Technical and Economic Impact of Geometallurgical Variables in a Mining Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Disclaimer

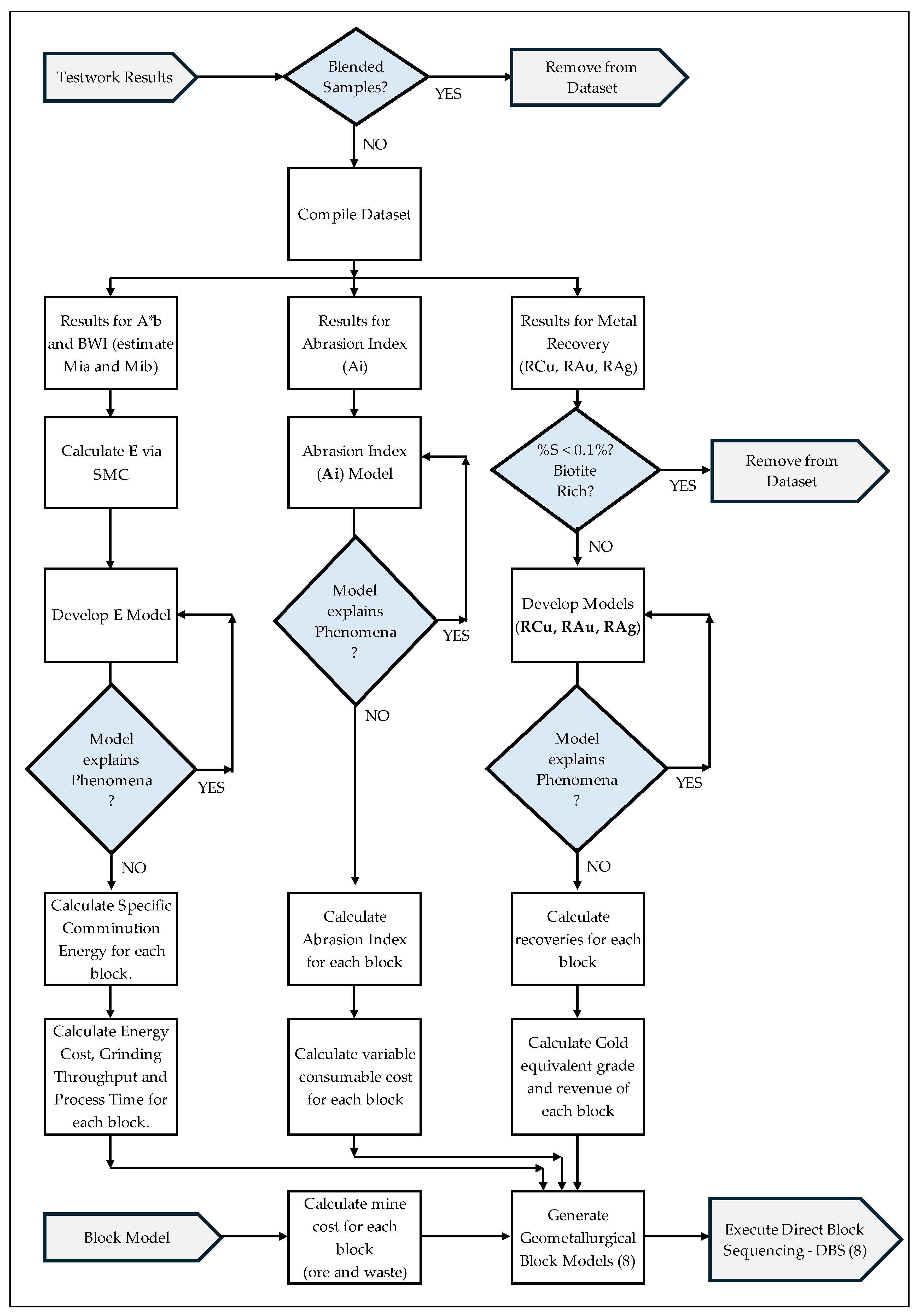

2.2. Overall Study Methodology

2.3. Testwork Results Database

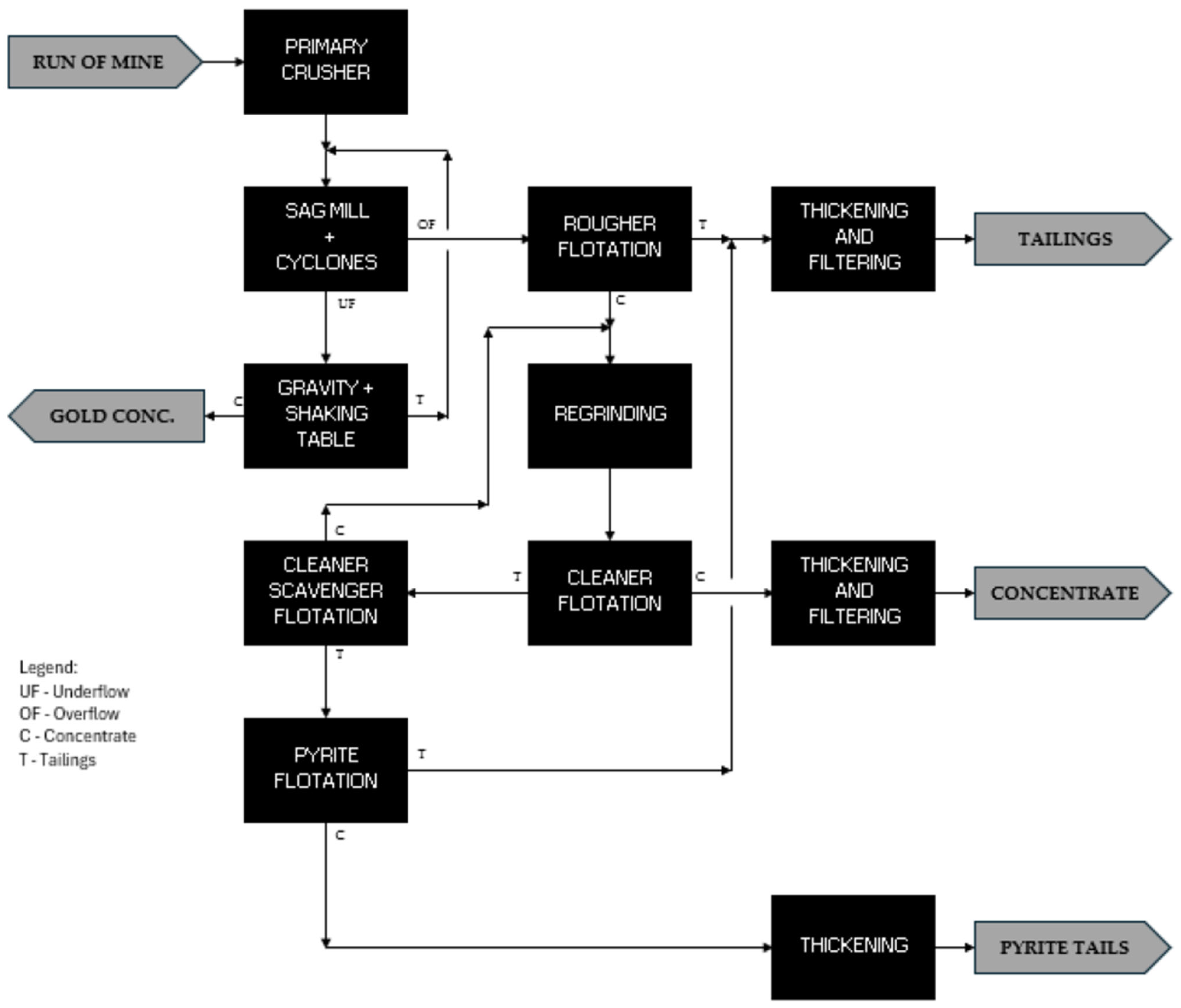

2.4. Process Plant Flowsheet

2.5. Comminution Indices and Specific Energy

2.5.1. SMC Parameters

2.5.2. Bond Ball Mill Work Index

2.5.3. Mia and Mib

2.5.4. Calculation of Specific Energy

2.5.5. Block Throughput and Processing Time

2.6. Geometallurgy Modeling

2.6.1. Specific Comminution Energy (E) Modeling

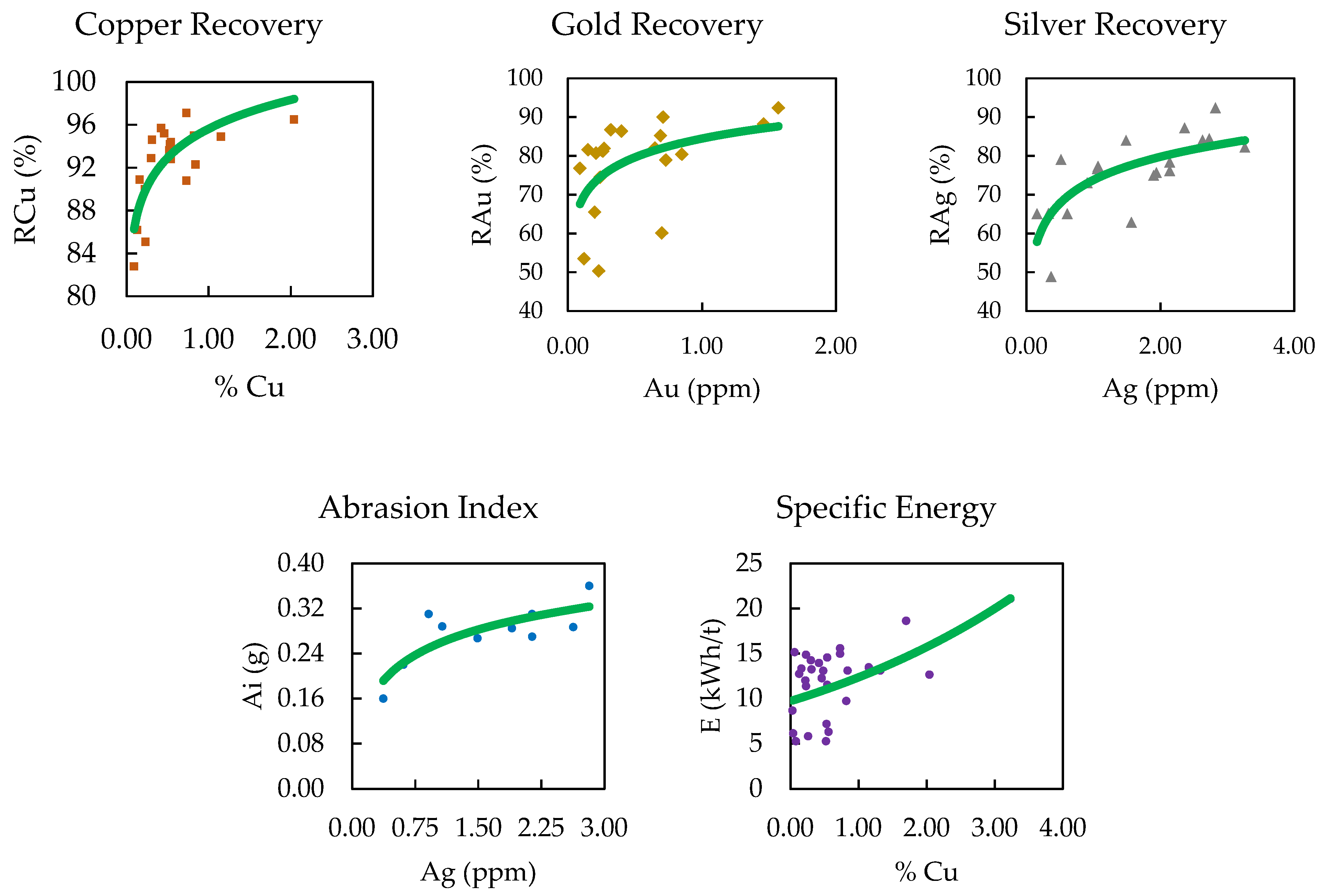

2.6.2. Abrasion Index (Ai) Modeling

2.6.3. Recovery (RCu, RAu, RAg) Modellings

2.7. Gold Equivalent Grade

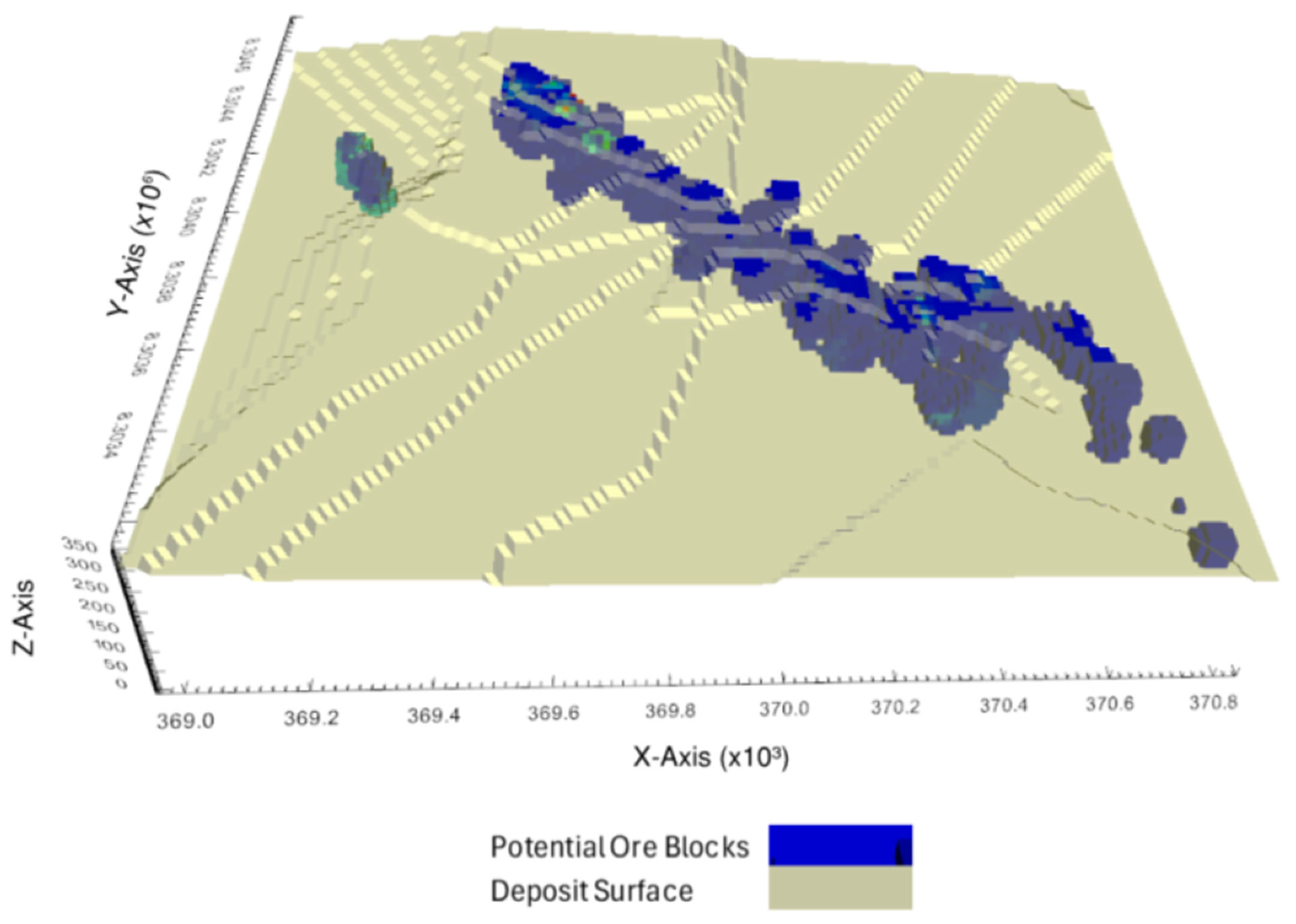

2.8. Deposit’s Block Model

2.9. Block Value Calculations

2.9.1. Revenues

2.9.2. Operating Costs

2.9.3. Block Value

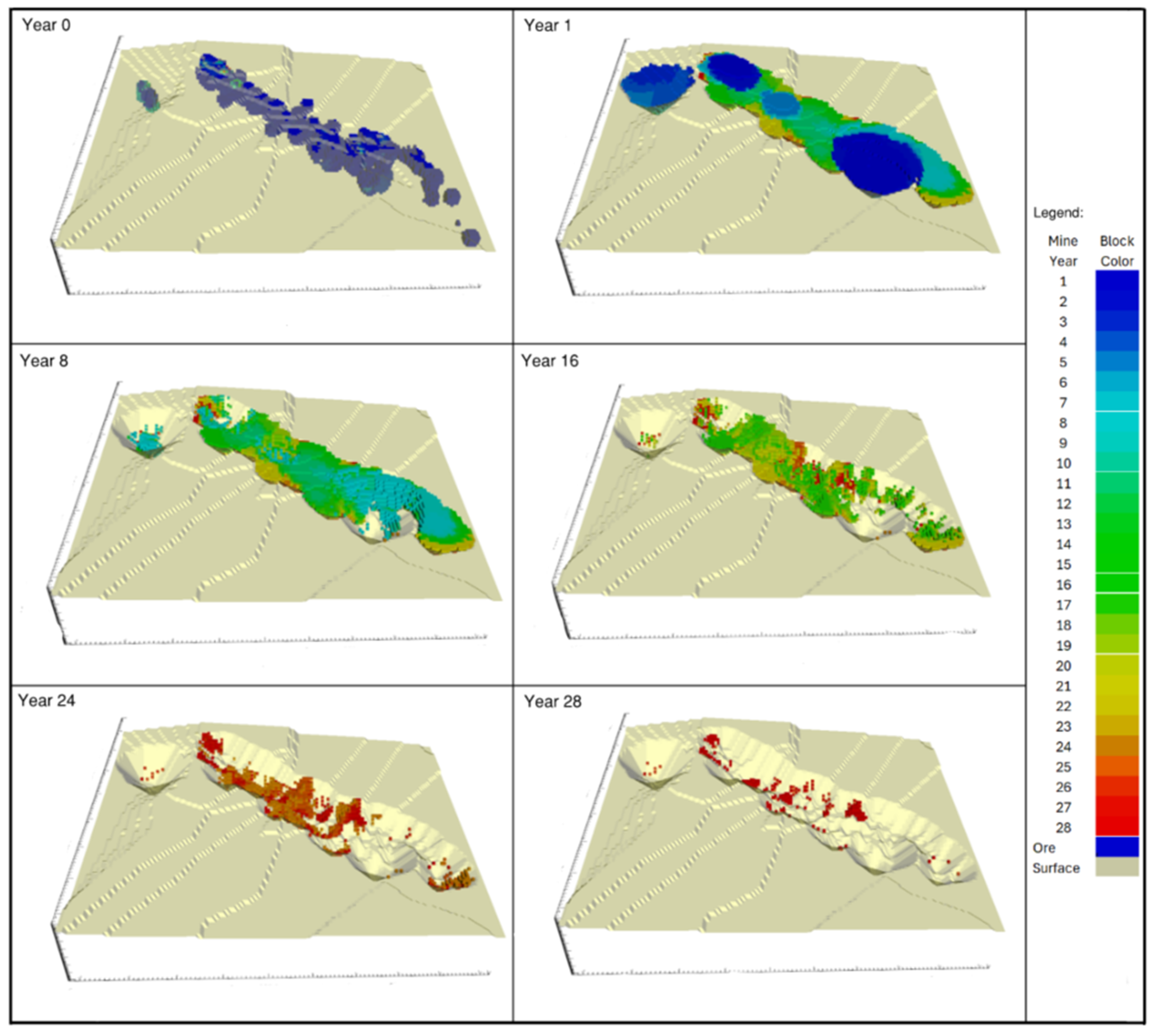

2.10. Direct Block Sequencing

2.10.1. Mine Scheduling Scenarios

2.10.2. Software Used

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Specific Comminution Energy

3.2. Regression Models

3.3. Mine Scheduling Results

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- High-impact variables, when well-modeled, show real NPV potential. For the deposit studied, the variables gold recovery, mine costs, and copper recovery were considered high-impact and responsible for the largest NPV variations obtained.

- Low-impact variables, such as specific comminution energy and abrasion index (related to energy and consumable costs), showed small variations (positive and negative, less than 0.6%) in deposit NPV. Although they did not contribute significantly to the deposit NPV, they were important for (1) identifying NPV stability and trend, and (2) understanding key technical points of the project, such as the potential for equipment selection improvements (e.g., specific energy vs. SAG power) and the understanding that processing time and overall processing plant capacity theoretically will not be exceeded.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, R.d.C.; Ayres da Silva, A.L.M. Assessing Mining Performance Indicators in Relation to the SDGs: Development of a Guided Methodology and Its Application in an Iron Ore Mine. Minerals 2024, 14, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2022; 283p. [Google Scholar]

- Dominy, S.C.; O’Connor, L.; Glass, H.J.; Xie, Y. Geometallurgical Study of a Gravity Recoverable Gold Orebody. Minerals 2018, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishchuk, V.; Koch, P.-H.; Ghorbani, Y.; Butcher, A.R. Towards integrated geometallurgical approach: Critical review of current practices and future trends. Minerals 2020, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebezeit, V.; Ehrig, K.; Robertson, A.; Grant, D.; Smith, M.; Bruyn, H. Embedding geometallurgy into mine planning practices—Practical examples at Olympic Dam. In Proceedings of the Third AusIMM International Geometallurgy Conference 2016, Perth, Australia, 15–17 June 2016; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, M.; Foggiatto, B.; Lane, G. Geometallurgy Applied in Comminution to Minimize Design Risks. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Semi-Autogenous and High-Pressure Grinding Technology (SAG 2015), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–24 September 2015; SAG Conference Foundation: Vancouver, Canada, 2015; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Salas, J.C. Data-Driven Synthesis of a Geometallurgical Model for a Copper Deposit. Processes 2023, 11, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supajaidee, N.; Chutsagulprom, N.; Moonchai, S. An Adaptive Moving Window Kriging Based on K-Means Clustering for Spatial Interpolation. Algorithms 2024, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T. Means and Issues for Adjusting Principal Component Analysis Results. Algorithms 2025, 18, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Hidalgo, M.; Hotchkiss, M.; Dharmasena, L.; Linkov, I.; Fiondella, L. Predictive Resilience Modeling Using Statistical Regression Methods. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholz, W.S.; Schreder, M.L. Escondida—Phase IV Grinding Circuit. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Meeting, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–22 January, 2004; The Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum: Westmount, QC, Canada, 2004; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Amelunxen, P.; Mular, M.A.; Vanderbeek, J.; Hill, L.; Herrera, E. The effects of ore variability on HPGR trade-off economics. In Proceedings of the International Autogenous and Semi-autogenous Grinding and High-Pressure Grinding Roll Technology 2011, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–28 September 2011; Major, K., Flintoff, B.C., Klein, B., McLeod, K., Eds.; University of British Columbia (UBC): Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wirfiyata, F.; McCaffery, K. Applied geo-metallurgical characterization for life of mine throughput prediction at Batu Hijau. In Proceedings of the International Autogenous and Semi-autogenous Grinding and High-Pressure Grinding Roll Technology 2011, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–28 September 2011; Major, K., Flintoff, B.C., Klein, B., McLeod, K., Eds.; University of British Columbia (UBC): Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, L.; Walters, S.G. A Methodology for Geometallurgical Mapping and Orebody Modelling. In Proceedings of the First AusIMM International Geometallurgy Conference 2013, Brisbane, Australia, 30 September–2 October 2013; Dominy, D., Ed.; Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (AusIMM): Carlton, Australia; pp. 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- da Mata, J.F.C.; Nader, A.S.; Mazzinghy, D.B. Inclusion of the geometallurgical variable specific energy in the mine planning using direct block scheduling. Tecnol. Metal. Mater. Min. 2022, 19, e2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Mata, J.F.C.; Nader, A.S.; Mazzinghy, D.B. Methodology to include the comminution specific energy into open-pit strategy mine planning using global optimization. Tecnol. Metal. Mater. Min. 2022, 19, e2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.F.C.D.; Nader, A.S.; Mazzinghy, D.B. A Case Study of Incorporating Variable Recovery and Specific Energy in Long-Term Open Pit Mining. Mining 2023, 3, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Campos, P.; Mazzinghy, D.B. A case study comparing the results of a copper open-pit mine scheduling considering two different approaches for spatial interpolation of comminution geometallurgical variables. J. Sustain. Min. 2025, 24, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, L.V.; Mazzinghy, D.B.; da Silva, G.R.; Seguin, F.; Teixeira, M.F.D.L.; Junior, S.U.F.; Vieira, C.H.R.; Junior, W.F.B.; Silva, V.C.; Dimitrov, G.R. Geometallurgy study of the Catalão I Nelsonite bodies aiming to increase the niobium production. Tecnol. Metal. Mater. Min. 2020, 17, e2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käyhkö, T.; Sinche-Gonzalez, M.; Khizanishvili, S.; Liipo, J. Validation of predictive flotation models in blended ores for concentrator process design. Miner. Eng. 2022, 185, 107685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raponi, T.R.; Elfen, S.C.; Tear, S.; McCartney, J.A.; Soares, L.; Lotter, N.; Lima, J.F.; Rodriguez, P.C. Cabaçal Gold-Copper Project. NI 43-101 Technical Re-Port and Pre-Feasibility Study. 2025. Available online: https://wp-meridianmining-2023.s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/media/2025/04/Cabacal-Project-NI-43-101-Technical-Report-and-PFS_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Raponi, T.R.; Elfen, S.C.; Tear, S.; Batelochi, M.; Keane, J.; Ferreira, G.G. Cabaçal Gold-Copper Project. NI 43-101 Technical Report and Preliminary Economic Assessment. 2023. Available online: https://meridianmining.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Cabacal-NI_43-101-Technical-Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Dominy, S.C.; Glass, H.J. Geometallurgical Sampling and Testwork for Gold Mineralisation: General Considerations and a Case Study. Minerals 2025, 15, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.C. Metal Wear in Crushing and Grinding. Chem. Eng. Prog. 1964, 60, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Doll, A. SMC Test Parameters from BWI. LinkedIn. 2022. Available online: https://ca.linkedin.com/posts/alex-doll-66b57465_workindex-comminution-activity-6935422189697470464-JLCm (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Doll, A. SMC Test Parameters from A × b. LinkedIn 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/alex-doll-66b57465_comminution-grindability-smctest-activity-7152238024792121344-7hB0 (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Morrell, S. Global Trends in Ore Hardness. In Proceedings of the SAG Conference 2015, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–24 September 2015; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell, S. The Morrell Method for Determining Comminution Circuit Specific Energy and Assessing Energy Utilization Efficiency of Existing Circuits. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 416–424. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell, S. An alternative energy–size relationship to that proposed by Bond for the design and optimisation of grinding circuits. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2004, 74, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.C. Crushing and grinding calculations. Min. Eng. 1959, 11, 548–554. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell, S. Predicting SAG/AG Mill and HPGR Specific Energy Requirements Using the SMC Rock Characterisation Test. In Proceedings of the Randol Gold & Silver Forum, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–15 September 2004; Randol International: Perth, Australia, 2004; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzinghy, D.B.; Morales, N.; Brickey, A.; Nelis, G.; Ortiz, J.; Souza, M.J.F. Mineral processing plant capacity based on geometallurgical block model scheduling. In Proceedings of the APCOM Conference 2025: Application of Computers and Operations Research in the Minerals Industry, Perth, Australia, 10–13 August 2025; The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (AusIMM): Carlton, VIC, Australia, 2025; pp. 755–770, ISBN 978-1-922395-50-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, E.; Dowd, P.A.; Xu, C.; Addo, E. Multivariate Modelling of Geometallurgical Variables by Projection Pursuit. Math. Geosci. 2017, 49, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.F.; Magalhães, L.F.; Campos, L.J.F.; Mazzinghy, D.B. Abordagem geometalúrgica aplicada a um novo depósito polimetálico de cobre, ouro e prata na região Centro Oeste do Brasil. In Proceedings of the Anais do 1º Simpósio de Geometalurgia, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 24–25 June 2024; UFMG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2024; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.B. Optimum open pit mine production scheduling. Ph.D. Thesis, Operations Research Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, D.; Goycoolea, M.; Moreno, E.; Newman, A. MineLib: A library of open pit mining problems. Ann. Oper. Res. 2012, 206, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MiningMath®. MiningMath’s Knowledge Base. 2021. Available online: https://knowledge.miningmath.com/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Y. A Branch-and-Price-and-Cut Algorithm for the Inland Container Transportation Problem with Limited Depot Capacity. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Lv, Z.-G.; Wang, J.-B. Branch-and-Bound and Heuristic Algorithms for Group Scheduling with Due-Date Assignment and Resource Allocation. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelvez, E.; Ortiz, J.; Varela, N.M.; Askari-Nasab, H.; Nelis, G. A Multi-Stage Methodology for Long-Term Open-Pit Mine Production Planning under Ore Grade Uncertainty. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, C.; Ljubić, I. Last fifty years of integer linear programming: A focus on recent practical advances. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 324, 707–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, V. Veja Qual é a Taxa Selic Hoje (Abril de 2025). Portal AECweb. 2025. Available online: https://www.aecweb.com.br/revista/noticias/qual-taxa-selic-hoje-esse-mes/24908 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Espínola, F.; Castillo, E.; Orellana, L.F. Bibliometric and PESTEL Analysis of Deep-Sea Mining: Trends and Challenges for Sustainable Development. Mining 2025, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.; Esmaieli, K.; Ordóñez-Calderón, J.C. Application of Data Analytics Techniques to Establish Geometallurgical Relationships to Bond Work Index at the Paracutu Mine, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Minerals 2019, 9, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | Feed Grades | Comminution Indices | Recoveries | Detail | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Au | Ag | A*b | BWI | Ai | Cu | Au | Ag | ||

| % | ppm | ppm | - | kWh/t | g | % | % | % | ||

| CCZ-1 | 1.15 | 1.57 | 2.63 | 39.2 | 11.2 | 0.29 | 94.9 | 92.4 | 84.1 | |

| CCZ-2 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.61 | 41.7 | 8.1 | 0.22 | 90 | 76.8 | 65.1 | |

| CCZ-3 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 1.07 | 47.6 | 9.8 | 0.29 | 94.4 | 82 | 77.3 | |

| ECZ-1 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 1.9 | 35.8 | 15.2 | 0.29 | 90.8 | 74.5 | 75 | |

| ECZ-2 | 0.46 | 0.15 | 2.82 | 42.9 | 9.7 | 0.36 | 95.2 | 81.6 | 92.4 | |

| SCZ-1 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 45 | 8 | 0.16 | 85.1 | 81.9 | 48.9 | |

| SCZ-2 | 0.54 | 0.73 | 2.14 | 33 | 9.7 | 0.27 | 92.8 | 78.9 | 78.4 | |

| CNWE-1 | 0.31 | 0.4 | 0.91 | 42.4 | 12.5 | 0.31 | 94.6 | 86.4 | 73.1 | |

| CNWE-2 | 0.82 | 1.46 | 2.14 | 68.7 | 11.4 | 0.31 | 95 | 88.2 | 76.2 | |

| Zn Comp | 0.84 | 0.26 | 1.49 | 45.5 | 13.7 | 0.27 | 92.3 | 81.2 | 84 | |

| CAB-S1 | 0.52 | 0.85 | 1.57 | 112.7 | 3.6 | - | 93.6 | 80.4 | 62.9 | |

| CAB-S2 | 0.53 | 0.2 | 1.06 | 84.2 | 6.3 | - | 94.2 | 65.5 | 76.7 | |

| CAB-S3 | 0.13 | 0.7 | 0.33 | 37.9 | 7.9 | - | 86.2 | 60.1 | 65.2 | |

| CAB-S4 | 0.16 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 39.1 | 10.7 | - | 90.9 | 85.2 | 79.1 | |

| CAB-S5 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 32.9 | 10.6 | - | 93.8 | 80.2 | 77.1 | Low S |

| CAB-S6 | 0.48 | 3.66 | 2.23 | 40.7 | 11 | - | 95.3 | 65.2 | 71.7 | Low S |

| CAB-S7 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.6 | 33.3 | 11.9 | - | 79.8 | 66.8 | 17 | Low S |

| CAB-S8 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 2.73 | 39.5 | 12.9 | - | 95.7 | 80.7 | 84.4 | |

| CAB-S9 | 0.73 | 0.32 | 2.36 | 35.8 | 13.4 | - | 97.1 | 86.7 | 87.2 | |

| CAB-S11 | 0.04 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 105.8 | 6 | - | 2.8 | 69.3 | 6.1 | Low S |

| CAB-S12 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 1.18 | 102.5 | 6.1 | - | 46.9 | 54.5 | 39.4 | Low S |

| CAB-S13 | 0.08 | 1.69 | 0.72 | 117.1 | 4.1 | - | 2.7 | 83.4 | 29.8 | Low S |

| CAB-S16 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.76 | 123.6 | 6.8 | - | 21.1 | 72 | 32 | Low S |

| CAB-S17 | 1.7 | 0.78 | 10.02 | 32.7 | 21.5 | - | 75.3 | 56.9 | 55 | Biotite Rich |

| CAB-S18 | 3.23 | 0.85 | 16.28 | 28.3 | 24.1 | - | 71.9 | 55.2 | 66.3 | Biotite Rich |

| CAB-S19 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 48.9 | 94 | 82.8 | 50.3 | 65.1 | ||

| CAB-S20 | 2.04 | 0.71 | 3.26 | 41.8 | 10.3 | - | 96.5 | 90 | 82.2 | |

| CAB-S21 | 0.03 | 3.38 | 0.62 | 60.7 | 5.5 | - | 48.5 | 74.8 | 18.5 | Low S |

| CAB-S22 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 1.94 | 34.3 | 9.9 | - | 92.9 | 53.5 | 75.7 | |

| Item | Variable | Equation | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mia | R2 = 1.00 | |

| 2 | Mib | P100 = 105 µm | |

| 3 | P100 = 150 µm | ||

| 4 | P100 = 212 µm | ||

| 5 | P100 = 300 µm |

| Item | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| * Gold Price | 68,129.83 | USD/kg |

| * Copper Price | 9.17 | USD/kg |

| * Silver Price | 864.85 | USD/kg |

| ** Recovery—Cu Refinery | 96.30 | % |

| ** Recovery—Au Refinery | 96.60 | % |

| ** Recovery—Ag Refinery | 90.00 | % |

| Item | Fixed Cost | Variable Cost | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mining (Ore and waste costs) | Drilling, Blasting, Load, Scattering (if applicable) | Transport | Transport cost for ore and waste varies according to Block’s height in relation to process plant. |

| Power Cost | Overall Plant (excluding comminution) | Comminution | Variable cost based on Specific Comminution Energy for each block. |

| Reagents Cost | All reagents | Not applicable | Not applicable in this study |

| Consumable Cost | Filtering clothes | Liners for Crushers and Mills, Grinding Media. | Consumable cost varies according to Abrasion Index for each block. |

| Other items | Labour, Maintenance, Water/Sewage, Access Maintenance, Laboratory, Dry Stacking, General and Administrative (G&A), Concentrate Logistics | Not applicable | As per the original estimate in deposit’s PFS. |

| Scenario | Maximum Block Process Time | Mine Cost | Recoveries | Consumables Cost | Energy Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Variable | Fixed | All Fixed | Fixed | Fixed |

| 2 | Fixed | Fixed | All Fixed | Fixed | Fixed |

| 3 | Fixed | Variable | All Fixed | Fixed | Fixed |

| 4 | Fixed | Variable | Cu—Variable Au—Fixed Ag—Fixed | Fixed | Fixed |

| 5 | Fixed | Variable | Cu—Variable Au—Variable Ag—Fixed | Fixed | Fixed |

| 6 | Fixed | Variable | All Variable | Fixed | Fixed |

| 7 | Fixed | Variable | All Variable | Variable | Fixed |

| 8 | Fixed | Variable | All Variable | Variable | Variable |

| Geometallurgy Variable | Fixed Condition | Variable Condition |

|---|---|---|

| * Block Process Time | 8059 h per year max | Not limited |

| Mine Cost | Ore = 3.63 USD/t | Ore = 2.26 + 0.005464 ∗ (357.5 − Z) USD/t |

| Waste = 3.61 USD/t | Waste = 2.29 + 0.004972 ∗ (357.5 − Z) USD/t | |

| Recoveries | 75th percentile from testwork results Cu Recovery = 94.75% Au Recovery = 81.95% Ag Recovery = 78.75% | As per regression models for each metal |

| Consumables Cost | 1.93 USD/t ore | (0.73 + 1.20 ∗ Block Ai/0.281) USD/t ore |

| Energy Cost | 2.31 USD/t | (1.29 + specific energy ∗ 0.072) USD/t ore |

| Item | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum average Au Eq. grade in ROM (plant feed) | ppm | 1.58 |

| Slope angles (ore and waste blocks) | ° | 48 |

| Max. annual vertical advance rate | m | 60 |

| Discount rate | % | 8 |

| Process Plant throughput | Mtpa | 2.5 |

| Variable | Regression | Model | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper Recovery | Logarithmic | RCu = 3.8904 ln(%Cu) + 95.635 | 0.59 |

| Gold Recovery | Logarithmic | RAu = 6.9989 ln(Au) + 84.461 | 0.23 |

| Silver Recovery | Linear | RAg = 8.6718 ln(Ag) + 73.779 | 0.51 |

| Abrasion Index | Logarithmic | Ai = 0.0648 ln(Ag) + 0.2559 | 0.64 |

| Specific Energy | Exponential | E = 9.7096e0.2414∗%Cu | 0.29 |

| Variable | Exp vs. Regressions | Exp vs. Fixed Value | Exp vs. Opt. Fixed Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper Recovery | 1.25 | 4.56 | 3.38 |

| Gold Recovery | 32.98 | 53.45 | 45.27 |

| Silver Recovery | 14.54 | 38.03 | 33.52 |

| Abrasion Index | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| Specific Energy | 34.84 | 80.35 | 44.31 |

| Variable | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|

| Copper Recovery | If RCu < 82.8% then 82.8% | If RCu > 97.1%, then 97.1% |

| * Gold Recovery | If RAu < 50.3% then 50.3% | If RAu > 92.4%, then 92.4% |

| * Silver Recovery | If RAg < 48.9% then 48.9% | If RAg > 92.4%, then 92.4% |

| Abrasion Index | If Ai < 0.16 then 0.16 | If Ai > 0.36 then 0.36 |

| Specific Energy | If E < 5.26 then 5.26 kWh/t | If E > 21.07 then 21.07 kWh/t |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Freire da Silva, L.; Ferreira, K.C.; Campos, L.J.F.; Mazzinghy, D.B. Technical and Economic Impact of Geometallurgical Variables in a Mining Project. Minerals 2026, 16, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010040

Freire da Silva L, Ferreira KC, Campos LJF, Mazzinghy DB. Technical and Economic Impact of Geometallurgical Variables in a Mining Project. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreire da Silva, Leone, Kelly Cristina Ferreira, Leonardo Junior Fernandes Campos, and Douglas Batista Mazzinghy. 2026. "Technical and Economic Impact of Geometallurgical Variables in a Mining Project" Minerals 16, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010040

APA StyleFreire da Silva, L., Ferreira, K. C., Campos, L. J. F., & Mazzinghy, D. B. (2026). Technical and Economic Impact of Geometallurgical Variables in a Mining Project. Minerals, 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010040