Numerical Analysis of the Relationship Between Vanadium Flow Rate, State of Charge, and Vanadium Ion Uniformity

Abstract

1. Introduction

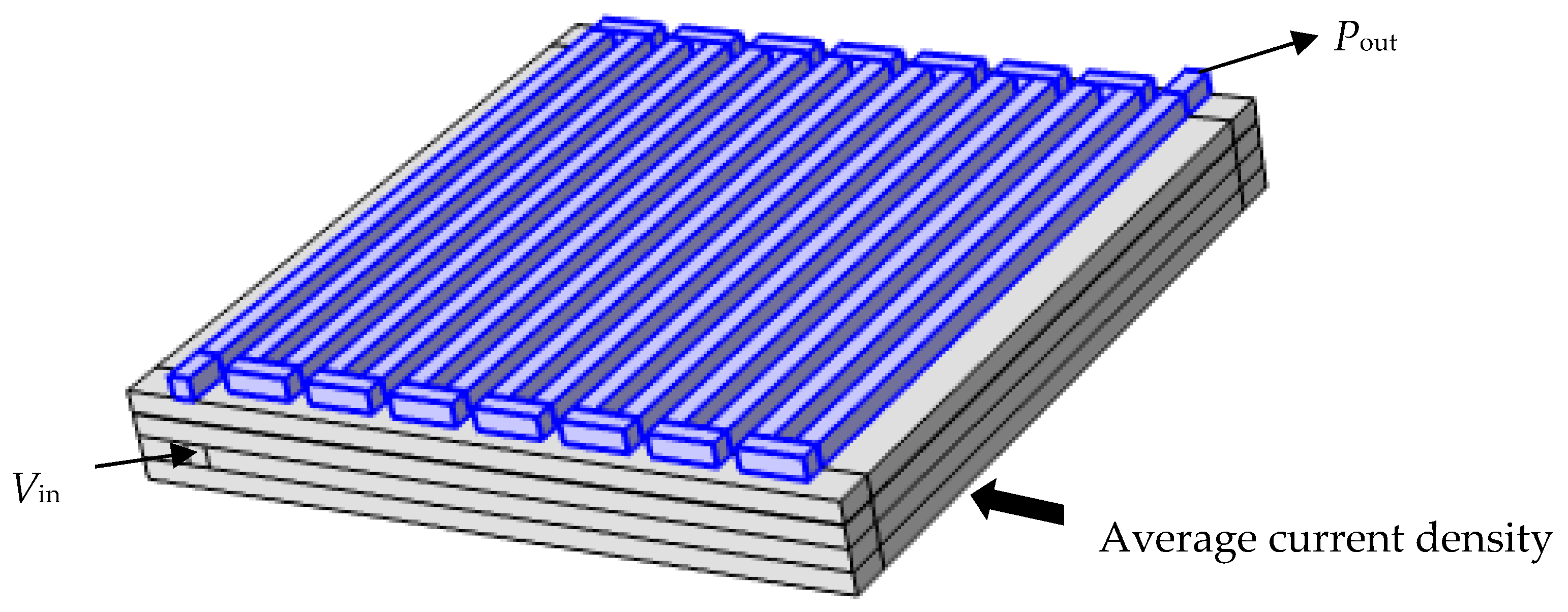

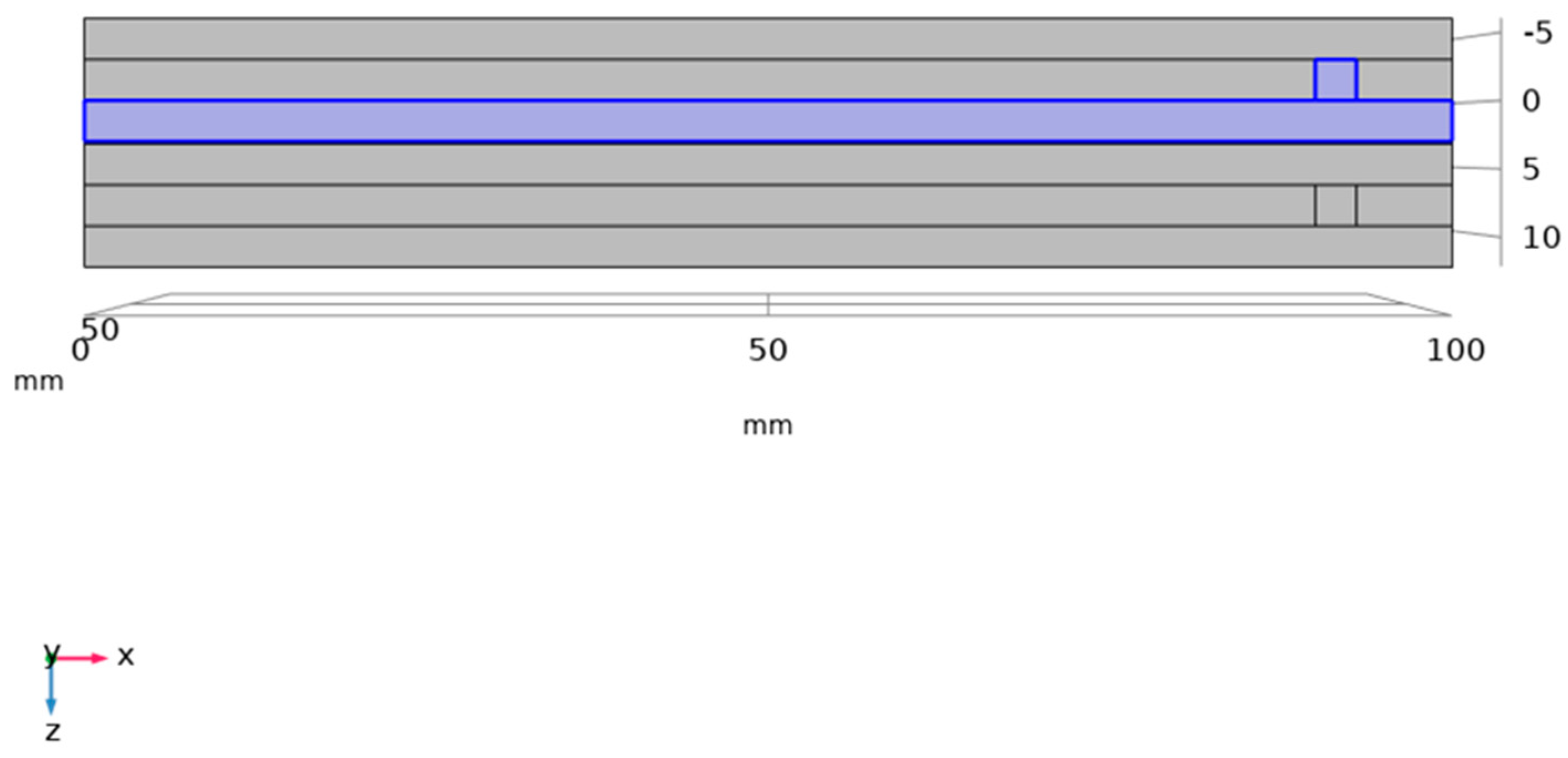

2. Model

2.1. Electrochemical Reaction Mechanism and Assumptions

- (1)

- Isothermal conditions apply throughout the entire operating process of the VRFB [12].

- (2)

- The electrolyte is treated as an incompressible fluid [13].

- (3)

- Changes in electrolyte volume due to water permeation or resistance to water flow through the membrane are neglected [14].

- (4)

- (5)

- Assume the electrolyte is a dilute solution [11].

- (6)

- (7)

- Except for hydrogen ions, other ions are considered unable to pass through the ion exchange membrane [19].

- (8)

2.2. Control Equations and Kinetic Equations

2.3. Boundary Conditions

2.4. Performance Parameters

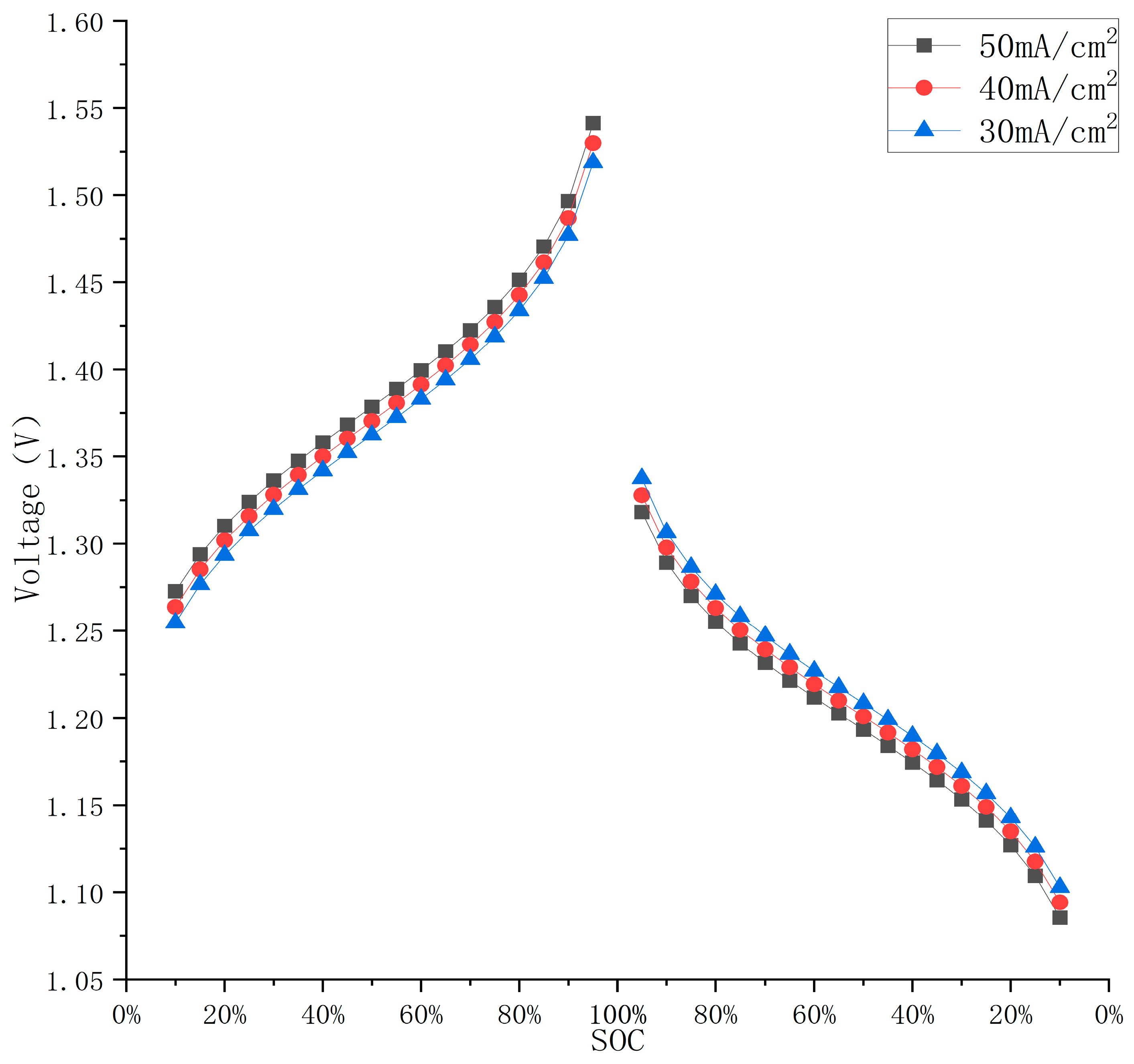

2.5. Numerical Details and Charge–Discharge Cell Voltage Simulation Testing

3. Results and Discussion

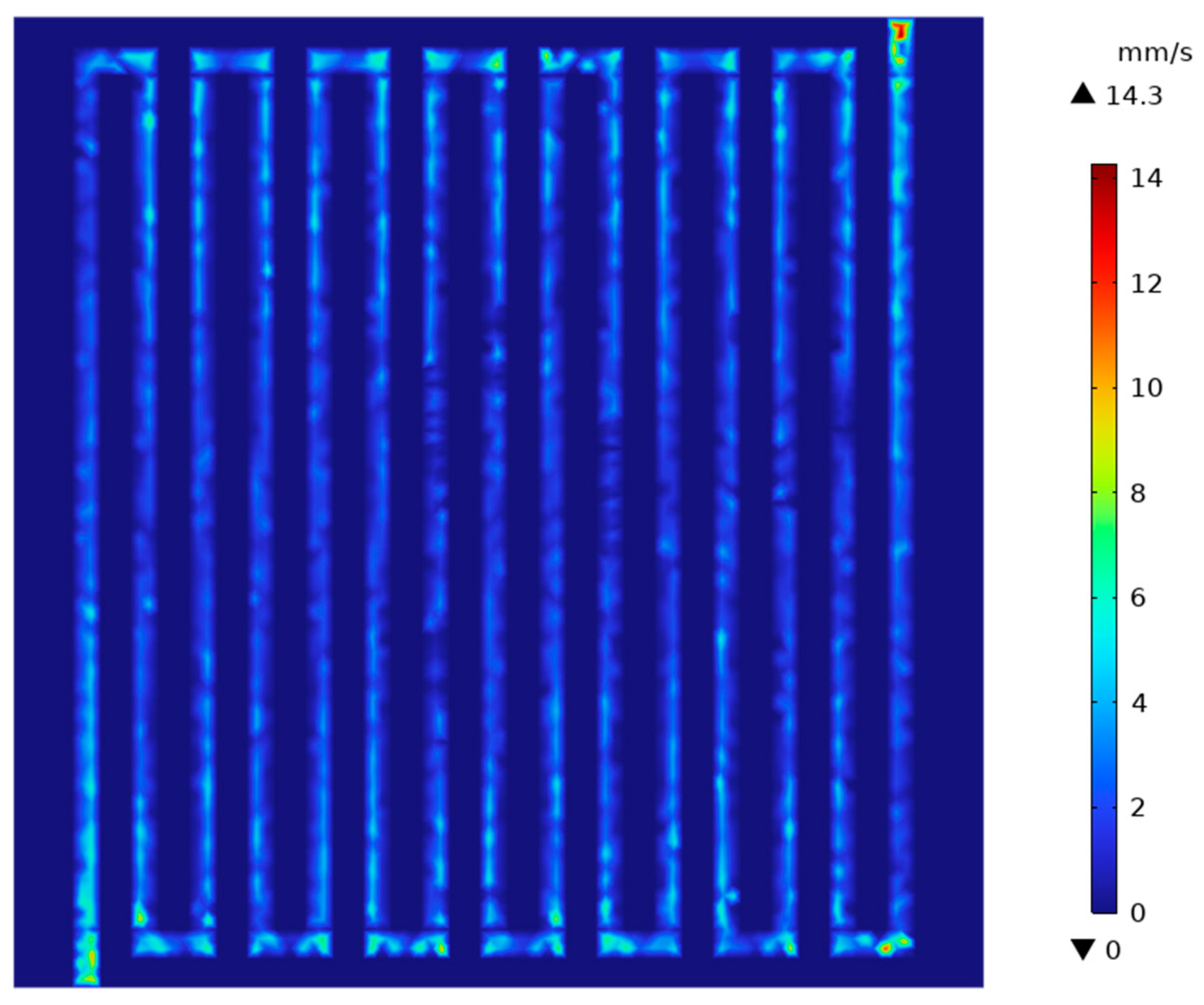

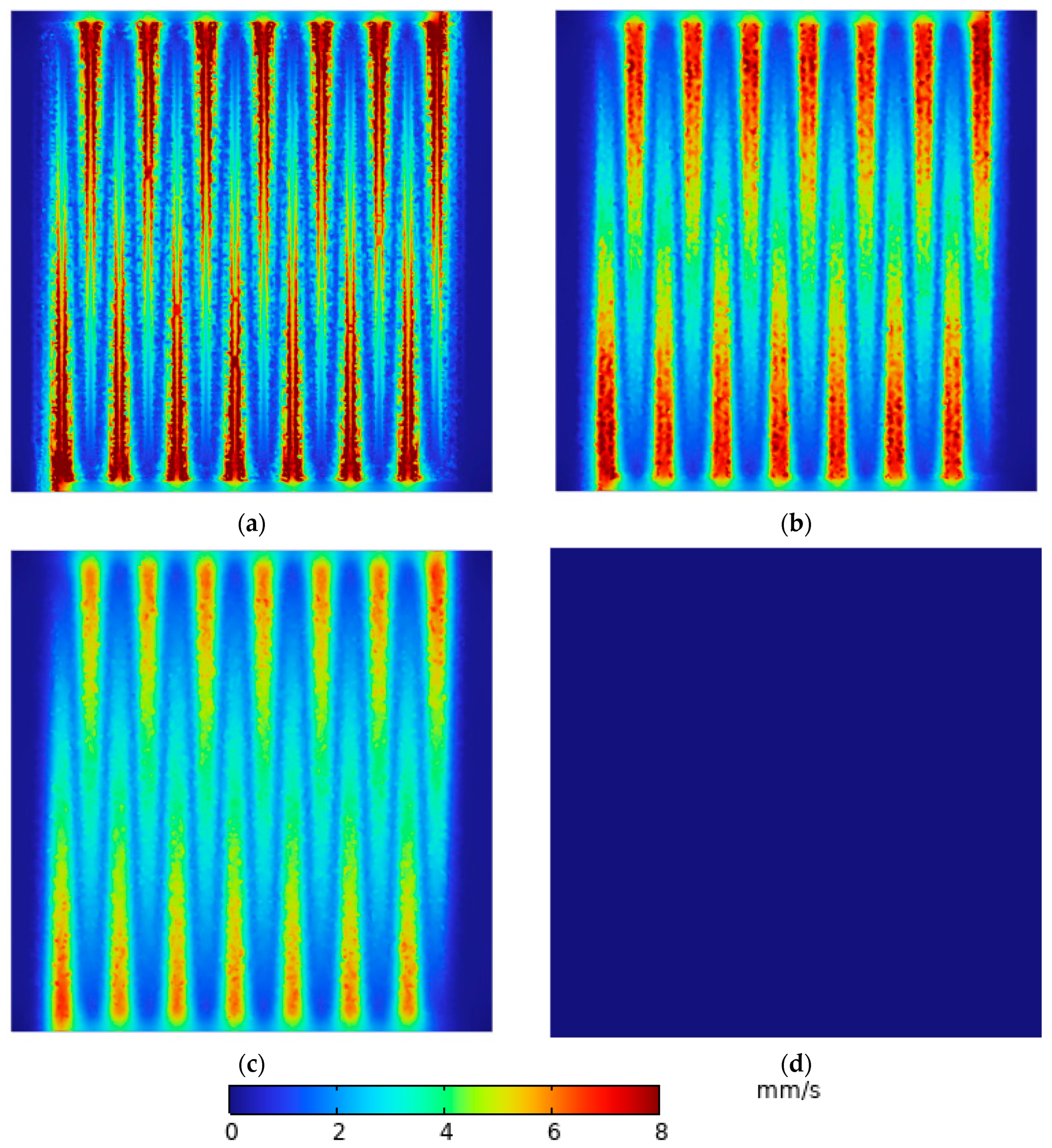

3.1. Velocity Distribution of Electrolyte Under Porous Carbon Felt

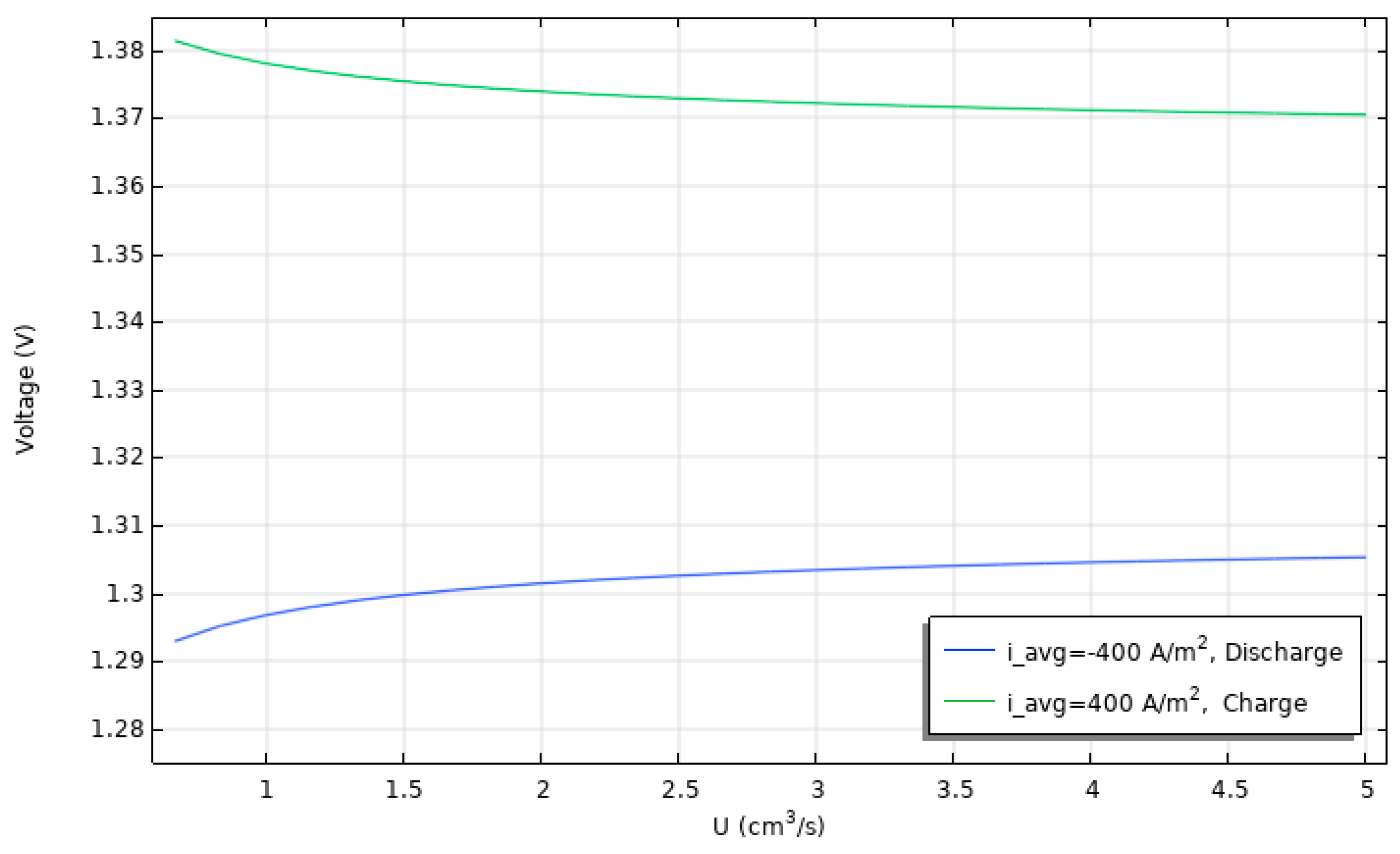

3.2. Effect of Current on Battery Charge/Discharge Cell Voltage

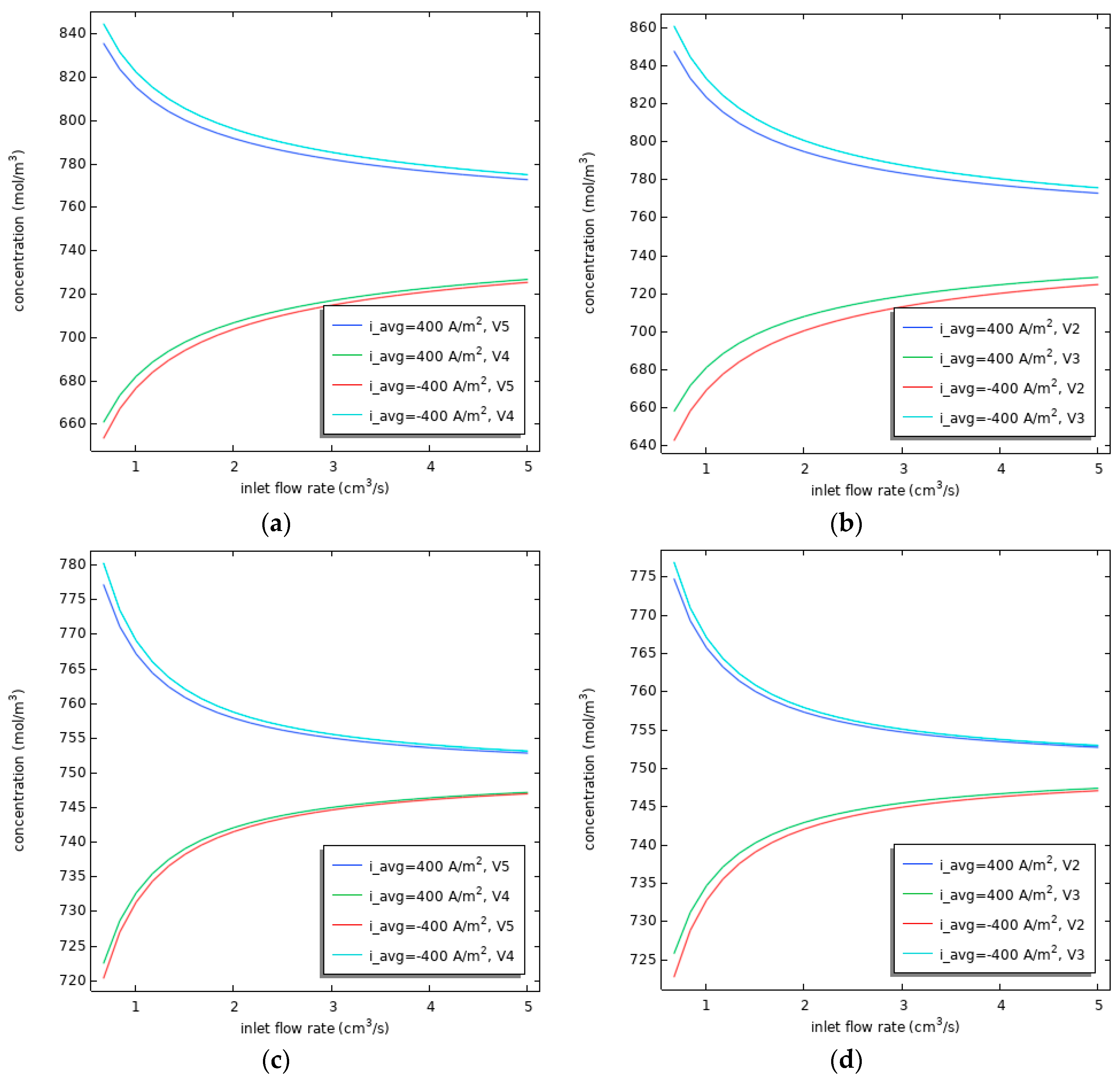

3.3. Effect of Flow Rate on Vanadium Ion Concentration

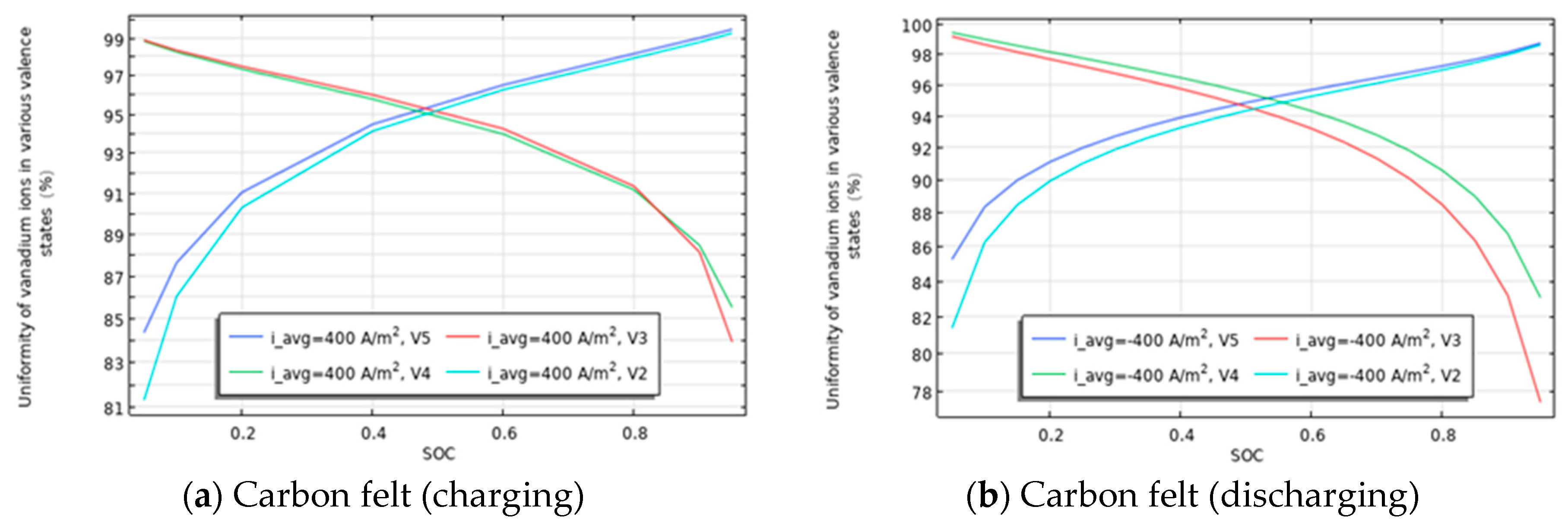

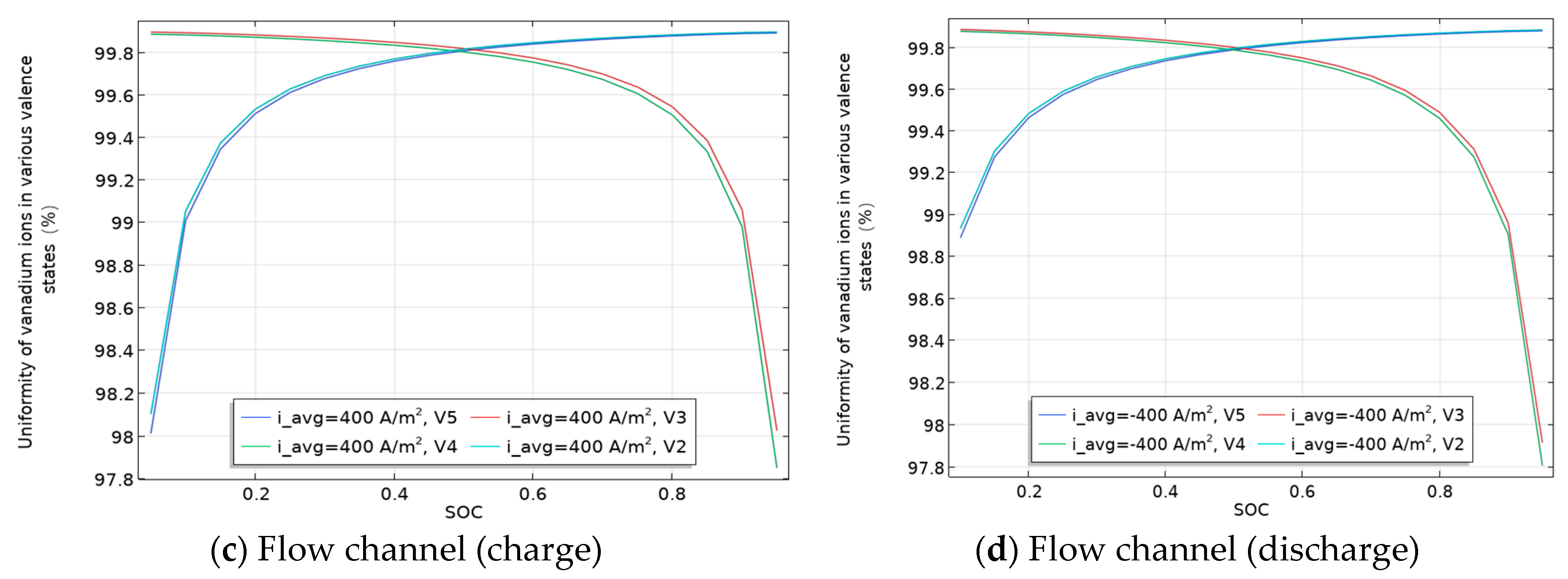

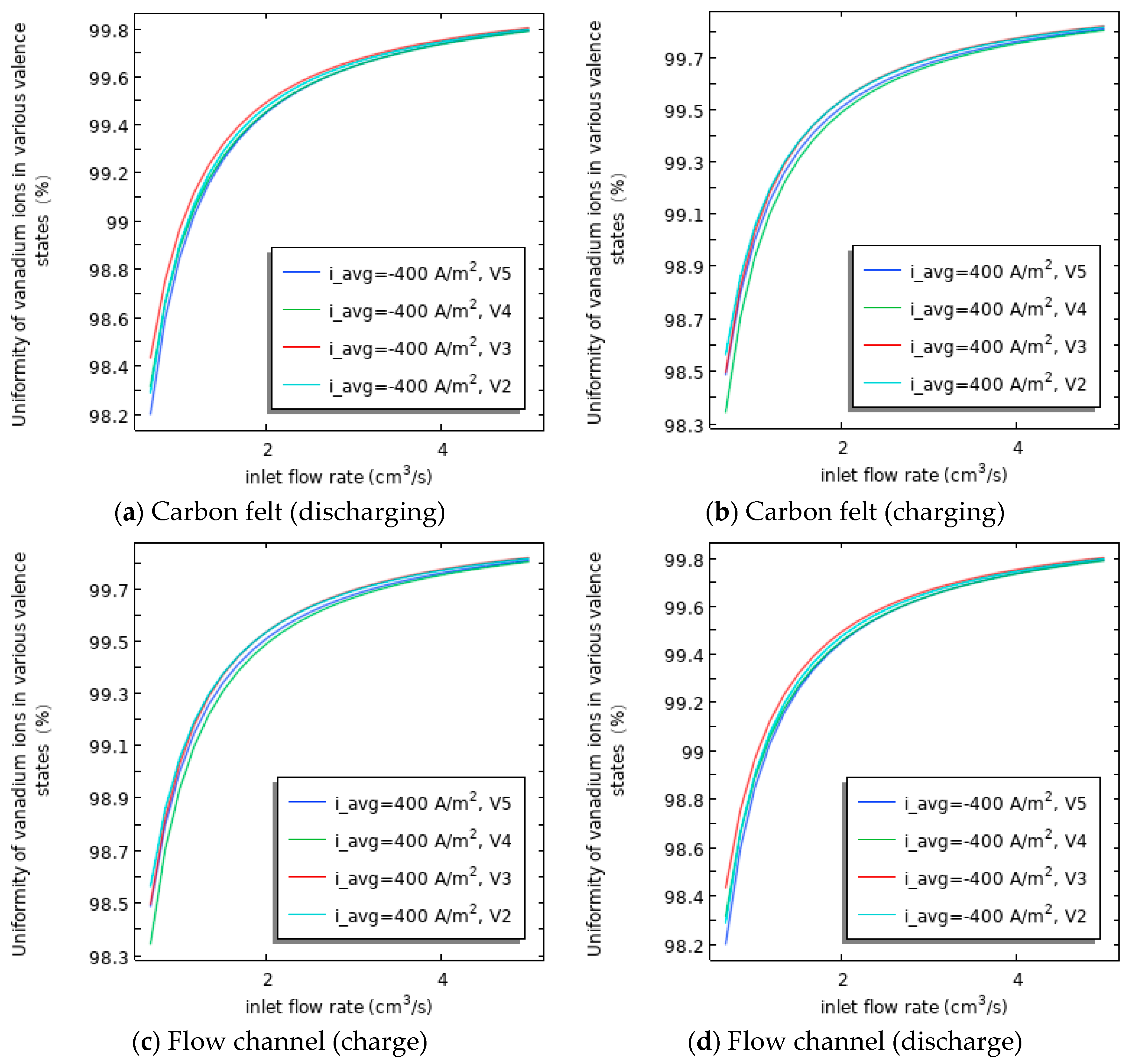

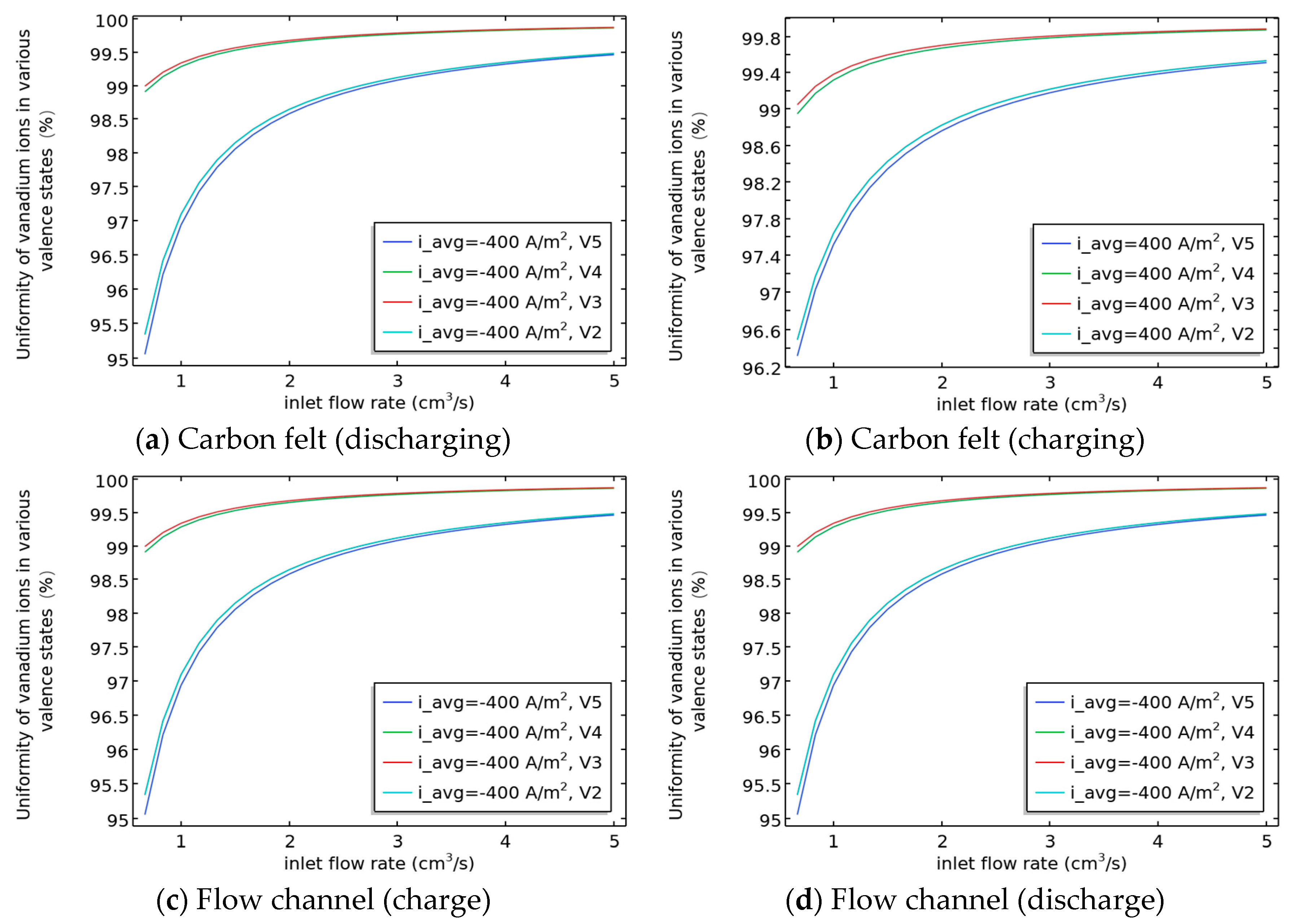

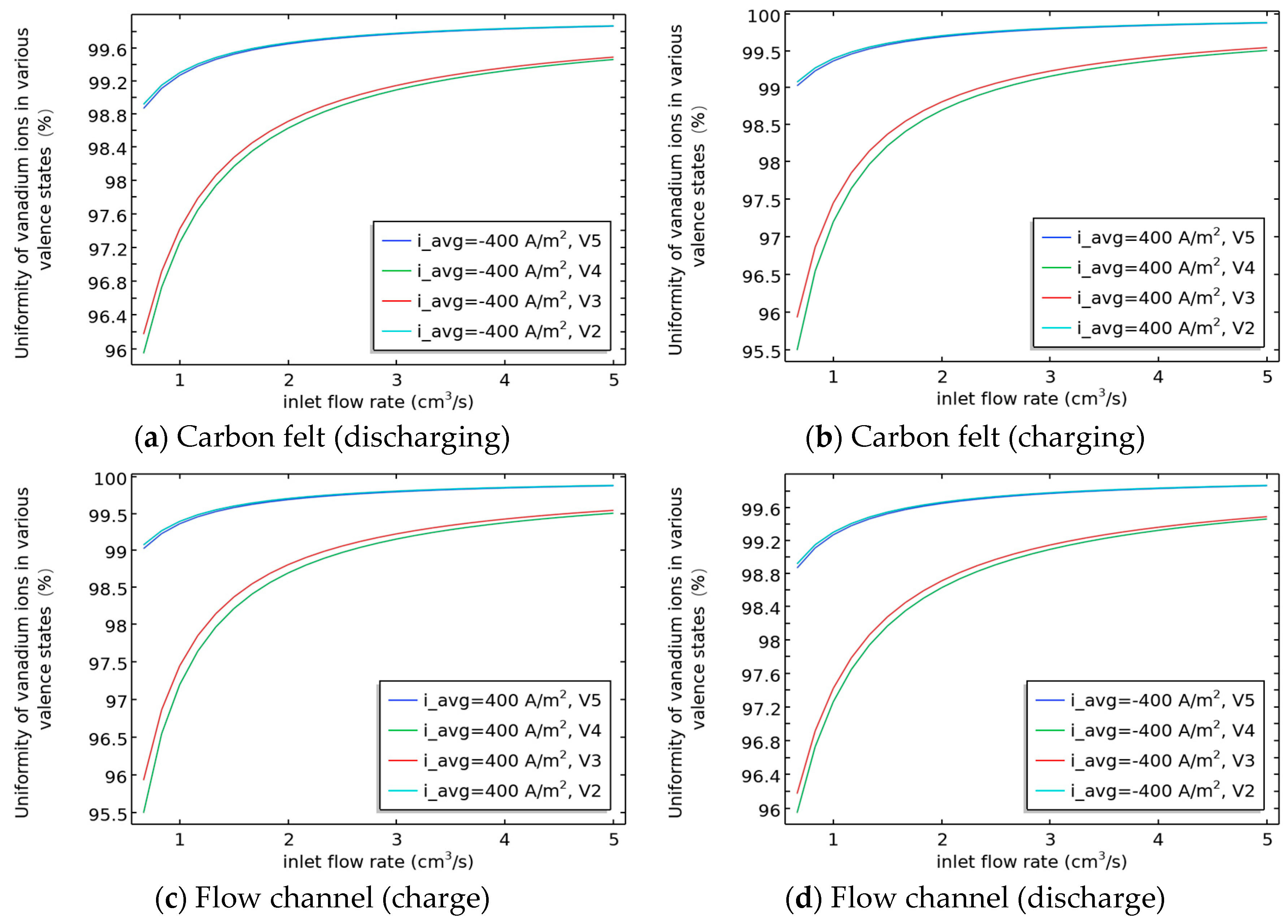

3.4. Relationship Between the Uniformity of Various Valence States of Vanadium Ions in Flow Channels and Carbon Felt and SOC/Flow Velocity

4. Outlook and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Esan, O.C.; Shi, X.; Pan, Z.; Huo, X.; An, L.; Zhao, T.S. Modeling and Simulation of Flow Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2000758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, E.B.; Abdullah, M.; Odoi-Yorke, F.; Ameen, A.; Chowdhury, P.; Raza, M.A.; Rashid, F.L.; Hussein, A.K. A state-of-the-art review of electrolyte systems for vanadium redox flow battery ? status of the technology, and future research directions. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Progress and perspectives of flow battery technologies. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2019, 18, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, B.; Weber, L.S.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M.; Bao, J.; Meng, K. Thermal Modelling and Simulation Studies of Containerised Vanadium Flow Battery Systems. Batteries 2023, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Al-Fetlawi, H.; Walsh, F.C. Dynamic modelling of hydrogen evolution effects in the all-vanadium redox flow battery. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 1125–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Watt-Smith, M.J.; Walsh, F.C. A dynamic performance model for redox-flow batteries involving soluble species. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 8087–8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J. A simple model for the vanadium redox battery. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 6827–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, S.; Zhang, H.; Su, Y. Finite element-based analysis of composite serpentine flow channel 3D modeling of vanadium redox flow battery. Int. J. Green Energy 2022, 22, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noto, V.; Vezzù, K.; Crivellaro, G.; Pagot, G.; Sun, C.; Meda, L.; Rutkowska, I.; Kulesza, P.; Zawodzinski, T. A general electrochemical formalism for vanadium redox flow batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 408, 139937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, L. Novel electrolyte design for high-efficiency vanadium redox flow batteries with enhanced 3.0 M V3+stability at low temperatures. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 164293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, J.; Feng, J. Research progress in preparation of electrolyte for all-vanadium redox flow battery. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 118, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Deng, Y.; Yang, W.; Ye, M.; Jiao, Y.; Xu, Q. A novel rotary serpentine flow field with improved electrolyte penetration and species distribution for vanadium redox flow battery. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 361, 137089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krowne, C. Fluid Physics Impacting Vanadium and Other Redox Flow Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 060517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Jiao, Y.; Tang, X.; Yang, W.; Ye, M.; Xu, Q. Blocked serpentine flow field with enhanced species transport and improved flow distribution for vanadium redox flow battery. J. Energy Storage 2021, 35, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf Gandomi, Y.; Aaron, D.S.; Mench, M.M. Coupled Membrane Transport Parameters for Ionic Species in All-Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 218, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaggi, M.; Gambaro, C.; Casalegno, A.; Zago, M. Development of innovative flow fields in a vanadium redox flow battery: Design of channel obstructions with the aid of 3D computational fluid dynamic model and experimental validation through locally-resolved polarization curves. J. Power Sources 2022, 526, 231155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hikihara, T. A coupled dynamical model of redox flow battery based on chemical reaction, fluid flow, and electrical circuit. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 2008, E91-A, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milshtein, J.D.; Tenny, K.M.; Barton, J.L.; Drake, J.; Darling, R.M.; Brushett, F.R. Quantifying Mass Transfer Rates in Redox Flow Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, E3265–E3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Long, J.; Huang, W.; Xu, W.; Liu, J.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Y. Novel branched sulfonated polyimide membrane with remarkable vanadium permeability resistance and proton selectivity for vanadium redox flow battery application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 8883–8891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, J.; Sethuraman, M.; Roh, S.; Jung, H. Recent developments in sol-gel based polymer electrolyte membranes for vanadium redox flow batteries—A review. Polym. Test. 2020, 89, 106567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.; Kwon, H.; Choi, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Park, H. A numerical study of electrode thickness and porosity effects in all vanadium redox flow batteries. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Zhao, T.S.; An, L.; Zeng, Y.K.; Yan, X.H. A vanadium redox flow battery model incorporating the effect of ion concentrations on ion mobility. Appl. Energy 2015, 158, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krowne, C.M. Nernst Equations and Concentration Chemical Reaction Overpotentials for VRFB Operation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, T.S.; Zhang, C. Effects of SOC-dependent electrolyte viscosity on performance of vanadium redox flow batteries. Appl. Energy 2014, 130, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugach, M.; Parsegov, S.; Gryazina, E.; Bischi, A. Output feedback control of electrolyte flow rate for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. J. Power Sources 2020, 455, 227916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauermoser, M.; Kizilova, N.; Pollet, B.G.; Kjelstrup, S. Flow Field Patterns for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Jayanti, S. Effect of flow field on the performance of an all-vanadium redox flow battery. J. Power Sources 2016, 307, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Yuan, D.; Yu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Ding, M.; Sun, Q.; Jia, C. A Cost-effective Nafion Composite Membrane as an Effective Vanadium-Ion Barrier for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. Chem.-Asian J. 2020, 15, 2357–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Yang, G.; Zhao, S.; Xia, L.; Chu, F.; Tan, Z.a. Battery performance optimization and multi-component transport enhancement of organic flow battery based on channel section reconstruction. Energy 2022, 258, 124757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivona, D.; Messaggi, M.; Baricci, A.; Casalegno, A.; Zago, M. Unravelling the Contribution of Kinetics and Mass Transport Phenomena to Impedance Spectra in Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries: Development and Validation of a 1D Physics-Based Analytical Model. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 110534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, S.; Suzuki, T. Modeling and Simulation of Vanadium Redox Flow Battery with Interdigitated Flow Field for Optimizing Electrode Architecture. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 020553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, S.; Pugach, M.; Parsegov, S.; Vlasov, V.; Ibanez, F.M.; Stevenson, K.J.; Vorobev, P. Dynamic modeling of vanadium redox flow batteries: Practical approaches, their applications and limitations. J. Energy Storage 2023, 57, 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kang, J.; Shu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of storage capacity and energy conversion on the performance of gradient and double-layered porous electrode in all-vanadium redox flow batteries. Energy 2019, 180, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL Multiphysics®, version 6.3; COMSOL AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024.

- Gurieff, N.; Cheung, C.Y.; Timchenko, V.; Menictas, C. Performance enhancing stack geometry concepts for redox flow battery systems with flow through electrodes. J. Energy Storage 2019, 22, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Agarwal, V.; Barnwal, V.K.; Sahu, S.; Singh, A. Optimization of channel and rib dimension in serpentine flow field for vanadium redox flow battery. Energy Storage 2022, 5, e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, B.; Zheng, M.; Luo, Y.; Yu, Z. Serpentine flow field with changing rib width for enhancing electrolyte penetration uniformity in redox flow batteries. J. Energy Storage 2022, 49, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, T.S.; Leung, P.K. Numerical investigations of flow field designs for vanadium redox flow batteries. Appl. Energy 2013, 105, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei-Jelyani, M.; Loghavi, M.M.; Babaiee, M.; Eqra, R. The significance of charge and discharge current densities in the performance of vanadium redox flow battery. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 443, 141922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Tan, L. Control strategy optimization of electrolyte flow rate for all vanadium redox flow battery with consideration of pump. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, B. Numerical analysis of the design optimization obstruction to guide electrolyte flow in vanadium flow batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.; Chen, D. Dynamic Model of a Vanadium Redox Flow Battery for System Performance Control. J. Sol. Energy Eng.-Trans. Asme 2014, 136, 021005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, H. Electrokinetic parameters of a vanadium redox flow battery with varying temperature and electrolyte flow rate. Renew. Energy 2019, 138, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krowne, C.M. Analytical current-voltage formulas in electrodes and concentration differences for VRFB. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 476, 143709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhang, B.W.; Bai, B.F.; Zhao, T.S. A transient electrochemical model incorporating the Donnan effect for all-vanadium redox flow batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 299, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loktionov, P.; Pichugov, R.; Konev, D.; Antipov, A. Reduction of VO2+ in electrolysis cell combined with chemical regeneration of oxidized VO2+ electrolyte for operando capacity recovery of vanadium redox flow battery. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 436, 141451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krowne, C.M. Spatial Distribution of Pressure Using Fluid Physics for the Vanadium Redox Flow Battery and Minimizing Fluid Crossover Between the Battery Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 020537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yasiri, M.A.A. Numerical and Experimental Study of New Designs of All-Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries for Performance Improvement. Doctoral Dissertation, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Li, M.-J.; Wang, R.-L.; Du, S.; Hung, T.-C. Design and optimization of guide flow channel for vanadium redox flow battery based on the multi-field synergy. J. Power Sources 2025, 650, 237526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.-W.; Chang, F.-Z.; Wei, H.-J.; Singh, B.; Arpornwichanop, A.; Jienkulsawad, P.; Chou, Y.-S.; Chen, Y.-S. Locating Shunt Currents in a Multistack System of All-Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 4648–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, M.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Grigoriev, S.; Hasanien, H.M.; Tang, X.; Li, R.; Sun, C. Polarization loss decomposition-based online health state estimation for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, J.; Shen, J.; Guo, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Fan, X.; et al. Operando quantitatively analyses of polarizations in all-vanadium flow batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 105, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, T.S. Determination of the mass-transport properties of vanadium ions through the porous electrodes of vanadium redox flow batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 10841–10848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.M.; Fathy, M.A. Novel paper-based potentiometric combined sensors using coumarin derivatives modified with vanadium pentoxide nanoparticles for the selective determination of trace levels of lead ions. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Jiang, H.R.; Zhang, B.W.; Chao, C.Y.H.; Zhao, T.S. Towards uniform distributions of reactants via the aligned electrode design for vanadium redox flow batteries. Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Xing, F.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Ma, X. Factor analysis of the uniformity of the transfer current density in vanadium flow battery by an improved three-dimensional transient model. Energy 2020, 194, 116839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roznyatovskaya, N.; Herr, T.; Kuettinger, M.; Fuehl, M.; Noack, J.; Pinkwart, K.; Tuebke, J. Detection of capacity imbalance in vanadium electrolyte and its electrochemical regeneration for all-vanadium redox-flow batteries. J. Power Sources 2016, 302, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Ling, C.Y.; Birgersson, E.; Vynnycky, M.; Han, M. Verified reduction of dimensionality for an all-vanadium redox flow battery model. J. Power Sources 2015, 279, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Z.; Hanawa, K.; Ju, D.; Luo, W.; Lyu, R.; Ishikawa, K.; Sato, S. Effects of Carbon Fiber Compression Ratio and Electrolyte Flow Rate on the Electrochemical Performance of Vanadium Redox Batteries. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 6646256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Numerical Value | Units of Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion coefficient of V2+ | 2.4 × 10−10 | m2/s |

| Diffusion coefficient of V3+ | 2.4 × 10−10 | m2/s |

| Diffusion coefficient of VO2+ | 3.9 × 10−10 | m2/s |

| Diffusion coefficient of VO2+ | 3.9 × 10−10 | m2/s |

| Diffusion coefficient of H+ | 9.3 × 10−9 | m2/s |

| Diffusion coefficient of SO42− | 1.3 × 10−9 | m2/s |

| Diffusion coefficient of HSO4− | 1.1 × 10−9 | m2/s |

| Degree of dissociation of HSO4− | 0.25 | 1 |

| Dissociation rate parameter for HSO4− | 10,000 | mol/(m3 × s) |

| Membrane proton concentration | 1.99 | mol/L |

| Initial negative concentration of H+ | 4447.5 | mol/m3 |

| Initial positive concentration of H+ | 5097.5 | mol/m3 |

| Initial negative concentration of HSO4− | 2668.5 | mol/m3 |

| Initial positive concentration of HSO4− | 3058.5 | mol/m3 |

| Electrode porosity | 0.6 | 1 |

| Pump efficiency | 0.9 | 1 |

| Permeability | 1.0 × 10−10 | m2 |

| c_total (Total vanadium concentration in the positive and negative electrode electrolytes) | 1500 | mol/m3 |

| Initial concentration of V2+ | SOC × c_total | mol/m3 |

| Initial concentration of V3+ | (1 – SOC) × c_total | mol/m3 |

| Initial concentration of VO2+ | (1 − SOC) × c_total | mol/m3 |

| Initial concentration of VO2+ | SOC × c_total | mol/m3 |

| SOC (State of Charge) | 0~1 | 1 |

| Anode reaction rate constant | 1.7 × 10−7 | m/s |

| Cathode reaction rate constant | 6.8 × 10−7 | m/s |

| Electrode conductivity | 1000 | S/m |

| Electrode specific surface area | 2.0 × 105 | m2/m3 |

| Parameters | Numerical Value | Units of Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Channel width | 3 | mm |

| Channel depth | 3 | mm |

| Rib electrode section width | 3 | mm |

| Electrode thickness | 6 | mm |

| Ion exchange membrane thickness | 0.18 | mm |

| Electrode edge length | 100 | mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shen, T.; Xie, X.; Xu, C.; Wu, S. Numerical Analysis of the Relationship Between Vanadium Flow Rate, State of Charge, and Vanadium Ion Uniformity. Symmetry 2026, 18, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010024

Shen T, Xie X, Xu C, Wu S. Numerical Analysis of the Relationship Between Vanadium Flow Rate, State of Charge, and Vanadium Ion Uniformity. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Tianyu, Xiaoyin Xie, Chongyang Xu, and Sheng Wu. 2026. "Numerical Analysis of the Relationship Between Vanadium Flow Rate, State of Charge, and Vanadium Ion Uniformity" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010024

APA StyleShen, T., Xie, X., Xu, C., & Wu, S. (2026). Numerical Analysis of the Relationship Between Vanadium Flow Rate, State of Charge, and Vanadium Ion Uniformity. Symmetry, 18(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010024