1. Time and Gravity

Time has been a mystery to mankind for thousands of years, surely since the very start of natural philosophy. Understanding the nature of time seems indeed fundamental to understand reality. The understanding of time has evolved a lot since the Greeks (For example, for Aristotle, time is not fundamental but only a derived concept from the notion of space and motion [

1]), passing from being an absolute (observer independent) characteristic of space-time as in Galilean relativity to a observer dependent entity in Special Relativity. Finally, the common modern point of view on time is mostly based on Einstein’s theory of General Relativity (GR).

More precisely, in the early XXth century, following the works by Minkowski and Einstein, time has been unified with Space into the concept of space-time. The latter is geometrically described by a (four dimensional) manifold, that is, a topological space equipped with a differential structure, together with a metric

[

2]. In all the metric theories of gravity (in particular GR), the metric describes the dynamical degrees of freedom encoding gravity (although in metric affine theories the connection also plays a role in the definition of the gravitational field).

A metric is characterized by a signature, that is the number of its positive and negative eigenvalues. (For non-metric theories, the signature can be tracked back in the inner product in the tangent space. The signature is usually not a dynamical object, i.e., it is a background structure.) We shall use here the terminology Lorentzian for the case and Riemannian for the one . A Lorentzian signature allows one to define space-like (), light-like () and time-like distances (). A time-like geodesic is interpreted as the trajectory of a massive test particle moving in space-time. Distances along this geodesic are usually interpreted as the proper time of the particle, that is, the time measured by a clock attached to the particle. In the case of a Riemannian signature , one can not then talk about time at all since we have only space-like distances (). The notion of signature is therefore an essential part of the notion of “time”.

So far we have considered the textbook definition of time in metric theories of gravity. However the situation is clearly more subtle than that. Indeed, physical phenomena do possess an intrinsic irreversibility. This irreversibility can have a thermodynamical origin due to the natural coarse-grained description of Nature. It can be also tracked back from the quantum mechanical nature of matter fields (putting aside the issue of quantum gravity for a moment). Indeed the basic axioms of quantum mechanics impose a one-way direction in time evolution: Measurement process induces a collapse of the wave-function which cannot be undone going backward in time. Using the words of Ellis [

3], there is an “eternal becoming”, which pinpoints not only the time direction, but also its arrow. However, it is also true that, when confronted with the most daunting solutions of the Einstein equations, this more elaborate intuition about the nature of time seems at least severely challenged: GR does allow for solutions which contain closed time-like loops (e.g., Gödel universe) and hence time machines (see e.g., [

4]). More generally, time-orientability of space-time does not seem to be a built-in property of the theory.

With respect to these puzzling aspects of General Relativity one can have at least two antithetic points of views. The first, the one most pursued so far, is that time-machine solutions (and other “time-menacing” features) of GR are just a sign of the limits of the theory [

4], and that a quantum gravity theory should resolve these issues (among others such as the singularities issue). On the other hand, one may conjecture that these riddling solutions are just warning bells that our notion of time may not be fundamental; possibly whatever lies beyond General Relativity (and its related notion of space-time manifold) may not include time as we know it as a fundamental structure. (All in all, it is well known that whenever chronological horizons arise, quantum field theory in curved space-time also breaks down (Kay–Radzikowsky–Wald theorem [

5]), and quantum gravity has to be called in, in order to make any prediction.)

However, given that even in GR the notion of time as “time-arrow” is problematic, we shall focus here on the emergence of time in the sense of Lorentzian signature emerging from a Riemannian one. More specifically, in this short essay we want to discuss the possibility that space-time and its dynamics, e.g., GR, are all emergent at the same level from some timeless fundamental, non-gravitational, theory. In order to do so, however, we shall have to start from some simpler gravitational theory than GR, and in particular we shall work with scalar fields and a scalar theory of gravitation,

i.e., Nordström gravity [

6].

Historically, the first relativistic version of gravitational dynamics was proposed by Nordström, who in 1913 tried to generalize the Poisson equation, while preserving, following Einstein’s advice, both what would later be called the strong equivalence principle [

7], and the intrinsic non-linearity of the gravitational interaction. After some years, Nordström finally succeeded, and his gravity theory (minimally coupled to a scalar field

) was later described in a geometric way by Einstein and Fokker as follows

where

is the trace of the stress energy tensor

, defined with respect to

, for the matter field

,

is the Ricci scalar for

and

is proportional to the Newton constant

. Equation (

1) encodes the fact that the Weyl tensor

is zero,

i.e., that the metric

is conformally flat. Equations (

1) and (

2) are called the Einstein–Fokker equations. (Note that this is almost the same, modulo a minus sign, as the trace of the Einstein equation restricted to the conformal metric.) Albeit much simpler than GR, it is important to stress that Nordström gravity is a consistent theory of gravitation and that it shares many features with GR. Most importantly, it does satisfy the strong equivalence principle and is diffeomorphisms invariant. It is however clearly not physical since fields which are described by conformally invariant equations of motion will always move as in flat space-time. This theory is hence unable to detect observed phenomena such as the bending of light by gravitational fields. Furthermore its diffeomorphisms invariance is obtained at the cost of background independence, given that in this case, in addition to topology and signature, another background structure is introduced, namely the Minkowski metric. Let us nonetheless take this simpler theory of gravity as our target and show how time and gravity may emerge at the same level.

2. Is the Notion of Time Really Fundamental?

Before embarking on the specific discussion about the emergence of time, let us make a small detour explaining what “emergence” means, starting from the very well understood case of condensed matter.

In condensed matter systems, the macroscopic properties of a system are determined by the way in which the microscopical degrees of freedom (e.g., the atoms) are organized. However, the micro- and macro-worlds cannot be connected in an easy way: It can be a daunting task to derive macro equations from micro equations. Conversely, in general it is difficult to derive the micro-physics from macro-physics.

For example, water is described by hydrodynamic equations. Quantizing these equations will not provide the correct fundamental micro-physics. One needs to be aware of the existence of atoms to be able to propose a satisfying fundamental theory for water. On the other hand it is a difficult task to obtain the hydrodynamic equations from the Schrödinger equation encoding the dynamics of the hydrogen and oxygen atoms. This example illustrates how the fundamental dynamics (i.e., here described by the Schrödinger equation) can be qualitatively different from the “emerging” dynamics (i.e., here the hydrodynamic equations). It emphasizes also how the macroscopic or “emergent” degrees of freedom (fluid) have different properties than the microscopic degrees of freedom (atoms).

Roughly speaking, an “emergent theory” is obtained by proceeding to a large large

N limit for some class of degrees of freedom in the fundamental theory. It is often the case that the resulting theory shows properties qualitatively different from the ones of the fundamental theory. A typical way to construct such an emergent theory is to condense all the relevant properties in some macroscopical/coarse-grained variables which somehow encode the universal properties of the large number system without entering into the details of the microscopic dynamics. While the detailed description of macroscopic dynamics would be only approximate, one can still discuss some of its essential features. For instance, a Bose–Einstein condensate is described by a nonlinear Schrödinger equation for a classical complex scalar field describing the mean field condensate wave function, rather than from the n-body quantum state describing all the atoms in the condensate [

8]. Despite this very simple description, the phenomenon of condensation and the properties of the quasi-particles are correctly predicted. Note that this description is only an approximation, valid only in a given regime. When getting beyond the regime, one has to take into account the fundamental theory instead of the emerging theory.

One could expect a similar situation to happen in the context of Quantum Gravity. (We assume here that the fundamental theory behind gravity is obtained by quantization of the relevant degrees of freedom. This assumption could be wrong if the quantum theory is

per se an emergent notion too, see for instance [

9] and references therein.) Einstein equations could be the analogue of some type of hydrodynamic equations. Even if a Quantum Gravity theory was fully available, the derivation of Einstein equations from the fundamental equations of Quantum Gravity would then be something extremely nontrivial, such as in the case of water for example. Moreover, this would indicate also that the fundamental Quantum Gravity theory has probably nothing to do with (quantum) geometry. The latter—and its dynamics—would emerge only in some type of macroscopic limit.

In fact, there exist various models, called “analogue models for gravity”, where a Lorentzian metric appears in a suitable regime, even though at the fundamental level this geometrical structure is absent [

10]. A well studied example is again the Bose–Einstein condensate, where it was shown that phonons,

in some regime, propagate in some (curved) Lorentzian geometry. In this sense, the Lorentzian geometry is emerging: it is not a description of the fundamental physics, it is only a valid description of the physics in a given regime, for some degrees of freedom.

Phonons are interpreted as (massless) matter in this model. When the condensation has occurred (that is the number N of atoms is large), the phonon can be considered as a perturbation around the condensate. In this sense, perturbations can be seen as coming from some large N limit and can encode merging degrees of freedom.

These analog models provide therefore some interesting examples where both matter and the metric do emerge. Unfortunately, there is a priori no known construction to obtain the Einstein equations, encoding the dynamics for the metric (albeit in a Bose–Einstein condensate it is possible to recover in some limit a Newtonian-like dynamics for the background [

11]).

Although still incomplete, these models provide some interesting relationships between geometrical structures and condensed matter systems illustrating the concept of emergence. There are also some striking relationships of Gravity with thermodynamics (

i.e., again some large

N limit). We can cite for example the well-known black hole thermodynamics or the derivation of the Einstein equations from a thermodynamical state equation by Jacobson [

12]. These results indicate that General Relativity could be an emergent theory, arising from some nontrivial large

N limit from a Quantum Gravity theory that does not have to be necessarily related to the notion of geometry.

The most developed Quantum Gravity theories at this stage are String theory and Loop/Spinfoam quantum gravity. The first considers roughly that the fundamental degrees of freedom describing gravity are encoded in a string. In this sense, this could be considered as an example of emergent gravity since the macrophysics (General Relativity) is very different from the microphysics (string physics). The Loop/Spinfoam approach consists of a direct (canonical or by path integral) quantization of General Relativity using a non-metric formulation. In this context, it is clearly assumed that the fundamental Quantum Gravity theory is about quantum geometry. (There are recent results corroborating this approach where discretized gravity is obtained after a semi-classical limit from some spin foam amplitude [

13]. Note however that there are also some proposals to obtain General Relativity as some large (thermodynamical/statistical)

N limit from spin foams encoded in some type of (Group) Field theory [

14].) We are however interested to know if the features describing time that we listed in the previous section are really fundamental,

i.e., associated to the fundamental Quantum Gravity theory. In both Quantum Gravity theories mentioned above, the signature is, in general, a background structure that is

not dynamical. Hence, following the above discussion, these are theories with a built-in time notion which at most can resolve the above mentioned paradoxes in GR by forbidding them rather that replacing or eliminating the notion of time. As previously said, our aim here is different in the sense that we shall show instead that signature and a diffeomorphisms invariant theory of gravitation can both be emergent concepts, not built in the fundamental theory.

4. Discussion: Dynamical Space-Time from a Timeless Non-Dynamical Space

We have showed, in a toy model, how the Lorentzian signature and a dynamical space-time can emerge from a flat non-dynamical Euclidean space, with no diffeomorphisms invariance built in. In this sense the toy-model provides an example where time (from the geometric perspective) is not fundamental, but simply an emerging feature. Accidentally this non-fundamental feature of time should automatically remove any issue about causality, as described in the first section of the essay, given that the very notion of causality would cease to be valid at high energies (which are always involved in the presence of chronological horizons [

4]).

The Lorentz and the diffeomorphisms symmetries are

emerging symmetries that is only approximate symmetries. Indeed when taking into account the third order terms in (

7), these symmetries are simply broken. This is quite natural since the model (

4) has nothing to do with either of these symmetries.

Since we have a concrete model, one can ask if the observers living in such emergent space-time could foresee that time is actually not fundamental. There are in fact various possible ways, even though this could be quite difficult experimentally. For example, the first obvious way is to be able to measure a Lorentz symmetry breaking contribution in high-energy (in our case in the form of a non-dynamical ether field). There could be also a possible window in the strong gravitating regime. Indeed our derivation obviously holds for small perturbations , and hence small , implying that in our framework one would predict strong deviations from the weak field limit of the theory whenever the gravitational field becomes very large. It would be interesting to see how these deviations actually do appear.

We want to emphasize again that the toy-model describes Nordström gravity, which is clearly non-physical since there is no bending of light. It would be extremely interesting to be able to derive in a similar way General Relativity, even though this seems to be a very difficult task (for example, it would probably require a mechanism that selects only a background signature and not the whole Minkowski metric as in our case, given that only the former is allowed to be non-dynamical in GR). One would in this case aim to obtain the emergence of a theory characterized by spin-2 gravitons (while in Nordström theory the graviton is just a scalar). This could open a door to a possible conflict with the so called Weinberg–Witten theorem [

20]. However, there are many ways in which such a theorem can be evaded (see e.g., [

21]) and in particular one may guess that analogue models inspired mechanisms like the one discussed here will generically lead to Lagrangian which shows Lorentz and diffeomorphisms invariance only as approximate symmetries for the lowest order in the perturbative expansion (while the Weinberg–Witten theorem assumes exact Lorentz invariance).

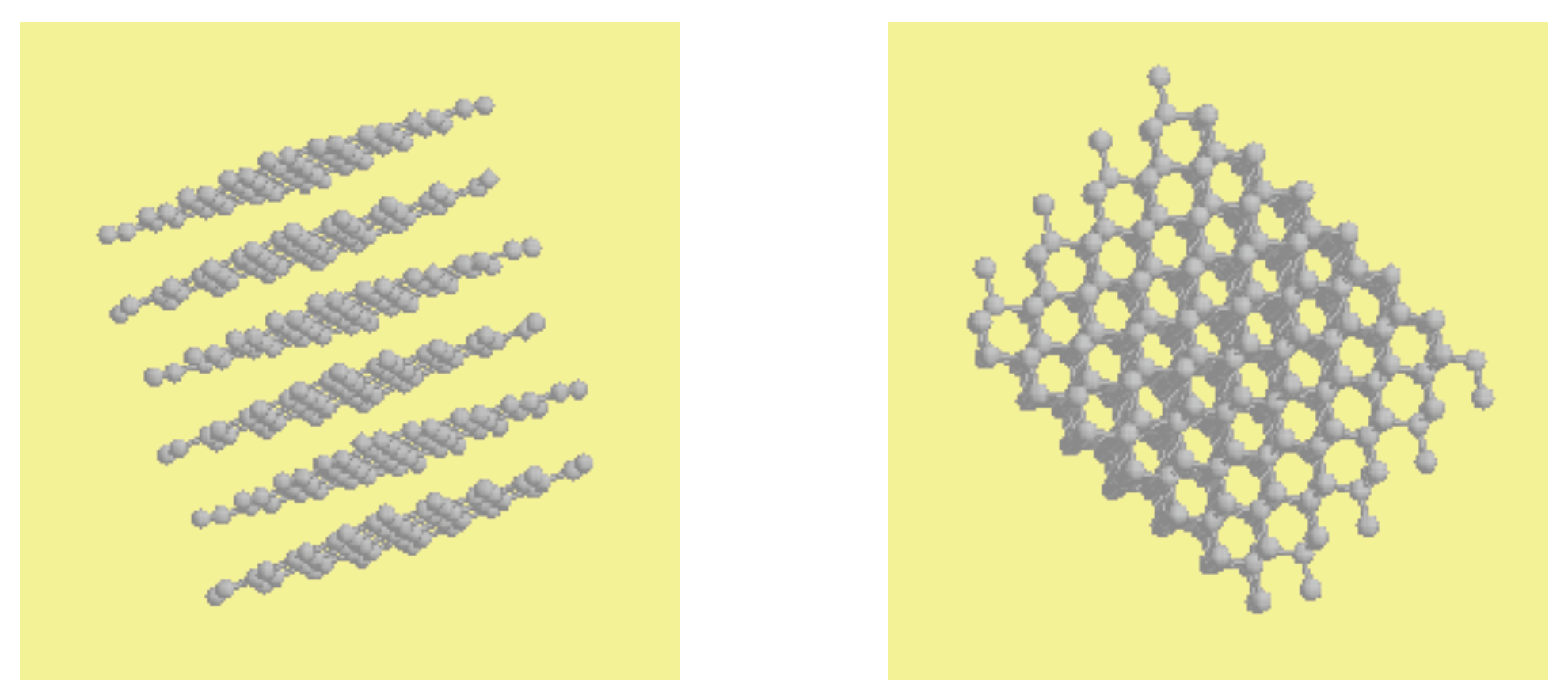

The emergence of time in our toy-model is also very much dependent on the choice of the solution . In fact the specific choice of might even seem a bit contrived. The fact that we are unable to choose might be due to the that other ingredients are needed to fully understand how a time-like direction can emerge in a natural way out of an Euclidean system. This might be due to the fundamental theory, as it has been pictorially described by the diamond/graphite example, or due to some other criterion, like a minimization of another state functional which we presently do not know. The toy-model would clearly gain in strength if one is able to show that the solution is preferred for some reason. In this sense one could predict the apparition of time.

We are clearly aware of these two drawbacks (i.e., Nordström is not General Relativity, the choice of ), however we think that they should not hide our main point: It is possible to construct a toy-model and to identify at least one solution such that a dynamical space-time together with matter do emerge from a timeless non-dynamical space. We have therefore provided an example where time and gravity are not fundamental but only emergent.