1. Introduction

The classical theory of thermoelasticity, while providing a fundamental framework for analyzing thermomechanical interactions, suffers from the inherent limitation of predicting infinite thermal wave speeds, a physical paradox that becomes particularly significant under high-frequency loading conditions and extreme thermal environments. The seminal work of Lord and Shulman [

1] first resolved this issue through the introduction of a single relaxation time in the constitutive equations, establishing a generalized dynamical theory that ensures finite thermal wave propagation speeds through a hyperbolic heat equation. The theoretical foundations and practical applications of these advanced thermoelasticity theories have been comprehensively documented in seminal works, such as Hetnarski and Eslami’s [

2], which systematically present the advanced theory of thermal stresses. Concurrently, sophisticated analytical methodologies have been developed to handle the resulting complex coupled equations, with techniques like the eigenfunction expansion method demonstrated by Das and Bhakata [

3] providing powerful tools for solving simultaneous field equations in mechanics. Green and Naghdi [

4] proposed a groundbreaking thermoelastic framework that eliminates energy dissipation, offering a distinct thermodynamic perspective on thermal–mechanical interactions. Building upon these foundational theories, contemporary research has focused on developing increasingly refined heat conduction models. The application domain of generalized thermoelasticity has been substantially expanded to encompass various physical phenomena and complex material behaviors. Othman et al. [

5] examined the crucial influence of temperature-dependent material properties under gravity fields across different thermoelasticity theories. The framework has also been extended to advanced materials and complex loading conditions, as demonstrated by Abbas and Zenkour [

6]. They applied Green–Naghdi’s theory to analyze magnetic field effects on thermal shock in a fiber-reinforced anisotropic half-space. Furthermore, Sarkar and Atwa [

7] addressed fracture mechanics applications by solving two-temperature problems. The study analyzes Mode-I crack problems within a fiber-reinforced thermoelastic solid, based on the principles of Green–Naghdi theory. Saeed [

8] developed a new generalized model for heat conduction that incorporates the effects of porosity on a poro-thermoelastic medium, considering cases both with and without energy dissipation. Panja and Mandal [

9] investigated a finite linear Mode-I crack model within a thermoelastic transversely isotropic medium based on Green–Naghdi theory. Most recently, Abo-Dahab et al. [

10] have further expanded this field by investigating Rayleigh wave propagation in a transversely isotropic visco-thermoelastic medium, evaluating the combined effects of rotation and the Hall current. The analysis incorporates models both with and without energy dissipation, in addition to viscous and microstructural effects. Despite these significant advancements, a research gap persists in the holistic integration of multi-phase-lag heat conduction, two-temperature theory, viscoelastic behavior, and the combined influences of external fields with temperature-dependent material properties in anisotropic media under complex boundary conditions. Therefore, this study aims to develop a comprehensive model that unifies these sophisticated aspects into a coherent framework, providing enhanced predictive capabilities for the thermomechanical behavior of advanced engineering materials in extreme environments. The pursuit of enhanced accuracy in modeling heat conduction mechanisms has been a central focus in the evolution of generalized thermoelasticity. While earlier models introduced single- and dual-phase-lags, a significant paradigm shift occurred with the advent of the three-phase-lag (3PHL) model which offers a more nuanced description of thermal energy transport by accounting for the time delays separating the heat flux, the temperature gradient, and the thermal displacement gradient. The foundational work of Choudhuri [

11] formally established this thermoelastic three-phase-lag model (3PHL), providing a new framework for analyzing microstructural interactions in the heat transfer process. Subsequent research has been dedicated to exploring the implications and applications of this advanced constitutive model. In this model, the Fourier law of heat conduction is modified by employing Taylor series expansions, introducing two distinct phase lags, one for the heat flux vector and another for the thermal displacement gradient, while retaining terms up to appropriately higher orders. The resulting high-order three-phase-lag heat conduction model with energy dissipation encompasses earlier thermoelasticity models as specific cases. When the elapsed times during a transient process are very small, say about 10

7 s, or the heat flux is very high, the 3PHL model has great importance in exploring various applications related to nuclear boiling, electron–phonon interactions, scattering, pure phonon scattering, etc. Kumar and Chawla [

12] conducted a comparative analysis of plane wave propagation in anisotropic media which demonstrated critical differences in the predictions of the three-phase-lag and two-phase-lag models, underscoring the importance of model selection. The mathematical rigor and applicability of the 3PHL framework were further extended by Marin et al. [

13], who constructed a generalized model to describe the behavior of three-phase-lag dipolar thermoelastic solids, incorporating additional microstructural degrees of freedom. Recent years have witnessed refined applications and integrations of the 3PHL theory. Singh et al. [

14] analyzed the thermoelastic interaction within a semi-infinite elastic solid influenced by a heat source, employing the three-phase-lag model incorporating a memory-dependent derivative. Zenkour [

15] employed an advanced three-phase-lag model within the Green–Naghdi framework to investigate thermal diffusion in an unbounded solid with a spherical cavity, demonstrating the model’s efficacy in handling complex geometries. The modeling of multi-physical field interactions in complex materials represents a frontier of research in modern continuum mechanics and generalized thermoelasticity. Recent investigations have progressively integrated the coupled effects of electromagnetic fields, material microstructure, thermal processes, and mechanical pre-stresses to enable accurate prediction of material performance in extreme environments.

The evolution of generalized thermoelasticity has consistently aimed to overcome the limitations of classical theory, particularly its prediction of infinite thermal wave speeds and its inability to capture complex material behaviors under extreme conditions. As research has progressed, there has been a marked shift toward developing models that incorporate more realistic physical properties and coupled phenomena. A significant advancement in this direction was demonstrated by Youssef [

16], who took the problem of a generalized thermoelastic response in an infinite medium with a spherical cavity and investigated it using a state-space approach. The analysis specifically accounts for variable thermal conductivity and ramp-type heating. Recent years have witnessed the emergence of even more sophisticated theoretical frameworks. Wang et al. [

17] investigated generalized thermoelasticity, considering variable thermal material properties. Their findings revealed that these variable properties have a substantial influence on thermoelastic behaviors, especially on the intensity of the thermoelastic response. Xiong et al. [

18] conducted a study on the fiber-reinforced generalized thermoelasticity problem under thermal stress, taking into account the influence of temperature-dependent variable thermal conductivity. Megahid et al. [

19] explored the Moore–Gibson–Thompson thermoelasticity model, which was applied to simulate the thermoelectric behavior of a conductive semi-solid surface under variable thermal shock, extending the analysis to encompass non-Fourier heat conduction with higher-order derivatives. Concurrently, the interplay between opto-thermo-mechanical fields has garnered significant attention. According to Ailawalia et al. [

20], Green–Naghdi theory is advanced for thermo-microstretch solids through the integration of variable thermal conductivity, addressing the nuanced thermal–mechanical behavior of materials with inner structure. State-of-the-art studies are advancing these frameworks by accounting for nonlocal and memory-dependent phenomena. He [

21] explored the issue of fractional thermoelasticity in a diffusive half-space, considering variations in thermal conductivity and diffusivity.

A magnetic field interacts with a thermoelastic medium by linking its thermal and elastic characteristics, generating an electromagnetic force that impacts both deformation and heat transfer. This phenomenon, referred to as magneto-thermoelasticity, alters stress, strain, and temperature distributions within the material. It holds significant relevance in disciplines such as geophysics and nuclear engineering. The extent of these effects is influenced by the intensity of the applied magnetic field and the intrinsic properties of the material. Das and Kanoria [

22] addressed the magneto-thermo-elastic interaction caused by thermal shock on a stress-free boundary of a half-space composed of a perfectly conducting medium. It was analyzed within the framework of two-temperature generalized thermoelasticity, taking energy dissipation into account. The significance of rotational effects and initial stress conditions had been previously highlighted in the earlier work of Said [

23], which examined deformation in a generalized magneto-thermoelastic medium characterized by a two-temperature model, internal heat generation, rotation, and hydrostatic initial stress, demonstrating the profound influence of these factors on thermoelastic response. Hussien and Bayones [

24] explored Rayleigh surface waves in fiber-reinforced solid anisotropic magneto-thermo-viscoelastic materials. Their work specifically focused on a pre-stressed elastic layer of finite thickness positioned over a homogeneous, pre-stressed elastic half-space, both of which were subjected to rotational effects. Yadav [

25] explored the behavior of plane wave propagation within an initially stressed, rotating magneto-thermoelastic solid half-space, using the framework of fractional-order derivative thermoelasticity. Lata and Himanshi [

26] investigated the impact of the fractional order parameter on a two-dimensional orthotropic magneto-thermoelastic solid within the framework of generalized thermoelasticity. The study focused on a scenario without energy dissipation, incorporating fractional order heat transfer while also considering the influence of the Hall current. Kaur and Singh [

27] explored the issue of Rayleigh wave propagation in a transversely isotropic magneto-thermoelastic diffusive medium incorporating memory-dependent derivatives. This research examines an isotropic, symmetrical thermoelastic medium, a material class defined by its uniform properties in all directions. Such materials find significant applications across multiple disciplines, including general engineering design, geophysics for modeling subsurface layers, and acoustics for wave propagation studies. A particularly relevant application is within aerospace engineering, where analyzing thermoelastic response under extreme conditions is crucial for structural integrity and thermal management.

This study presents a comprehensive framework grounded in the refined three-phase-lag Green–Naghdi theory to analyze the behavior of a thermoelastic solid exhibiting variable thermal conductivity under magnetic field effects. A distinctive feature of the model is its integration of temperature-dependent thermal transport with fully coupled electromagnetic–thermomechanical interactions. Through this integrated approach, the research provides novel insights into wave propagation characteristics and thermal stress distribution in advanced materials. The results offer significant contributions for the design and optimization of functional materials operating under extreme thermomagnetic conditions.

5. Computational Analysis and Discussion

To illustrate the theoretical model, we now present numerical simulations that analyze the effects of a magnetic field, a reference temperature, and variable thermal conductivity. These results, based on the refined three-phase-lag Green–Naghdi type III theory, demonstrate their collective impact on the thermoelastic solid.

We calculate the numerical magnitudes of displacement, stresses, and temperature versus the distance, , at A comparison of the displacement components, ; the thermal temperature, and the stress components, ; versus the distance, , has been made in these cases:

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate the differences in the displacement components,

the temperature distribution,

and stress field components,

; for various magnitudes of the magnetic field

The behavior was investigated via the refined three-phase lag Green–Naghdi type III (3PHL G-N III) framework.

Figure 1 depicts the spatial fluctuation of vertical displacement,

, in a thermoelastic medium influenced by varying the intensity of a magnetic field. For all values of the magnetic field

all curves show a significant downward displacement near the surface, with a smooth decline toward zero as the distance,

, increases. It is clear that the values of

where

predict slightly higher displacement values compared to the values of

where

indicating that the strength of the magnetic field reduces the magnitude of

The influence of the magnetic field can be observed to dampen the system’s motion, effectively restricting the movement of the medium.

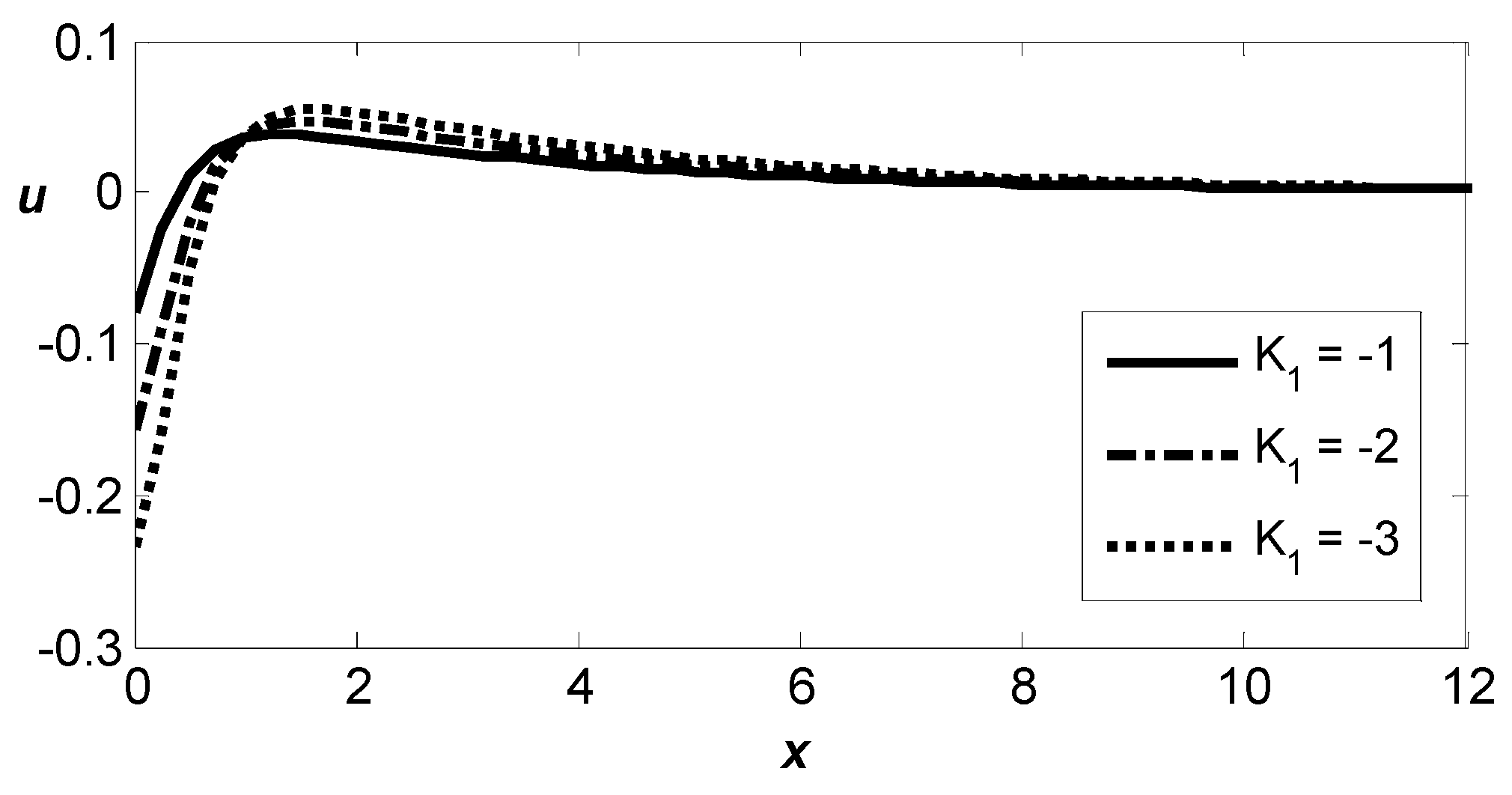

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial variation in horizontal displacement,

, in a thermoelastic medium influenced by varying the intensity of a magnetic field. For all values of the magnetic field

the curves display a notable upward shift, followed by a pronounced downward shift, eventually tapering off smoothly toward zero as the distance increases. It is clear that the magnetic field increases the magnitude of

and then decreases the magnitude of

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of thermal temperature influenced by the varying intensity of a magnetic field. All the curves display a notable upward shift, followed by a pronounced downward shift, eventually tapering off smoothly toward converging to zero with increasing distance. It is obvious that the magnitudes of

where

predict slightly higher magnitudes compared to the values of

where

indicating that the strength of the magnetic field leads to a reduction in the magnitude of

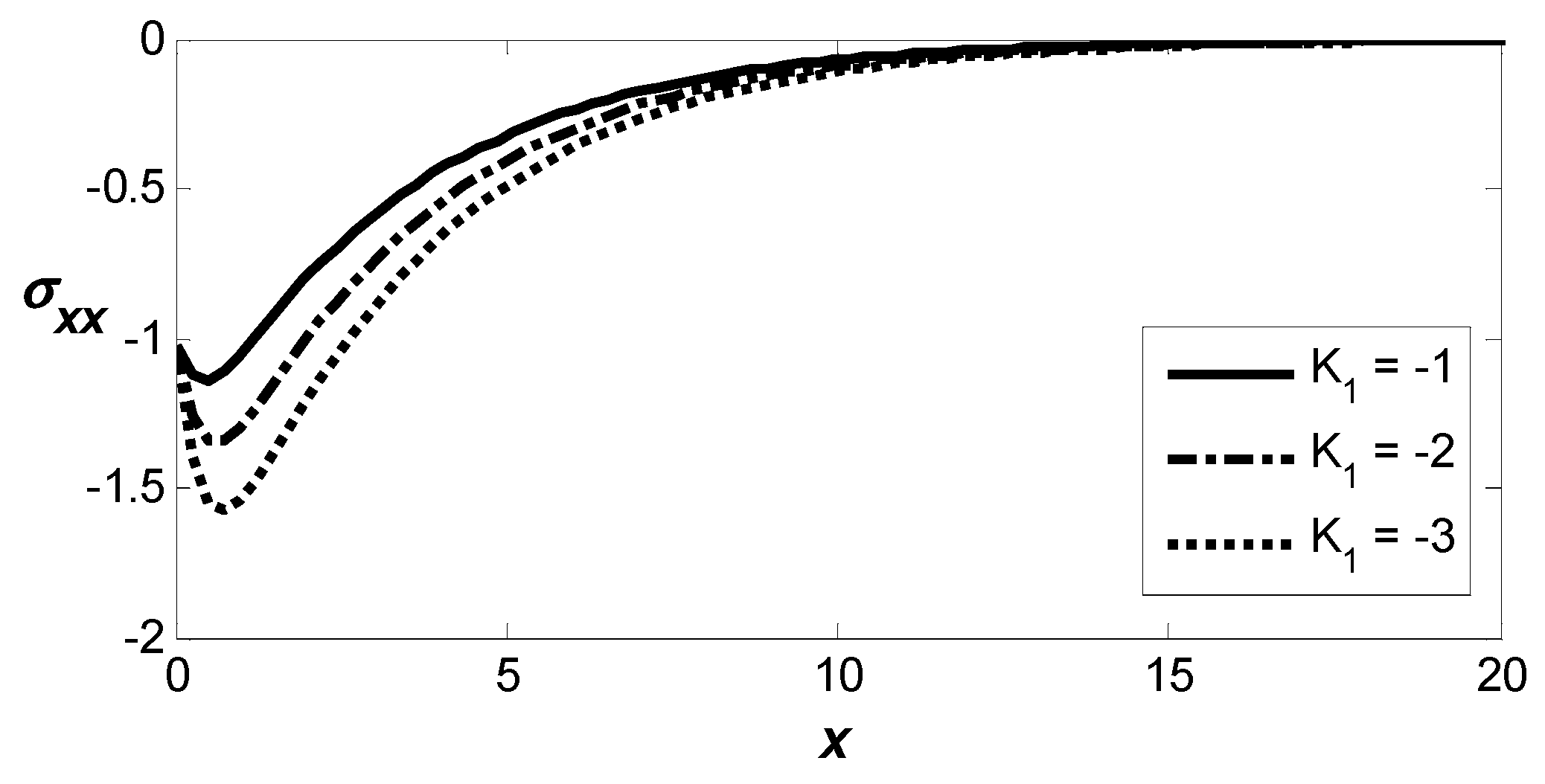

Figure 4 depicts the spatial variation in the normal stress component,

, which varies with the varying intensity of the magnetic field, starting at negative levels and conforming to the boundary conditions. All the curves depict an increase in the interval

followed by a gradual recovery toward zero as

increases. It is obvious that the magnitudes of

where

predict slightly higher magnitudes compared to the values of

where

indicating that higher magnetic field intensities elevate the values of

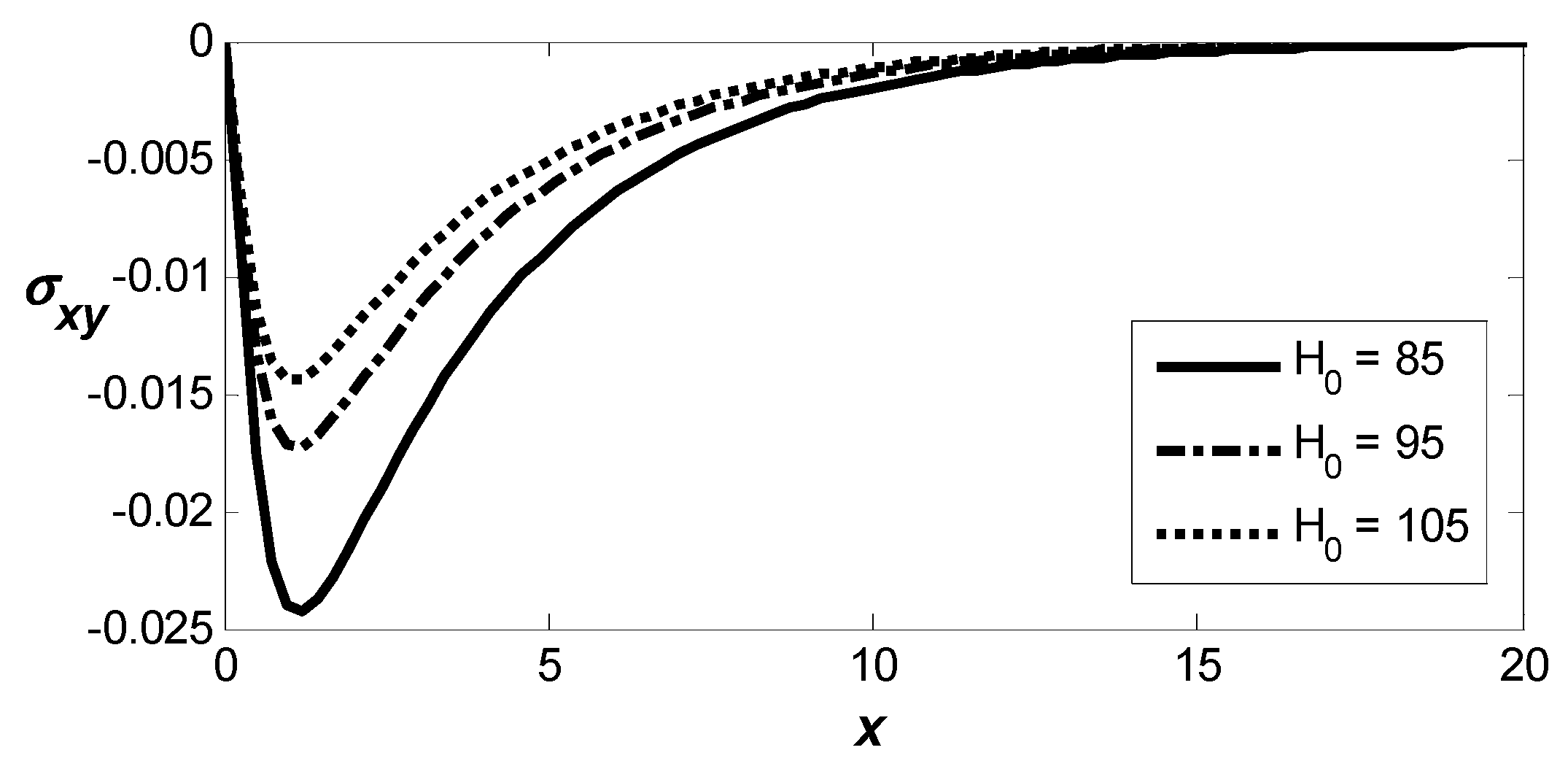

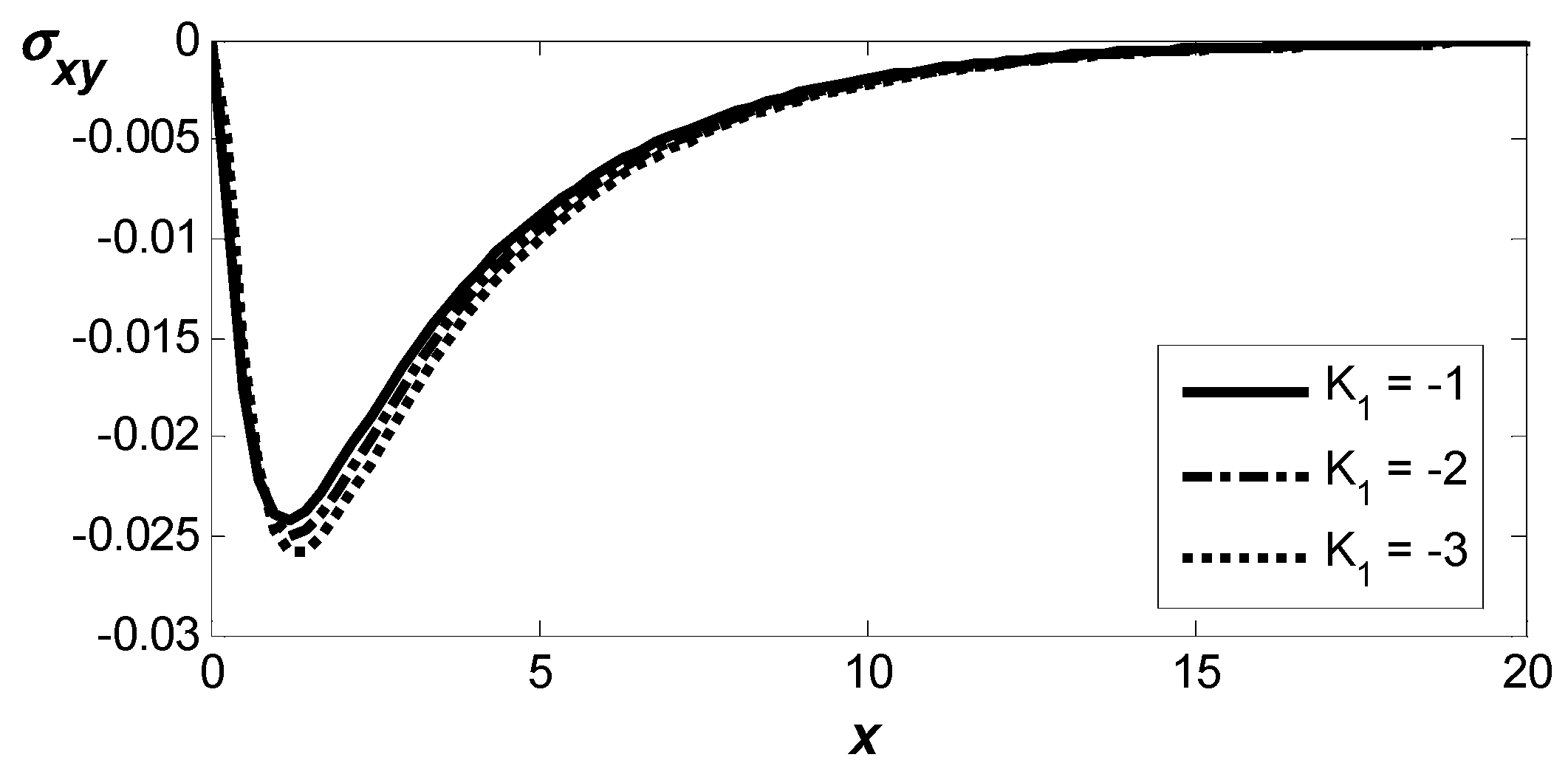

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of the shear stress component,

, spatially, thereby illustrating the magnetic field’s influence on the distribution. The solution starts at zero, thereby satisfying the boundary condition at that point. The magnitude of

drops sharply to a minimum, then recovers abruptly, and then gradually relaxes toward zero. An increase in magnetic field strength is shown to lead to higher corresponding values of

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the variations between the displacement components,

and the components of the stress field,

, for various magnitudes of the variable thermal conductivity

The behavior was investigated via the refined three-phase lag Green–Naghdi type III (3PHL G-N III) framework.

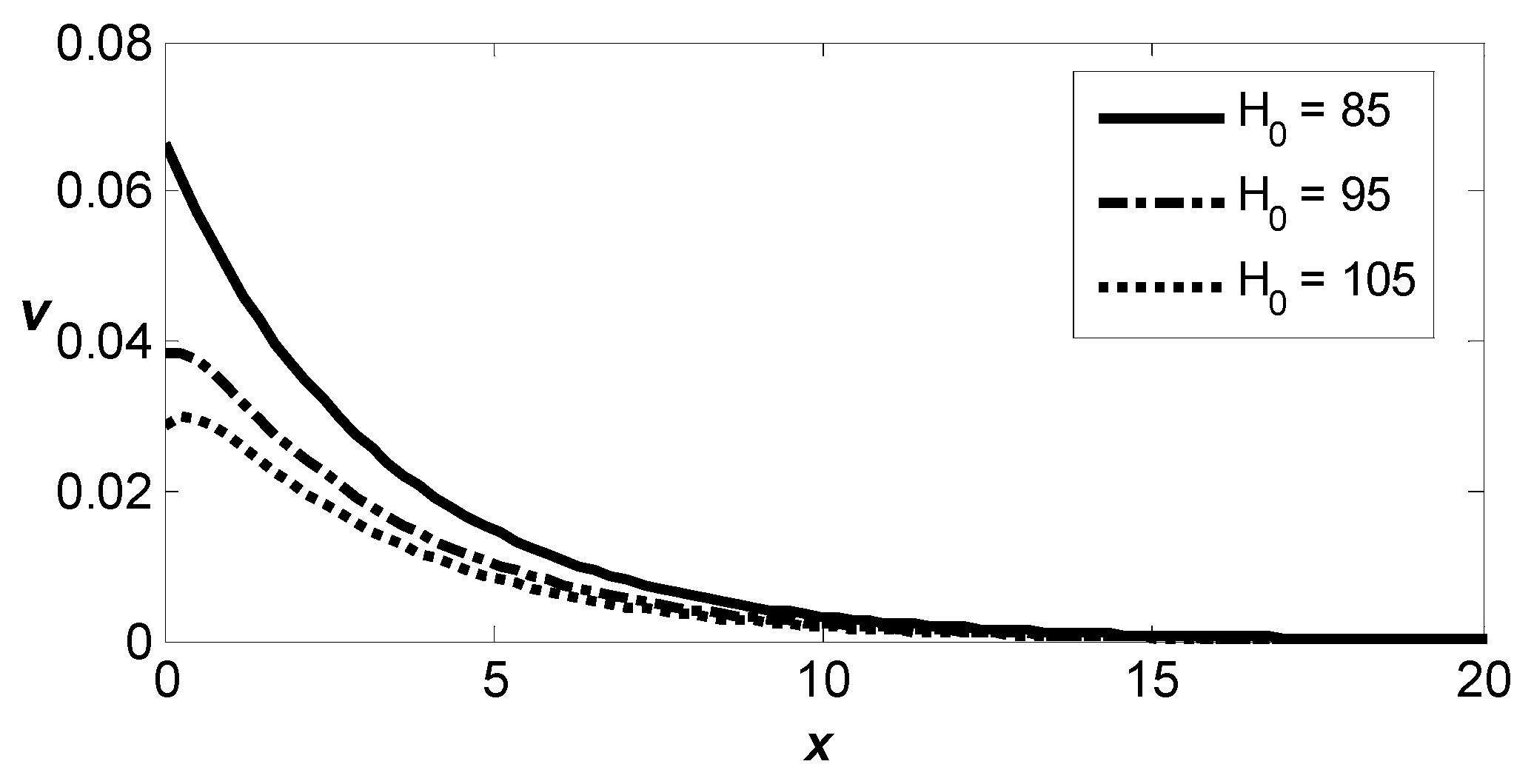

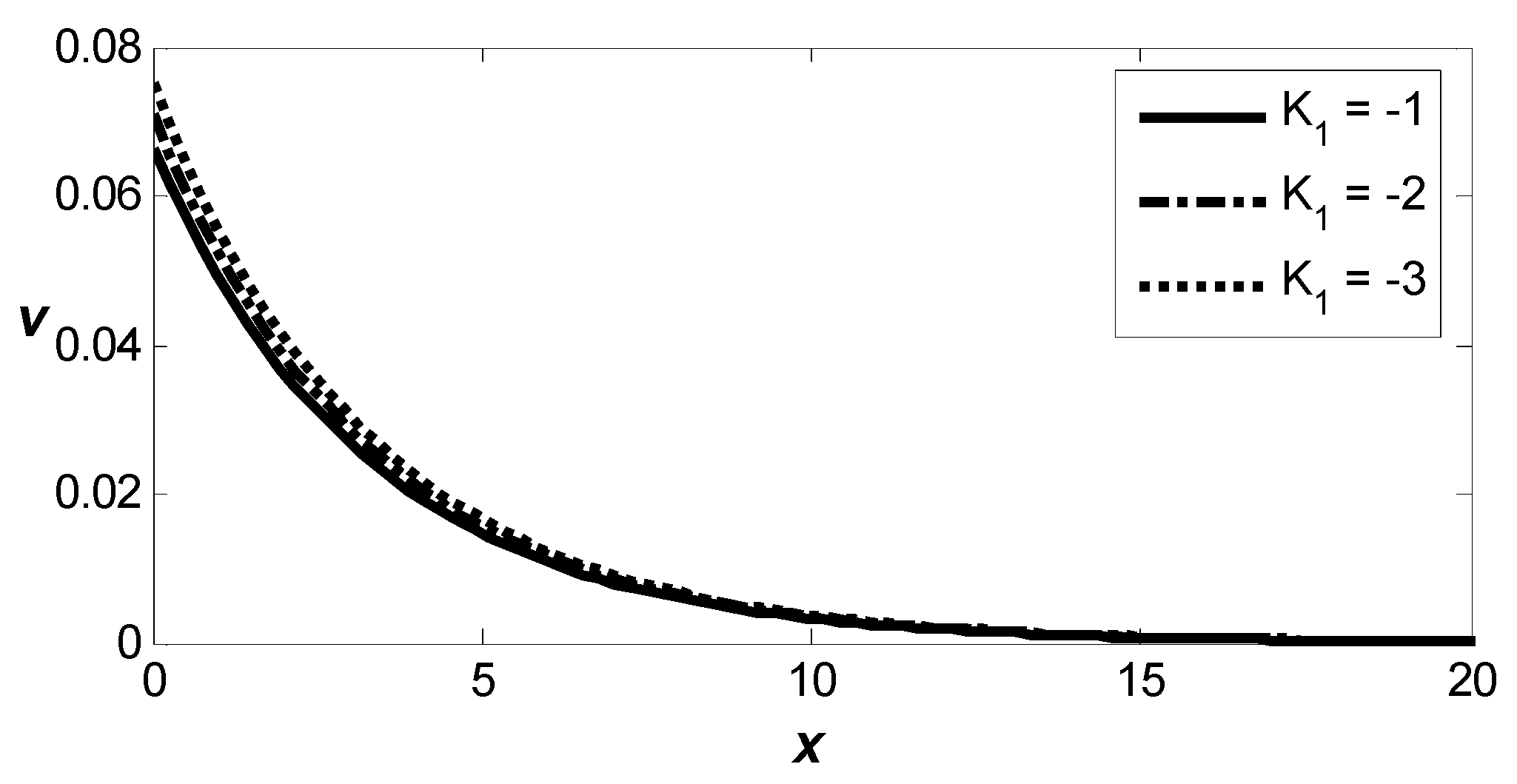

Figure 6 shows how the vertical displacement,

, varies spatially in a thermoelastic medium influenced by varying thermal conductivity. For all values of the variable thermal conductivity

all curves show a significant downward displacement near the surface, with a smooth decline toward zero as the distance,

, increases. It is clear that the magnitudes of

where

predict slightly lower displacement values compared to the magnitudes of

where

indicating that the variable thermal conductivity decreases the values of

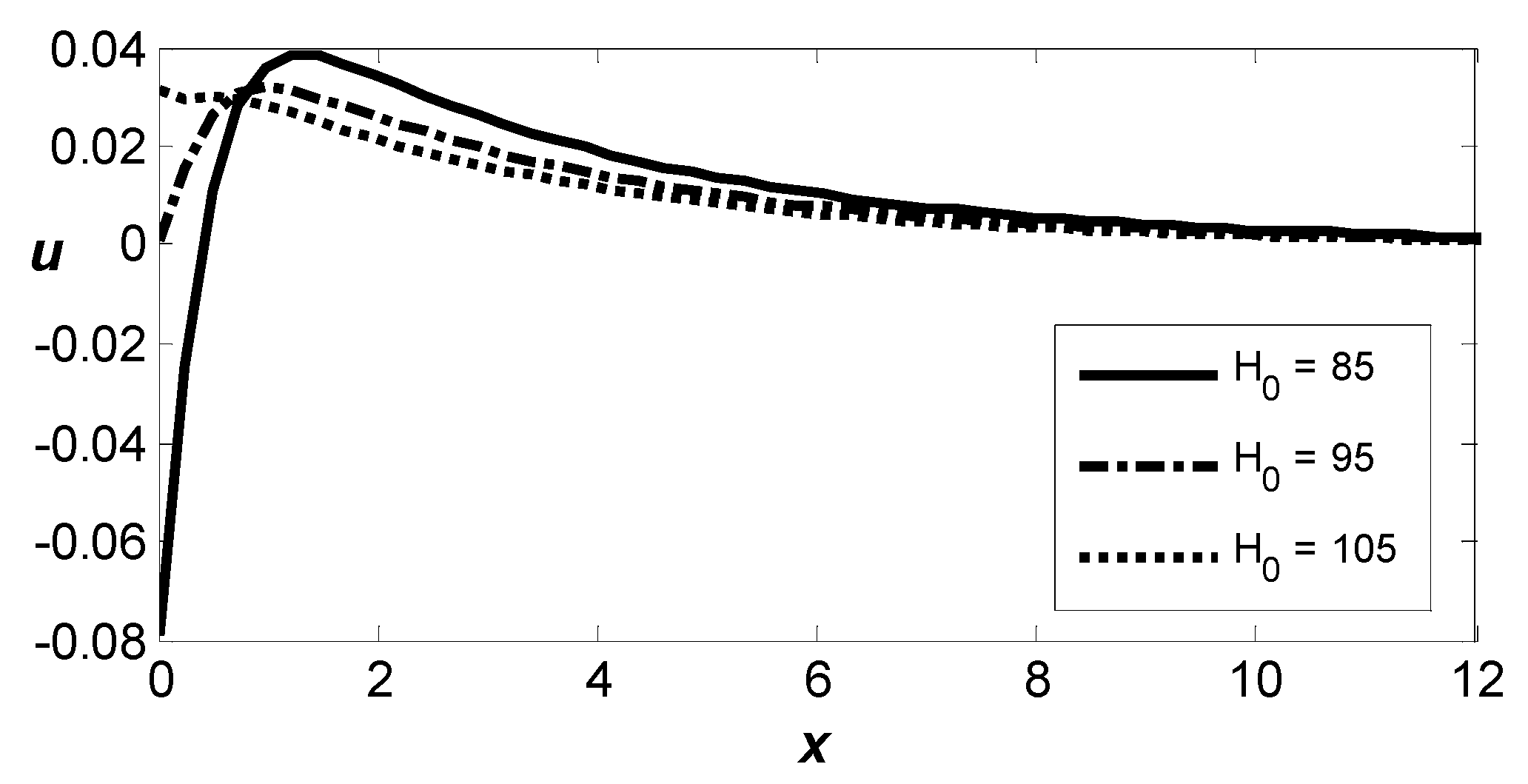

Figure 7 depicts the spatial distribution of the horizontal displacement component.

in a thermoelastic medium influenced by varying variable thermal conductivity. For all values of the variable thermal conductivity

the curves display a notable upward shift, followed by a pronounced downward shift, eventually tapering off smoothly toward zero as the distance increases. It is clear that the variable thermal conductivity increases then decrease magnitudes of

indicating that the varying variable thermal conductivity impacts the behavior of

Figure 8 shows how the spatial distribution of normal stress,

, varies with varying thermal conductivity. All the curves depict a notable downward shift, followed by a pronounced upward shift, eventually tapering off smoothly, asymptotically approaching zero with increasing distance. The analysis reveals that the magnitudes of

where

predict slightly higher values compared to the magnitudes of

where

indicating that the variable thermal conductivity results in an increase in

Figure 9 shows the distribution of the shear stress,

, plotted against spatial position, thereby illustrating the effect of variable thermal conductivity. The distribution of shear stress was plotted spatially.

decreases sharply to a distinct minimum before increasing abruptly and then gradually relaxing towards zero. It can be observed that an increase in the variable thermal conductivity leads to higher corresponding values of

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show the analysis of the variations between the displacement components,

; thermal temperature,

; and stress components,

; for various magnitudes of the reference temperature

The behavior was investigated via the refined three-phase lag Green–Naghdi type III (3PHL G-N III) framework.

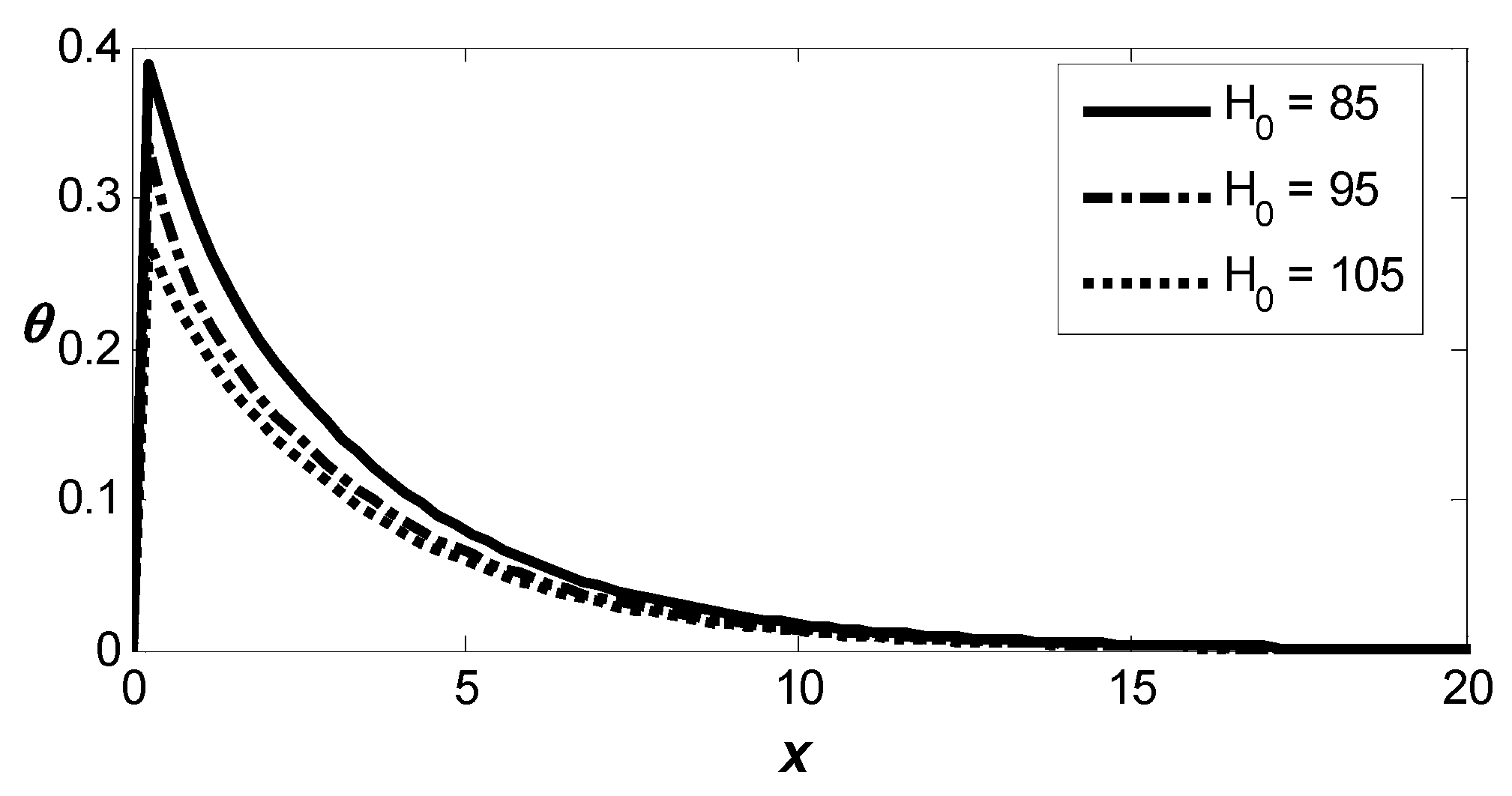

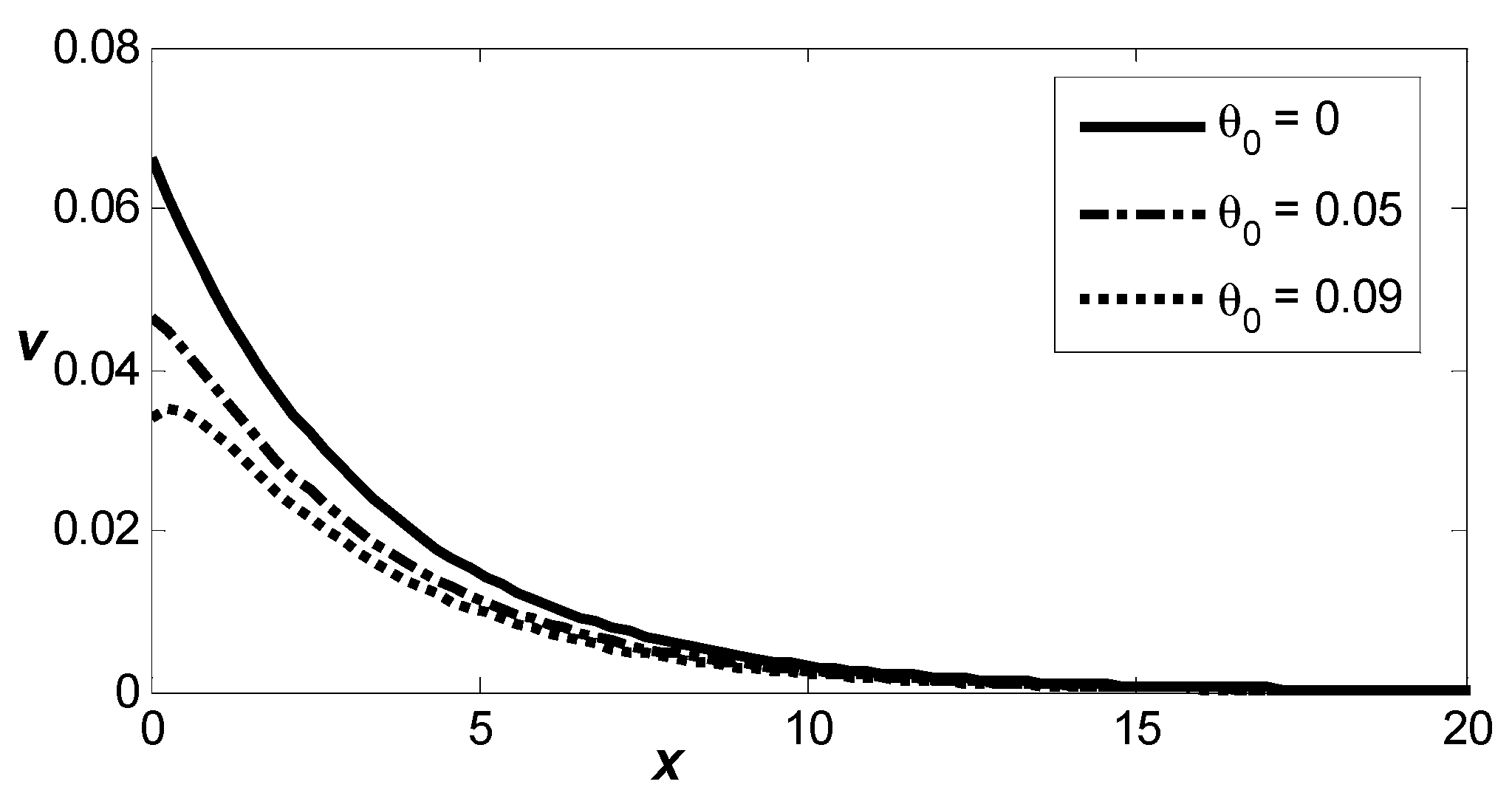

Figure 10 presents the spatial distribution profile of the vertical displacement component,

, in a thermoelastic medium influenced by varying values of the reference temperature. For all values of the reference temperature

all curves show a significant downward displacement near the surface, with a smooth decline toward zero as the distance,

, increases. It is clear that the magnitudes of

where

predict slightly lower displacement values compared to the magnitudes of

where

indicating that the reference temperature decreases the values of

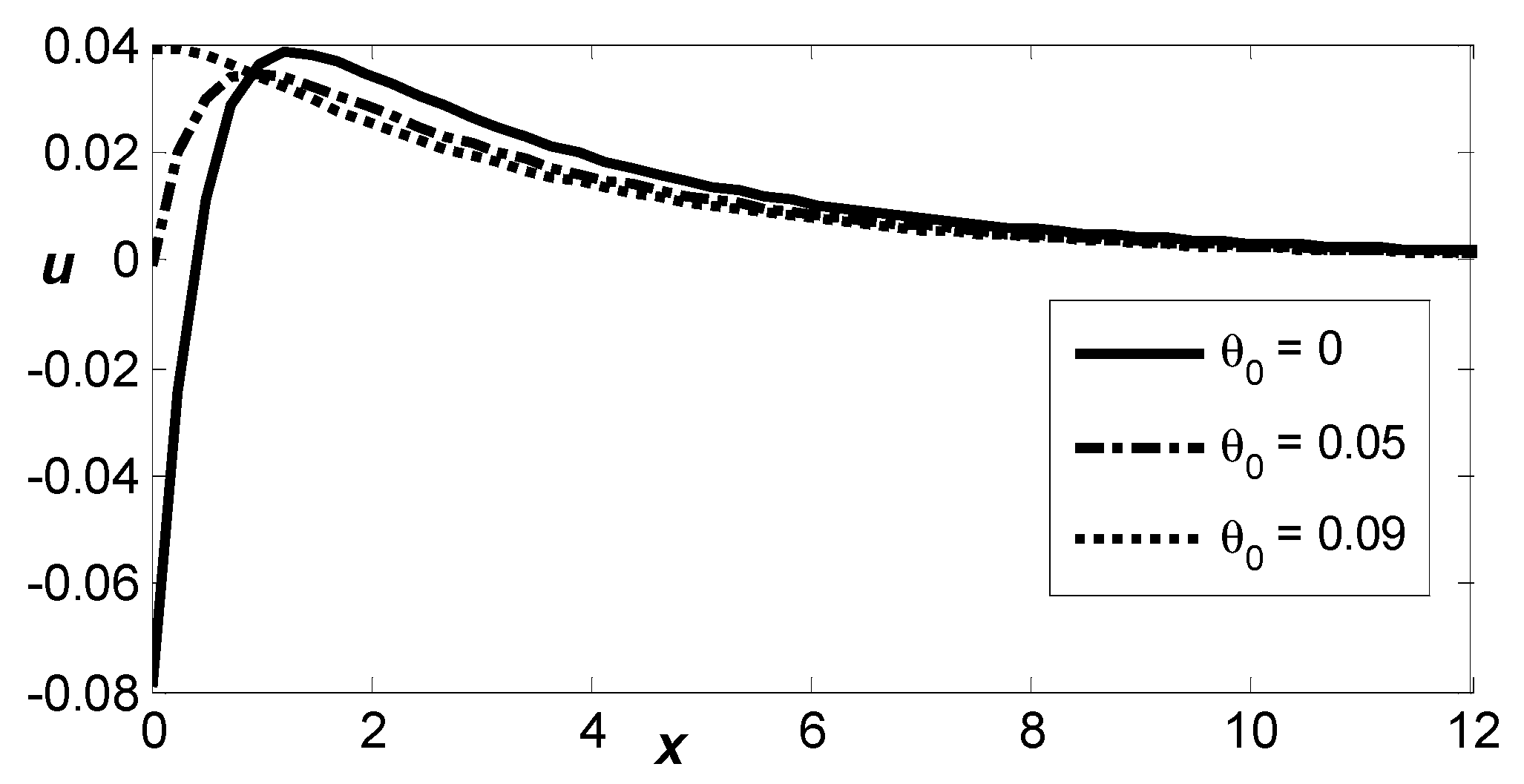

Figure 11 illustrates the spatial variation in horizontal displacement,

, in a thermoelastic medium influenced by varying the reference temperature. For all values of the reference temperature

the curves display a notable upward shift, followed by a pronounced downward shift, eventually tapering off smoothly toward zero as the distance increases. It is clear that the reference temperature,

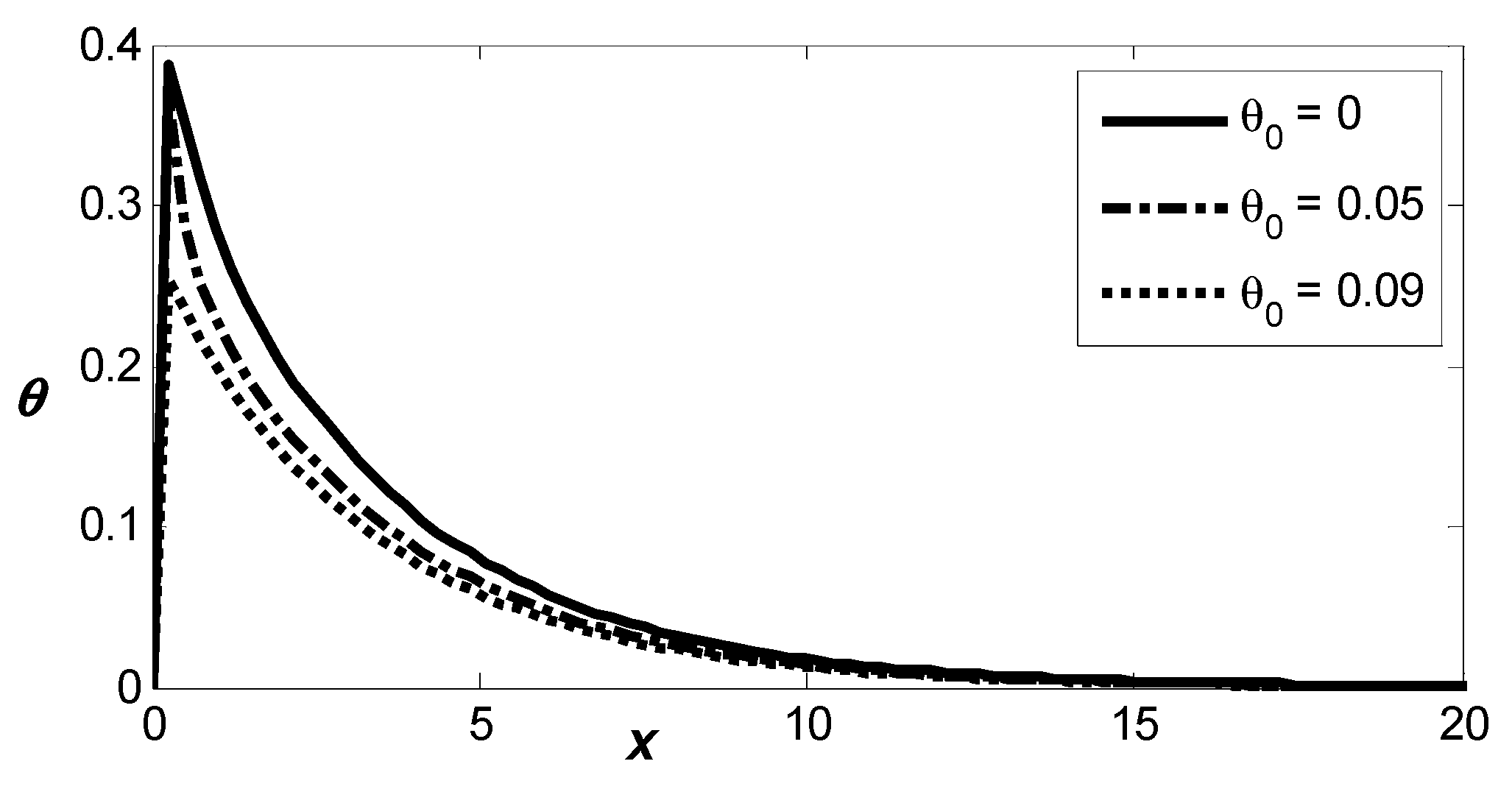

, increases, then decreases magnitudes of

Figure 12 illustrates the distribution of thermal temperature influenced by varying the reference temperature. All the curves display a notable upward shift towards the maximum value, followed by a pronounced downward shift, eventually tapering off smoothly toward zero as the distance increases. It is obvious that the magnitudes of

where

predict slightly lower magnitudes compared to the values of

where

indicating that the reference temperature decreases the magnitudes of

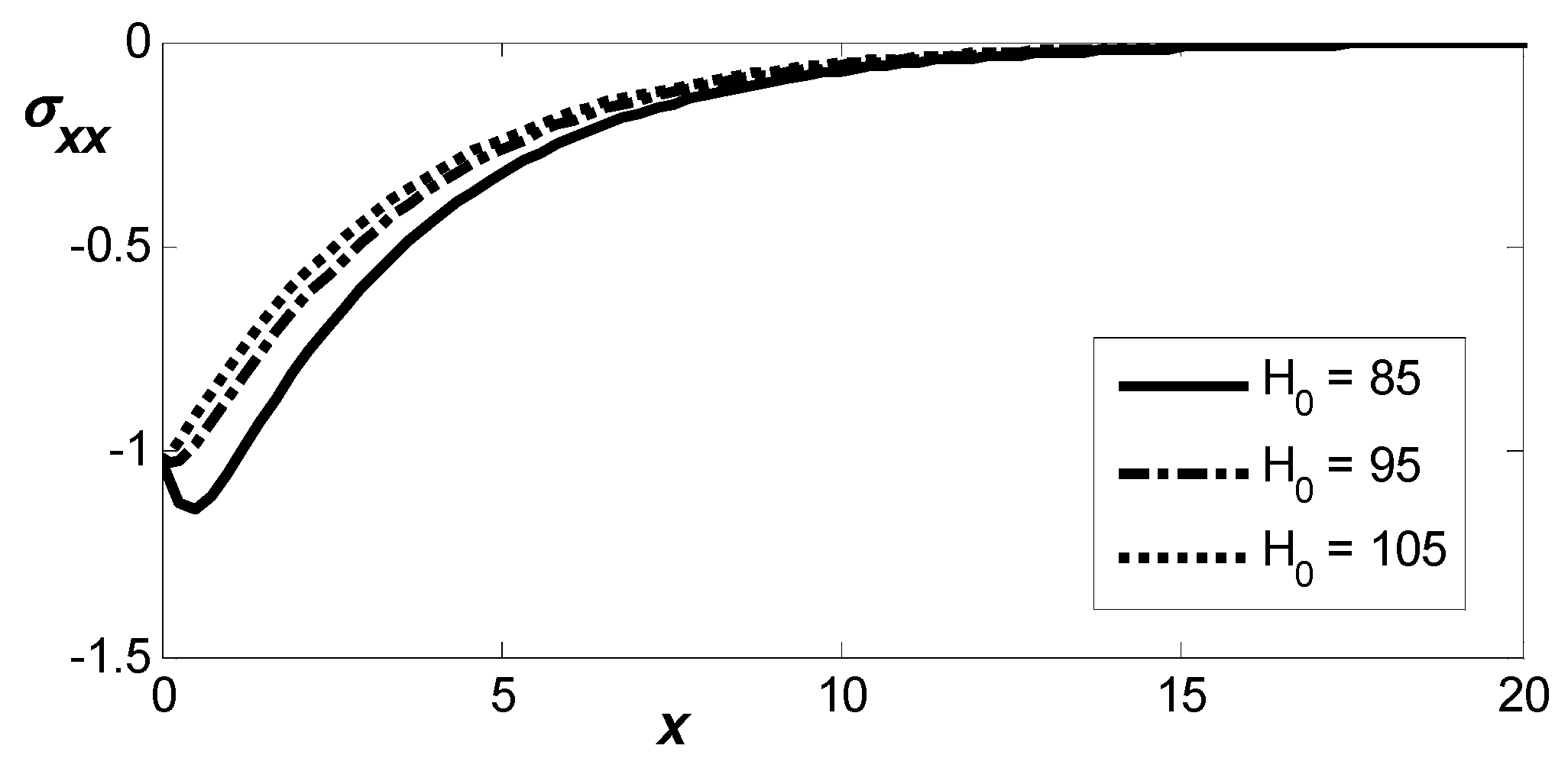

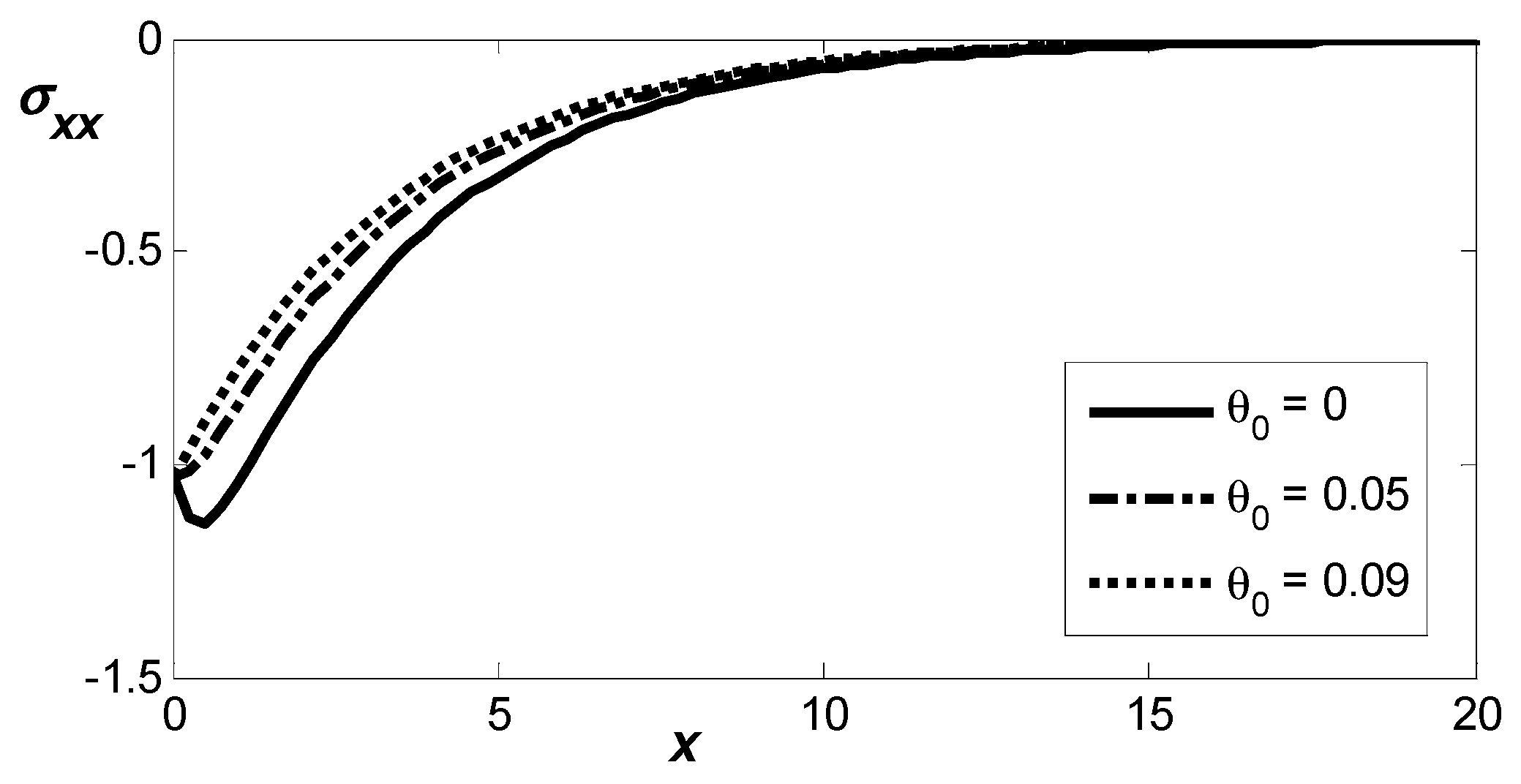

Figure 13 illustrates how the spatial distribution of the normal stress component,

, varies with varying reference temperature. All the curves depict an increasing in the interval

followed by a gradual recovery toward zero as

increases. It is obvious that the magnitudes of

where

predict slightly higher magnitudes compared to the values of

where

indicating that the reference temperature increases the values of

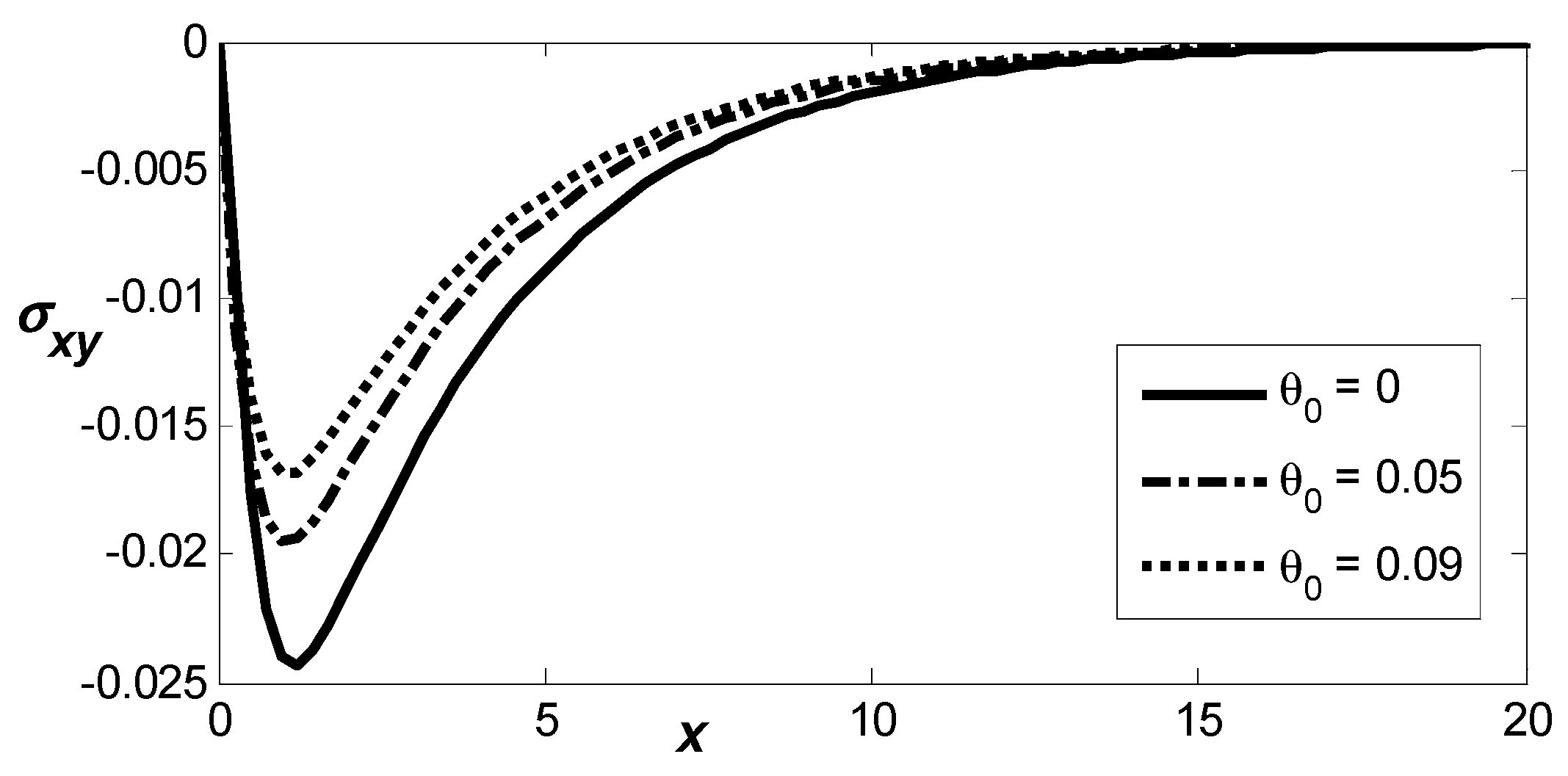

Figure 14 illustrates the distribution of the shear stress component,

, relative to the spatial variable, highlighting the influence of the reference temperature. The magnitudes of

decrease crisply to a minimum magnitude, then crisply increase, and then gradually relax toward zero. It can be observed that an increase in the reference temperature leads to higher corresponding values of

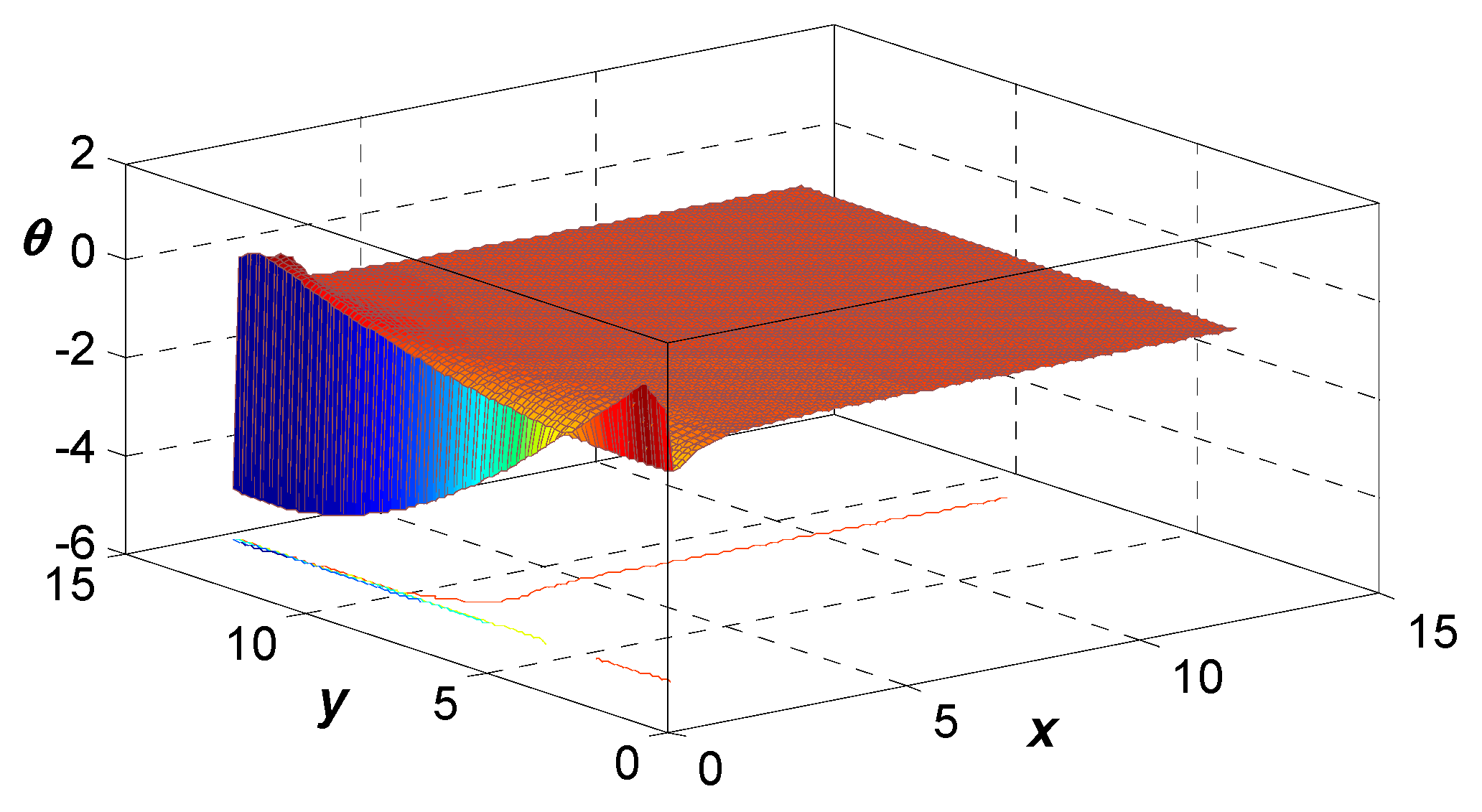

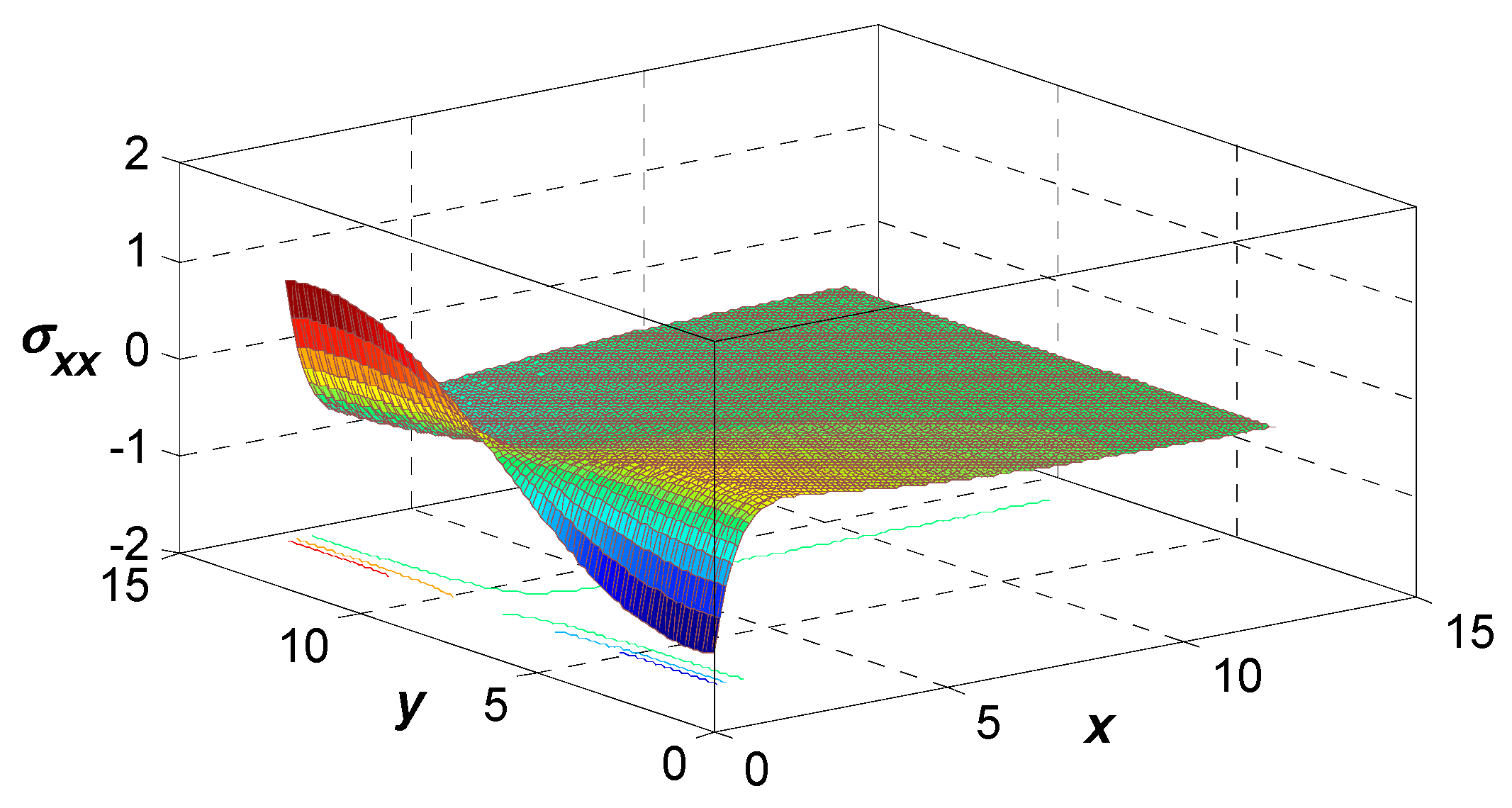

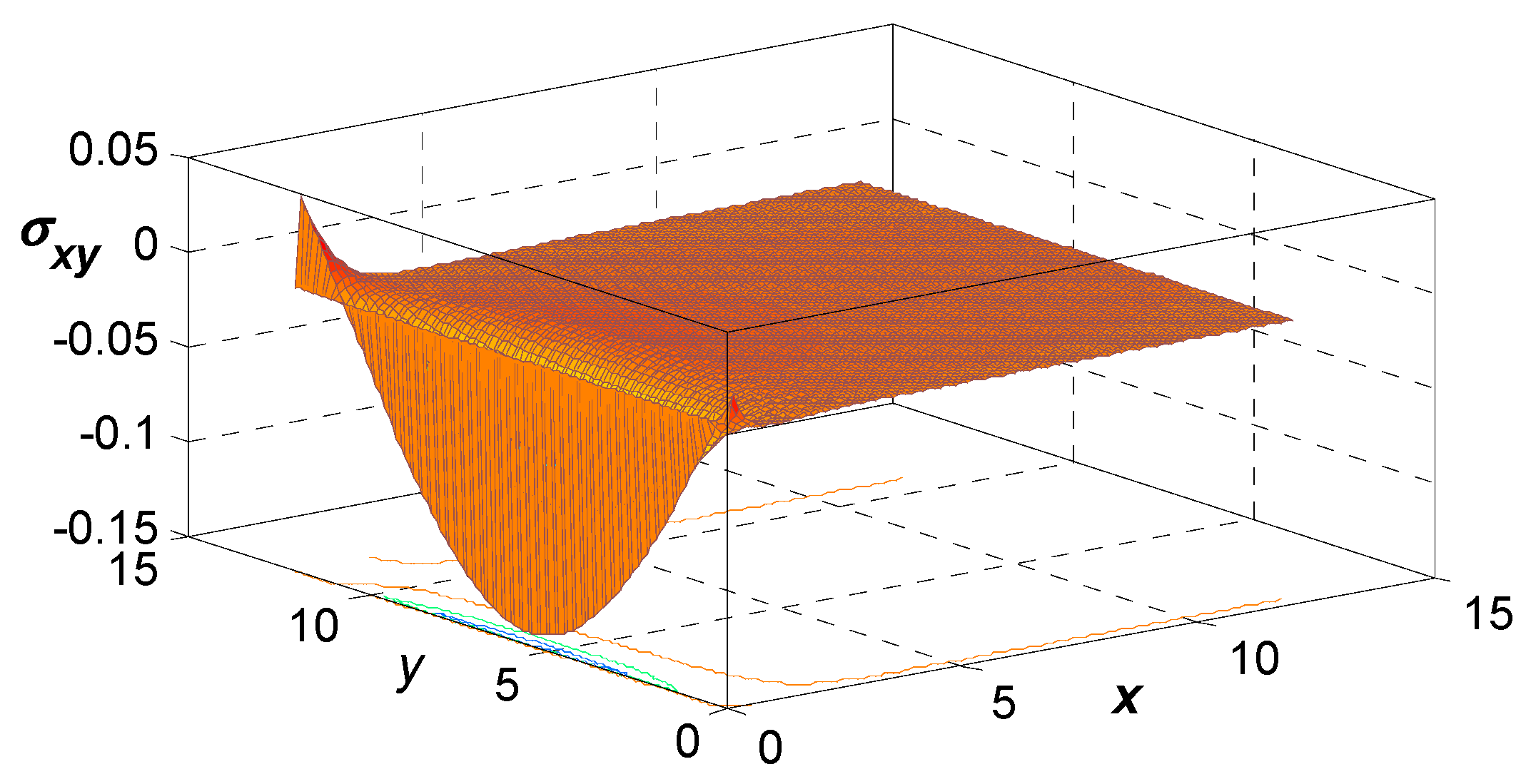

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 entertain 3D surface curves for

via the 3PHL G-N III framework. The upshot of the magnetic field and reference temperature for wave propagation in a thermoelastic solid was explained. These figures are really helpful for treating the addiction of these physical variables to the vertical distance.