A Symmetry-Coordinated Approach for Ionospheric Modeling: The SH-RBF Hybrid Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Ionospheric Modeling Methods

2.1.1. Ionospheric Delay Extraction

2.1.2. Polynomial Models

2.1.3. Spherical Harmonic Function Model

2.1.4. SH-RBF Model

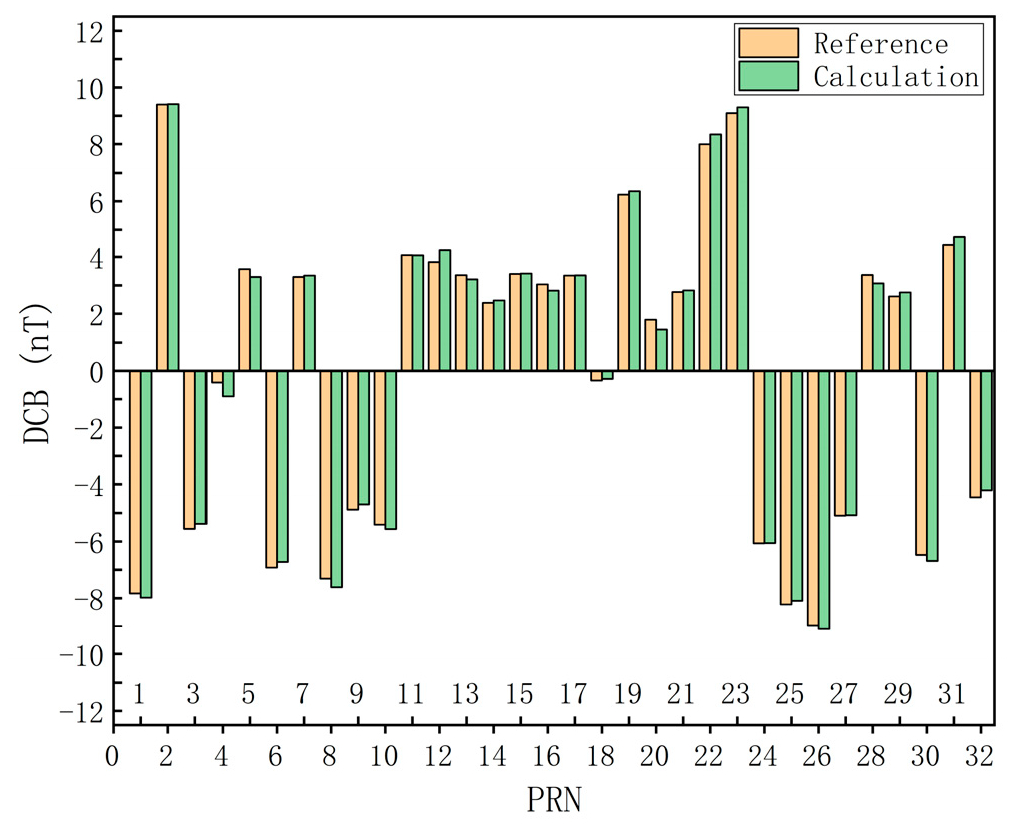

2.1.5. Calculate Differential Code Bias

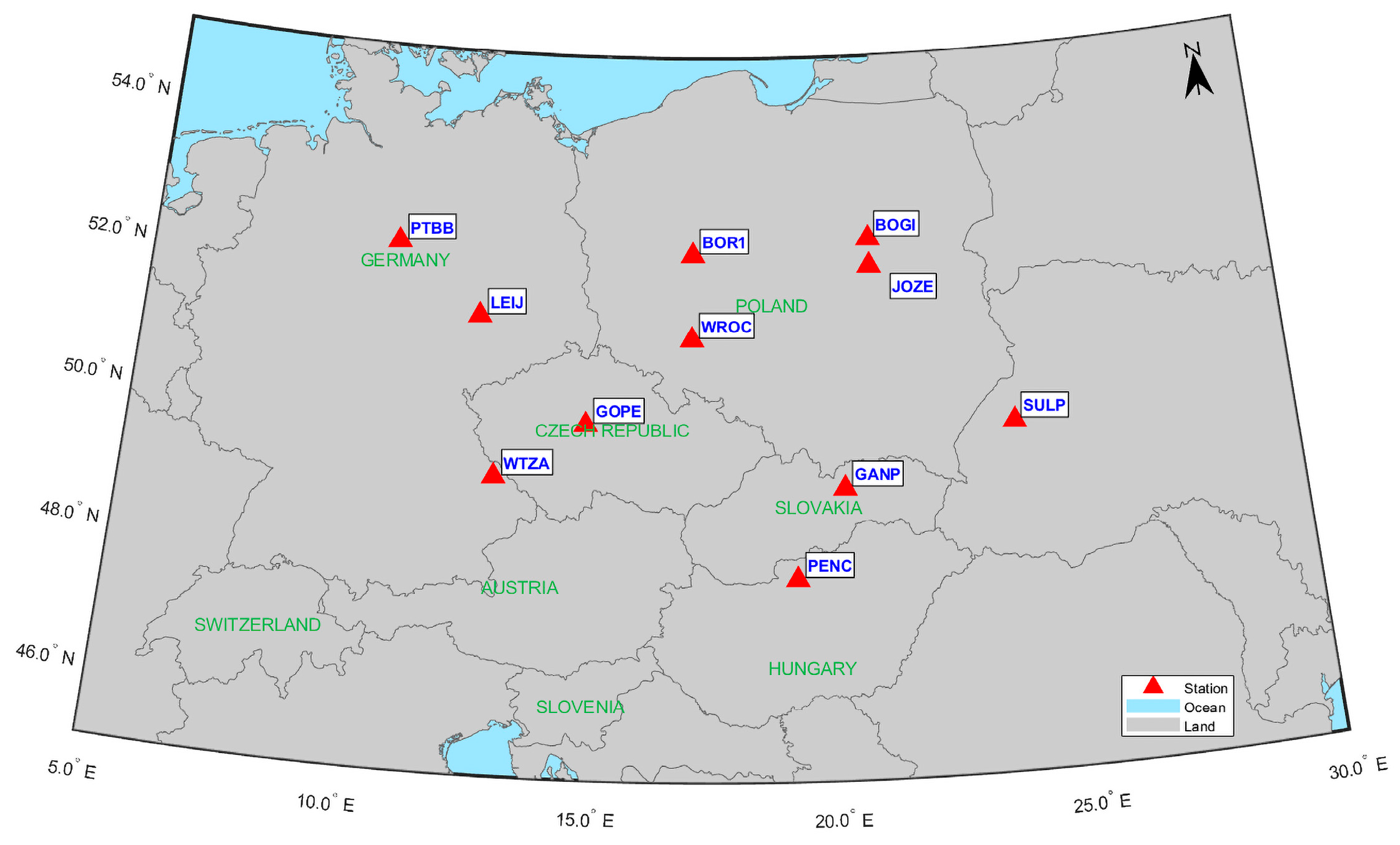

2.2. Data

3. Results

3.1. Modeling Results

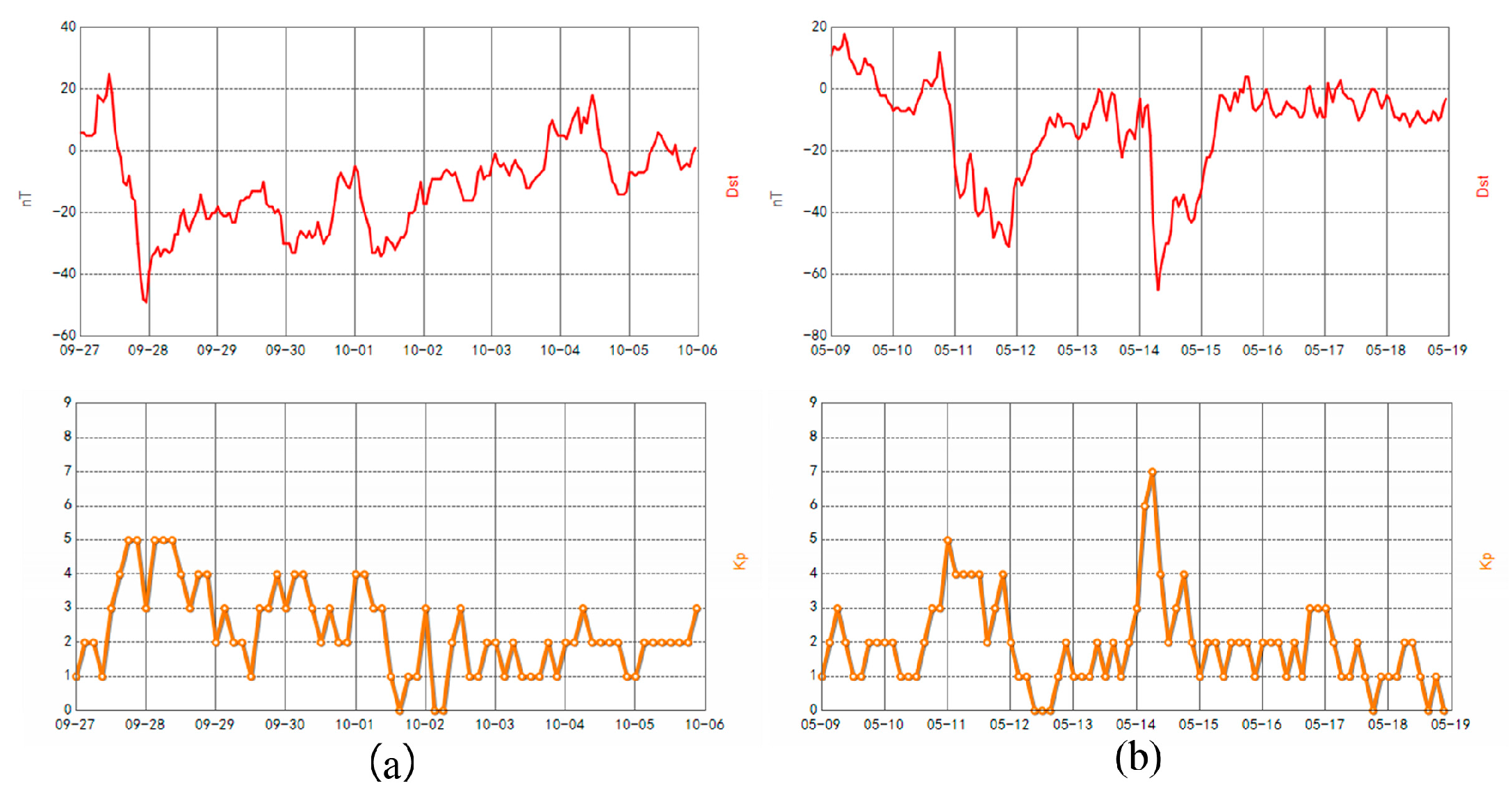

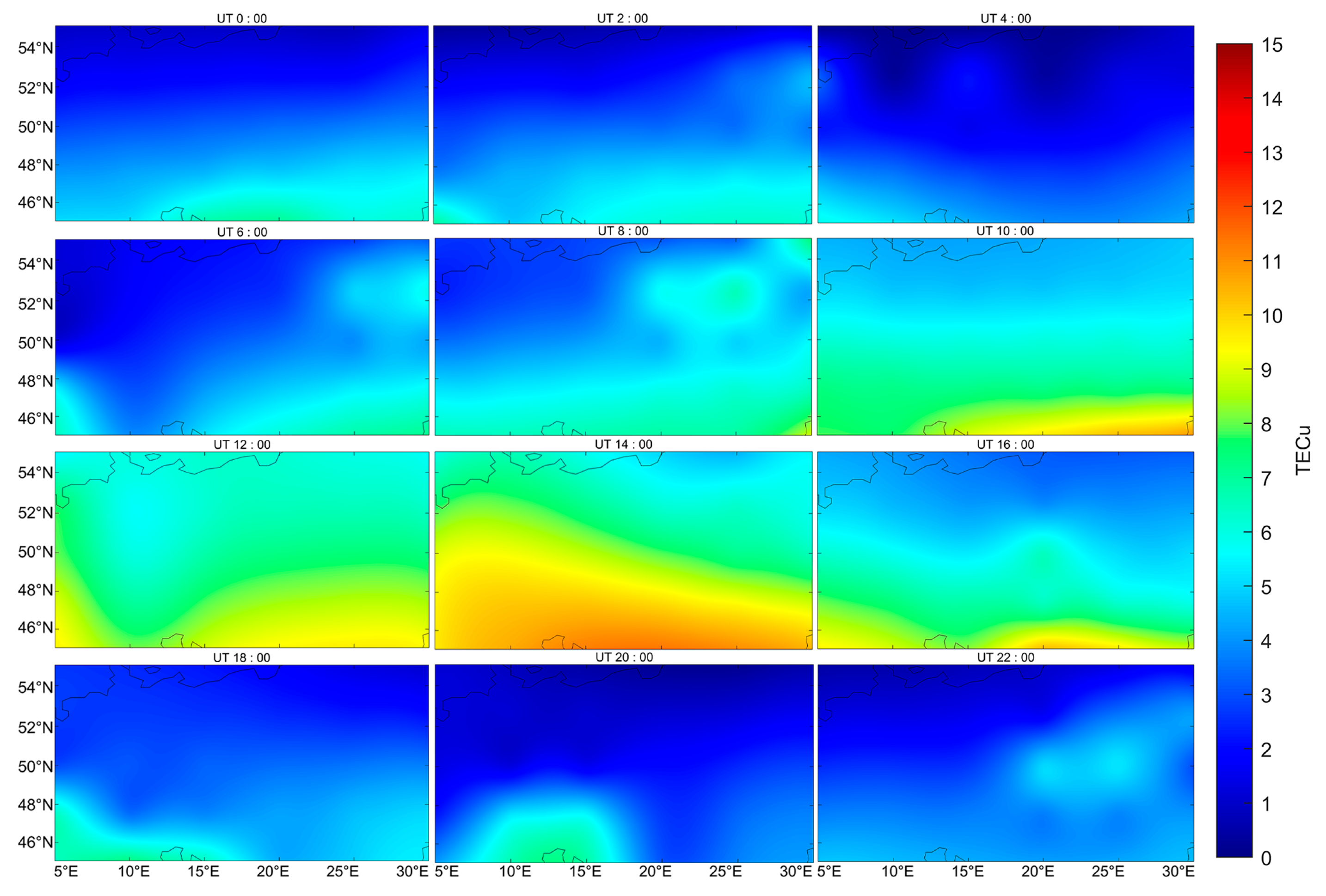

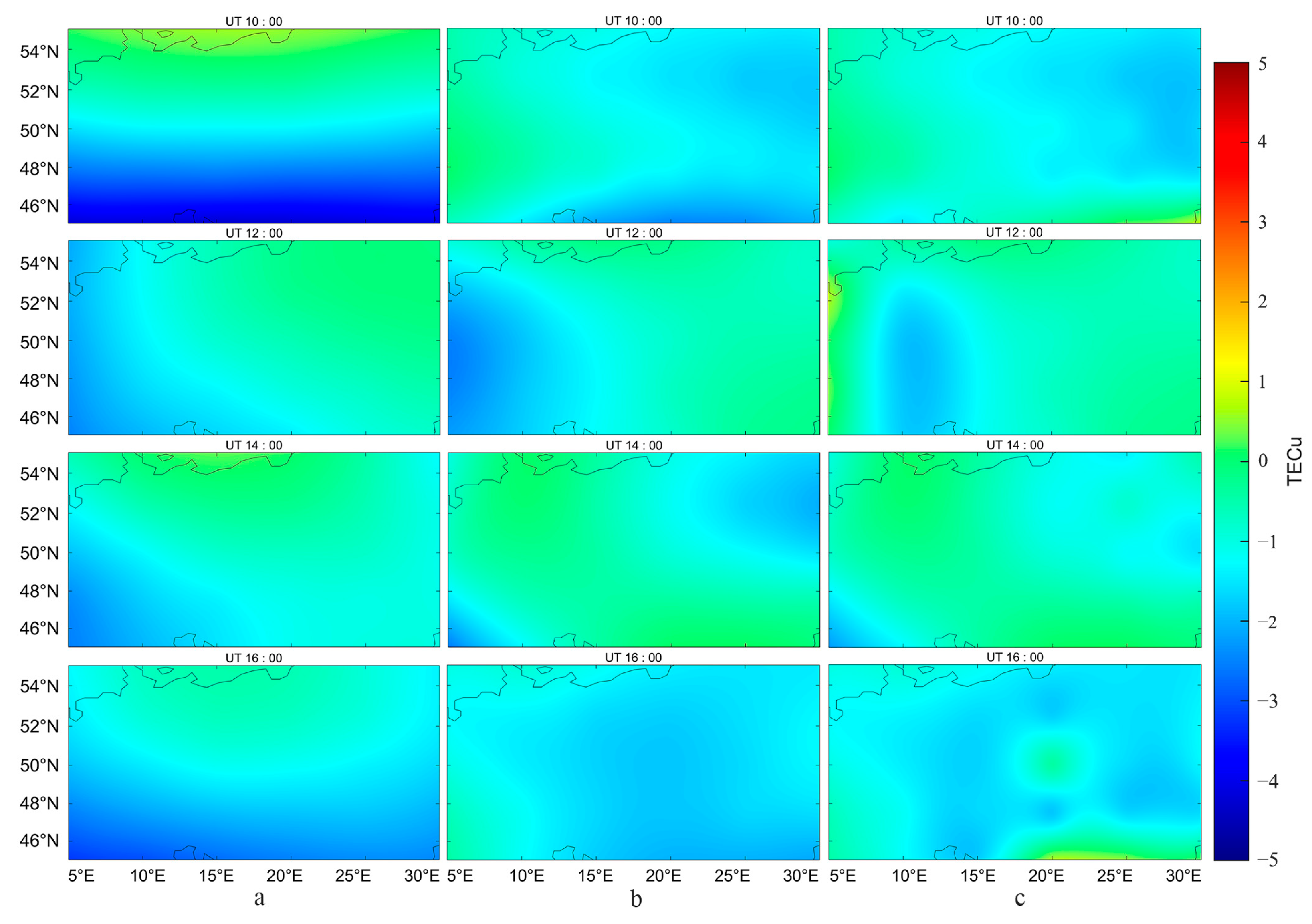

3.1.1. Geomagnetically Quiet Periods

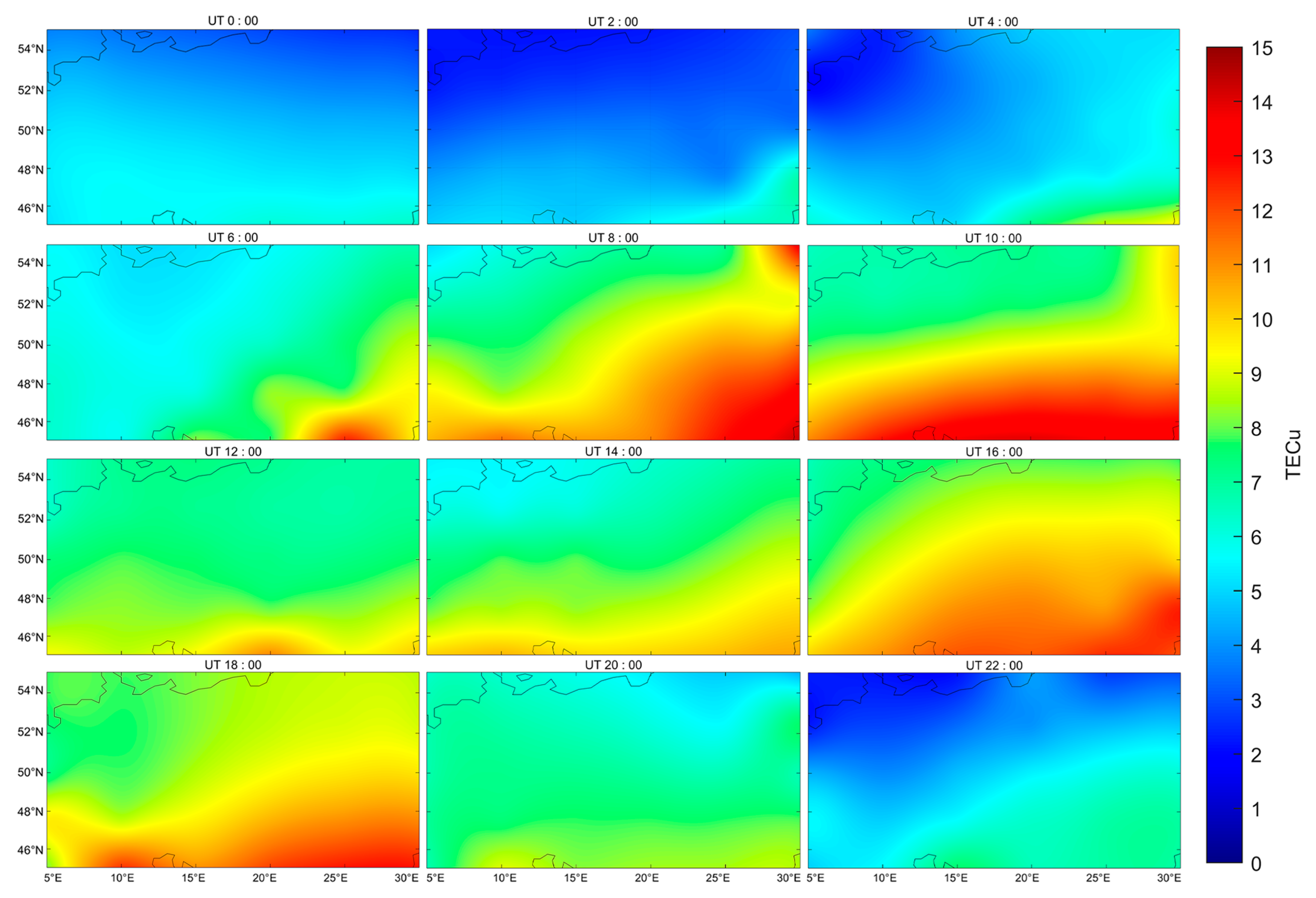

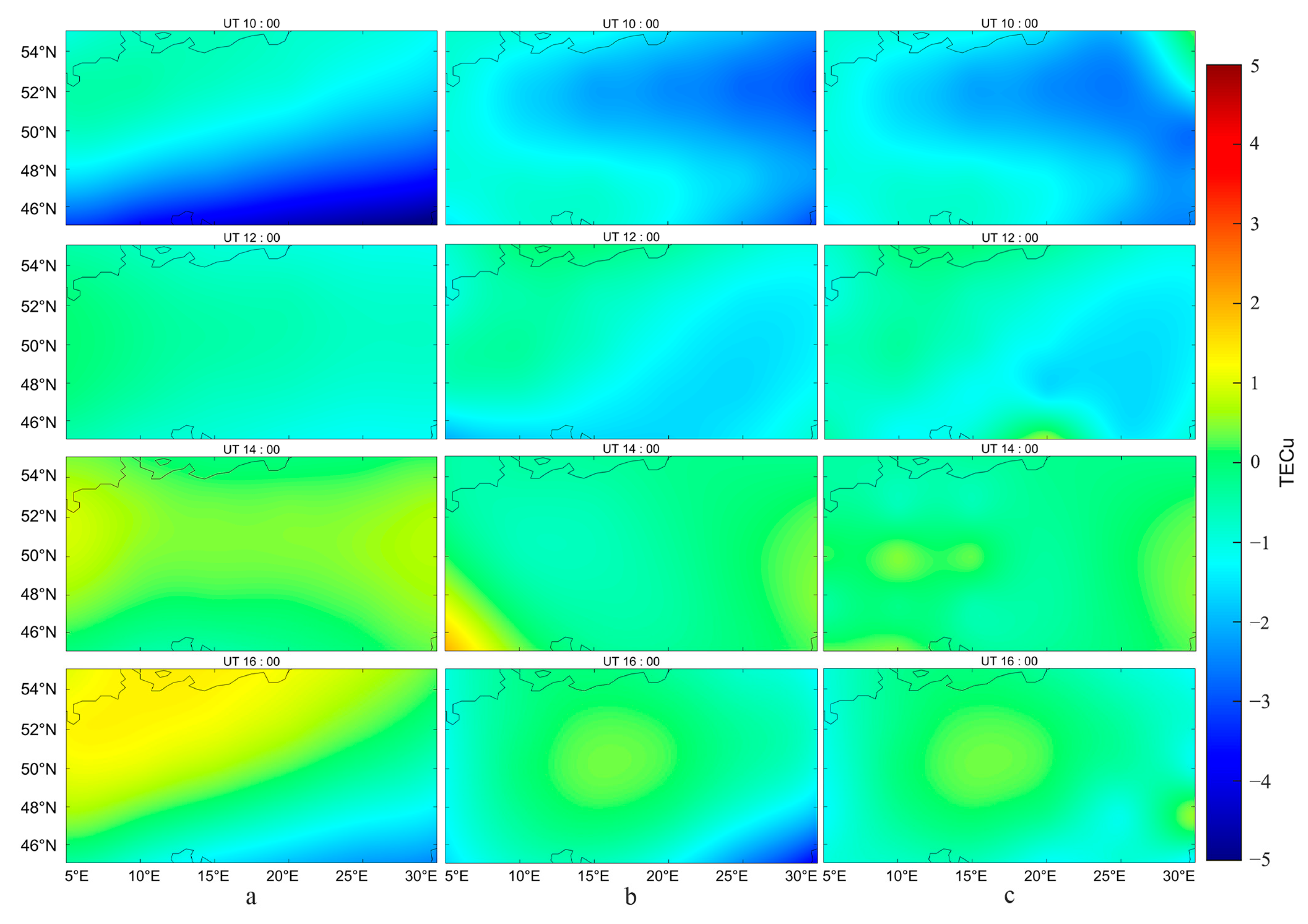

3.1.2. Geomagnetically Active Periods

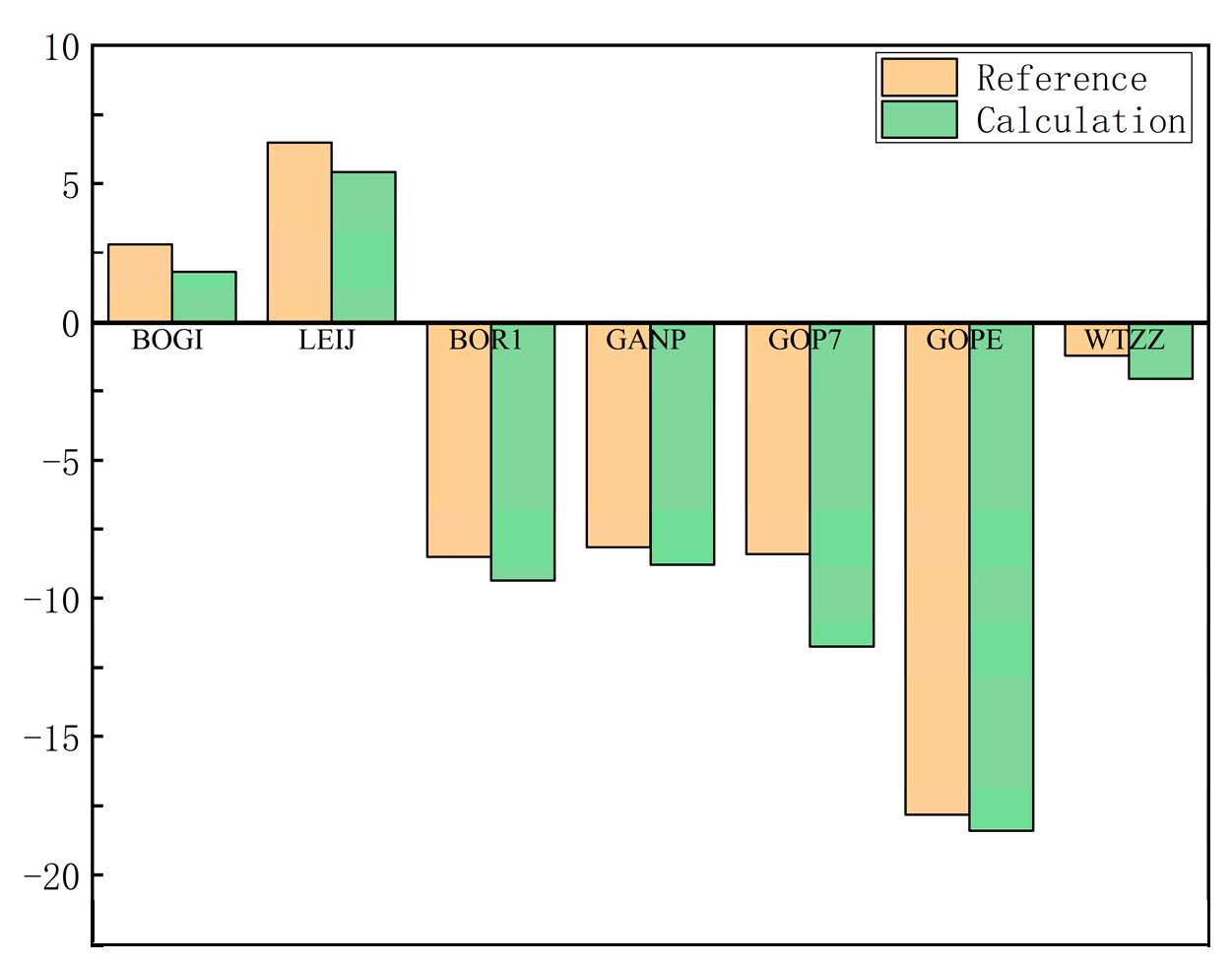

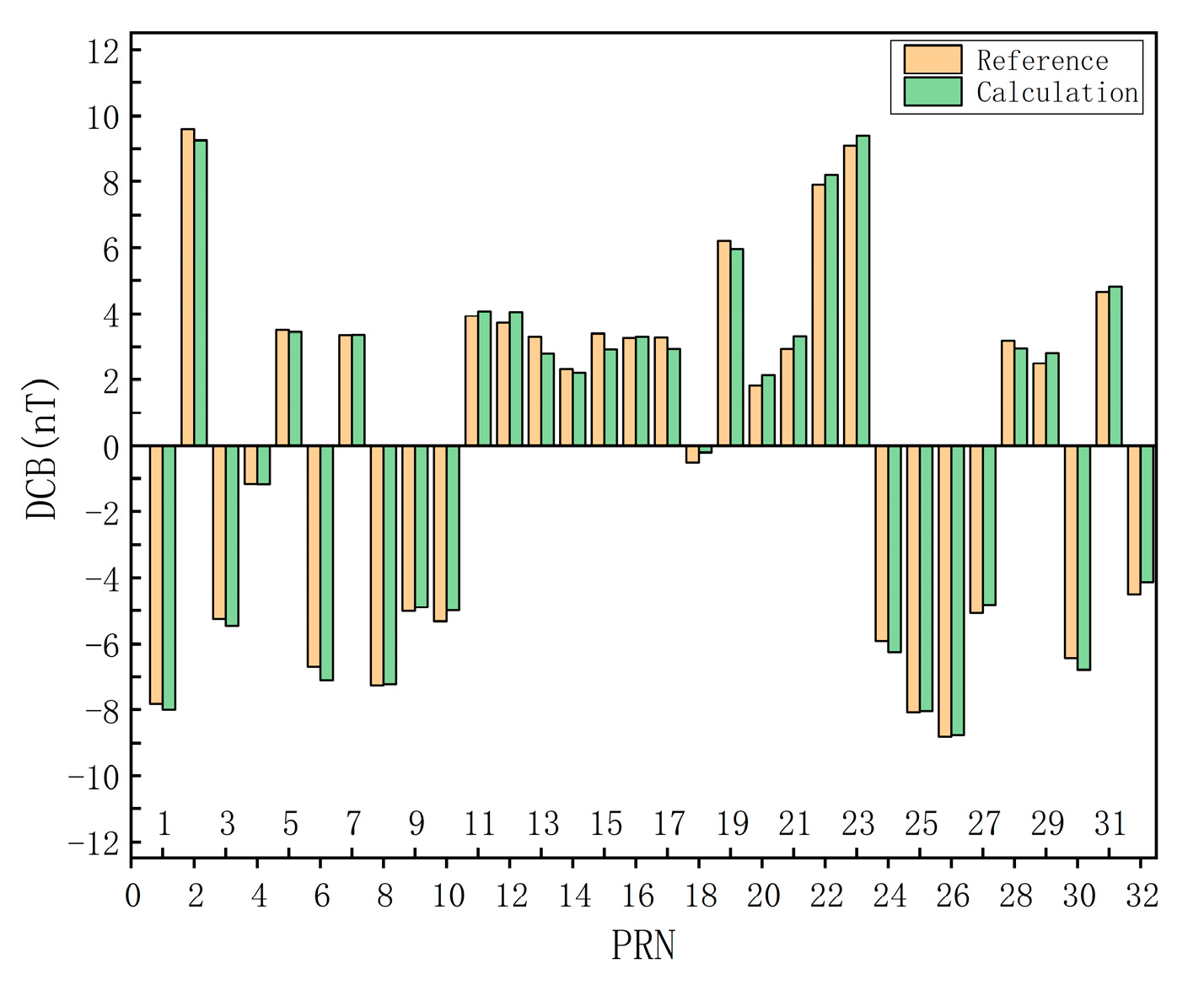

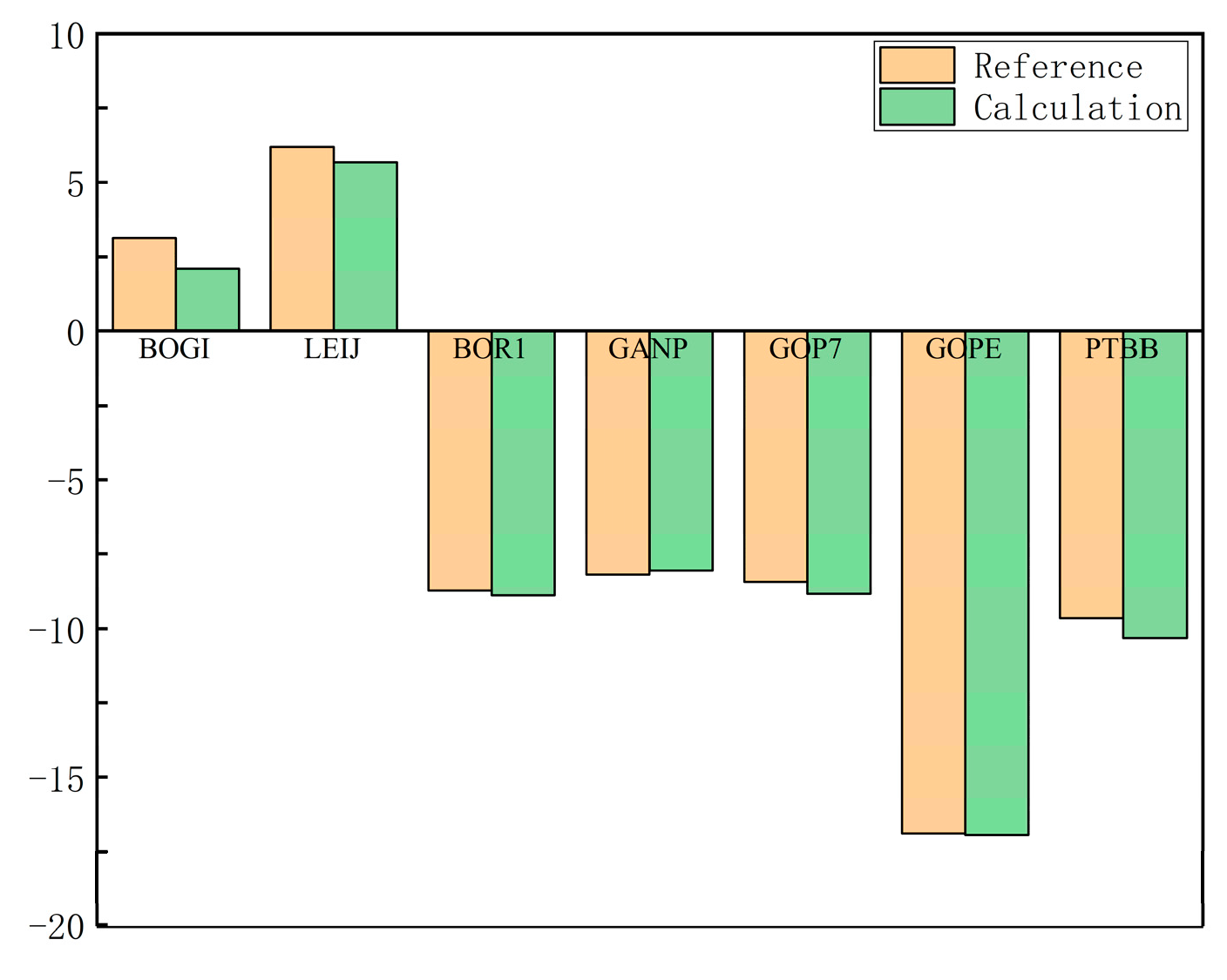

3.2. Accuracy Verification

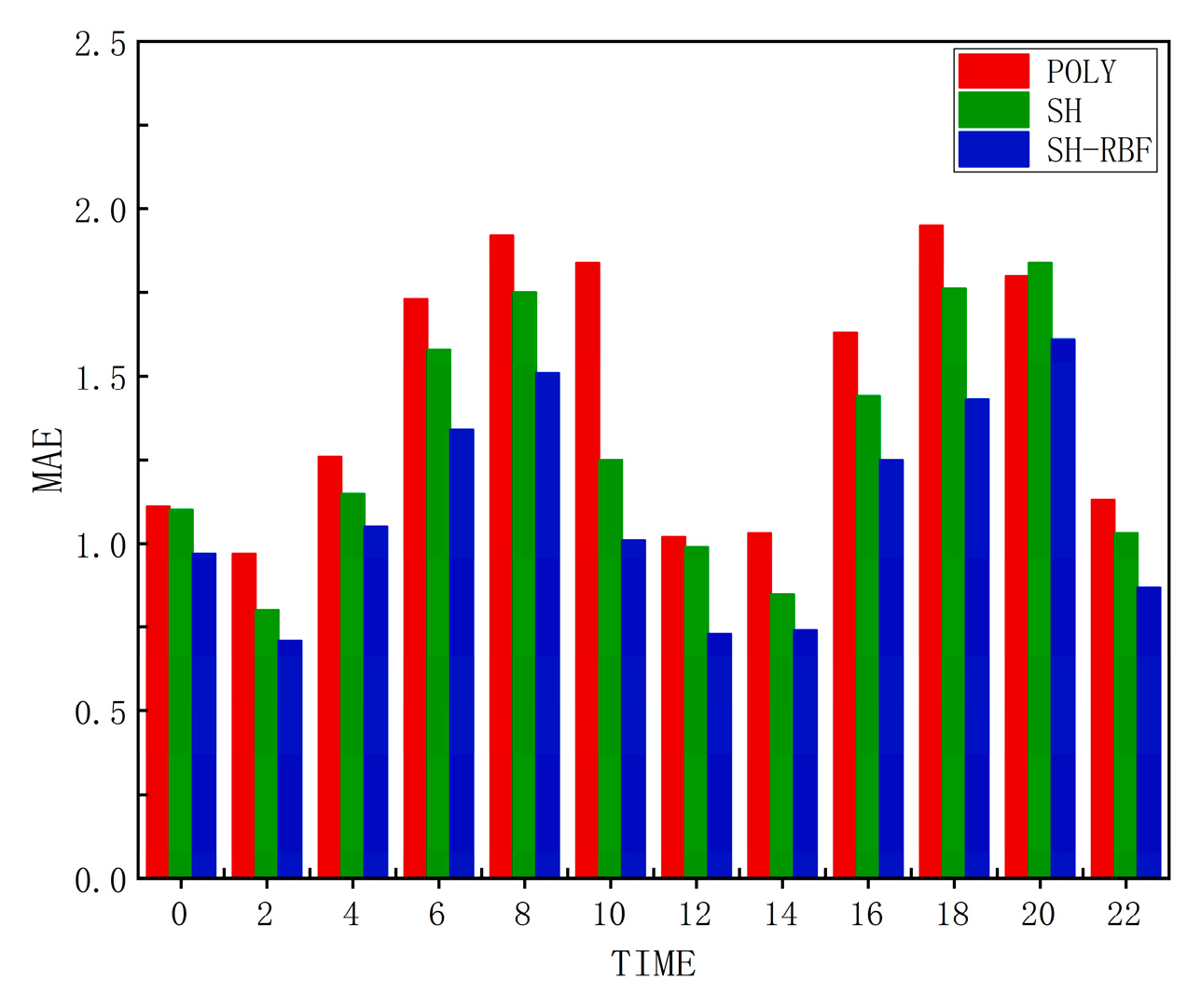

3.2.1. Geomagnetically Quiet Periods

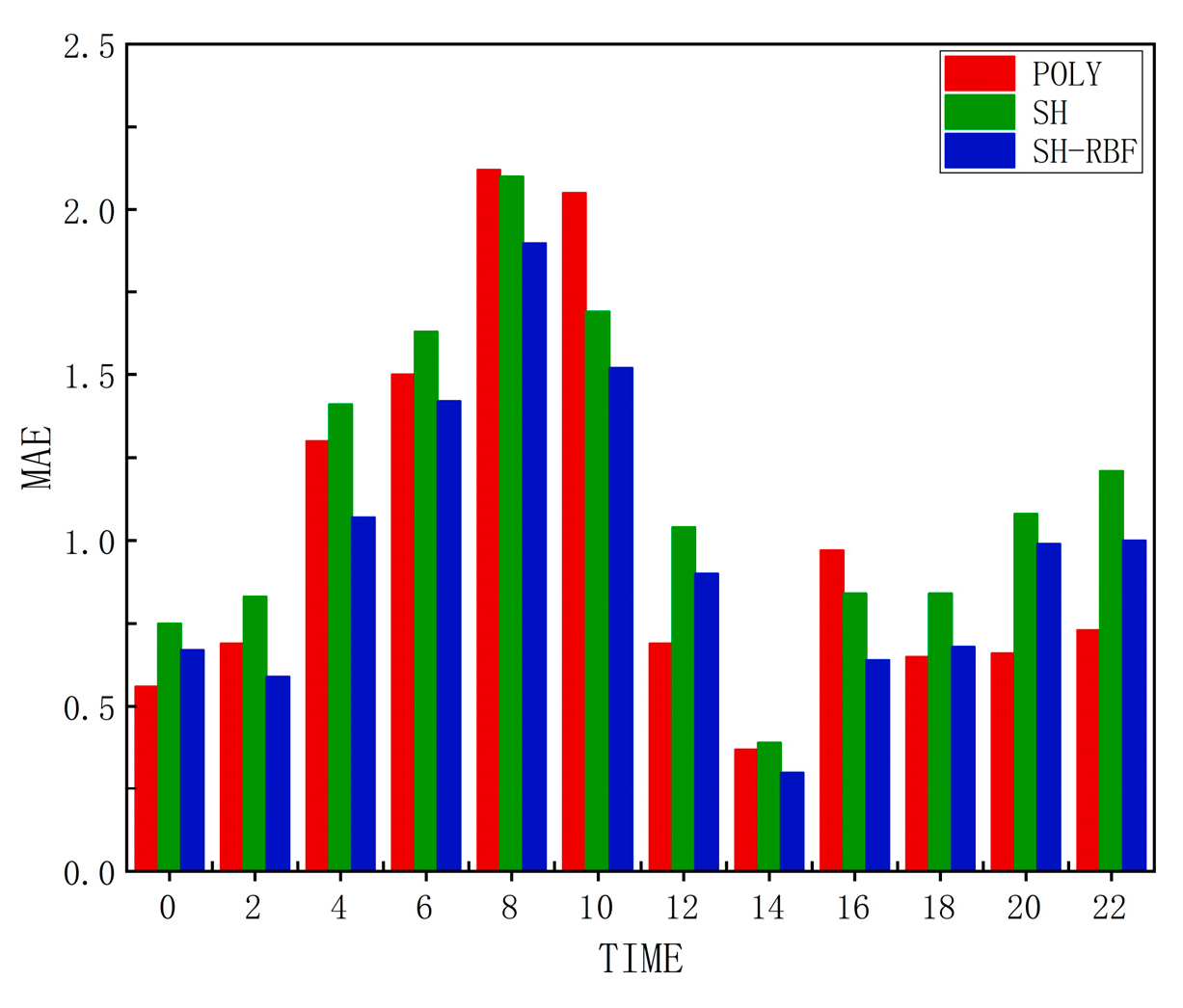

3.2.2. Geomagnetically Active Periods

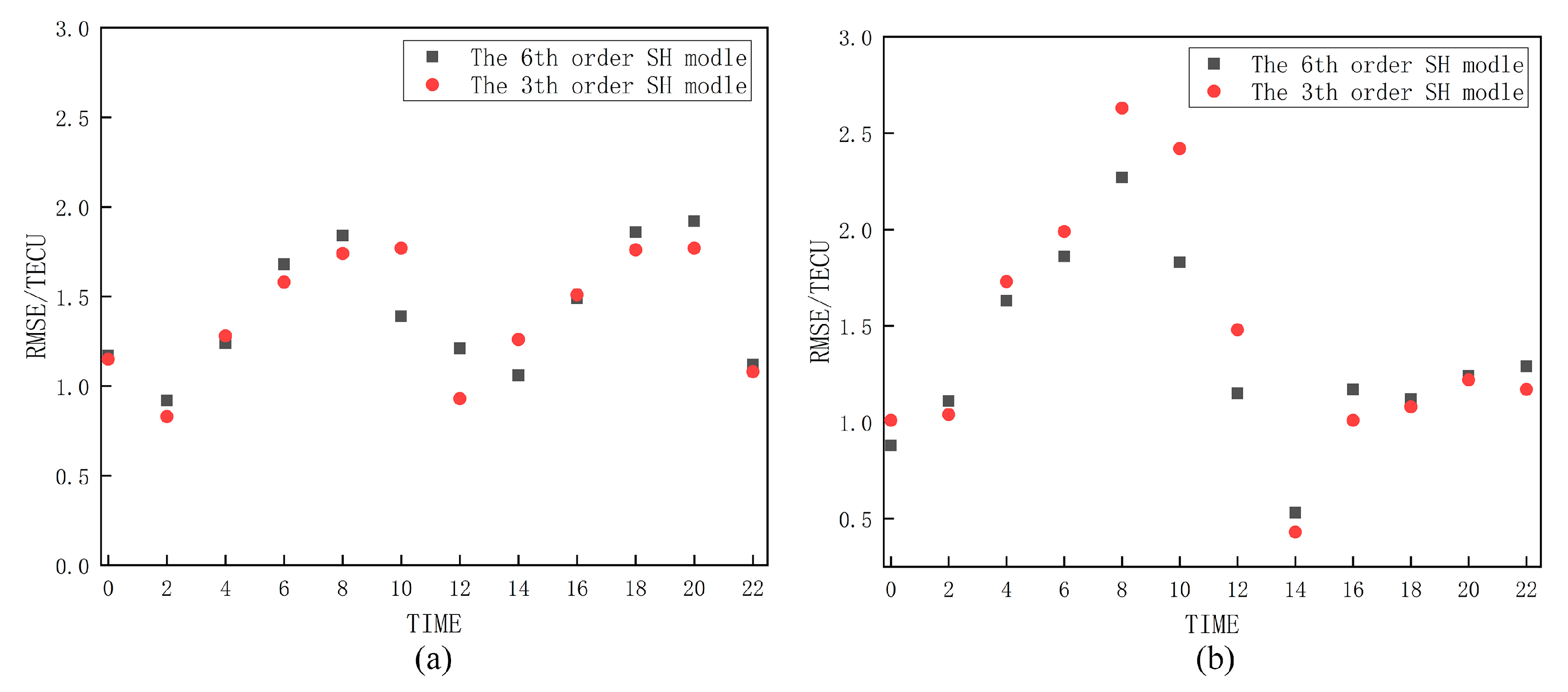

3.3. Analysis of Model Order and Modeling Accuracy

4. Discussion

4.1. Error Source Analysis

4.2. Selection of Optimal Model Order

4.3. Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The SH-RBF method significantly improves modeling accuracy, especially in boundary regions where traditional methods are prone to distortion. During geomagnetically quiet periods, the overall accuracy of SH-RBF was on average 14.49% higher than the SH method, with an average improvement of 53.51% in edge areas. The most effective corrections were observed during daytime, reaching 87.14%, while nighttime improvements were lower, with a minimum of 24.06%. During geomagnetically active periods, POLY outperformed spherical harmonics; however, SH-RBF not only showed superior accuracy in most cases, but also demonstrated significantly enhanced robustness throughout the day.

- (2)

- There is a clear relationship between the optimal order of spherical harmonics and the intensity of geomagnetic activity. Lower-order spherical harmonics suffice during quiet periods, whereas higher-order expansions are required during disturbed periods to resolve finer spatial scales.

- (3)

- Geomagnetic activity has a significant impact on ionospheric morphology. During active periods, both the peak value of ionospheric total electron content increased from 11.39 TECu in quiet periods to 14.32 TECu in this dataset, and the duration of ionospheric activity was prolonged. This reflects the substantial influence of space weather on ionospheric distribution and diurnal variation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Fan, L.; Shi, C.; Jing, G. A simplified worldwide ionospheric model for satellite navigation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 58, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovira-Garcia, A.; Ibáñez-Segura, D.; Orús-Perez, R.; Juan, J.M.; Sanz, J.; González-Casado, G. Assessing the quality of ionospheric models through GNSS positioning error: Methodology and results. GPS Solut. J. Glob. Navig. Satell. Syst. 2019, 24, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenbruck, O.; Steigenberger, P.; Khachikyan, R.; Weber, G.; Hugentobler, U. IGS-MGEX: Preparing the Ground for Multi-Constellation GNSS Science. Espace 2014, 9, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rizos, C.; Montenbruck, O.; Weber, R.; Weber, G.; Hugentobler, U. The IGS MGEX experiment as a milestone for a comprehensive multi-GNSS service. In Proceedings of the ION Pacific PNT Conference, Honolulu, Hawaii, 22–25 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lanyi, G.E.; Roth, T. A comparison of mapped and measured total ionospheric electron content using global positioning system and beacon satellite observations. Radio Sci. 1988, 23, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunbin, Y.; Jikun, O. A generalized trigonometric series function model for determining ionospheric delay*. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2004, 14, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, S. Mapping and Predicting the Earth’s Ionosphere Using the Global Positioning System; Geodaetisch-Geophysikalische Arbeiten in der Schweiz; Institut für Geodäsie und Photogrammetrie: Zürich, Switzerland, 1999; Volume 59. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Tscherning, C.C.; Knudsen, P.; Xu, G.; Ou, J. The ionospheric eclipse factor method (IEFM) and its application to determining the ionospheric delay for GPS. J. Geod. 2008, 82, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.J.R.K. Modeling and optimization of ionospheric model coefficients based on adjusted spherical harmonics function. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 182, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Li, Z.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Krankowski, A.; Yuan, H. SHAKING: Adjusted spherical harmonics adding KrigING method for near real-time ionospheric modeling with multi-GNSS observations. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 71, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhao, G.; Zang, N.; Cheng, S.; Chen, S.; Yao, J. A novel piecewise linear transformation to moderate regional boundary effect on Real-Time regional ionospheric map (RT-RIM). Measurement 2024, 236, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christovam, A.L.; Prol, F.S.; Jerez, G.O.; Hernández-Pajares, M.; Camargo, P.O. PPP at low latitudes with ionospheric model exclusively based on single frequency GNSS measurements. Space Weather 2023, 21, e2023SW003513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Pan, L. Impact of different receiver DCB correction methods on wide-area undifferenced slant ionospheric delay modeling for PPP-RTK. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 76, 6794–6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, K.; Liu, K. A novel slant ionospheric model for PPP-RTK by considering horizontal gradient discrepancies across stations. Measurement 2025, 257, 118888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ren, B.; Wu, F.; Liu, H.; Li, G.; Li, D. TECX-TCN: Prediction of ionospheric total electron content at different latitudes in China based on XGBoost algorithm and temporal convolution network. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2023, 249, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaselimi, M.; Voulodimos, A.; Doulamis, N.; Doulamis, A.; Delikaraoglou, D. A causal long short-term memory sequence to sequence model for TEC prediction using GNSS observations. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Ding, M. Prediction of ionospheric TEC using a GRU mechanism method. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, H.; Shi, S.; Zhao, D.; Shen, Y.; He, C. Modeling China’s Sichuan-Yunnan’s ionosphere based on multichannel WOA-CNN-LSTM algorithm. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5705018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, C.; Hu, M.; Xu, L.; Ding, M.; Xu, C. Research on GNSS ionospheric forecasting in China based on the BiLSTM-GRU-Attention model. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 76, 7031–7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aa, E.; Huang, W.; Yu, S.; Liu, S.; Shi, L.; Gong, J.; Chen, Y.; Shen, H. A regional ionospheric TEC mapping technique over China and adjacent areas on the basis of data assimilation. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2015, 120, 5049–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeot, N.; Chevalier, J.M.; Bruyninx, C.; Pottiaux, E.; Aerts, W.; Baire, Q.; Legrand, J.; Defraigne, P.; Huang, W. Near real-time ionospheric monitoring over Europe at the Royal Observatory of Belgium using GNSS data. J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2014, 4, a31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, N.; Hernandez-Pajares, M.; Huo, X. SHPTS: Towards a new method for generating precise global ionospheric TEC map based on spherical harmonic and generalized trigonometric series functions. J. Geod. 2015, 89, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rius, A.; Ruffini, G.; Cucurull, L. Improving the vertical resolution of ionospheric tomography with GPS Occultations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 24, 2291–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, K.; Romero-Andrade, R.; Sharma, G.; Colonna, R. Sequential Evolution of Ionospheric TEC Anomalies and Acoustic-Gravity Wave Precursors Associated with the February 8, 2025, Mw 7.6 Cayman Islands Earthquake. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2025, 274, 106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, S.; Steigenberger, P. Determination and use of GPS differential code bias values. In Proceedings of the IGS Workshop, Darmstadt, Germany, 8–12 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Multi-GNSS contributions to differential code biases determination and regional ionospheric modeling in China. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shi, C.; Fan, L.; Zhang, H. Improved Modeling of Global Ionospheric Total Electron Content Using Prior Information. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğanalp, S.; Köz, İ. Investigating Different Interpolation Methods for High-Accuracy VTEC Analysis in Ionospheric Research. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.L. Multiquadric equations of topography and other irregular surfaces. J. Geophys. Res. 1971, 76, 1905–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wu, Z. Stability of multiquadric quasi-interpolation to approximate high order derivatives. Sci. China Math. 2010, 53, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, P.P.; Aguilar, F.J.; Parente, C.; Aguilar, M.A. Statistical Assessment of Some Interpolation Methods for Building Grid Format Digital Bathymetric Models. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasshauer, G.E. Newton iteration with multiquadrics for the solution of nonlinear PDEs. Comput. Math. Appl. 2002, 43, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippa, S. An algorithm for selecting a good value for the parameter c in radial basis function interpolation. Adv. Comput. Math. 1999, 11, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardón, E.; Zarraoa, N. Estimation of total electron content using GPS data: How stable are the differential satellite and receiver instrumental biases? Radio Sci. 1997, 32, 1899–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaladze, T.; Pokhotelov, O.A.; Shah, H.; Khan, M.; Stenflo, L. Acoustic-gravity waves in the Earth’s ionosphere. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2008, 70, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DATE | Overall | Boundary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH | SH-RBF | SH | SH-RBF | |

| 29 September | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.89 | 0.30 |

| 30 September | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.96 | 0.29 |

| 1 October | 2.32 | 2.00 | 4.12 | 3.78 |

| 2 October | 1.06 | 0.90 | 1.22 | 0.37 |

| 3 October | 0.63 | 0.48 | 1.16 | 0.39 |

| 4 October | 0.90 | 0.80 | 1.22 | 0.49 |

| 5 October | 0.74 | 0.56 | 1.47 | 0.67 |

| UT | Overall | Boundary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLY | SH | SH-RBF | POLY | SH | SH-RBF | |

| 0 | 1.24 | 1.17 | 1.04 | 1.37 | 1.48 | 0.91 |

| 2 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.8 | 1.08 | 2.43 | 0.65 |

| 4 | 1.28 | 1.24 | 1.13 | 1.54 | 2.94 | 0.37 |

| 6 | 1.78 | 1.68 | 1.44 | 2.21 | 3.17 | 1.65 |

| 8 | 2.06 | 1.84 | 1.64 | 2.19 | 3.76 | 2.45 |

| 10 | 2.35 | 1.39 | 1.15 | 4.19 | 2.86 | 1.86 |

| 12 | 1.27 | 1.21 | 0.88 | 2.28 | 1.77 | 0.81 |

| 14 | 1.20 | 1.06 | 0.90 | 1.54 | 1.22 | 0.37 |

| 16 | 1.79 | 1.49 | 1.31 | 2.23 | 2.62 | 1.03 |

| 18 | 2.15 | 1.86 | 1.54 | 3.52 | 2.50 | 1.76 |

| 20 | 1.88 | 1.92 | 1.68 | 2.45 | 2.12 | 1.61 |

| 22 | 1.25 | 1.12 | 0.96 | 1.51 | 1.76 | 0.23 |

| DATE | Overall | Boundary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH | SH-RBF | SH | SH-RBF | |

| 11 May | 2.76 | 2.52 | 1.40 | 0.87 |

| 12 May | 1.52 | 1.37 | 2.05 | 0.99 |

| 13 May | 2.14 | 1.93 | 2.83 | 1.22 |

| 14 May | 0.53 | 0.39 | 1.22 | 0.37 |

| 15 May | 2.59 | 2.39 | 2.98 | 1.33 |

| 16 May | 1.05 | 0.92 | 1.5 | 0.72 |

| 17 May | 0.76 | 0.64 | 1.22 | 0.45 |

| UT | Overall | Boundary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLY | SH | SH-RBF | POLY | SH | SH-RBF | |

| 0 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 1.18 | 1.48 | 0.91 |

| 2 | 0.89 | 1.11 | 0.7 | 1.61 | 2.43 | 0.65 |

| 4 | 1.49 | 1.63 | 1.24 | 2.62 | 2.94 | 0.37 |

| 6 | 1.82 | 1.86 | 1.60 | 2.92 | 3.17 | 1.65 |

| 8 | 2.61 | 2.27 | 2.02 | 3.71 | 3.76 | 2.45 |

| 10 | 2.49 | 1.83 | 1.64 | 2.91 | 2.86 | 1.86 |

| 12 | 0.76 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 1.77 | 0.81 |

| 14 | 0.44 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 1.22 | 0.37 |

| 16 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 0.77 | 1.84 | 2.62 | 1.03 |

| 18 | 0.93 | 1.12 | 0.92 | 1.85 | 2.50 | 1.76 |

| 20 | 0.73 | 1.24 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 2.12 | 1.61 |

| 22 | 0.82 | 1.29 | 1.12 | 0.96 | 1.76 | 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yi, H.; Zhang, X.; Deng, W. A Symmetry-Coordinated Approach for Ionospheric Modeling: The SH-RBF Hybrid Model. Symmetry 2026, 18, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010072

Yi H, Zhang X, Deng W. A Symmetry-Coordinated Approach for Ionospheric Modeling: The SH-RBF Hybrid Model. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Hongmei, Xusheng Zhang, and Wenbin Deng. 2026. "A Symmetry-Coordinated Approach for Ionospheric Modeling: The SH-RBF Hybrid Model" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010072

APA StyleYi, H., Zhang, X., & Deng, W. (2026). A Symmetry-Coordinated Approach for Ionospheric Modeling: The SH-RBF Hybrid Model. Symmetry, 18(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010072