1. Introduction

Recent years have seen substantial advances in the theory and methodology of high- and infinite-dimensional Bayesian statistics, driven by the increasing need to model complex structures in modern data. A broad overview of these developments is provided by [

1], which surveys contemporary approaches to Bayesian inference in infinite-dimensional parameter spaces and highlights both theoretical progress and emerging applications. Foundational contributions in this area are deeply rooted in nonparametric Bayesian inference, particularly in the rigorous asymptotic framework developed by [

2]. Their monograph establishes the basic tools for analyzing posterior behavior in infinite-dimensional settings, with emphasis on convergence rates, concentration phenomena, and constructive prior modeling. A novel Bayesian model to handle heterogeneous data with outliers by using a two-component mixture of geometric distributions with a censoring scheme has been proposed in [

3], and Bayesian estimation in life-testing (reliability) studies, where the lifetime model is a multi-component geometric distribution and the data are censored under a given scheme, has been investigated in [

4].

A key line of research within nonparametric Bayesian analysis concerns Gaussian process priors, which naturally give rise to infinite-dimensional posterior distributions. Ref. [

5] derives sharp posterior contraction rates for Gaussian process priors under a variety of smoothness assumptions, thereby offering insight into the adaptability and theoretical guarantees of such priors. Complementing these results, ref. [

6] investigates Bayesian inference for high-dimensional nonstationary Gaussian processes, demonstrating how these models can accommodate spatially varying features in practical applications.

From a frequentist perspective, ref. [

7] studies confidence bands in nonparametric density estimation, providing tools that parallel Bayesian uncertainty quantification and shedding light on the interplay between empirical processes and infinite-dimensional parameter spaces. Related geometric aspects of infinite-dimensional analysis are explored in [

8], which characterizes surface measures in infinite-dimensional Banach spaces, offering insights relevant to both stochastic analysis and the geometry underlying infinite-dimensional Bayesian models.

The notion of prevalence plays a fundamental role in understanding “large” or “generic” behavior in infinite-dimensional spaces. Ref. [

9] introduces prevalence as an infinite-dimensional analogue of “almost everywhere” that is invariant under translation, offering a conceptually robust measure-theoretic framework for discussing typical behavior in infinite-dimensional Bayesian settings.

A separate but increasingly influential body of work highlights challenges and potential pathologies in Bayesian inference when models are misspecified or data dependencies are ignored. Ref. [

10] analyzes the dynamics of Bayesian updating under model misspecification and dependent data, demonstrating that posterior behavior can deviate substantially from classical expectations under standard assumptions. Ref. [

11] further emphasizes the vulnerability of Bayesian inference in high and infinite-dimensional contexts, showing that even minimal perturbations of the model or prior can lead to dramatic changes in posterior conclusions.

This growing body of work forms the basis for contemporary research that seeks to develop reliable, flexible, and computationally tractable Bayesian methods in increasingly complex and high-dimensional settings.

In this work, we investigate stochastic processes taking values in infinite-dimensional normed spaces, where the available information is represented by the -algebra generated by a finite or countable sequence of random variables. This -algebra is properly contained in the initial -algebra of the underlying probability space. As a consequence, for any event that does not belong to the conditioning -algebra, the corresponding conditional probability cannot be defined in the standard axiomatic sense, since it fails to be measurable with respect to the conditioning -algebra.

In the classical framework [

12], conditional probabilities are defined as measurable functions with respect to a conditioning

-algebra, ensuring consistency with the axioms of probability. However, when dealing with stochastic processes in infinite-dimensional settings, such as in functional analysis or random fields in Banach or Hilbert spaces, this assumption becomes restrictive. The interplay between topology, norm equivalence, and

-algebraic measurability introduces structural limitations that prevent the direct extension of classical conditional probability.

To address these limitations, we propose an extension of the coherent conditioning model based on Hausdorff measures ([

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]) and its properties ([

18,

19]. The key idea relies on the fact that, in infinite-dimensional normed vector spaces, not all norms are equivalent. Consequently, the associated metric structures induce different Hausdorff dimensions for the same events. Each conditioned event is thus associated with a set of possible Hausdorff dimensions

, and the family of corresponding Hausdorff outer measures is used to define conditional probabilities in different metric spaces. In this approach, the fact that an event is considered rare is not an intrinsic property of the event itself but rather depends on the conditioning event, that is, on the information available and on the particular metric space being considered. The role of unexpected or rare events—represented by events with zero conditional probability—has been fundamental in the mathematical representation of the unconscious activity of the human brain ([

20,

21]). The model and rare events have been investigated also by considering other fractal measures ([

22,

23,

24]). This approach allows the definition of conditional probability to depend explicitly on the underlying geometric and metric structure of the space. As a result, the notion of rare or unexpected events, those of zero probability given a certain conditioning event, becomes relative to the chosen metric and the corresponding Hausdorff dimensional measure. Such a framework provides a richer and more flexible foundation for understanding conditional structures in stochastic processes on infinite-dimensional spaces, with potential applications in infinite-dimensional Bayesian inference.

2. Motivation

In this section, it is highlighted how the axiomatic definition of conditional expectation, based on the notion of Radon–Nikodym, can lead to an incoherent posterior, because the property of being measurable with respect to the -field of the conditioning variables, which is required for the axiomatic definition of expectation, contradicts a necessary condition for coherence.

Let

be a partition of

in a metric space

A bounded random variable is a function

, and

is the class of all bounded random variables defined on

; for every

, denote by

the restriction of

X to

B and by sup(

the supremum value that

X assumes on

B. The class of all bounded random variables

is

. The indicator function

of an event

, i.e.,

if

and

if

. For every

, coherent upper conditional expectations or previsions

are functionals defined on

[

25].

Definition 1. Coherent upper conditional previsions are functionals defined on , such that the following axioms of coherence hold for every X and Y in and every strictly positive constant λ:

- (1)

;

- (2)

(positive homogeneity);

- (3)

(subadditivity).

Assume that

is a coherent upper conditional prevision on a linear space

. Its conjugate coherent lower conditional prevision is defined through the conjugacy relation

Whenever, for every

, we have

the functional

is called a coherent

linear conditional prevision. If, in addition,

, then

is a linear, positive, and positively homogeneous functional in the sense of de Finetti [

26,

27] and Walley [

25] (Corollary 2.8.5).

From axioms (1)–(3) and the conjugacy property, it follows that

hence,

In [

25], the functionals

defined for

and

, satisfying axioms (1)–(3), and such that

, are termed

separately coherent.

The unconditional coherent upper prevision is obtained as the special case . Coherent upper conditional probabilities arise when only -valued random variables are considered.

Definition 2. Given a partition and a random variable , a coherent upper conditional prevision is a random variable on taking the value for .

Definition 3. A bounded random variable is called -measurable (or measurable with respect to the partition ) if it is constant on each atom of the partition.

The following necessary condition for coherence holds [

25] (p. 292).

Proposition 1. If is a coherent linear prevision for every B belonging to a partition of , thenfor all -measurable random variables . Coherent Conditional Prevision and Conditional Expectation

In the axiomatic approach [

12] (Section 34), conditional expectation with respect to a conditioning

-field is defined via the Radon–Nikodym derivative.

Let

and

be two

-fields on

with

, and let

X be a positive and integrable random variable. Let

P be a probability measure on

, and define a measure

on

by

Then,

is finite and absolutely continuous with respect to

; therefore, there exists a non-negative,

-measurable, and integrable function defined on

-the Radon–Nikodym derivative—denoted

, such that

Although the Radon–Nikodym derivative is non-negative, this is no restriction for defining the conditional expectation of an arbitrary integrable random variable. Indeed, for

X not necessarily non-negative, we write

, where

and define

This function satisfies the usual properties and is unique up to

P-null sets; it is a version of the conditional expectation.

The next theorem, proven in [

28], shows that whenever the

-field

is properly contained in

and contains all singletons of

, then the conditional prevision defined by the Radon–Nikodym derivative need not be coherent. This failure stems from the fact that one of the defining properties of the Radon–Nikodym conditional expectation is

-measurability, which contradicts the necessary condition for the coherence of a linear conditional prevision stated in Proposition 1.

Theorem 1. Let , and let F and G be two σ-field of subsets of such that G is properly contained in F, and it contains all singletons of . Let B be the partition of singletons, and let X be the indicator function of an event A belonging to . If we define the conditional prevision equal to the Radon–Nikodym derivative with probability 1, that is,except on a subset N of of P-measure zero, then the conditional prevision is not coherent. 3. Mathematical Preliminaries

In this section, we study the phenomenon described in Theorem 1, namely the possible incoherence of the axiomatically defined conditional expectation obtained from the Radon–Nikodym derivative. More precisely, when conditioning on a -field , the value of the conditional expectation of an event A may differ from its indicator function , despite the fact that coherence would require the equality for all -measurable indicator functions. This mismatch reveals that Radon–Nikodym conditional expectations may fail to be coherent linear conditional previsions. We examine this issue in depth in the framework of infinite-dimensional stochastic processes, where such inconsistencies arise naturally due to the rich structure of the underlying filtrations.

3.1. Infinite Dimensional Normed Vector Spaces

Let

be a metric space. The metric

d induces a topology

on

, defined by

where

denotes the open ball of radius

r centered at

x.

The

Borel σ-field on the metric space

is the

-field generated by this topology:

In other words, is the smallest -field containing all open sets of the topology induced by the metric d. The sets in are called Borel sets. Let be a probability space, and let be a random variable. The random variable X induces a probability measure on the measurable space , where is the Borel -algebra on .

The induced probability measure

is defined by

This measure describes the distribution of

X and allows us to study

X as a measurable function independent of the original probability space

.

The space of real-valued random variables on

can be endowed with a vector space structure. In particular, if we consider the space

this becomes a Hilbert space when equipped with the inner product

Thus, probability spaces give rise to vector spaces (in particular, Hilbert spaces), where random variables can be added, scaled, and compared via inner products and norms:

A metric can be naturally defined using a norm. Let

V be a vector space over

or

, and let

be a norm on

V. Then, the function

defines a metric on

V, called the

metric induced by the norm.

Therefore, any normed vector space naturally gives rise to a metric space , where .

3.2. Equivalence of Norms

Let and be two metric spaces defined on the same set X.

Definition 4. Two metrics and on X are said to be topologically equivalent if they generate the same topology on X. That is, a set is open in if and only if it is open in .

Definition 5. Two metrics and on X are said to be bi-Lipschitz equivalent if there exists a constant such that for all , Bi-Lipschitz equivalence implies topological equivalence, but the converse is not true in general. That is, two metrics can be topologically equivalent without being bi-Lipschitz equivalent.

Example 1. Consider , and define the metricsThese metrics are topologically equivalent, as they generate the same open sets. However, they are not bi-Lipschitz equivalent: the ratio tends to 0 as ; so, no global Lipschitz bounds exist in both directions. In a finite-dimensional vector space, all norms are equivalent. That is, given any two norms

and

on

, there exist constants

such that for all

,

This equivalence implies that the metrics induced by these norms, defined by

and

, generate the same topology on

.

Consequently, open sets, closed sets, convergence of sequences, and continuity of functions are the same with respect to both metrics. This is a fundamental result in analysis, ensuring that topological properties in finite-dimensional normed spaces do not depend on the particular choice of norm.

Example 2. Consider the Euclidean norm and the maximum norm on . These norms are equivalent, and therefore, the metric spaces and have the same topological structure.

However, in infinite-dimensional spaces, there exist norms that are not equivalent and, hence, define different topologies.

For example, consider the space , the set of continuous real-valued functions on the interval . It can be equipped with different norms, such as

The supremum norm:

The norm:

These norms are not equivalent. For instance, one can construct a sequence of functions that converges to zero in the norm but not in the supremum norm.

In general topology and functional analysis, two metrics and on a set X are called equivalent if they generate the same topology. This means that the convergence of sequences, continuity of functions, and openness of sets are the same under both metrics.

In infinite-dimensional spaces, however, in some restricted infinite-dimensional settings, equivalent metrics can still be constructed. Below are some examples.

Definition 6. The space is the set of all infinite sequences of real or complex numberssuch that the series of absolute values is convergent:Formally, we write The norm on , called the norm, is defined as is a normed vector space over or , it is a Banach space (i.e., it is complete with respect to the norm), and it is infinite-dimensional.

Example 3. Let denote the space of sequences with only finitely many non-zero entries. On this space, consider the following norms:Since vectors in have finite support, all the above norms are finite and induce equivalent metrics. That is, the topologies defined by the metrics are the same. Example 4. Consider the space . Define two norms on X byThese norms are equivalent on X, since each bounds the other up to a constant factor. Therefore, the metrics they induce are also equivalent. Example 5. Let be the space of continuous real-valued functions on the interval . This space is commonly equipped with the uniform norm:An alternative (bounded) metric that induces the same topology isThough this metric is not induced by a norm, it is equivalent to the one defined by , in the sense that both generate the same topology on . These examples illustrate that while infinite-dimensional spaces may not admit globally equivalent norms in general (e.g., and are not isomorphic), it is still possible to construct equivalent metrics in restricted contexts.

3.3. Conditional Probability and Measurability in Infinite-Dimensional Spaces

Definition 7. Let be a normed vector space over (or ), and let be a probability space. A stochastic process taking values in V is a family of V-valued random variableswhere is an index set, typically representing time, and for each , the map is a measurable function. That is, for every , the function is such that, for any Borel set , the preimage , meaning is -measurable with respect to the Borel -algebra on V.

If V is a Banach space (i.e., a complete normed vector space), then is called a Banach space-valued stochastic process.

In the context of stochastic processes defined on infinite-dimensional spaces, conditional probability presents unique challenges. A key issue arises when the -algebra with respect to which we condition is generated by a topology that is strictly weaker than the topology of the ambient space.

Let be a probability space, and let be a stochastic process taking values in a product space , where T is possibly uncountable, and each is a measurable space. Consider the -algebra for some subset , which is often taken to be countable. This -algebra is naturally associated with the product topology restricted to S, which is strictly weaker than the product topology on the full index set T.

Theorem 2. Let S be a finite set, endowed with the discrete σ-algebra . Consider the infinite product spaceand let denote the coordinate projections, i.e., . Define, for each ,so that is the product σ-algebra on . Then, for every ,That is, the σ-algebra generated by finitely many coordinate random variables is strictly contained in the σ-algebra generated by the entire infinite process. Proof. By definition,

consists of all events that depend only on the first

n coordinates of

. That is,

if and only if there exists a subset

such that

Therefore, each

is finite, since

implies

.

To show that the inclusion is strict, consider the event

where

is fixed.

We can express

A as

Each set

belongs to

, and hence,

by closure of

-algebras.

However, for any finite n, since membership in A depends on infinitely many coordinates: for any two sequences that coincide on the first n coordinates but differ afterwards, one may have infinitely many occurrences of , while the other may not. Thus, A cannot be measurable with respect to .

Consequently,

so,

. □

Under these conditions, it may happen that the conditional probability , for some , fails to be -measurable. The issue stems from the fact that the regular conditional probability, typically constructed as a -measurable function, may not be measurable with respect to the weaker topology-induced -algebra . As a result, conditional expectations or conditional distributions may not exist in the usual sense or may not be representable by a measurable function. So, the subjective definition of coherent conditional probability can be considered, which does not require that the conditional probability is measurable with respect to the -field of the conditioning events.

4. The Proposed Model

A new model of coherent upper previsions defined by the Choquet integral with respect to Hausdorff outer measures has been introduced.

Choquet Integral

We recall the definition of the Choquet integral [

29,

30] with the aim to define upper conditional previsions by the Choquet integral with respect to the dimensional Hausdorff outer measures and to prove their properties. The Choquet integral is an integral with respect to a monotone set function. Given a non-empty set

and, denoted by

, the family of all subsets of

a monotone set function, also called capacity,

is such that

(⊘)=0, and if

A,

B∈

with

A⊂

B, then

(

A) ≤

(

B).

Let be a field of subsets of , i.e., a collection of sets closed under finite unions, finite intersections, and relative complements.

A set function is called a measure on the field if it satisfies the following properties:

.

Countable additivity:

For any disjoint sets

, and

, we have

is a probability measure on

if

is a measure such that

Given a monotone set function

on

, the

outer set function of

is the set function

defined on the whole power set

by

On a field

S, the outer set function

of

is sub-additive if

is ([

30] (Proposition 2.4)). So, the outer set function of a measure defined on a field

S is sub-additive.

The inner set function of

is the set function

defined on the whole power set

by

Let

be a monotone set function defined on

, and let

be an arbitrary function on

. Then, the set function

is decreasing, and it is called a

decreasing distribution function of

X with respect to

. If

is continuous from below, then

is right continuous.

A function

X:

is called upper

-measurable if

Given an upper

-measurable random variable

X:

with decreasing distribution function

, the Choquet integral of

X with respect to

is defined if

through

The integral is in ℜ or can assume the values , ∞, and ‘non-existing’.

For upper

-measurable random variable

X, we have

If

X ≥ 0 or

X ≤ 0, the integral always exists. In particular, for

X ≥ 0, we obtain

If

X is bounded and

= 1, we have that

If is a -additive measure, the Choquet integral coincides with the Lebesgue integral except for infinite measures.

In the following example, it is shown that if conditional probability is required to be -measurable, and is properly contained in the -field of the underlying probability space, then it contradicts a necessary condition for coherence.

Example 6. Consider the product space endowed with the product σ-algebra and the product measure . Each coordinate projection is independent and identically distributed.

Let be the σ-algebra generated by the values of the process on the rational points. Note that is strictly smaller than and corresponds to the information given by a countable dense subset of coordinates.

Note that , since the information in (i.e., the values of ω on a countable dense set) is insufficient to determine whether a path ω is continuous on the entire interval. Continuity is a topological property that depends on the behavior of the function at all points, not just a countable subset.

Now, if we define the conditional probability in the axiomatic way, requiring it is -measurable, we havesince , and so, the conditional probability is not coherent in the sense of de Finetti and Walley, because it does not satisfy a necessary condition for coherence [25] (Section 6.2.6). 5. Bayesian Conditional Models Based on Hausdorff Outer Measures

In finite-dimensional normed spaces, it is possible to adopt a unified Bayesian model of coherent conditional probability based on outer Hausdorff measures defined on the metric spaces endowed with the metrics induced by the norms. Since the Hausdorff dimension is invariant under bi-Lipschitz mappings, and all norms on a finite-dimensional vector space are bi-Lipschitz equivalent, the corresponding Hausdorff outer measures are mutually absolutely continuous. As a result, they share the same null sets, allowing for a consistent probabilistic framework across all such norm-induced metric structures.

In contrast, in infinite-dimensional normed spaces, not all norms are equivalent—hence, not all induced metrics are bi-Lipschitz equivalent. Consequently, the Hausdorff dimension of a set is not invariant, different Hausdorff outer measures may assign different null sets, and a unique Bayesian model based on a single Hausdorff outer measure cannot, in general, be consistently defined. In such settings, distinct conditional probability models based on different Hausdorff measures must be considered, as different normed structures may not agree on which sets have measure zero.

5.1. Hausdorff Outer Measures and Hausdorff Dimension

Let

be a metric space. For any

, we define the

s-dimensional Hausdorff outer measure on

as follows [

31]. For

, consider all countable covers

of a set

such that

for all

i. Define

The

s-dimensional Hausdorff outer measure is then given by the limit

The function defined above is an outer measure, i.e.,

,

whenever ,

for any sequence .

Moreover,

is a

metric outer measure, meaning that for any two sets

with

, we have

This property ensures that the Carathéodory construction of measurable sets relative to

coincides with the Borel

-algebra on

. Hence, the restriction of

to Borel sets defines a complete measure, also called the

s-dimensional Hausdorff measure.

The

Hausdorff dimension of a set

is defined in terms of the behavior of

as

s varies:

Intuitively,

measures the “size” of

A at different scales

s, and the Hausdorff dimension captures the critical threshold at which the measure transitions from infinite to zero. This concept generalizes the notion of integer dimensions and provides a fundamental tool for quantifying the geometric complexity of fractal sets.

Theorem 3. Let be a metric space, let be a partition of Ω and the Borel σ-field induced by the metric d. For each , denote by the Hausdorff dimension of B in the metric space and denote by a 0–1 valued finitely additive, but not countably probability defined on B. Then, the set function defined on byis a coherent upper conditional probability. Proof. For each

, the coherence of the upper conditional probability has been proven in Theorem 3 of [

15]. □

Remark 1. If, fixed , the metric d is allowed to vary, then every set is associated with a credal set of coherent upper conditional probabilities defined byIn particular, in infinite-dimensional normed spaces, not all norms are equivalent—hence, not all induced metrics are bi-Lipschitz equivalent. Consequently, the Hausdorff dimension of a set is not invariant, and different dimensional Hausdorff outer measures can be defined for the same set B in different metric spaces. The class contains all the conditional probabilities defined by different dimensional Hausdorff measures associated with the same conditioning event B but in different metric spaces, which do not share the same null sets. In finite-dimensional normed spaces, the class contains Hausdorff measures of the same dimension (since all the induced metrics are bi-Lipschitz) that share the same null sets. If

is of bounded variation, by the previous model we can obtain a model of coherent countably additive probability on the Borel

-field of the metric space by using the countably additive Mobius transform ([

32,

33,

34,

35]).

5.2. Countably Additive Möbius Transform

Let be an algebra of subsets of , properly contained in , and let be a monotone set function. Let denote the class of all normalized monotone set functions with values in .

Consider the two subsets of

:

where, for a fixed

, the function

is defined on

by

It is continuous from above, whereas a general -valued supermodular set function need not be continuous. The function is supermodular and is a belief function since it is totally monotone.

When

is finite, every filter has the form

for some nonempty set

K, and in this case

is a coherent lower probability (Section 2.9.8 of [

25]). In game theory,

is called a

unanimity game.

Definition 8. Let be a coalition. The unanimity game on K is the game where In other words, a coalition

S has worth 1 (is winning) if it contains all players of

K and 0 (is losing) otherwise.

and the equality

holds when

is finite.

Let us consider the

tilde operator defined for any

-measurable random variable

X and any

-valued monotone set function

:

If

X is the indicator of an event

, then

Although

is a field, the set system

is not a field in

, except in the trivial case

. Hence, we consider the field

generated by

, i.e., the smallest field containing it.

If

is a measurable space and

, then

is a

-field on

E, called the

trace σ-field.

Let and denote the trace -fields generated by in and , respectively.

Definition 9. A monotone set function is said to be of bounded variation if there exist monotone set functions such that . Let denote the class of set functions on of bounded variation for which and are totally monotone.

Definition 10. Given a monotone set function ν on , the additive Möbius transform is uniquely determined on by Moreover, as shown in [

34], integrals are preserved under the Möbius transform:

Example 7. For a fixed nonempty set , the Choquet integral with respect to on isThe same expression holds for the restriction of to a field and an -measurable X, even when . The Möbius transform of is given by A set function

on an algebra

is totally monotone if and only if its Möbius transform

is monotone (i.e., nonnegative) ([

36,

37]).

In Theorem 6.2 of [

34], the following result is proved.

Theorem 4. If , the Möbius transform can be uniquely extended to . It is σ-additive and is called the σ-additive Möbius transform of ν. It is a signed (possibly negative) additive set function.

The theorem holds, because if

with

, then there exists

such that

for all

(Lemma 6.1 of [

34]). Thus, any monotone set function on

is trivially continuous from above at Ø; so, any additive set function is automatically

-additive. Lemma 6.1 of [

34] is proved by contradiction: assuming

for all

n, one constructs a sequence

with each

such that there exists

satisfying

, contradicting

.

Example 8. Let be an uncountable set and fixed define the countable additive probability on the Borel σ-field byThen, , and sincethen the Möbius transform is In the following theorems, the countably additive Möbius transform is considered to define coherent countably additive conditional probabilities and coherent conditional previsions.

Theorem 5. Let be a metric space, let be a partition of , and let be the Borel σ-field induced by the metric d. For each , denote by the Hausdorff dimension of B in the metric space, and denote by the countably additive Möbius transform. Then, the set function defined on byis a coherent countably additive conditional probability. Proof. For each

, the coherence of the conditional probability has been proven in Theorem 4 of [

35]. □

Theorem 6. Let be a metric space, and let be the Borel σ-field. Let be a partition of Ω. For every , denote by s the Hausdorff dimension of the conditioning event B and by the Hausdorff s-dimensional outer measure. Let be the σ-additive Möbius transform of a finitely additive conditional probability ν of bounded variation. Then, for each with a positive and finite Hausdorff s-dimensional outer measure, the functional is defined on the class of all -measurable random variables bywhich is a continuous linear conditional prevision. For each

, the coherence of the upper conditional prevision has been proven in Theorem 5 of [

35].

6. Examples

In this section, some examples of stochastic processes in infinite-dimensional normed spaces are considered.

Example 9. Consider the separable Hilbert space with the standard inner product. Let μ be a probability measure on , for instance a Gaussian measure , where I is the identity operator.

Classically, conditioning on a finite-dimensional subspace, such as fixing the first coordinate , gives the conditional probabilityHowever, in infinite-dimensional spaces, , making the classical definition ill-defined. Instead of a zero-probability event, we define a conditional probability applying Theorem 4The conditioning event has a Hausdorff measure equal to infinite in its Hausdorff dimension equal to 1 (); then, by Theorem 4, the conditional probability can be defined by the countably additive Möbius transform of a finite additive probability of bounded variation. This provides a non-degenerate and coherent definition of conditional probability.

Example 10. Consider truncate to with . Classically, is undefined, because .

Using the 1-dimensional Hausdorff measure ((that is the 1-dimensional Lebesgue) along the line , the conditional probability isThis coincides with the classical conditional Gaussian density, but it is derived via the Hausdorff measure approach rather than dividing by a probability-zero event. In general, in , conditioning on or any finite set of coordinates results in a zero-probability event in the classical sense. Using Hausdorff measures, we can define the hyperplane and use the Hausdorff measure on this hyperplane (if it is positive and finite) to define the conditional probability. Thus, the Hausdorff measure-based conditional probability respects the geometry of infinite-dimensional spaces and resolves inconsistencies that arise with classical definitions based on Radon–Nikodym derivatives.

Example 11. Let be a probability space and a filtration, that is, an increasing family of sub-σ-algebras of .

A stochastic process adapted to the filtration is called a martingale if, for every ,

,

,

for all , -almost surely.

This formulation captures the intuitive idea that the process has “fair” increments: its future value has no predictable drift given the present information encoded in .

Let be a separable metric space, and let denote the s-dimensional Hausdorff measure on Ω for some . If is positive and finite, we consider a random variable taking values on , where is the Borel σ-field.

Given an integrable function and a sub-σ-algebra , the coherent conditional expectation of X with respect to and the Hausdorff measure is the function (up to -a.e. equality) if , satisfying In the following example, it has shown that a set can have different Hausdorff dimensions and Hausdorff measures in different etric spaces, and so, according to the model proposed in this paper, different conditional previsions can be obtained in different metric spaces with metrics that are not bi-Lipschitz.

Example 12. Letand define a non–bi-Lipschitz metric Consider the 1-parameter family of functionsThe map is injective; so, we identify B with but endowed with different metrics inherited from V. 6.1. Hausdorff Dimension Under and

For ,Thus, is isometric to the ordinary interval , and therefore, Under the snowflake metric ,and for snowflake metrics , the Hausdorff dimension is (see Appendix A). Hence, 6.2. Hausdorff Measures on B

For , the 1-dimensional Hausdorff measure is the Lebesgue measure: For , the 2-dimensional Hausdorff measure satisfies(because a length becomes diameter , squared); hence,where C normalizes the total measure on to a finite nonzero value. After normalizing on B, Let the gamble beOn B, this is simply . This is strictly larger than the value because the weight near (i.e., ) increases the mass on the functions with the smallest c, which maximizes .while Although the underlying set B is the same subset of V, the change from to the non-bi-Lipschitz metric changes both the Hausdorff dimension () and the associated Hausdorff measure; after normalization, this leads to a different conditional upper prevision: 7. Discussion

In this section, we compare the results proposed in this paper with the Extreme Value Theory, one of the theories proposed in literature to manage rare events.

7.1. Extreme Value Theory

Extreme Value Theory (EVT) studies the probabilistic behavior of the extreme observations in a sequence of random variables, such as the maximum or minimum values observed in a large sample. While classical limit theorems (such as the Law of Large Numbers or the Central Limit Theorem) describe the behavior of averages or sums, EVT focuses on the tail behavior of distributions and the occurrence of rare extreme events.

Typical examples include the highest annual flood level of a river, the maximum daily wind speed, or the largest financial loss in a given period.

Let

be a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables with common distribution function

. Define the sample maximum as

The goal of EVT is to determine the possible non-degenerate limit distributions of the normalized maxima

as

.

7.2. Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko Theorem

Theorem 7 (Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko).

Suppose that there exist sequences of constants and such thatfor some non-degenerate distribution function G. Then, G must belong to one of the following three families of extreme value distributions: Gumbel type (light tails): Fréchet type (heavy tails): Weibull type (bounded upper support):

7.3. Unified Representation: The Generalized Extreme Value Distribution

The three possible limit laws can be expressed in a unified form known as the

Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution:

where

is the location parameter,

is the scale parameter, and

is the shape parameter. The three types correspond to

EVT characterizes the limiting behavior of sample extremes and shows that, after appropriate normalization, the distribution of maxima converges to one of three universal forms (Gumbel, Fréchet, Weibull), unified in the Generalized Extreme Value family. This result provides a rigorous statistical foundation for modeling and predicting rare high-impact events.

7.4. Comparison Between Extreme Value Theory and the Bayesian Model Based on Hausdorff Measures

The Extreme Value Theory (EVT) and the Bayesian probabilistic model based on Hausdorff measures represent two fundamentally different approaches to the analysis of rare events.

In the classical framework of EVT, one begins by considering a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables

with the primary goal of determining the limiting distribution of the maximum value

as the sample size

n tends to infinity. The theory focuses on characterizing the asymptotic behavior of the extremes and identifying the universal limit laws (Gumbel, Fréchet, or Weibull) that govern such behavior under appropriate normalization.

In contrast, the proposed Bayesian model based on Hausdorff measures does not assume any specific probability distribution for the random variables, nor does it require them to be independent. In this framework, the conditioning information is represented by a subset of a metric space, characterized by its Hausdorff dimension . This value acts as an aggregation operator, encoding the amount of information carried by the conditioning event.

It determines the corresponding Hausdorff dimensional measure , which is then used to define conditional probability.

Within this measure-theoretic Bayesian framework, rare events are identified as those to which the Hausdorff measure assigns zero probability. Hence, while EVT derives rarity from the asymptotic behavior of maxima under the assumption of independence and identical distributions, the Hausdorff-based Bayesian model defines rarity through geometric and dimensional properties of the underlying information set, without assuming a particular probabilistic structure.

8. Conclusions

In this work, we have introduced a Bayesian updating model defined through Hausdorff measures, offering a geometric perspective on probabilistic inference. The proposed framework reveals that the notion of a rare event, understood as an event with zero probability, is not an intrinsic property of the probabilistic structure alone but rather depends on the underlying metric space in which the measure is defined. In particular, the metric itself plays a crucial role in determining which subsets of the space are assigned vanishing probability.

This observation highlights the interplay between geometry and probability: by altering the metric structure, one may effectively reshape the probabilistic characterization of events, thereby influencing the interpretation of uncertainty and the behavior of Bayesian updates. Consequently, the model provides a flexible tool for studying stochastic systems where the notion of distance and, hence, of similarity among outcomes are subject to modeling choices. Future research may further explore how different metric configurations affect convergence properties, posterior stability, and the emergence of rare events in high-dimensional or non-Euclidean settings. Such notions arise naturally in the study of stochastic processes defined on fractals.

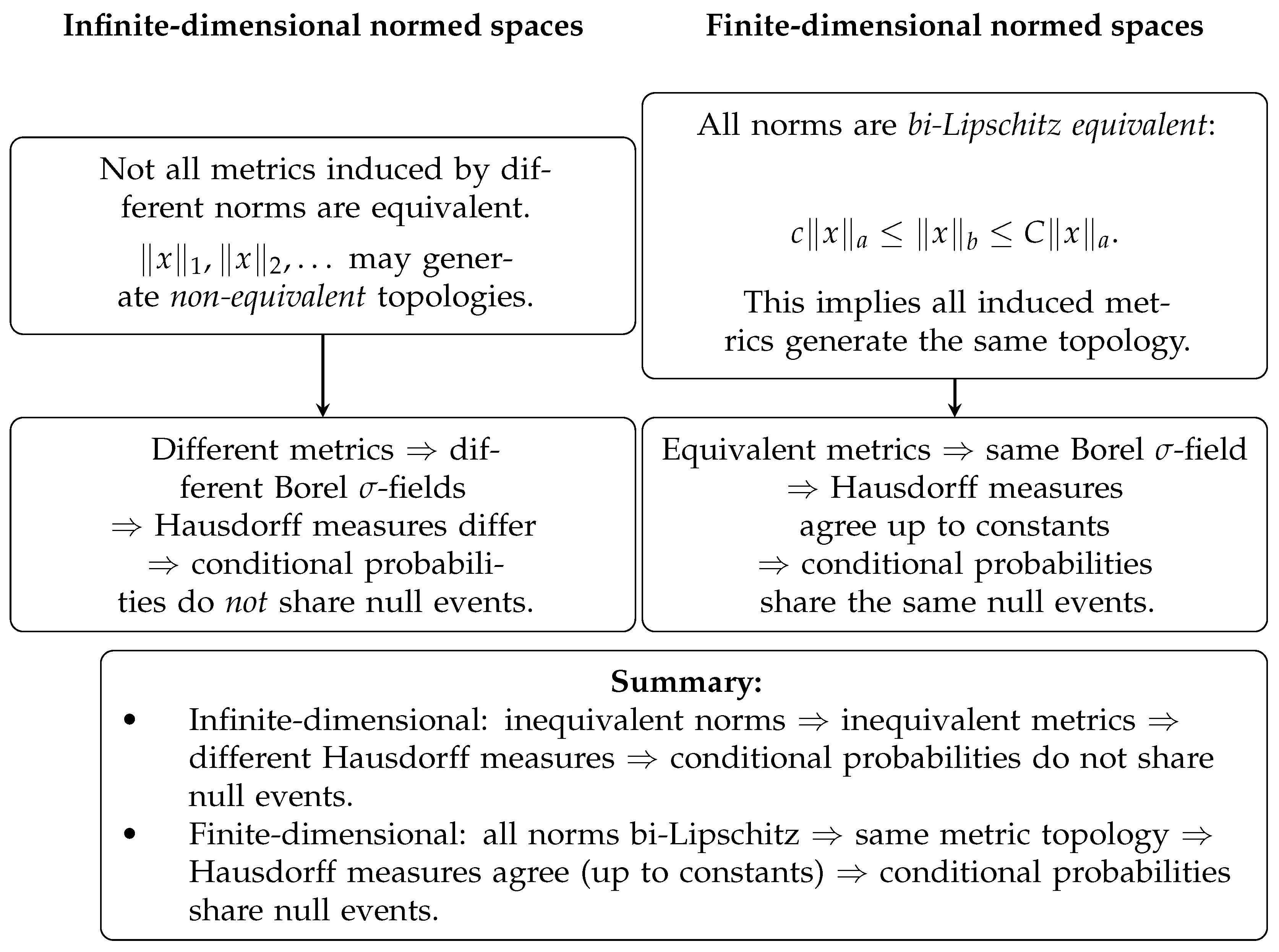

Figure 1 shows why a single Hausdorff model of conditional probability suffices in finite dimensional normed spaces, while a family of Hausdorff models is needed in infinite-dimensional normed spaces to assess conditional probabilities.