Micro-XRF-Based Quantitative Mineralogy of the Beauvoir Li Granite: A Tool for Facies Characterization and Ore Processing Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

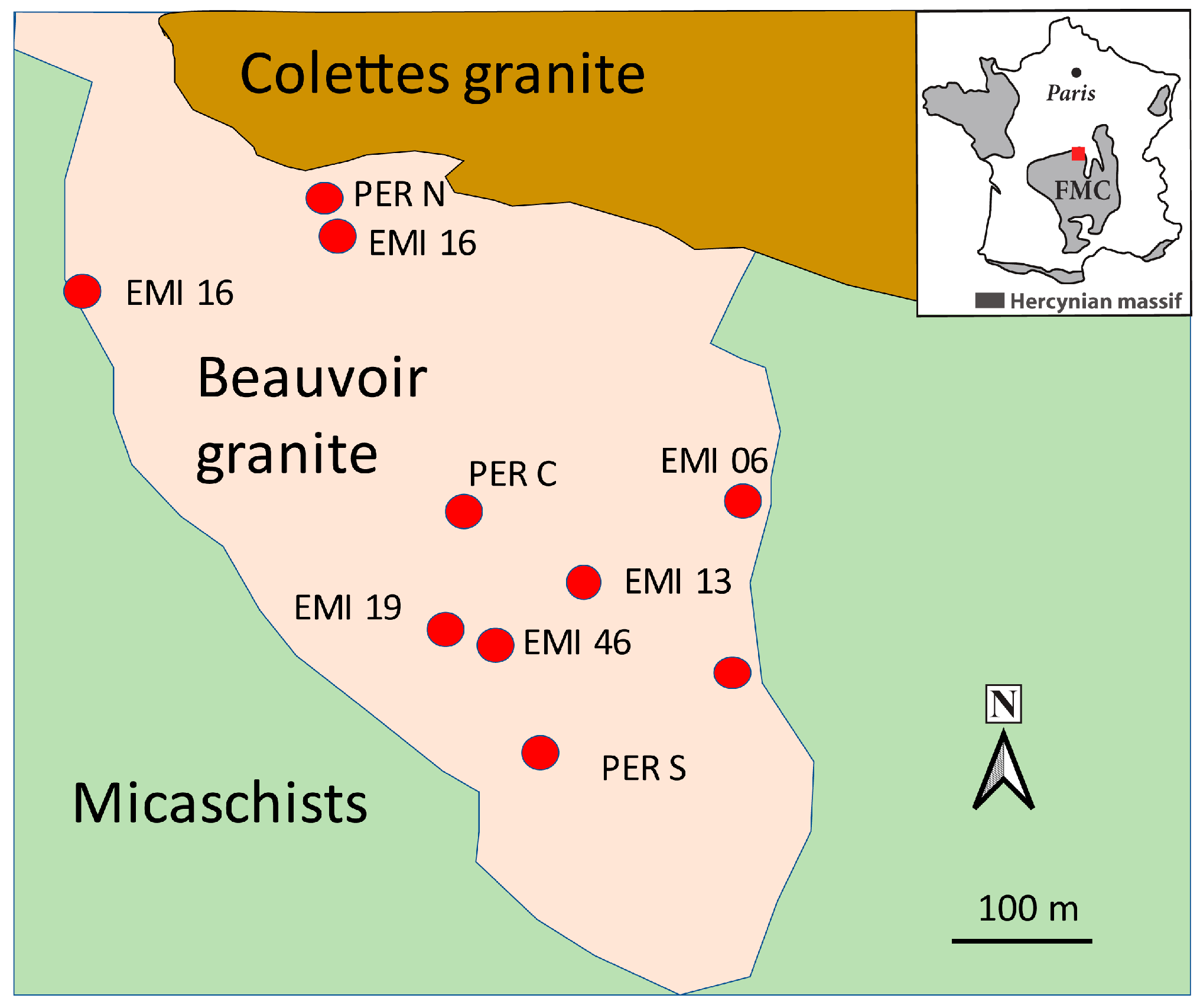

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Micro X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry

2.3. Normative Mineral Calculation with GeoRunes

3. Results

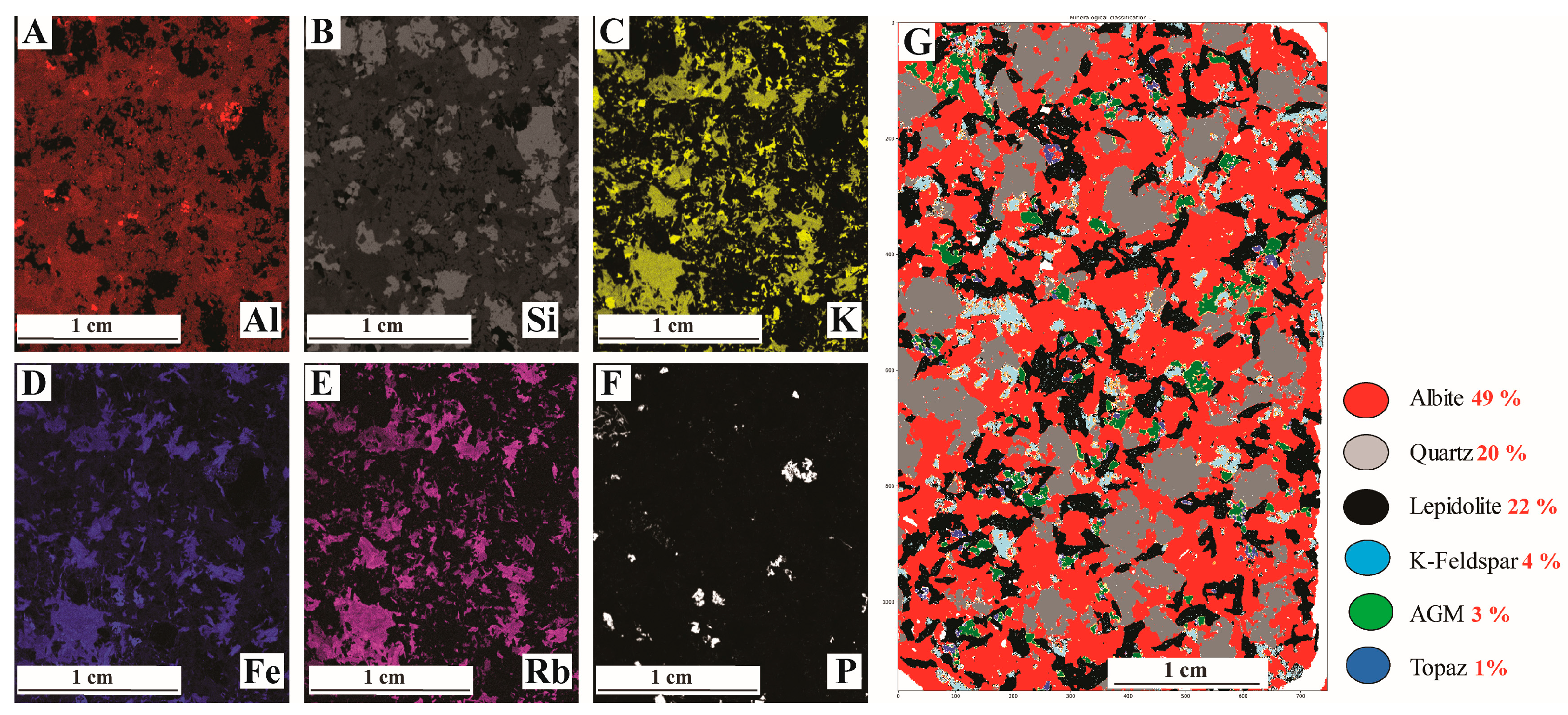

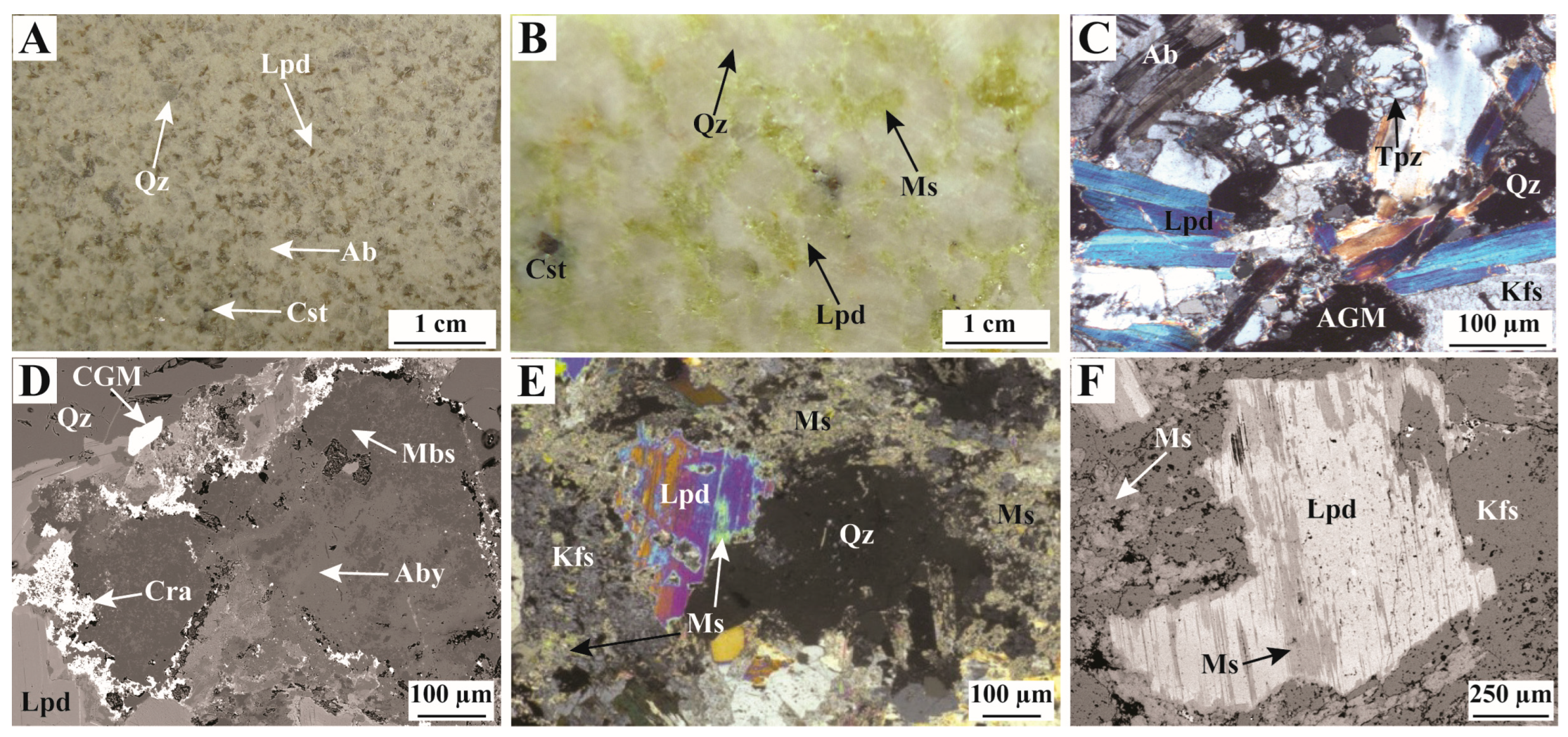

3.1. Textural Characterization of the Beauvoir Granite

3.2. Micro-XRF Modal Abundances

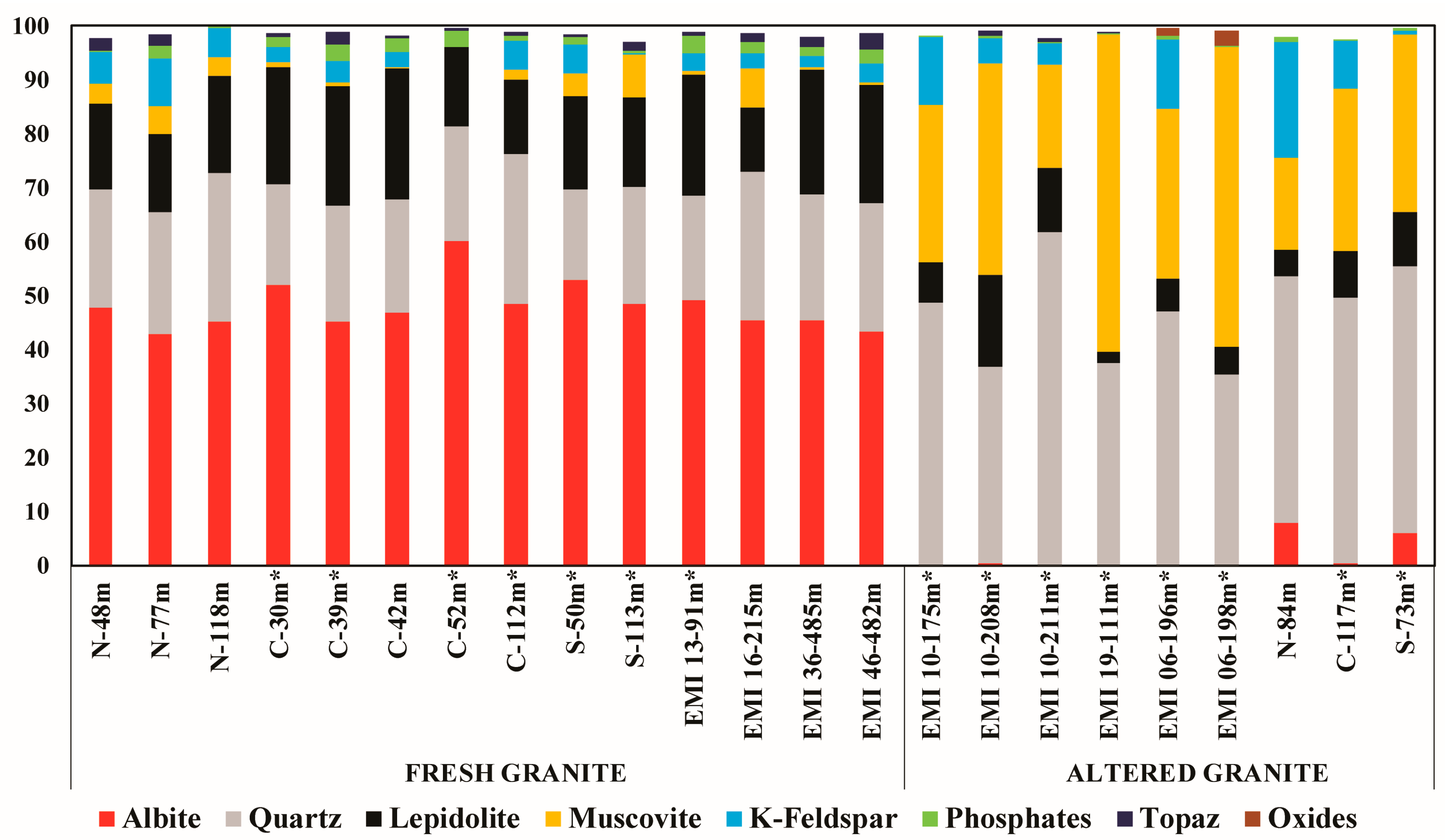

3.2.1. Fresh Granite

3.2.2. Altered Facies

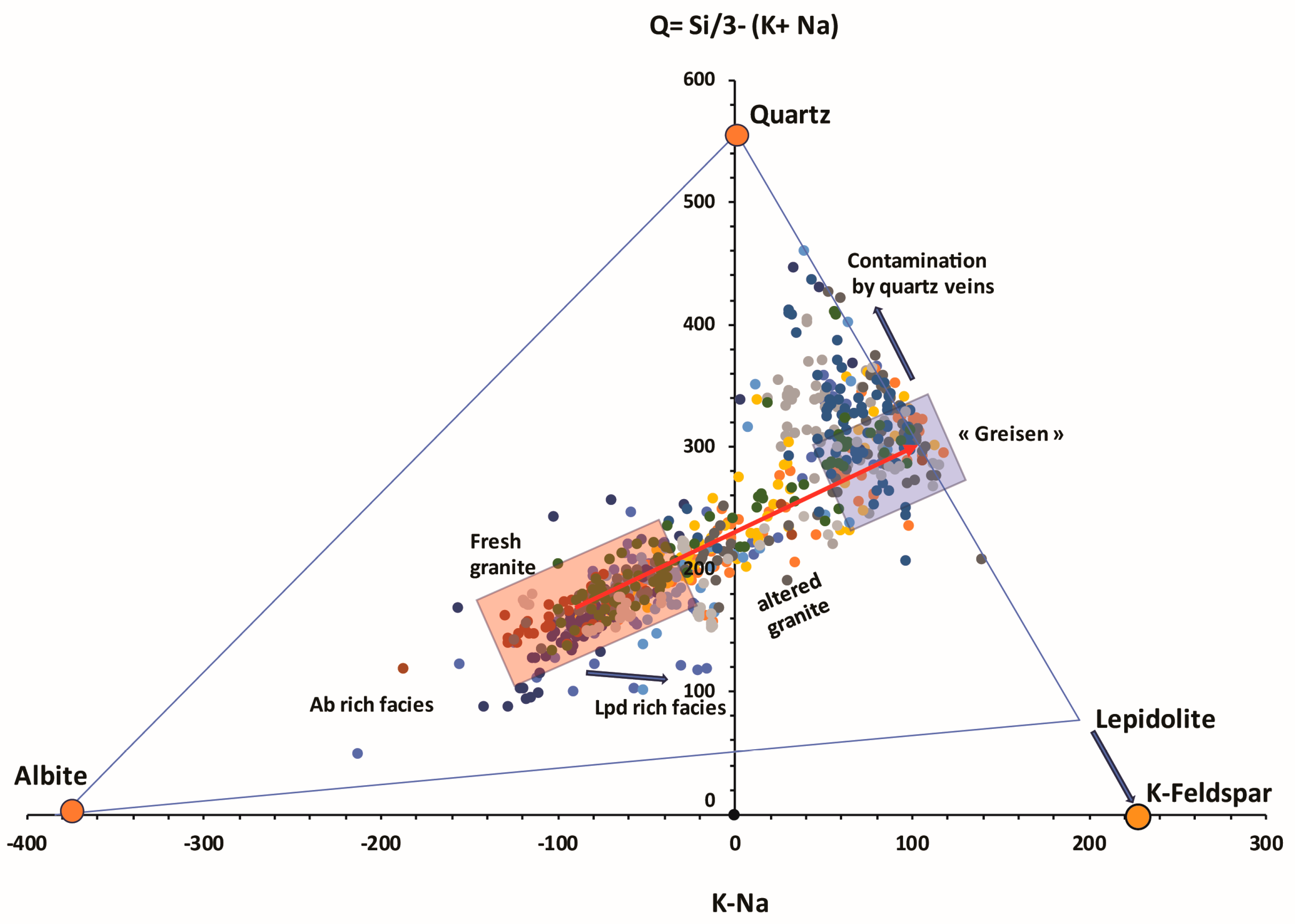

3.3. Normative Proportions Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages and Limitations of the Different Quantitative Mineralogical Methods and Comparison to LIBS

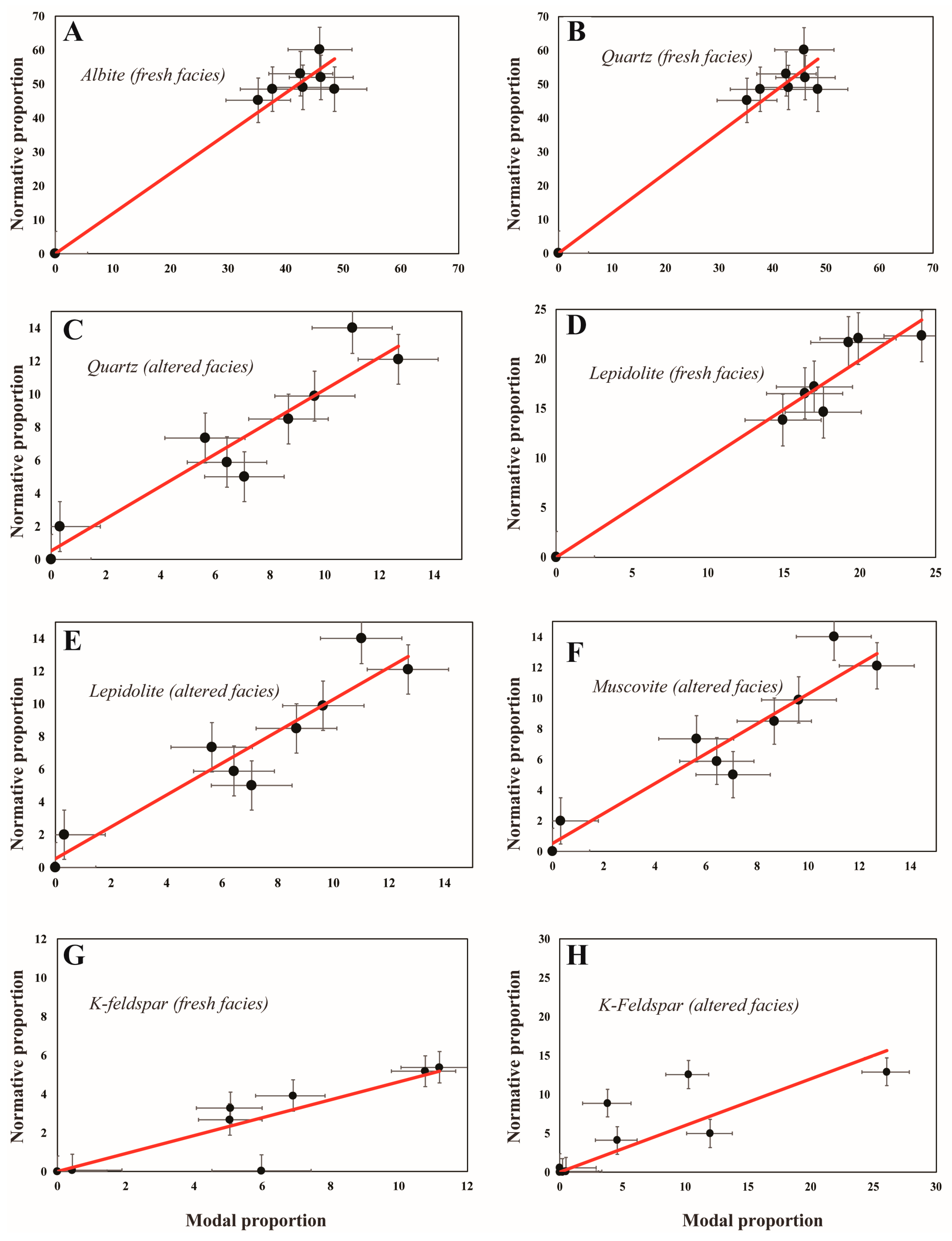

4.2. Modal and Normative Quantitative Mineralogy Comparison

4.3. Implications for Facies Classification of Beauvoir Granite and Lithium Recovery

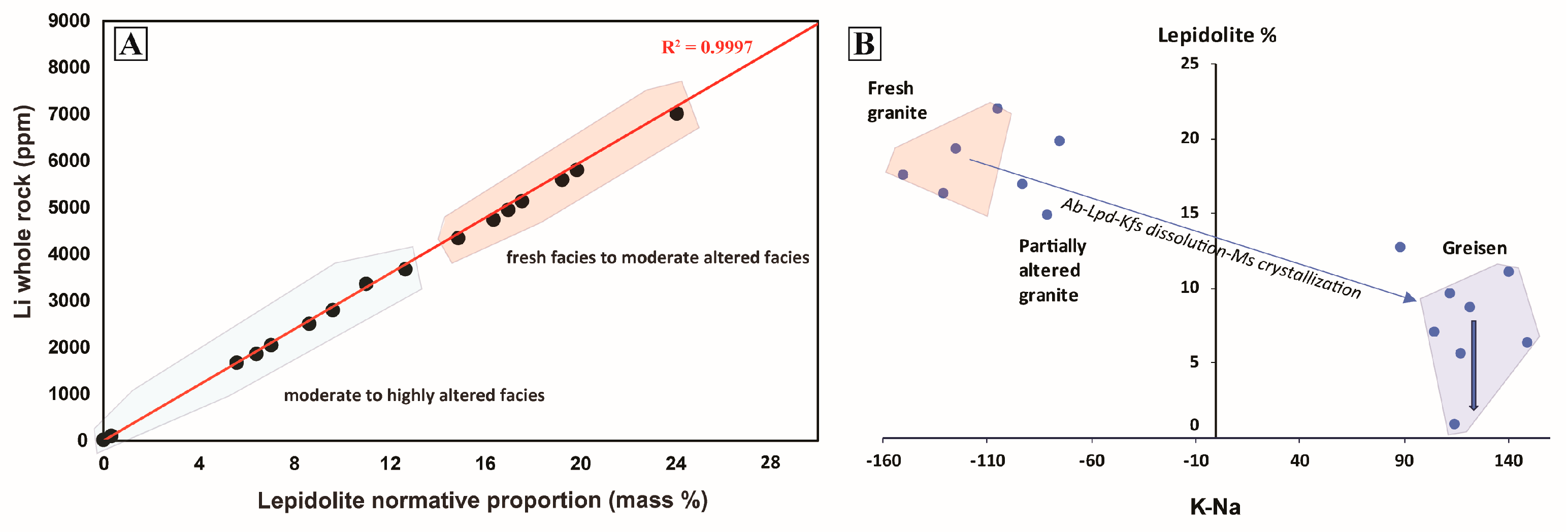

4.4. Quantitative Estimation of Lepidolite: Comparison and Integration of Bulk-Rock Geochemistry and Chemical Mapping

5. Conclusions

- Elemental and chemical composite mapping combined with modal mineralogy highlights the usefulness of micro-XRF for mineralogical characterization.

- Beyond qualitative mapping, Micro-XRF imaging enables quantitative comparisons with normative and modal mineralogy, providing insights into the respective strengths and limitations of each approach.

- Micro-XRF results, in conjunction with normative mineral proportion calculations, reveal similar mineralogical abundances for fresh granite; however, noticeable discrepancies occur in the estimation of muscovite in the altered facies.

- By comparing mineralogical proportions with Li content, this study allows the discrimination of fresh and altered facies based on their mineral signatures, thereby improving deposit characterization and predictions of ore-processing performance.

- Micro-XRF is not suitable for the direct quantification of lithium-bearing minerals as it cannot detect elements with atomic numbers below sodium (Z = 11). This intrinsic limitation highlights the necessity of complementary analytical techniques, such as ICP-MS or LA-ICP-MS, when investigating lithium-rich phases.

- Overall, this work demonstrates the value of quantitative mineralogy—particularly for Li-bearing rare-metal granites—in providing critical information on the abundance of Li-bearing minerals and the potential presence of Li-poor muscovite acting as a diluting component in flotation mica concentrates.

- In Li-mica–bearing peraluminous granites such as Beauvoir, neither normative nor modal approaches alone provide a fully reliable estimate of lepidolite abundance. Whole-rock geochemistry ensures volumetric representativeness at the drill-core scale but suffers from under-determined systems where several K-bearing phases coexist. Conversely, micro-XRF mapping allows precise discrimination of mineral phases and alteration textures but is limited by surface representativeness. Their combined use enables cross-calibration of mineral proportions, reduces methodological uncertainties, and provides a robust framework for resource estimation and orebody modeling.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harlaux, M.; Mercadier, J.; Bonzi, W.M.-E.; Kremer, V.; Marignac, C.; Cuney, M. Geochemical Signature of Magmatic-Hydrothermal Fluids Exsolved from the Beauvoir Rare-Metal Granite (Massif Central, France): Insights from LA-ICPMS Analysis of Primary Fluid Inclusions. Geofluids 2017, 2017, 1925817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathelineau, M.; Kahou, Z.S. Discrimination of Muscovitisation Processes Using a Modified Quartz–Feldspar Diagram: Application to Beauvoir Greisens. Minerals 2024, 14, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, L.N. IMA–CNMNC Approved Mineral Symbols. Mineral. Mag. 2021, 85, 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Rifai, K.; Selmani, S.; Constantin, M.; Doucet, F.R.; Özcan, L.Ç.; Sabsabi, M.; Vidal, F. Chemical and Mineralogical Mapping of Platinum-Group Element Ore Samples Using Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy and Micro-X-Ray Fluorescence. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2021, 45, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Jean, C. Hameye/MARCIA: MARCIA v 0.1.3. Zenodo 2021, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.; Iddings, J.P.; Pirsson, L.V.; Washington, H.S. A Quantitative Chemico-Mineralogical Classification and Nomenclature of Igneous Rocks. J. Geol. 1902, 10, 555–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, R. The Use of Linear Programming in the Analysis of Petrological Mixing Problems. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1979, 70, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosana-Delgado, R.; von Eynatten, H.; Karius, V. Constructing Modal Mineralogy from Geochemical Composition: A Geometric-Bayesian Approach. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltje, G.J. End-Member Modeling of Compositional Data: Numerical-Statistical Algorithms for Solving the Explicit Mixing Problem. Math. Geol. 1997, 29, 503–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, G.E. Quantitative Analysis of Mineral Mixtures Using Linear Programming. Clays Clay Miner. 1986, 34, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuney, M.; Marignac, C.; Weisbrod, A. The Beauvoir Topaz-Lepidolite Albite Granite (Massif Central, France); the Disseminated Magmatic Sn-Li-Ta-Nb-Be Mineralization. Econ. Geol. 1992, 87, 1766–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, G.; Burnol, L. Observations Sur Les Mineralisations En Beryllium Du Massif Granitique d’Echassiers Decouverte de Herderite. Acad. Sience Comptes Rendus 1964, 258, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Burnol, L. Geochimie du Beryllium et Types de Concentration dans les Leucogranites du Massif Central Francais; Relations Entre les Caracteristiques Geochimiques des Granitoides et les Gisements Endogenes de Type Depart Acide (Be, Sn, Li) ou de Remaniement Tardif (U, F, Pb et Zn); BRGM: Orléans, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Charoy, B. Beryllium Speciation in Evolved Granitic Magmas; Phosphates versus Silicates. Eur. J. Mineral. 1999, 11, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Demeusy, B.; Arias-Quintero, C.A.; Butin, G.; Lainé, J.; Tripathy, S.K.; Marin, J.; Dehaine, Q.; Filippov, L.O. Characterization and Liberation Study of the Beauvoir Granite for Lithium Mica Recovery. Minerals 2023, 13, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.R.; Fontan, F.; Monchoux, P. Interrelations et Évolution Comparée de La Cassitérite et Des Niobotantales Dans Les Différents Faciès Du Granite de Beauvoir (Massif d’Echassières). Géologie Fr. 1987, 2–3, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.C. Minéraux Disséminés Comme Indicateurs du Caractère Pegmatitique du Granite de Beauvoir, Massif d’Echassières, Allier, France. Can. Mineral. 1992, 30, 763–770. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetapple, M.T.; Tassios, S. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) as a Tool for In Situ Mapping and Textural Interpretation of Lithium in Pegmatite Minerals. Am. Mineral. 2015, 100, 2141–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifai, K.; Constantin, M.; Yilmaz, A.; Özcan, L.Ç.; Doucet, F.R.; Azami, N. Quantification of Lithium and Mineralogical Mapping in Crushed Ore Samples Using Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Minerals 2022, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, C.; Trebus, K.; Tarantola, A.; Cauzid, J.; Motto-Ros, V.; Voudouris, P. Advances on microLIBS and microXRF Mineralogical and Elemental Quantitative Imaging. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2022, 194, 106470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballouard, C.; Carr, P.; Parisot, F.; Gloaguen, É.; Melleton, J.; Cauzid, J.; Lecomte, A.; Rouer, O.; Salsi, L.; Mercadier, J. Petrogenesis and Tectonic-Magmatic Context of Emplacement of Lepidolite and Petalite Pegmatites from the Fregeneda-Almendra Field (Variscan Central Iberian Zone): Clues from Nb-Ta-Sn Oxide U-Pb Geochronology and Mineral Geochemistry. BSGF–Earth Sci. Bul. 2024, 195, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, J.A.-S.; Gumiaux, C.; Pichavant, M.; Gloaguen, E.; Marcoux, E. From Magmatic to Hydrothermal Sn-Li-(Nb-Ta-W) Mineralization: The Argemela Area (Central Portugal). Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 116, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimbault, L.; Cuney, M.; Azencott, C.; Duthou, J.-L.; Joron, J.L. Geochemical Evidence for a Multistage Magmatic Genesis of Ta-Sn-Li Mineralization in the Granite at Beauvoir, French Massif Central. Econ. Geol. 1995, 90, 548–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiter, K.; Hložková, M.; Korbelová, Z.; Galiová, M.V. Diversity of Lithium Mica Compositions in Mineralized Granite–Greisen System: Cínovec Li-Sn-W Deposit, Erzgebirge. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 106, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlaux, M.; Blein, O.; Gourcerol, B. Comparison of the Beauvoir and Cínovec Rare Metal Granite/Greisen Systems: Role of Muscovitization on Li-Sn-W-Ta Hydrothermal Remobilization. In Proceedings of the 17th Biennial SGA Meeting, Zurich, Switzerland, 28 August–1 September 2023; pp. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kahou, S.; Cathelineau, M.; Boiron, M.-C. Quantitative Mineralogy and Lithium Distribution in the Upper Part of the Beauvoir Granite; European Geosciences Union General Assembly: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Monnier, L.; Salvi, S.; Melleton, J.; Lach, P.; Pochon, A.; Bailly, L.; Béziat, D.; De Parseval, P. Mica Trace-Element Signatures: Highlighting Superimposed W-Sn Mineralizations and Fluid Sources. Chem. Geol. 2022, 600, 120866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drill Hole. | Sample Number | Depth (m) | Mineralogy | Facies Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PER North | N48 | 48 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh |

| N77 | 77 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh | |

| N84 | 84 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Ap | altered | |

| N118 | 118 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, Ms, AGM, Tpz | fresh | |

| PER Center | C30 | 30 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh |

| C39 | 39 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh | |

| C42 | 42 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh | |

| C52 | 52 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh | |

| C112 | 112 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh | |

| C117 | 117 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Kfs | altered | |

| PER South | S50 | 50 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz, Ms | fresh |

| S73 | 73 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Kfs | altered | |

| S113 | 113 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz, Ms | fresh | |

| EMI 006 | EMI6-196 | 196 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, CGM, Ap | altered |

| EMI6-198 | 198 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Cst | altered | |

| EMI 010 | EMI10-175 | 175 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Kfs | altered |

| EMI10-208 | 208 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, Ap | altered | |

| EMI10-211 | 211 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Kfs | altered | |

| EMI 013 | EMI13-91 | 91 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz | fresh |

| EMI 016 | EMI16-215 | 215 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, Ms, AGM, Tpz | fresh |

| EMI 019 | EMI19-111 | 111 | Ms, Qz, Lpd, Ap | altered |

| EMI 036 | EMI36-485 | 485 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz, Ms | fresh |

| EMI 046 | EMI46-482 | 482 | Ab, Qz, Lpd, Kfs, AGM, Tpz, Ms | fresh |

| Mineral | SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | P2O5 | Li2O | F | Rb2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albite | 68.2 | 0 | 19.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quartz | 99.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepidolite | 51.8 | 0 | 22.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 9.9 | 0 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 2.2 |

| Microcline | 64.8 | 0 | 18.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 16.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 |

| Muscovite | 46.0 | 0 | 36.4 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 10.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Topaz | 32.6 | 0 | 56.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17.5 | 0 |

| Amblygonite | 0 | 0 | 36.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 7.5 | 0 | 46.9 | 6.0 | 8.8 | 0 |

| Apatite | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 55.2 | 0 | 0 | 41.8 | 0 | 3.9 | 0 |

| Fresh Granite | ||||||||

| Sample/Mineral | Albite | Quartz | Lepidolite | Muscovite | K-Feldspar | AGM | Topaz | Oxides |

| N-48m | 48 | 22 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| N-77m | 43 | 23 | 14 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| N-118m | 45 | 28 | 18 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C-30m | 52 | 19 | 22 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| C-39m | 45 | 21 | 22 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| C-42m | 47 | 21 | 24 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| C-52m | 60 | 21 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| C-112m | 49 | 28 | 14 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| S-50m | 53 | 17 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| S-113m | 49 | 22 | 17 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| EMI 13-91m | 49 | 19 | 22 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| EMI 16-215m | 45 | 28 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| EMI 36-485m | 46 | 23 | 23 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| EMI 46-482m | 43 | 24 | 22 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Altered Granite | ||||||||

| Sample/Mineral | Albite | Quartz | Lepidolite | Muscovite | K-Feldspar | Apatite | Topaz | Oxides |

| EMI 10-175m | 0 | 49 | 7 | 29 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EMI 10-208m | 0 | 37 | 14 | 41 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| EMI 10-211m | 0 | 62 | 12 | 19 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| EMI 19-111m | 0 | 38 | 2 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EMI 06-196m | 0 | 47 | 6 | 32 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| EMI 06-198m | 0 | 36 | 5 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| N-84m | 8 | 46 | 5 | 17 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C-117m | 1 | 49 | 9 | 30 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S-73m | 6 | 50 | 10 | 33 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

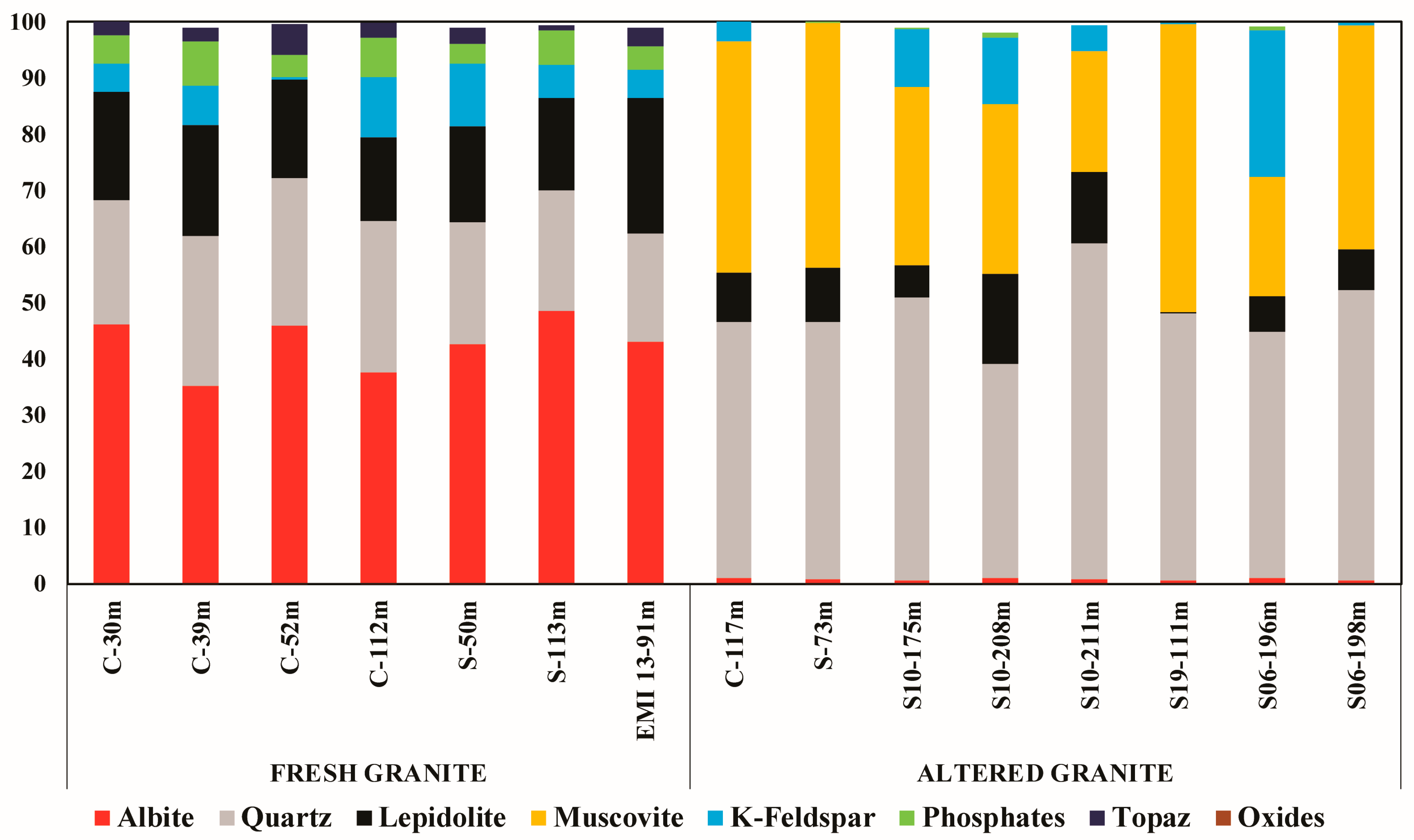

| FRESH GRANITE | ||||||||||||||||

| Mineral/Sample | C-30m | C-39m | C-52m | C-112m | S-50m | S-113m | EMI 13-91m | |||||||||

| Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | |||

| Albite | 46 | 52 | 35 | 45 | 46 | 60 | 38 | 49 | 43 | 53 | 49 | 49 | 43 | 49 | ||

| Quartz | 22 | 19 | 27 | 21 | 26 | 21 | 27 | 28 | 22 | 17 | 22 | 22 | 19 | 19 | ||

| Lepidolite | 19 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 24 | 22 | ||

| Muscovite | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 | ||

| K-Feldspar | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 3 | ||

| AGM | 5 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Topaz | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Oxides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ALTERED GRANITE | ||||||||||||||||

| Mineral/Sample | C-117m | S-73m | EMI 10-175m | EMI 10-208m | EMI 10-211m | EMI 19-111m | EMI 06-196m | EMI 06-198m | ||||||||

| Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | Normative | Modal | |

| Albite | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Quartz | 46 | 49 | 46 | 50 | 50 | 49 | 40 | 37 | 60 | 62 | 47 | 38 | 44 | 47 | 52 | 36 |

| Lepidolite | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| Muscovite | 41 | 30 | 44 | 33 | 32 | 29 | 33 | 41 | 22 | 19 | 51 | 59 | 21 | 32 | 40 | 56 |

| K-Feldspar | 4 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 13 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Apatite | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Topaz | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oxides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Sample | Li Whole-Rock Content (ppm) | Lepidolite Normative Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| C30 | 5591 | 19 |

| C39 | 5788 | 20 |

| C52 | 5121 | 18 |

| C112 | 4329 | 15 |

| S50 | 4927 | 17 |

| S113 | 4726 | 16 |

| EMI13-91 | 6997 | 24 |

| C117 | 2500 | 9 |

| S73 | 2781 | 10 |

| EMI10-175 | 1651 | 6 |

| EMI10-208 | 3352 | 11 |

| EMI10-211 | 3653 | 13 |

| EMI19-111 | 97 | 1 |

| EMI6-196 | 1851 | 6 |

| EMI6-198 | 2026 | 7 |

| Aspect | Normative Approach (Whole-Rock Geochemistry) | Modal Approach (Micro-XRF Mapping) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Mineral proportions calculated from bulk-rock chemistry using mass balance. | Direct identification and surface quantification of mineral phases from elemental maps. |

| Scale | Decimetric to metric (e.g., 4 m drill-core intervals). | Millimetric to centimetric (thin/thick sections). |

| Representativeness | High, provided sampling and quartering are robust. | Limited; depends on number of sections and textural homogeneity. |

| Discrimination of K-bearing phases | Limited when several phases share major elements (under-determined systems). | High, using phase-specific chemical thresholds (MARCIA approach). |

| Sensitivity to Li | High at bulk scale, indirect at mineral scale. | Indirect (Li not detected), inferred from associated elements and calibration. |

| Sensitivity to alteration | Expressed as bulk metal loss | Explicitly resolved through replacement textures (e.g., lepidolite → muscovite). |

| Main uncertainties | Assumed mineral compositions; phase overlap. | Surface-to-volume extrapolation. |

| Strengths | Robust drill-core–scale estimates. | High mineralogical and textural resolution. |

| Limitations | Poor resolution of textural controls. | Cannot be extrapolated alone to resource scale. |

| Optimal combined use | Provides volumetric control and resource-scale continuity. | Provides calibration, phase discrimination and correction factors. |

| Implications for exploration and resource modeling | Ensures reliable grade and tonnage estimation at borehole scale | Improves mineralogical accuracy and correction of normative models in heterogeneous or altered facies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kahou, Z.S.; Cathelineau, M.; Bonzi, W.M.-E.; Salsi, L.; Fullenwarth, P. Micro-XRF-Based Quantitative Mineralogy of the Beauvoir Li Granite: A Tool for Facies Characterization and Ore Processing Optimization. Minerals 2026, 16, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010029

Kahou ZS, Cathelineau M, Bonzi WM-E, Salsi L, Fullenwarth P. Micro-XRF-Based Quantitative Mineralogy of the Beauvoir Li Granite: A Tool for Facies Characterization and Ore Processing Optimization. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleKahou, Zia Steven, Michel Cathelineau, Wilédio Marc-Emile Bonzi, Lise Salsi, and Patrick Fullenwarth. 2026. "Micro-XRF-Based Quantitative Mineralogy of the Beauvoir Li Granite: A Tool for Facies Characterization and Ore Processing Optimization" Minerals 16, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010029

APA StyleKahou, Z. S., Cathelineau, M., Bonzi, W. M.-E., Salsi, L., & Fullenwarth, P. (2026). Micro-XRF-Based Quantitative Mineralogy of the Beauvoir Li Granite: A Tool for Facies Characterization and Ore Processing Optimization. Minerals, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010029