A Study of Improved Inversion Algorithms for Surface–Borehole Transient Electromagnetic Data Based on BFGS Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principal Theories of Surface–Borehole TEM

2.1. Basic Equations

2.2. Algorithm Verification

3. Inversion of Surface–Borehole TEM

3.1. Construction of Objective Function

3.2. Optimization Using BFGS Methods

4. Inversion Example

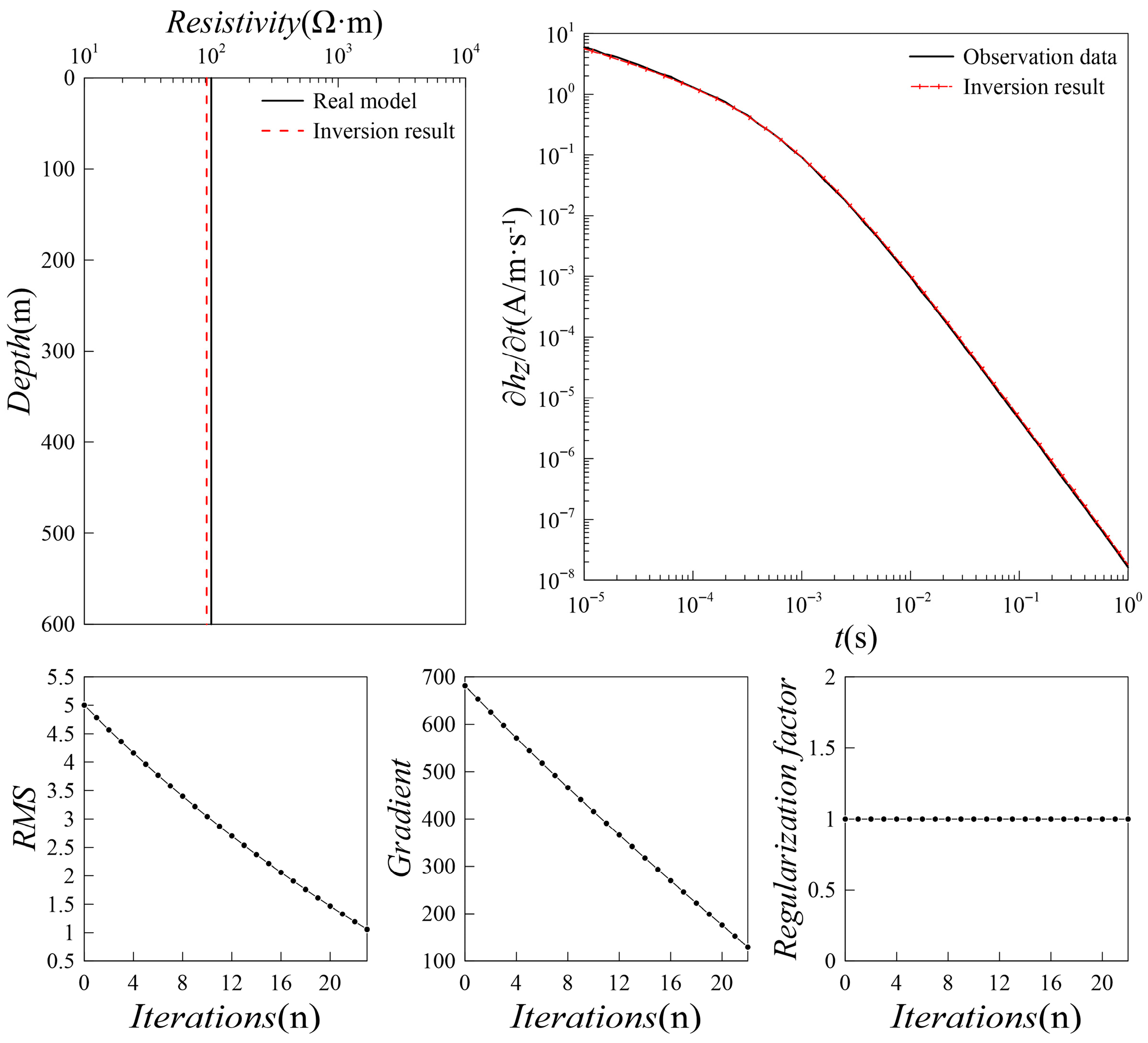

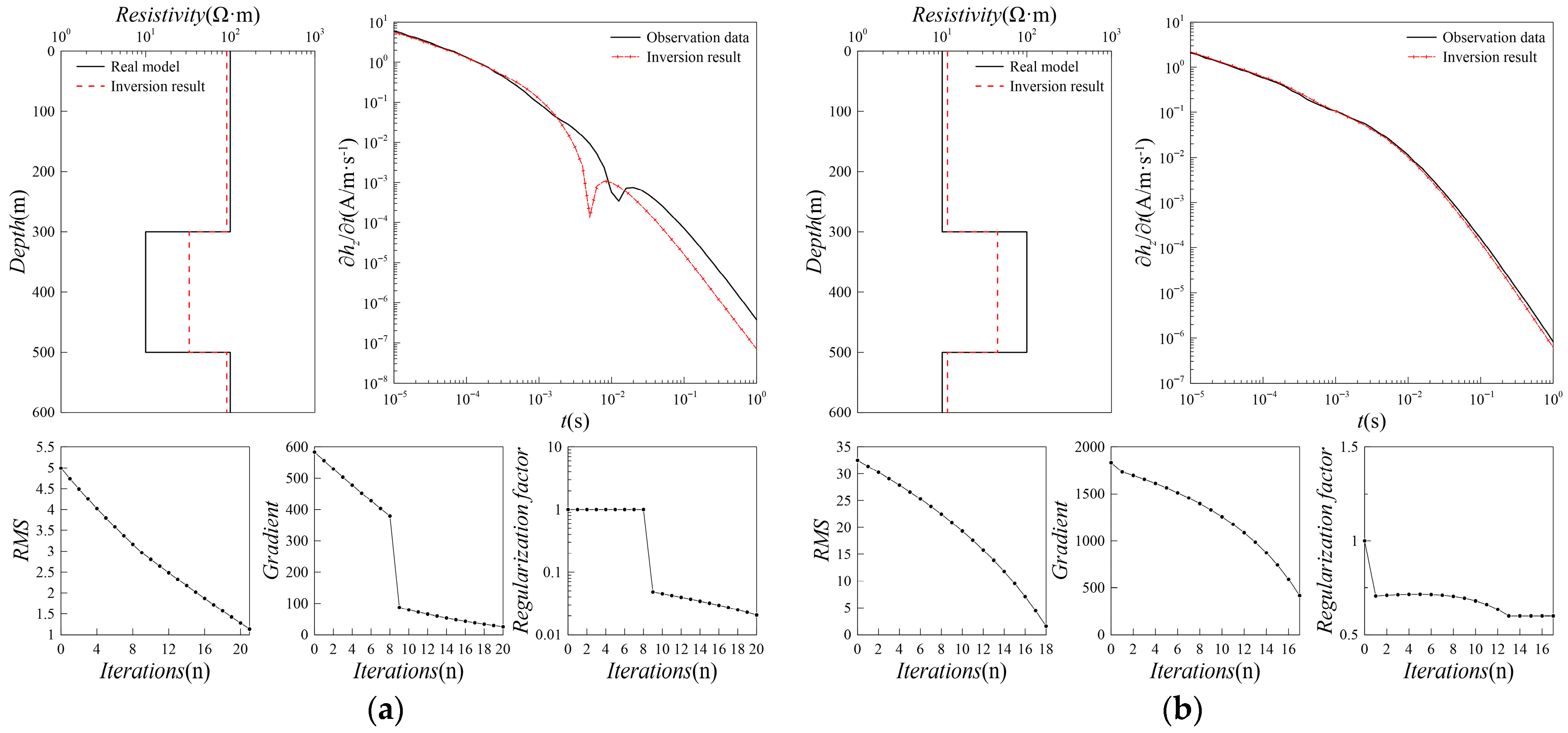

4.1. Layered Geoelectric Model

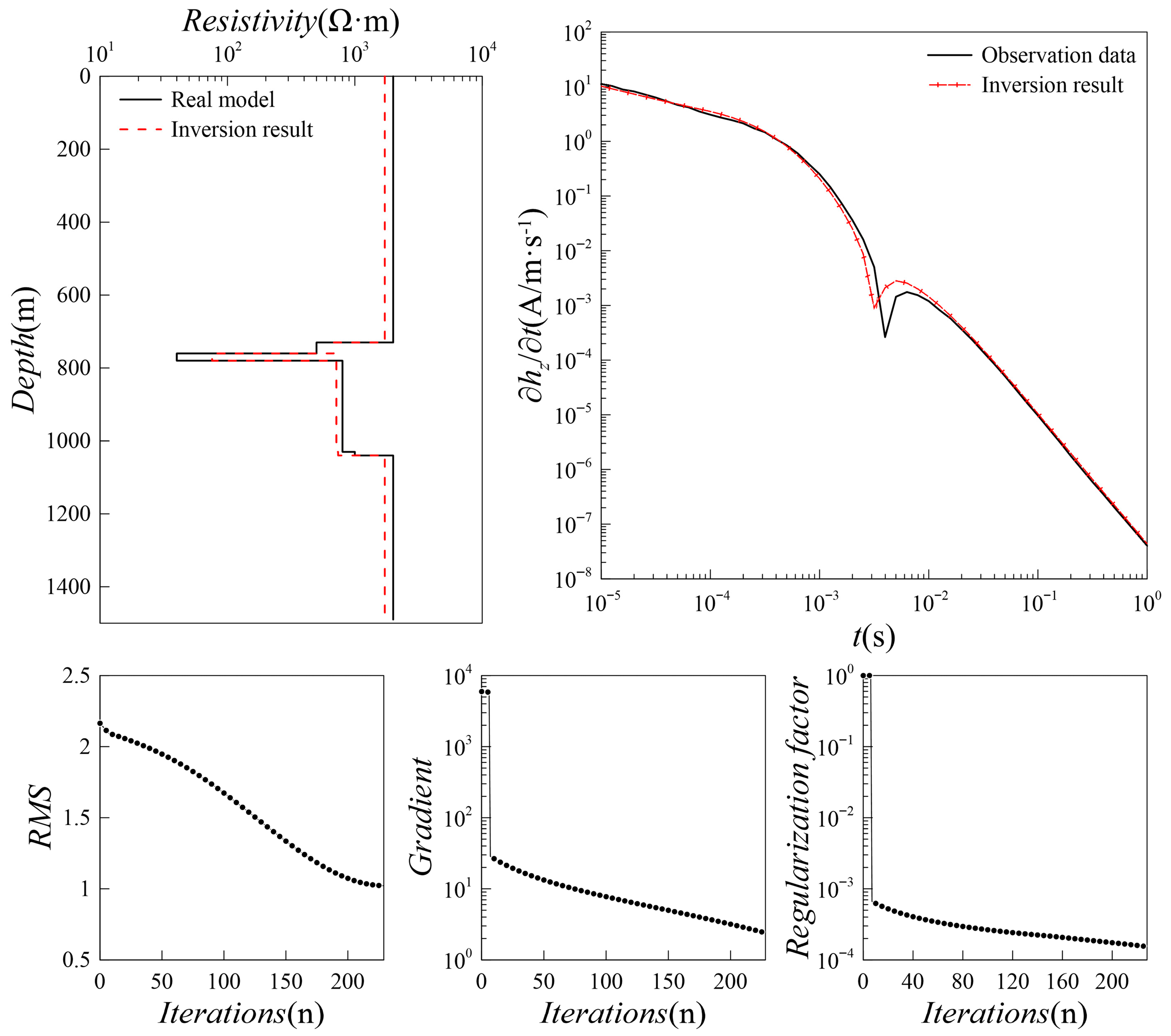

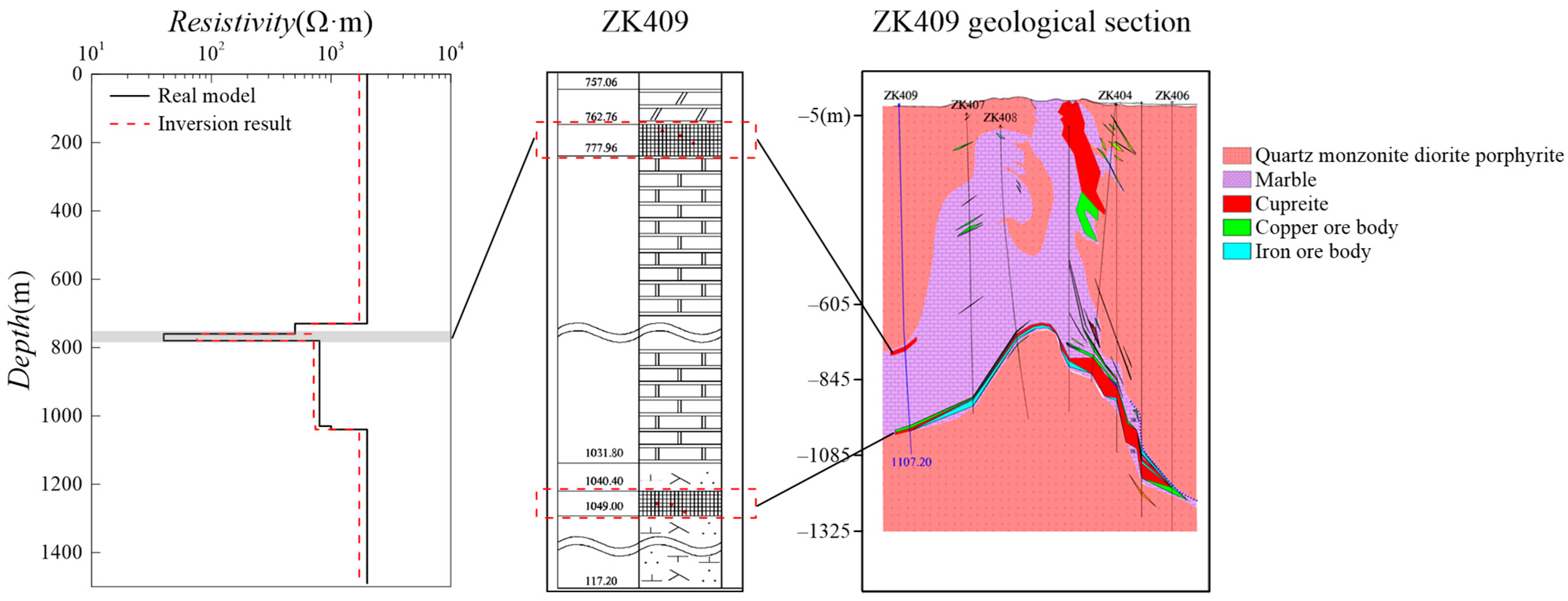

4.2. Complex Geoelectric Model

5. Discussion

6. Results

- The proposed algorithm effectively recovers the original formation model. Even in the presence of noise or irregularities in the observed data, the BFGS method yields stable and reliable solutions. Furthermore, selecting an appropriate number of model layers significantly reduces inversion time and improves computational efficiency.

- During the iterative process, the choice of a suitable regularization factor and the balance between data and model weights help prevent overfitting and reduce the required number of iterations. In addition, step size optimization further enhances computational performance.

- In formations with complex electrical structures, incorporating high-quality prior information from borehole data substantially mitigates the risk of non-unique solutions and improves inversion stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaufman, A.A.; Keller, G.V. Frequency and Time Domain Electromagnetic Sounding; Wang, J.M., Translator; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.S. Deep transient electromagnetic sounding. Seismol. Geol. 1989, 11, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Eadie, T.; Staltari, G. Introduction of down hole electromagnetic methods. Explor. Geophys. 1987, 18, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Fullagar, P.K. Inversion of down hole TEM data using circular current filaments. Explor. Geophys. 1987, 18, 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Mogi, T.; Kusunoki, K.; Kaieda, H.; Ito, H.; Jomori, A.; Jomori, N.; Yuuki, Y. Grounded electrical-source airborne transient electromagnetic survey of Aso Volcano, Japan. Explor. Geophys. 2014, 45, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q.F.; Feng, X.L.; Huang, Y. Research on key technical problems of surface-borehole TEM. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2019, 43, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, A.C. Interpretation of down-hole transient EM data using current filaments. Explor. Geophys. 1987, 18, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Mao, Y.; Yan, L.; Chen, W.H.; Yang, J.P.; Xie, X.B.; Zhou, L.; Li, H.J. Key Technologies for Surface-Borehole Transient Electromagnetic Systems and Applications. Minerals 2014, 14, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, J.; Massie, D. Noise reduction of don-hole three-component TEM probes. ASEG Ext. Abstr. 2001, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.C. Response Characteristics Analysis and Occam Inversion of Ground-Well Transient Electromagnetic Method. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Shiyou University, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Deng, X.H.; Guo, X.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.J.; Wang, X.C. Typical cases of applying borehole TEM to deep prospecting in crisis mines. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 37, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.F.; Zhan, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.C.; Liu, Y.C.; Zhao, H.L. Present study situation review of borehole transient electromagnetic method. Coal Geol. Explor. 2022, 50, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, A.; Strack, K.; Hanstein, T. Surface-to-borehole TEM for reservoir monitoring. SEG Tech. Program Expand. Abstr. 2011, 30, 1882–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.X.; Pan, H.P. Numerical simulation analysis of surface-hole TEM responses. Chin. J. Geophys. 2012, 55, 1046–1053. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.X.; Hu, X.Y.; Pan, H.P.; Zhou, F. Numerical analysis of multicomponent response of surface-hole transient electromagnetic methods. Appl. Geophys. 2017, 14, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikov, N.O.; Antonov, E.Y.; Yaroslav, K.L.; Vladimir, Q.; Plotnikov, A.E.; Stefanenko, S.M.; Alexandr, S. Effects of borehole casing on TEM response. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2014, 55, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Li, X.; Zhi, Q.Q.; Qi, Z.P.; Guo, J.L.; Deng, X.H. Analysis of three component TEM response characteristic of electric source dill hole TEM. Prog. Geophys. 2017, 32, 1273–1278. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Despina, K.; Maria, K.; Filippos, V.; Pantelis, S.; Stephen, K.; Nikos, L.S. A Transient Electromagnetic (TEM) Method Survey in North-Central Coast of Crete, Greece: Evidence of Seawater Intrusion. Geosciences 2018, 8, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, Z.; Liu, B.X.; Wu, Y.Q.; Yi, H.C. Numerical simulation and anomalies qualification based on ground-well transient electromagnetic methods. Eur. J. Electr. Eng. 2019, 21, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Han, S.X.; Xue, G.Q. Analysis on the full-component response and detectability of electric source surface-to-borehole TEM method. Chin. J. Geophys. 2019, 62, 1969–1980. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.Y.; Han, S.; Khan, M.Y.; Chen, W.; Yiming, H.; Zhang, L.; Hou, D.Y.; Xue, G.Q. A Surface-to-Borehole TEM System Based on Grounded-wire Sources: Synthetic Modeling and Data Inversion. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2020, 177, 4207–4216. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.L.; Jiang, T.; Guo, H.; Ning, H.; Liu, H. Characteristics of axial anisotropic borehole transient electromagnetic three-component response. J. Earth Environ. 2020, 42, 737–748. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, Y.; Walter, J.; Chesnaux, R. Transient Electromagnetic (TEM) Surveys as a First Approach for Characterizing a Regional Aquifer: The Case of the Saint-Narcisse Moraine, Quebec, Canada. Geosciences 2021, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Mao, Y.R.; Wang, X.Y.; Yan, L.J.; Zhou, L. Surface-borehole transient electromagnetic responses in 3D anisotropic media. Oil Geophys. Prospect. 2024, 59, 1184–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yin, C. Ground-Well Transient Electromagnetic Inversion Method Based on Non-Structural Finite Element Method. Invention Patent China CN202110257661.22021-06-11, 11 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, S.X.; Shan, H.M.; Peng, Q.H. Numerical simulation of water-bearing coal goaf using ground-borehole TEM—A case study of Tongxin Coal Mine, Shanxi province, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1289469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y. Review on the study of grounded-source transient electromagnetic method. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2021, 45, 809–823. [Google Scholar]

- Nabighian, M.N. Electromagnetic Methods for Exploration Geophysics; Zhao, J.X.; Wang, Y.J., Translators; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Key, K. 1D inversion of multicomponent, multifrequency marine CSEM data: Methodology and synthetic studies for resolving thin resistive layers. Geophysics 2009, 74, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guptasarma, D.; Singh, B. New digital linear filters for Hankel J0 and J1 transforms. Geophys. Prospect. 1992, 45, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J. Digital filter algorithm of the sine and cosine transform. Chin. J. Eng. Geophys. 2004, 1, 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y. Long Wire Source Transient Electromagnetic Constrained Inversion. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.J.; Li, X.; Zhi, Q.Q.; Qi, Z.P.; Guo, J.L.; Deng, X.H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.C.; Yang, Y. Full field apparent resistivity definition of borehole TEM with electric source. Chin. J. Geophys. 2017, 60, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.B. Efficient 3D Forward Modeling Method and L-BFGS Inversion for Transient Electromagnetic Based on Backward Euler and Direct-Splitting Scheme. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.H.; Yin, C.C.; Qiu, C.K.; Hui, Z.J.; Zhang, B.; Ren, X.Y.; Weng, A.H. 3-D inversion of transient EM data with topography using unstructured tetrahedral grids. Geophys. J. Int. 2019, 217, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y. Geophysical Inversion Theory; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Y.; Cai, H.Z.; Liu, L.C.; André, R.; Hu, X.Y. Three-Dimensional Inversion of Long-Offset Transient Electromagnetic Method over Topography. Minerals 2023, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | ρ1/Ω·m | H1/m | ρ2/Ω·m | H2/m | ρ3/Ω·m | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform | 100 | − | − | − | − | Uniform |

| H | 100 | 300 | 10 | 200 | 100 | H |

| K | 10 | 300 | 100 | 200 | 10 | K |

| A | 1 | 300 | 10 | 200 | 100 | A |

| Q | 100 | 300 | 10 | 200 | 1 | Q |

| Type | RMS | g(m) |

|---|---|---|

| H | 1.13761 | 2.53553 × 101 |

| K | 1.58560 | 4.17237 × 102 |

| A | 1.02689 | 1.58472 × 104 |

| Q | 1.16834 | 2.66966 × 101 |

| Parameter | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-layer model | ρ/Ω·m | 20 | 500 | 50 | 1000 | |

| H/m | 150 | 250 | 200 | |||

| Five-layer model | ρ/Ω·m | 100 | 40 | 500 | 40 | 500 |

| H/m | 200 | 100 | 350 | 50 |

| Depth/m | Thickness/m | Lithology | Resistivity/Ω·m |

|---|---|---|---|

| 730 | 730 | Quartz monzodiorite porphyry | 2000 |

| 760 | 30 | Chalcolithic dolomitic marble | 500 |

| 780 | 20 | Copper–iron ore body | 40 |

| 1030 | 250 | Marble | 800 |

| 1040 | 10 | Quartz monzodiorite porphyry | 1000 |

| 1050 | 10 | Copper–iron ore body | 60 |

| Quartz monzodiorite porphyry | 2000 |

| Type | RMS | g(m) |

|---|---|---|

| Four-layer model | 1.02896 | 1.46892 × 102 |

| Five-layer model | 1.09228 | 1.33252 × 101 |

| Borehole model | 1.02215 | 2.39715 × 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Mao, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhou, L.; Xie, X. A Study of Improved Inversion Algorithms for Surface–Borehole Transient Electromagnetic Data Based on BFGS Method. Minerals 2025, 15, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121279

Li H, Mao Y, Yan L, Zhou L, Xie X. A Study of Improved Inversion Algorithms for Surface–Borehole Transient Electromagnetic Data Based on BFGS Method. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121279

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Haojin, Yurong Mao, Liangjun Yan, Lei Zhou, and Xingbing Xie. 2025. "A Study of Improved Inversion Algorithms for Surface–Borehole Transient Electromagnetic Data Based on BFGS Method" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121279

APA StyleLi, H., Mao, Y., Yan, L., Zhou, L., & Xie, X. (2025). A Study of Improved Inversion Algorithms for Surface–Borehole Transient Electromagnetic Data Based on BFGS Method. Minerals, 15(12), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121279