Study of Stibnite Dissolution in Nitric Acid in the Presence of Organic Acids

Abstract

1. Introduction

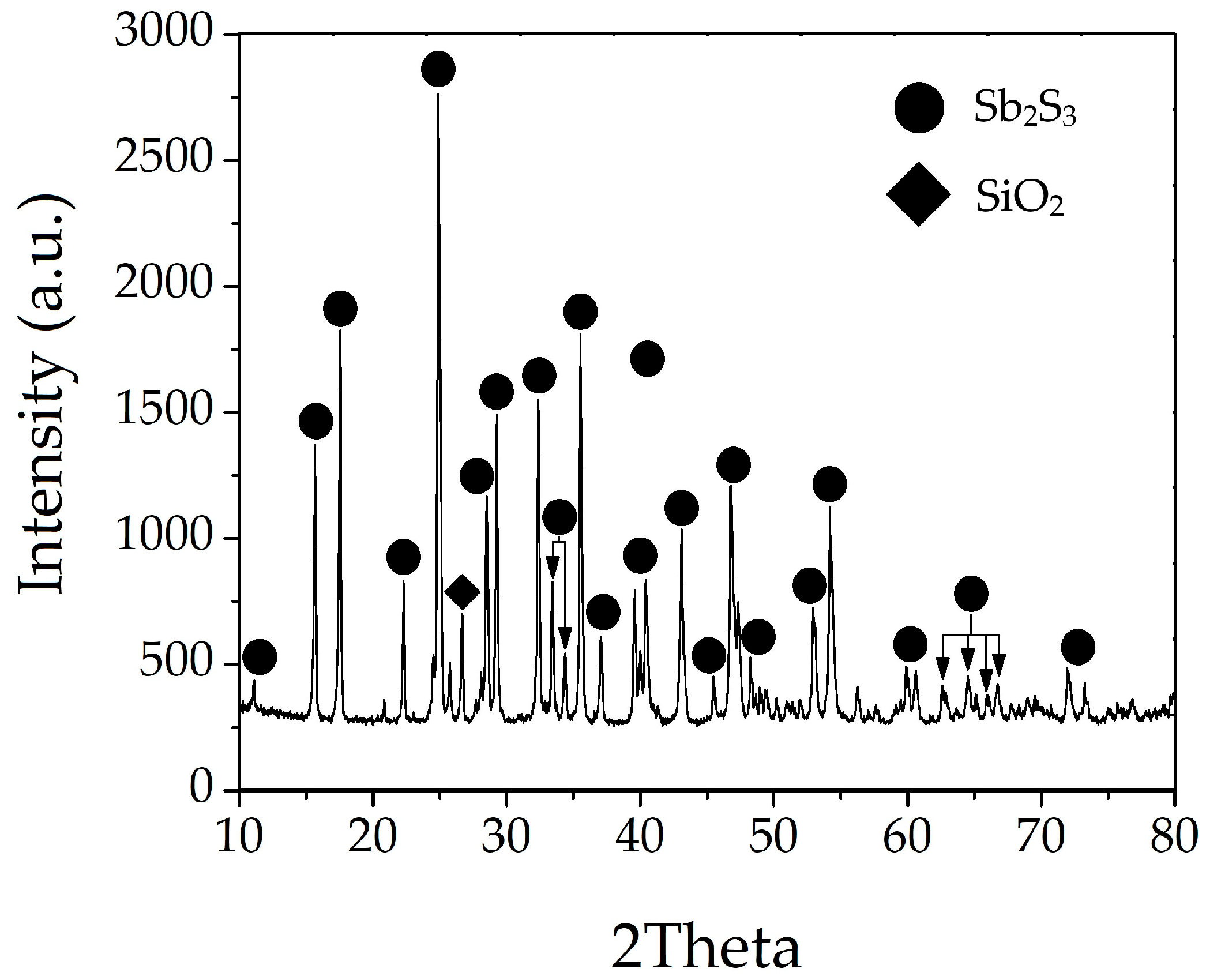

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis

2.2. Materials and Reagents

2.3. Experimental Procedure

3. Results

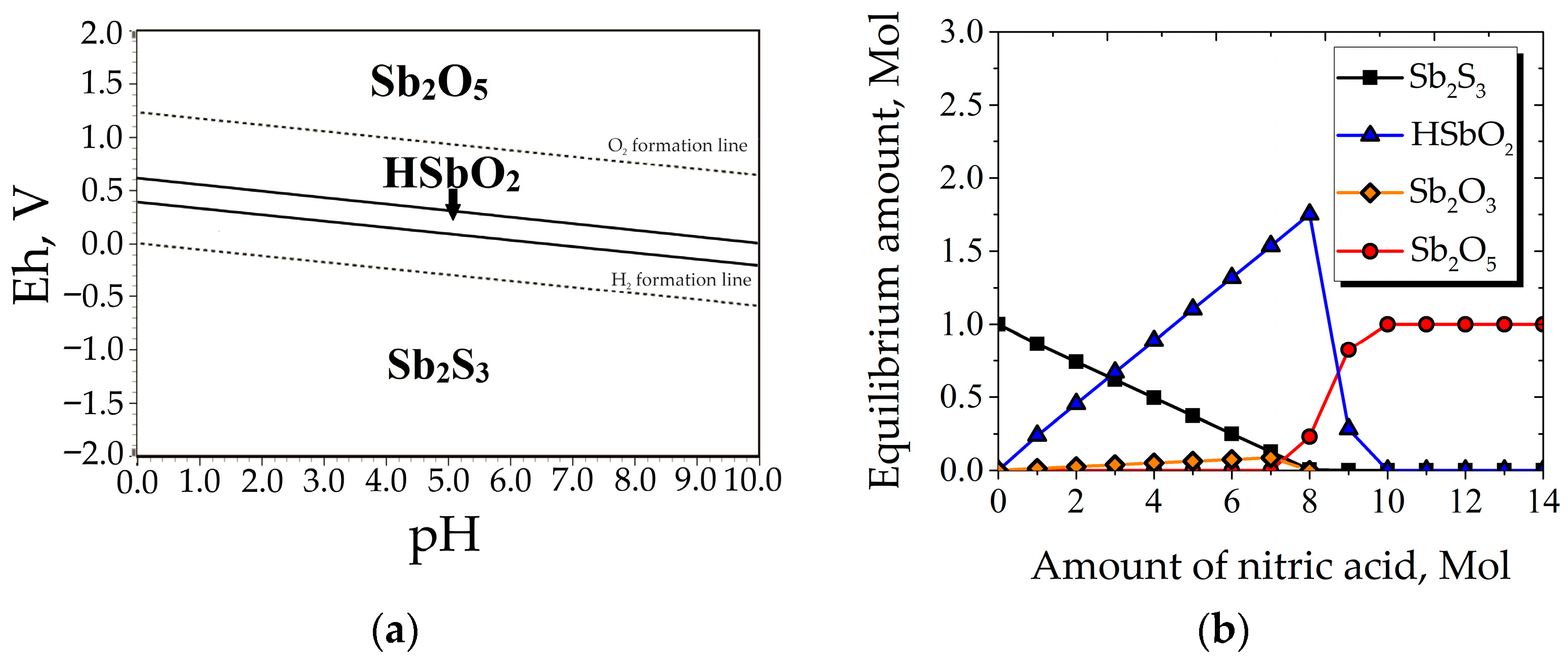

3.1. Thermodynamics of Nitric Acid Leaching of Stibnite

3.2. Nitric Acid Leaching of Stibnite with the Addition of Tartaric and Citric Acids

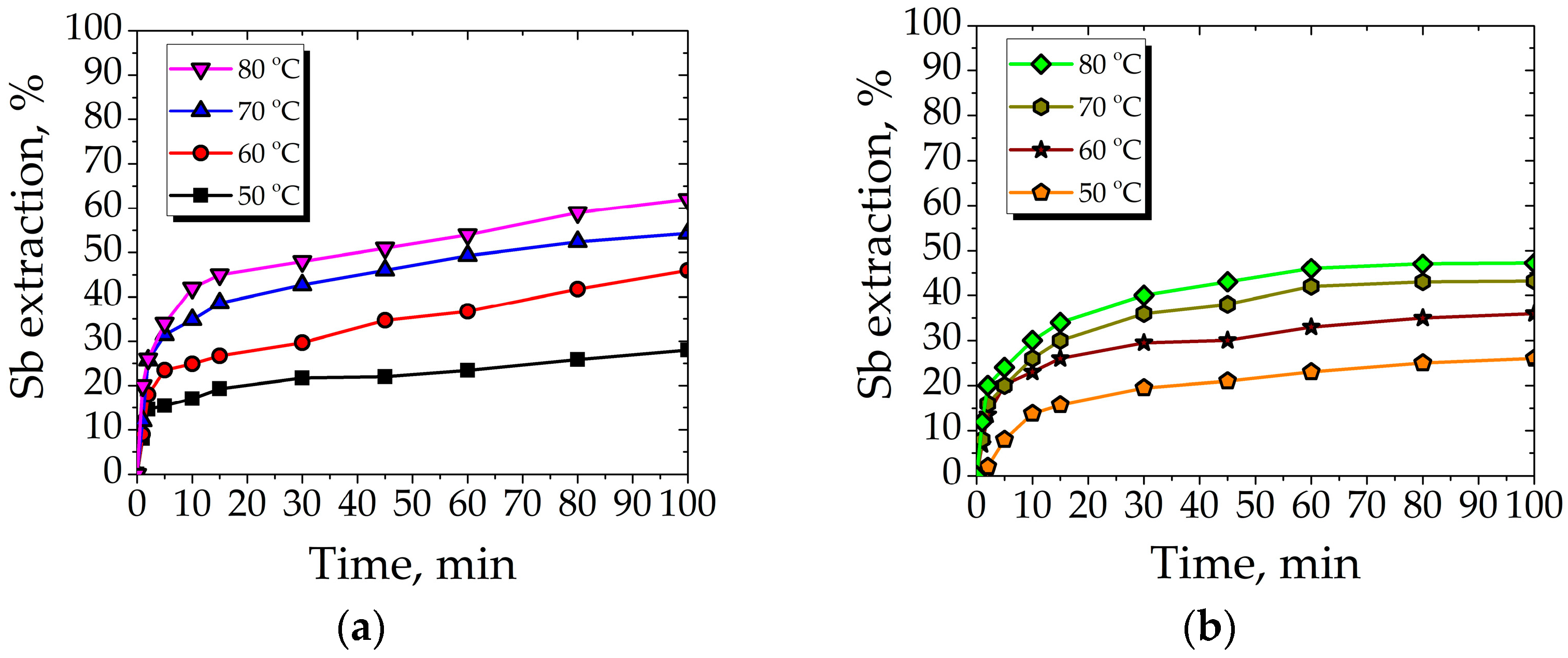

3.2.1. Effect of Temperature

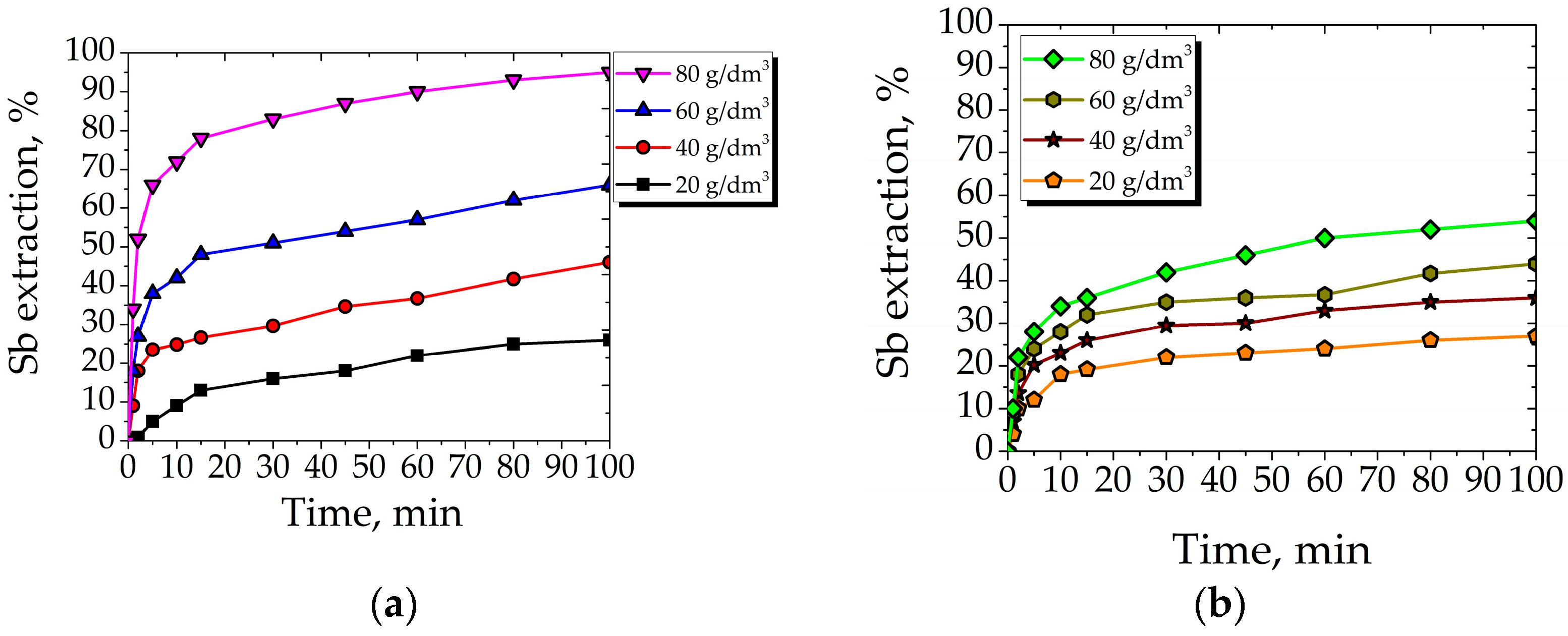

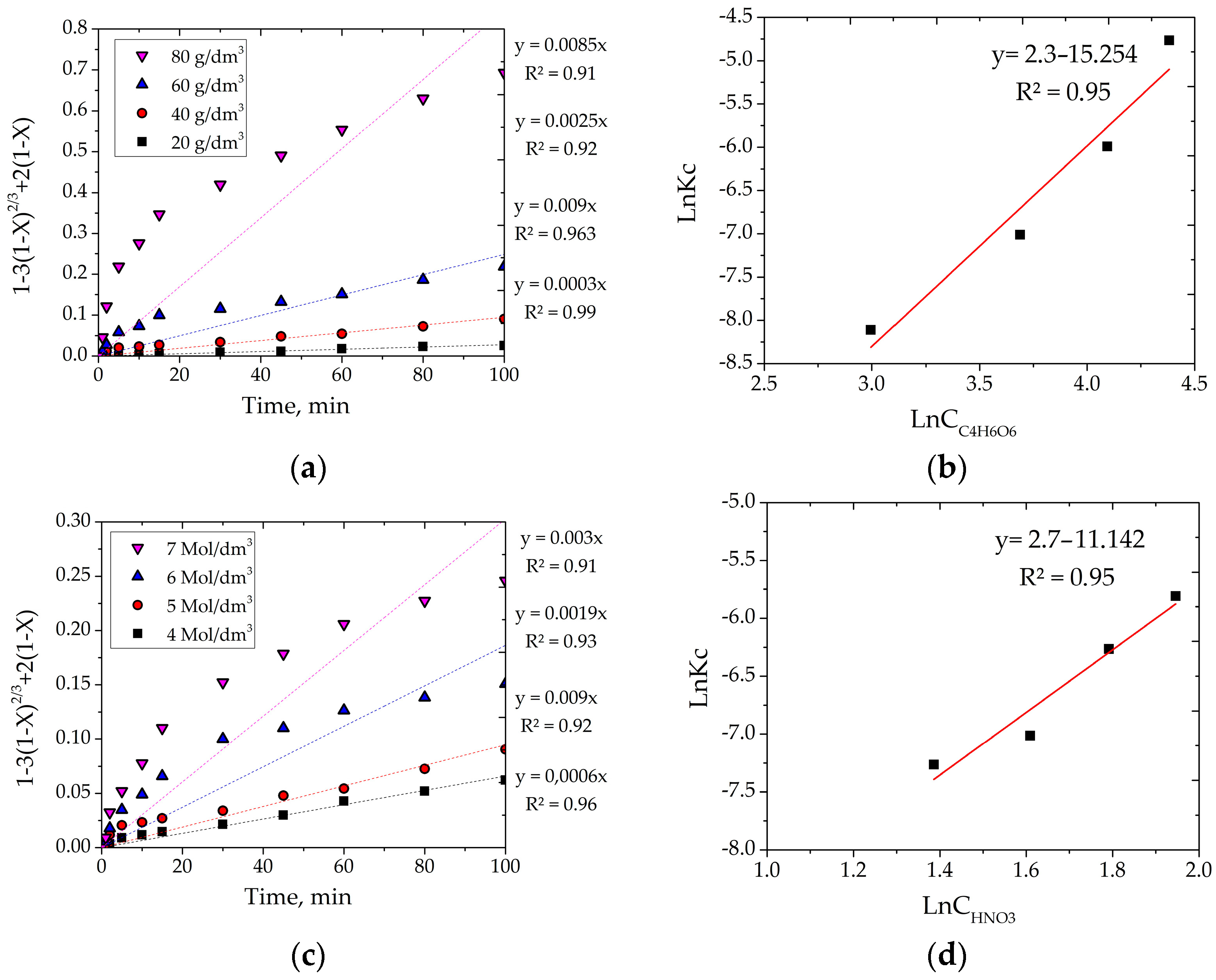

3.2.2. Effect of Organic Acid Concentration

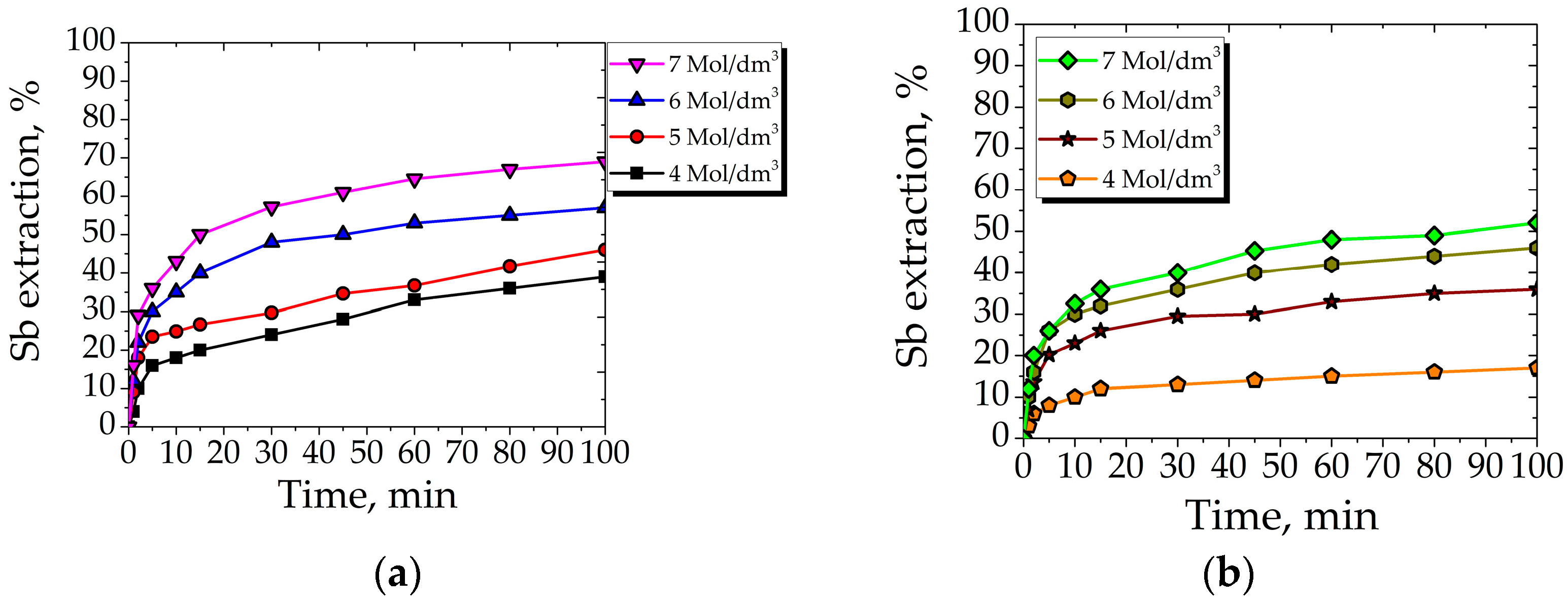

3.2.3. Effect of Nitric Acid Concentration

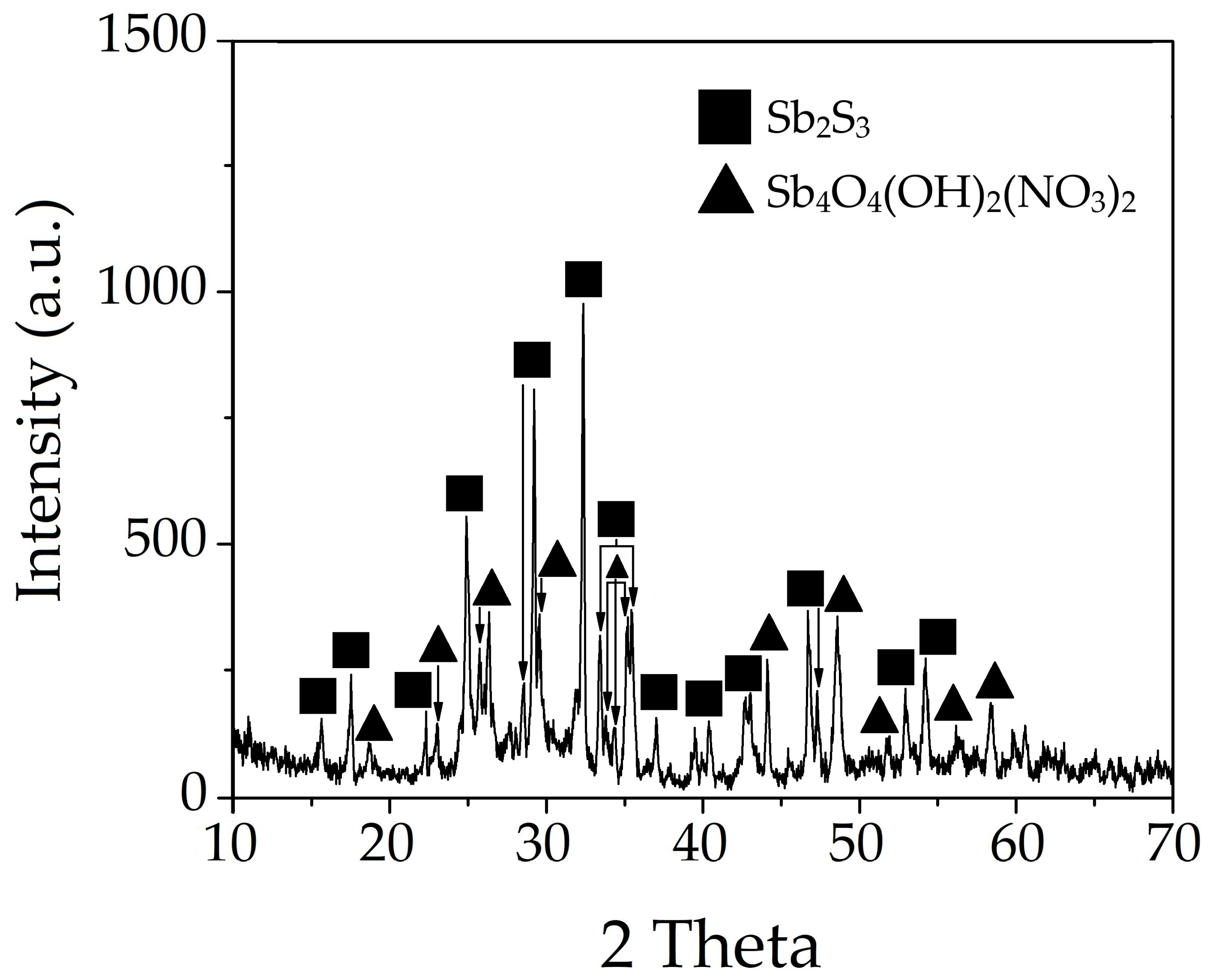

3.3. Characteristics of the Resulting Undissolved Residues

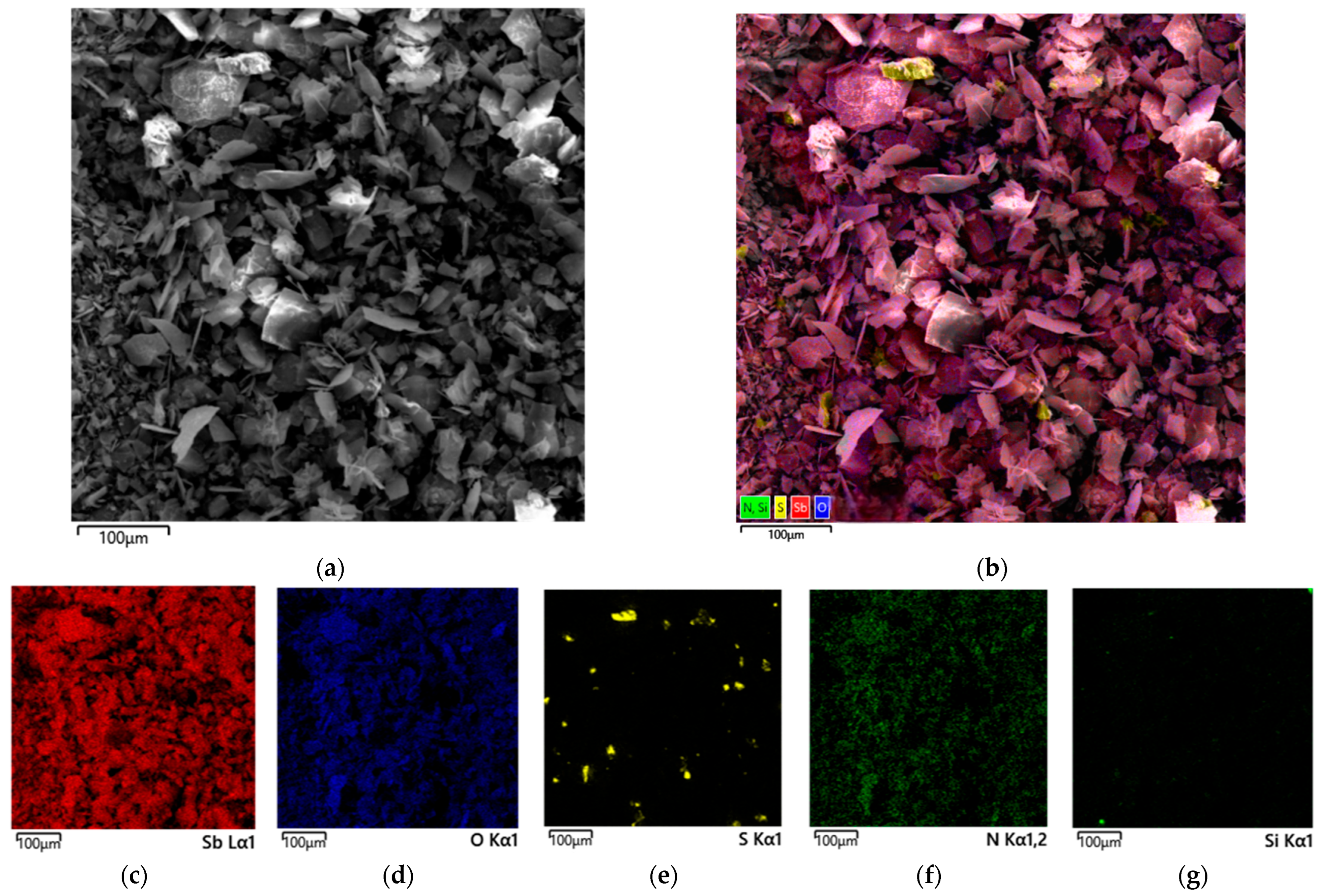

3.3.1. Solid Residue from Nitric Acid Leaching of Stibnite with No Addition of Organic Acids

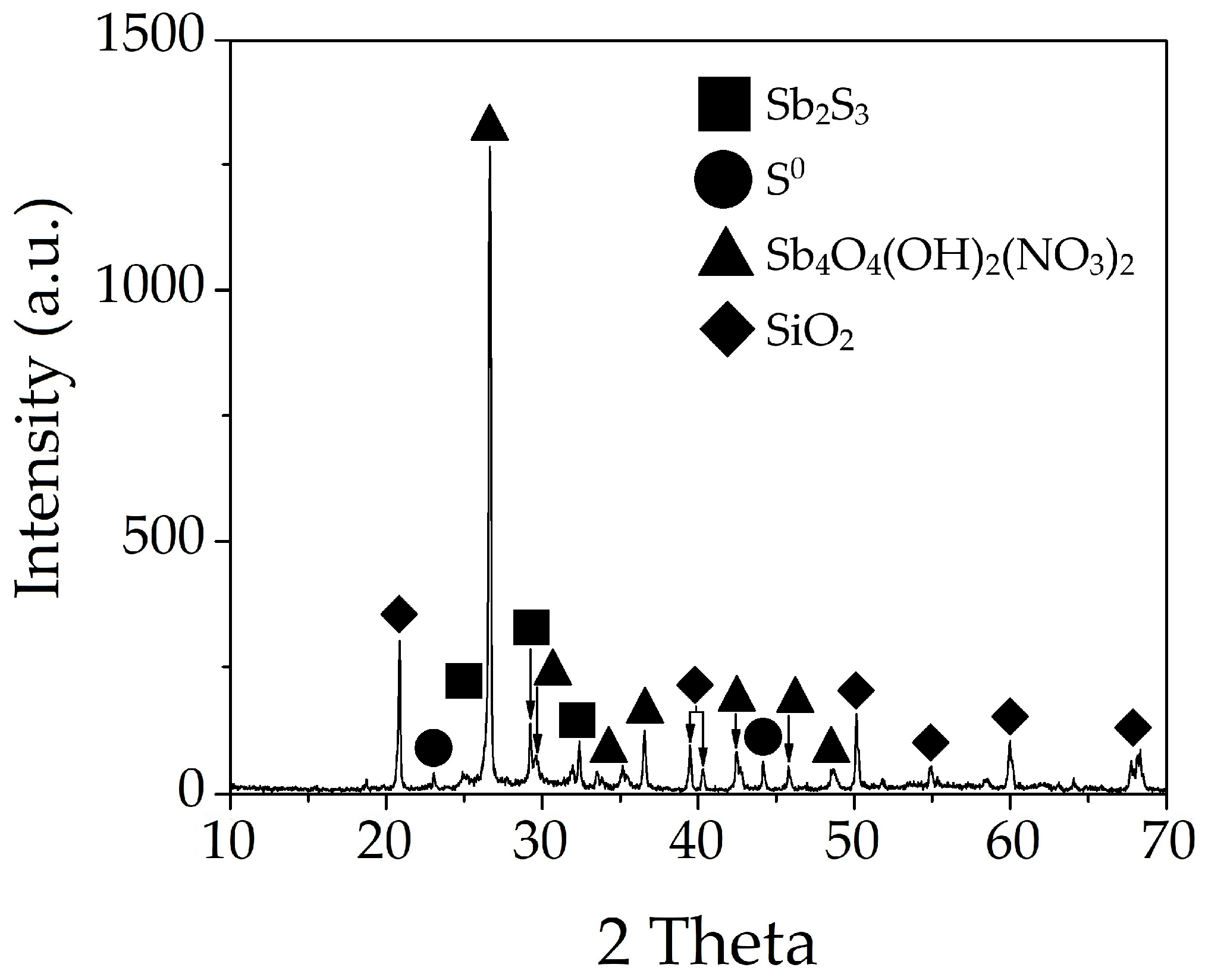

3.3.2. Undissolved Residue from Nitric Acid Leaching of Stibnite with Tartaric Acid Added

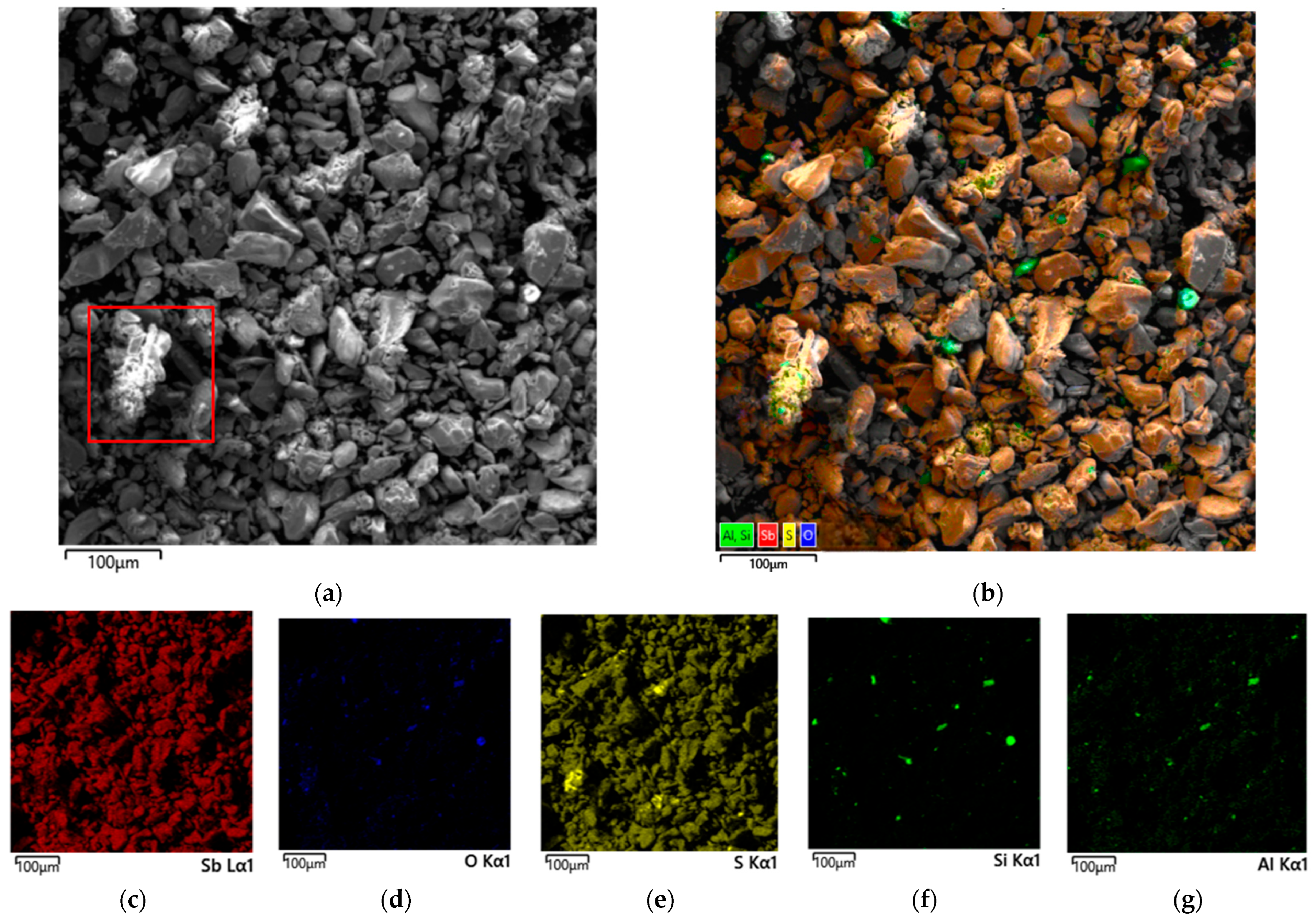

3.3.3. Undissolved Residue from Nitric Acid Leaching of Stibnite with Citric Acid Added

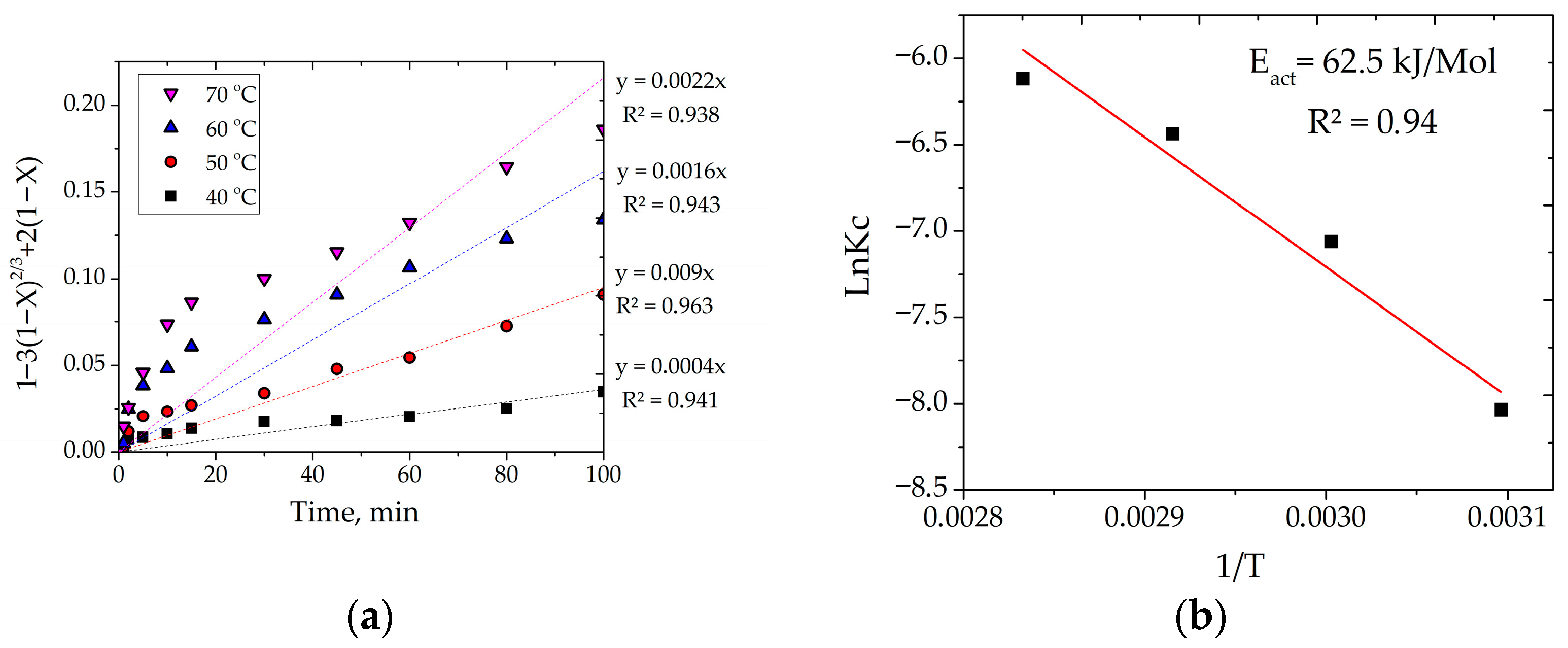

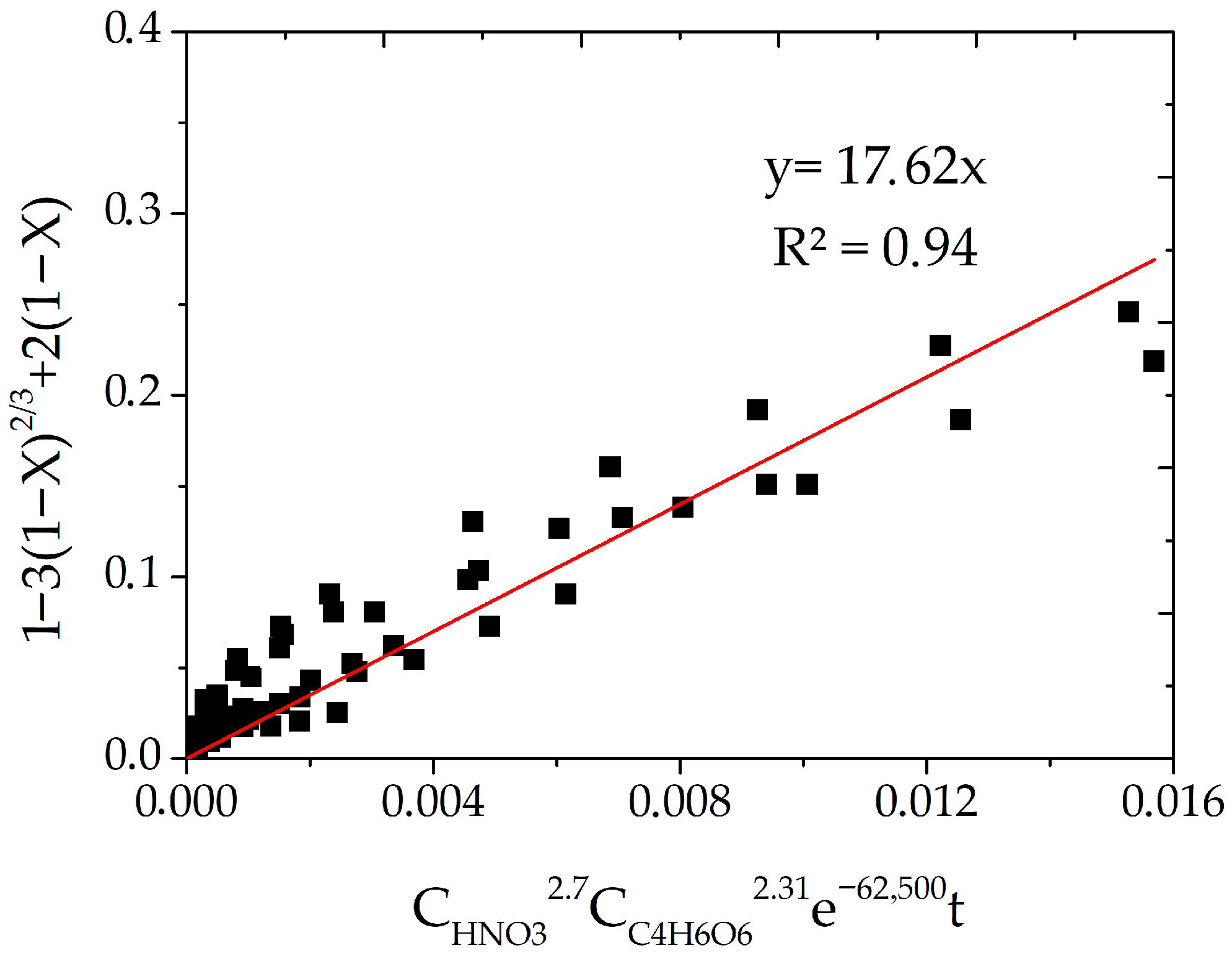

3.4. Calculation of Kinetic Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Tartaric acid proved to be a significantly more effective complexing agent than citric acid. Under optimal conditions, the maximum antimony recovery reached 78%–90% with tartaric acid, compared to only 45%–54% with citric acid. The concentration of organic acids was a critical parameter: increasing the tartaric acid concentration from 20 to 80 g/dm3 boosted antimony recovery from 26% to 76%, whereas the same increase for citric acid only improved recovery from 27% to 56%.

- Phase and morphological analyses (XRD, SEM-EDX) revealed fundamentally different mechanisms. In the absence of organic acids, passivating plate-like Sb4O4(OH)2(NO3)2 particles formed. Tartaric acid effectively prevented the hydrolysis and precipitation of antimony, with the residue containing primarily unreacted stibnite and elemental sulfur, the latter causing passivation at later stages. In contrast, citric acid led to the formation of needle-like Sb4O4(OH)2(NO3)2 particles, indicating insufficient complexation and partial hydrolysis.

- Kinetic studies for the system with tartaric acid established that the process is limited by internal diffusion through a product layer, with an activation energy of 62.5 kJ/mol. The empirical reaction orders were found to be 2.7 for HNO3 and 2.3 for tartaric acid, confirming the complex multi-stage nature of the process where both oxidation and complexation play crucial kinetic roles. A generalized kinetic equation was derived to describe the process adequately.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henckens, M.L.C.M.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Worrell, E. How Can We Adapt to Geological Scarcity of Antimony? Investigation of Antimony’s Substitutability and of Other Measures to Achieve a Sustainable Use. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 108, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, I.; Vithanage, M.; Bundschuh, J. Antimony as a Global Dilemma: Geochemistry, Mobility, Fate and Transport. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Fu, Z. Antimony Pollution in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 421–422, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.G. Hydrometallurgically Treating Antimony-Bearing Industrial Wastes. JOM 2001, 53, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembele, S.; Akcil, A.; Panda, S. Technological Trends, Emerging Applications and Metallurgical Strategies in Antimony Recovery from Stibnite. Miner. Eng. 2022, 175, 107304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multani, R.S.; Feldmann, T.; Demopoulos, G.P. Antimony in the Metallurgical Industry: A Review of Its Chemistry and Environmental Stabilization Options. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 164, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi-Khoonsari, E.; Mostaghel, S.; Siegmund, A.; Cloutier, J.-P. A Review on Pyrometallurgical Extraction of Antimony from Primary Resources: Current Practices and Evolving Processes. Processes 2022, 10, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.N. Synthesis of Potassium Antimony Tartrate from the Antimony Dross of Lead Smelters. Hydrometallurgy 1990, 25, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Idrees Ibrahim, A.; Aboelgamel, M.; Kaan Soylu, K.; Top, S.; Kursunoglu, S.; Altiner, M. Production of High-Grade Antimony Oxide from Smelter Slag via Leaching and Hydrolysis Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikedzi, A.; Sandström, Å.; Awe, S.A. Recovery of Antimony Compounds from Alkaline Sulphide Leachates. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2016, 152, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baláž, P.; Achimovičová, M. Selective Leaching of Antimony and Arsenic from Mechanically Activated Tetrahedrite, Jamesonite and Enargite. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2006, 81, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusalev, R.E.; Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Koblik, A.A. Optimization of Alkaline Sulfide Leaching of Gold-Antimony Concentrates. Mater. Sci. Forum 2020, 989, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muravyov, M. Two-Step Processing of Refractory Gold-Containing Sulfidic Concentrate via Biooxidation at Two Temperatures. Chem. Pap. 2019, 73, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loni, P.C.; Wu, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; H Tuovinen, O. Mechanism of Microbial Dissolution and Oxidation of Antimony in Stibnite under Ambient Conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y. Ferric Chloride Leaching of Antimony from Stibnite. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 186, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusalev, R.; Rogozhnikov, D.; Dizer, O.; Golovkin, D.; Karimov, K. Development of a Two-Stage Hydrometallurgical Process for Gold–Antimony Concentrate Treatment from the Olimpiadinskoe Deposit. Materials 2023, 16, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogozhnikov, D.; Dizer, O.; Karimov, K.; Zakhar’yan, S. Nitric Acid Leaching of the Copper-Bearing Arsenic Sulphide Concentrate of Akzhal. Tsvetnye Met. 2020, 8, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, M.; Pokrovski, G.S. Stability and Structure of Pentavalent Antimony Complexes with Aqueous Organic Ligands. Chem. Geol. 2012, 292–293, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pan, W.; Tong, L.; Hu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Huang, X. Remediation of Sb-Contaminated Soil by Low Molecular Weight Organic Acids Washing: Efficiencies and Mechanisms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; He, M. Organic Ligand-Induced Dissolution Kinetics of Antimony Trioxide. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 56, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Wang, F.; Yan, C.; Tian, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B.; Yuan, R.; Yao, J. Leaching Behavior of Metals from Iron Tailings under Varying pH and Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 383, 121136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodyńska, D.; Burdzy, K.; Hunger, S.; Aurich, A.; Ju, Y. Green Extractants in Assisting Recovery of REEs: A Case Study. Molecules 2023, 28, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tu, T.; Guo, H.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X. High-Efficiency Simultaneous Extraction of Rare Earth Elements and Iron from NdFeB Waste by Oxalic Acid Leaching. J. Rare Earths 2021, 39, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, T.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M. Efficient Inorganic/Organic Acid Leaching for the Remediation of Protogenetic Lead-Contaminated Soil. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, A.B.; Lazarov, M.; Horn, I.; Števko, M.; Ðorđević, T.; Kiefer, S.; Weyer, S.; Majzlan, J. Weathering-Induced Sb Isotope Fractionation during Leaching of Stibnite and Formation of Secondary Sb Minerals. Chem. Geol. 2024, 662, 122253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayotova, M.; Pysmennyi, S.; Panayotov, V. Antimony Recovery from Industrial Residues—Emphasis on Leaching: A Review. Separations 2025, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octave, L. Chemical Reaction Engineering; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; 688p. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, H.; Malfliet, A.; Blanpain, B.; Guo, M. Selective Removal of Arsenic from Crude Antimony Trioxide by Leaching with Nitric Acid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 281, 119976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, R.; Caro, O.; Vega-Garcia, D.; Ruiz, M.C. Mechanism and Kinetics of Stibnite Dissolution in H2SO4-NaCl-Fe(SO4)1.5-O2. Minerals 2022, 12, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaction No. | ΔG, kJ/mol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 40 °C | 55 °C | 70 °C | 85 °C | |

| 2 | −344 | −355 | −367 | −378 | −389 |

| 3 | −1630 | −1683 | −1735 | −1787 | −1839 |

| 4 | −1411 | −1455 | −1498 | −1541 | −1583 |

| 5 | −219 | −228 | −237 | −246 | −255 |

| 6 | −168 | −175 | −182 | −189 | −196 |

| No. | Limiting Phase | Formula | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 °C | 60 °C | 70 °C | 80 °C | |||

| 7 | Diffusion through the product layer (sp) | 1 − 3(1 − X) 2/3 + 2(1 − X) | 0.941 | 0.963 | 0.943 | 0.938 |

| 8 | Diffusion through the product layer (pp) | X2 | 0.909 | 0.89 | 0.901 | 0.911 |

| 9 | Diffusion through the product layer (cp) | X + (1 − X) ln(1 − X) | 0.919 | 0.901 | 0.902 | 0.896 |

| 10 | Diffusion through the liquid film (sp) | X | 0.791 | 0.768 | 0.781 | 0.763 |

| 11 | Surface chemical reaction (cp) | 1 − (1 − X)1/2 | 0.797 | 0.782 | 0.804 | 0.78 |

| 12 | Surface chemical reaction (sp) | 1 − (1 − X)1/3 | 0.799 | 0.787 | 0.813 | 0.792 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dizer, O.; Shklyaev, Y.; Golovkin, D.; Karimov, K.; Rogozhnikov, D. Study of Stibnite Dissolution in Nitric Acid in the Presence of Organic Acids. Minerals 2026, 16, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020125

Dizer O, Shklyaev Y, Golovkin D, Karimov K, Rogozhnikov D. Study of Stibnite Dissolution in Nitric Acid in the Presence of Organic Acids. Minerals. 2026; 16(2):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020125

Chicago/Turabian StyleDizer, Oleg, Yuri Shklyaev, Dmitry Golovkin, Kirill Karimov, and Denis Rogozhnikov. 2026. "Study of Stibnite Dissolution in Nitric Acid in the Presence of Organic Acids" Minerals 16, no. 2: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020125

APA StyleDizer, O., Shklyaev, Y., Golovkin, D., Karimov, K., & Rogozhnikov, D. (2026). Study of Stibnite Dissolution in Nitric Acid in the Presence of Organic Acids. Minerals, 16(2), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020125