Optimization of Monitoring Node Layout in Desert–Gobi–Wasteland Regions Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Multidimensional environmental modeling. A multidimensional simulation environment model is constructed for desert–Gobi–wasteland regions by integrating terrain, solar radiation, and wind-speed information. This model enables quantitative description and simulation of meteorological monitoring network layout problems.

- (2)

- Environment-aware reinforcement learning algorithms. To address the dimensionality and convergence challenges of traditional DRL in high-dimensional layout tasks, the EA-PPO algorithm is proposed, significantly enhancing policy learning efficiency and stability. Building upon EA-PPO, the GLOAE is further developed to achieve adaptive node deployment through a collaborative, global-benefit-oriented multi-agent learning mechanism.

- (3)

- Comprehensive experimental validation. Extensive simulation experiments demonstrate that EA-PPO and GLOAE outperform conventional methods in terms of layout quality, convergence speed, global utility, and adaptability to dynamic environmental changes. The results indicate that the proposed methods exhibit strong practicality and generalization potential in complex desert–Gobi–wasteland environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. Mathematical Optimization Methods

2.2. Intelligent Optimization Methods

2.3. Deep Reinforcement Learning–Driven Intelligent Layout Methods

3. Simulation Environment Construction and Problem Modeling

3.1. Simulation Modeling of the Desert–Gobi–Wasteland Regions

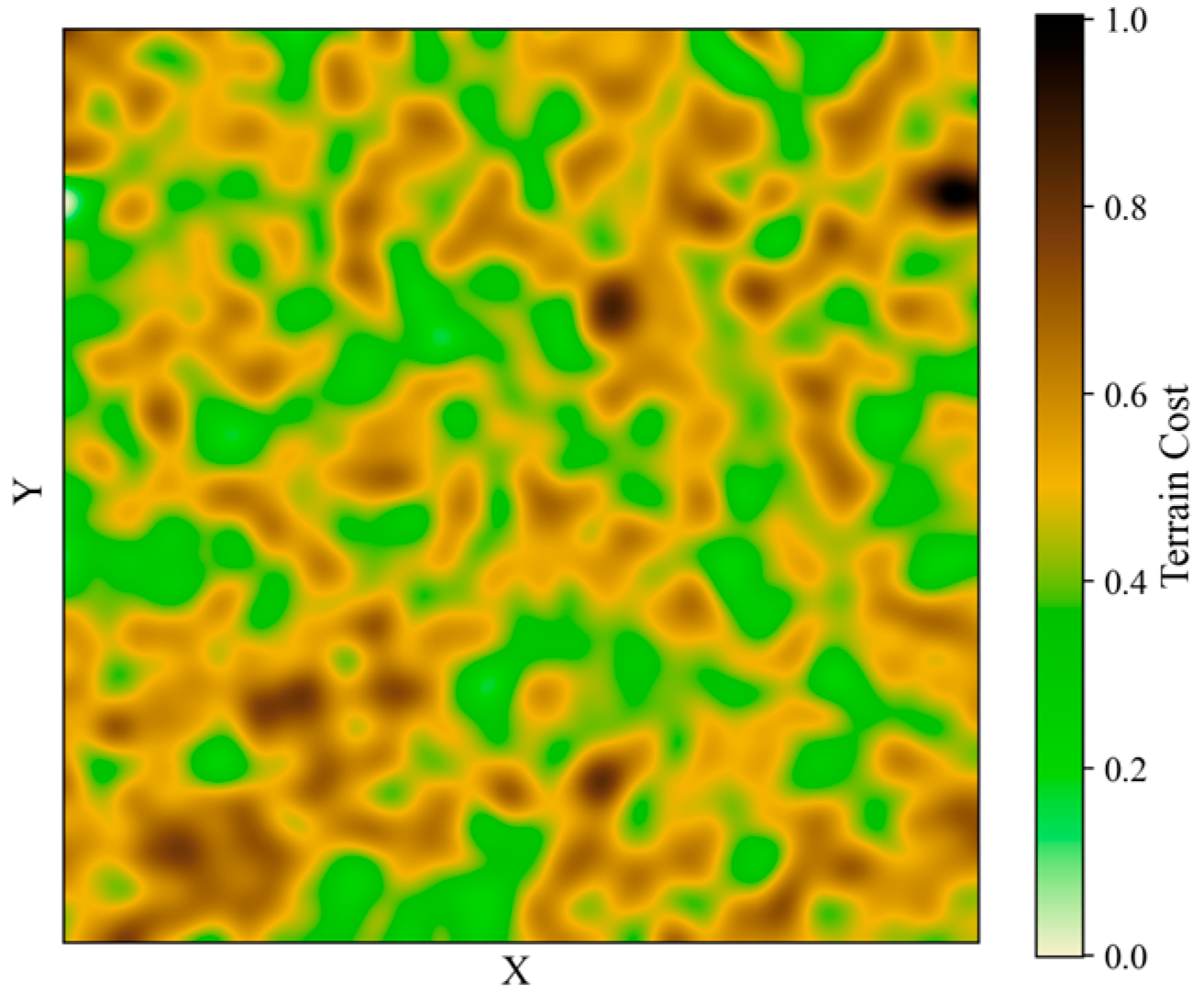

3.1.1. Terrain Cost Map

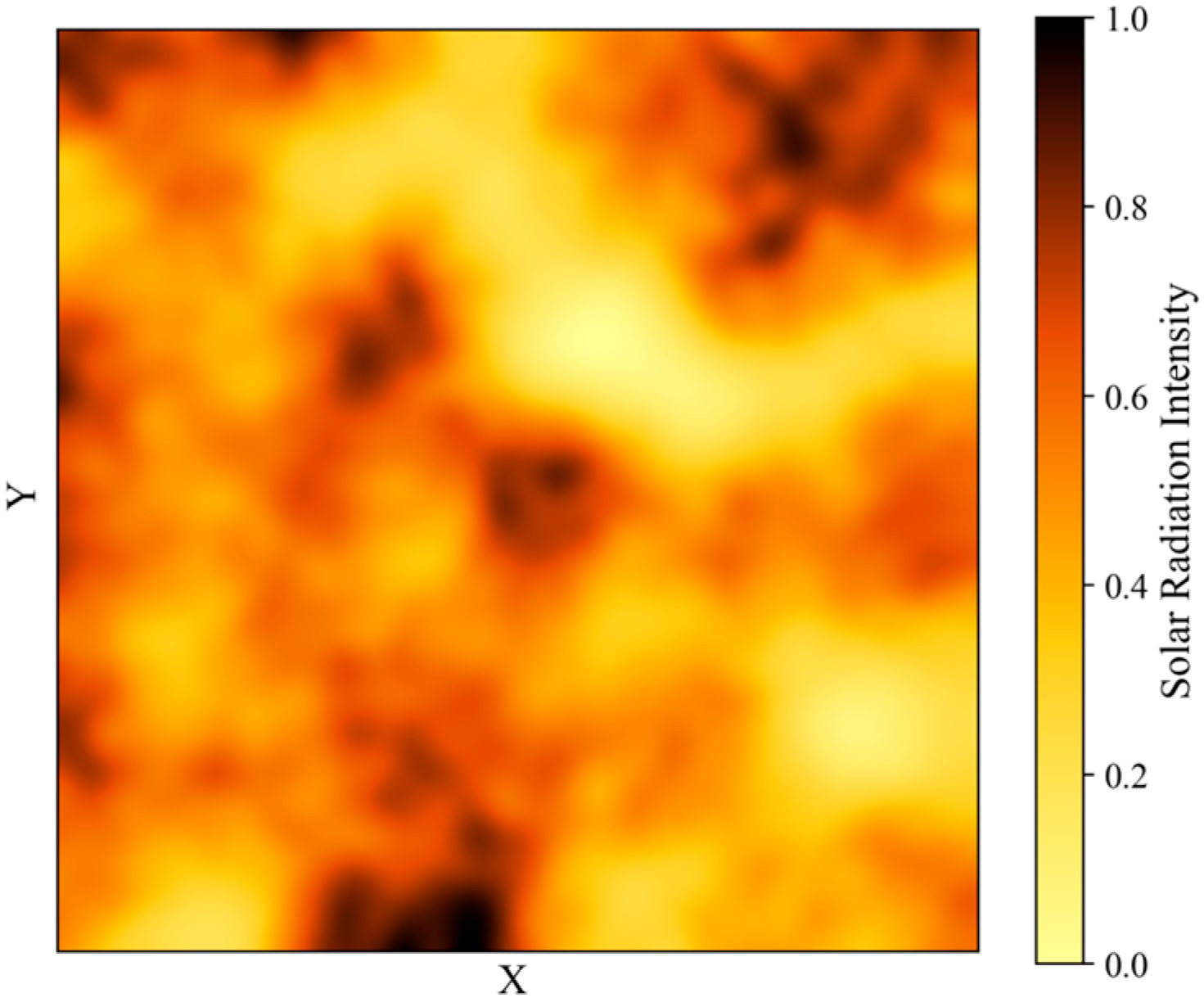

3.1.2. Solar Radiation Map

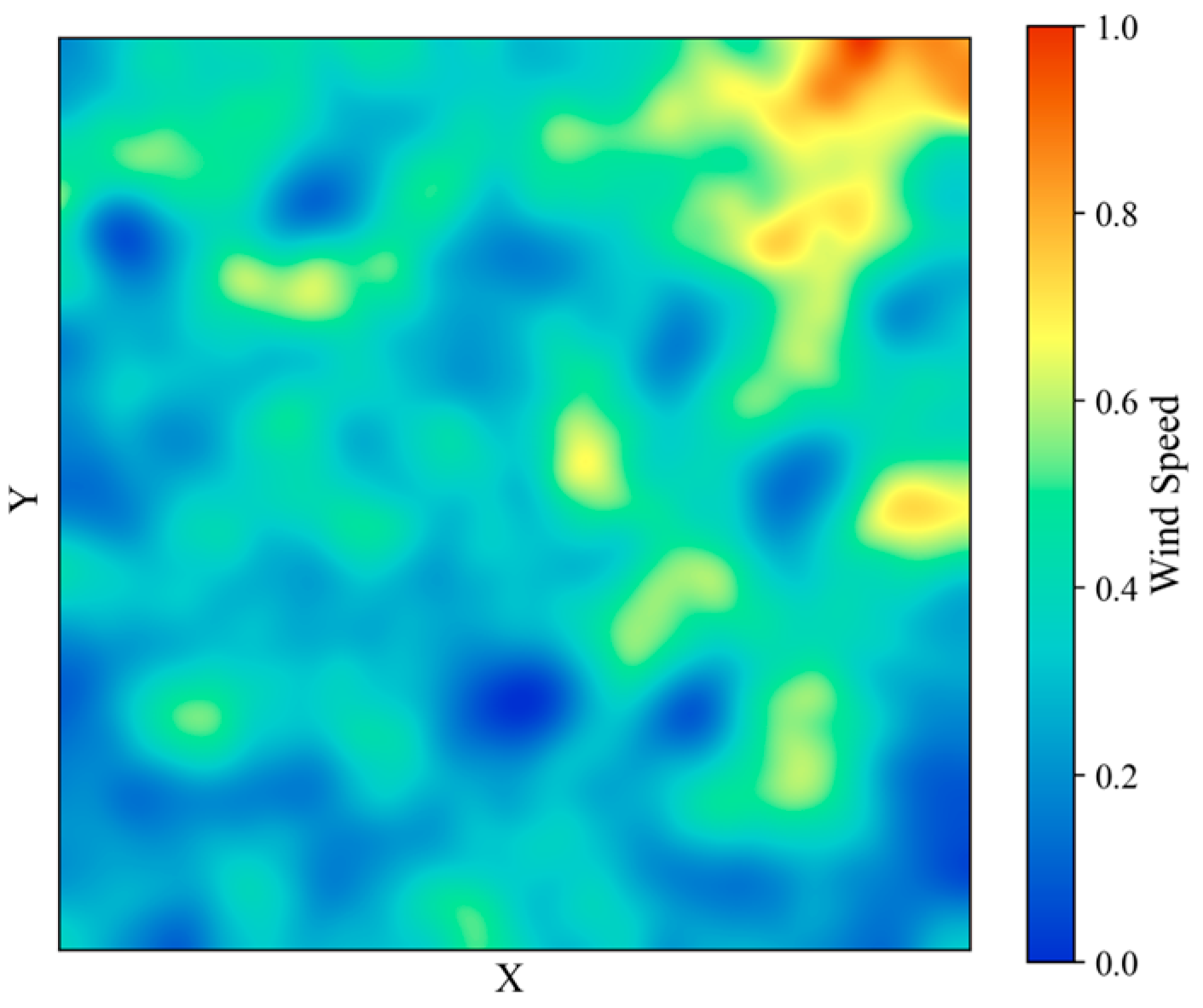

3.1.3. Wind Speed Intensity Map

3.2. Simulation Region and Node Sensing Model

3.3. Problem Description

4. Algorithm Design and Implementation

4.1. Overview of the PPO Algorithm

4.2. Environment-Aware Layout Optimization Algorithm: EA-PPO

4.2.1. MDP Modeling

4.2.2. EA-PPO Algorithm Description

| Algorithm 1. EA-PPO | |

| Input: Terrain cost map, solar radiation map, and wind-speed map of the desert–Gobi–wasteland regions; maximum training iterations; total time steps T Output: Trained policy network Initialization: Initialize the policy network π and value network V corresponding to the agent; initialize replay buffer D | |

| 1: | do |

| 2: | to T |

| 3: | |

| 4: | |

| 5: | |

| 6: | |

| 7: | End for |

| 8: | Update policy network π and value network V using data from replay buffer D |

| 9: | End while |

| 10: | |

4.3. Global Layout Optimization Algorithm Based on EA-PPO (GLOAE)

| Algorithm 2. GLOAE | |

| Input: Terrain cost map, solar radiation map, and wind-speed map of the desert–Gobi–wasteland regions; EA-PPO algorithm; maximum training iterations; total runtime T Output: Final positions of all monitoring nodes Initialization: Initialize the initial positions of all monitoring nodes; initialize the policy network π and value network V for each agent; initialize replay buffer D | |

| 1: | do |

| 2: | |

| 3: | |

| 4: | Perform decision-making for each agent individually using EA-PPO |

| 5: | Update the positions of all agents synchronously |

| 6: | Compute the reward of each agent based on the global utility function evaluated from the updated node layout |

| 7: | into replay buffer D |

| 8: | End for |

| 9: | End for |

| 10: | of each agent using EA-PPO |

| 11: | End while |

| 12: | return the final node layout map |

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

5.1. Simulation Environment and Parameters

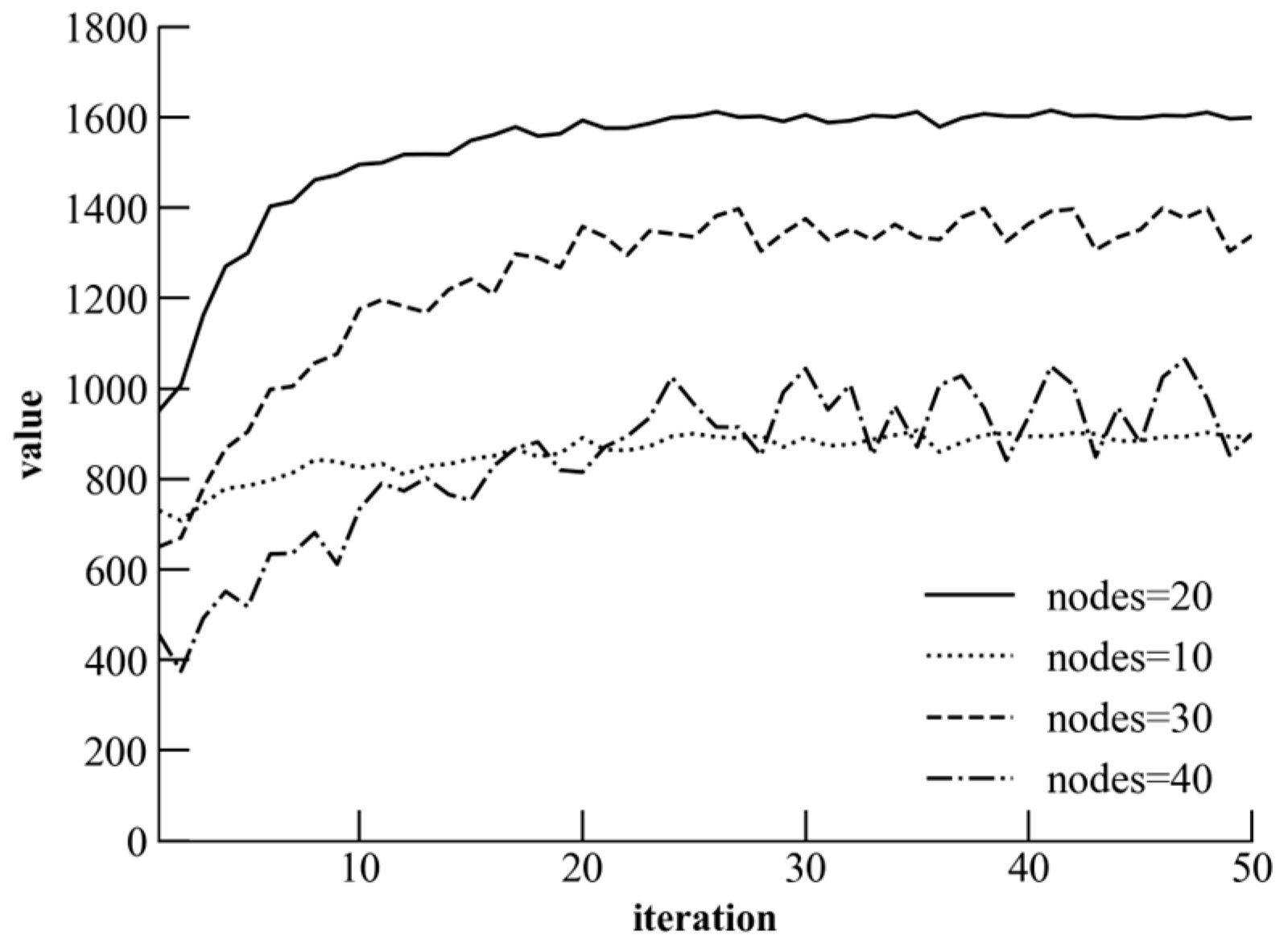

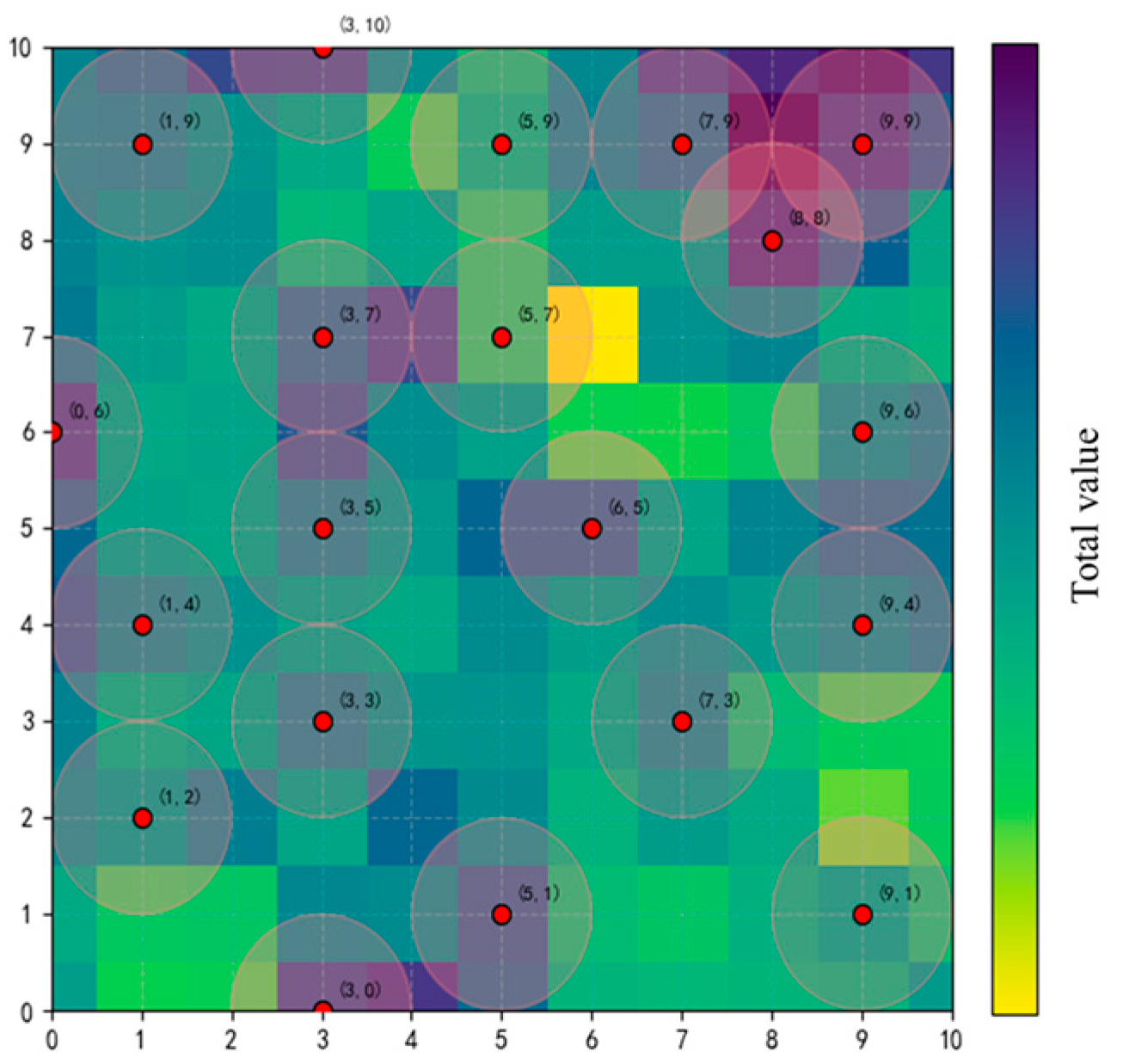

5.2. Determination of the Number of Nodes and Result Visualization

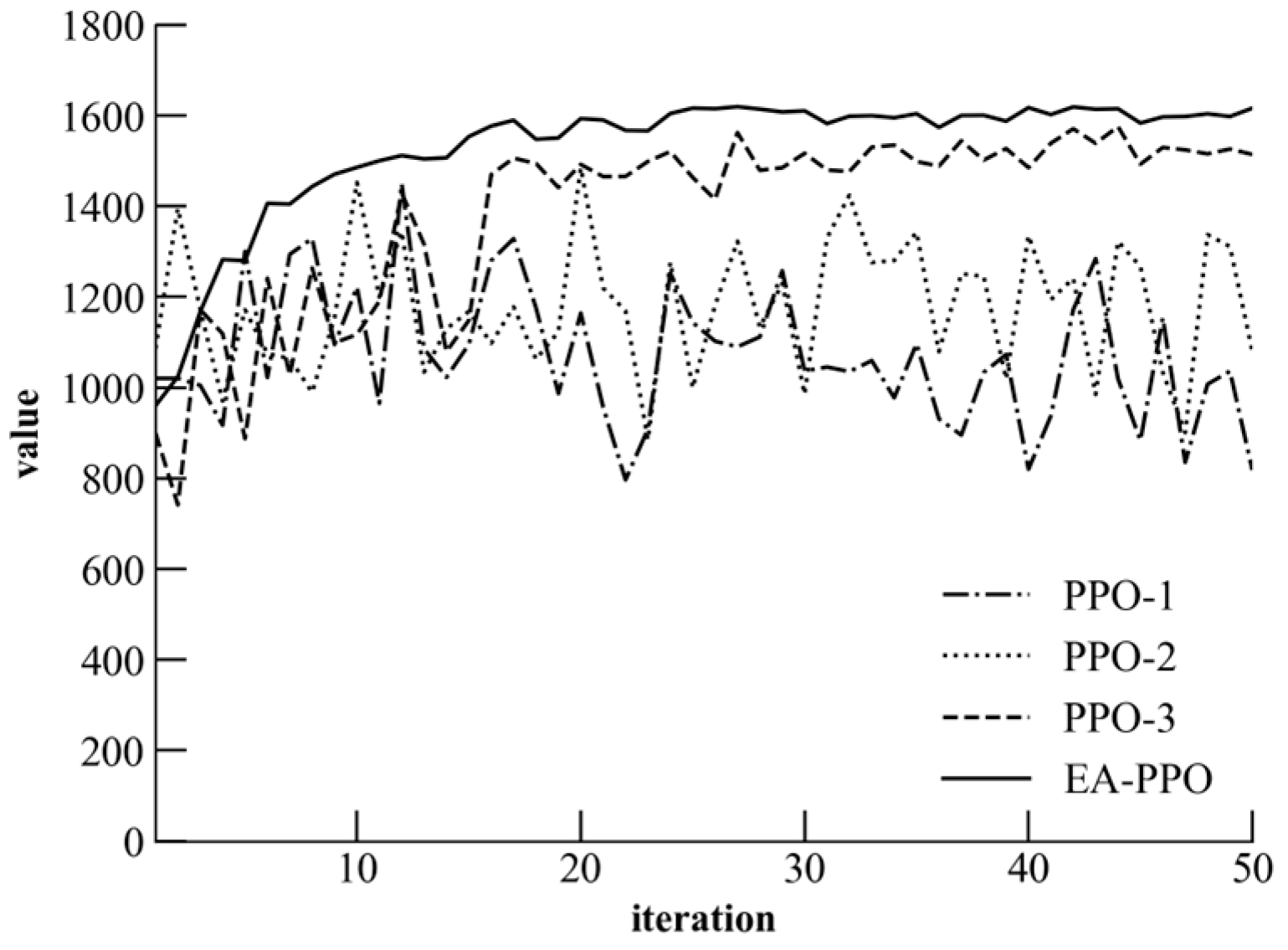

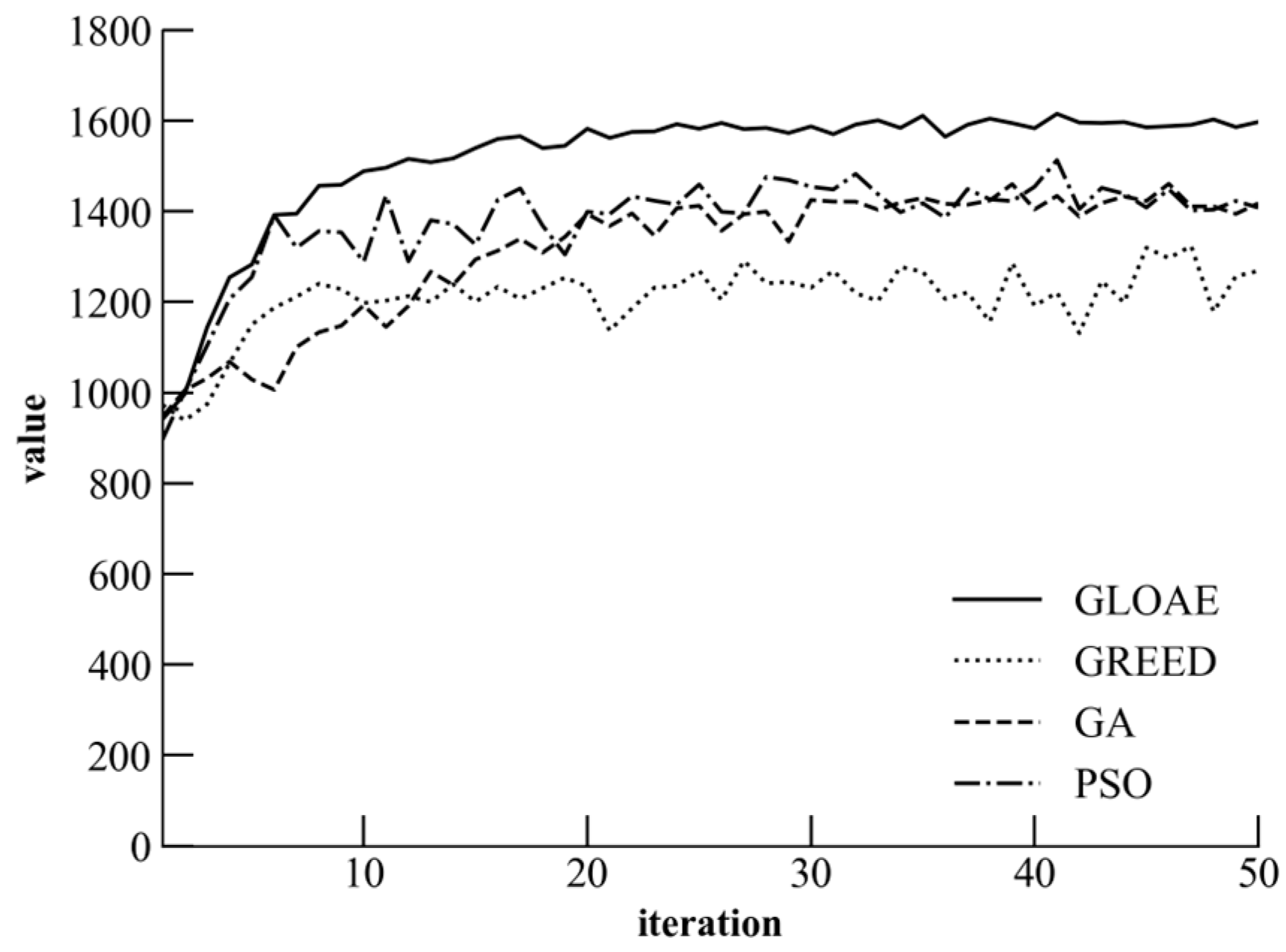

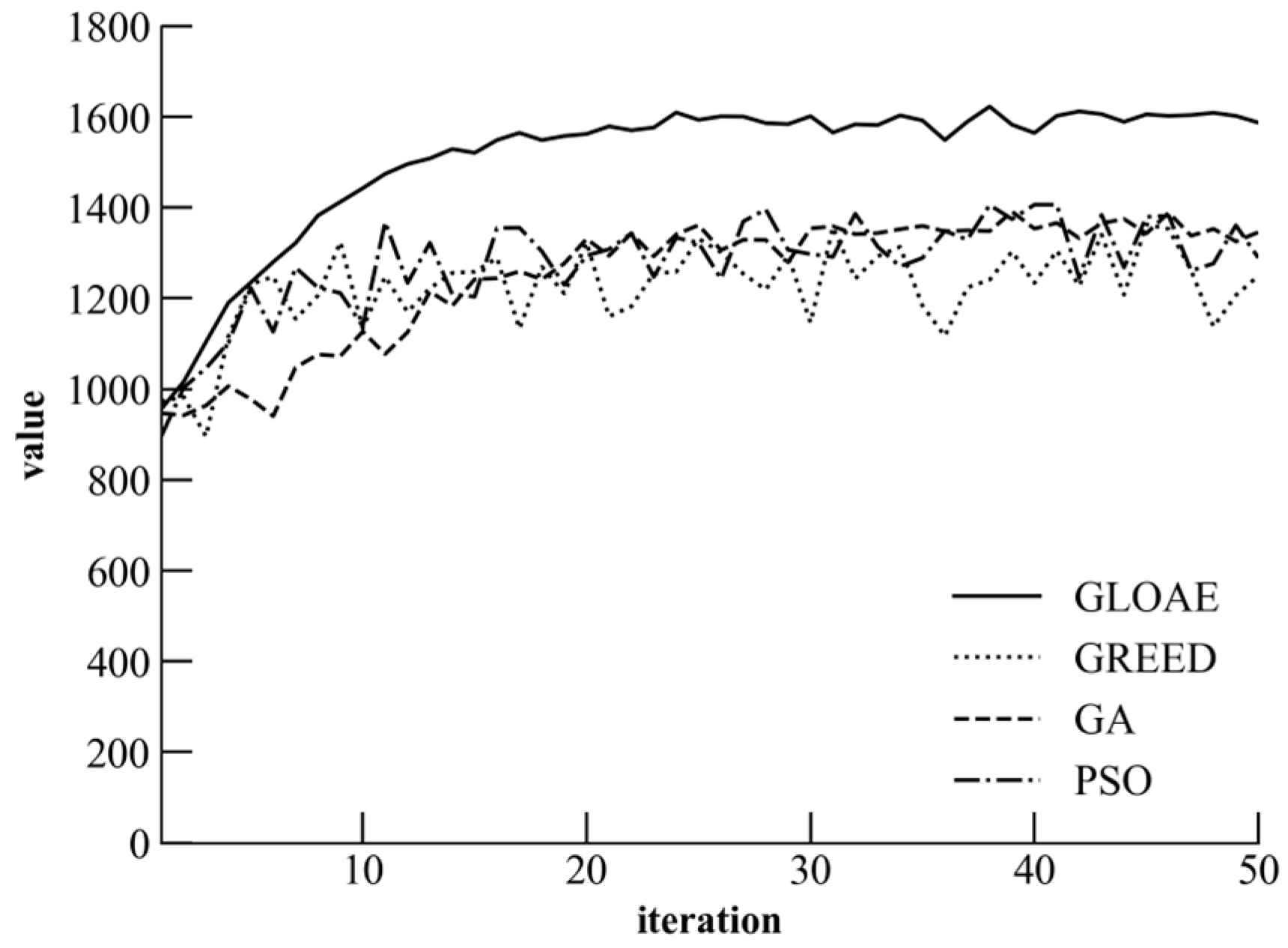

5.3. Convergence Characteristics and Performance Analysis of the Algorithm

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, S. How to Accelerate the Construction of “Shagehuang” New Energy Bases. People’s Daily, 6 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, D. Qinghai Assesses the Power Generation Potential of the “Shagehuang” Region. People’s Daily, 13 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Sun, J.; Ma, R.; Wang, W. Day-Ahead Low-Carbon Dispatch Strategy of Power Systems for New Energy Consumption in “Shagehuang” Regions. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Xie, K.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, D. Bi-objective layout optimization for multiple wind farms considering sequential fluctuation of wind power using uniform design. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 8, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Li, H. A Chaotic Local Search-Based Particle Swarm Optimizer for Large-Scale Complex Wind Farm Layout Optimization. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fang, X.; Niyato, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. DRL Optimization Trajectory Generation via Wireless Network Intent-Guided Diffusion Models for Optimizing Resource Allocation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.14481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Li, F.; He, L. DRL-based joint resource allocation and device orchestration for hierarchical federated learning in NOMA-enabled industrial IoT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 7468–7479. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Geng, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X. DRL-Based Resource Allocation and Trajectory Planning for NOMA-Enabled Multi-UAV Collaborative Caching 6G Network. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 8750–8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Bai, Y.; Yue, X.; Wang, R.; Song, Q. A wind speed forcasting model based on rime optimization based VMD and multi-headed self-attention-LSTM. Energy 2024, 294, 130726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Lin, Y. Collaborative Layout Optimization for Ship Pipes Based on Spatial Vector Coding Technique. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 116762–116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Cheng, Y. Influence of Atmospheric Stability on Wind Farm Layout Optimization Based on an Improved Gaussian Wake Model. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 211, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Gao, S. Triple-Layered Chaotic Differential Evolution Algorithm for Layout Optimization of Offshore Wave Energy Converters. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 239, 122439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kou, X.; Song, Z.; Fan, Y.; Usman, M.; Jagota, V. Research on Logistics Management Layout Optimization and Real-Time Application Based on Nonlinear Programming. Nonlinear Eng. 2021, 10, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, B.; Su, J. Facilities Layout Design Optimization of Production Workshop Based on the Improved PSO Algorithm. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 112025–112037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daqaq, F.; Ellaia, R.; Ouassaid, M.; Zawbaa, H.M.; Kamel, S. Enhanced Chaotic Manta Ray Foraging Algorithm for Function Optimization and Optimal Wind Farm Layout Problem. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 78345–78369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.; Jiang, K.; Xing, J.; Jiang, T. BPSO and staggered triangle layout optimization for wideband RCS reduction of pixelate checkerboard metasurface. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2022, 70, 3406–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.F.D.; Lazzarin, T.B.; Schmitz, L.; Panisson, A.R. Genetic Algorithm-Based Optimization Framework for Offshore Wind Farm Layout Design. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 170081–170094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemim, L.S.; Nicolle, C.S.; Kleina, M. Layout optimization methods and tools: A systematic literature review. Gepros Gestão Produção Operações Sist. 2021, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, M.; Wu, B. Application of Deep Reinforcement Learning in Heterogeneous Sensor Networks. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J. Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning for Multi-Objective Integrated Circuit Physical Layout Optimization with Congestion-Aware Reward Shaping. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 162533–162551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Kan, M.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Cao, B. An Adaptive Coverage Method for Dynamic Wireless Sensor Network Deployment Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpa, G.; Babu, R.A.; Subashree, S.; Senthilkumar, S. Optimizing Coverage in Wireless Sensor Networks Using Deep Reinforcement Learning with Graph Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhuri, R.; Barma, M.K.D. Node position estimation based on optimal clustering and detection of coverage hole in wireless sensor networks using hybrid deep reinforcement learning: R. Chowdhuri, MKD Barma. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 20845–20877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; He, Q.; Huang, J.; Mamtimin, A.; Yang, X.; Huo, W.; Zhou, C.; Liu, X.; Wei, W.; Cui, C.; et al. Desert Environment and Climate Observation Network over the Taklimakan Desert. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 102, E1172–E1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Velu, A.; Vinitsky, E.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Bayen, A.; Wu, Y. The Surprising Effectiveness of PPO in Cooperative Multi-Agent Games. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24611–24624. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, C.; Xiong, K.; Chen, W.; Gao, B.; Fan, P.; Letaief, K.B. Sum-Rate Maximization in STAR-RIS-Assisted RSMA Networks: A PPO-Based Algorithm. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 5667–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Wang, L. Robust Topology Generation of Internet of Things Based on PPO Algorithm Using Discrete Action Space. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 5406–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, M.; Liu, X.; Wen, X.; Wang, N.; Long, K. PPO-Based PDACB Traffic Control Scheme for Massive IoV Communications. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2023, 24, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, C.A. An Updated Survey of GA-Based Multiobjective Optimization Techniques. ACM Comput. Surv. 2000, 32, 109–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A. Greedy Algorithms: A Review and Open Problems. J. Inequal. Appl. 2025, 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Chen, K.; Qu, Q. PPSwarm: Multi-UAV Path Planning Based on Hybrid PSO in Complex Scenarios. Drones 2024, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| w1 | 0.15 |

| w2 | 0.25 |

| w3 | 0.2 |

| w4 | 0.4 |

| epochs | 50 |

| T | 100 |

| optimizer | Adam |

| learning rate | 0.01 |

| discount factor | 0.98 |

| clipping value | 0.2 |

| batch size | 2000 |

| Algorithm | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| GA | Population size | 50 |

| Crossover rate | 0.8 | |

| Mutation rate | 0.05 | |

| PSO | Swarm size | 50 |

| Cognitive coefficient | 2.0 | |

| Social coefficient | 2.0 | |

| Inertia weight | 0.7 | |

| Greedy | Strategy | Deterministic |

| Algorithm | Convergence Mean (Before Perturbation) | Standard Deviation | Convergence Mean (After Perturbation) | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLOAE | 1592.4 | 14.8 | 1588.1 | 18.1 |

| GREED | 1238.6 | 58.8 | 1261.3 | 70.2 |

| GA | 1420.9 | 16.9 | 1353.9 | 20.3 |

| PSO | 1438.2 | 36.2 | 1332.5 | 55.6 |

| Algorithm | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| GLOAE | 1587.3 | 19.0 |

| GREED | 1245.6 | 123.9 |

| GA | 1358.7 | 41.8 |

| PSO | 1368.2 | 48.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, Z.; Lv, Q.; Xie, Z.; Li, R.; Huo, J. Optimization of Monitoring Node Layout in Desert–Gobi–Wasteland Regions Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Symmetry 2026, 18, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020237

Han Z, Lv Q, Xie Z, Li R, Huo J. Optimization of Monitoring Node Layout in Desert–Gobi–Wasteland Regions Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Symmetry. 2026; 18(2):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020237

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Zifen, Qingquan Lv, Zhihua Xie, Runxiang Li, and Jiuyuan Huo. 2026. "Optimization of Monitoring Node Layout in Desert–Gobi–Wasteland Regions Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning" Symmetry 18, no. 2: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020237

APA StyleHan, Z., Lv, Q., Xie, Z., Li, R., & Huo, J. (2026). Optimization of Monitoring Node Layout in Desert–Gobi–Wasteland Regions Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Symmetry, 18(2), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020237