joint-based bending linkages, which aimed for the manipulation of soft tissues with a positional accuracy error of below 1.2 mm [

26]. For the treatment of spinal and orthopedic conditions, an 8-DOF HSR was configured using linear actuation and PID control [

27]. For changing the position and orientation of the tools, a 7-DOF hybrid mechanism was introduced. It was a combination of a 4-DOF SCARA and a 3-DOF (2R1T) parallel wrist [

28]. Another study presented by [

29] put forward a concept of a 4-DOF HSR based on haptic response for laparoscopic surgeries. For dental implants, a parallel platform-based 5-DOF hybrid robot was designed and optimized based on neural networks. The optimization algorithm targeted the limited workspace of the parallel platform by minimizing its joint displacements [

30]. A miniature palm-sized HSR has been introduced recently for ophthalmic surgeries based on a double five-bar mechanism, a decoupled ball joint, and a tool cartridge mechanism [

30]. Both HSRs and parallel surgical manipulators have experienced major improvements in recent years. For example, the authors in [

31] have performed a kinematic study of multiple redundant parallel mechanisms in orthopedic fracture reduction surgery, finding a design with significantly better tilting. On the same note, ref. [

32] not only optimized a 3-DOF parallel robot platform to perform laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas but also employed sophisticated genetic algorithms to ensure that the resulting system was highly precise and had a big workspace, which was conducive to complex anatomy. Detailed reviews regarding hybrid parallel–serial manipulator systems also emphasize the revived enthusiasm to combine the benefits of serial and parallel mechanisms (high stiffness, accuracy, and big workspace) in modern designs [

4]. The researchers in [

33] have demonstrated a new 3PUS-PRU parallel mechanism module attached to a 6-DOF hybrid machine, which indicates that parallel mechanisms are innovative and can be used in contemporary hybrid robots. Mentioning such current studies on parallel and hybrid machines will be more helpful to set the context and the originality of the proposed research, as suggested by the reviewer. Motivated by the effectiveness of the HSRs for several surgical procedures, an 8-DOF miniaturized HSR has been proposed in this paper.

The proposed HSR consisting of a 6-DOF parallel platform and a 2-DOF serial manipulator leverages the potentials of both mechanisms, but its weakness lies in the confined range of motion of the parallel platform, which has a closed-loop architecture. This drawback limits the dexterity of the HSR, reduces its precision, and risks the mobility of the robot by limiting its reach to deep or complicated anatomical surgical sites. Consequently, surgeons are compelled to reorient the robot extensively at the expense of the HSR’s performance, resulting in longer surgery duration, enhanced procedure complexity, and possible decreases in surgical precision. To overcome this drawback, this research aims to analyze the design of the HSR’s parallel platform through multi-stage analysis and optimization of the parallel platform’s design based on three crucial performance parameters.

The multi-stage analysis focuses on three different analyses, including kinematic analysis, geometrical analysis, and singularity analysis. These analyses highlight the limitations of the HSR’s parallel platform and form the basis for its design optimization. After the platform’s optimization, evaluation of its workspace was carried out. Finally, the optimized model of the HSR’s parallel platform is tested for its motion-planning abilities for a predefined 3D trajectory. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first in the field of HSRs that provides a detailed multi-stage analysis of the HSR’s parallel platform followed by its design optimization through two different optimization approaches. The article is structured in the following manner. The detailed description of the HSR’s design is provided in

Section 2. The following

Section 3 discusses the multi-stage analysis of the HSR’s parallel platform. The design of the platform has been optimized in

Section 4. Motion planning of the optimized platform has been analyzed in

Section 5. The results of this study have been thoroughly discussed in

Section 5 followed by the conclusion in

Section 6.

2. The HSR’s Architecture

This section gives the virtual representation of the HSR, explaining how its components are attached. The design of the HSR mainly consists of two distinct parts: a 6-DOF parallel manipulator and a 2-DOF serial manipulator. The purpose of the parallel platform is to approach and aim for the position of interest in the human body, whereas the serial manipulator handles and adjusts the position and orientation of the surgical tool. In this way, both components of the HSR help the surgeon in performing the surgical procedure swiftly and efficiently.

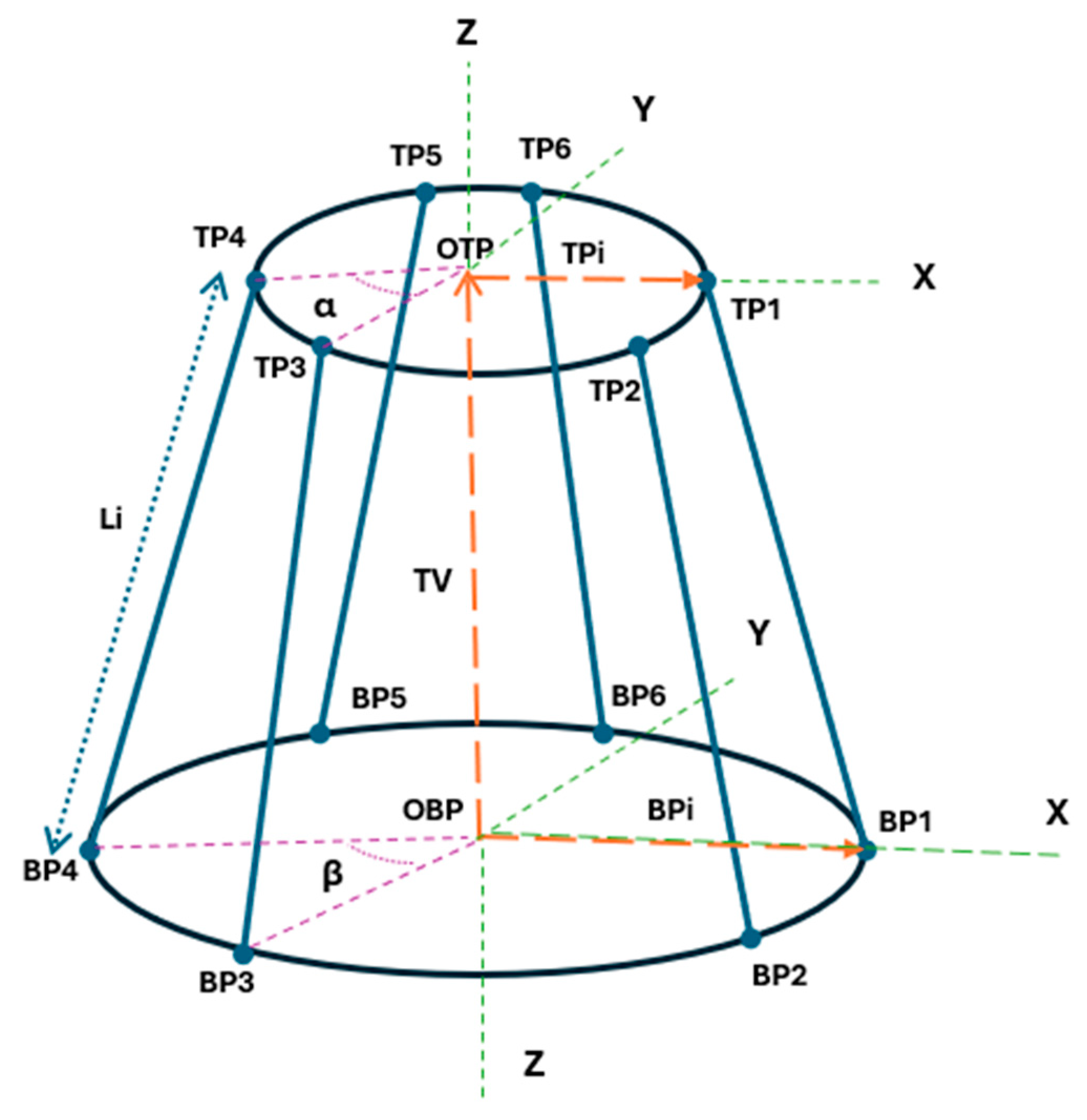

Figure 1 illustrates the design of the HSR with its labeled components. All the dimensions of the HSR, including the lengths of the links, angle between joints, radii of top and bottom plates, etc., are listed in

Table 1. These parameters play a crucial role in designing the HSR and have a huge impact on its performance.

Table 1.

Dimensions of the HSR.

Table 1.

Dimensions of the HSR.

| Part Name | Dimension |

|---|

| Base Radius of Serial Manipulator (c) | 7 mm |

| Serial Manipulator Link 1 (l1) | 20 mm |

| Serial Manipulator Link 2 (l2) | 20 mm |

| Lower Plate Radius (R) | 30 mm |

| Upper Plate Radius (r) | 20 mm |

| Upper/Lower Plate Thickness (w) | 15 mm |

| Actuated Leg Length (L1) | 45 mm |

| Upper Plate Joint Angles (α) | 30° |

| Lower Plate Joint Angles (β) | 60° |

Figure 1.

Design of the HSR with a description of all components. LP: Lower platform; UJ: universal joints; AL: actuated leg; SJ: spherical joint; UP: upper platform; SM: serial manipulator; RJ: revolute joint; LK: link.

Figure 1.

Design of the HSR with a description of all components. LP: Lower platform; UJ: universal joints; AL: actuated leg; SJ: spherical joint; UP: upper platform; SM: serial manipulator; RJ: revolute joint; LK: link.

Figure 2.

Vector diagram of the HSR’s parallel platform depicting position vectors, frame of reference, and distribution of joints on top and bottom plates.

Figure 2.

Vector diagram of the HSR’s parallel platform depicting position vectors, frame of reference, and distribution of joints on top and bottom plates.

2.1. Two-Link Serial Manipulator

The 2-link serial manipulator of the HSR, also known as a robotic arm, is designed to facilitate two independent DOFs for enabling precise motion of the manipulator. The serial linkage is formed by the combination of two rigid links, which are interconnected in a series formation directly connected to the top plate of the parallel platform, designed to aim for the target position and configuration. Due to its connection with the top plate of the parallel platform, its motion is strictly coupled with this movable platform. The motion in the parallel platform also results in the motion of the serial manipulator while reorienting its frame of reference. The serial manipulator will now perform the task in the redefined frame of reference and work volume while maintaining synchronization with the parallel platform. It is the part of the surgical robot that also contains a tool post or tool guide for the attachment of the surgical tool. This serial manipulator is designed to be lightweight but structurally rigid and stable with minimal inertia and adequate mechanical strength.

The main components include two rigid links, revolute joints, linear actuators, a fixed base, and an end effector interface. The connection between the HSR’s parallel platform and the base of the serial manipulator is supported by a base revolute joint, which is the first actuated joint of the serial linkage. This base joint enables the first DOF of rotational motion by joining the first rigid link to the base. This first link acts as the fundamental component in the motion of the serial manipulator, as it transmits motion to the second rigid link of the manipulator. At the intersection of both rigid links, there is an elbow revolute joint, which is responsible for the second DOF. The second link is further extended to the end effector interface, which is the point of tool attachment. When the top plate of the parallel platform moves, the actuated joint between the plate and the first link also initiates the motion of the serial manipulator. This motion is then transferred to the second rigid link, which finally moves the tool in the desired direction to perform the desired task by the surgeon. In this way, the flexible yet robust structure of the serial manipulator executes the minimally invasive surgical tasks precisely and smoothly.

Figure 1 shows the assembly of the components of the 2-link serial manipulator of the HSR.

2.2. Parallel Platform

This parallel platform is similar to a hexapod in design since it contains six actuated links/legs and is well known for its high stiffness and stability [

34]. Moreover, the design consists of two upper and lower plates, universal joints, ball and socket joints, and linear actuation. The legs are attached between these plates at a certain angle using both kinds of joints. This particular design of parallel platform facilitates a total of six DOFs, i.e., three rotational motions and three translational motions.

The compact structure of the parallel platform is designed so that the bottom plate serves as the fixed foundation of the entire structure, and the legs are attached to it through universal joints at a specific angle. Essentially, these universal joints are attached to the base plates at specific angles relative to each other, determining the position of the links/legs on the plate, as depicted in

Figure 1. These joints facilitate the smooth and jerk-free tilt of the actuated legs and also ensure safety from undesired torsional stress. The top plate is the movable platform, which is directly in contact with the serial manipulator. It is supported by the six actuated legs attached to it using ball and socket joints or spherical joints. These spherical joints enable an unhindered multi-dimensional tilting and rotation of the top movable plate. The motion is primarily driven by six linear actuators attached to each leg, which produce an independent motion for each leg. The closed-loop control of the system ensures the synchronization of the motion of each actuator. Linear actuation is preferred in the case of the HSR due to its benefits like high precision, high torque, and smooth control [

35]. In this way, the compact and robust structure of the parallel platform provides support and stability for the serial manipulator as well as the whole HSR, helping the surgeons perform their intended surgical procedures with precision.

4. Design Optimization

One of the major objectives of this study is to achieve a well-conditioned and precise hybrid surgical robot through design optimization of its parallel platform. But accomplishing this goal is difficult with higher values of GCN. Adjustments of geometrical, kinematic, and performance parameters are required in order to refine the workspace of the platform by reducing the singular configurations [

46,

47]. So far, we have assessed the performance of the platform on the basis of its condition number, but for performing the surgical tasks precisely, some other parameters also play a crucial role, which require analysis as well. Keeping this in mind, the design of the HSR’s parallel platform has been optimized by considering three core parameters, i.e., GCN, actuator forces, and stiffness. The target is to achieve a trade-off between these three parameters by changing the geometric properties of the platform during the optimization process. An overview of these performance indices has been provided. Moreover, this section presents a single-objective optimization of the platform targeting reduction of its GCN mainly. In the next phase, multi-objective optimization is proposed and explained for obtaining a more efficient and versatile design of the HSR’s platform. Finally, a workspace evaluation of the optimized design of the HSR’s platform has been provided, which helps in understanding the improved performance of the platform as well as its enhanced range of motion.

4.1. Performance Indices

The parallel platform’s design optimization targets three performance indices: GCN, actuator force, and stiffness, because together they represent the information about the system’s kinematic dexterity, mechanical effort, and load-bearing capacity that are essential for safe and accurate surgical procedures. GCN is a measure of Jacobian conditioning that determines to what extent the actuator motions are optimally mapped into end effector motions and will therefore be a measure of the risk of singularities and susceptibility to input errors. Actuator forces obtained from the inverse of the Jacobian are the actual forces needed by the actuators to follow the trajectory or reject external wrenches. Stiffness, which is defined by the actuator stiffness matrix and Jacobian, controls the deviation of the platform under load and the resulting posture error.

These three metrics are tightly coupled as a high GCN indicates bad conditioning, and it will amplify errors, which in return usually require more force from the actuator to perform the same task, while a lack of stiffness allows these amplified forces to cause large deflections that will lead to the loss of even more accuracy and possibly change the effective Jacobian. Hence, neglecting any one of these indices during design therefore produces certain types of failure, such as ignoring GCN risking singularities and uncontrollable sensitivity; ignoring high actuator force use resulting in excessive use of energy, as well as wear and thermal or vibrational problems; and stiffness issues in the actuator system potentially causing unacceptable deflections and loss of positional accuracy, as well as unsafe interaction with tissue. Accordingly, the simultaneous optimization of all three indices must be realized in order to design a surgically robust and efficient parallel platform. A detailed description of the condition number and GCN have already been provided previously, so this section will cover the other two performance indices, i.e., actuator force and stiffness.

4.1.1. Actuator Force

Actuators in parallel platforms generate forces that are required to execute the desired task. These forces bring about motion by effectively distributing the applied external wrench (forces and torques) across the whole platform’s structure [

48,

49]. There exists a relation between these forces and an applied external wrench that is defined in terms of the Jacobian matrix. This relation is given in Equations (24) and (25).

where

is the platform’s actuator force,

is inverse of the Jacobian matrix, and

is the applied external wrench. Equation (25) gives the norm of actuator forces

, which is intended to be minimized.

As mentioned earlier, the external wrench is distributed equally among the six links of the platform; it is safe to assume that the platform is a rigid body, and it does not face any kind of deformation. Moreover, all the link forces associated with the platform must be linearly independent from each other, otherwise they will have an impact on the Jacobian matrix. The Jacobian matrix may become singular, and the HSR’s platform may experience loss of degrees of freedom.

4.1.2. Stiffness

The stiffness of the HSR plays a crucial role in its motion and precision as it resists the external disturbances, refraining the system from undesired deflection and permanent damage. The overall stiffness of the HSR is highly dependent on the stiffness values of both of its components, mainly the parallel platform. In the parallel robotic platform, the stiffness value is dictated by three main factors, i.e., actuator configuration, distribution of forces throughout the platform’s links, and the structural design of the platform. The relation between all these factors and the platform’s stiffness is described by implementing linear small displacement assumptions that state that the parallel platform’s displacements and rotations

about a pose are so small that a first-order linear relation exists between them. The Jacobian matrix derived in the previous section helps to map a relation between the displacements and rotations of the platform

and change in actuator lengths

by Equation (26). The sign

denotes small changes in displacements, rotations, and actuator lengths.

According to actuator force-displacement law:

where

is the stiffness matrix of all six platform’s actuators [

50]. For determining Cartesian stiffness, the wrench

) equilibrium must exist in the system which is defined as:

Substituting Equations (27) and (28) in Equation (29) results in Cartesian stiffness

The platform’s stiffness matrix is a symmetrical matrix containing singular values , which indicate stiffness in the corresponding principal axes. These singular values can be obtained by implementing the concept of singular value decomposition (SVD). The least singular value is the weakest stiffness of the platform. In order to enhance the precision and performance of the platform as well as the HSR, the diagonal of the minimum of these least singular values will be maximized in this optimization problem.

4.2. Single-Objective Optimization

The increase in efficiency of the 6-DOF parallel platform is directly proportional to minimizing the GCN values of its Jacobian matrix. This is accomplished by optimizing the design of the platform by changing its geometrical parameters. In this case, the design variables are the angles between the joints of both upper and lower plates (

) and the radii of both plates (

), as described by variable

in Equation (31). Throughout the optimization process, these parameters were changed to observe their effect on the values of the GCN.

The design constraints for this optimization technique have been presented in Equations (32) and (33). Referring to

Figure 2, the joint angles of both plates should be:

The radius of lower and upper plate should be:

The aim of this optimization problem is to obtain a design for the HSR’s parallel platform with the lowest value of GCN; this goal is defined by employing a single-objective function

. This objective function is the GCN computed over a set of discrete poses for all the designs of the parallel platform obtained by varying design variables described in Equation (31). The Jacobian matrix

and condition number

at each pose are determined. The values of condition number

govern the objective function

, and minimizing

reduces the kinematic conditioning of the parallel platform. The calculation of single-objective function

is explained by the following equations.

For each pose

,

defines the position and orientation of the upper moving platform.

where x is the parallel platform’s candidate design,

n is the number of discrete poses, and

is the condition numbers of the platform computed for x design at a certain pose

. The technique employed for single-objective optimization is an evolutionary algorithm known as genetic algorithm (GA). The process began by initializing the optimization process by deciding the performance parameters for GA, provided in

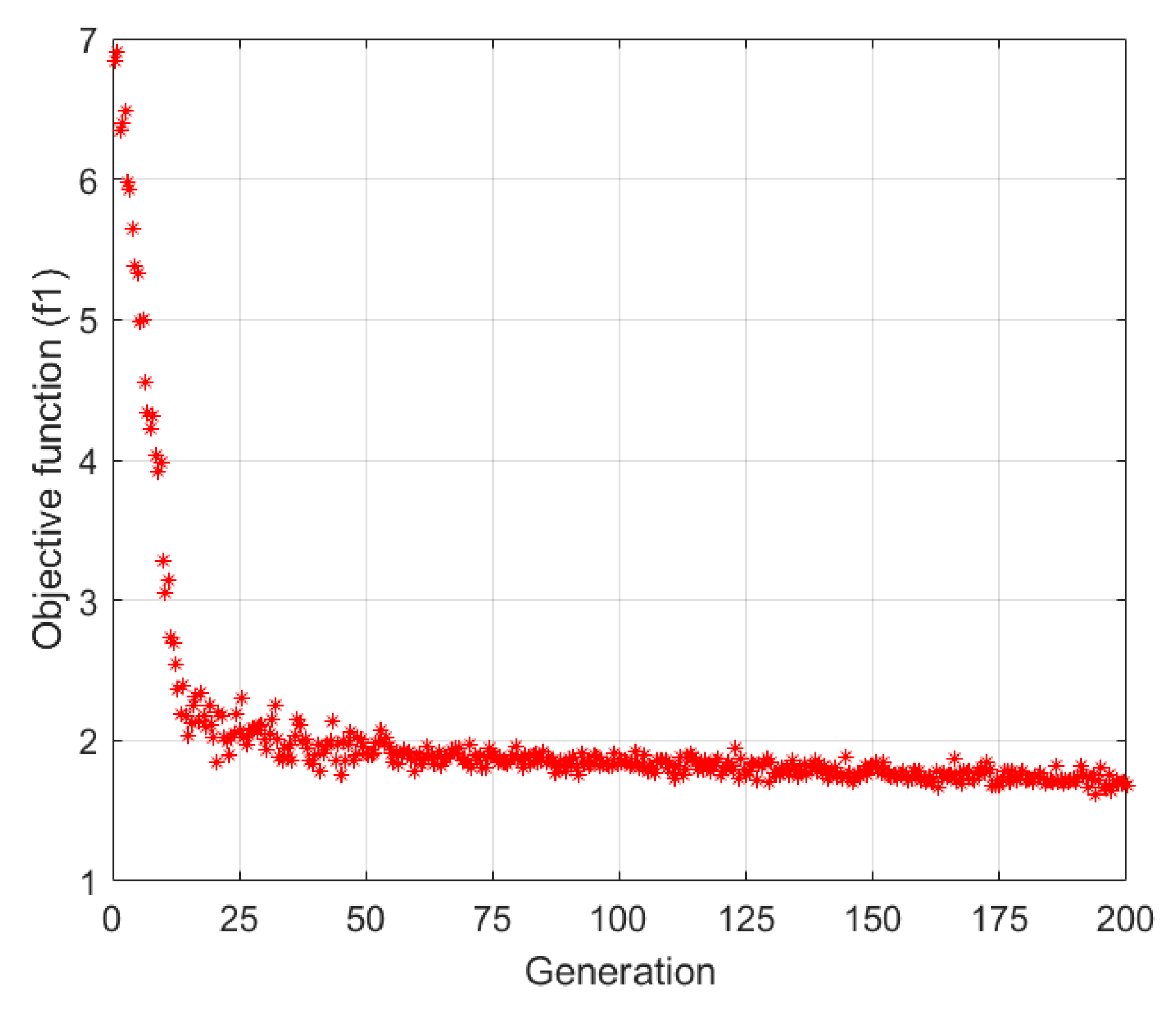

Table 3a. The next step was the calculation of the fitness function values followed by the selection of operator, crossover, and mutation among the populations and, finally, evaluation of the results. The operator selected in this case was rank-based selection, which helped in determining the best solution among the evolving generations of parents and offsprings. The optimization process was run for 200 iterations in order to have a good convergence of Pareto optimal solutions. The results of single-objective optimization are illustrated by

Figure 5. The results depict a monotonic improvement in the objective function

, which began around the 55th generation and continued till the 200th generation, where the optimization process terminated upon meeting the convergence criteria. From the trend of the curve, it is evident that the GCN has been effectively reduced by improving the platform’s design through optimization. An optimal value of 1.78 has been obtained. No doubt the GA demonstrated satisfactory results in terms of GCN evaluation, but the issues related to stiffness and actuator forces still persisted. The optimization results of this technique are summarized in

Table 3b,c.

The values of stiffness and norm of actuator force in this case are 542 N/m and 105 N. This occurred due to the fact that single-objective optimization focuses on refining the value of one objective at a time and may find it difficult to tackle multiple performance parameters at the same time. The requirement of design optimization is to attain a trade-off among all three parameters without compromising any of them. Hence, these simulations proved that it cannot be achieved through single-objective optimization, so the next goal is to simultaneously optimize all three parameters through multi-objective optimization.

4.3. Multi-Objective Optimization

Multi-objective optimization deals with the simultaneous optimization of two or more objectives without prioritizing any single one. In comparison with single-objective optimization, this technique generates a set of optimal solutions with no particular solution that is strictly better than the other one. Over the years, researchers have employed different multi-objective optimization techniques based on weighted sum methods and evolutionary algorithms. Among these, the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II) has been used widely due to its benefits like quick non-dominating sorting, a crowding distance approach, and the concept of elitism [

51]. This rapid non-dominating sorting assigns Pareto fronts to the solutions based on dominance criteria, and crowding distance is used to make these solutions diverse and unique from the previous ones. The concept of elitism enhances the convergence of optimal pareto fronts by preserving the best solutions among parents and offsprings.

Figure 6 provides a detailed flowchart of how NSGA-II performs multi-objective optimization. Initially the generation counter (i) begins with a zero value and stops upon fulfilling the conditions of the dual termination criterion. The optimization algorithm terminates either when the solution converges and no considerable changes or improvements are observed over several generations or when the maximum number of generations is attained.

As the name suggests, evolutionary algorithms including NSGA-II mimic the phenomenon of natural selection. The initial set of solutions that evolves over the course of optimization process is known as population, whereas new solutions that are being generated from this population are termed as offsprings. The generation of both population and offsprings is dependent on key parameters known as crossover, selection, mutation, and crowding distance. The crossover is responsible for generating offspring from the initial population, selection criteria help in discarding incompetent solutions, mutation aids in evaluating optimal solutions, and crowding distance maintains diversity among generations while solving the optimization problem. Any optimization problem is defined by an objective function, which in the case of the HSR’s platform is described by the following Equation (36).

In the above equation, x is the candidate design of the parallel platform,

is the first objective function,

is the second objective function,

is the norm of actuator forces for x design which is to be minimized,

denote wrench values for the platform’s x design,

is the third objective function,

is the stiffness matrix of x design, and

are singular values for each actuated leg of the x design. The design variables and constraints for the NSGA-II optimization are the same as they were defined for the single-objective optimization presented by the set of Equations (32)–(35). The key parameters necessary to decide the course of the platform’s optimization are listed in

Table 4a.

The results began to converge around 160 iterations, and at this stage it was determined that optimal solutions for the HSR’s platform had been achieved. It should be kept in mind that NSGA-II-based multi-objective optimization algorithm yields a set of Pareto-optimal solutions instead of a single optimum solution, as presented in

Figure 7. The goal of this approach is to find a representative set of the best trade-off solution, often termed as Pareto fronts, from which the user can choose the most suitable design based on their requirements. Referring to the Pareto fronts depicted in

Figure 6, the final design model for the HSR’s parallel platform was selected based on thorough observations and intuitions, ensuring a reasonable balance between all three objective function values. Minimizing the GCN along with other parameters was a major concern because it directly impacts the performance of those parameters as well as the dexterity of the whole system. Maximum values of GCN were recorded between 1 and 7, and the norm of actuator forces varied between 5 N and 25 N. The best trade-off observed between these two parameters was 2.36 and 7.55 N. In the graph depicting the optimal values of GCN plotted against the stiffness of the platform, the achievable value for GCN is around 2.12, and for stiffness, it is 1356 N/m. The trade-off values for the norm of actuator forces and stiffness were determined to be 8.28 N and 1274 N/m. Based on the observations and results of multi-objective optimization, the design variables and objective function values of the optimized model of the HSR’s parallel platform are in

Table 4b,c.

4.4. Workspace Evaluation

Once the platform is optimized, the next step is its workspace analysis. Workspace analysis determines the feasible range of motion where the platform can perform the desired tasks with stability and precision without reaching singular configurations. Moreover, surgical operations and procedures demand a highly reliable robot that can place the tool and perform the required task precisely. The manipulator’s workspace determines the range of positions that can be achieved by the mechanism considering its geometric and structural constraints. In other words, the workspace also defines the space in which the inverse kinematics solutions of the manipulator exist without any singularity. Several approaches can be used for the evaluation of the manipulator’s workspace, including analytical, numerical, and experimental methods [

52]. Of these, numerical methods are commonly used since they can easily deal with complex geometries and constraints.

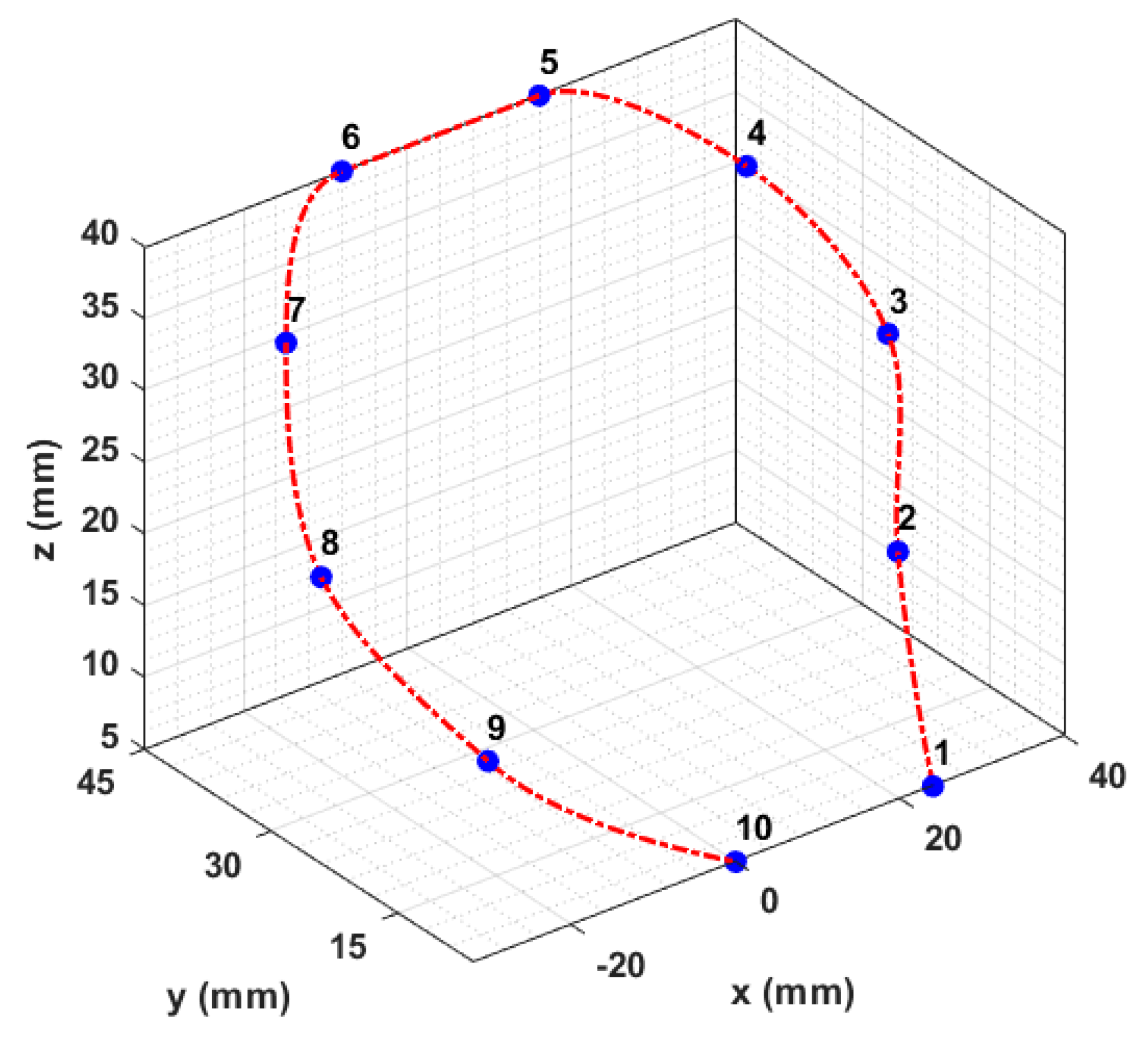

In this research work, a workspace evaluation algorithm of the HSR’s parallel platform has been developed using MATLAB® based on the discretization method. This approach involves the knowledge of the inverse kinematics solutions of the platform when it moves radially along X and Y axes and vertically along the Z axis. The feasible poses of the platform are estimated iteratively within a predetermined subspace. This algorithm begins the iterative process by sub-dividing space through a hollowed cylindrical methodology, in which every point will be validated upon checking the inverse kinematic solutions. The values of Euler angles and are varied between a range of −60 degrees and 60 degrees with a step size of 0.2 for all iterations. The elevation limit for vertical motion in the Z axis was kept at 50 mm. The iterative process computes the pose values for different sets of Euler angles and and elevation in the Z axis. A validation process confirms all potential valid positions. The conditions of validation criteria are:

Leg length feasibility: The solution is to be retained only if the parallel platform’s actuator leg lengths satisfy the length constraint, i.e., .

Joint limits: The pose will be considered when the actuated legs’ orientation relative to spherical joints is within the allowable limit of 60 degrees, keeping in view the limitations of spherical joints [

53].

Collision avoidance: Any pose leading to collisions between top and bottom plates of the parallel platform or excessive actuator crossing should be discarded.

Condition number evaluation: Any pose with a singular Jacobian matrix or extremely high values of condition number should be excluded.

The last step is to view the platform’s workspace by plotting the verified data points as depicted in

Figure 8. This figure denotes the feasible workspace of the HSR’s parallel platform. The process of iterative mapping makes the interpretation of the robot’s kinematic ability clearer. Through the usage of this computational method, a complete description of the achievable workspace is obtained. The approach implemented is an efficient method of examining the reachability and dexterity of the parallel platform of the HSR.

6. Discussion

An 8-DOF design of the HSR has been proposed in this study, which faced a restricted range of motion due to inherent limitations of its parallel platform. To address this issue, a multi-stage design analysis of the platform has been implemented in this research. This analysis covered three different kinds of models and analyses, which helped in identifying the restrictions and constraints of the platform’s design. The multi-stage analysis highlighted serious issues in the HSR’s parallel platform’s initial model and raised the need for optimization of its design based on its geometric and structural parameters. The optimized model was tested for its motion planning capabilities as described in

Section 5. This section provides a detailed discussion on each section of this paper.

6.1. Design Analysis

The first analysis, named kinematic analysis, determined the leg lengths that are required to reach the desired surgical pose. Any deviation in these values may lead to positional inaccuracies and errors in the platform’s performance. The second analysis, termed as geometrical analysis, employed the information from the findings of kinematic analysis and derived a relation for the Jacobian matrix, which not only influences the angular velocity and wrench values of the platform but also plays a huge role in estimating its condition number. The third analysis is singularity analysis, which is governed by the values of the GCN. It involved four test cases obtained by altering the geometric parameters of the platform like joint angles of the upper and lower plates and the radii of both plates. The values of the GCN were recorded when each test case explored 150 different poses based on Latin hypercube sampling (LHS). The results of this analysis, tabulated in

Table 2, indicated higher values of GCN, indicating clear deterioration of the platform’s kinematic conditioning when the design of the platform was more symmetrical. These high GCN values strongly justify the need for the parallel platform’s design optimization in order to improve its performance and maneuverability.

6.2. Comparison of Design Optimization Techniques

This study uses both GA and NSGA-II to optimize the parallel platform of an 8-DOF HSR in order to provide an obvious comparative frame with optimization methodologies that were reported in the existing literature. The pattern search approach given in [

26] is a deterministic derivative-free technique designed to maximize a single global performance index (GPI). While it is efficient for single-objective problems, it cannot account for trade-offs between several performance parameters such as dexterity, stiffness, and effort required by the actuator, and it is prone to converge at local optima. In contrast, the neural network-based optimization reported in [

31] is based on a different paradigm, where the configurations of Stewart platforms are predicted for given tool orientations. Though successful for operational adaptation, this approach is limited to motion-level optimization, does not include structural design, and relies heavily on training data, hence limiting their generalizability and robustness.

On the other hand, the present research tests the exploratory capabilities of GA as well as NSGA-II for design-oriented optimization of the HSR’s parallel platform. GA provides a powerful global search mechanism, which can efficiently search the complex, multimodal design spaces and find near-optimal solutions for a single objective such as GCN improvement. NSGA-II extends this ability by simultaneously optimizing a number of conflicting objectives like dexterity, stiffness, and actuator forces, employing Pareto dominance to maintain a balance between all the objectives. This evolutionary algorithm supports thorough exploration and efficient convergence, providing a resultant design that shows significant improvements in GCN, stiffness, and actuator forces.

In this research, the design optimization of the parallel platform began with the identification of parameters that influence its performance greatly. The deterioration of performance due to the major concern of the higher values of GCN was first attempted to be resolved through GA-based single-objective optimization. This approach significantly reduced the GCN to 1.78 but could not address the issues related to actuator forces and stiffness. The value of norm of actuator forces was high and the stiffness was low for a miniaturized model of the HSR’s platform, as reported in

Table 3c. The purpose of optimizing the design is to obtain a model with an optimal set of all three parameters without compromising any of them. This led to an evolutionary algorithm-based multi-objective optimization approach named NSGA-II. The attributes of this approach like non-dominating sorting, crowding distance, and the concept of elitism introduced faster convergence of results, diversity in the designs, and preservation of the best solutions among each generation. A comparison based on the performance parameters of both GA and NSGA-II is summarized in

Table 7.

A convergence in the results for NSGA-II was noticed around 160 iterations, and it was deduced that the optimal solution of the HSR’s parallel platform has been achieved. The optimization process was also monitored in terms of computational time. The convergence of results at 160 iterations was obtained in 2538 sec with acceptable computational overhead on a 10th generation Intel(R) Core (TM) i5. The results reported in

Table 4a and

Table 5b present the optimized design of the parallel platform, which has a GCN value of 2.21, minimized norm of actuator forces of 7.66 N, and maximized stiffness value of 1339 N/m. From

Figure 7, the values of different Pareto-optimal fronts can be deduced based on the user’s observations and requirements, and the highest values of each parameter can also be determined. The highest values of the GCN, norm of actuator forces, and stiffness are determined to be 6.53, 23 N, and 1475 N/m, respectively. An optimized design offering a good trade-off among performance parameters was selected, with GCN values closer to unity so that the platform tracks and plans the desired trajectories without reaching the singular configurations. Furthermore, these close to unity values of the GCN also have an impact on the feasible range of workspace in which the platform operates, which is determined and depicted in

Figure 8. Other than the reduction of the GCN, another milestone achieved by multi-objective optimization is the maximization of the minimal stiffness values in the workspace of the platform. At singular configurations, the platform not only lost its DOFs but also faced the loss of mechanical stiffness. This issue was catered for by improvement in GCN values, which led to enhanced stiffness within the platform’s workspace. In comparison with GA, the optimized model of NSGA-II had 24 percent more value for the GCN; this is because GA focused on reducing GCN only, which led to overfitting for dexterity at the expense of mechanical robustness, while the goal of NSGA-II was to obtain the best trade-off among all three objectives being considered. Quantitatively, the NSGA-II-based optimization resulted in an approximately 147 percent improvement in stiffness and reduced actuator forces by about 93 percent with respect to the GA design while ensuring an acceptable dexterity. Reduction of the norm of actuator forced was an aim in this optimization, keeping in view the drawbacks of excessive forces that may cause accidental overshoots and tremors, wear and tear of the robot, and thermal buildup in the components. To avoid these issues and make it efficient for soft-tissue interactions, the actuator forces were minimized. After the optimization, the feasible workspace of the platform was analyzed, considering the joints, actuators, and other geometric constraints of the HSR’s parallel platform.

In order to analyze the numerical strength and accuracy of the optimization results of the NSGA-II (

Figure 6), a small-scale analysis of errors was conducted. Pareto-optimal convergence of the five independent optimization runs with the same parameter settings was reviewed. It was found that the standard deviation of the objective at convergence was similar and equal to

, and

percent in GCN, actuator force, and stiffness, respectively, with high precision in the results of the optimization process. The small variations are caused by the stochastic behavior of the crossover and mutation operations, without which the evolutionary algorithms bring random diversity. The fact that there is low dispersion among the runs is confirmation that the algorithm is consistent in converging to the same Pareto front as opposed to local minima that are random. The difference in the solutions does significantly influence engineering values and makes negligible differences in the qualitative trade-offs between objectives. This type of stochastic consistency analysis is consistent with existing methods of uncertainty assessment of multi-objective evolutionary algorithms [

54].

6.3. Workspace of HSR

The workspace assessment in

Section 4 revealed that the optimized design of the parallel platform of the 8-DOF HSR possesses a large and dexterous workspace and can continue to remain mechanically stable and singularity-free. The numerical discretization method enabled accurate mapping of feasible poses and a smooth and continuous workspace with no discontinuities, and this confirms the structural symmetry obtained after optimization. The optimized geometric parameters, especially plate radii and joint orientations, were improved as opposed to pre-optimized settings and offered better reachability in all translational and rotational directions. Workspace evaluation helped in avoiding the singular and collision-prone areas and determining a kinetically stable structure of the platform, resulting in a confined yet practically adequate workspace that could be utilized in surgery. This platform’s workspace is, therefore, an optimized trade-off between optimized conditioning and stiffness, which validates that the NSGA-II optimized design has achieved the improvement of motion performance of the HSR without compromising control of its parallel platform.

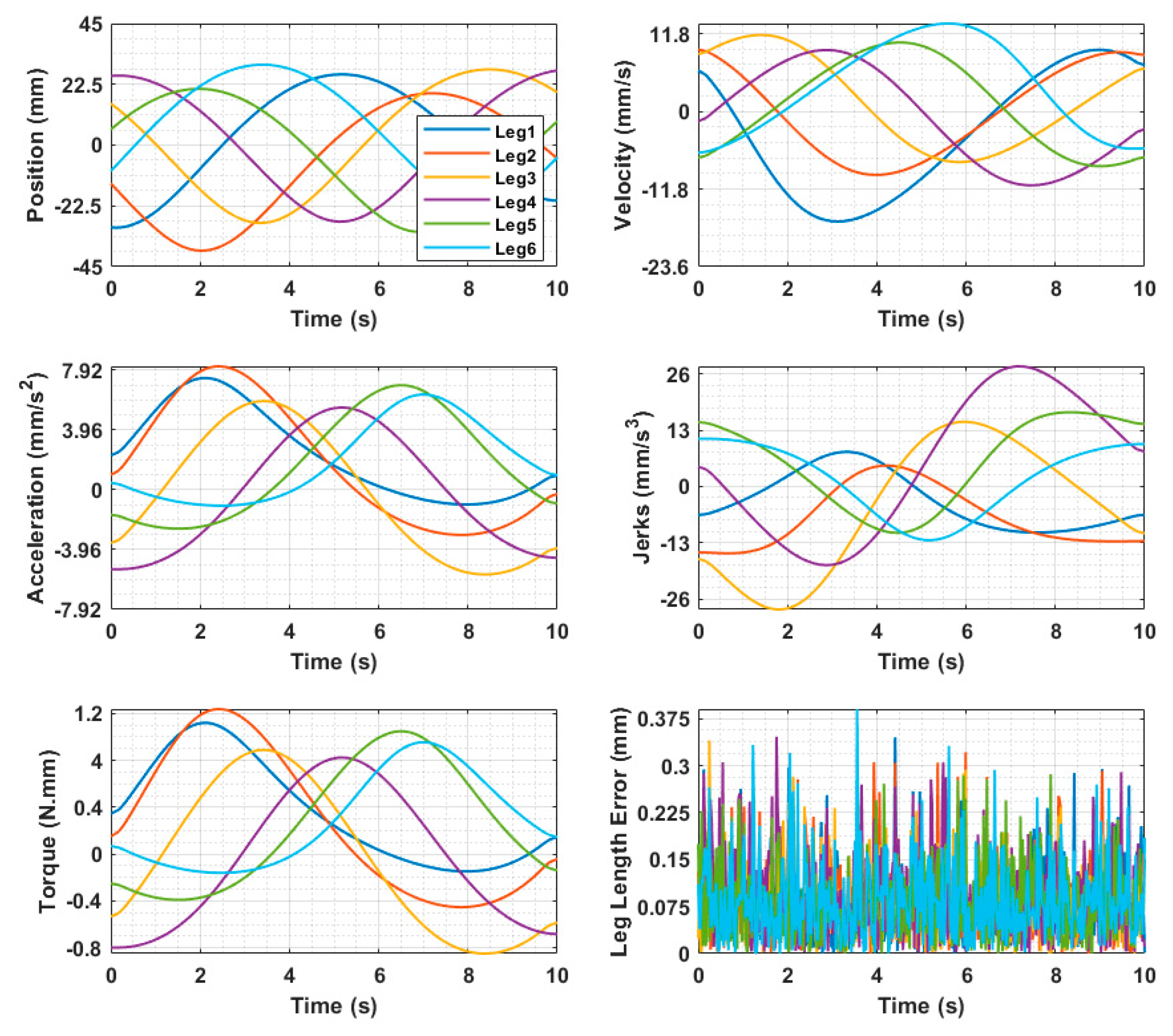

6.4. Motion Planning of HSR

The motion planning assessment in this study shows that the proposed hybrid surgical robot is able to realize both discrete and continuous motion patterns with excessive spatial precision and stable dynamic response. In the case of Trajectory 01, the robot had an average tracking error around 0.07 mm, with a peak deviation smaller than 0.12 mm, which shows that the HSR’s platform has a good ability to reproduce the trajectory of waypoint-based movement. The resulting trajectory velocity and acceleration profiles did not exhibit overshoot and sharp transitions, and the magnitudes of jerk were low, which verified the undesired oscillation-free motion ability of the system for delicate situations in surgery. These characteristics indicate that the optimized parallel platform is appropriate for applications that require a fine positioning and controlled approach maneuver such as needle insertion, target alignment, or reorientation of the tool in close proximity to sensitive anatomic structures.

In the case of the 3D spiral path, where all three spatial axes would need to be coordinated, the optimized parallel platform performed a stable and accurate path, following with an average error of about 0.17 mm and a maximum error limited to 0.375 mm, which is within clinically acceptable limits of a minimally invasive procedure. Despite the increased curvature and dynamic coupling requirements, the velocity, acceleration, and torque curves were controlled; the jerk response was constrained, which showed continuous smooth motion; and mechanical oscillations were not induced. This demonstration confirms the fact that not only is the system capable of dealing with correct point-to-point positioning, but it can also assist in more complex, continuous navigation operations like contour tracking, surface following, or controlled tool sweeping when performing surgery. All these findings affirm that the HSR has the accuracy, stability, and dynamic fluidity to operate safely and accurately in any surgical operation and support its use in neurosurgical and other small-scale operating scenarios where motion accuracy is paramount.