Kinematics and Dynamics Behaviour of Milling Media in Vertical Spiral Stirred Mill Based on DEM-CFD Coupling

Abstract

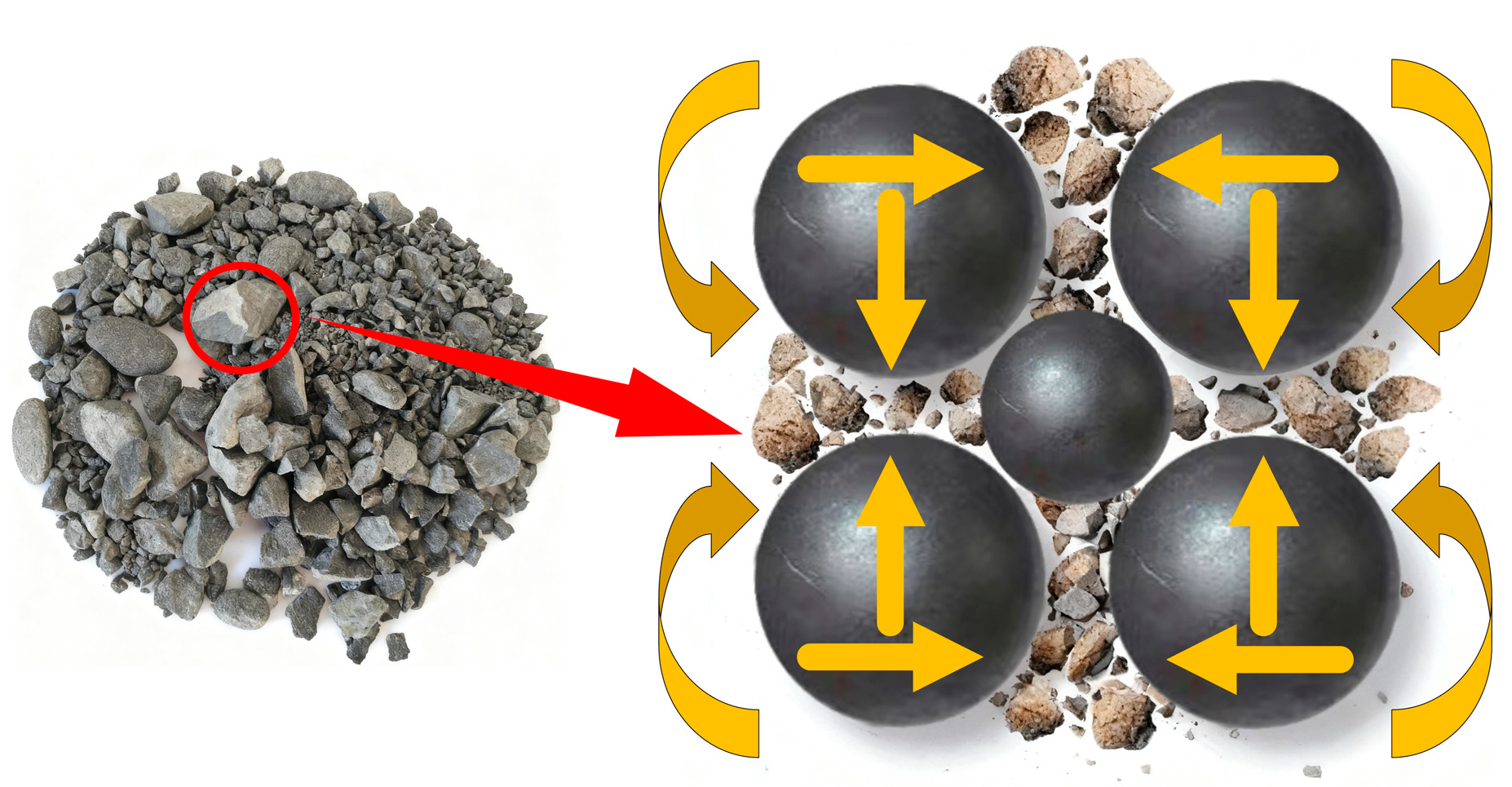

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Contact Model

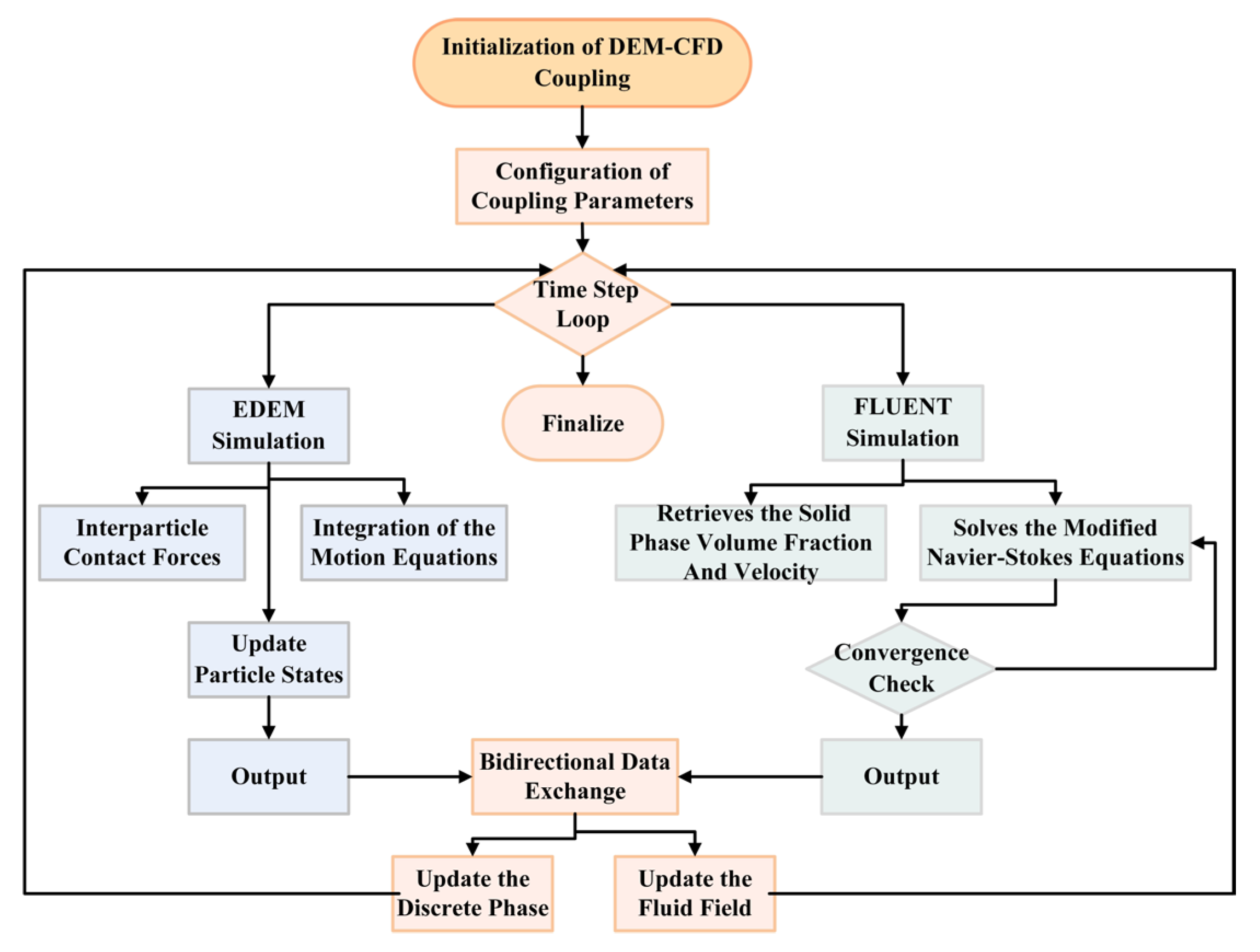

2.2. DEM-CFD Coupling Model

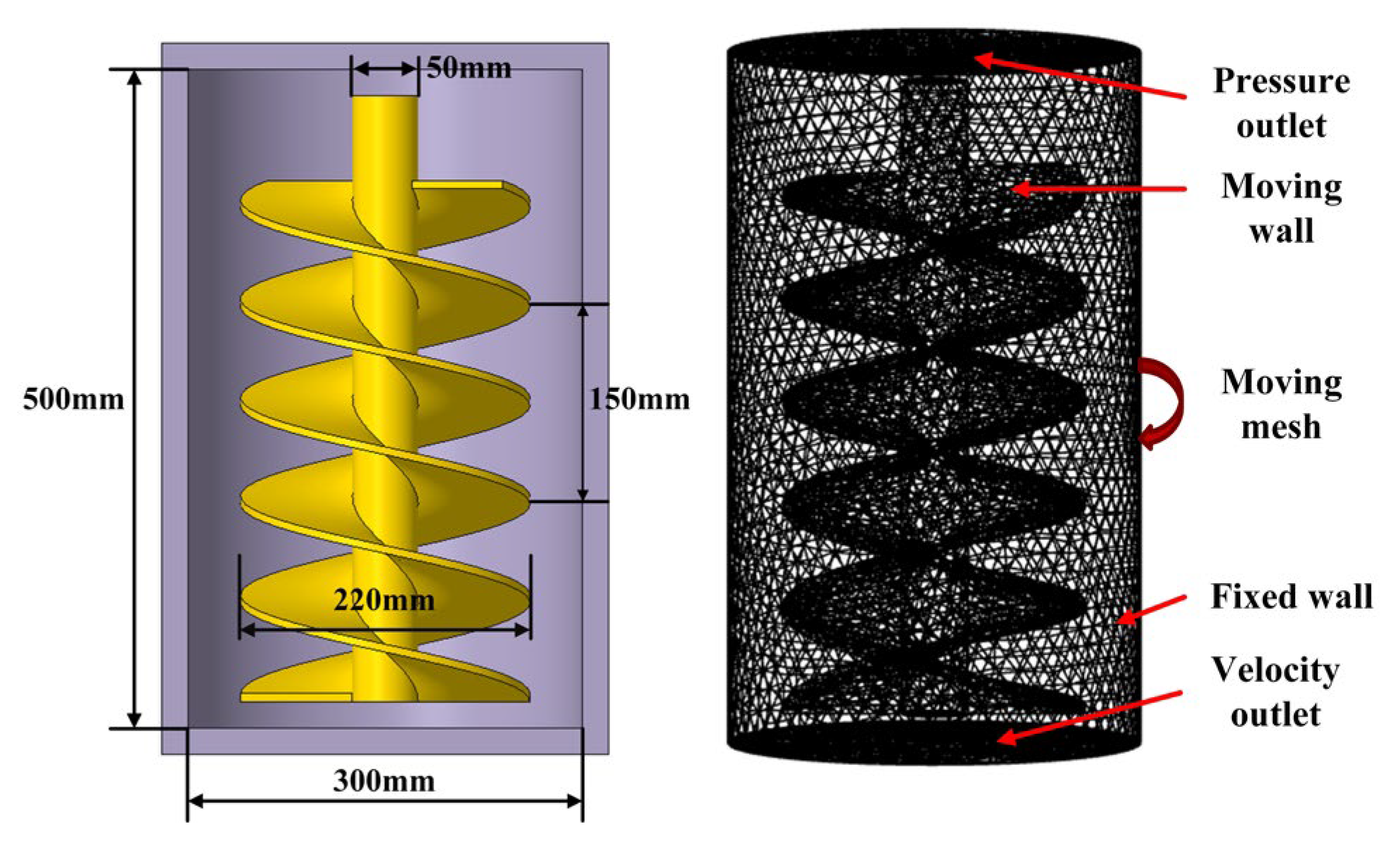

2.3. Simulation Model

2.4. Experimental Verification

2.5. Design of Simulation Experiments

3. Results and Analyses

3.1. Effect of Rotational Speed on Media Kinematics and Dynamics

3.2. Effect of Diameter on Media Kinematics and Dynamics

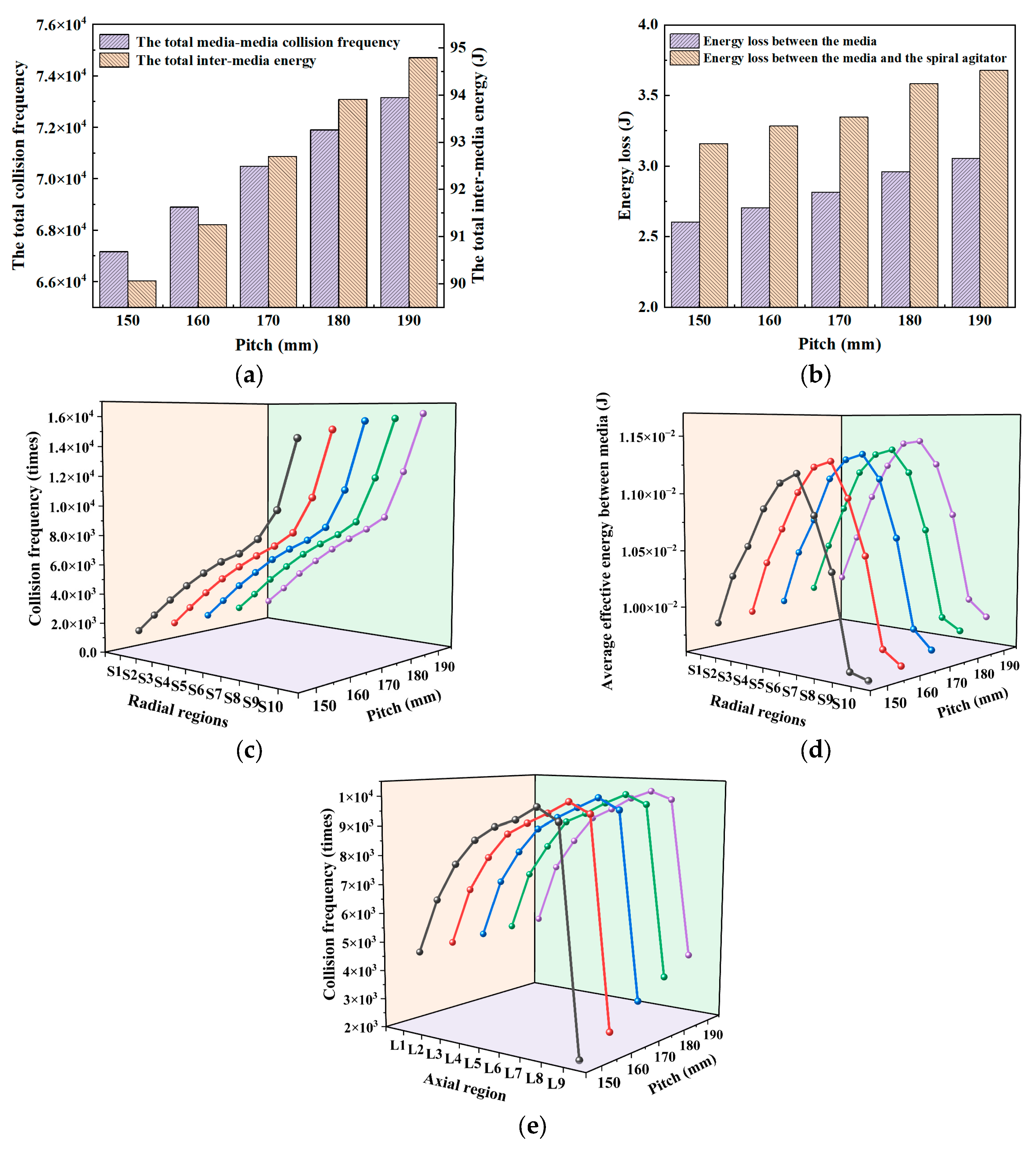

3.3. Effect of Pitch on Media Kinematics and Dynamics

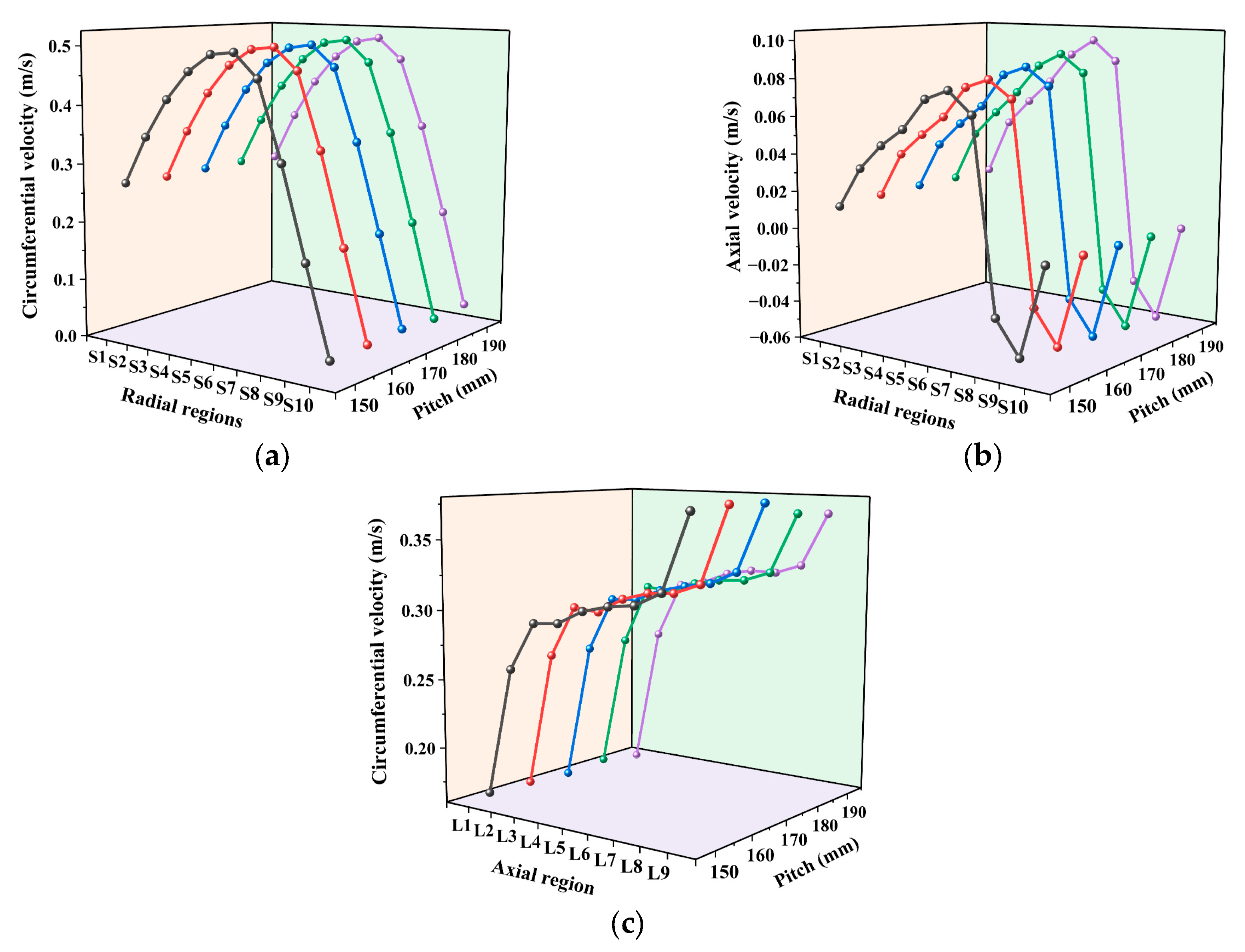

3.4. Effect of Filling Level on Media Kinematics and Dynamics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Carvalho, R.M.; Oliveira, A.L.R.; Petit, H.A.; Tavares, L.M. Comparing Modeling Approaches in Simulating a Continuous Pilot-Scale Wet Vertical Stirred Mill Using PBM-DEM-CFD. Adv. Powder Technol. 2023, 34, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, Z.; Liao, N.; Zeng, C.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J. Enhancing the Grinding Efficiency of a Magnetite Second-Stage Mill through Ceramic Ball Optimization: From Laboratory to Industrial Applications. Minerals 2024, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Morrison, R.; Cervellin, A.; Burns, F.; Musa, F. Comparison of Energy Efficiency between Ball Mills and Stirred Mills in Coarse Grinding. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, G.; Feng, Q.; Xiao, S.; Huang, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z. The Liberation Effect of Magnetite Fine Ground by Vertical Stirred Mill and Ball Mill. Miner. Eng. 2012, 34, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Li, X.H.; Gao, H.D.; Zhang, L.X.; You, F. Design and Analysis of a Vertical Screw Stirring Device for Feeding Dairy Goats. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2023, 22, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, P.M.; Mazzinghy, D.B.; Galéry, R.; Machado, L.C.R. Industrial Vertical Stirred Mills Screw Liner Wear Profile Compared to Discrete Element Method Simulations. Minerals 2021, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfels, C.; Dambach, R.; Kwade, A. Geometry Influence on Optimized Operation of a Dry Agitator Bead Mill. Miner. Eng. 2021, 171, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, U.; Vivacqua, V.; Calvert, G.; Ghadiri, M.; Cleaver, J.A.S. A Review of Bulk Powder Caking. Powder Technol. 2017, 313, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, M.; Altun, O. Performance Comparison of the Vertical and Horizontal Oriented Stirred Mill: Pilot Scale IsaMill vs. Full-Scale HIGMill. Minerals 2023, 13, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Curtis, J.S. Discrete Element Method Simulations for Complex Granular Flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2015, 47, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, W.S. Analysis of Ball Movement for Research of Grinding Mechanism of a Stirred Ball Mill with 3D Discrete Element Method. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 25, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Lv, W. Effect of Lifters and Mill Speed on Particle Behaviour, Torque, and Power Consumption of a Tumbling Ball Mill: Experimental Study and DEM Simulation. Miner. Eng. 2017, 105, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, S.; Tsunazawa, Y.; Hisatomi, S.; Granata, G.; Tokoro, C.; Okuyama, K.; Iwamoto, M.; Sekine, Y. Effect of Agitator Shaft Direction on Grinding Performance in Media Stirred Mill: Investigation Using DEM Simulation. Mater. Trans. 2018, 59, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.; Rhymer, D.; Werner, D.; Ingram, A.; Windows-Yule, C.R.K. Investigating the Impact of Impeller Geometry for a Stirred Mill Using the Discrete Element Method: Effect of Pin Number and Thickness. Powder Technol. 2023, 428, 118810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraio, D.; Villoria, J.; Ingram, A.; Alexiadis, A.; Stitt, E.H.; Marigo, M. Investigating Grinding Media Dynamics inside a Vertical Stirred Mill Using the Discrete Element Method: Effect of Impeller Arm Length. Powder Technol. 2020, 364, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhymer, D.; Ingram, A.; Sadler, K.; Windows-Yule, C.R.K. A Discrete Element Method Investigation within Vertical Stirred Milling: Changing the Grinding Media Restitution and Sliding Friction Coefficients. Powder Technol. 2022, 410, 117825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhymer, D.; Ingram, A.; Sadler, K.; Windows-Yule, C.R.K. Segregation in Binary and Polydisperse Stirred Media Mills and Its Role on Grinding Effectiveness. Powder Technol. 2024, 443, 119921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, R.; Li, D.; Zeng, Q.; Wen, X.; Lv, J.; Yan, X.; Ran, J.; Zhang, H. Flow Field Analysis and Engineering Application of the Turbulence-Forced Pulp Conditioner. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2025, 61, 210645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.; Chen, M.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Y. A Review of Recent Development for the CFD-DEM Investigations of Non-Spherical Particles. Powder Technol. 2022, 412, 117972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Zheng, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, B.; Ji, H.; Zhao, Z. Multi Factor Analysis of the Vertical Roller Mill Separator Based on BP Neural Network—Response Surface Joint Modeling. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2025, 61, 208769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragnière, G.; Naumann, A.; Schrader, M.; Kwade, A.; Schilde, C. Grinding Media Motion and Collisions in Different Zones of Stirred Media Mills. Minerals 2021, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Wang, Z.; Qu, T.; Song, X.; Tang, B.; Li, Y.; Ma, L. Grinding Mechanism of Wet Vertical Spiral Stirred Mill Based on DEM-CFD: Role of Grinding Sphere Motion. Particuology 2025, 103, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.; Naude, N. Investigating the Effect on Power Draw and Grinding Performance When Adding a Shell Liner to a Vertical Fluidised Stirred Media Mill. Miner. Eng. 2021, 160, 106698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.; Rodríguez Prieto, J.M.; Heiskari, H.; Jonsén, P. A Novel Particle-Based Approach for Modeling a Wet Vertical Stirred Media Mill. Minerals 2021, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winardi, S.; Widiyastuti, W.; Septiani, E.L.; Nurtono, T. Simulation of Solid-Liquid Flows in a Stirred Bead Mill Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 054002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsén, P.; Hammarberg, S.; Pålsson, B.I.; Lindkvist, G. Preliminary Validation of a New Way to Model Physical Interactions between Pulp, Charge and Mill Structure in Tumbling Mills. Miner. Eng. 2019, 130, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Herrera, N.; Barrios, G.K.P.; Tavares, L.M. Comparison of Breakage Models in DEM in Simulating Impact on Particle Beds. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragnière, G.; Beinert, S.; Overbeck, A.; Kampen, I.; Schilde, C.; Kwade, A. Predicting Effects of Operating Condition Variations on Breakage Rates in Stirred Media Mills. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 138, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.R.; Rodriguez, V.A.; De Carvalho, R.M.; Powell, M.S.; Tavares, L.M. Mechanistic Modeling and Simulation of a Batch Vertical Stirred Mill. Miner. Eng. 2020, 156, 106487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H. CFD-DEM Modeling of Particle Dissolution Behavior in Stirred Tanks. Powder Technol. 2024, 442, 119894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, D. Investigation of the Force Closure for Eulerian-Eulerian Simulations: A Validation Study of Nine Gas-Liquid Flow Cases. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.01189. [Google Scholar]

- Piredda, M.M.; Asinari, P. Lattice Boltzmann Framework for Multiphase Flows by Eulerian–Eulerian Navier–Stokes Equations. Computation 2025, 13, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, H.A.; De Oliveira, A.L.R.; Tavares, L.M. Validation of a Rheology-Dependent PBM-DEM-CFD Simulation Model of a Continuous Vertical Stirred Mill Operating under Different Conditions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 306, 121260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhonsale, S.; Scott, L.; Ghadiri, M.; Van Impe, J. Numerical Simulation of Particle Dynamics in a Spiral Jet Mill via Coupled CFD-DEM. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, R.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, S.; Xing, H.; Chen, L.; Yang, F. Mechanical Characteristics of Roll Crushing of Ore Materials Based on Discrete Element Method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Huang, J.; Guo, J.; Mo, Y. Study on Wear Properties of the Flow Parts in a Centrifugal Pump Based on EDEM–Fluent Coupling. Processes 2019, 7, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhao, L.; Mo, X.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Y. Coupled CFD-DEM Numerical Simulation of the Interaction of a Flow-Transported Rag with a Solid Cylinder. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2024, 20, 1593–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Durbin, P.A.; Medic, G. Development of an Elliptic Blending Lag k − ω Model. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2019, 76, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, T.; Ma, L.; Song, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, H. Coupling simulation methodand experiment of vertical stirring mill based on DEM–CFD. Conserv. Util. Miner. Resour. 2025, 45, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, B.; Cheng, B.; Song, X.; Ji, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Experimental Study on the Influence of Rotational Speed on Grinding Efficiency for the Vertical Stirred Mill. Minerals 2024, 14, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. DEM Simulation and Analysis of Operating Parameters on Grinding Performance of a Vertical Stirred Media Mill. Master’s Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasundara, C.T.; Yang, R.Y.; Yu, A.B.; Curry, D. Discrete Particle Simulation of Particle Flow in IsaMill—Effect of Grinding Medium Properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 135, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Mao, Y.; Ding, H.; Wu, S.; Xie, P.; Huang, Q. Analysis of Grinding Media Motion Behavior in a Vertical Spiral Stirred Mill Based on Discrete Element Method. Granul. Matter 2025, 27, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Setting | Parameters | Values | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEM settings | Individual parameters | Ball | Mill |

| Density | 7800 kg/m3 | 7800 kg/m3 | |

| Shear stiffness | 7 × 1010 pa | 7 × 1010 pa | |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Contact parameters | Ball-ball | Ball-mill | |

| Coefficient of restitution | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Coefficient of static friction | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Coefficient of rolling friction | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Composition | TFe | FeO | SiO2 | MgO | Al2O3 | CaO | P | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | 33.42 | 4.81 | 46.92 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 0.043 | 0.026 |

| Parameters | Spiral Agitator Rotational Speed (rpm) | Media Filling Mass (kg) | Grinding Media Diameter (mm) | Stirring Spiral Angle (°) | Slurry Solid Concentration (%) | Slurry Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 175 | 49 | 8 | 14.21 | 62.5 | 1957.4 |

| Simulation Results | 15.66 | 15.69 | 15.71 |

| Error | 3.4% | 3.27% | 3.14% |

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiral agitator rotational speed (rpm) | 80 | 90 | 100 | 110 | 120 |

| Spiral agitator diameter (mm) | 200 | 205 | 210 | 215 | 220 |

| Spiral agitator pitch (mm) | 150 | 160 | 170 | 180 | 190 |

| Media filling level (%) | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gu, R.; Wu, W.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Qin, Z.; Wang, Y. Kinematics and Dynamics Behaviour of Milling Media in Vertical Spiral Stirred Mill Based on DEM-CFD Coupling. Minerals 2026, 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010024

Gu R, Wu W, Zhao S, Ma Z, Wang Q, Qin Z, Wang Y. Kinematics and Dynamics Behaviour of Milling Media in Vertical Spiral Stirred Mill Based on DEM-CFD Coupling. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Ruijie, Wenzhe Wu, Shuaifeng Zhao, Zhenyu Ma, Qiang Wang, Zhenzhong Qin, and Yan Wang. 2026. "Kinematics and Dynamics Behaviour of Milling Media in Vertical Spiral Stirred Mill Based on DEM-CFD Coupling" Minerals 16, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010024

APA StyleGu, R., Wu, W., Zhao, S., Ma, Z., Wang, Q., Qin, Z., & Wang, Y. (2026). Kinematics and Dynamics Behaviour of Milling Media in Vertical Spiral Stirred Mill Based on DEM-CFD Coupling. Minerals, 16(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010024