Evaluating Large Language Models on Chinese Zero Anaphora: A Symmetric Winograd-Style Minimal-Pair Benchmark

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Datasets for Chinese Zero Anaphora Resolution

- (1)

- 游客们可以在这里了解香港的电影史,Ø也可以在这里近距离接触自己心目中的明星。Visitors can explore the history of Hong Kong cinema here and even get close to the movie stars they admire.(OntoNotes example)

- (2)

- a 市议员拒绝给示威者颁发游行许可证,因为Ø害怕暴力。The city councilmen refused the demonstrators a permit because they feared violence.b 市议员拒绝给示威者颁发游行许可证,因为Ø提倡暴力。The city councilmen refused the demonstrators a permit because they advocated violence.(WSC-ZA minimal pairs)

2.2. Methods for Chinese Zero Anaphora Resolution

3. Winograd-Style Benchmark Construction

3.1. The Adaption of WSC to Chinese Zero Anaphora

- (3)

- a. 奖杯无法放进棕色的箱子里,因为Ø太大了。The trophy doesn’t fit into the brown suitcase because it’s too large.b. 奖杯无法放进棕色的箱子里,因为Ø太小了。The trophy doesn’t fit into the brown suitcase because it’s too small.

- (i)

- Objects of the ba-construction (e.g., (4)): The NP/pronoun following “ba” must be definite, and receives the patient role from the verb-complement complex. Without an overt NP/pronoun, the construction collapse because the verb lacks an argument to which its dispositional semantics can apply [38].

- (ii)

- Prenominal possessors (e.g., (5)): Chinese lacks independent possessive pronouns. Instead, possessors must be linked to the noun via “de”, forming an inseparable internal modifier. Most prenominal possessors function as obligatory modifiers rather than recoverable arguments [39] (Although kinship terms allow de-drop (e.g., “我妈妈” my mom), these forms remain obligatory attributive modifiers rather than recoverable arguments; therefore they do not license zero anaphora and were excluded).

- (iii)

- Direct-object pronouns of transitive verbs (e.g., (6)): Because zero objects in Chinese are rare and permitted only when discourse-recoverable [40], direct-object pronouns of transitive verbs, typically requiring a definite, interpretable object, can not be converted to zero anaphora.

- (iv)

- Other cases that do not fall into the above categories but violate basic licensing conditions for zero anaphora.

- (4)

- a. 我试着用钥匙开锁,但有人用口香糖堵住了锁眼,我无法把它插进去。I was trying to open the lock with the key, but someone had filled the keyhole with chewing gum, and I couldn’t get it in.b. *我试着用钥匙开锁,但有人用口香糖堵住了锁眼,我无法把Ø插进去。*I was trying to open the lock with the key, but someone had filled the keyhole with chewing gum, and I couldn’t get

itin. - (5)

- a. 那个男人把男孩放到了他的肩膀上。The man lifted the boy onto his shoulders.b. *那个男人把男孩放到了Ø的肩膀上。*The man lifted the boy onto

hisshoulders. - (6)

- a. 小明雇佣张峰来照顾他。John hired Bill to take care of him.b. *小明雇佣张峰来照顾Ø。*John hired Bill to take care of

him.

- (7)

- a. ?狐狸们晚上钻进来吃小鸡,Ø越来越大胆。The foxes are getting in at night and attacking the chickens. They have gotten very bold.b.狐狸们晚上钻进来吃小鸡,Ø真是越来越大胆。The foxes are getting in at night and attacking the chickens. They have gotten very bold.

- (8)

- a. ?小明把椅子拉到钢琴前,但Ø是坏的,所以他只好站着。Sam pulled up a chair to the piano, but it was broken, so he had to stand instead.b. 小明把椅子拉到钢琴旁,但是Ø是坏的,所以他只好站着。Sam pulled up a chair to the piano, but it was broken, so he had to stand instead.

- (9)

- a. *老生欺负新生,所以我们惩罚了Ø。The older students were bullying the younger ones, so they got our punishment.b. 老生欺负新生,所以Ø得到了我们的惩罚。The older students were bullying the younger ones, so they got our punishment.

- (10)

- a. *父亲把熟睡的男孩放进了Ø的摇篮。The father carried the sleeping boy in his bassinet.b.父亲把熟睡的男孩放进了Ø

的摇篮里。The father carried the sleeping boy in his bassinet.

3.2. Validation of WSC-ZA

- Easy Items: Naturalness rating ≥ 4.0;

- Moderate Items: 3.0 ≤ Naturalness rating < 4.0;

- Hard Items: Naturalness rating < 3.0.

3.3. Human Upper Bound

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. First Experiment: Quantitative Evaluation

4.1.1. Models Evaluated

4.1.2. Prompting Paradigms

- Zero-shot Prompting: Test cases were presented as prompts without providing the model with any prior examples.

- One-shot prompting: Test cases were preceded by one fixed example illustrating a zero anaphora instance and its correct resolution.

- Few-shot prompting: Test cases were preceded by three input–output examples to show the model how the task works.

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Micro Accuracy

- Item-level Accuracy

- Mode-level Accuracy

- Precision

- Recall

- F1-Score

4.2. Second Experiment: Chain-of-Thought Error Analysis

- Identify errors: Extract all items where the model’s prediction differed from the gold answer.

- Apply CoT diagnostic prompt: Re-run each misclassified item using a standardized CoT template, which instructs the model to re-evaluate the sentence, compare the antecedent candidates, and explain why the previous answer was incorrect. The full CoT template is provided in Appendix C.

- Generate explanations: Obtain step-by-step reasoning traces from all three models.

- Classify error types: Manually code each explanation to determine the source of error.

- Analyze patterns: Summarize error distributions and examine representative cases.

5. Results

5.1. Model Performance Comparison

5.2. Comparison with Human Upper Bound

5.3. Item-Level Accuracy Results

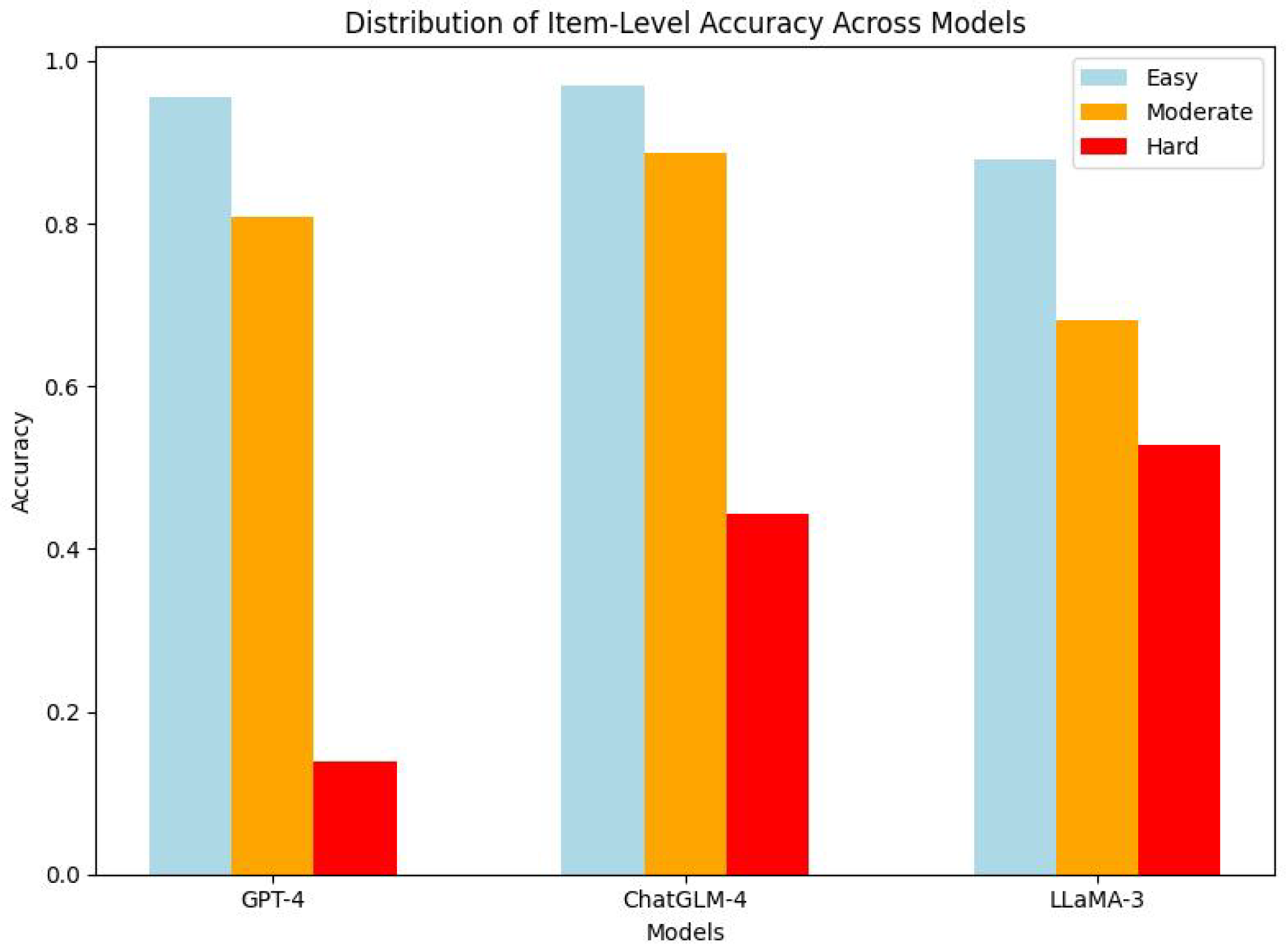

- Easy Items: Accuracy ≥ 0.85;

- Moderate Items: 0.60 ≤ Accuracy < 0.85;

- Hard Items: Accuracy < 0.60.

5.3.1. Performance by Difficulty Level

- GPT-4 shows strong performance on easy items (0.956), with a slight decline to 0.809 on moderate items. However, it experiences a sharp decline in performance on hard items, with accuracy dropping to 0.139. This significant drop indicates that GPT-4 struggles the most with more complex cases, particularly on hard items.

- ChatGLM-4 performs best on easy items (0.969), with a slight drop to 0.887 on moderate items. Similarly to GPT-4, ChatGLM-4 also shows a sharp decline on hard items, with accuracy dropping to 0.444. While the decline from easy to hard is steep, it is less pronounced than GPT-4′s performance on hard items.

- LLaMA-3 demonstrates the highest accuracy on both moderate items (0.681) and hard items (0.528) compared to the other models, suggesting that it handles more complex cases better. However, its performance on easy items (0.878) is lower than that of GPT-4 and ChatGLM-4, indicating that it is less effective on simpler tasks.

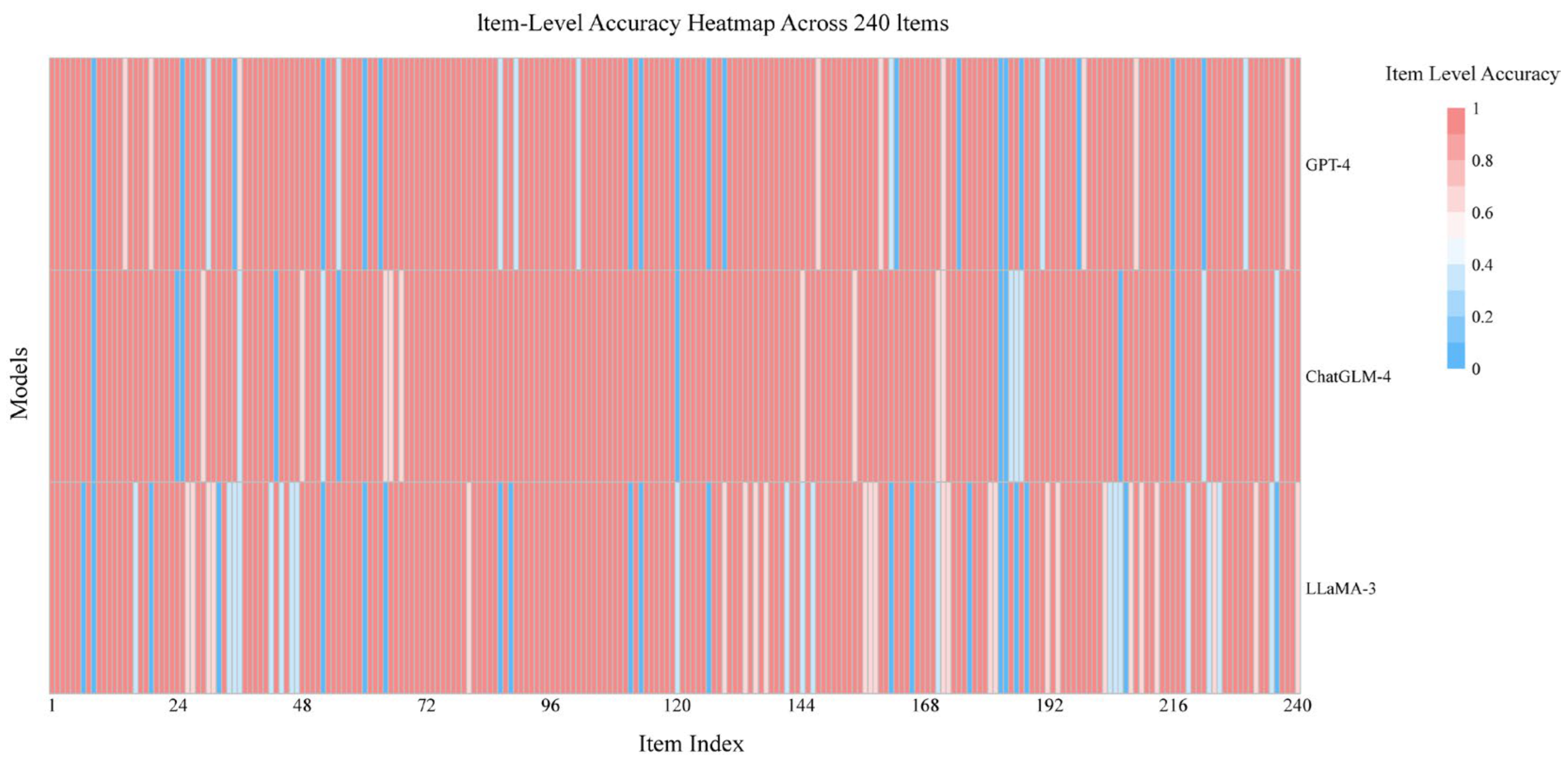

5.3.2. Item-Level Performance Variations

- ChatGLM-4 is the most consistent model, demonstrating high accuracy across most items, though it still encounters occasional challenges on particularly difficult items, as reflected in sporadic blue patches.

- GPT-4 performs well on easy items but exhibits variations on harder items. Its error distribution is similar to LLaMA-3, suggesting both models struggle with more complex cases.

- LLaMA-3 displays more variability, particularly on hard items, where it struggles the most, as indicated by frequent blue patches. It has the lowest overall accuracy among the models, with more mistakes on challenging items compared to ChatGLM-4 and GPT-4.

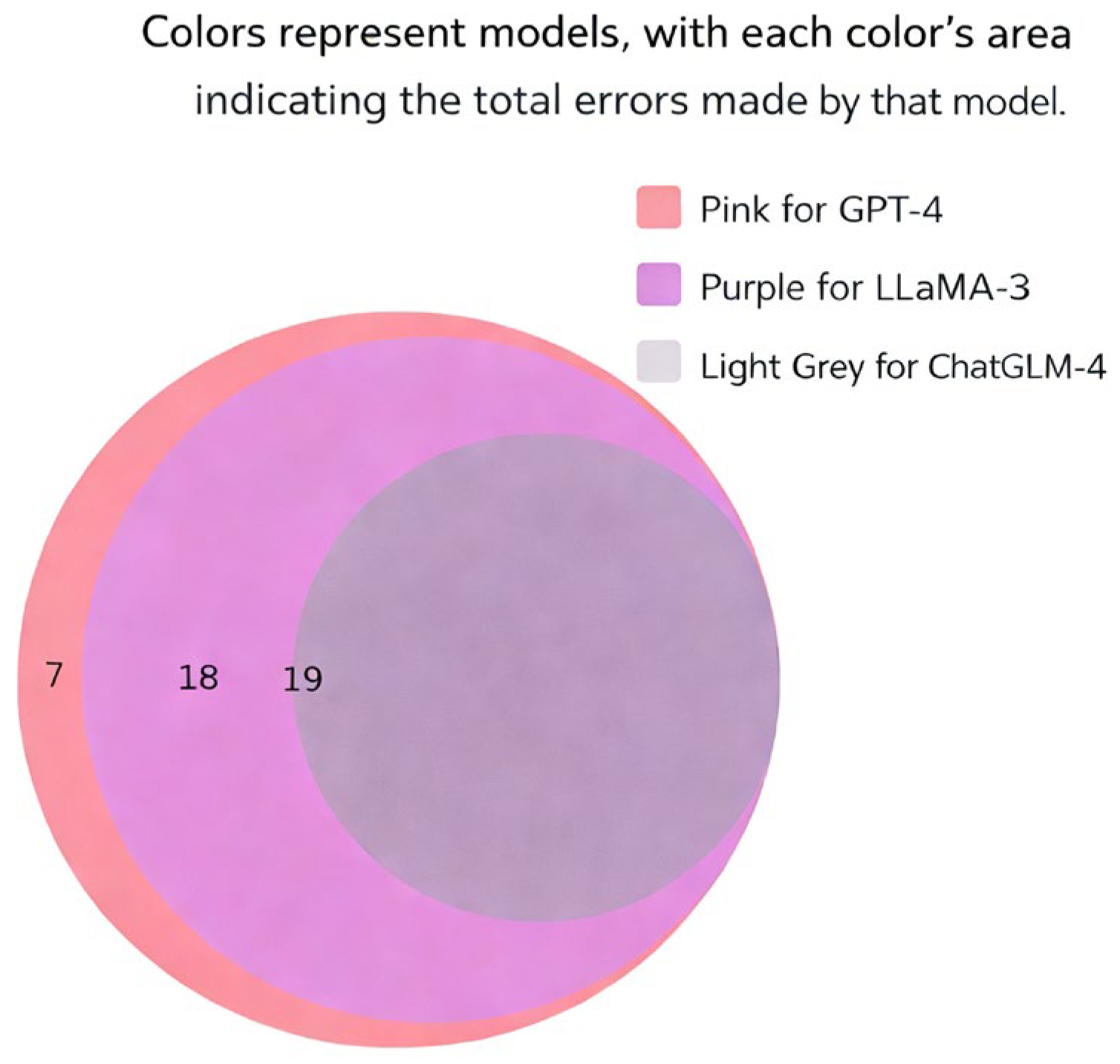

5.4. Error Overlap Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Model-Level Insights and Implications

6.2. Interpreting the Gap Between LLMs and the Human Upper Bound

6.3. Effects of Item Difficulty on Model Performance

6.4. Systematic Error Patterns

- (11)

- 建国得到了免费的歌剧票,但他给了李广,因为Ø特别想看。

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | Variant/ Parameters | Training Background | Inference Setup |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 | Not publicly disclosed (estimated >1T parameters, mixture-of-experts) | Multilingual, broad-domain, large-scale web + curated corpora | OpenAI API; temperature = 0; max_tokens = 128 |

| ChatGLM-4.6 | 6B parameters | Chinese-centric; dialog + web text; optimized for Chinese syntax and semantics | API/local; temperature = 0; top_p = 0.9; max_tokens = 128 |

| LLaMA-3 | 70B open-source variants | Trained on 15T multilingual tokens | Local HF or llama.cpp; temperature = 0 |

Appendix B

- Zero-Shot Template

- One-Shot Template

- Few-Shot Template

Appendix C

References

- Hartmann, R.R.K.; Stork, F.C. Dictionary of Language and Linguistics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Anaphora: A Cross-Linguistic Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Konno, R.; Kiyono, S.; Matsubayashi, Y.; Ouchi, H.; Inui, K. Pseudo zero pronoun resolution improves zero anaphora resolution. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.07425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Li, J.; Ye, X.; Qu, W. Hierarchical Discourse-Semantic Modeling for Zero Pronoun Resolution in Chinese. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Eugenio, B. Centering theory and the Italian pronominal system. In Proceedings of the COLING 1990 Volume 2: Papers Presented to the 13th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Helsinki, Finland, 20–25 August 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrández, A.; Palomar, M.; Moreno, L. An empirical approach to Spanish anaphora resolution. Mach. Transl. 1999, 14, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, R.; Inui, K.; Matsumoto, Y. Exploiting syntactic patterns as clues in zero-anaphora resolution. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and the 44th annual meeting of the ACL-ACL’06, Sydney, Australia, 17–21 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Ra, D.; Lim, S. Zero-anaphora resolution in Korean based on deep language representation model: BERT. ETRI J. 2021, 43, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, M.-M. Zero anaphora and topic chain in Chinese discourse. In The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Discourse Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 188–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, L.; Healy, A.F. Zero anaphora: Transfer of reference tracking strategies from Chinese to English. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2005, 34, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, Y.; Wei, W.; Yang, C. Resolving Linguistic Asymmetry: Forging Symmetric Multilingual Embeddings Through Asymmetric Contrastive and Curriculum Learning. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ng, H.T. Identification and resolution of Chinese zero pronouns: A machine learning approach. In Proceedings of the 2007 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning (EMNLP-CoNLL), Prague, Czech Republic, 28–30 June 2007; pp. 541–550. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, F.; Zhou, G. A tree kernel-based unified framework for Chinese zero anaphora resolution. In Proceedings of the 2010 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Cambridge, MA, USA, 9–11 October 2010; pp. 882–891. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Ng, V. Chinese zero pronoun resolution: Some recent advances. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–21 October 2013; pp. 1360–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T. A deep neural network for chinese zero pronoun resolution. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1604.05800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, T. Chinese zero pronoun resolution with deep memory network. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–11 September 2017; pp. 1309–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, K.; Recasens, M.; Axelrod, V.; Baldridge, J. Mind the GAP: A balanced corpus of gendered ambiguous pronouns. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 6, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poesio, M.; Yu, J.; Paun, S.; Aloraini, A.; Lu, P.; Haber, J.; Cokal, D. Computational models of anaphora. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 2023, 9, 561–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, H.J. The winograd schema challenge. In Proceedings of the AAAI Spring Symposium: Logical Formalizations of Commonsense Reasoning, Stanford, CA, USA, 21–23 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.; Shi, X.; Liu, X. Symmetry-and Asymmetry-Aware Dual-Path Retrieval and In-Context Learning-Based LLM for Equipment Relation Extraction. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, T.; Han, T. Mandarinograd: A Chinese collection of Winograd schemas. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Hu, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Cao, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Sun, K.; Yu, D.; Yu, C. CLUE: A Chinese language understanding evaluation benchmark. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, J.; Ma, L.; Lu, Z. A study of zero anaphora resolution in Chinese discourse: From the perspective of psycholinguistics. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 663168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Z. Machine reading comprehension combined with semantic dependency for Chinese zero pronoun resolution. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 7597–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ng, V. Chinese zero pronoun resolution: A joint unsupervised discourse-aware model rivaling state-of-the-art resolvers. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015; Short Papers. Volume 2, pp. 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Wang, W.Y. Zero pronoun resolution with attention-based neural network. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–26 August 2018; pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.; Yang, M. Hierarchical attention network with pairwise loss for Chinese zero pronoun resolution. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 8352–8359. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Cui, Y.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Hu, G. Generating and exploiting large-scale pseudo training data for zero pronoun resolution. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; Long Papers. Volume 1, pp. 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, D. ZPR2: Joint zero pronoun recovery and resolution using multi-task learning and BERT. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 5429–5434. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Gu, B.; Qu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, A.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Z. Tackling zero pronoun resolution and non-zero coreference resolution jointly. In Proceedings of the 25th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, Online, 20–24 November 2021; pp. 518–527. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Xu, K.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Gao, S.; Guo, J.; Wen, J.-R.; Xue, N. Transformer-GCRF: Recovering chinese dropped pronouns with general conditional random fields. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.03224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, M.; Song, L.; Shi, S.; Tu, Z. A survey on zero pronoun translation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.T.; Ritter, A. Are large language models robust coreference resolvers? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueyama, A.; Kano, Y. Dialogue Response Generation Using Completion of Omitted Predicate Arguments Based on Zero Anaphora Resolution. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, Prague, Czechia, 11–15 September 2023; pp. 282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, H.J.; Davis, E.; Morgenstern, L. The Winograd schema challenge. KR 2012, 2012, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Wei, X. Addressing Asymmetry in Contrastive Learning: LLM-Driven Sentence Embeddings with Ranking and Label Smoothing. Symmetry 2025, 17, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Resolving chinese anaphora with chatgpt. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Asian Language Processing (IALP), Hohhot, China, 4–6 August 2024; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, T.; Wang, C. Object preposing in mandarin chinese. J. East Asian Linguist. 1995, 4, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y. Explicitation of personal pronoun subject in Chinese EFL majors’ translation: A case study of translation universals based on PACCEL-W corpus. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2015, 6, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.N.; Thompson, S.A. Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, C.T. The Empirical Base of Linguistics: Grammaticality Judgements and Linguistic Methodology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sprouse, J.; Schütze, C.T.; Almeida, D. A comparison of informal and formal acceptability judgments using a random sample from Linguistic Inquiry 2001–2010. Lingua 2013, 134, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowart, W. Experimental Syntax: Applying Objective Methods to Sentence Judgments; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brezina, V. Classical monofactorial (parametric and non-parametric) tests. In A Practical Handbook of Corpus Linguistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 473–503. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustejovsky, J.; Stubbs, A. Natural Language Annotation for Machine Learning: A Guide to Corpus-Building for Applications; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi, K.; Le Bras, R.; Bhagavatula, C.; Choi, Y. Winogrande: An adversarial winograd schema challenge at scale. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 8732–8740. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.; Morgenstern, L.; Ortiz, C. Human Tests of Materials for the Winograd Schema Challenge; New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2016. Available online: https://cs.nyu.edu/faculty/davise/papers/WS2016SubjectTests.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Kehler, A.; Kehler, A. Coherence, Reference, and the Theory of Grammar; CSLI Publications: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 380. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, A.; De La Cruz, N.; Trischler, A.; Suleman, K.; Cheung, J.C.K. A knowledge hunting framework for common sense reasoning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.01375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 1971, 76, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Qian, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, M.; Qiu, J.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J. Glm: General language model pretraining with autoregressive blank infilling. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Long papers. Volume 1, pp. 320–335. [Google Scholar]

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, T.; Gu, S.S.; Reid, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Iwasawa, Y. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 22199–22213. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.; Lyu, X.; Holtzman, A.; Artetxe, M.; Lewis, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Zettlemoyer, L. Rethinking the role of demonstrations: What makes in-context learning work? arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.12837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Stano, P.; Horák, A. Evaluating Prompt-Based and Fine-Tuned Approaches to Czech Anaphora Resolution. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Text, Speech, and Dialogue, Erlangen Nürnberg, Germany, 25–28 August 2025; pp. 190–202. [Google Scholar]

- Madotto, A.; Lin, Z.; Winata, G.I.; Fung, P. Few-shot bot: Prompt-based learning for dialogue systems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.08118. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, 45, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, M.; Andreassen, A.J.; Gur-Ari, G.; Michalewski, H.; Austin, J.; Bieber, D.; Dohan, D.; Lewkowycz, A.; Bosma, M.; Luan, D. Show your work: Scratchpads for intermediate computation with language models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.00114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, J.; Dušek, O.; Rieser, V. RankME: Reliable human ratings for natural language generation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.05928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuff, H.; Vanderlyn, L.; Adel, H.; Vu, N.T. How to do human evaluation: A brief introduction to user studies in NLP. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2023, 29, 1199–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wei, H.-R.; Lin, H.; Li, T.; Yang, B.; Huang, F.; Lu, W. Enhancing LLM language adaption through cross-lingual in-context pre-training. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Suzhou, China, 4-9 November 2025; pp. 27140–27154. [Google Scholar]

- Poesio, M.; Stuckardt, R.; Versley, Y. Anaphora Resolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Charlow, S.; Frank, R. Do LLMs Understand Anaphora Accessibility? Soc. Comput. Linguist. 2025, 8, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Kocijan, V.; Davis, E.; Lukasiewicz, T.; Marcus, G.; Morgenstern, L. The defeat of the Winograd schema challenge. Artif. Intell. 2023, 325, 103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, J.; Ahnert, G.; Strohmaier, M. Prompt perturbations reveal human-like biases in llm survey responses. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.07188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondorf, P.; Plank, B. Beyond accuracy: Evaluating the reasoning behavior of large Language models--A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.01869. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.; Patrawala, A.; Steinhardt, J. Uncovering gaps in how humans and LLMs interpret subjective language. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.04113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Han, Y. MIRA-ChatGLM: A Fine-Tuned Large Language Model for Intelligent Risk Assessment in Coal Mining. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E. Logical formalizations of commonsense reasoning: A survey. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2017, 59, 651–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Song, Y. WinoWhy: A deep diagnosis of essential commonsense knowledge for answering Winograd schema challenge. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.05763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Cheung, H.; Tang, S.L.; Wong, Y.T. Effects of antecedent order and semantic context on Chinese pronoun resolution. Mem. Cogn. 2000, 28, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Goyal, V.; Kaur, K. A detailed study on anaphora resolution system for asian languages. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, N.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Lin, H.; Lu, Y.; He, B.; Jiang, S.; Dong, B. Chatgpt is a knowledgeable but inexperienced solver: An investigation of commonsense problem in large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.16421. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, X. Topic shift impairs pronoun resolution during sentence comprehension: Evidence from event-related potentials. Psychophysiology 2016, 53, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madge, C.; Purver, M.; Poesio, M. Referential ambiguity and clarification requests: Comparing human and LLM behaviour. In Proceedings of the Eighth Workshop on Computational Models of Reference, Anaphora and Coreference, Suzhou, China, 9 November 2025; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | OntoNotes Zero Pronouns | WSC-ZA Minimal Pairs |

|---|---|---|

| antecedent options | usually single | always two competing |

| ambiguity source | natural discourse | controlled pragmatic alternation |

| inference demand | recovery | reasoning |

| difficulty nature | uncontrolled, uneven | systematic, maximal |

| task type | resolution | inference |

| Sentences | Number | Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| original sentences | 284 | - | - |

| sentences removed for grammatical reasons | 6 | objects of the ba-construction | see example (4) |

| 20 | most prenominal possessors | see example (5) | |

| 8 | direct-object pronouns of transitive verbs | see example (6) | |

| 10 | others | - | |

| modified sentences | 2 | adding stance adverbials | see example (7) |

| 2 | inserting copular elements | see example (8) | |

| 2 | rephrasing predicates | see example (9) | |

| 8 | a few prenominal possessors | see example (10) |

| Difficulty Level | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Easy | 4.73 | 0.44 |

| Moderate | 3.05 | 0.47 |

| Hard | 1.75 | 0.44 |

| Metric | Mean Accuracy | SD | N | 95%CI Lower | 95%CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject-level Accuracy (Human Upper Bound) | 0.926 | 0.037 | 24 | 0.9106 | 0.9422 |

| Item-level Accuracy | 0.926 | 0.165 | 240 | 0.9054 | 0.9474 |

| Overall Micro Accuracy | 0.926 | - | 1440 | - | - |

| Model | Zero-Shot | One-Shot | Few-Shot |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 | 0.883 | 0.892 | 0.883 |

| ChatGLM-4 | 0.921 | 0.929 | 0.929 |

| LLaMA-3 | 0.849 | 0.792 | 0.824 |

| Model | Prompting Condition | Macro-Precision | Macro-Recall | Macro-F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 | Zero-shot | 0.883 | 0.883 | 0.883 |

| One-shot | 0.892 | 0.892 | 0.892 | |

| Few-shot | 0.883 | 0.883 | 0.883 | |

| ChatGLM-4 | Zero-shot | 0.913 | 0.913 | 0.912 |

| One-shot | 0.933 | 0.933 | 0.933 | |

| Few-shot | 0.929 | 0.929 | 0.929 | |

| LLaMA-3 | Zero-shot | 0.850 | 0.846 | 0.845 |

| One-shot | 0.779 | 0.779 | 0.779 | |

| Few-shot | 0.826 | 0.821 | 0.820 |

| Model Comparison | t-Statistic | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 vs. ChatGLM-4 | −2.20 | 0.029 | Statistically Significant |

| GPT-4 vs. LLaMA-3 | 2.73 | 0.007 | Statistically Significant |

| ChatGLM-4 vs. GPT-4 | 2.20 | 0.029 | Statistically Significant |

| ChatGLM-4 vs. LLaMA-3 | 4.65 | 5.61 × 10−0.6 | Highly Statistically Significant |

| LLaMA-3 vs. GPT-4 | −2.73 | 0.007 | Statistically Significant |

| LLaMA-3 vs. ChatGLM-4 | −4.65 | 5.61× 10−0.6 | Highly Statistically Significant |

| Error Type | Definition | Example | Number (N = 19) and Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Cue Misguidance | Model is misled by linear proximity, salience bias, or shallow lexical cues. | 小明把椅子拉到钢琴旁,但是Ø是坏的,所以他只好唱歌。 Sam pulled up a chair to the piano, but it was broken, so he had to sing instead. (Ø = piano) | 16 (84.2%) |

| Semantic Role Conflict | Confusion of agent/theme/experiencer roles; ambiguous predicate–argument structure. | 志明对老王很生气,因为Ø买自他的吐司机是坏的。 Frank was upset with Tom because the toaster he had bought from him didn’t work. (Ø = Frank) | 14 (73.7%) |

| Pragmatic & Commonsense Reasoning | Requires world knowledge: spatial, temporal, emotional, property, container–content, motivation, stereotypes. | 这张桌子不能通过门口,因为ø太窄了。 The table won’t fit through the doorway because it is too narrow. (Ø = doorway) | 13 (68.4%) |

| Topic-Chain Ambiguity | Weak or disrupted discourse topic continuity; unclear topic prominence. | 建国是唯一在世而且记得我父亲婴儿时样子的人。第一次见到我父亲时,Ø才十二个月大。 Fred is the only man alive who still remembers my father as an infant. When Fred first saw my father, he was twelve months old. (Ø = my father) | 6 (31.6%) |

| Logical Connective Misinterpretation | Causal/concessive markers (因为 because, 但是 but, 尽管 although) incorrectly parsed. | 建国得到了免费的歌剧票,但他给了李广,因为Ø特别想看。 George got free tickets to the play, but he gave them to Eric, because he was particularly eager to see it. (Ø = Eric) | 5 (26.3%) |

| Long-Distance Dependency | Antecedent requires maintaining reference over longer spans; missing cues. | 建国是唯一在世而且记得我父亲婴儿时样子的人。第一次见到我父亲时,Ø才十二个月大。 Fred is the only man alive who still remembers my father as an infant. When Fred first saw my father, he was twelve months old. (Ø = my father) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Syntactic Ambiguity | Multiple grammatically valid antecedents; structural ambiguity. | 李静很乐意用她的毛衣交换我的夹克。她觉得Ø穿在身上显得很土气。 Grace was happy to trade me her sweater for my jacket. She thinks it looks dowdy on her. (Ø = sweater) | 2 (10.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, S. Evaluating Large Language Models on Chinese Zero Anaphora: A Symmetric Winograd-Style Minimal-Pair Benchmark. Symmetry 2026, 18, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010047

Li Z, Qiao Y, Chen X, Chen S. Evaluating Large Language Models on Chinese Zero Anaphora: A Symmetric Winograd-Style Minimal-Pair Benchmark. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zimeng, Yichen Qiao, Xiaoran Chen, and Shuangshuang Chen. 2026. "Evaluating Large Language Models on Chinese Zero Anaphora: A Symmetric Winograd-Style Minimal-Pair Benchmark" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010047

APA StyleLi, Z., Qiao, Y., Chen, X., & Chen, S. (2026). Evaluating Large Language Models on Chinese Zero Anaphora: A Symmetric Winograd-Style Minimal-Pair Benchmark. Symmetry, 18(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010047