First-Principles Investigation of Structural, Electronic, and Elastic Properties of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 Chalcopyrite Alloys Using GGA+U

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calculation Method

3. Results and Discussion

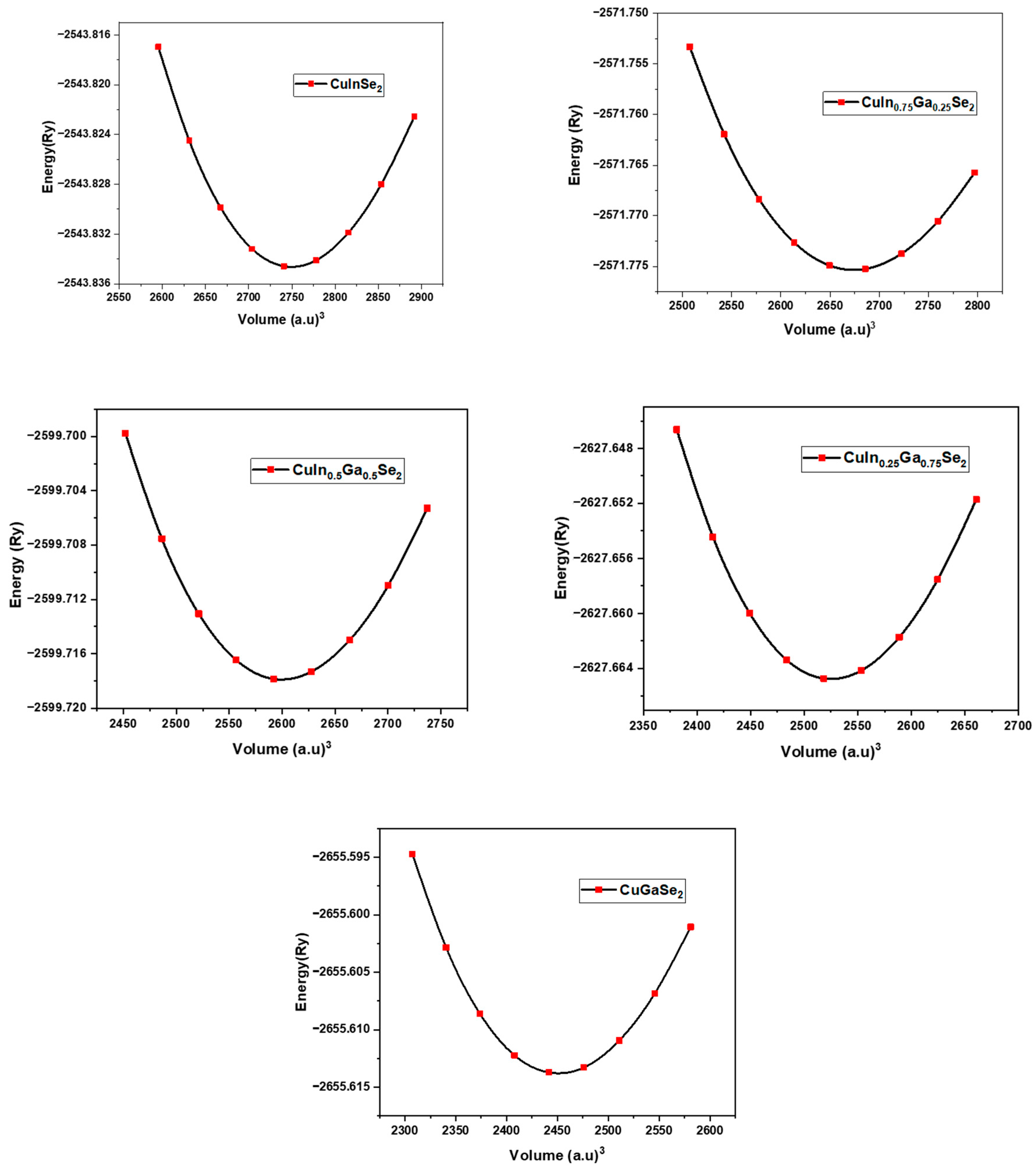

3.1. Structural Properties

3.2. Structural Stability

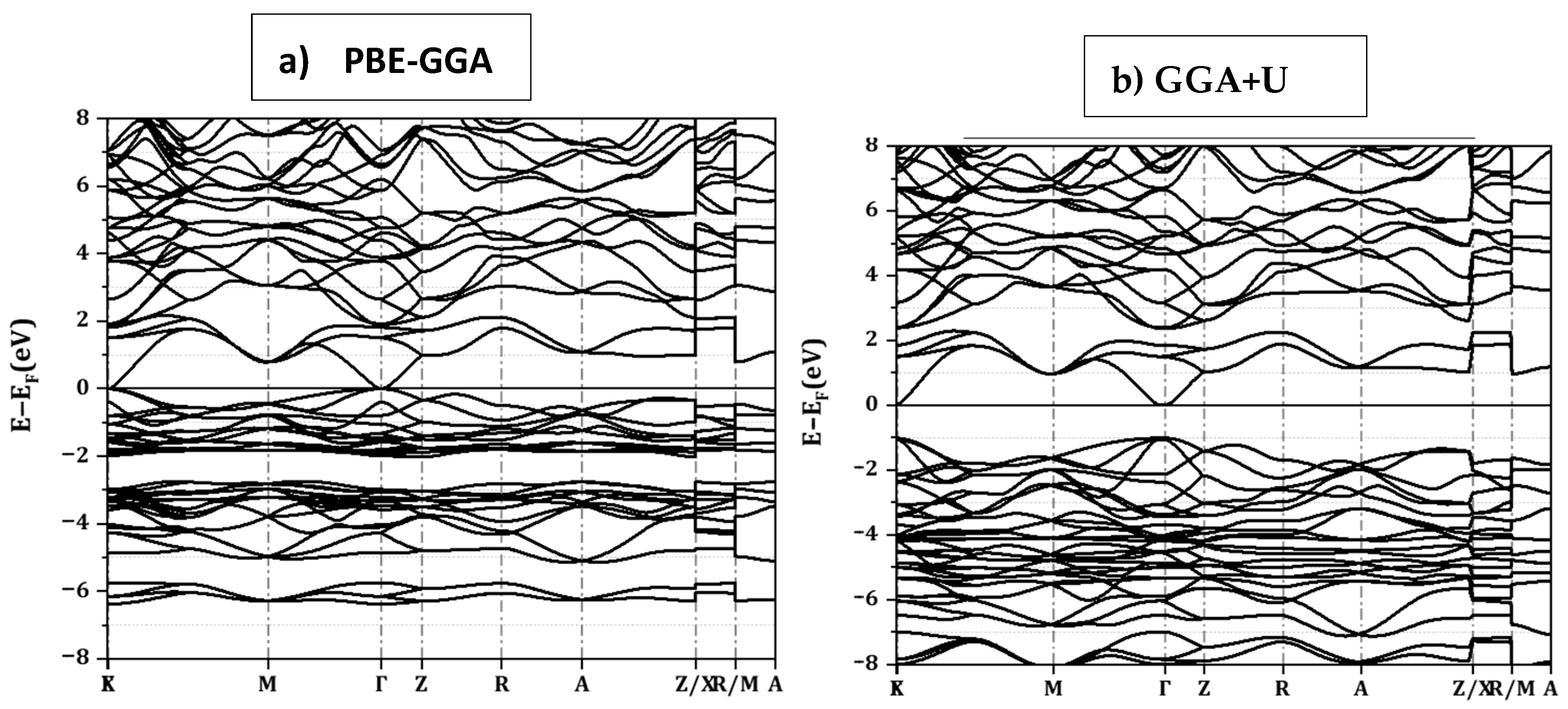

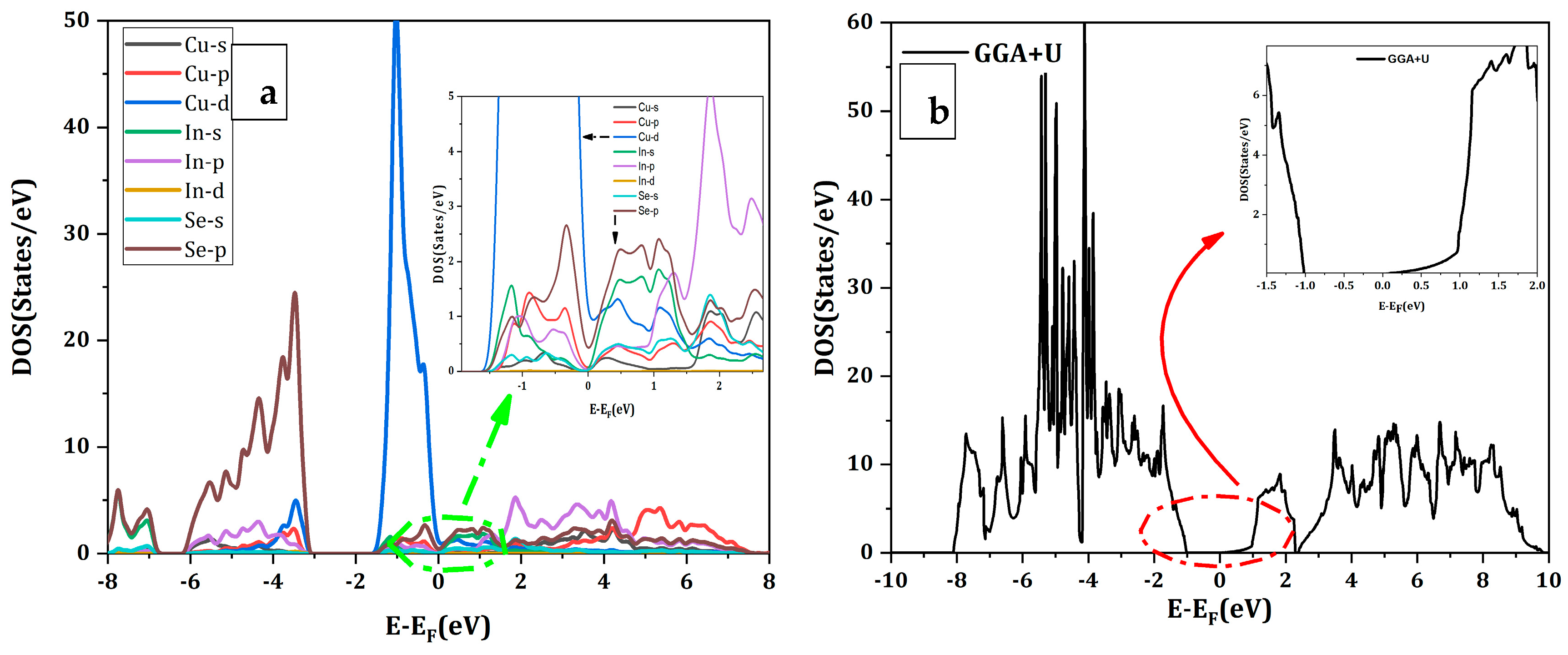

3.3. Band Structure and Density of States of CuInSe2 Using GGA

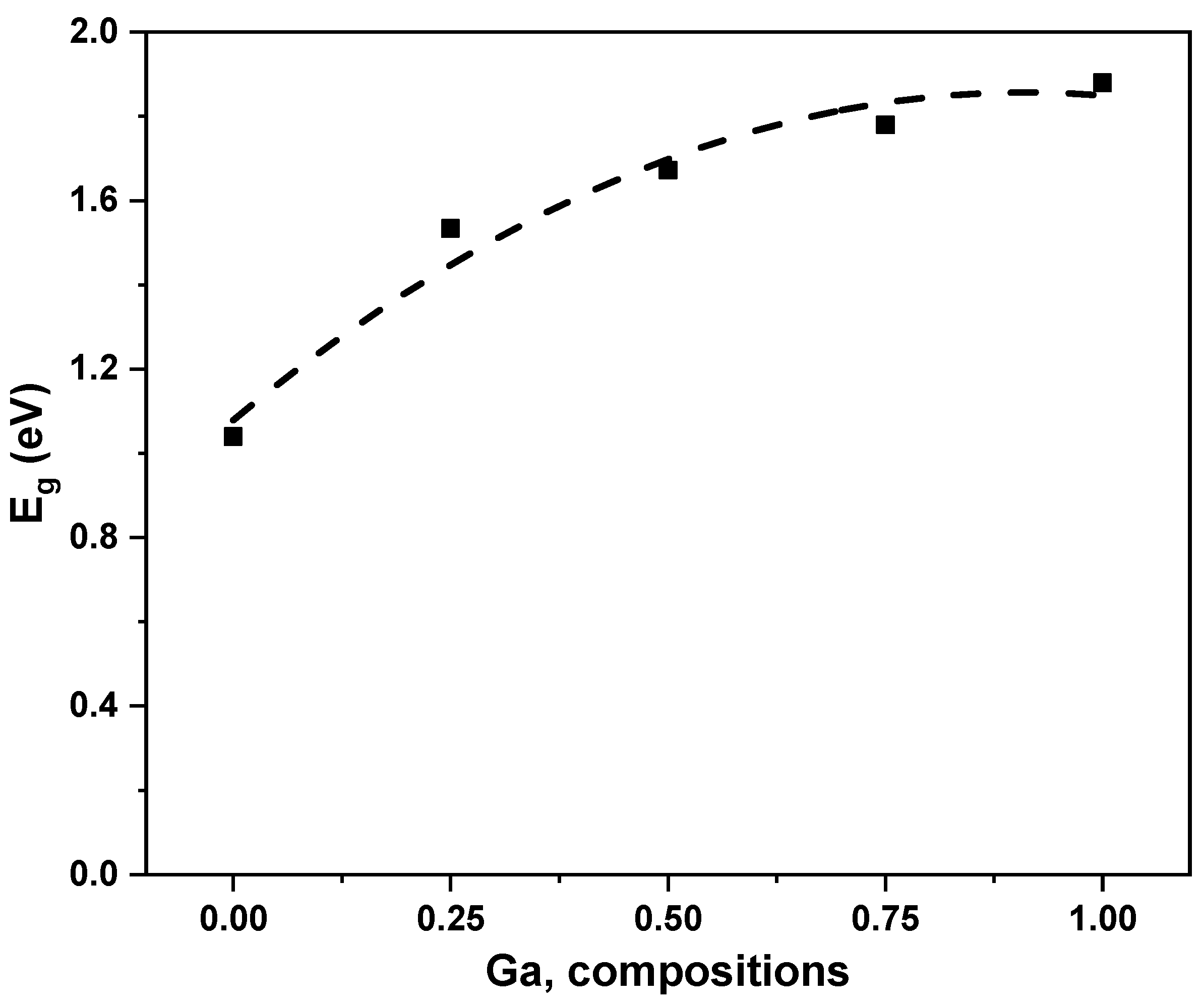

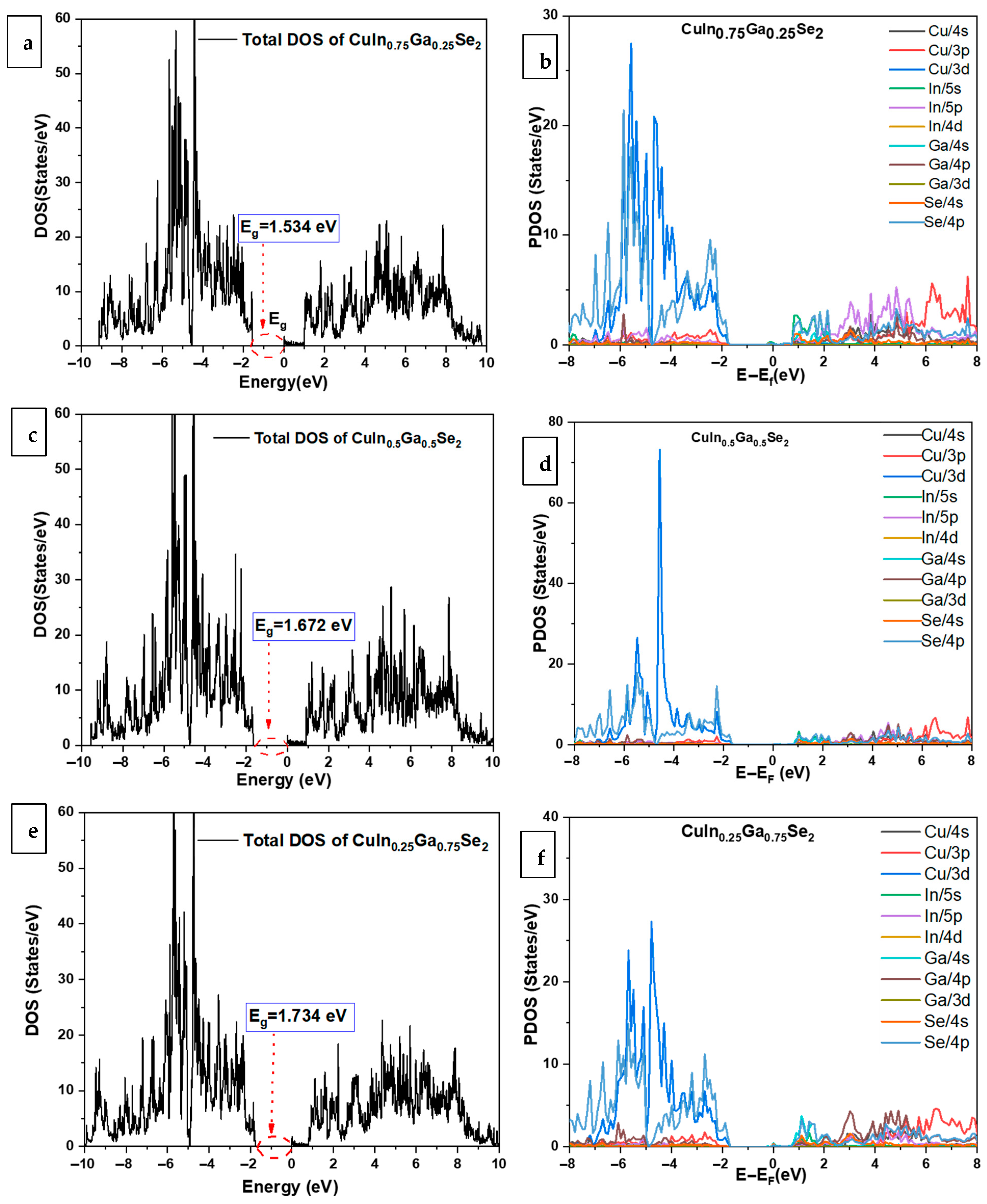

3.4. Band Structure and Densities of States of CuIn1−xGaxSe2 Compounds Using GGA+U

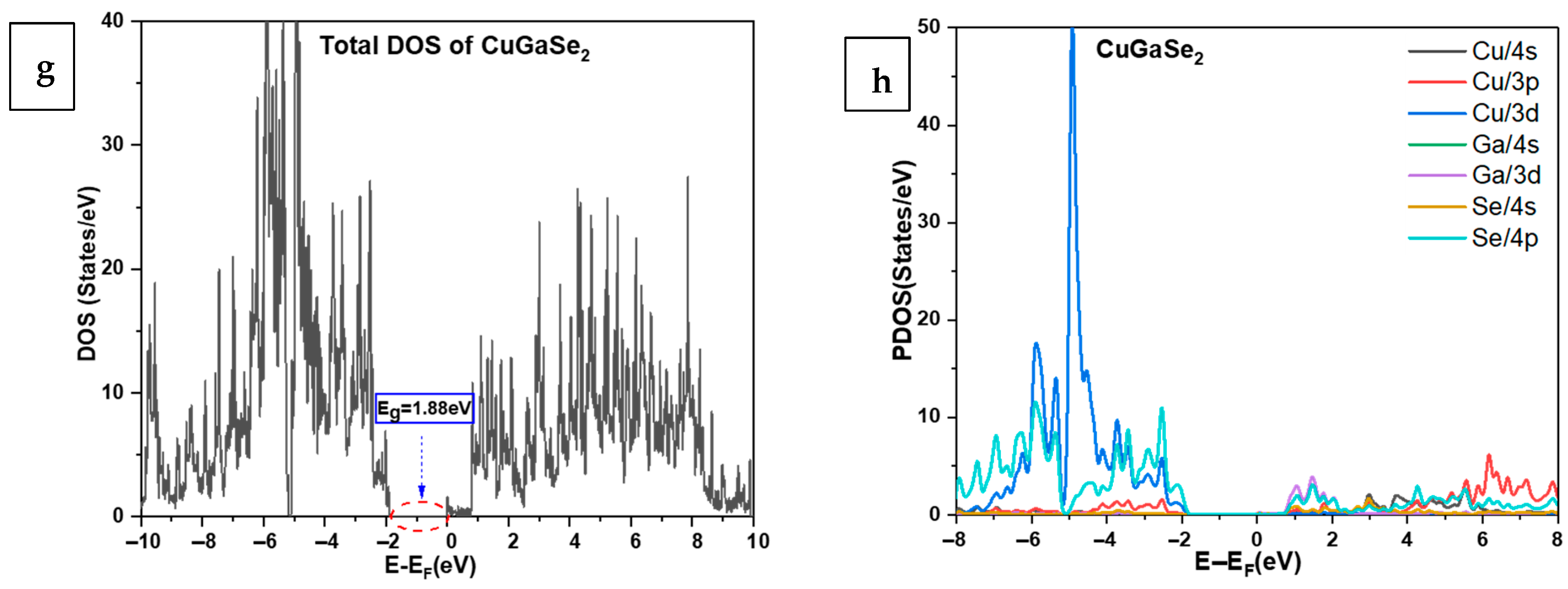

3.5. Charge Redistribution Analysis

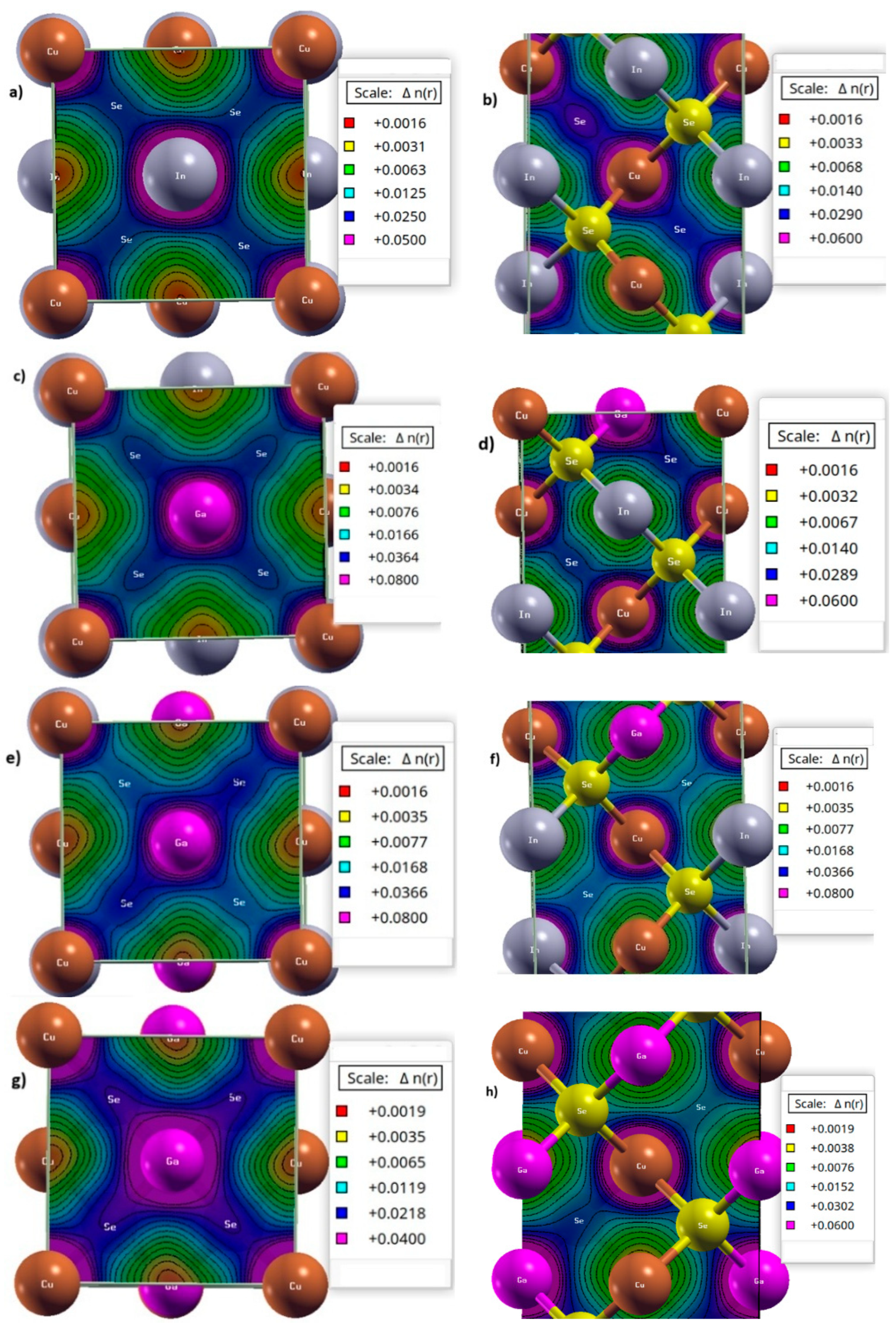

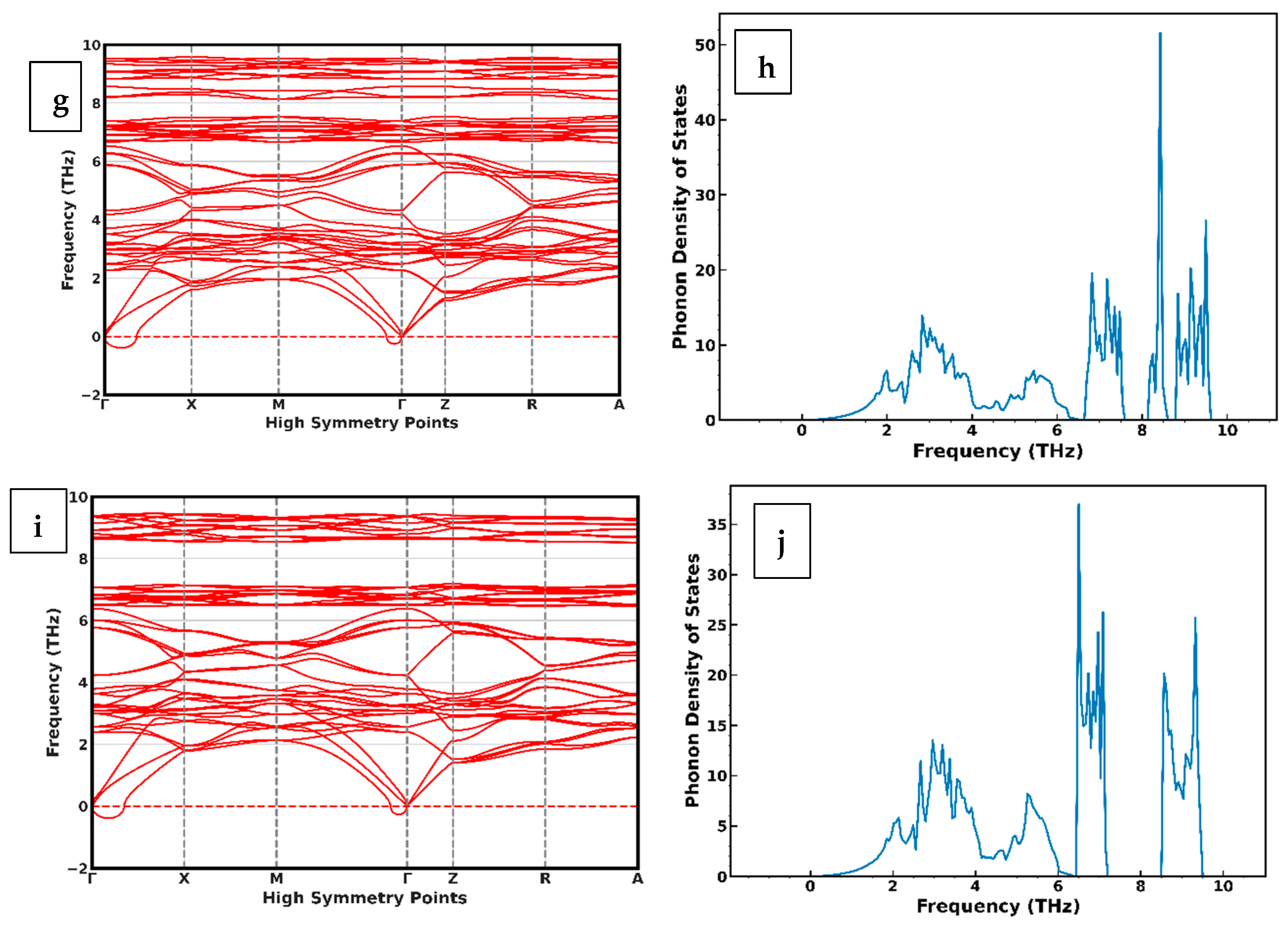

4. Phonon Dispersion of CuIn1−xGaxSe2 Alloys

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pekez, J.; Radovanovc, L.; Desnica, E.; Lambic, M. The increase of exploitability of renewable energy sources. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2016, 11, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.D.; Ebong, A.U. A review of thin film solar cell technologies and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.; Wen, J.; Zhao, Y. Numerical simulation of CuInSe2 solar cells using wxAMPS software. Chin. J. Phys. 2022, 76, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujam, J.; Singh, U.P. Copper indium gallium selenide based solar cells—A review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P.; Hariskos, D.; Lotter, E.; Paetel, S.; Wuerz, R.; Menner, R. New world record efficiency for Cu(In, Ga)Se2 thin-film solar cells beyond 20%. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2011, 19, 894–897. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, T.; Maeda, T. Characteristics of chemical bonds in CuInSe2 and its thin film deposition processes used to fabricate solar cells. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 50, 05FA02. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, J.L.; Tell, B.; Kasper, H.M.; Schiavone, L.M. p−d Hybridization of the Valence Bands of I-III-VI2 Compounds. Phys. Rev. B 1972, 5, 5003. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, J.L.; Tell, B.; Kasper, H.M.; Schiavone, L.M. Electronic Structure of AgInSe2 and CuInSe2. Phys. Rev. B 1973, 7, 4485. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, J.E.; Zunger, A. Theory of the band-gap anomaly in ABC2 chalcopyrite semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1984, 29, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts, V.; Herberholz, R.; Walter, T.; Schock, H.W. Device characteristics of In-rich CuInSe2-based solar cells. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 1997, 30, 2156–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Regmi, G.; Ashok, A.; Chawla, P.; Semalti, P.; Velumani, S.; Sharma, S.N.; Castaneda, H. Perspectives of chalcopyrite-based CIGSe thin-film solar cell: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 7286–7314. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, F.; Blaha, P. Accurate Band Gaps of Semiconductors and Insulators with a Semilocal Exchange-Correlation Potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 226401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, M.; Hong, C.; Yoon, Y.; An, H.; Lee, D.; Jeong, W.; Yoo, D.; Kang, Y.; Youn, Y. A band-gap database for semiconducting inorganic materials calculated with hybrid functional. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Persson, C. Band structure and optical properties of CuInSe2. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 894, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjab, M.; Ibrir, M.; Berrah, S.; Abid, H.; Saeed, M.A. Structural, electronic and optical properties for chalcopyrite semiconducting materials: Ab-initio computational study. Opt.-Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2018, 169, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. First-principles Calculations on Electronic and Elastic Properties of CuInS2 and CuInSe2 at Ambient Pressure. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Management, Education, Information and Control (MEICI 2017), Shenyang, China, 15–17 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amudhavalli, A.; Rajeswarapalanichamy, R.; Padmavathy, R.; Manikandan, M.; Santhosh, M.; Iyakutti, K. Electronic structure, elastic, optical and thermal properties of chalcopyrite CuBY2 (B = In, Ga, In0.5 Ga0.5; Y = S, Se, Te) solar cell compounds. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 101790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Chen, L.; Sun, Q.Q.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, D.W. Hybrid density functional theory study of Cu(In1−xGax)Se2 band structure for solar cell application. AIP Adv. 2014, 4, 087118. [Google Scholar]

- Belhadj, M.; Tadjer, A.; Abbar, B.; Bousahla, Z.; Bouhafs, B.; Aourag, H. Structural, electronic and optical calculations of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 ternary chalcopyrites. Phys. Status Solidi 2004, 241, 2516. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, A.; Gupta, V.; Arora, C.M.; Dashora, A.; Ahuja, B.L. Ahuja: Electronic structure and optical properties of CuGaS2 and CuInS2 solar materials. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 1481. [Google Scholar]

- Brik, M.G. Electronic, optical, and elastic properties of CuXS2 (X = Al, Ga, In) and AgGaS2 semiconductors from first principles calculations. Phys. Status Solidi C 2011, 8, 2582–2584. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, I.; Vidal, J.; Wahnon, P.; Reining, L.; Botti, S. First-principles study of the band structure and optical absorption of CuGaS2. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 085145. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Thangavel, R.; Rajagopalan, M. Electronic and optical modeling of solar cell compound CuXY2 (X = In, Ga; Y = S, Se, Te), first-principles study via Tran-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson exchange potential approach. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 1710. [Google Scholar]

- Giannozzi, P.; Baroni, S.; Bonini, N.; Calandra, M.; Car, R.; Cavazzoni, C.; Ceresoli, D.; Chiarotti, D.L.; Cococcioni, M.; Dabo, I.; et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A Modular and Open-Source Software Project for Quantum Simulations of Materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 395502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, J.E.; Zunger, A. Electronic structure of the ternary chalcopyrite semiconductors CuAls2, CuGaS2, CuInS2, CuAlSe2, CuGaSe2, and CuInSe2. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 28, 5822–5847. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.M.; Structure, E. Basic Theory and Practical Methods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perdew, J.P.; Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandouzi, M.; Alshammari, A.S.; Bouzidi, M.; Khan, Z.R.; Mohamed, M.; Nasrallah, T.B. DFT study of structural optoelectronic and thermoelectric properties of CuNiO ferromagnetic alloys. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 075936. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Corso, A. Elastic constants of beryllium: A first-principles investigation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2016, 28, 075401. [Google Scholar]

- Malica, C.; Dal Corso, A. Quasi-harmonic temperature dependent elastic constants: Applications to Silicon, Aluminum, and Silver. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 315902. [Google Scholar]

- Murnaghan, F.D. The compressibility of media under extreme pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1944, 30, 244–247. [Google Scholar]

- Vegard, L. The constitution of mixed crystals and the space occupied by atoms. Z. Für Phys. 1921, 5, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Verma, A.S.; Bhandari, R.; Jindal, V.K. Ab initio studies of structural, elastic and thermal properties of copper indium dichalcogenides (CuInX2: X = S, Se, Te). Comput. Mater. Sci. 2014, 86, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Domain, C.; Laribi, S.; Taunier, S.; Guillemoles, J.F. Ab initio calculation of intrinsic point defects in CuInSe2. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2003, 64, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluengphon, P.; Bovornratanaraks, T.; Vannarat, S.; Yoode, K.; Ruffolo, D.; Pinsook, U. Ab initio calculation of high pressure phases and electronic properties of CuInSe2. Solid State Commun. 2012, 152, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramohana, M.; Velumani, S.; Venkatachalam, T. Band structure calculations of Cu(In1−xGax)Se2. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2010, 174, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, M.; Kannan, M.D.; Jayakumar, S.; Balasundaraprabhu, R.; Muthukumarasamy, N.; Nandakumar, A.K. CuInxGa1-xSe2 thin films prepared by electron beam evaporation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 517–575. [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata, S.; Chichibu, S.; Isomura, S. Room-Temperature Photoreflectance of CuAlxGa1-xSe2 Alloys. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 36, 7160–7161. [Google Scholar]

- Łazewski, J.; Neumann, H.; Jochym, P.T.; Parlinski, K. Ab initio elasticity of chalcopyrites. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 3789–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.S.; Sharma, S.; Bhandari, R.; Srkar, B.K.; Jindal, V.K. Elastic properties of chalcopyrite structured solids. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 416–420. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Found. Crystallogr. 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Zhou, B.-C.; Wolverton, C. First-principles study of crystal structure and stability of T1 precipitates in Al-Li-Cu alloys. Acta Mater. 2018, 145, 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhat, F.; Coudert, F.X. Necessary and Sufficient Elastic Stability Conditions in Various Crystal Systems. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 224104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The elastic behavior of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. A 1952, 65, 349. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.-W.; An, L. First-principles determination of pressure-induced structure, anisotropic elasticity and ideal strengths of CuInS2 and CuInSe2. Solid State Commun. 2020, 316–317, 113952. [Google Scholar]

- Himmetoglu, B.; Floris, A.; De Gironcoli, S.; Cococcioni, M. Hubbard-corrected DFT energy functionals: The LDA+U description of correlated systems. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2014, 114, 14–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cococcioni, M. The LDA+U approach: A simple Hubbard correction for correlated ground states. Correl. Electrons Models Mater. Model. Simul. 2012, 2. Available online: https://www.cond-mat.de/events/correl12/manuscripts/cococcioni.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Gandouzi, M.; Alshammari, A.S.; Khan, Z.R.; Bouzidi, M. DFT study of the structural and optoelectronic properties of Cd1−xAgxS half metallic alloys. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 129, 105794. [Google Scholar]

- Gandouzi, M.; Khan, Z.R.; Alshammari, A.S. Theoretical and experimental investigations of the structural and optoelectronic properties of Zn1−xCdxO alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 156, 346–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gandouzi, M.; Alshammary, H.; Khan, Z.R.; Alshammari, A.S.; Hedhili, F. Experimental and DFT studies of structural and optoelectronic properties of CdS, Zn doped CdS, and (Zn-Ni) co-doping CdS nanomaterials. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 065935. [Google Scholar]

- Bruus, H.; Flensberg, K. Introduction to Many-Body Quantum Theory in Condensed Matter Physics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 152–182. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Ramadugu, S.K.; Maso, S.E. Surface-Specific DFT + U Approach Applied to α-Fe2O3(0001). J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Knotek, M.L.; Feibelman, P.J. Ion Desorption by Core-Hole Auger Decay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Maxisch, T.; Ceder, G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+U framework. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 195107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.W.; Lee, K.; Cococcioni, M.; Smit, B.; Neaton, J.B. First-principles Hubbard U approach for small molecule binding in metal-organic frameworks. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 174104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erhart, P.; Albe, K.; Klein, A. First-principles study of intrinsic point defects in ZnO: Role of band structure, volume relaxation, and finite-size effects. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 205203. [Google Scholar]

- Janotti, A.; Segev, D.; de Walle, C.G.V. Effects of cation d states on the structural and electronic properties of III-nitride and II-oxide wide-band-gap semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 045202. [Google Scholar]

- Setyawan, W.; Gaume, R.M.; Lam, S.; Feigelson, R.S.; Curtarolo, S. High-Throughput Combinatorial Database of Electronic Band Structures for Inorganic Scintillator Materials. ACS Comb. Sci. 2011, 13, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloeckler, M.; Sites, J.R. Band-gap grading in Cu(In,Ga)Se2 solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2005, 66, 1891–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Albin, D.S.; Carapella, J.J.; Tuttle, J.R.; Noufi, R. The effect of copper vacancies on the optical bowing of chalcopyrite Cu(In,Ga)Se2 alloys. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1992, 228, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Bouraoui, A.; Berredjem, Y.; Ain-Souya, A.; Drici, A.; Amara, A.; Kanzari, M.; Akkari, F.C.H.F.A.; Khemiri, N.; Bernede, J.C. Investigation of CuIn1-xGaxSe2 thin films co-evaporated from two metal sources for photovoltaic solar cells. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 2017, 19, 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco, T.; Quintero, M.; Rincon, C. Variation of the energy gap with composition in AI BIII C2 VI chalcopyrite-structure alloys. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 1613. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.-H.; Zunger, A. Band offsets and optical bowings of chalcopyrites and Zn-based II–VI alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 1995, 78, 3846–3856. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, J.; Tomlinson, R.D.; Hampshire, M.J. Crystal data for CuInSe2. J. Appl. Cryst. 1973, 6, 414–416. [Google Scholar]

- Giannozzi, P.; de Gironcoli, S.; Pavone, P.; Baroni, S. Ab initio calculation of phonon dispersions in semiconductor. Phys. review. B Condens. Matter 1991, 43, 7231–7242. [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnikov, A.I.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; Nomura, K.-I.; Wu, Z.; Abernathy, D.L.; Huq, A.; Granroth, G.E.; Christe, K.O.; Haiges, R.; Kalia, R.K.; et al. Inelastic Neutron Scattering Study of Phonon Density of States of Iodine Oxides and First-Principles Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 10080−10087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | Lattice Parameters: a = b (Å) − c (Å) | Distortion Parameters | Bulk Modulus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our Work | Experimental Work | Other Work | B (GPa) | ||

| CuInSe2 | 5.869–11.779 | 5.78 d–11.64 d | 5.82 a–11.76 a | 1.00349 | 53.75 |

| CuIn0.75Ga0.25Se2 | 5.813–11.687 | 5.75 e–5.72 c 11.69 e–11.63 c | 5.76 a–5.69 b 11.70 a–11.39 b | 1.00533 | 56.042 |

| CuIn0.5Ga0.5Se2 | 5.772–11.565 | 5.73 e–11.66 e | 5.75 a–5.67 b 11.43 a–11.54 b | 1.00187 | 56.514 |

| CuIn0.25Ga0.75Se2 | 5.716–11.421 | 5.72 e–11.63 e | 5.96 a–5.61 b 11.31 a–11.39 b | 0.9989 | 58.750 |

| CuGaSe2 | 5.669–11.258 | 5.61 e–11.02 e | 5.63 a–11.15 a | 0.9929 | 59.160 |

| Compounds | Formation Energy (eV/atom) |

|---|---|

| CuInSe2 | −1.037 |

| CuIn0.75Ga0.25Se2 | −1.043 |

| CuIn0.5Ga0.5Se2 | −1.043 |

| CuIn0.25Ga0.75Se2 | −0.983 |

| CuGaSe2 | −1.069 |

| CuInSe2 | CuIn0.75Ga 0.25Se2 | CuIn0.5Ga 0.5Se2 | CuIn0.25Ga 0.75Se2 | CuGaSe2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (GPa) | 71.86 | 75.81 | 78.81 | 82.92 | 84.13 |

| (GPa) | 44.85 | 45.41 | 45.90 | 48.42 | 45.62 |

| (GPa) | 45.71 | 46.48 | 46.31 | 47.12 | 47.31 |

| (GPa) | 70.196 | 74.52 | 77.25 | 80.77 | 83.68 |

| (GPa) | 33.67 | 35.31 | 36.50 | 39.10 | 41.29 |

| (GPa) | 31.61 | 33.29 | 38.00 | 39.66 | 41.68 |

| B (GPa) | 53.75 | 56.04 | 56.51 | 58.75 | 59.16 |

| G (GPa) | 22.62 | 24.52 | 26.54 | 28.20 | 32.30 |

| E(GPa) | 59.44 | 64.14 | 68.78 | 73.11 | 81.98 |

| p | 0.314 | 0.307 | 0.296 | 0.292 | 0.269 |

| r | 2.376 | 2.285 | 2.129 | 2.083 | 1.831 |

| 2242.64 | 2341.12 | 2443.56 | 2535.14 | 2616.61 | |

| 226.95 | 239.18 | 254.80 | 266.57 | 278.63 |

| Band Gap | Calculated Eg (eV) | Other Theoretical Work [18] | Experimental Eg (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CuInSe2 | 1.04 | 1.205 | 1.04 [8,59] |

| CuIn0.75Ga0.25Se2 | 1.534 | 1.275 | -- |

| CuIn0.5Ga0. 5Se2 | 1.672 | 1.416 | -- |

| CuIn0.25Ga0. 75Se2 | 1.78 | 1.445 | -- |

| CuGaSe2 | 1.88 | 1.568 | 1.67 [38,59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gandouzi, M.; Alshammari, O.H.; Hedhili, F.; Albaqawi, H.S.; Al-Shammari, N.A.; Alshammari, M.F.; Tanaka, T. First-Principles Investigation of Structural, Electronic, and Elastic Properties of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 Chalcopyrite Alloys Using GGA+U. Symmetry 2026, 18, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010025

Gandouzi M, Alshammari OH, Hedhili F, Albaqawi HS, Al-Shammari NA, Alshammari MF, Tanaka T. First-Principles Investigation of Structural, Electronic, and Elastic Properties of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 Chalcopyrite Alloys Using GGA+U. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleGandouzi, Mohamed, Owaid H. Alshammari, Fekhra Hedhili, Hissah Saedoon Albaqawi, Nwuyer A. Al-Shammari, Manal F. Alshammari, and Takuo Tanaka. 2026. "First-Principles Investigation of Structural, Electronic, and Elastic Properties of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 Chalcopyrite Alloys Using GGA+U" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010025

APA StyleGandouzi, M., Alshammari, O. H., Hedhili, F., Albaqawi, H. S., Al-Shammari, N. A., Alshammari, M. F., & Tanaka, T. (2026). First-Principles Investigation of Structural, Electronic, and Elastic Properties of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 Chalcopyrite Alloys Using GGA+U. Symmetry, 18(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010025