Mechanisms of Gold Enrichment and Precipitation at the Sawayardun Gold Deposit, Southwestern Tianshan, Xinjiang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Deposit Geology

4. Methods

5. Result

5.1. Mineral Structure and Alteration

5.2. Texture of the Arsenopyrite, Pyrite, Stibnite, and Gold

5.2.1. Metamorphosed Sedimentary Period

5.2.2. Hydrothermal Ore-Forming Period

- (1)

- Quartz–Pyrite Stage: This stage represents Phase I of hydrothermal activity, characterized by the formation of short and irregular lenticular quartz veins extending along the strata within the host rock (Figure 4d). The metallic minerals in this stage are almost exclusively pyrite (Py1). Py1 occurs predominantly as coarse-grained euhedral crystals with large particle sizes, exceeding 500 μm and often reaching 1 mm. It exhibits well-developed fractures and pores, with the fractures being infilled by relatively pure quartz grains measuring over 500 μm in size (Figure 4e,f).

- (2)

- Arsenopyrite–Pyrite Stage: This stage represents Phase II of hydrothermal activity, characterized by the occurrence of pyrite–arsenopyrite–quartz veinlets within carbonaceous host rocks (Figure 4g). Pyrite (Py2) and arsenopyrite are distributed within these quartz veinlets, whose widths vary significantly, ranging from a few millimeters to several tens of centimeters. Pyrite (Py2) occurs as anhedral grains with rough and porous surfaces (Figure 4h). The pores are often infilled by arsenopyrite, and the grains are overgrown by later-stage pyrite (Py3). Arsenopyrite (Apy1) exhibits euhedral to subhedral crystal forms, predominantly appearing as rhombohedra, prisms, and needles. The cores of arsenopyrite crystals are porous and are commonly overgrown by later-generation arsenopyrite (Apy2) (Figure 4i). The main gangue minerals are quartz and sericite.

- (3)

- Polymetallic Sulfide Stage: This stage, corresponding to Phases III and IV of hydrothermal activity, constitutes the principal ore-forming episode. It is characterized by metal-bearing quartz veins with widths ranging from 1 to 2 cm (Figure 4j). The sulfide assemblage is dominated by arsenopyrite and pyrite, with subordinate pyrrhotite, chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and stibnite (Figure 4k–m). Native gold is also precipitated during this stage (Figure 4m,n).

- (4)

- Carbonate Stage: This stage represents Phase IV of hydrothermal activity and is characterized by the development of carbonate minerals (Figure 4p). Metallic minerals are sparse, with rarely observed sulfides consisting almost exclusively of pyrite. The pyrite occurring in this stage (Py5) is exceptionally coarse-grained, exceeding 500 μm in size, and forms euhedral crystals with well-developed morphology (Figure 4q). The gangue mineral assemblage, in addition to quartz and sericite, contains abundant calcite (Figure 4r).

5.3. Chemical Composition of Arsenopyrite, Pyrite, Stibnite, and Gold

6. Discussion

6.1. Physicochemical Conditions of Mineralization

6.2. Occurrence Modes of Gold

6.3. Gold Enrichment and Precipitation Mechanisms

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The Sawayardun gold deposit has experienced a metamorphosed sedimentary period and a hydrothermal ore-forming period. The hydrothermal ore-forming period is further divided into four stages: quartz–pyrite stage, arsenopyrite–pyrite stage, polymetallic sulfide stage, and carbonate stage. The ore-forming fluids were characterized as S-rich, As-poor, and relatively reduced.

- (2)

- Gold in the Sawayaerdun deposit occurs in both visible and invisible forms. Visible gold, primarily as native gold, is hosted within and along fractures of sulfides or quartz. Invisible gold mainly exists as gold that can be observed at the micron-to-nanometer scale (Au0) in pyrite and solid solution (Au+) in arsenopyrite.

- (3)

- The adsorption effect of As, the substitution of elements, the dissolution and reprecipitation (CDR) process, and the extraction of the LMCE melt all work together to dominate the enrichment and precipitation of gold in the Sawayardun gold mine.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, C.J.; Zhao, X.B.; Zhang, G.Z.; Mo, X.X.; Gu, X.X.; Dong, L.H.; Zhao, S.M.; Mi, D.J.; Nurtaev, B.; Pak, N.; et al. Metallogenic environments, ore-forming types and prospecting potential of Au-Cu-Zn-Pb resources in Western Tianshan Mountains. China Geol. 2015, 42, 381–410, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Groves, D.I.; Goldfarb, R.J.; Gebre-Mariam, M.; Hagemann, S.G.; Robert, F. Orogenic gold deposits: A proposed classification in the context of their crustal distribution and relationship to other gold deposit types. Ore Geol. Rev. 1998, 13, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, R.; Groves, D. Orogenic gold: Common or evolving fluid and metal sources through time. Lithos 2015, 233, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biske, Y.S.; Seltmann, R. Paleozoic Tian-Shan as a transitional region between the Rheic and Urals-Turkestan oceans. Gondwana Res. 2010, 17, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J.; Song, D.F.; Windley, B.F.; Li, J.L.; Han, C.M.; Bo, W.; Zhang, J.E.; Ao, S.J.; Zhang, Z.Y. Accretionary processes and metallogenesis of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Advances and perspectives. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 329–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, P.L.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Peng, N.H.; Fu, H.; Yang, G.X. Genesis of the Katbasu gold deposit in the western Tianshan, NW China: Constraints from fluid inclusions and H-O, S, and Pb isotopes. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2025, 294, 106819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhem, C.; Windley, B.F.; Stampfli, G.M. The Altaids of Central Asia: A tectonic and evolutionary innovative review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2012, 113, 303–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.X.; He, Z.Y.; Liang, Y.; Song, S.D.; Johan, D.G.; Zhu, W.B.; Tong, H.F.; Bakhiter, N.; Zhong, L.L.; Li, C.L.; et al. Mesozoic−Cenozoic source provenance and thermal evolution of the southwestern Tien Shan, SE Uzbekistan. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2025, 138, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, R.J.; Taylor, R.D.; Collins, G.S.; Goryachev, N.A.; Orlandini, O.F. Phanerozoic continental growth and gold metallogeny of Asia. Gondwana Res. 2014, 25, 48–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.J.; Zhao, X.B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W.C.; Mo, X.X.; Xiao, W.J.; Ma, H.D.; Zhu, B.Y.; Pak, N.; Nurtaev, B.; et al. Early Permian Au-Ni major metallogenic events in western Central Asian metallogenic domain. Miner. Depos. 2024, 43, 749–784. [Google Scholar]

- Frimmel, H.E. Earth’s continental crustal gold endowment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 267, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloviev, S.G.; Kryazhev, S.G.; Seltmann, R. Geochemical fingerprints of the late Palaeozoic igneous rocks at the giant Muruntau gold deposit (Tien Shan, Uzbekistan) and implications for a metallogenic model. Int. Geol. Rev. 2025, 67, 2613–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.W.; Dmitry, K.; Reimar, S.; Bernd, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.T.; Olav, E.; Toorat, U. Postcollisional Age of the Kumtor Gold Deposit and Timing of Hercynian Events in the Tien Shan, Kyrgyzstan. Econ. Geol. 2004, 99, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asilbekov, K.; Orozbaev, R.; Skrzypek, E.; Hauzenberger, C.; Ivleva, E.; Gallhofer, D.; Gao, J.F.; Pak, N.; Shevkunov, A.; Bashkirov, A.; et al. Age and Petrogenesis of the newly Discovered Early Permian Granite in the Kumtor Gold Field, Kyrgyz Tien-Shan. J. Earth Sci. 2025, 36, 1090–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierlein, F.P.; Wilde, A.R. New constraints on the polychronous nature of the giant Muruntau gold deposit from wall-rock alteration and ore paragenetic studies. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2010, 57, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Z.; Xue, C.J.; Chi, G.X.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhao, X.B.; Zu, B.; Zhao, Y. Multiple-stage mineralization in the Sawayaerdun orogenic gold deposit, western Tianshan, Xinjiang: Constraints from paragenesis, EMPA analyses, Re–Os dating of pyrite (arsenopyrite) and U–Pb dating of zircon from the host rocks. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 81, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.J.; Zhao, X.B.; Zhao, W.C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.Z.; Nurtaev, B.; Pak, N.; Mo, X.X. Deformed zone hosted gold deposits in the China-Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Tien Shan: Metallogenic environment, controlling parameters, and prospecting criteria. Earth Sci. Front. 2020, 27, 294–319, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.H.; Ye, Q.T.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.P.; Yang, F.Q.; Fu, X.J. Geology, Geochemistry, and Metallogenesis of the Sawayaerdun Gold (-Antimony) Deposit. Miner. Depos. 1999, 66–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Ni, P.; Zhang, Z.J. Fluid inclusion study of the Sawayardun Au deposit in southern Tianshan, China:implication for ore genesis and exploration. Miner. Petrol. 2004, 24, 46–54, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Ni, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.J. Chemical composition of fluid inclusions of the Sawayardun gold deposit, Xinjiang:Implications for oregenesis and prediction. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2007, 23, 2189–2197, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.J.; Chen, Z.L.; Zhang, W.G.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Han, F.B.; Huo, H.L.; Yang, B.; Ma, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Structural deformation and fluid evolution associated with the formation of the Sawayardun gold deposit in Southwestern Tianshan Orogen. China Geol. 2022, 49, 181–200, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.H.; Liu, J.J.; Long, X.R.; Zhang, S.T.; Song, X.Y. Geochemical Characteristics of the Sawaya’erdun Gold Deposit in the Southwestern Tianshan Mountains. Bull. Mineral. Petrol. Geochem. 2000, 226–227, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Preliminary study of the sources of ore-forming minerals of shawayaerdun gold deposit. Xinjiang Geol. 2001, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.D. Source of Mineralized Substances and Ore-Forming Mechanism of Xinjiang Sawayaerdun Murantau-Type Gold Deposits; Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Institute of Geochemistry): Guiyang, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Baker, M.J. Evolution of ore-forming fluids in the Sawayaerdun gold deposit in the Southwestern Chinese Tianshan metallogenic belt, Northwest China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 49, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Q.; Mao, J.; Wang, Y.T.; Li, M.W.; Ye, H.S.; Ye, J.H. Geological characteristics and metallogenesis of Sawayaerdun gold deposit in southwest Tianshan Mountains, Xinjiang. Miner. Depos. 2005, 24, 206–227, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.S.; Wang, S.Y.; Deng, S.L. Typomorphic minerals characteristics of the Sawaya’erdun gold deposit and the distribution with enriching rules of the gold, Xinjiang. Miner. Resour. Geol. 2008, 22, 391–395, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Charvet, J.; Shu, L.; Laurent Charvet, S.; Wang, B.; Michel, F.; Dominique, C.; Chen, Y.; Koen, D.J. Palaeozoic tectonic evolution of the Tianshan belt, NW China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2011, 54, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Y.; Frederik, T.; Yuan, X.H.; Andreas, R.; Sofia-Katerina, K.; Li, W.; Bernd, S.; Andreas, F. Unraveling the Mantle Dynamics in Central Asia with Joint Full Waveform Inversion. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2025, 130, e2024JB030061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.L.; Wang, W.T.; Zhang, P.Z.; Wang, Y.; Pang, J.Z.; Zhang, Y.P.; Li, Z.G.; Yan, Y.G.; Zhang, H.P.; Zheng, D.W. Multi-Stage Uplift and Propagation of the Chinese East Tianshan During the Cenozoic. Tectonics 2025, 44, e2024TC008666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Natal’in, B.A.; Burtman, V.S. Evolution of the Altaid tectonic collage and Palaeozoic crustal growth in Eurasia. Nature 1993, 364, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.L.; Wang, Z.Z.; Han, F.B.; Zhang, W.G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Z.J.; Wang, X.H.; Xiao, W.F.; Han, S.Q.; Yu, X.Q.; et al. Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic uplift, deformation, and erosion of the SW Tianshan Mountains in Kyrgyzstan and Western China. Int. Geol. Rev. 2018, 60, 1019–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.L.; Chen, Z.L.; Zhang, Q.; Han, F.B.; Zhang, W.G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.B. Early Paleozoic Tectonic Evolution of the Chinese Southwest Tianshan Orogen: Implications from Detrital Zircon U-Pb Geochronology of the Biedieli Sedimentary Rocks, Northern Wushi Area, NW China. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. 2025, 99, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windley, B.F.; Alexeiev, D.; Xiao, W.J.; Kroöner, A.; Badarch, G. Tectonic models for accretion of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. Soc. London 2007, 164, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; He, D.F.; Tang, Y.; Wu, X.Z.; Lian, Y.C.; Yang, Y.H. Dynamic processes from plate subduction to intracontinental deformation: Insights from the tectono-sedimentary evolution of the Zhaosu–Tekesi Depression in the southwestern Chinese Tianshan. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 113, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voute, F.; Hagemann, S.G.; Evans, N.J.; Villanes, C. Sulfur isotopes, trace element, and textural analyses of pyrite, arsenopyrite and base metal sulfides associated with gold mineralization in the Pataz-Parcoy district, Peru: Implication for paragenesis, fluid source, and gold deposition mechanisms. Minim. Depos. 2019, 54, 1077–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, J.A.; Large, R.R.; Olin, P.H.; Danyushevsky, L.V.; Meffre, S.; Huston, D.; Fabris, A.; Lisitsin, V.; Wells, T. Pyrite trace element behavior in magmatic-hydrothermal environments: An LA-ICPMS imaging study. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 128, 103878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

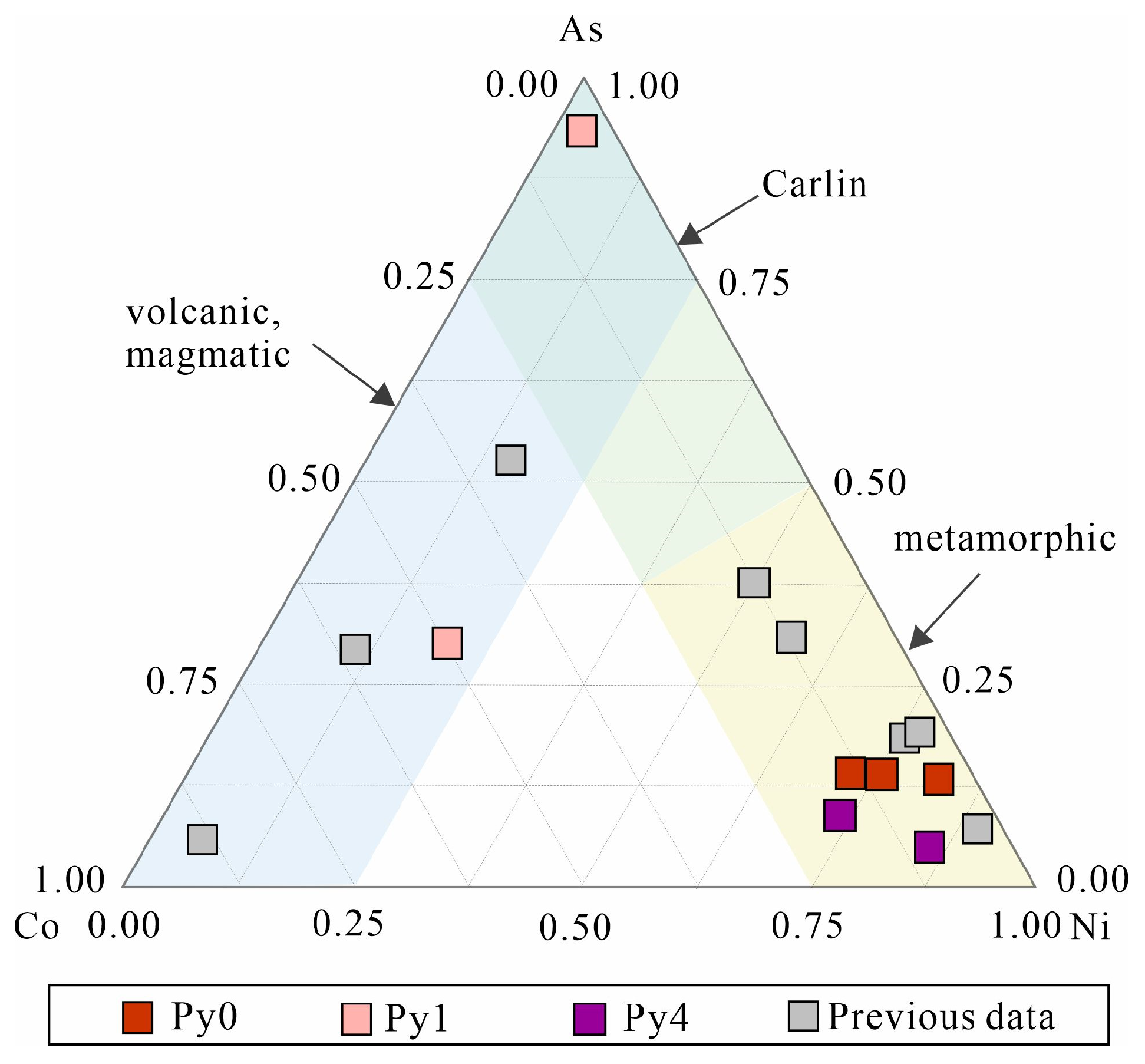

- Bralia, A.; Sabatini, G.; Troja, F. A revaluation of the Co/Ni ratio in pyrite as geochemical tool in ore genesis problems. Minim. Depos. 1979, 14, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Grguric, B.; Mumm, A.S. Genetic implications of pyrite chemistry from the Palaeoproterozoic Olary Domain and overlying Neoproterozoic Adelaidean sequences, northeastern South Australia. Ore Geol. Rev. 2004, 25, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.Y. Trace elements in pyrite from orogenic gold deposits: Implications for metallogenic mechanism. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2023, 39, 2330–2346, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.T.; Li, S.R.; Jia, B.J.; Zhang, N.; Yan, L.N. Composition typomorphic characteristics and statistic analysis of pyrite in gold deposits of different genetic types. Earth Sci. Front. 2012, 19, 214–226, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Xiao, Z.B.; Fu, C.; Fu, S.X.; Zhu, Z.M. Genetic Mineralogy and Geological Significance of Gold Minerals and Gold-bearing Pyrites from the Xinli Gold Deposit in the Jiaodong Area. Rock Miner. Anal. 2022, 41, 997–1006, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.Z.; Xue, C.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhao, X.B.; Feng, C.R.; Meng, B.D. The ore-forming process of the Sawayaerdun gold deposit, western Tianshan, Xinjiang: Contraints from the generation relationship and EMPA, LA-ICPMS and FESEM analysis of the Pyrite and Arsenopyrite. Geol. China 2022, 49, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; LÜ, X.B.; Yang, S.; Xiao, Q.; Li, J.; Ren, L. Typomorphic characteristics of pyrites in the Pangjiahe gold deposit, Shaanxi Province and indication for deep ore prospecting. China Geol. 2023, 50, 277–288, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Keith, M.; Smith, D.J.; Doyle, K.; Holwell, D.A.; Jenkin, G.R.T.; Barry, T.L.; Becker, J.; Rampe, J. Pyrite chemistry: A new window into Au-Te ore-forming processes in alkaline epithermal districts, Cripple Creek, Colorado. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 274, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Q.; Mao, J.W.; Wang, Y.T.; Bierlein, F.P.; ShouYe, H.; Li, M.W.; Zhao, C.S.; Ye, J. Geology and Metallogenesis of the Sawayaerdun Gold Deposit in the Southwestern Tianshan Mountains, Xinjiang, China. Resour. Geol. 2007, 57, 57–75, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.F.; Qiu, K.F.; He, D.Y.; Huang, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.X.; Fu, N.; Yu, H.C.; Xue, X.F. Mineralogy and geochemistry of gold-bearing sulfides in the Wanken gold deposit West Qinling Orogen. Earth Sci. Front. 2023, 30, 371–390, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Wu, C.; Li, H.B.; Shah, S.A. Geochemical Characteristics of Chlorite from the Chaxi Gold Deposit in Southwestern Hunan, Jiangnan Orogenic Belt:Implications on Ore Genesis. Geotecton. Metallog. 2023, 47, 598–617. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Deng, T.; Xu, D.R.; Lin, Y.F.; Liu, G.F.; Tang, H.M.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J. Genetic association between carbonates and gold precipitation mechanisms in the Jinshan deposit, eastern Jiangnan orogen. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2024, 136, 4195–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabri, L.J.; Chryssoulis, S.L.; de Villiers, J.P.R.; Laflamme, J.H.G.; Buseck, P.R. The nature of “invisible” gold in arsenopyrite. Can. Mineral. 1989, 27, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, N.J.; Chryssoulis, S.L. Concentrations of invisible gold in the common sulfides. Can. Mineral. 1990, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, M.; Kesler, S.E.; Utsunomiya, S.; Palenik, C.S.; Chryssoulis, S.L.; Ewing, R.C. Solubility of gold in arsenian pyrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 2781–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deditius, A.P.; Reich, M.; Kesler, S.E.; Utsunomiya, S.; Chryssoulis, S.L.; Walshe, J.; Ewing, R.C. The coupled geochemistry of Au and As in pyrite from hydrothermal ore deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 140, 644–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Bowell, R.J.; Migdisov, A.A. Gold in Solution. Elements 2009, 5, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seward, T.M. Thio complexes of gold and the transport of gold in hydrothermal ore solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1973, 37, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.R.; Mavrogenes, J.A. Gold Solubility in Supercritical Hydrothermal Brines Measured in Synthetic Fluid Inclusions. Science 1999, 284, 2159–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, B.R.; Mavrogenes, J.A.; Tomkins, A.G. Partial melting of sulfide ore deposits during medium-and high-grade metamorphism. Can. Mineral. 2002, 40, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Qi, C.; Du, Z.Z.; Zhang, H.K.; Wang, S.C.; Wang, H.S.; Yu, J.T.; Li, L. Decoding the driving mechanisms of high-grade gold enrichment in the Jiaodong Peninsula: Insights from episodic releases of gold-rich fluids in the Jinqingding deposit. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 187, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Zhai, D.G.; Wang, D.Z.; Gao, S.; Yin, C.; Liu, Z.J.; Wang, J.P.; Wang, Y.H.; Zhang, F.F. Classification and mineralization of the Au-(Ag)-Te-Se deposits. Earth Sci. Front. 2020, 27, 79–98, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.F.; Fougerouse, D.; Evans, K.; Reddy, S.M.; Saxey, D.W.; Guagliardo, P.; Li, J.W. Gold, arsenic, and copper zoning in pyrite: A record of fluid chemistry and growth kinetics. Geology 2019, 47, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Huang, F.; Gao, W.Y.; Gao, R.Z.; Zhao, F.D.; Zhou, Y.R.; Li, Y.L. Multi-Step Gold Refinement and Collection Using Bi-Minerals in the Laozuoshan Gold Deposit, NE China. Minerals 2022, 12, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Wan, Q.; Hochella, M.F.; Luo, S.; Yang, M.; Li, S.; Fu, Y.; Zeng, P.; Qin, Z.; Yu, W. Interfacial adsorption of gold nanoparticles on arsenian pyrite: New insights for the transport and deposition of gold nanoparticles. Chem. Geol. 2023, 640, 121747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopon, P.; Douglas, J.O.; Auger, M.A.; Hansen, L.; Wade, J.; Cline, J.S.; Robb, L.J.; Moody, M.P. A Nanoscale Investigation of Carlin-Type Gold Deposits: An Atom-Scale Elemental and Isotopic Perspective. Econ. Geol. 2019, 114, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E.; Mumin, A.H. Gold-bearing arsenian pyrite and marcasite and arsenopyrite from Carlin Trend gold deposits and laboratory synthesis. Am. Mineral. 1997, 82, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, I.A.; Xia, F.; Deditius, A.P.; Pearce, M.A.; Roberts, M.P.; Brugger, J. A new mode of mineral replacement reactions involving the synergy between fluid-induced solid-state diffusion and dissolution-reprecipitation: A case study of the replacement of bornite by copper sulfides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2022, 330, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricio-Silva, W.; Schutesky, M.E.; Frimmel, H.E.; Fougerouse, D.; Rosière, C.A.; Caxito, F.A.; Bosco-Santos, A. Is there a specific “timing of mineralization” in gold deposits? Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 182, 106663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkins, A.G.; Pattison, D.R.M.; Frost, B.R. On the Initiation of Metamorphic Sulfide Anatexis. J. Petrol. 2007, 48, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwell, D.A.; Fiorentini, M.; McDonald, I.; Lu, Y.J.; Giuliani, A.; Smith, D.J.; Keith, M.; Locmelis, M. A metasomatized lithospheric mantle control on the metallogenic signature of post-subduction magmatism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooth, B.; Brugger, J.; Ciobanu, C.; Liu, W.H. Modeling of gold scavenging by bismuth melts coexisting with hydrothermal fluids. Geology 2008, 36, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Wang, D.Z.; Zhai, D.G.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, B.; Gao, S.; Zhong, R.C.; Zhao, S.J. Super-enrichment mechanisms of precious metals by low-melting point copper-philic element(LMCE) melts. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2021, 37, 2629–2656, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, W.; Meng, L.; Ding, J.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Hou, X.; Yu, W. Mechanisms of Gold Enrichment and Precipitation at the Sawayardun Gold Deposit, Southwestern Tianshan, Xinjiang, China. Minerals 2026, 16, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010039

Ding W, Meng L, Ding J, Li S, Yang X, Hou X, Yu W. Mechanisms of Gold Enrichment and Precipitation at the Sawayardun Gold Deposit, Southwestern Tianshan, Xinjiang, China. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Weiyu, Lin Meng, Jiangang Ding, Shengtao Li, Xiuzhi Yang, Xiaoyi Hou, and Wenjie Yu. 2026. "Mechanisms of Gold Enrichment and Precipitation at the Sawayardun Gold Deposit, Southwestern Tianshan, Xinjiang, China" Minerals 16, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010039

APA StyleDing, W., Meng, L., Ding, J., Li, S., Yang, X., Hou, X., & Yu, W. (2026). Mechanisms of Gold Enrichment and Precipitation at the Sawayardun Gold Deposit, Southwestern Tianshan, Xinjiang, China. Minerals, 16(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010039