Computational Methods and Simulation of UAVs’ Micro-Motion Echo Characteristics Using Distributed Radar Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

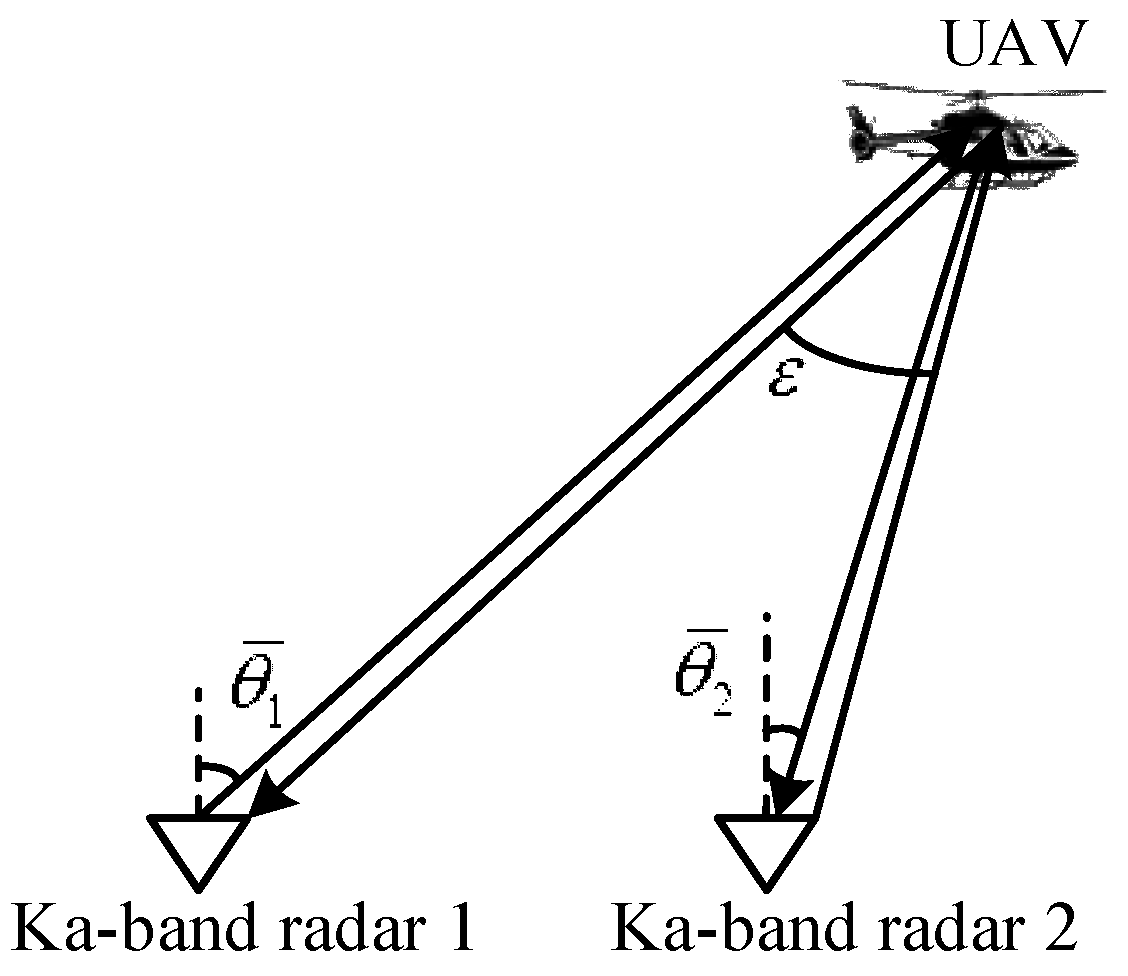

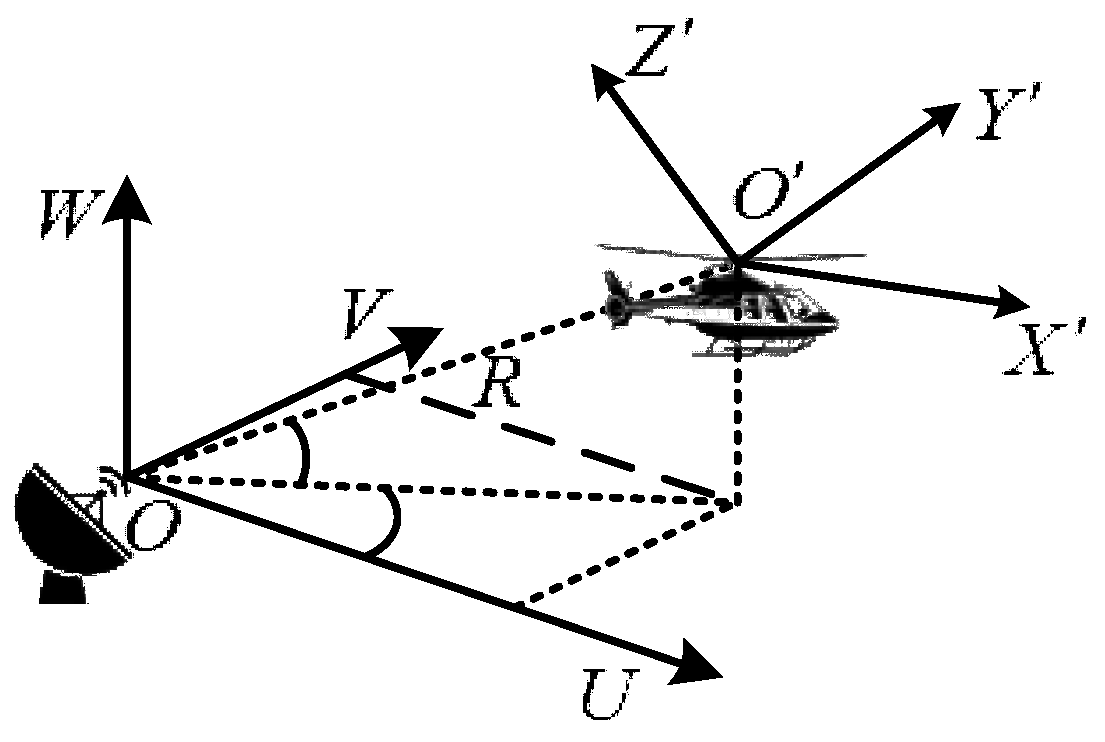

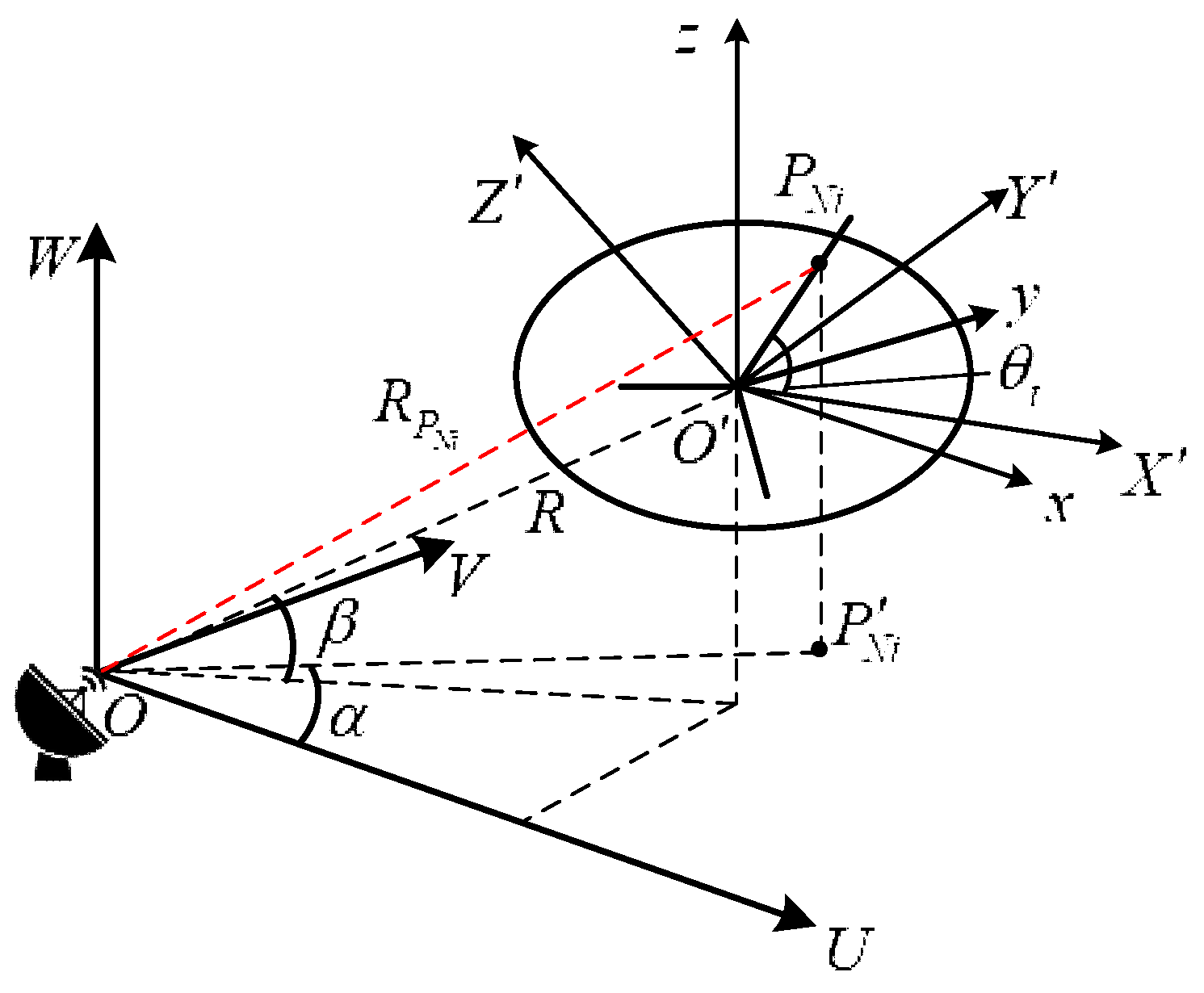

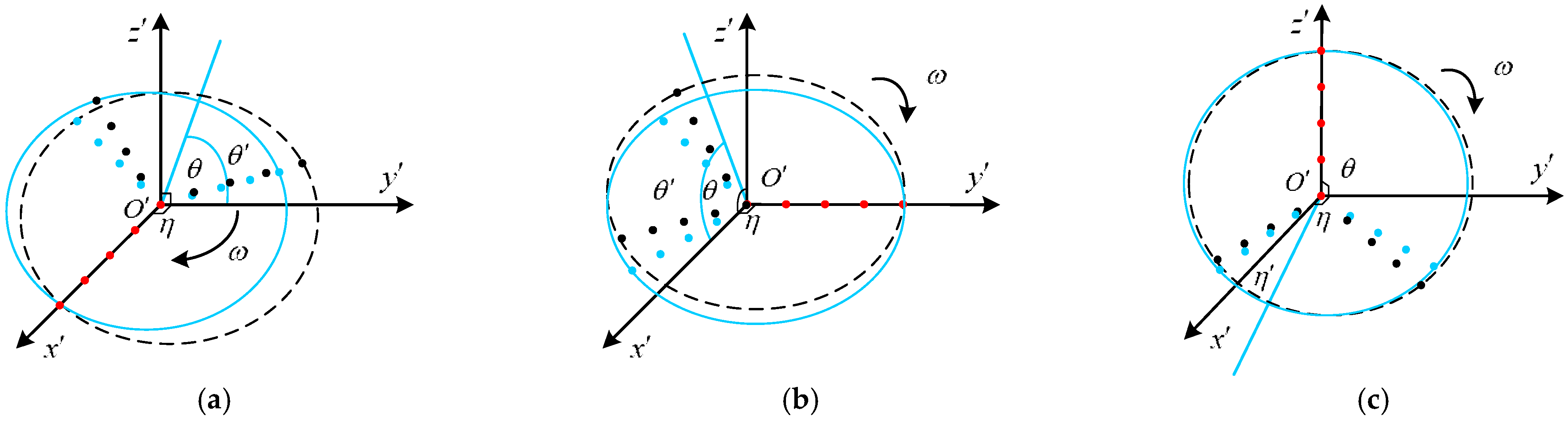

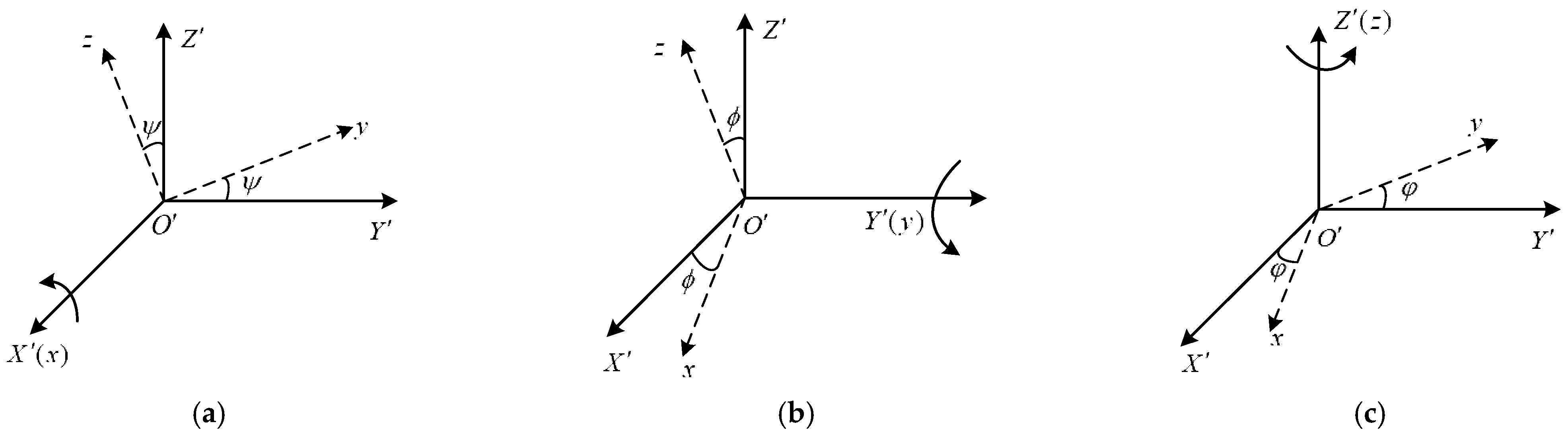

2. UAVs Echo Model Using Distributed Radar Detection

3. The Influence of UAVs’ Motion on Micro-Motion Characteristics Under Uncertain Conditions

3.1. Analysis of Micro-Motion Characteristics with Different UAV Motion Speeds

3.2. Analysis of the Micro-Motion Characteristics Under Different UAVs Attitude Angles

4. Simulation and Analysis

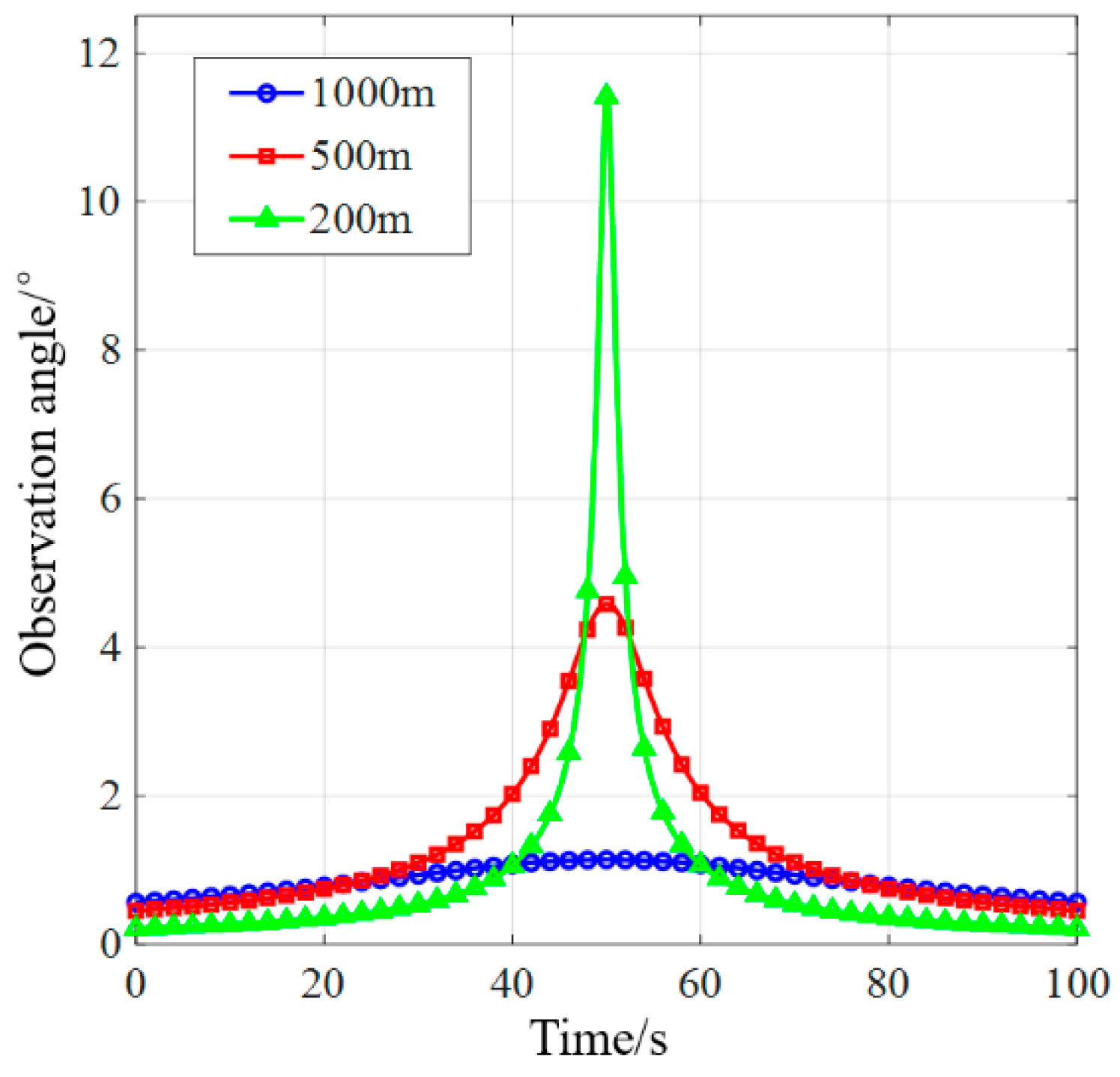

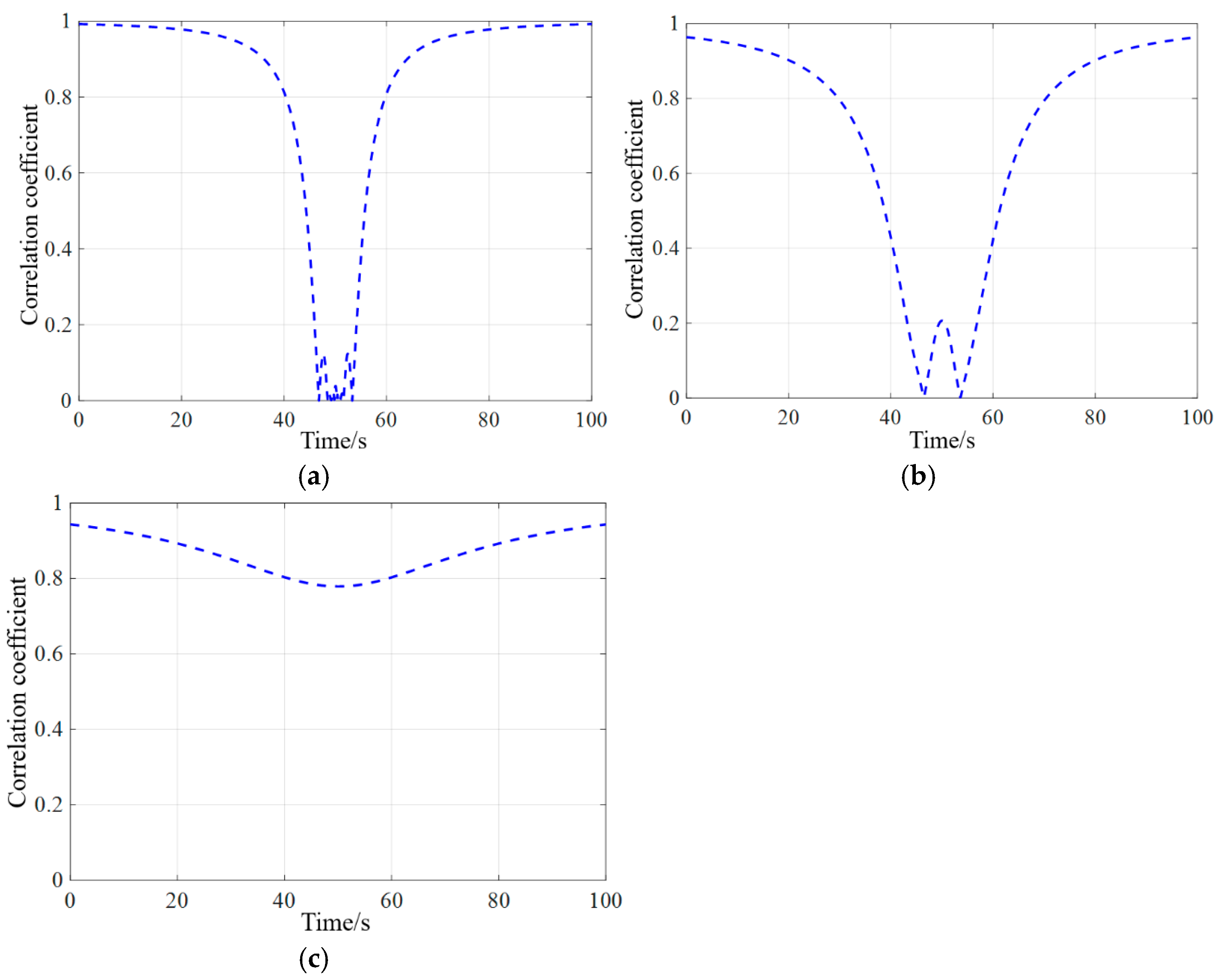

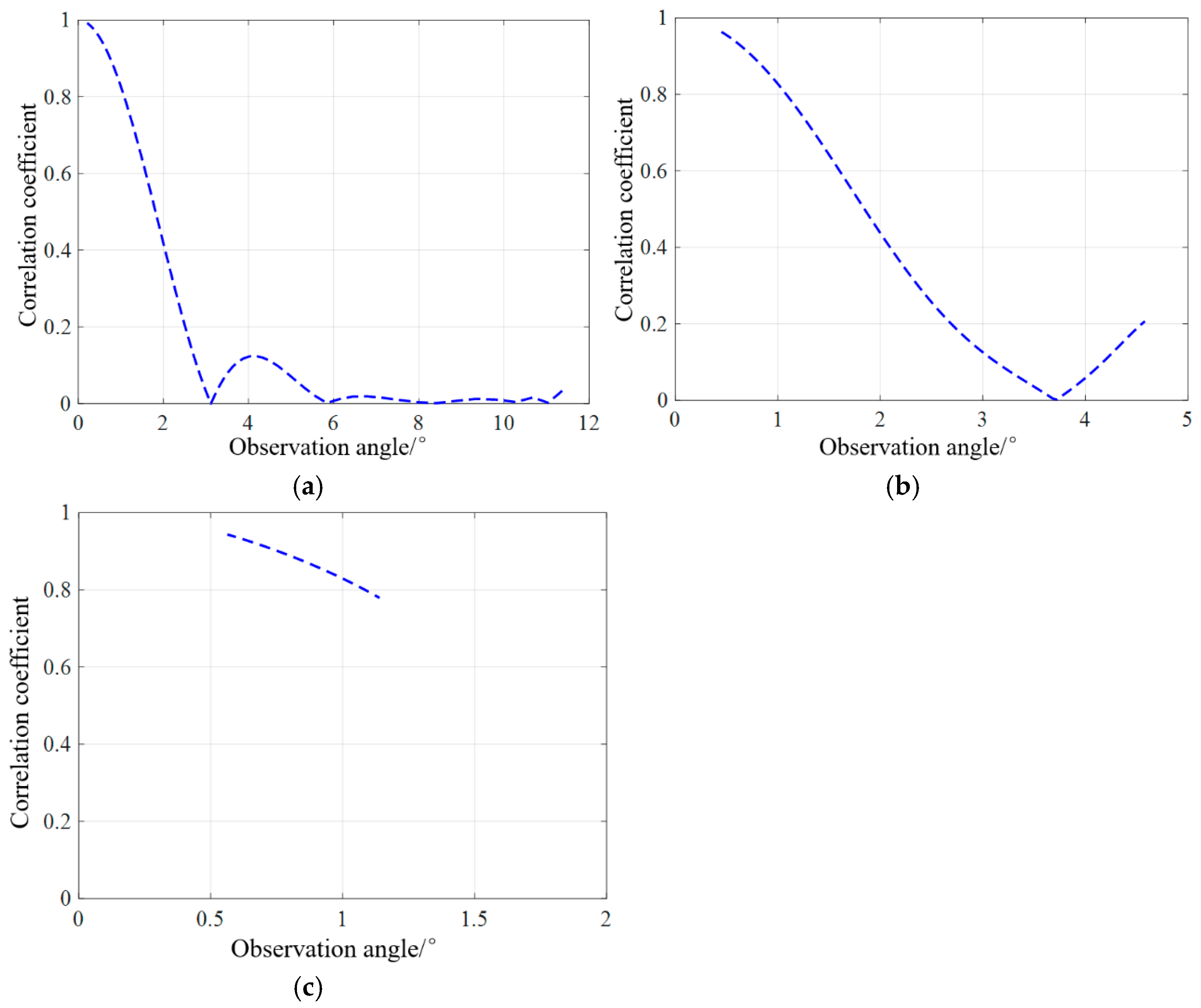

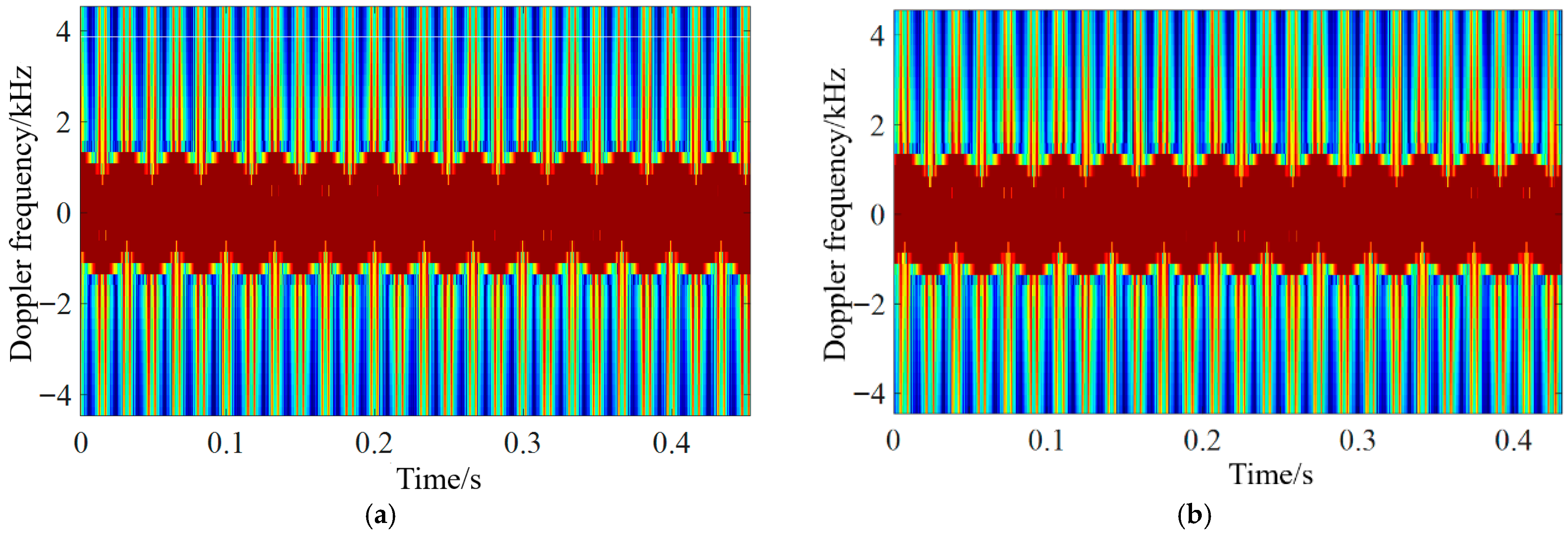

4.1. Spatial Correlation Analysis of UAV Echoes in Different Test Scenarios

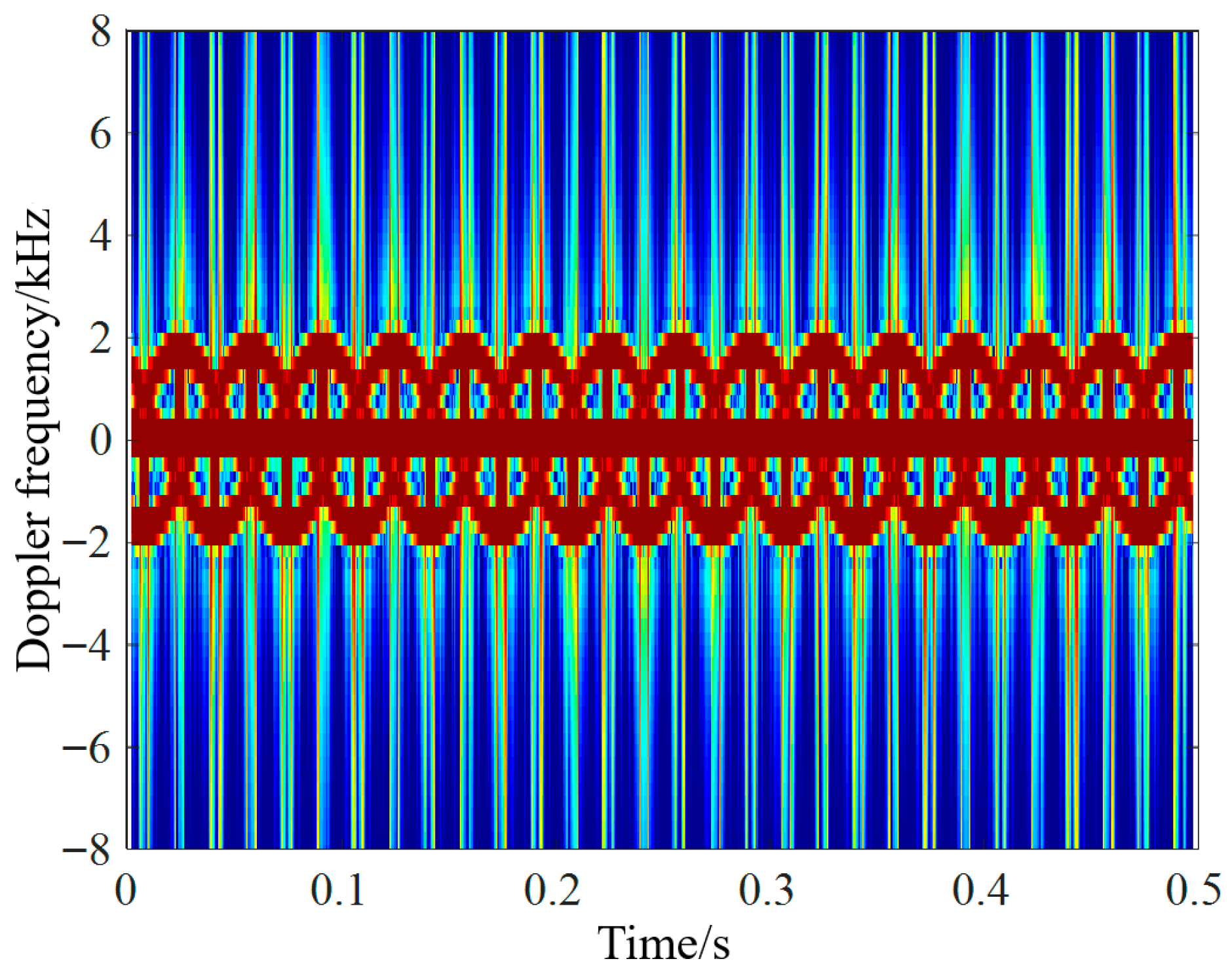

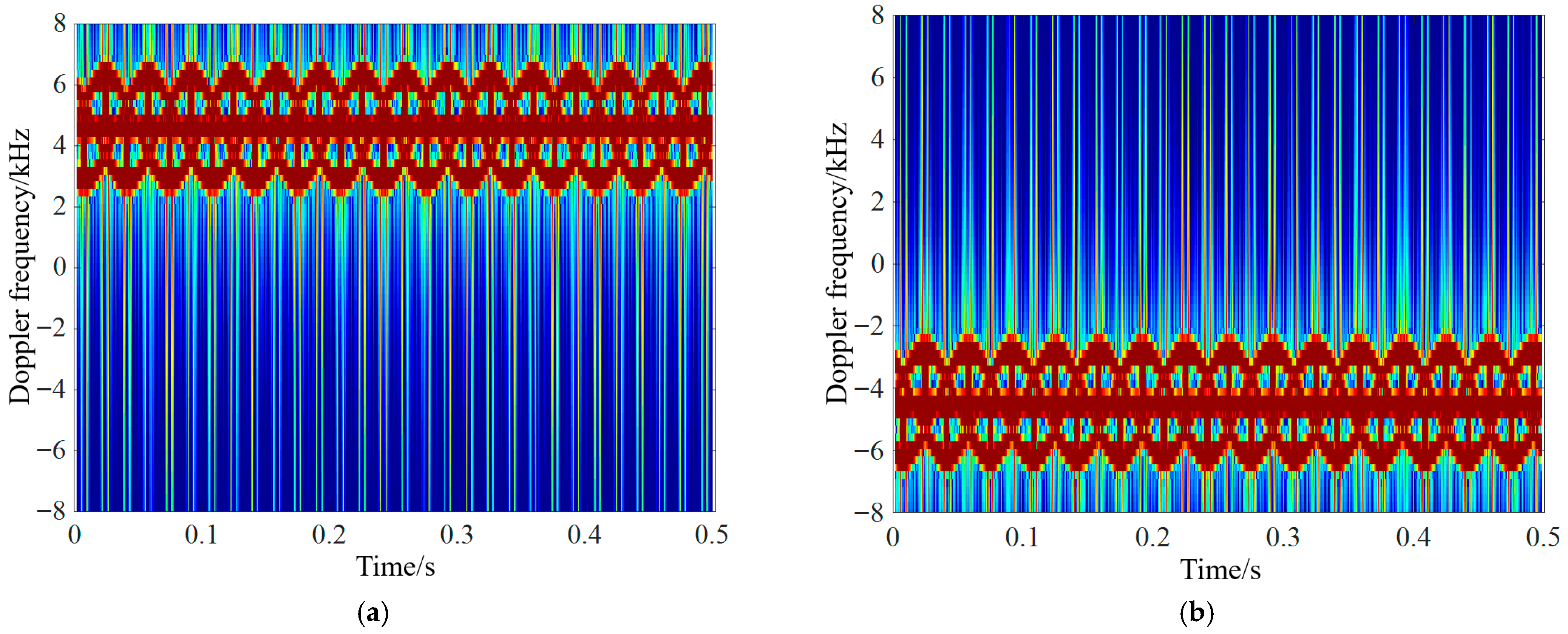

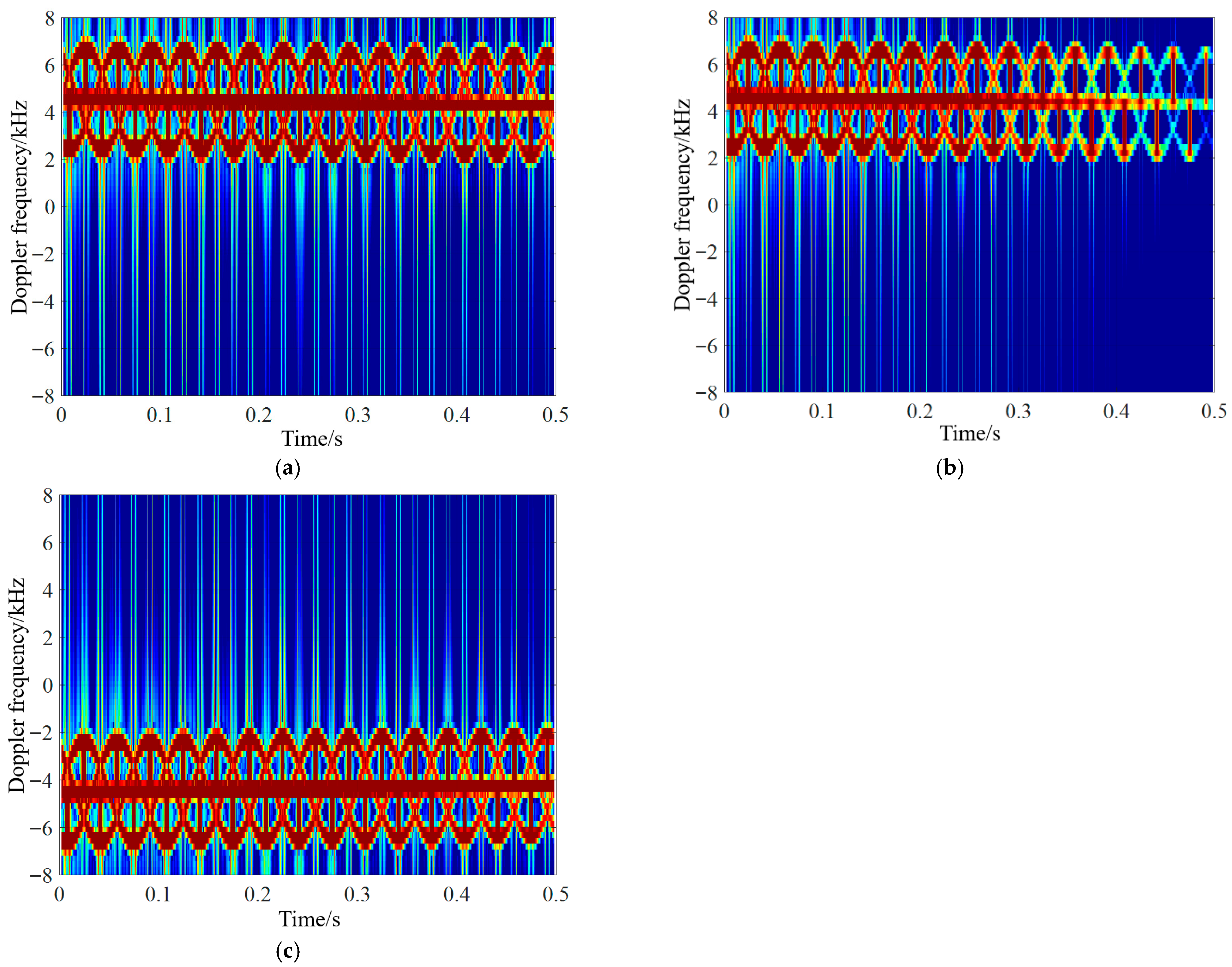

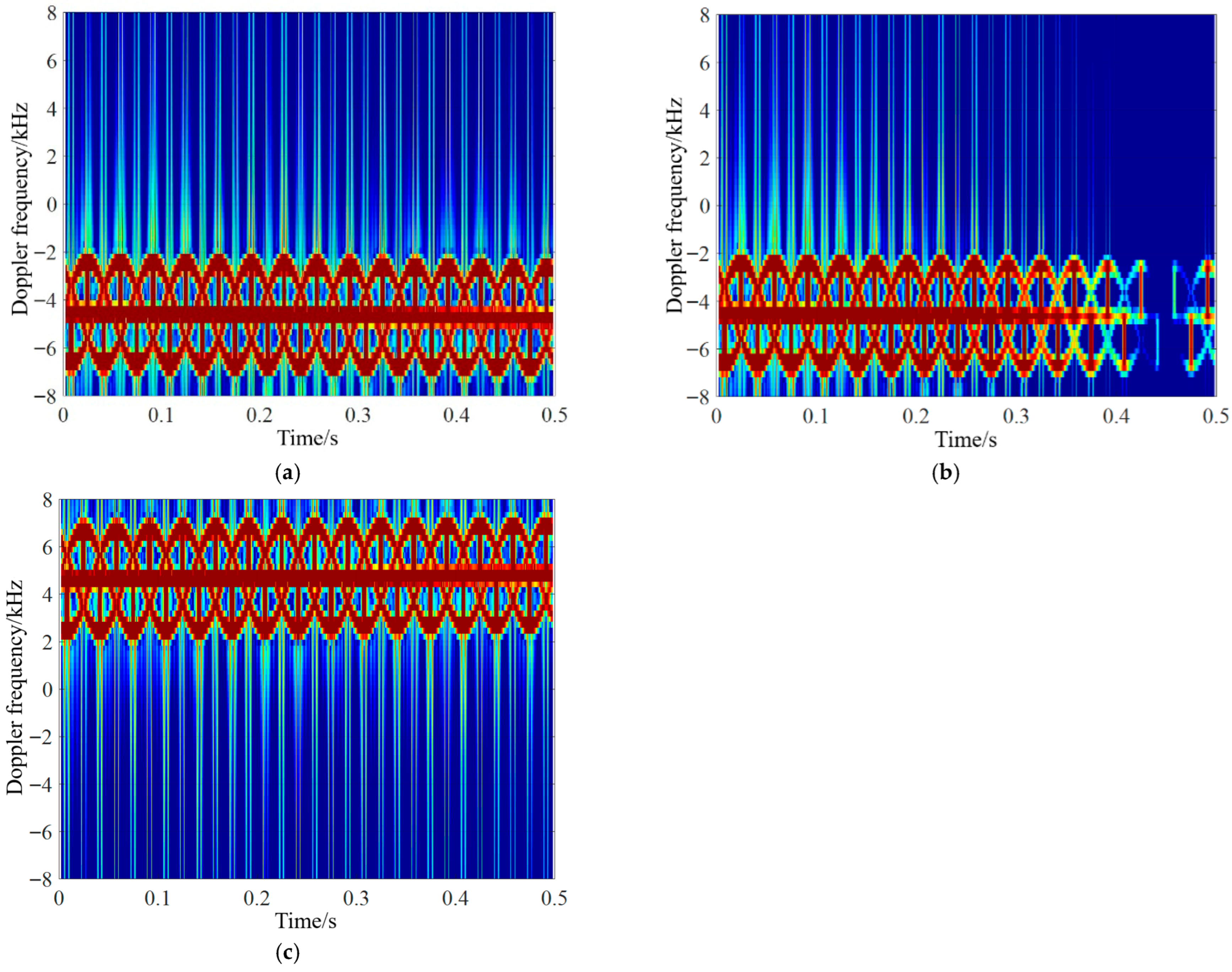

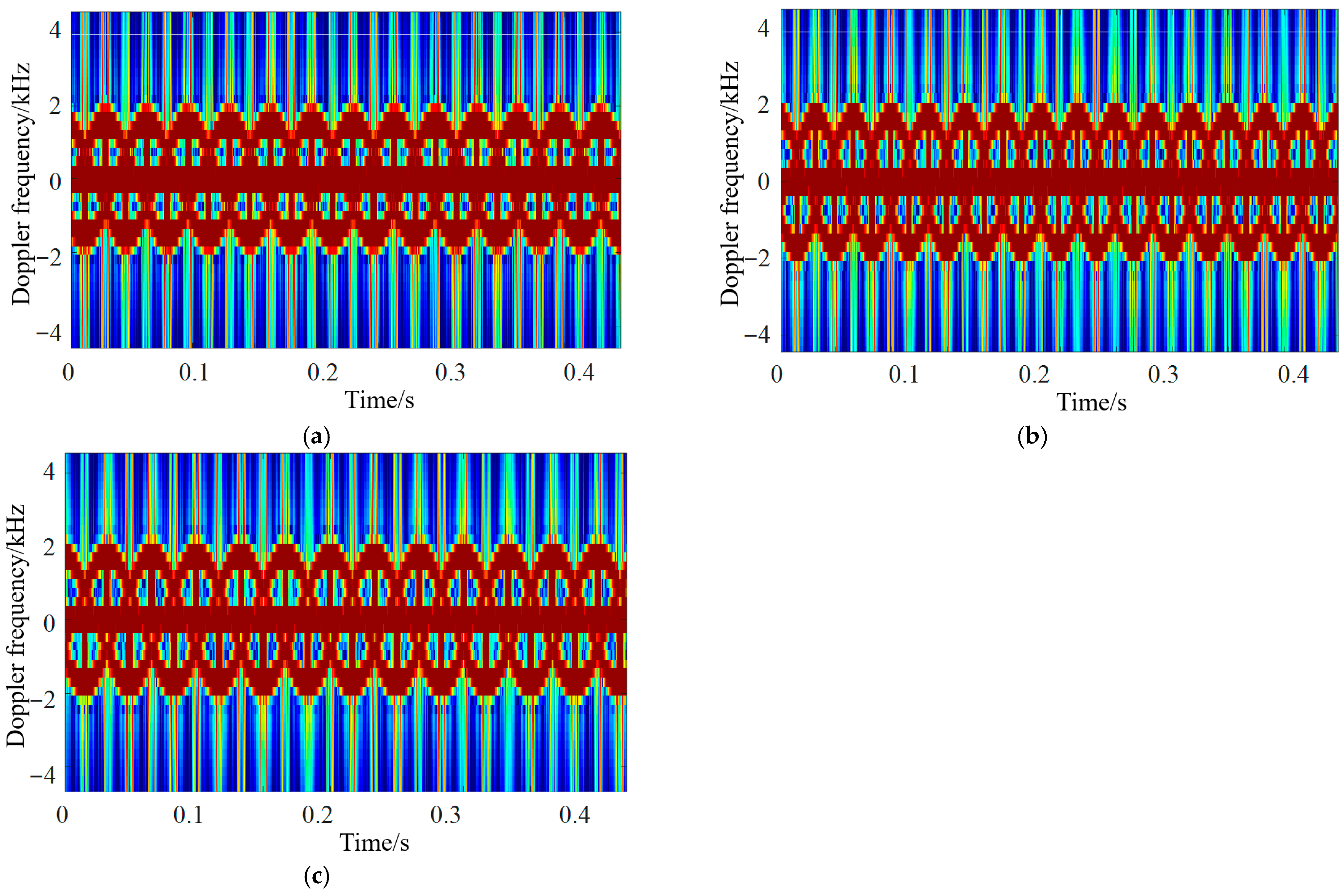

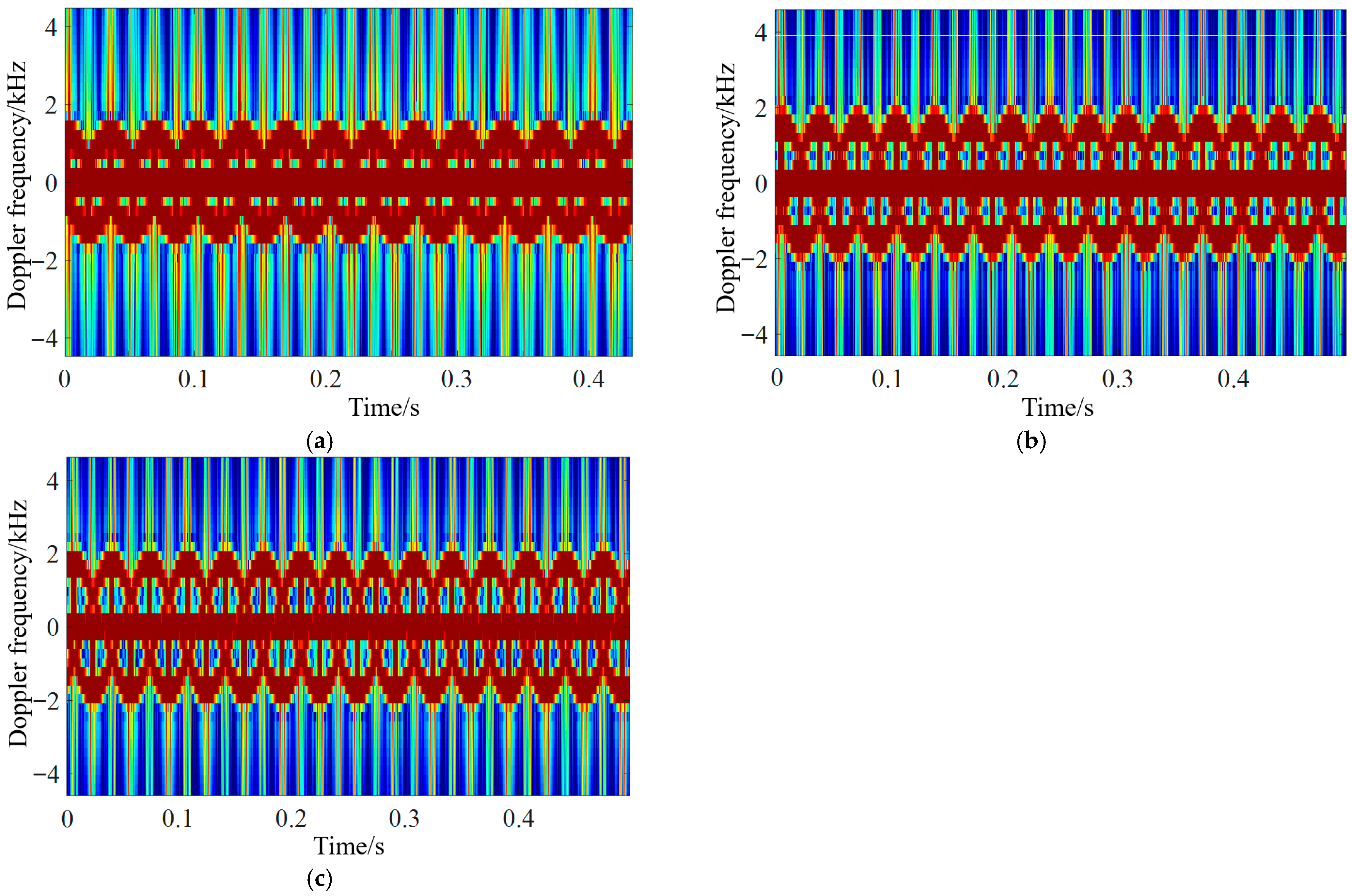

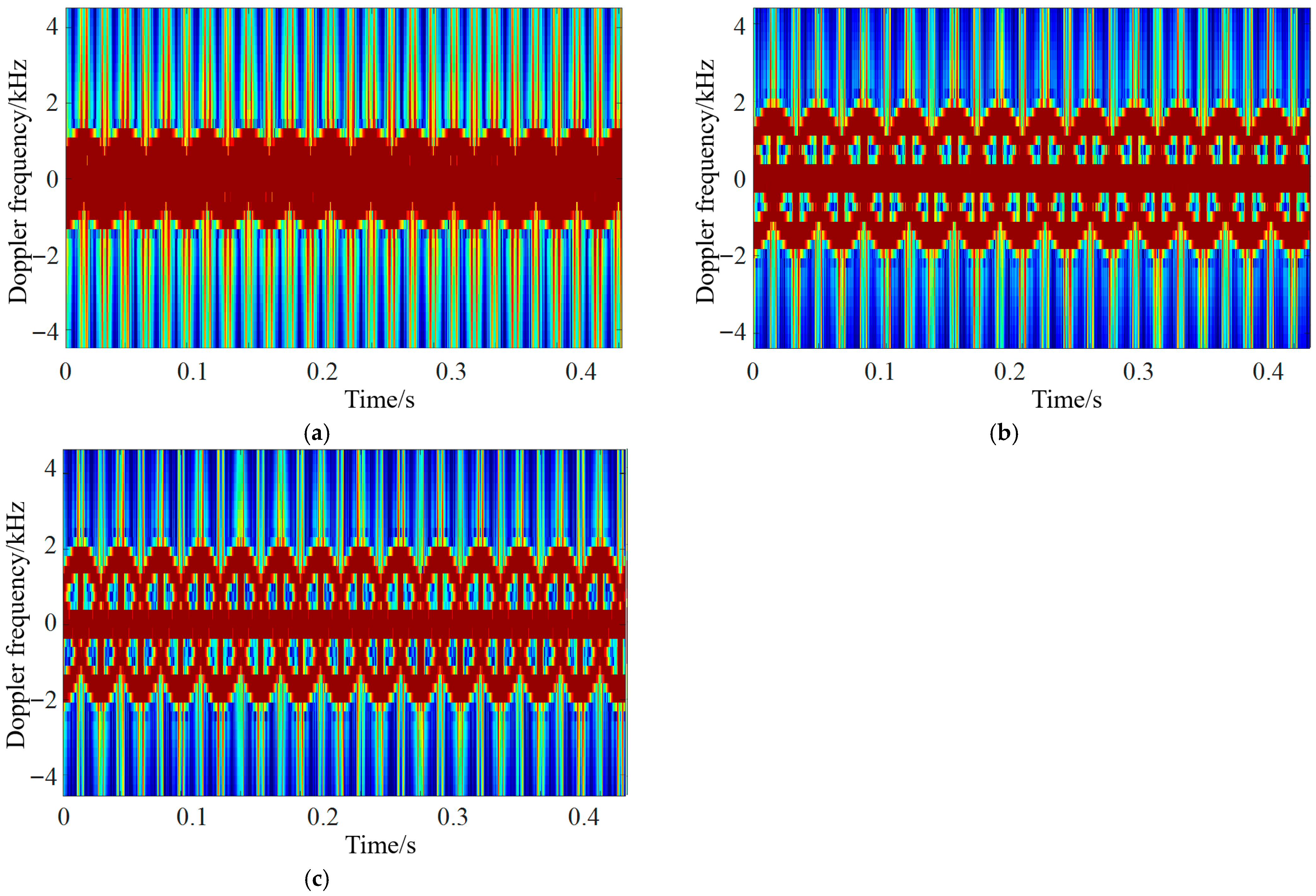

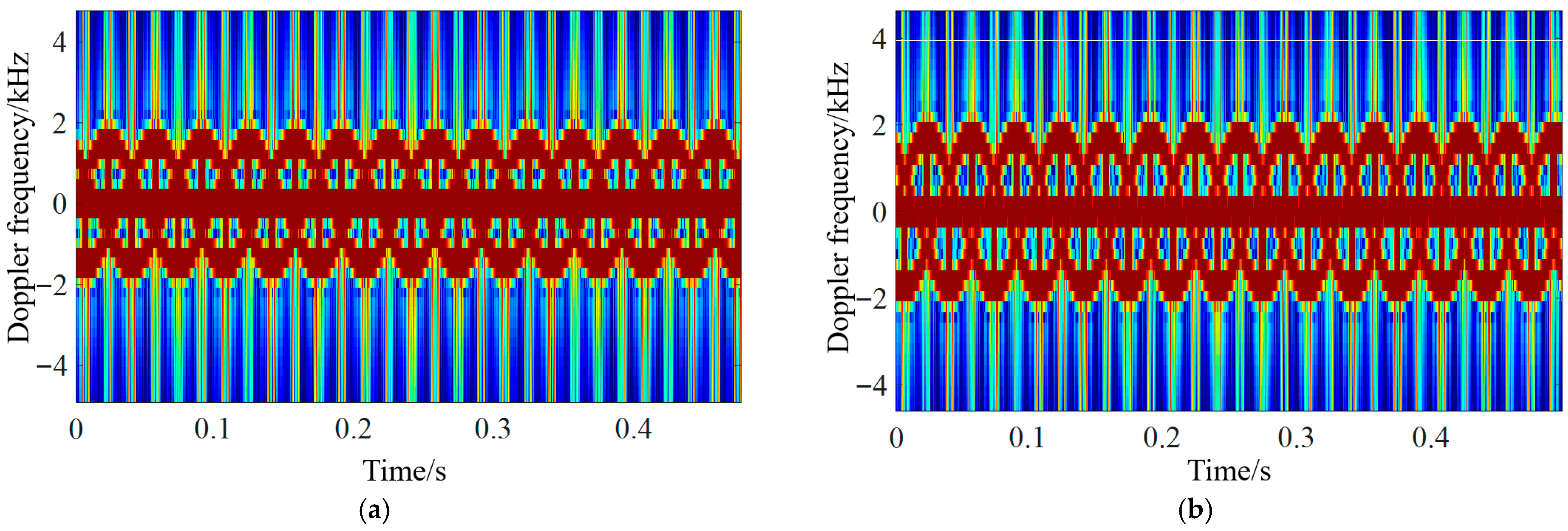

4.2. Analysis of UAV Micro-Motion Echo Characteristics in Different Motion States and at Attitude Angles

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, X. Research on Radar Key Technology for Small UAV Detection; University of Electronic Science and Technology of China: Chengdu, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, X.; Zhuang, D.; Xie, H. Detection methods for low-slow-small, U.A.V. Command. Control. Simul. 2020, 42, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Miao, C.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, W. Current status and future prospects of research on radar detection of “Low, Slow and Small” drones. Natl. Def. Technol. 2023, 44, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Xie, W. Advances on radar detection technology for rotorcraft unmanned aerial vehicles. Telecommun. Eng. 2024, 64, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Cao, J.; Yang, F.; Gao, J.; Zhang, L.; Cui, X.; Hao, Q. Advances in long-range low-slow-small target detection technology. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2024, 61, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Duttenhefner, J.L.; ElSaid, A.A.; Klug, P.E. Machine learning to detect, classify, and count blackbirds damaging agriculture using drone-based imagery: Supporting AI-driven automation for deployment of damage management tools. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 92, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Rao, B.; Luo, P. Detection performance analysis of low slow and small target based on LFMCW radar. J. Signal Process. 2019, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Passafiume, M.; Rojhani, N.; Collodi, G.; Cidronali, A. Modeling small UAV micro-doppler signature using millimeter-wave FMCW radar. Electronics 2021, 10, 747. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Hao, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z. Micro-Doppler analysis of moving helicopter’s rotor blades. Infrared Laser Eng. 2015, 44, 118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, W.; Wan, X.; Yi, J. Analytical expression of the time-frequency features of the near-field and far-field micro-motion echo based on local scattering centers. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2022, 44, 2867–2877. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, J. Multi-rotor UAV’s micro-Doppler characteristic analysis and feature extraction. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2019, 36, 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Cao, F. Rotor blades echo modeling and mechanism analysis of flashes phenomena. Acta Phys. Sin. 2016, 65, 281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Nan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Guan, J. Experimental research on radar micro-Doppler of flying bird rotor, U.A.V. Chin. J. Radio Sci. 2021, 36, 704–714. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Yang, J. Modeling of helicopter rotor blades’ echoes and its characteristic analysis. J. Air Force Early Warn. Acad. 2015, 29, 322–327. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Y.; Ding, C. An estimation method of micro-movement parameters of UAV based on the concentration of time-frequency. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2020, 42, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Xie, L.; Mo, Y. Radar echo characteristic analysis parameter estimation method for rotor U.A.V. J. Natl. Univ. Def. Technol. 2025, 47, 202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Li, G.; Huo, C.; Yin, H. Classification of drones based on micro-doppler radar signatures using dual radar sensors. J. Radars 2018, 7, 557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Tao, F.; Peng, G. Mixed loss-guided modular regression for dependent system reliability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 267, 111898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Dai, Y.; Song, Y.; Jin, T. Efficient near-field radar microwave imaging based on joint constraints of low-rank structured sparsity at low, S.N.R. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2025, 73, 2962–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zhou, J.; Chen, S.; Ding, H. Pseudo-Trapezoidal fast factorized backprojection algorithm for near-field sparse MIMO array 3-D imaging. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Xia, S.; Lv, M.; Chen, W.; Yang, J. Modeling of radar echoes of helicopter in motion state and analysis on its micro-motion characteristics. J. Air Space Early Warn. Res. 2024, 38, 79–84, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.B.; Choi, J.H.; Cho, B.L.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.T. Analysis of micro-doppler signatures of small UAVs based on doppler spectrum. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 3252–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Zhao, P.; Sun, T.; Li, K. Research on target signal acquisition model and simulation of distributed radar echoes. Comput. Simul. 2016, 33, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Wei, X.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, L.; Yang, J. Rotor targets radar echo modeling and its influence on micro-motion characteristics. J. China Acad. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2019, 14, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Q.; Ma, J. Photonic-assisted generation of fast switchable multi-format LFM waveforms with a tuned bandwidth for a joint radar-communication system. Opt. Commun. 2025, 574, 131097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Ma, D.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, L. Stealth Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Penetration Efficiency Optimization Based on Radar Detection Probability Model. Aerospace 2024, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Xu, W.; Liu, H.; Hao, J.; Min, Z.; Zhu, D. A high precision estimation algorithm for multi-channel wide-area surveillance ground moving target indication mode based on maximum likelihood method. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2024, 18, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K.; Tsagaanbayar, D.; Nakamura, R. ISAR imaging for drone detection based on backprojection algorithm using millimeter-wave fast chirp modulation MIMO radar. IEICE Commun. Express 2024, 13, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delleji, T.; Slimeni, F. RF-YOLO: A modified YOLO model for UAV detection and classification using RF spectrogram images. Telecommun. Syst. 2025, 88, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Niu, Y.; Yu, X.; Fan, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Zou, A.-M. Paying more attention on backgrounds: Background-centric attention for UAV detection. Neural Netw. 2025, 185, 107182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abro, G.E.M.; Abdallah, A.M. Graph Attention Networks for Anomalous Drone Detection: RSSI-Based Approach with Real-world Validation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 273, 126913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motion State | State 1 | State 2 | State 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceleration motion | The UAV is flying towards the station, Speed is 20 m/s, Acceleration is 3 m/s, Forward tilt speed is 5°/s. | The UAV is flying towards the station, Speed is 20 m/s, Acceleration is 3 m/s, Forward tilt speed is 10°/s. | The UAV is flying away from the station, Speed is −20 m/s, Acceleration is −3 m/s, Forward tilt speed is 5°/s. |

| Deceleration motion | The UAV is flying away from the station, Speed is −20 m/s, Acceleration is 3 m/s, Backward tilt speed is 5°/s. | The UAV is flying away from the station, Speed is −20 m/s, Acceleration is 3 m/s, Backward tilt speed is 10°/s. | The UAV is flying towards the station, Speed is 20 m/s, Acceleration is −3 m/s, Backward tilt speed is 5°/s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, T.; Song, X. Computational Methods and Simulation of UAVs’ Micro-Motion Echo Characteristics Using Distributed Radar Detection. Symmetry 2026, 18, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010026

Zhang T, Song X. Computational Methods and Simulation of UAVs’ Micro-Motion Echo Characteristics Using Distributed Radar Detection. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Tao, and Xiaoru Song. 2026. "Computational Methods and Simulation of UAVs’ Micro-Motion Echo Characteristics Using Distributed Radar Detection" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010026

APA StyleZhang, T., & Song, X. (2026). Computational Methods and Simulation of UAVs’ Micro-Motion Echo Characteristics Using Distributed Radar Detection. Symmetry, 18(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010026