This section provides the evaluation of the efficiency and convergence behaviour of the analyzed extended parametric family of methods. To validate the theoretical results, the performance of the analyzed schemes is compared with several established iterative methods from the literature.

4.3. Computational Efficiency

To objectively compare the performance of the analyzed methods against existing schemes, we utilize the Computational Efficiency Index, denoted

. Unlike the order of convergence, which solely measures error decay, the Computational Efficiency Index acts as a general normalized metric for processing time, allowing for comparisons that are unaffected by the specific machine architecture used. Similar analysis was also provided in [

16] for parametric families (

6) and (

7).

According to the methodology for high-precision arithmetic contexts, the computational efficiency is defined as follows:

where

p is the order of convergence of the method, and

is the total computational cost per iteration. D acts as a normalization factor for the arithmetic cost; for our analysis, we set

To compare the efficiency of the analyzed methods against existing schemes, we establish a computational cost function for a system of nonlinear equations of dimension m. This function accounts for evaluations of elementary functions, linear algebra operations, and elementary vector operations.

The total computational cost is expressed as a weighted sum of function evaluations and algebraic operations, normalized to the cost of a single multiplication product. The cost function is defined as follows:

where the parameters are defined as follows:

is the computational cost of evaluating a single component of .

is the computational cost of evaluating a single component of the Jacobian .

is the aggregated cost of solving linear systems, where is the cost ratio of a division relative to a multiplication.

is the cost of elementary operations, including scalar–vector, vector–vector, and matrix–vector multiplications.

The algebraic cost

depends on the matrix factorization technique. We assume an LU decomposition strategy. Based on standard linear algebra complexities, the cost of one LU decomposition (

) and the resolution of the necessary triangular systems (

) for a system of size

m are given by

Additionally, we explicitly account for the cost of auxiliary operations (

). The costs for scalar–vector (

), vector–vector inner product (

), and matrix–vector (

) multiplications are defined as follows:

By substituting the expressions for and into the method-specific operation counts, we derive the final polynomial cost formulas for the analyzed family (LW, RW, CM) and the comparison methods (SM, SHM, OM).

1. LW and RW

LW and RW require two function evaluations and one Jacobian evaluation. Algebraically, they perform one LU decomposition and two triangular system solutions. The update step involves two vector–vector products and one scalar–vector multiplication (

).

2. Cordero’s Method (CM)

Similar to the previous approaches, this method requires two function evaluations, one Jacobian evaluation, one LU decomposition, and two triangular solutions. However, the update formula applies distinct weights to the function vectors, requiring an additional scalar–vector multiplication (

).

3. Singh’s Method (SM)

This method requires three function evaluations and one Jacobian evaluation. It performs one LU decomposition and three triangular system solutions.

4. Sharma’s Method (SHM)

Sharma’s Method evaluates the Jacobian at two points and performs one function evaluation. It requires two LU decompositions and three triangular solutions. The method also involves matrix–algebraic approximations requiring two matrix–vector multiplications and four scalar–vector multiplications (

).

5. Ostrowski’s Method (OM)

Ostrowski’s method requires two function evaluations and one Jacobian. It also involves a divided difference that contains m(m − 1) additional function evaluations.

To accurately assess the efficiency of the analyzed iterative methods, we evaluated the computational cost of elementary functions using arbitrary-precision arithmetic. Unlike standard floating-point arithmetic, which is heavily optimized by hardware, arbitrary-precision calculations provide a hardware-independent benchmark that reflects the algorithmic complexity of the operations.

The costs were estimated using the

python-flint library with a precision of 1000 decimal digits. The computational cost

C of each function is defined relative to the time required for a single multiplication operation (

):

where

is the average execution time of the function

f and

is the average execution time of one multiplication.

Table 2 presents the estimated costs used in this study.

As shown in the table, the cost of transcendental functions (e.g., , ) increases significantly at high precision compared to basic arithmetic operations. This weighting is crucial for calculating , as it accounts for the heavy penalty of evaluating complex nonlinear functions in high-precision environments.

To test the applicability and robustness of the analyzed iterative methods, we have prepared a diverse set of numerical examples spanning low- to high-dimensional systems. The first two examples are selected from [

16] to benchmark the implementation of the method against existing schemes in the article.

4.3.1. Example 1: Exponential Trigonometric System [16]

We consider the following system of nonlinear equations of dimension two:

For this problem, the initial estimate

is used. The approximate solution for this system is

, and the cost parameters are

.

The results are presented in

Table 3. The columns report the number of iterations (

k) required to meet the stopping criterion, the difference between two last iteratates (

), the residual norm (

), the Computational Order of Convergence (COC), computational efficiency (CE), and the CPU time. For all examples, we set

(see

Table 2).

The analyzed methods (RW and LW) demonstrate superior efficiency, converging in only five iterations compared to six for all other methods. This faster convergence is reflected in the CPU time, with LW being the fastest (0.00594 s). The computational efficiency analysis reveals that the analyzed methods, LW and RW, achieve the highest efficiency index. Although SHM and CM achieve extremely small residual norms (e.g., ), this level of precision required an additional iteration, whereas the analyzed methods achieved sufficient accuracy () one step earlier, satisfying the tolerance more quickly. CM requires six iterations but remains relatively fast. All methods exhibit a COC of approximately 4, confirming their theoretical fourth-order convergence.

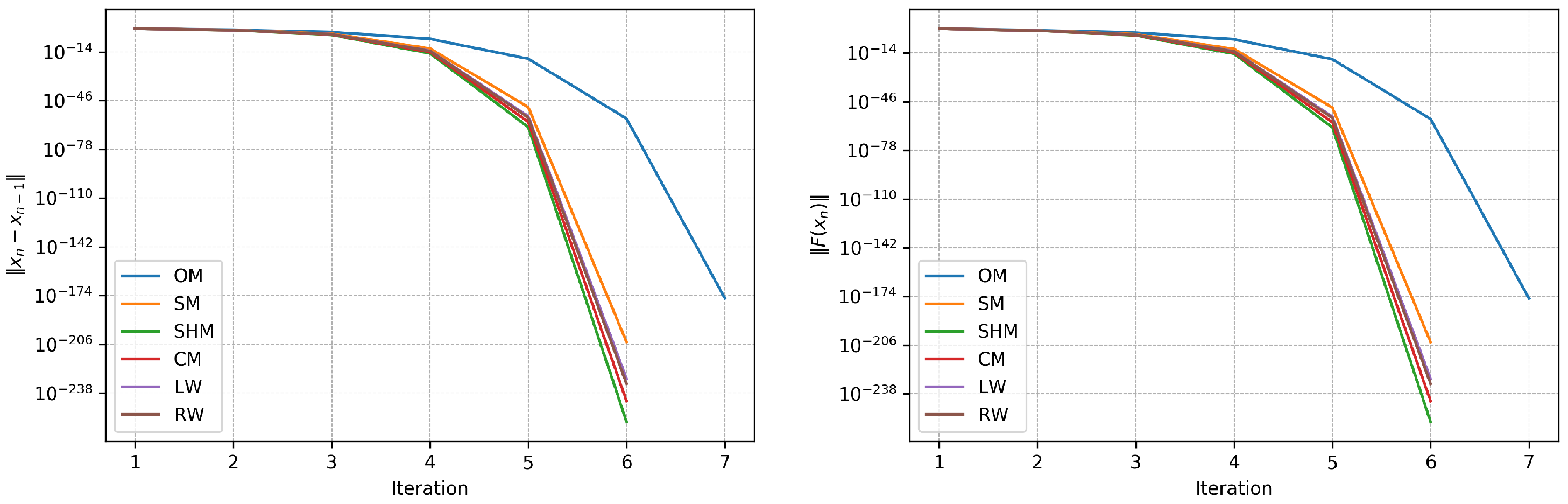

Figure 1 illustrates the convergence behaviour of the iterative methods for Example 1 by plotting the error norms versus the iteration number

k. The plots display the logarithm of the step norm,

, and the logarithm of the residual norm,

, against the iteration number. It is evident that the analyzed methods, LW (purple) and RW (brown), exhibit the fastest rate of decay (they coincide) and reach the required machine precision levels by the fifth iteration. In contrast, other algorithms require six iterations to converge, but all of them, except OM, achieve quite high precision. Overall, both plots corroborate the numerical results in

Table 3, validating the enhanced performance of the analyzed methods.

4.3.2. Example 2: Trigonometric System [16]

The following system of nonlinear equations is considered:

For this experiment,

is selected, and the initial estimate

is used. The parameters needed for cost evaluation are

. Different algorithms yield different solutions.

Table 4 summarizes the performance of several iterative methods for Example 2. The Rational Weight (RW) method demonstrates the highest efficiency, converging in seven iterations with the lowest CPU time of 0.0281 seconds. The Sharma et al. Method (SHM) requires nine iterations and a longer CPU time (0.0795 s) than RW. The Linear Weight (LW) and Cordero’s Method (CM) converge in 12 and 14 iterations, respectively, with moderate CPU times. Ostrowski’s Method (OM) and Sharma’s Method (SM) are notably slower, requiring 31 and 47 iterations, respectively, and significantly more computational time. For this medium-sized system (

), CM, LW, and RW achieve efficiency scores nearly double that of Sharma’s Method and significantly exceeding Ostrowski’s Method. All methods achieve a computational order of convergence (COC) of 4.0000, consistent with their theoretical fourth-order convergence.

Figure 2 presents the overall convergence rate for all methods in Example 2. The RW method exhibits the fastest decay, confirming its rapid convergence. SHM demonstrates a similar process, while OM and SM display significantly slower convergence.

4.3.3. Example 3: High-Dimensional Cyclic System [9]

To evaluate the method on large-scale problems, the following cyclic system is considered:

A dimension of

is selected, with the initial approximation

and cost parameters

.

The numerical results for Example 3, presented in

Table 5, indicate that most methods (SM, SHM, CM, LW, RW) converge in six iterations, while Ostrowski’s Method (OM) requires seven. Cordero’s Method (CM) and the Rational Weight (RW) method are the most efficient in terms of CPU time, taking approximately 0.46 seconds, whereas SHM is significantly slower at 14.9 seconds. In the high-dimensional case, the efficiency gap widens drastically; the analyzed methods exhibit efficiency indices approximately twice as large as those of Ostrowski’s and Sharma’s Methods (

vs

), highlighting the critical benefit of minimizing matrix factorizations in large-scale problems. All methods exhibit a computational order of convergence of 4.0000, validating their theoretical properties on this large-scale problem. In

Figure 3, most methods follow a similar rapid decay trajectory, with OM lagging slightly behind by requiring an additional step to reach the same precision.

4.5. Example 5: Nonlinear Integral Equation [20]

To evaluate the robustness of the analyzed methods on high-dimensional problems derived from real-world applications, we consider the following integral equation on the interval

:

The equation is discretized using a uniform grid with

m subintervals and step size

, with nodes defined as

for

. The integral is approximated using the trapezoidal rule with weights

, and

for

. This discretization results in a system of nonlinear equations given by

For this numerical test, we select a large-scale dimension of

and use the initial guess

. The convergence behavior is compared against the reference solution

. The numerical results, including error norms at each iteration and total CPU time, are summarized in

Table 6. This experiment shows how many iterations each method requires to achieve accuracy

.

The results presented in

Table 6 demonstrate the distinct advantages of the analyzed parametric family methods (LW and RW) in solving high-dimensional systems (

). Both LW and RW converge rapidly, satisfying the stopping criterion within only three iterations. In contrast, Cordero’s Method (CM) requires four iterations, while Ostrowski’s Method (OM) exhibits instability in the early stages, indicated by an increase in error at the second iteration, and requires six iterations to converge.

In terms of CPU time, the Rational Weight (RW) and Linear Weight (LW) methods are the fastest, with execution times of approximately s and s, respectively. While Sharma’s Method (SHM) also converges in three iterations, it is computationally expensive, requiring s, which is more than four times the cost of the RW method. This confirms that the analyzed family offers an optimal balance between low iteration count and low computational cost per step for large-scale integral equations.

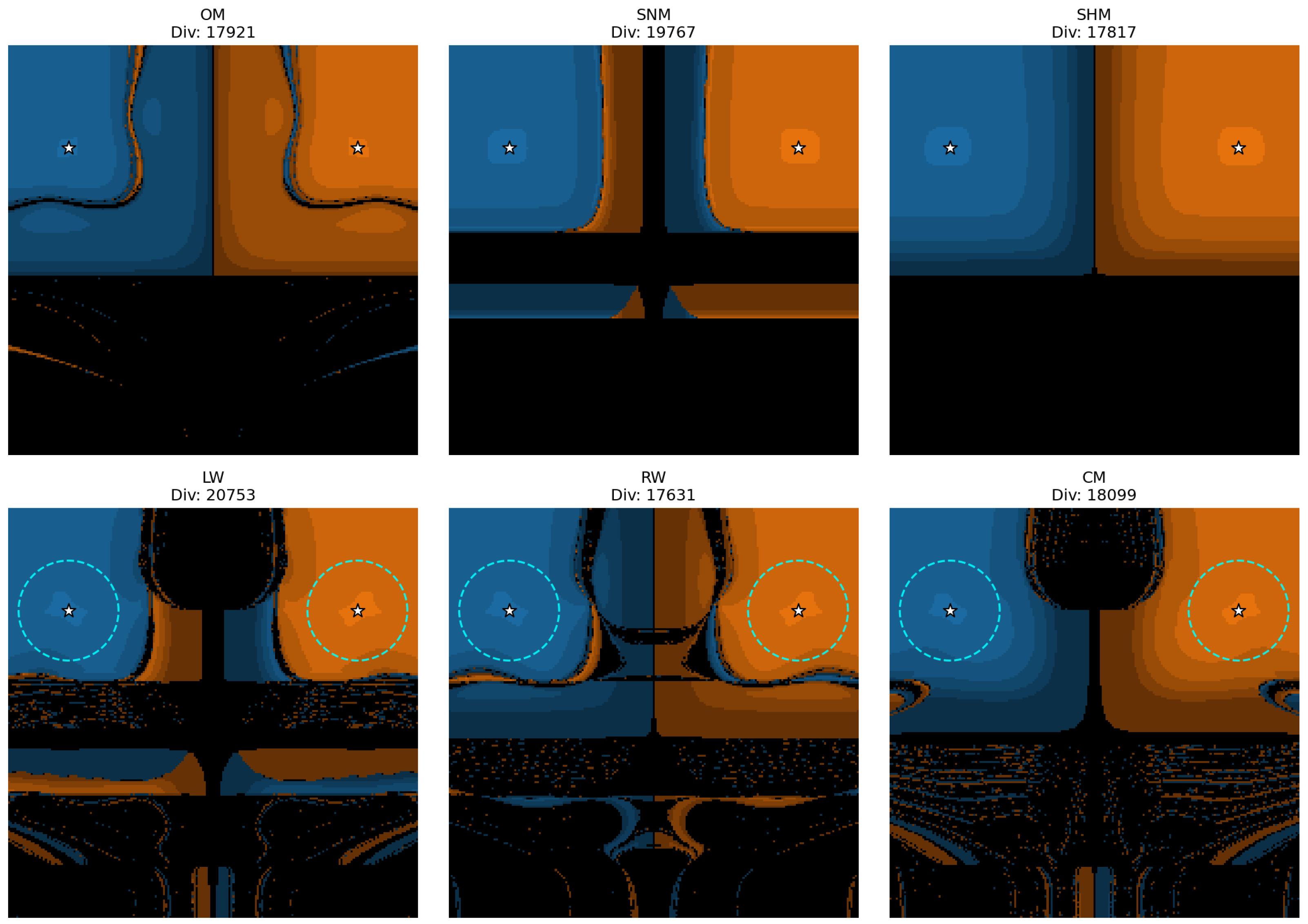

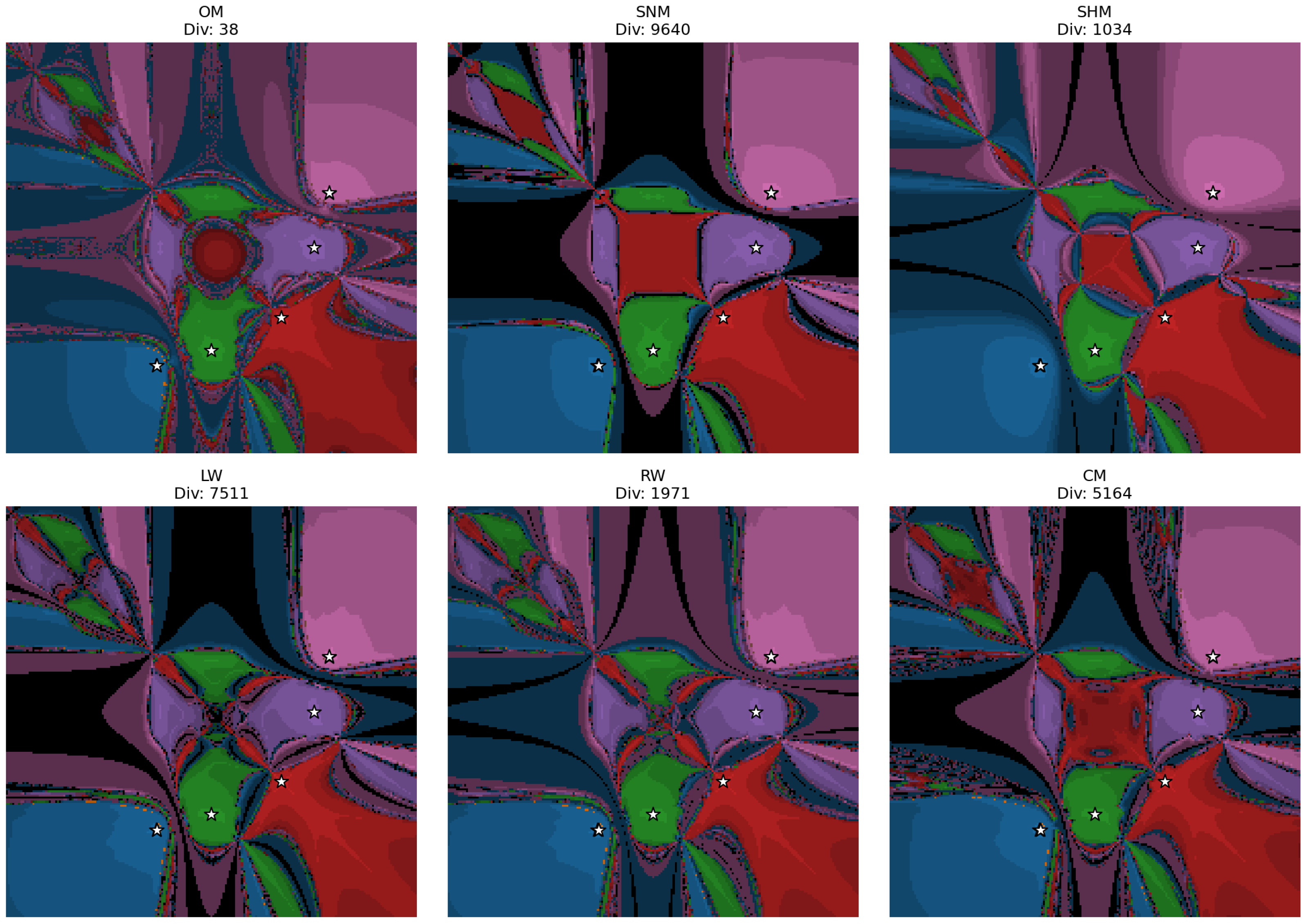

4.6. Basins of Attraction Analysis

The dynamical behavior of the iterative methods (

3) is analyzed by generating basins of attraction. This visualization technique enables assessment of the method’s stability and sensitivity to the choice of initial guess. The

basin of attraction of a root

is defined as the set of all initial points

in a domain

D that converge to

under the iterative mapping. If an initial point fails to converge to any root within a specified maximum number of iterations, it is considered divergent.

To generate these basins, we define a mesh of points within a rectangular domain . Each point is used as an initial guess . If the sequence generated by the iterative method converges to a root , the starting point is colored according to that specific root. To provide further insight into the computational cost, the color intensity is scaled based on the number of iterations required: brighter colors indicate faster convergence (fewer iterations). Black regions indicate points that diverge or fail to converge within the maximum iteration limit.

For these visual simulations, the stopping criterion is set to or a maximum of 50 iterations. The basins are examined for three nonlinear systems:

- 1.

System A:

- 2.

System B:

- 3.

System C:

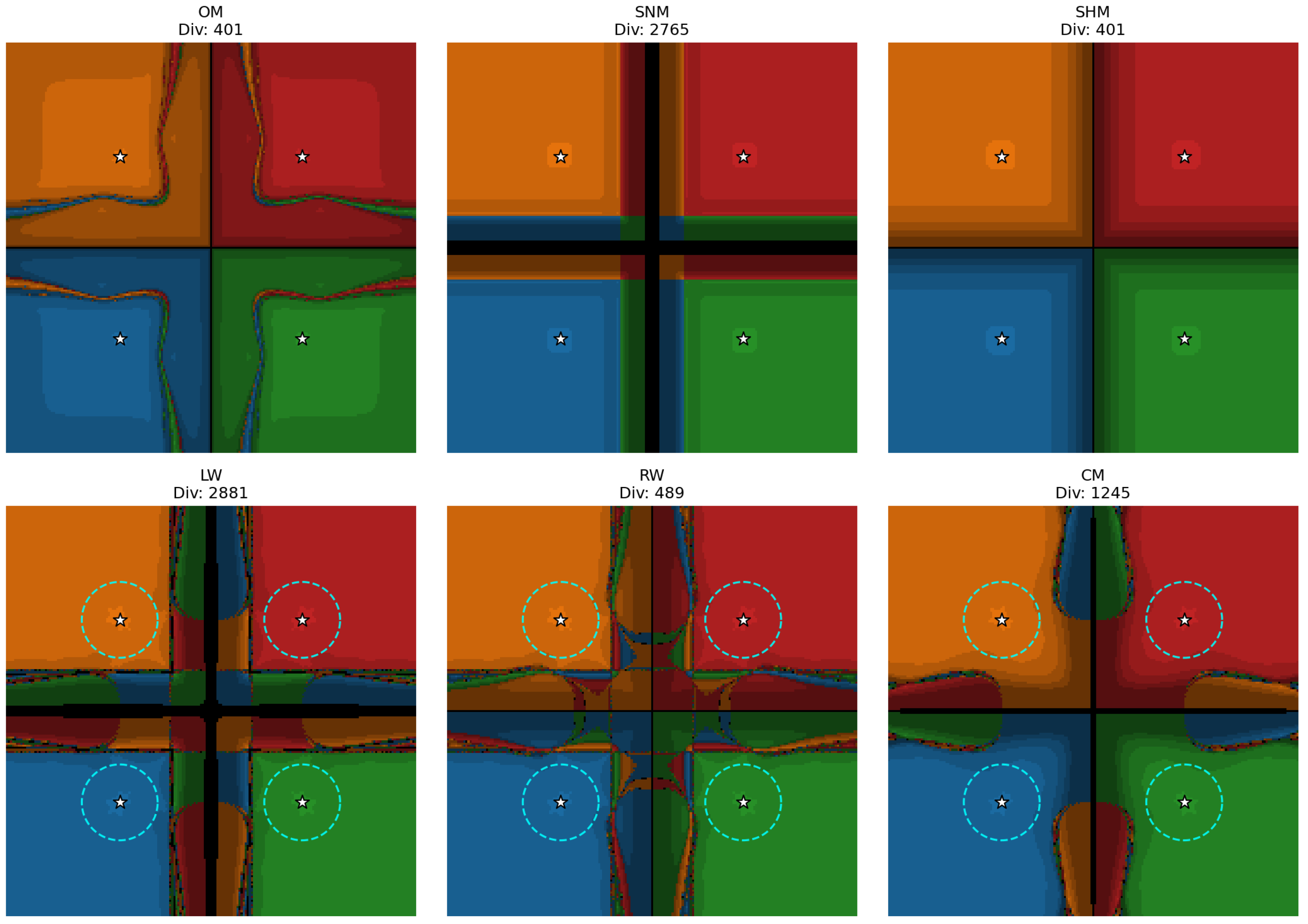

To provide a theoretical verification of the stability regions observed in the basins of attraction, we calculated the precise radii of convergence for Systems A, B, and C. For the methods LW, RW, and CM, the parameters p and q utilized in the local convergence analysis (Condition (H6)) are determined by the limit behavior of the weight functions at the solution, resulting in and .

The bounding functions and were determined as linear functions satisfying the generalized continuity conditions and . In our analysis, we selected , where L is the constant. A is selected as . While it is theoretically possible to find a smaller for (since it is restricted to paths originating from ), using the global constant L provides a rigorous sufficient condition for convergence that holds throughout the entire domain.

The calculated radii are summarized in

Table 7. A key observation is the distinction between the polynomial systems:

Systems A and C. These systems consist of quadratic equations where the second Fréchet derivative is constant. Due to the geometric symmetry of the roots, the norm of the inverse Jacobian is identical for all solutions. Consequently, the constant L and the resulting convergence radius s are the same for every root.

System B. This system involves cubic equations, meaning the second derivative changes with x. Furthermore, the roots are not symmetrically distributed. For instance, at the integer root , the Jacobian matrix contains a zero on the diagonal, leading to a larger norm compared to other roots. This increases the constant L and results in a significantly smaller theoretical radius () compared to the more stable roots ().

Figure 4 shows the basins for System A. In this visualization, the theoretical radius of convergence (

), marked by cyan dashed circles for the analyzed family, is clearly visible and fully contained within the stable regions. The stability is quantitatively confirmed by the low divergence counts (Div). The Rational Weight (RW) method exhibits excellent stability with only

divergent points (out of 40,401), which is comparable to Ostrowski’s Method (

) and significantly better than the Linear Weight (LW) method (

). While both RW and OM are stable, RW displays larger bright areas, indicating a faster rate of convergence. The analyzed methods (LW, RW, CM) exhibit similar morphological shapes, suggesting consistent dynamical behavior across the parametric family.

Table 7.

Convergence bounding functions and calculated radii for Systems A, B, and C (Methods: LW, RW, CM with ).

Table 7.

Convergence bounding functions and calculated radii for Systems A, B, and C (Methods: LW, RW, CM with ).

| Problem | Solution Vector | | | | Radius s |

|---|

| System A | All 4 roots | | 0.5963 | 0.3703 | 0.3703 |

| System B | Root 1 | | 0.0329 | 0.0204 | 0.0204 |

| Root 2 | | 0.0176 | 0.0109 | 0.0109 |

| Root 3 | | 0.0307 | 0.0191 | 0.0191 |

| Root 4 | | 0.0177 | 0.0110 | 0.0110 |

| Root 5 | | 0.0331 | 0.0205 | 0.0205 |

| System C | All 2 roots | | 0.7858 | 0.4879 | 0.4879 |

Figure 5 presents the results for System B. This system poses a unique challenge with fivw roots and the high constant

L, resulting in a very small theoretical radius of convergence (

). Consequently, the cyan radius circles are not visible at this scale. Despite this, the actual basins are extensive. The RW method demonstrates superior stability among the analyzed schemes, significantly reducing the divergence area (

) compared to Singh’s Method (

) and Cordero’s Method (

). Although OM achieves the lowest divergence (

), the analyzed RW method exhibits larger areas of high brightness, implying faster convergence speed. This highlights a trade-off where RW offers competitive stability with enhanced speed.

Figure 6 illustrates the basins for System C, which is computationally the most difficult due to the presence of extensive divergent regions across all methods. OM and SNM exhibit narrow corridors of convergence surrounded by significant chaotic boundaries. In contrast, the analyzed methods LW and RW display wider, more uniform basins around the roots, with minimal chaotic interference. The theoretical stability circles (

) are clearly distinguishable and verify that the immediate neighborhood of the roots is safe. Numerical metrics confirm that the divergence count is lower for the Rational Weight method (Div = 17,631) compared to LW (Div = 20,753) and SNM (Div = 19,767). The analyzed methods (LW, RW, and CM) also appear slightly brighter and maintain similar basin shapes, whereas the comparison methods do not exhibit this common topology.

To complement the visual analysis of the basins of attraction, we computed numerical stability metrics over a

grid (

total points).

Table 8 reports the Stability Index (

), defined as the percentage of initial guesses that successfully converged to any root, the average number of iterations (

) for these converged points, and the total count of divergent points (

).

The results indicate clear distinctions in robustness across the systems:

System A. This system is well behaved for most methods. Ostrowski’s Method (OM) and Sharma’s Method (SHM) exhibit the highest stability () with minimal divergence (). Among the analyzed family, the Rational Weight (RW) method performs best, achieving stability, which is comparable to the optimal methods and significantly more robust than Linear Weight (LW) at .

System B. This system presents a greater challenge due to its cubic nonlinearity. While OM achieves near-perfect stability (), the analyzed RW method demonstrates strong performance with stability, significantly outperforming Singh’s Method (SNM) which drops to . The LW method shows moderate instability here (), confirming the theoretical sensitivity observed in the radius of convergence analysis.

System C. This system proves to be the most difficult for all iterative schemes, likely due to the geometry of the solution space causing the Jacobian to become singular near the coordinate axes. All methods struggle to exceed stability. However, the RW method again proves to be the most robust of the analyzed family, achieving the highest stability index () of all tested methods, effectively minimizing the chaotic regions compared to LW ().

Overall, the Rational Weight (RW) method consistently provides the best trade-off between stability and convergence speed within the analyzed parametric family, often rivaling established methods like OM and SHM.

Figure 6.

Basins of attraction for System C. The roots are marked with white stars. Starting the iterative process from a point within a region of a specific color leads to convergence to the corresponding root. The cyan dashed circles indicate the theoretical radius of convergence . Black regions indicate divergence (Div).

Figure 6.

Basins of attraction for System C. The roots are marked with white stars. Starting the iterative process from a point within a region of a specific color leads to convergence to the corresponding root. The cyan dashed circles indicate the theoretical radius of convergence . Black regions indicate divergence (Div).

Table 8.

Numerical stability metrics for Systems A, B, and C. : Stability Index (percentage of converged points); : Average iterations per converged point; : Number of divergent points (out of 40,401 total grid points).

Table 8.

Numerical stability metrics for Systems A, B, and C. : Stability Index (percentage of converged points); : Average iterations per converged point; : Number of divergent points (out of 40,401 total grid points).

| System | Method | (%) | | |

|---|

| System A | OM | 99.01 | 3.39 | 401 |

| SNM | 93.16 | 3.39 | 2765 |

| SHM | 99.01 | 2.94 | 401 |

| LW | 92.87 | 4.19 | 2881 |

| RW | 98.79 | 4.06 | 489 |

| CM | 96.92 | 3.79 | 1245 |

| System B | OM | 99.91 | 5.53 | 38 |

| SNM | 76.14 | 5.31 | 9640 |

| SHM | 97.44 | 5.59 | 1034 |

| LW | 81.41 | 6.19 | 7511 |

| RW | 95.12 | 7.17 | 1971 |

| CM | 87.22 | 6.67 | 5164 |

| System C | OM | 55.64 | 3.57 | 17,921 |

| SNM | 51.07 | 4.22 | 19,767 |

| SHM | 55.90 | 3.43 | 17,817 |

| LW | 48.63 | 5.19 | 20,753 |

| RW | 56.36 | 4.74 | 17,631 |

| CM | 55.20 | 5.82 | 18,099 |

Across all three examples, OM is the most stable method, but it has fewer bright areas than the parametric family, indicating slightly slower convergence. The RW method exhibits larger bright areas and fewer divergent points, representing the best trade-off between speed and stability. Additionally, the methods RW, LW, and CM display similar shapes across all examples.