An Efficient Zircon Separation Method Based on Acid Leaching and Automated Mineral Recognition: A Case Study of Xiugugabu Diabase

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background and Sample Description

2.1. Geological Background

2.2. Sample Description

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Materials

3.2. Traditional Zircon Separation-Mount Preparation-Dating Workflow

3.3. Integrated High-Efficiency Zircon Separation and Analysis Workflow

3.3.1. Separation Steps

3.3.2. Mount Preparation

3.3.3. Zircon Localization

3.3.4. LA-ICP-MS Zircon U-Pb Dating

4. Result and Discussion

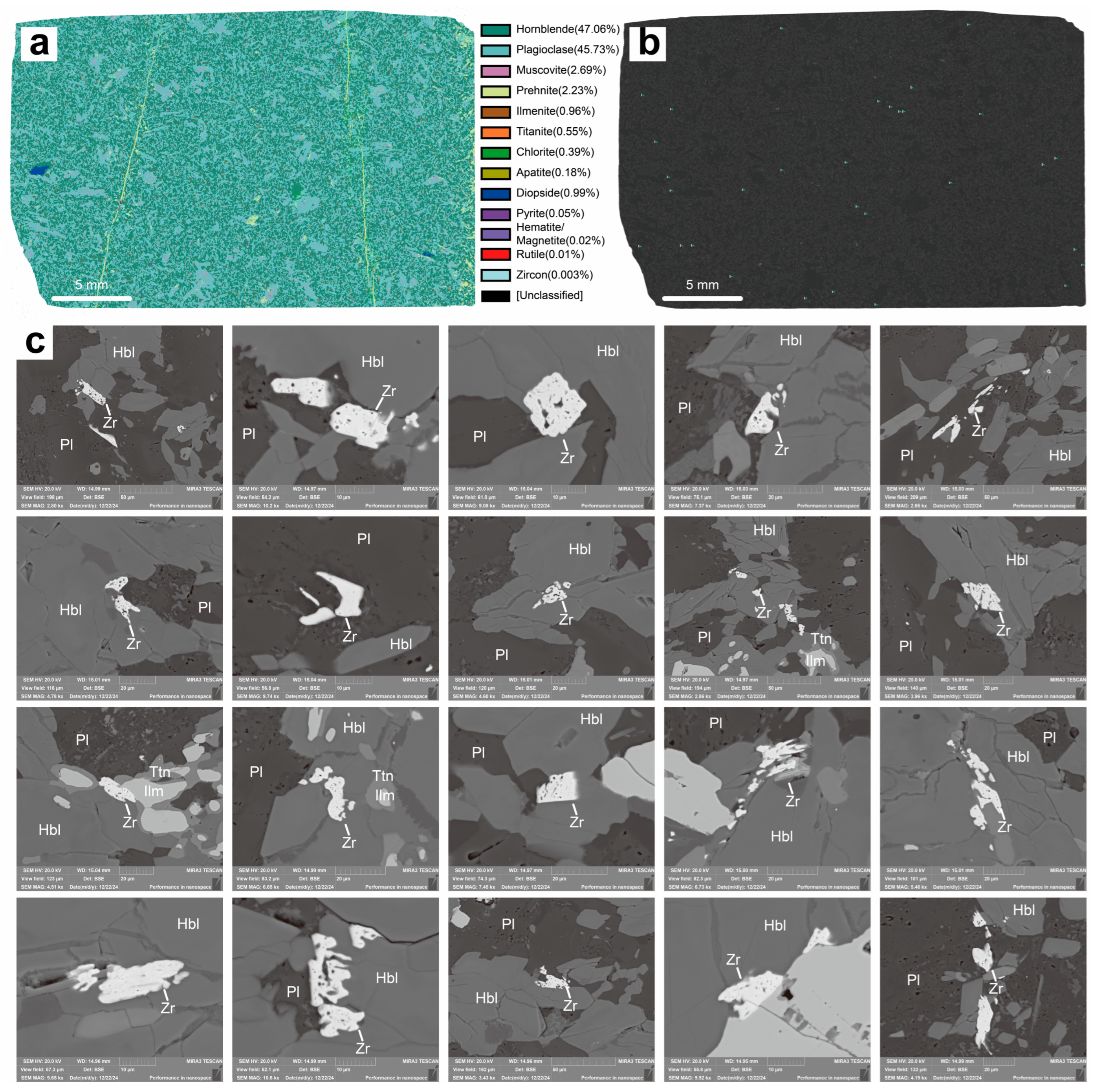

4.1. An Automated Workflow for Rapid and Unbiased Zircon Screening

4.2. A High-Purity, Low-Loss Mineral Separation Protocol

4.3. U-Pb Dating and Tectonic Implications

4.4. Advantages and Application Prospects of the Technical Workflow

5. Conclusions

- This study successfully establishes and validates an integrated technical workflow that combines multi-stage acid digestion (HF + HNO3 + HCl → aqua regia + H3BO3), powder stirring for mount preparation, automated mineral identification (TIMA), and in situ LA–ICP–MS dating. This approach effectively overcomes the sample bias and low analytical efficiency that exist in traditional zircon separation methods, particularly when applied to mafic-ultramafic rocks with low zircon abundance (>65 ppm).

- The new workflow achieves high-purity separation with minimal sample loss. In terms of cleanliness, it eliminates contamination-prone steps found in traditional methods by employing only a jaw crusher, agate mortar grinding, and analytical-grade acid dissolution, thereby avoiding U–Pb isotopic and metallic impurity contamination. In terms of sample loss, it only requires a small amount of powder, making it applicable to scarce samples such as drill cores and small outcrop samples.

- Applying this workflow to the Xiugugabu diabase from the western segment of the Yarlung–Tsangpo Suture Zone in southern Tibet yielded weighted mean 206Pb/238U ages of 120.5 ± 3.3 Ma (MSWD = 0.13) and 120.5 ± 2.0 Ma (MSWD = 3.2) for two samples. This result is highly consistent with the known formation ages (130–110 Ma) of other diabases in the suture zone, confirming the feasibility of the technical workflow.

- This technical workflow exhibits excellent stability and expandability. It meets the needs of large-scale geochronological surveys of mafic–ultramafic rocks and also supports combined analysis of zircon Hf isotopes and trace elements. This protocol provides multi-dimensional “chronological–geochemical” constraints for studies on rock formation ages, material sources, and tectonic evolution processes, representing a significant advancement for the geochronological research of low-abundance accessory minerals.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.F.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.L.; Wu, L.G.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Wei, G.J.; Zhang, W.F. Progress and prospects of radiometric geocheonology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2022, 96, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compston, W.; Williams, I.S.; Meyer, C. U–Pb geochronology of zircons from lunar breccia 73217 using a sensitive high mass-resolution ion microprobe. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1984, 89, B525–B534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.B.; Harrison, T.M. Zircon saturation revisited: Temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1983, 64, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. A Method for Separating and Purifying Zircon from Mafic Rocks. CN 100336731C, 12 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Li, Q.L.; Chu, Z.Y.; Ling, X.X.; Guo, S.; Xue, D.S.; Yin, Q.Z. An Acid-Based Method for Highly Effective Baddeleyite Separation from Gram-Sized Mafic Rocks. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 3634–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderlund, U.; Johansson, L. A simple way to extract baddeleyite (ZrO2). Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2002, 3, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, T.; Fei, C.H.; Guo, S.; Li, Q.L. Progress in techniques and methods for uncontaminated and highly efficient separation of zircon from geological samples. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2023, 39, 2857–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, H.L.; Wang, G.G.; Sun, J.D. Geochronology of the Baishi W-Cu Deposit in Jiangxi Province and Its Geological Significance. Minerals 2022, 12, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, W.L.; Yang, J.K.; Hu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, G.S. Principle of automated mineral quantitative analysis system and its application in petrology and mineralogy: An example from TESCAN TIMA. Miner. Depos. 2021, 40, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, D.H.; Luo, X.; Yuan, W.; Cai, H.G.; Zhang, H.; Feng, X.D.; Guo, S.; Li, W.H.; et al. Enrichment of Al-Li-Ga-Nb(Ta)-Zr(Hf) in the Permo-Carboniferous coal-bearing sequences of the Jungar Coalfield, northern China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 303, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.W.; Li, L.F.; Liu, P.R.; Wang, L.; Xia, Q.; Luo, J.C. An assessment of weathering in sandstone masonry built with earthen mortars: The case of the ancient rope Bridge Ferry, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 84, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilay, G.; Kuşcu, L.; Danišík, M. Application of (U-Th)/He hematite geochronology to the Çaldağ lateritic Ni-Co deposit, Western Anatolia: Implications for multi-stage weathering events during interglacial periods/segments. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 172, 106203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shu, Q.H.; Lentz, D.R.; Wang, Q.F.; Zhang, R.Z.; Niu, X.D.; Zeng, Q.W.; Xing, K.; Deng, J. Scheelite texture and composition fingerprint skarn mineralization of the giant Yuku Mo-W deposit, Central China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 175, 106361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.H.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.F.; Jin, T.K. A Safe and Efficient Method for Separation and Identification of Heavy Minerals. CN 115598159 B, 28 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hrstka, T.; Gottlieb, P.; Skala, R.; Breiter, K. Automated mineralogy and petrology-applications of TESCAN Integrated Mineral Analyzer (TIMA). J. Geosci. 2018, 63, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bea, F.; Bortnikov, N.; Cambeses, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Molina, J.F.; Montero, P.; Morales, I.; Silantiev, S.; Zinger, T. Zircon crystallization in low-Zr mafic magmas: Possible or impossible? Chem. Geol. 2022, 602, 120898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.S.; Wu, W.W.; Lian, D.Y.; Rui, H.C. Peridotites, chromitites and diamonds in ophiolites. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.L.; Yang, J.S.; Castro, A.I.L.; Feng, G.Y.; Li, Z.L.; Liu, F. Zircon ages, mineralogy, and geochemistry of ophiolitic mafic and island-arc rocks from central Cuba: Implications for Cretaceous tectonics in the Caribbean region. Lithos 2022, 434–435, 106924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, C.Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.Q.; Ji, W.B. Decoupled Trace Element and Isotope Compositions Recorded in Orthopyroxene and Clinopyroxene in Composite Pyroxenite Veins from the Xiugugabu Ophiolite (SW Tibet). J. Petrol. 2022, 63, egac046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.J.; Majka, J.; Lian, D.Y.; Yang, J.S.; Wang, L.; Ma, H.T.; Rui, H.C.; Bo, R.Z.; Masoud, A.E. Large-scale impregnation of oceanic and continental slab-derived adakitic melts into the mantle wedge. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, D.Y.; Liu, F.; Cai, P.J.; Wu, W.W.; Li, J.; Majka, J.; Xu, Z.Q.; Yang, J.S. Osmium and zinc isotope constraints on the origin of chromitites from the Yarlung-Zangbo ophiolites, Tibet, China. Miner. Depos. 2024, 59, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, D.Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, J.S.; Xu, Z.Q.; Wu, W.W. Fingerprints of the Kerguelen Mantle Plume in Southern Tibet: Evidence from Early Cretaceous Magmatism in the Tethyan Himalaya. J. Geol. 2021, 129, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, D.Y.; Yang, J.S.; Liu, F.; Wu, W.W.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; Huang, J. Geochemistry and tectonic significance of the Gongzhu peridotites in the northern branch of the western Yarlung Zangbo ophiolitic belt, western Tibet. Mineral. Petrol. 2017, 111, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Harrison, T.M. Geologic evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2000, 28, 211–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, C.Z.; Bénard, A.; Müntener, O.; Ji, W.B.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, W.Q.; Wu, F.Y. Heterogeneous mantle beneath the Neo-Tethys Ocean revealed by ultramafic rocks from the Xiugugabu Ophiolite in the Yarlung-Tsangpo Suture Zone, southwestern Tibet. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2023, 178, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.X. Experimental Study on Single Mineral Separation of Granulite from Laoniugou, Huadian. Jilin Geol. 1983, 4, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Shi, Y.; Anderson, J.L.; Ubide, T.; Nemchin, A.A.; Caulfield, J.; Wang, X.C.; Zhao, J.X. Dating mafic magmatism by integrating baddeleyite, zircon and apatite U–Pb geochronology: A case study of Proterozoic mafic dykes/sills in the North China Craton. Lithos 2020, 380–381, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.Q. Study on the Problems of Single Mineral Separation Science. Miner. Depos. Geol. 1990, 1, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Tan, K.X. Signal mineral separate method and its significance in geotectonics-taking apatite and zircon as examples. Geotecton. Metallog. 1998, 22, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, K.R.; Schmitt, A.K.; Swapp, S.M.; Harrison, T.M.; Swoboda-Colberg, N.; Bleeker, W.; Peterson, T.D.; Jefferson, C.W.; Khudoley, A.K. In situ U–Pb SIMS (IN-SIMS) micro-baddeleyite dating of mafic rocks: Method with examples. Precambrian Res. 2010, 183, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.M.; Jiang, S.Y.; Shao, J.B.; Zhang, D.Y.; Wu, X.K.; Huang, X.Q. New identification and significance of Early Cretaceous mafic rocks in the interior South China Block. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.X.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhao, J.H. Zircon U/Pb dating and Hf-O isotopes of the Zhouan ultramafic intrusion in the northern margin of the Yangtze Block, SW China: Constraints on the nature of mantle source and timing of the supercontinent Rodinia breakup. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2013, 58, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, C.; Woodhead, J.D.; Hellstrom, J.C.; Hergt, J.M.; Greig, A.; Maas, R. Improved laser ablation U-Pb zircon geochronology through robust downhole fractionation correction. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2010, 11, Q0AA06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Cho, H.C.; Kwon, J.H. Beneficiation of coal pond ash by physical separation techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 104, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, F.H.; Yang, J.S.; Liang, F.H.; Ba, D.Z.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Zircon U-Pb ages of the Dongbo ophiolite in the western Yarlung Zangbo suture zone and their geological significances. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2011, 27, 3223–3238. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.S.; Liu, Z.F.; Hébert, R. The Yarlung-Zangbo paleo-ophiolite, southern Tibet: Implications for the dynamic evolution of the Yarlung-Zangbo Suture Zone. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2000, 18, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Huang, Q.T.; Kapsiotis, A.; Xia, B.; Yin, Z.X.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, Y.; Shi, X.L. Early cretaceous ophiolites of the Yarlung Zangbo Suture Zone: Insights from dolerites and peridotites from the Baer upper mantle suite, SW Tibet (China). Int. Geol. Rev. 2017, 59, 1471–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Main Operation | Purpose | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Jaw crushing | Crush bulk rock samples into coarse fragments (<5 mm) using a jaw crusher, avoiding over-crushing that can fracture zircon grains. | Reduce sample particle size for subsequent fine crushing. | [6,7,26] |

| 2. Roll crushing | Further reduce the jaw-crushed fragments using a stainless-steel roll crusher; sieve the material through an 80–mesh nylon sieve (0.16 mm aperture), returning oversize particles for repeated crushing to ensure uniform particle size. | Refine sample to below 80 mesh for heavy mineral enrichment. | [6,26,27] |

| 3. Panning | Use a brass pan with ultrapure water (flow rate: 1–2 L/min) at a pan angle of 15–20°. Repeat the process 5–8 times. | Enrich heavy minerals (density > 2.9 g/cm3), including zircon, and remove light minerals (e.g., quartz and feldspar). | [5,6,7] |

| 4. Magnetic separation | Dry the enriched heavy minerals and pass them through a magnetic separator. | Remove strongly magnetic minerals (e.g., magnetite, pyrrhotite) and retain non-magnetic/weakly magnetic zircon. | [6,28,29] |

| 5. Purification | Hand-pick zircon grains under a stereomicroscope using a tungsten needle, selecting grains based on adamantine luster, short prismatic crystal habit, and high hardness, remove impurities (e.g., monazite, apatite) | Obtain high purity zircon grains (>95%). | [5,7,27,30] |

| 6. Mount preparation and imaging | Arrange zircon grains evenly in a mold (diameter: 1.5 cm), inject epoxy resin, and cure at 60 °C for 4–6 h. Capture morphological images using a transmitted–reflected microscope, and then take CL images using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). | Observe the external morphology and internal structure of zircon grains to select optimal locations for dating. | [7,27,31,32] |

| 7. Dating | Perform U–Pb dating using LA–ICP–MS. | Obtain zircon U–Pb age. | [27,31,32,33] |

| Phase | DQ11-6-1 | DQ11-6-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Ilmenite | 37,137 | 2706 |

| Quartz | 635 | 1048 |

| Rutile | 494 | 38 |

| Zircon | 255 | 41 |

| Calcite | 32 | 40 |

| Hematite/Magnetite | 50 | 24 |

| Barite | 51 | 0 |

| Diopside | 21 | 20 |

| Almandine | 29 | 7 |

| Muscovite | 14 | 19 |

| Plagioclase | 14 | 62 |

| Dolomite | 15 | 3 |

| Actinolite | 8 | 9 |

| Hornblende | 9 | 6 |

| Chlorite | 2 | 10 |

| Pyrite | 2 | 9 |

| Apatite | 5 | 2 |

| Illite | 6 | 0 |

| Biotite | 2 | 3 |

| Titanite | 1 | 0 |

| Monazite | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 38,782 | 4048 |

| Zircon | Rutile | Ilmenite | Dolomite | Hematite/ Magnetite | Pyrite | Quartz | Apatite | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain size/μm | DQ11-6-1 (%) | |||||||

| 3.30~15.03 | 37.72 | 62.55 | 14.89 | 41.06 | 20.13 | 30.30 | 10.86 | 29.35 |

| 15.03~17.05 | 16.83 | 5.00 | 8.29 | 22.22 | 5.28 | 69.70 | 5.07 | 23.91 |

| 17.05~19.35 | 15.56 | 6.59 | 9.21 | 0.00 | 7.31 | 0.00 | 4.56 | 0.00 |

| 19.35~21.95 | 8.93 | 4.28 | 10.94 | 36.71 | 5.84 | 0.00 | 4.92 | 0.00 |

| 21.95~24.91 | 13.51 | 5.40 | 13.01 | 0.00 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 5.69 | 46.74 |

| 24.91~28.26 | 5.44 | 0.00 | 11.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.36 | 0.00 |

| 28.26~32.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 10.83 | 0.00 | 6.57 | 0.00 | 3.82 | 0.00 |

| 32.07~36.39 | 2.01 | 0.00 | 8.51 | 0.00 | 7.39 | 0.00 | 4.91 | 0.00 |

| 36.39~41.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.78 | 0.00 | 9.74 | 0.00 | 10.28 | 0.00 |

| 41.28~46.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.67 | 0.00 |

| 46.84~113.42 | 0.00 | 16.19 | 3.01 | 0.00 | 34.17 | 0.00 | 37.88 | 0.00 |

| 113.42~188.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Grain size/μm | DQ11-6-2 (%) | |||||||

| 3.30~15.03 | 14.53 | 79.39 | 10.15 | 0.00 | 20.53 | 23.81 | 4.71 | 0.00 |

| 15.03~17.05 | 12.27 | 0.00 | 6.29 | 0.00 | 8.54 | 27.38 | 2.16 | 15.04 |

| 17.05~19.35 | 9.83 | 0.00 | 8.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.77 | 0.00 |

| 19.35~21.95 | 9.49 | 0.00 | 11.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 48.81 | 2.99 | 0.00 |

| 21.95~24.91 | 15.84 | 20.61 | 13.59 | 25.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.97 | 0.00 |

| 24.91~28.26 | 31.16 | 0.00 | 13.67 | 31.73 | 11.18 | 0.00 | 5.07 | 0.00 |

| 28.26~32.07 | 6.88 | 0.00 | 14.58 | 42.79 | 31.91 | 0.00 | 4.60 | 0.00 |

| 32.07~36.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.67 | 84.96 |

| 36.39~41.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.27 | 0.00 | 27.85 | 0.00 | 8.06 | 0.00 |

| 41.28~46.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.75 | 0.00 |

| 46.84~113.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 43.13 | 0.00 |

| 113.42~188.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.11 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yuan, Q.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Cai, P.; Zhao, J.; Yan, W.; Hamit, F.; Wang, R.; Chen, Z.; Wang, A.; et al. An Efficient Zircon Separation Method Based on Acid Leaching and Automated Mineral Recognition: A Case Study of Xiugugabu Diabase. Minerals 2026, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010020

Yuan Q, Li H, Wu Y, Cai P, Zhao J, Yan W, Hamit F, Wang R, Chen Z, Wang A, et al. An Efficient Zircon Separation Method Based on Acid Leaching and Automated Mineral Recognition: A Case Study of Xiugugabu Diabase. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Qiuyun, Haili Li, Yue Wu, Pengjie Cai, Jiadi Zhao, Weihao Yan, Ferdon Hamit, Ruotong Wang, Zhiqi Chen, Aihua Wang, and et al. 2026. "An Efficient Zircon Separation Method Based on Acid Leaching and Automated Mineral Recognition: A Case Study of Xiugugabu Diabase" Minerals 16, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010020

APA StyleYuan, Q., Li, H., Wu, Y., Cai, P., Zhao, J., Yan, W., Hamit, F., Wang, R., Chen, Z., Wang, A., & Masoud, A. E. (2026). An Efficient Zircon Separation Method Based on Acid Leaching and Automated Mineral Recognition: A Case Study of Xiugugabu Diabase. Minerals, 16(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010020