Abstract

The balanced hypercube network, which is a novel interconnection network for parallel computation and data processing, is a newly-invented variant of the hypercube. The particular feature of the balanced hypercube is that each processor has its own backup processor and they are connected to the same neighbors. A Hamiltonian bipartite graph with bipartition is Hamiltonian laceable if there exists a path between any two vertices and . It is known that each edge is on a Hamiltonian cycle of the balanced hypercube. In this paper, we prove that, for an arbitrary edge e in the balanced hypercube, there exists a Hamiltonian path between any two vertices x and y in different partite sets passing through e with . This result improves some known results.

1. Introduction

Interconnection networks play an essential role in the performance of parallel and distributed systems. In the event of practice, large multi-processor systems can also be adopted as tools to address complex management and big data problems. It is well-known that an interconnection network is generally modeled by an undirected graph, in which processors are represented by vertices and communication links between them are represented by edges. The hypercube network is recognized as one of the most popular interconnection networks, and it has gained great attention and recognition from researchers both in graph theory and computer science. Nevertheless, the hypercube also has some shortcomings. For example, its diameter is large. Therefore, many variants of the hypercube have been put forward [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] to improve performance of the hypercube in some aspects. Among these variants, the balanced hypercube has the following special properties: each vertex of the balanced has a backup (matching) vertex and they have the same neighborhood. Therefore, the backup vertex can undertake tasks that originally run on a faulty vertex. It has been proved that the diameter of an odd-dimensional balanced hypercube is [10], which is smaller than that of the hypercube .

With regard to the special properties discussed above, the balanced hypercube has been investigated by many researchers. Huang and Wu [11] studied the problem of resource placement of the balanced hypercube. Xu et al. [12] showed that the balanced hypercube is edge-pancyclic and Hamiltonian laceable. It is found that the balanced hypercube is bipanconnected for all by Yang [13]. Huang et al. [14] discussed area efficient layout problems of the balanced hypercube. Yang [15] determined super (edge) connectivity of the balanced hypercube. Lü et al. studied (conditional) matching preclusion, hyper-Hamiltonian laceability, matching extendability and extra connectivity of the balanced hypercube in [16,17,18,19], respectively. Some symmetric properties of the balanced hypercube are presented in [20,21]. As stated above, the balanced hypercube possesses some desirable properties that the hypercube does not have, so it is interesting to explore other favorable properties that the balanced hypercube may have.

Since parallel applications such as image and signal processing are originally designed on array and ring architectures, it is important to have path and cycle embeddings in a network. Especially, Hamiltonian path and cycle embeddings and other properties of famous networks are extensively studied by many authors [12,13,22,23,24,25,26]. Xu et al. [12] proved that each edge of the balanced hypercube is on a cycle of even length from 4 to , that is, the balanced hypercube is edge-bipancyclic. They also showed that the balanced hypercube is Hamiltonian laceable for all integers . Recently, Lü et al. [17] further obtained that the balanced hypercube is hyper-Hamiltonian laceable for all integers .

2. Preliminaries

Let be a simple undirected graph, where V is a vertex-set of G and E is an edge-set of G. A path P from to is a sequence of vertices from to such that every pair of consecutive vertices are adjacent and all vertices are distinct except for and . We also denote the path by . The length of a path P is the number of edges in P, denoted by . A cycle is a path with at least three vertices such that the first vertex is the same as the last one. A graph is bipartite if its vertex-set can be partitioned into two subsets and such that each edge has its ends in different subsets. A graph is Hamiltonian if it possesses a spanning cycle. A graph is Hamiltonian connected if there exists a Hamiltonian path joining any two vertices of it. Obviously, any bipartite graph is not Hamiltonian connected. Simmons [27] proposed Hamiltonian laceability of bipatite graphs: a bipartite graph is Hamiltonian laceable if there exists a Hamiltonian path between any two vertices x and y in different partite sets of G. A graph G is hyper-Hamiltonian laceable if it is Hamiltonian laceable and, for any vertex , there exists a Hamiltonian path in between any pair of vertices in . For the graph definitions and notations not mentioned here, we refer the readers to [28,29].

Wu and Huang [10] gave the following definition of as follows.

Definition 1.

An n-dimensional balanced hypercube, denoted by , consists of vertices labelled by , where for each . Any vertex with of has the following neighbors:

- 1.

- ,, and

- 2.

- ,.

In , the first coordinate of vertex is called the inner index and the other coordinates are known as the i-dimensional index. Clearly, each vertex in has two inner neighbors, and other neighbors. Note that all of the arithmetic operations on indices of vertices in are four-modulated.

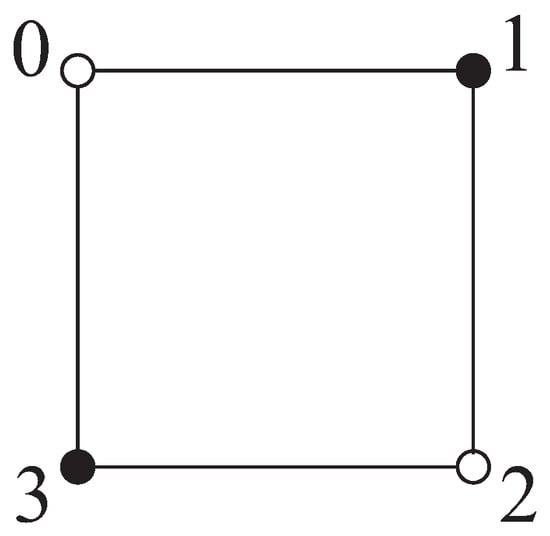

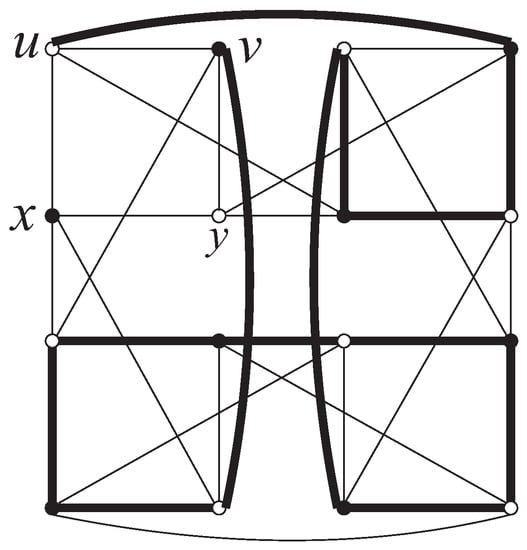

Figure 1.

.

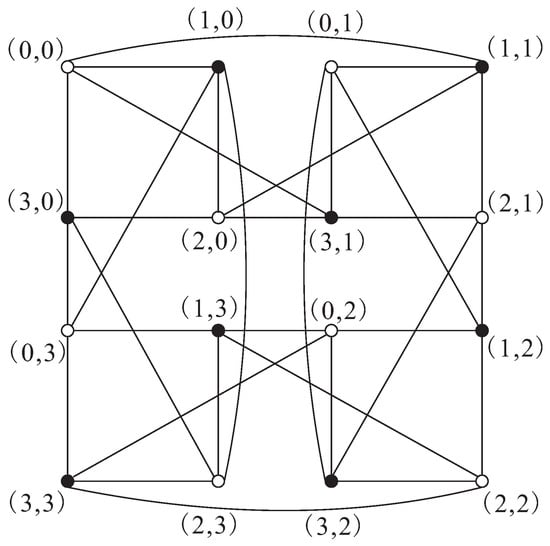

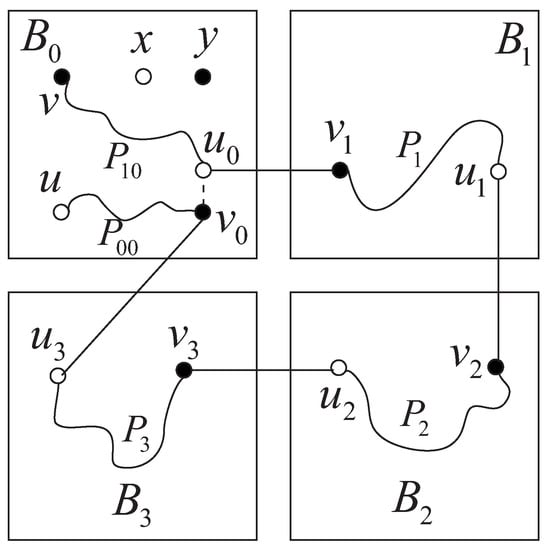

Figure 2.

.

In the following, we give some basic properties of .

Proposition 1.

[10] The balanced hypercube is bipartite.

Proposition 2.

[10,20] The balanced hypercube is vertex-transitive and edge-transitive.

Proposition 3.

[10] The vertices and mod 4, of have the same neighborhood.

3. Main Results

Firstly, we characterize edges of the . Let u and v be two adjacent vertices in . If u and v differ in only the inner index, then is said to be a 0-dimensional edge, and u is a 0-dimensional neighbor of v. If u and v differ in not only the inner index, but also some i-dimensional index () of the vertices, then is called an i-dimensional edge, and u is an i-dimensional neighbor of v. For convenience, we denote the set of all i-dimensional edges by (). Let () be the subgraph of induced by the vertices of with the -dimensional index i. That is, the ’s can be obtained from by deleting all -dimensional edges. Therefore, for each .

By Proposition 1, we know that is bipartite. We can use and to denote the two partite sets of such that and consist of vertices of with an even inner index and an odd inner index, respectively. For convenience, the vertices of and are colored white and black, respectively. Throughout this paper, we use and (resp. and ) to denote white (resp. black) vertices in ().

Lemma 1.

[16] In , can be divided into edge-disjoint 4-cycles for .

Lemma 2.

[12] The balanced hypercube is Hamiltonian laceable and edge-bipancyclic for .

Lemma 3.

[17] The balanced hypercube is hyper-Hamiltonian laceable for .

Lemma 4.

[30] Assume u and x are two different vertices in , and v and y are two different vertices in . Then, there exist two vertex-disjoint paths P and Q such that P joins x to y, Q joins u to v and , where .

Lemma 5.

Let be an integer. Suppose that and y are four distinct vertices differ only the inner index in . In addition, and . Then, there exists a Hamiltonian path from u to v in .

Proof.

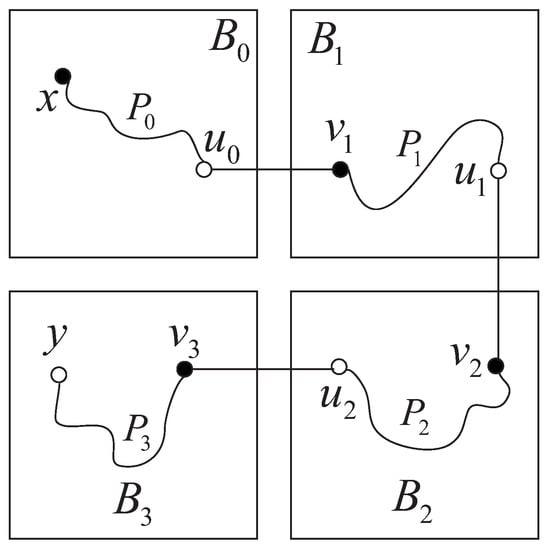

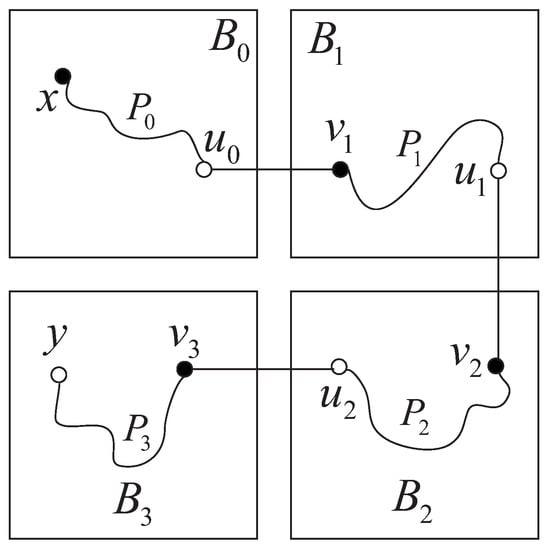

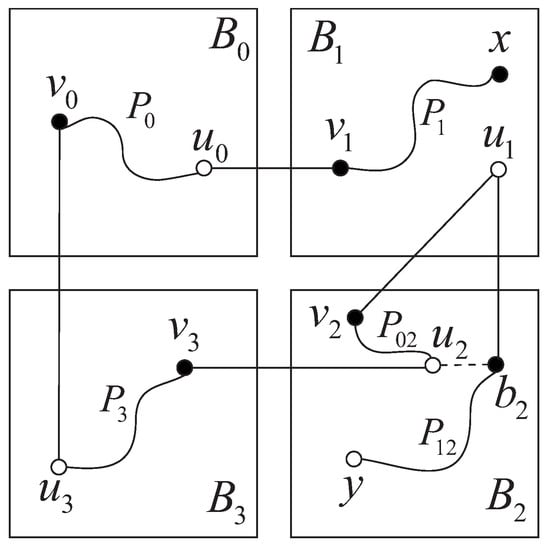

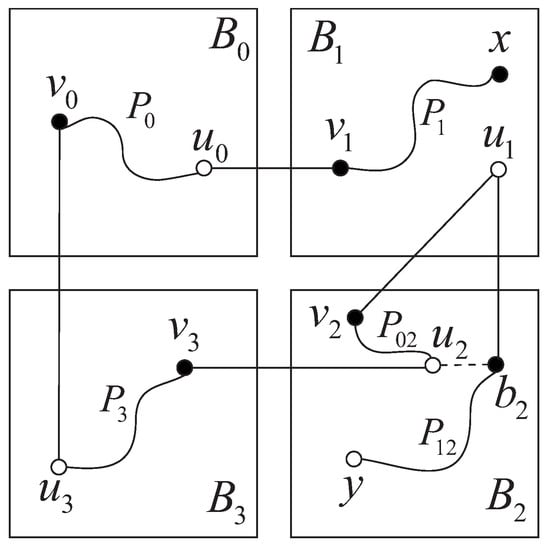

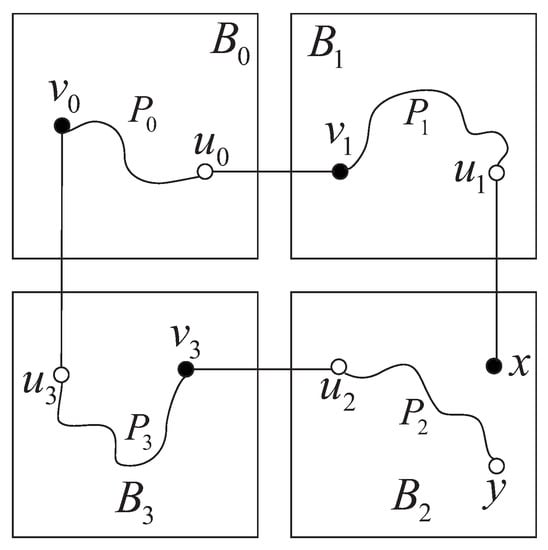

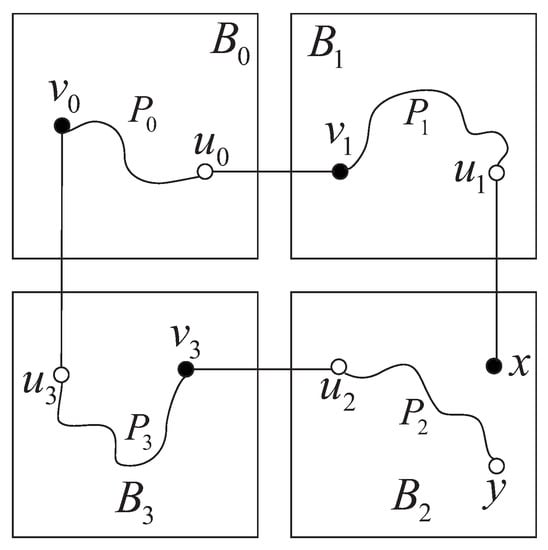

We proceed with the proof by the induction on n. First, we consider . Clearly, and y are in the same 4-cycle of . A Hamiltonian path of from u to v is shown in Figure 3. Thus, we suppose that the lemma holds for all integers with . Next, we consider . We split into four s by deleting -dimensional edges. For convenience, we denote the four s by , , and according to the last position of vertices in , respectively. Without loss of generality, we may assume that and y are in . By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path from u to v in . Let , where (resp. ) are neither end-vertex of . We denote the segment of from u to by , and the segment of from to v by . By Definition 1, (resp. ) has an -dimensional neighbor (resp. ) in (resp. ). Moreover, there exist an edge from to , and an edge from to . Therefore, there exist a Hamiltonian path from to in , a Hamiltonian path from to in , and a Hamiltonian path from to of . Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of (see Figure 4). ☐

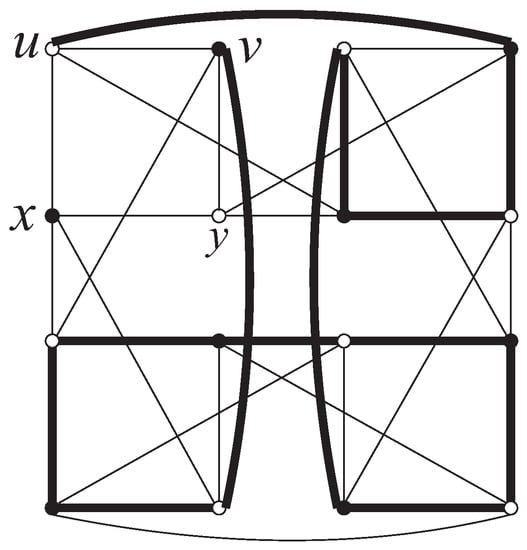

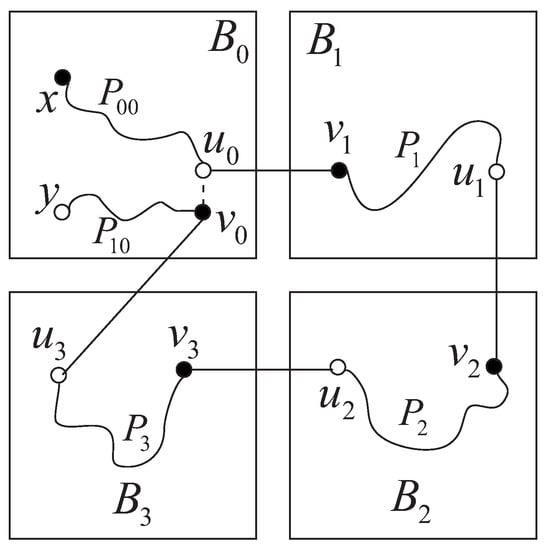

Figure 3.

A Hamiltonian path of .

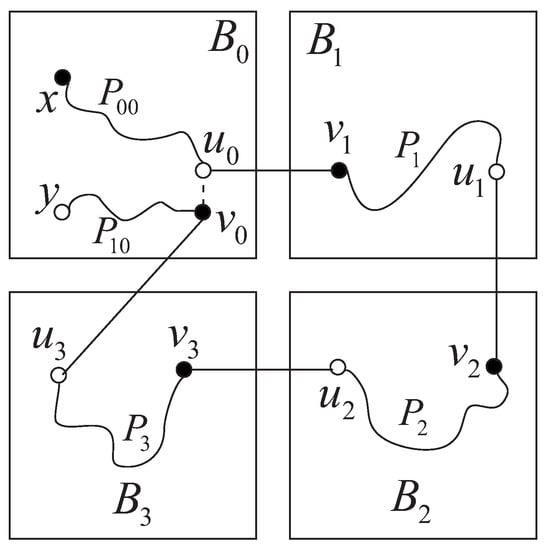

Figure 4.

A Hamiltonian path of .

Next, we present the following lemma as a basis of our main theorem.

Lemma 6.

Let e be an arbitrary edge in . In addition, let and be any two vertices in with . Then, there exists a Hamiltonian path between x and y passing through e.

Proof.

By Proposition 2, is vertex-transitive and edge-transitive, and we may suppose that . Obviously, if , then there exists no Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing e. Thus, at most, one of x and y is the end-vertex of e. We consider the following two cases:

Case 1:

Neither x nor y is incident to e. By the relative positions of x and y, and Proposition 3, we consider the following: (1) , ; (2) , ; (3) , ; (4) , ; (5) , ; (6) , ; (7) , ; (8) , ; (9) , ; (10) , . For simplicity, we list all Hamiltonian paths of the conditions above in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hamiltonian paths passing through e with neither x nor y being incident to e.

Case 2:

Either x or y is incident to e. Without loss of generality, suppose that x is incident to e, that is, . By Proposition 3, we need only to consider four conditions of y: (1) ; (2) ; (3) ; and (4) . Again, we list Hamiltonian paths of the conditions of x and y in this case in Table 2. ☐

Table 2.

Hamiltonian paths passing through e with x or y being incident to e.

Now, we are ready to state the main theorem of this paper.

Theorem 1.

Let be an integer and e be an arbitrary edge in . In addition, let and be any two vertices in with . Then, there exists a Hamiltonian path of between x and y passing through e.

Proof.

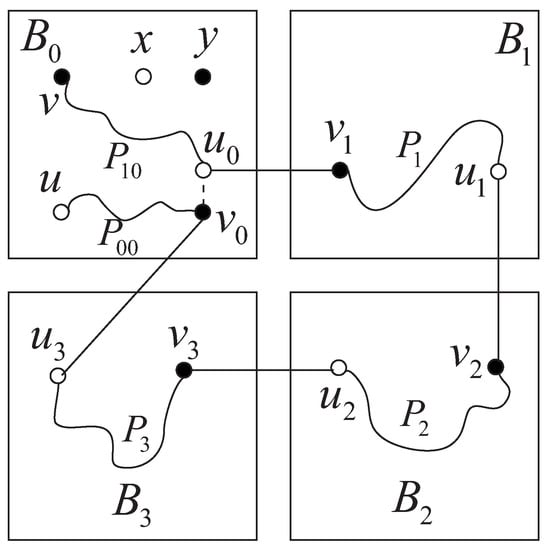

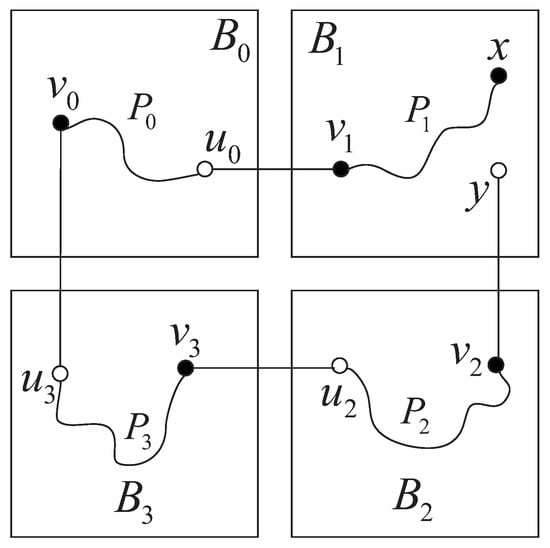

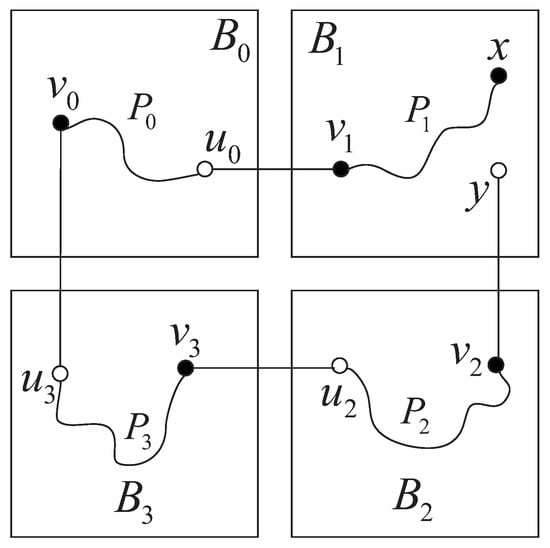

We prove this theorem by induction on n. By Lemma 6, we know that the theorem is true for . Therefore, we suppose that the theorem holds for with . Next, we consider . Firstly, we divide into () by deleting all -dimensional edges. For convenience, we denote by according to the last position of the vertices in for each . Similarly, suppose that . Let and be two distinct vertices in . By relative positions of x and y, we consider the following cases:

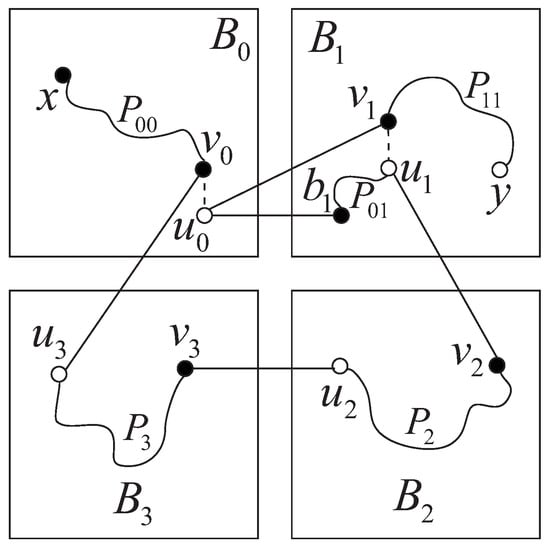

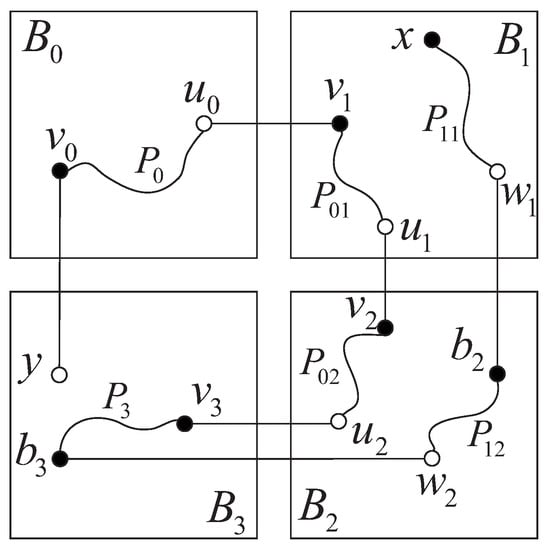

Case 1:

, . By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path from x to y of passing through e. Thus, there is an edge on such that is not adjacent to e and divides into two sections and , where connects x to and connects to y. Let (resp. ) be an ()-dimensional neighbor of (resp. ). By Definition 1, there exist an edge from to , and an edge from to . Thus, by Lemma 2, there exist a Hamiltonian path from to in , a Hamiltonian path from to in , and a Hamiltonian path from to in . Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Illustration for Case 1.

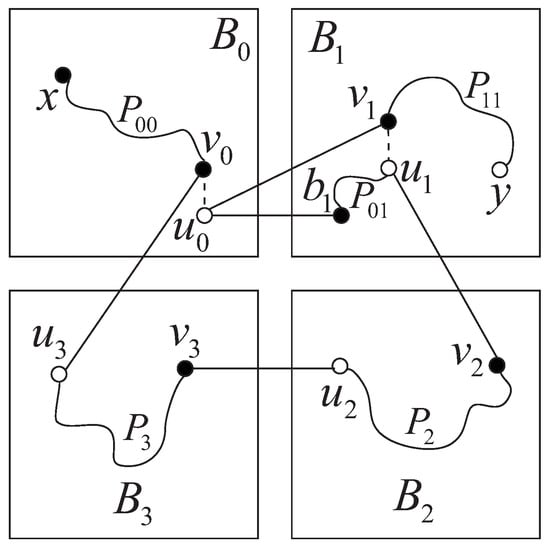

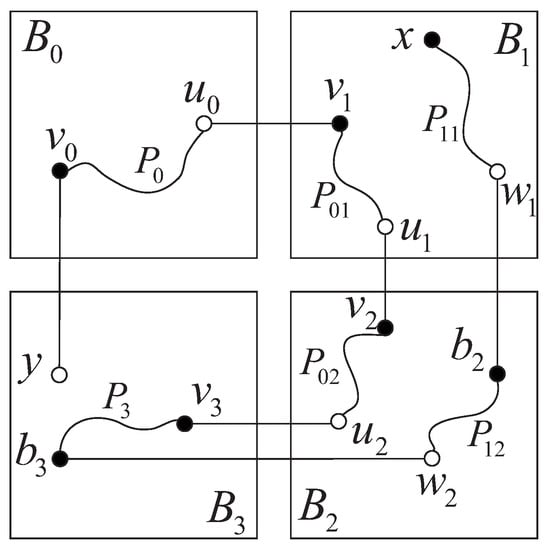

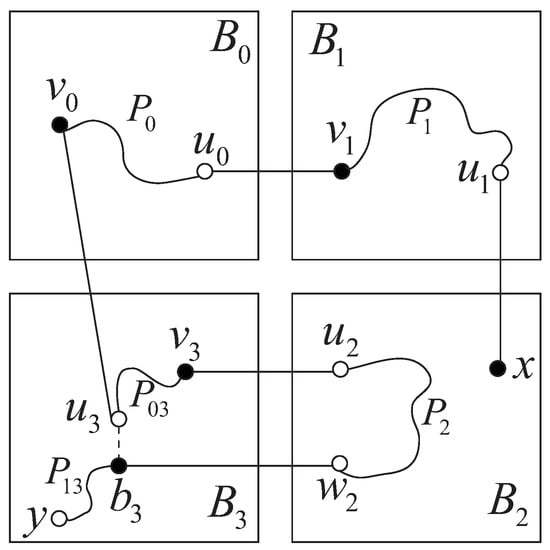

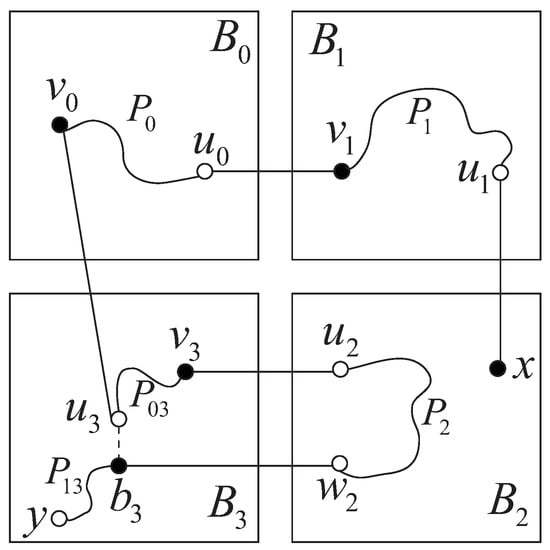

Case 2:

, . Let be a white vertex such that is not incident to e. By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from x to passing through e. Supposing that is a black vertex adjacent to on , we denote the segment of the path from x to by . Let the two -dimensional neighbors of be and . By Lemma 2, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to y. Let be the neighbor of in the section of from to . Then consists of two subpaths and , which connect to and to y, respectively. Let (resp. ) be an ()-dimensional neighbor of (resp. ). Furthermore, there exists an edge from to . Then, there exist a Hamiltonian path from to in , and a Hamiltonian path from to in . Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Illustration for Case 2.

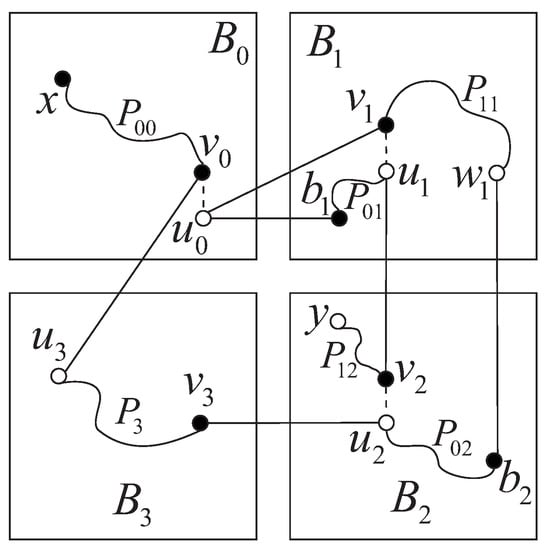

Case 3:

, . Let be a white vertex in not incident to e, and and be two -dimensional neighbors of . In addition, assume that is an arbitrary white vertex in . There exists a Hamiltonian path of from to . Thus, there exists an edge whose removal will lead to two disjoint subpaths and , where connects to and connects to . Let (resp. ) be an -dimensional neighbor of (resp. ). There also exists a Hamiltonian path of from y to via the edge . Deleting results in two disjoint paths and , where connects to and connects to y. By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from x to via the edge . For convenience, denote by , that is, connects x to . Let (resp. ) be an -dimensional neighbor of (resp. ). Again, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to . Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Illustration for Case 3.

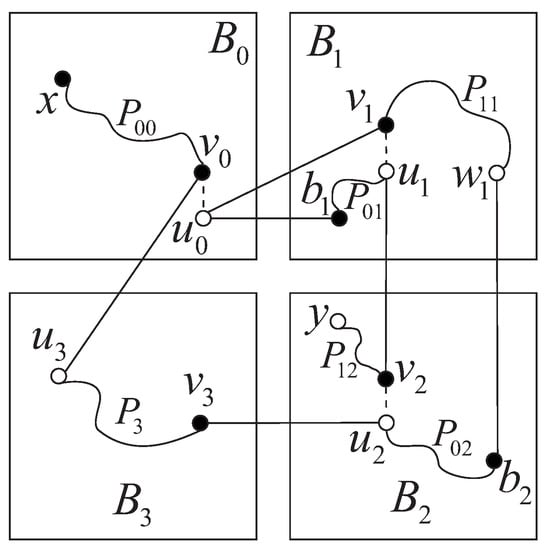

Case 4:

, . Let (resp. ) be a white (resp. black) vertex in (resp. ). There exist an edge from to , an edge from to , and an edge from to . By Lemma 2, there exist a Hamiltonian path of from to , a Hamiltonian path of from to , and a Hamiltonian path of from to . By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from x to passing through e. Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Illustration for Case 4.

Case 5:

, . Let be a black vertex in . By Lemma 3, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from x to . Furthermore, there exist an edge from to , an edge from to , an edge from to , and an edge from to . Moreover, there exist a Hamiltonian path of from to passing through e, a Hamiltonian path of from to , and a Hamiltonian path of from to . Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Illustration for Case 5.

Case 6:

, . Let (resp. ) be a black (resp. white) vertex in . By Lemma 3, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from x to . In addition, suppose that and are two -dimensional neighbors of . By Lemma 2, there exists a Hamiltonian of from to y via the edge . Thus, can be divided into three sections: , and , where connects to and connects to y. Furthermore, there exist an edge from to , an edge from to , and an edge from to . Therefore, there exist a Hamiltonian path of from to passing through e, and a Hamiltonian path of from to . Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Illustration for Case 6.

Case 7:

, . Let and be two black vertices in . Suppose that and are -dimensional neighbors of and , respectively. By Lemma 3, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to . By Definition 1, there exist two edges and from to , an edge from to , and an edge from to , where . By Lemma 4, there exist two vertex-disjoint paths and such that joins and , joins x and , and . Similarly, there exist two vertex-disjoint paths and such that joins and , joins and , and . By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to passing through e. Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Illustration for Case 7.

Case 8:

, . Let be an arbitrary white vertex. By Lemma 3, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to y. By Definition 1, there exist an edge from to , an edge from to , an edge from to , and an edge from to . Following Lemma 2, we can obtain a Hamiltonian path of from to , and a Hamiltonian path of from to . By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to passing through e. Therefore, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Illustration for Case 8.

Case 9:

, . Let and be two distinct white vertices in , and and be -dimensional neighbors of and , respectively. By Lemma 3, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to . By Lemma 2, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to y via the edge . By deleting , we can obtain two disjoint subpaths: and , where connects to and connects to y. Furthermore, there exist an edge from to , an edge from to , and an edge from to . By Lemma 2, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to . By an induction hypothesis, there exists a Hamiltonian path of from to passing through e. Hence, is a Hamiltonian path of from x to y passing through e (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Illustration for Case 9.

Case 10:

, . The proof is analogous to that of Case 5, and we omit it. ☐

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we study a type of path embedding of the balanced hypercube, and show that, for an arbitrary edge , there exists a Hamiltonian path between any two vertices x and y in different partite sets passing through e. This result also implies that each edge is on a Hamiltonian cycle of the balanced hypercube, which is part of the results of edge bipancyclicity of the balanced hypercube.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 61402210 and 60973137, Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University under Grant No. NCET-12-0250, Major Project of High Resolution Earth Observation System with Grant No. 30-Y20A34-9010-15/17, “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences with Grant No. XDA03030100, Gansu Sci.&Tech. Program under Grant Nos. 1104GKCA049, 1204GKCA061 and 1304GKCA018, The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grant No. lzujbky-2016-140, Gansu Telecom Cuiying Research Fund under Grant No. lzudxcy-2013-4, Google Research Awards and Google Faculty Award, China.

Author Contributions

Dan Chen and Chong Chen initiated the research idea and developed the models with contributions from Gaofeng Zhang. Zhongzhou Lu and Zebang Shen offered help while constructing the model. The manuscript was written by Dan Chen and Chong Chen with Rui Zhou and Qingguo Zhou providing review and comments. All the authors were engaged in the final manuscript preparation and agreed to the publication of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abraham, S.; Padmanabhan, K. The twisted cube topology for multiprocessors: A study in network asymmetry. J. Parall. Distrib. Comput. 1991, 13, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudum, S.A.; Sunitha, V. Augmented cubes. Networks 2002, 40, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, P.; Larson, S.M. The Möbius cubes. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1995, 44, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, W.J. Performance analysis of k-ary n-cube interconnection networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1990, 39, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, K. The crossed cube architecture for parallel computation. IEEE Trans. Parall. Distr. Syst. 1992, 3, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-amawy, A.; Latifi, S. Properties and performance of folded hypercubes. IEEE Trans. Parall. Distrib. Syst. 1991, 2, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.K.; Tan, J.J.M.; Hsu, L.H.; Sung, T.Y. The shuffle-cubes and their generalization. Inform. Process. Lett. 2001, 77, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preparata, F.P.; Vuillemin, J. The cube-connected cycles: A versatile network for parallel computation. Comput. Arch. Syst. 1981, 24, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Stewart, I.A. Augmented k-ary n-cubes. Inform. Sci. 2011, 181, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, K. The balanced hypercube: A cube-based system for fault-tolerant applications. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1997, 46, 484–490. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Wu, J. Fault-tolerant resource placement in balanced hypercubes. Inform. Sci. 1997, 99, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Hu, H.; Xu, J. Edge-pancyclicity and Hamiltonian laceability of the balanced hypercubes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 189, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Bipanconnectivity of balanced hypercubes. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 60, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Wu, J. Area efficient layout of balanced hypercubes. Int. J. High Speed Electr. Syst. 1995, 6, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Super connectivity of balanced hypercubes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 219, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. Matching preclusion for balanced hypercubes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2012, 465, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, H.; Zhang, H. Hyper-Hamiltonian laceability of balanced hypercubes. J. Supercomput. 2014, 68, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, H.; Gao, X.; Yang, X. Matching extendability of balanced hypercubes. Ars Combinatoria 2016, 129, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, H. On extra connectivity and extra edge-connectivity of balanced hypercubes. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2017, 94, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-X.; Wu, Z.-L.; Yang, S.-C.; Yuan, K.-W. Symmetric property and reliability of balanced hypercube. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2015, 64, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-X.; Kwak, J.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Wu, Z.-L. Automorphism group of the balanced hypercube. Ars Math. Contemp. 2017, 12, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, P.K.; Prasad, R. Hamiltonian decomposition of the rectangular twisted torus. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2012, 23, 1504–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.-W.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Hsieh, S.-Y. On 3-extra connectivity and 3-extra edge connectivity of folded hypercubes. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2014, 63, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.-Y.; Yu, P.-Y. Fault-free mutually independent Hamiltonian cycles in hypercubes with faulty edges. J. Combin. Optim. 2007, 13, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Chwa, K. Hamiltonian properties on the class of hypercube-like networks. Inform. Process. Lett. 2004, 91, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Wang, R. Hamiltonian paths and cycles with prescribed edges in the 3-ary n-cube. Inform. Sci. 2011, 181, 3054–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G. Almost all n-dimensional rectangular lattices are Hamilton–Laceable. Congr. Numer. 1978, 21, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- West, D.B. Introduction to Graph Theory, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.M. Topological Structure and Analysis of Interconnection Networks; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D.; Hao, R.-X.; Feng, Y.-Q. Two node-disjoint paths in balanced hypercubes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 242, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).