Artificial Neural Network-Based Optimization of an Inlet Perforated Distributor Plate for Uniform Coolant Entry in 10 kWh 24S24P Cylindrical Battery Module

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Method

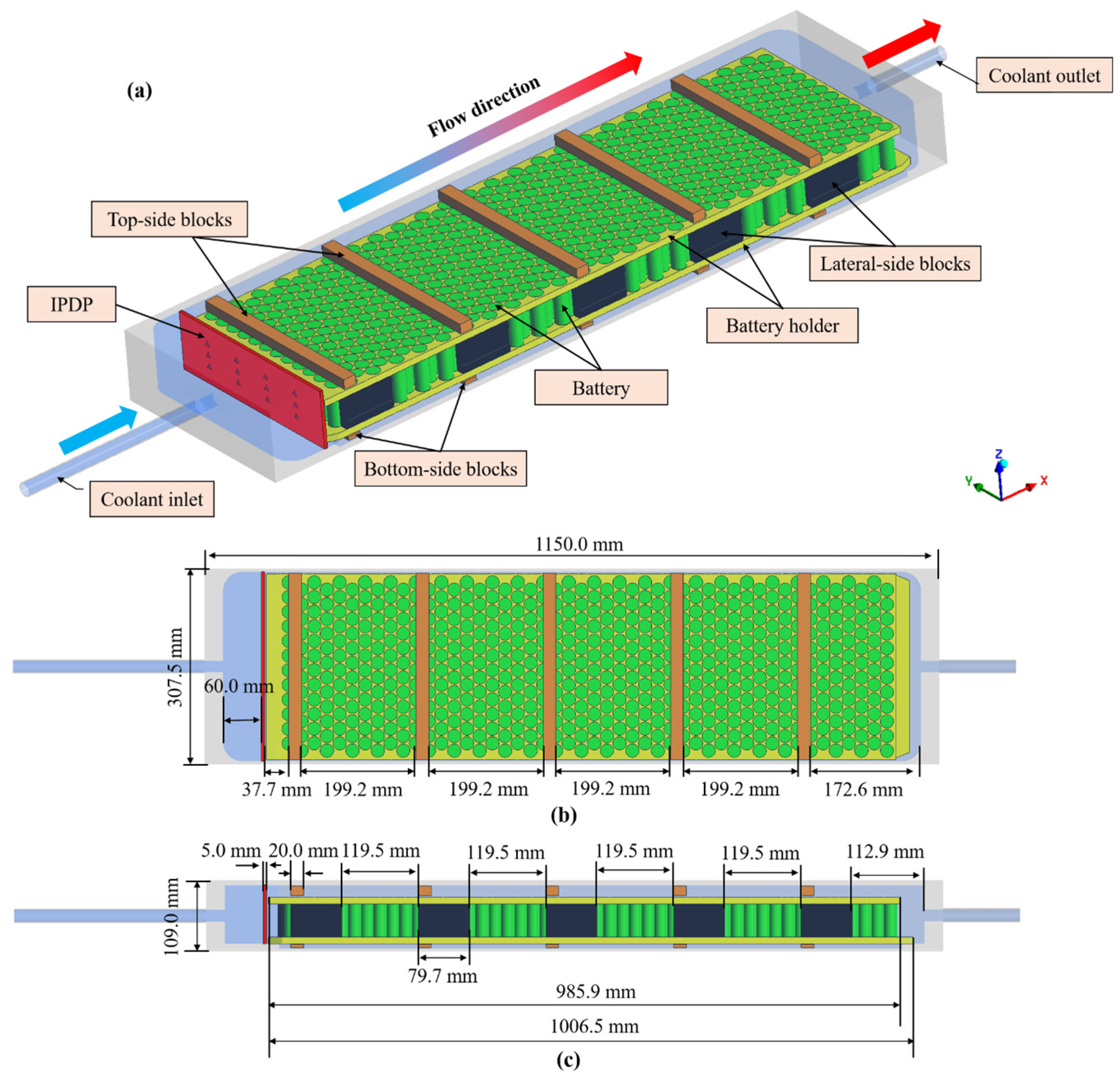

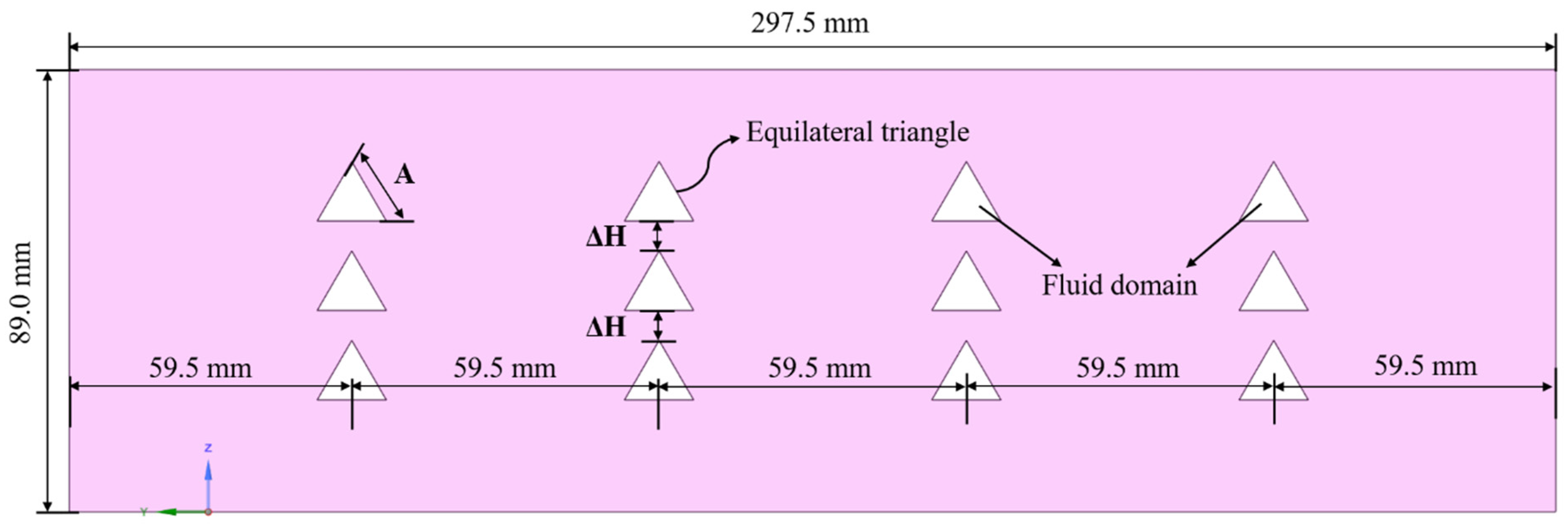

2.1. Computational Geometry

2.2. Battery Heat Generation and Coolant Modeling

2.3. Boundary Conditions

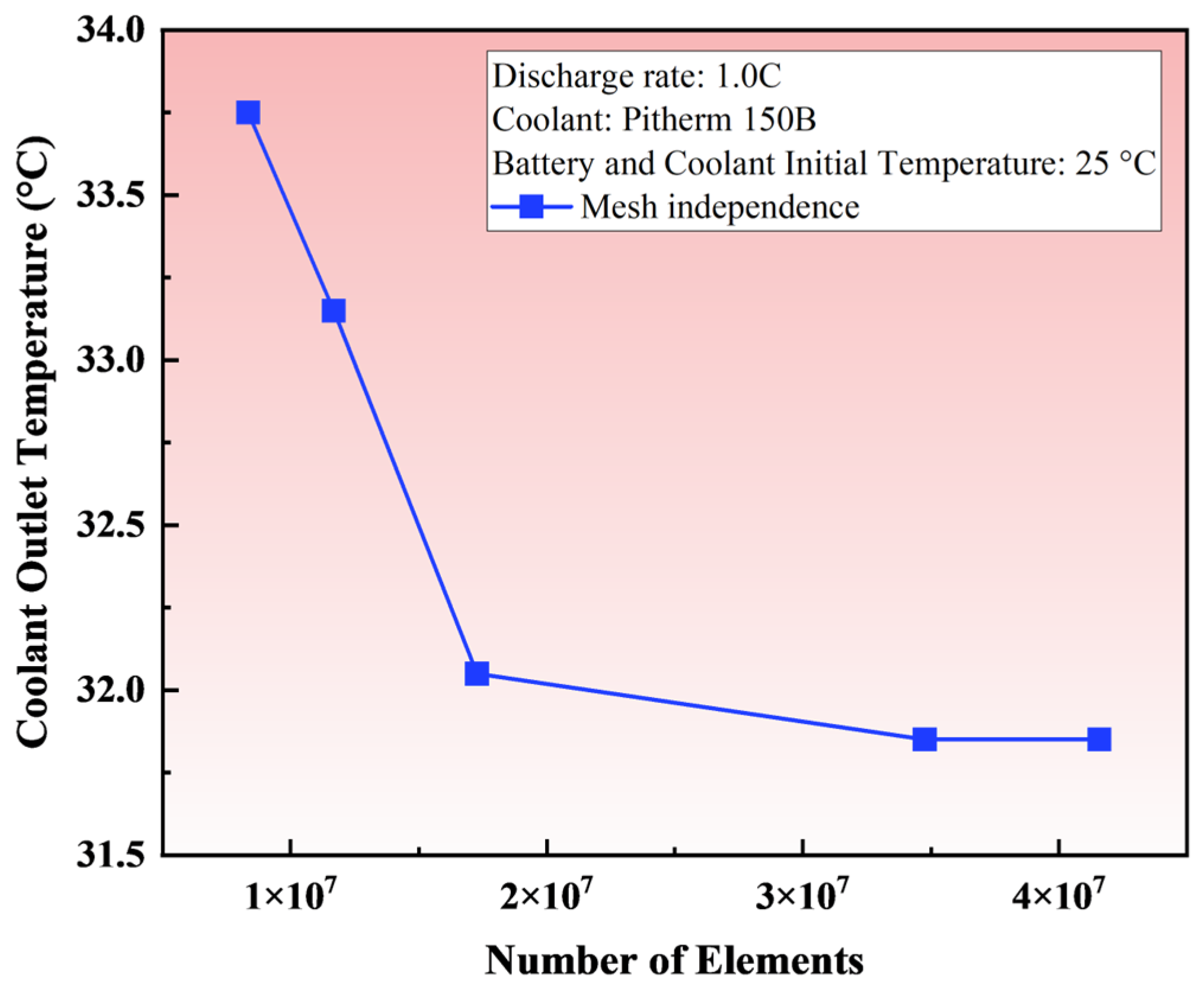

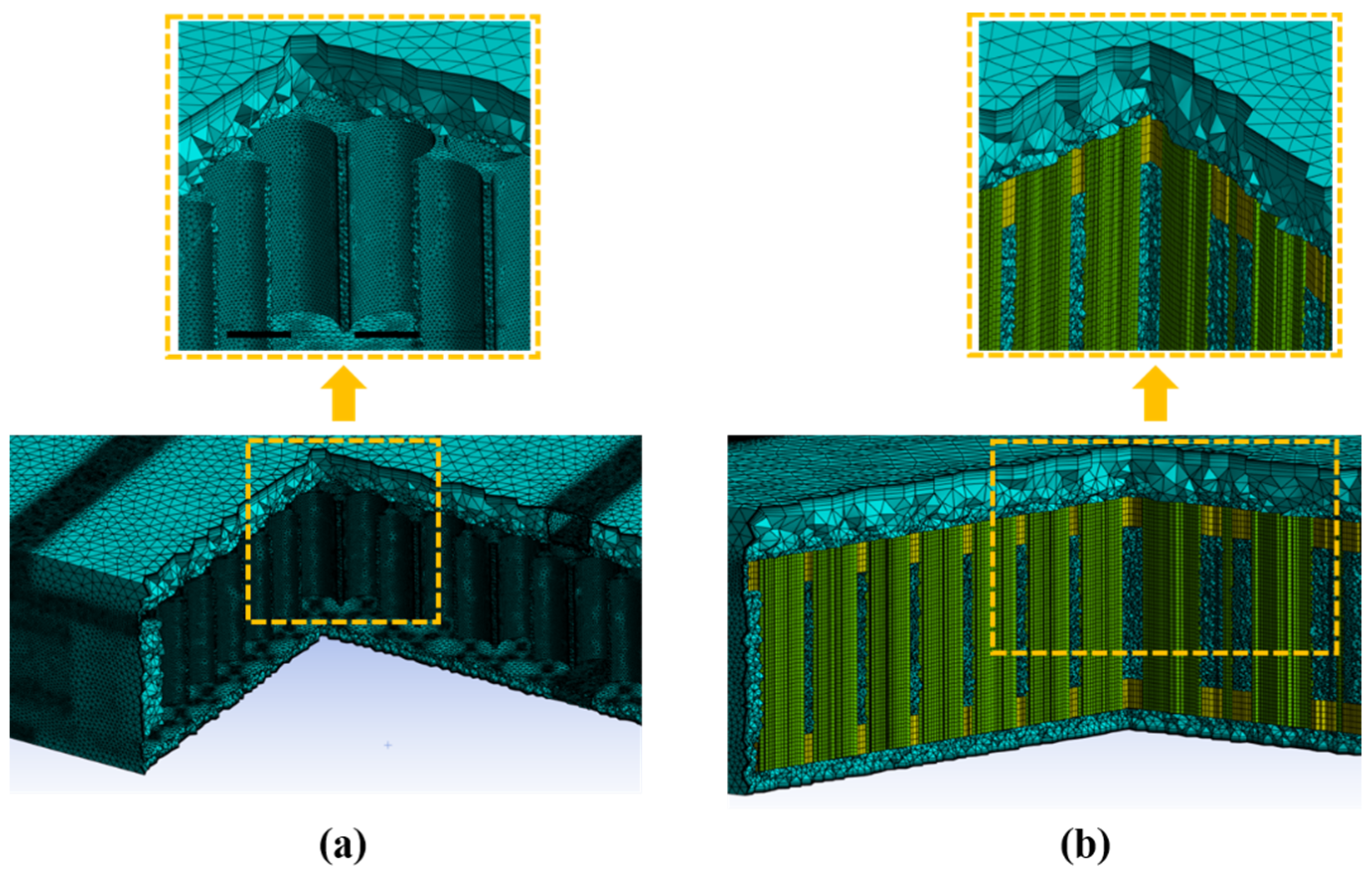

2.4. Mesh Independence Verification

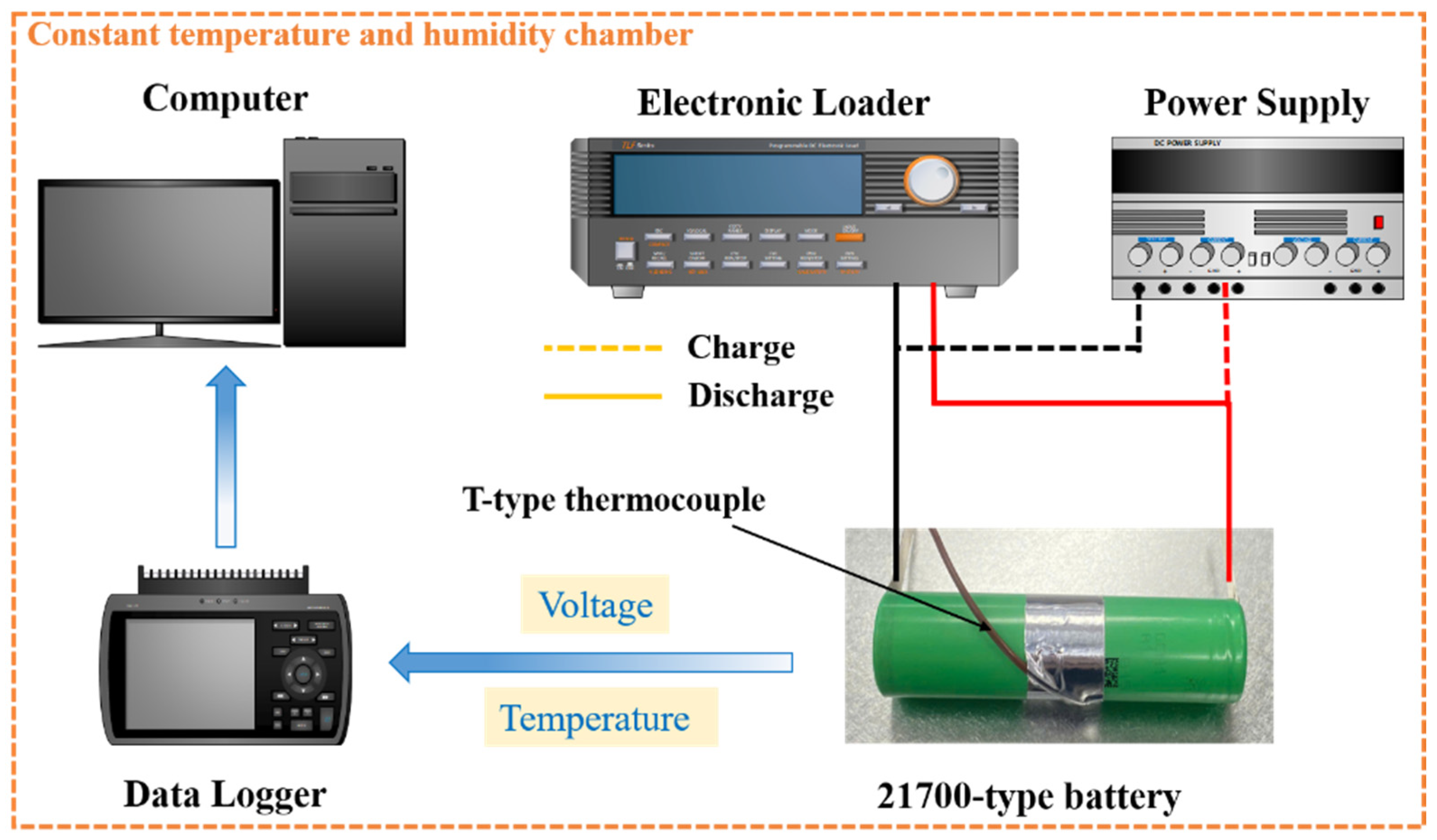

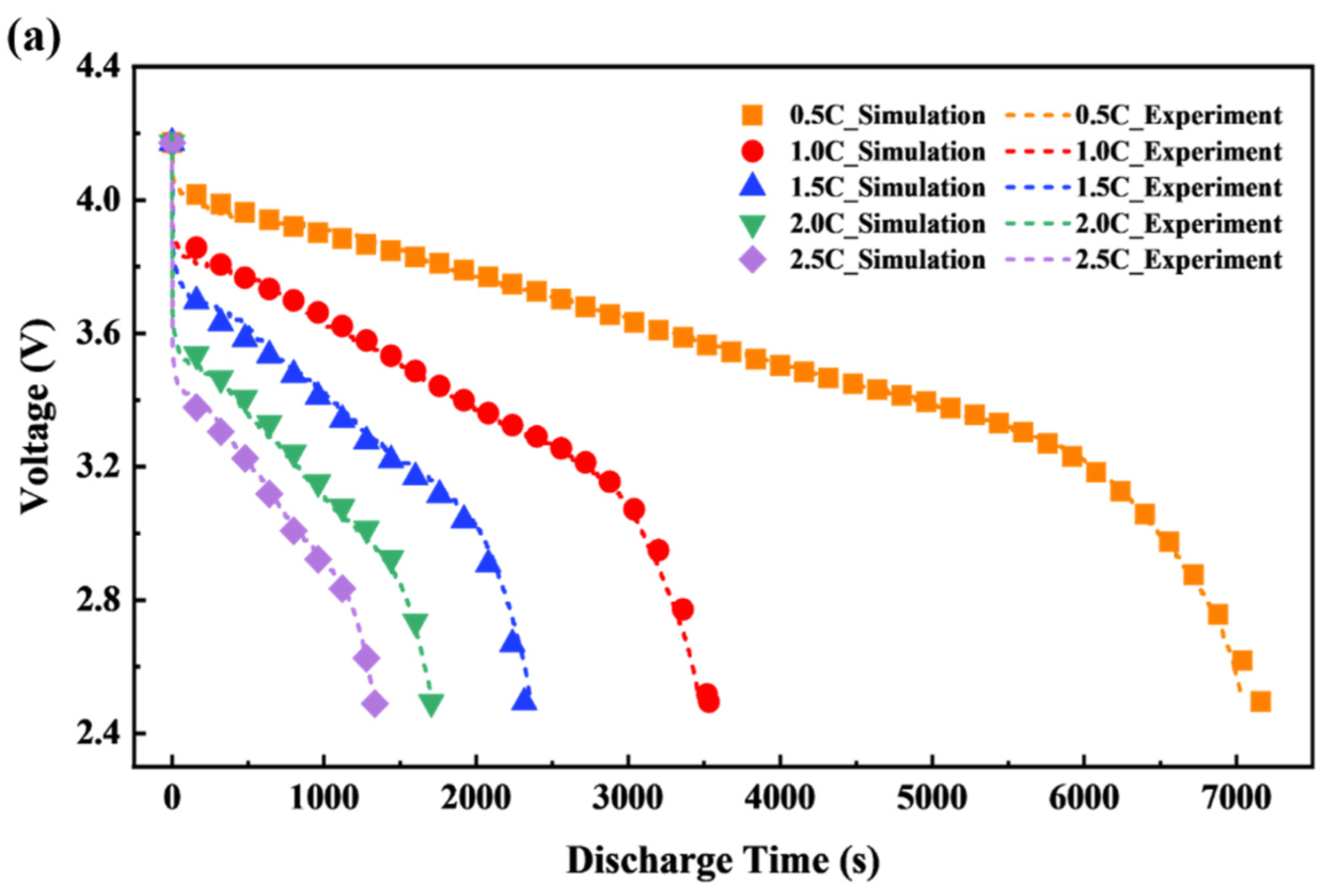

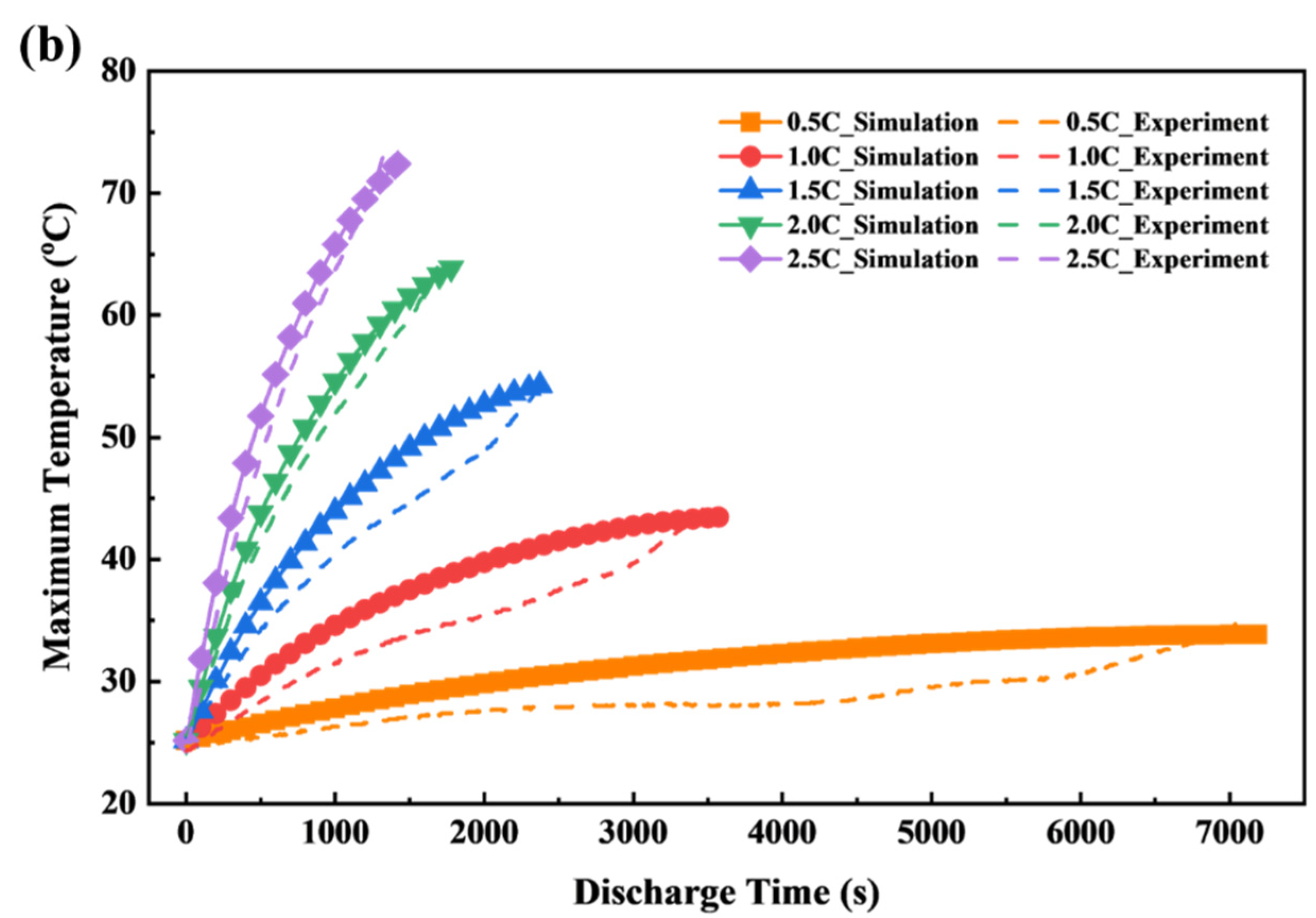

2.5. Validation

3. Results and Discussion

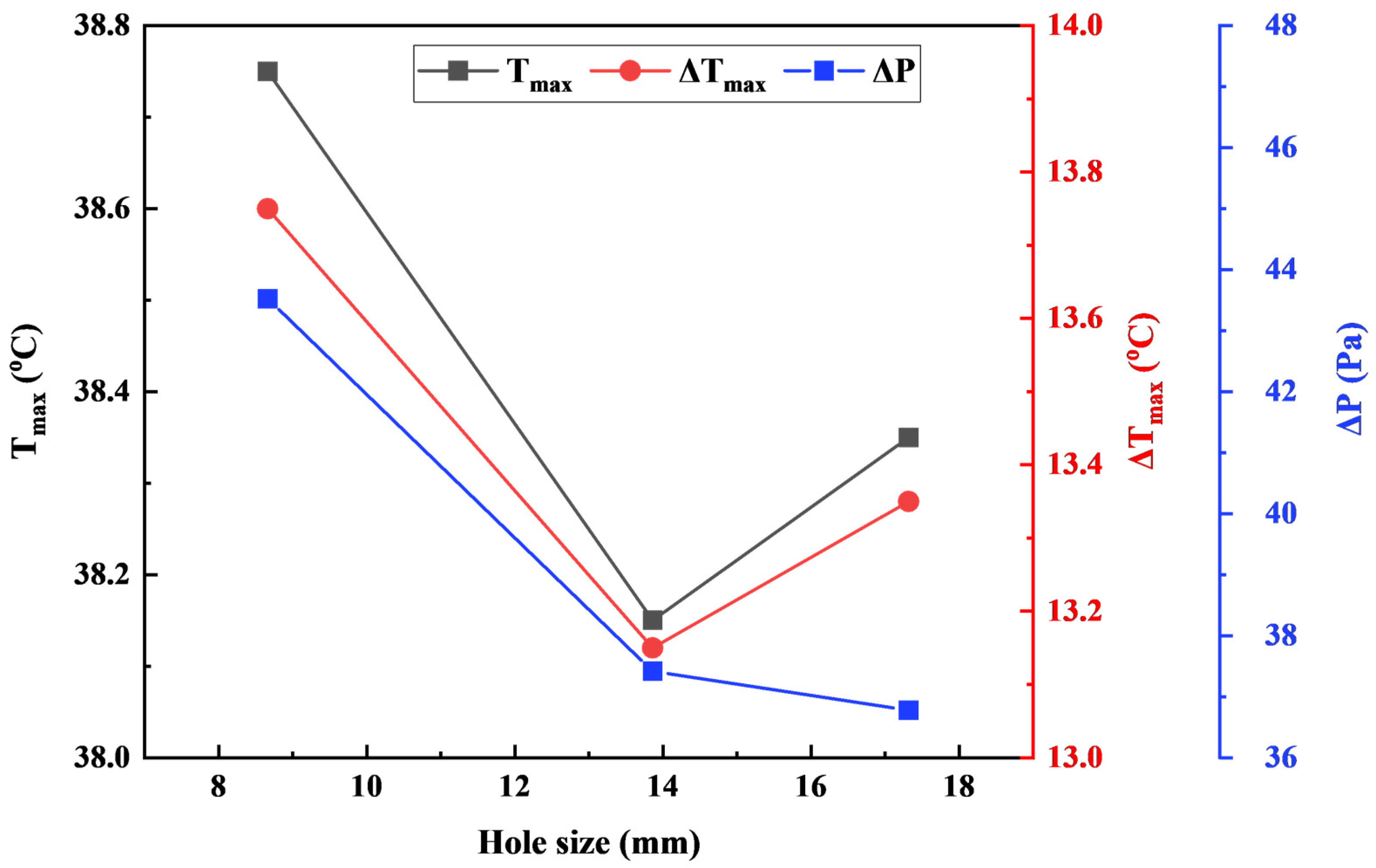

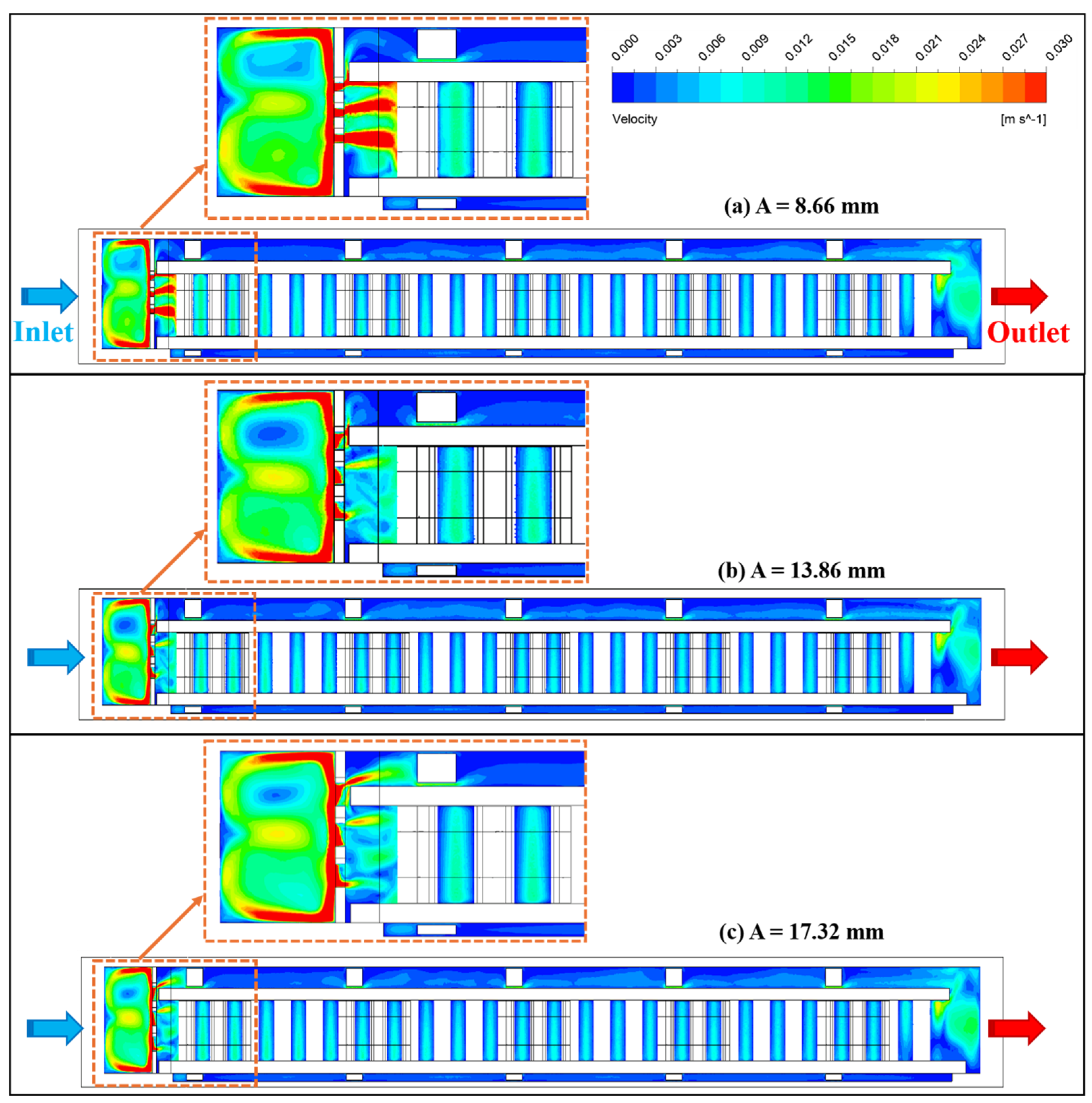

3.1. Effect of the Hole Size A

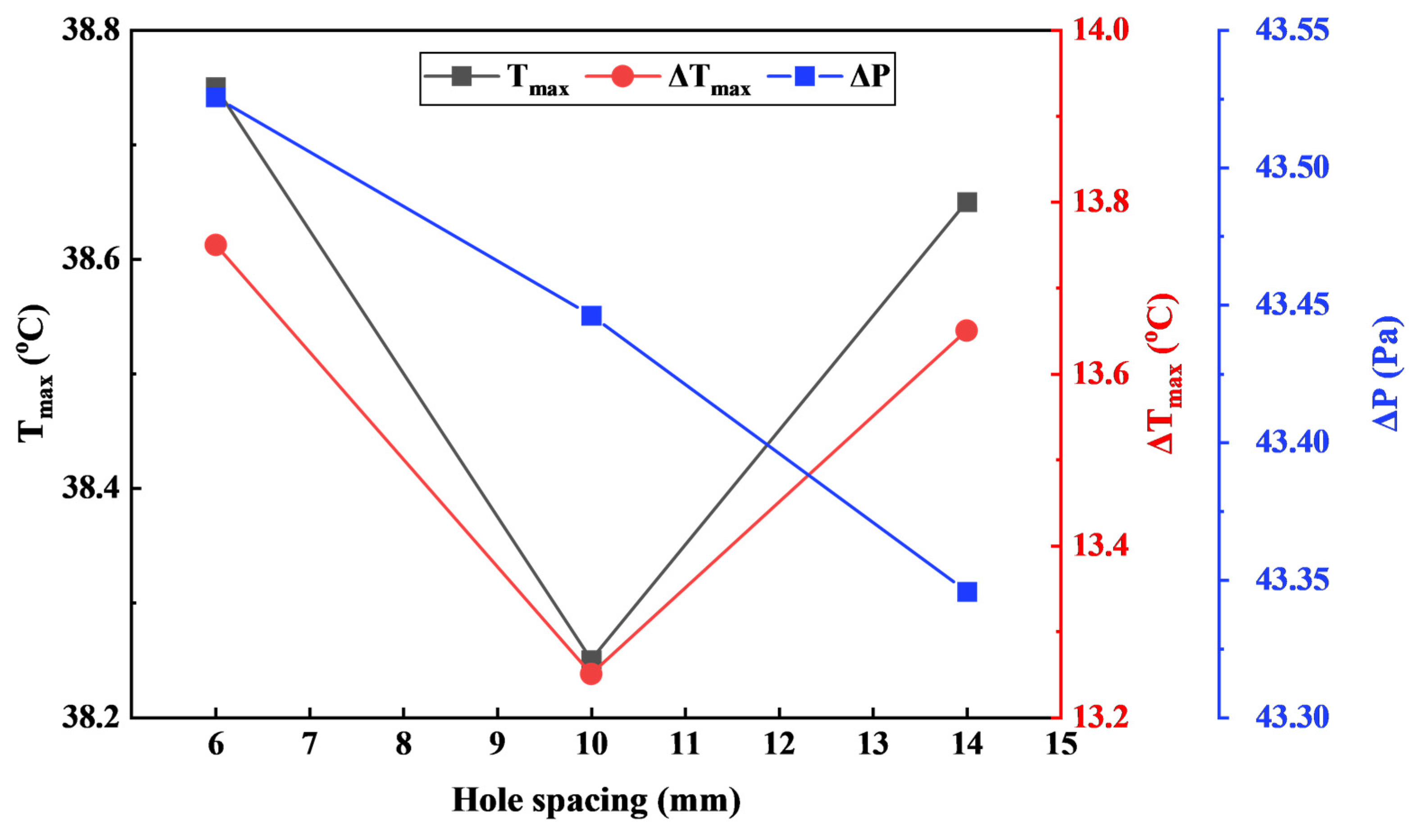

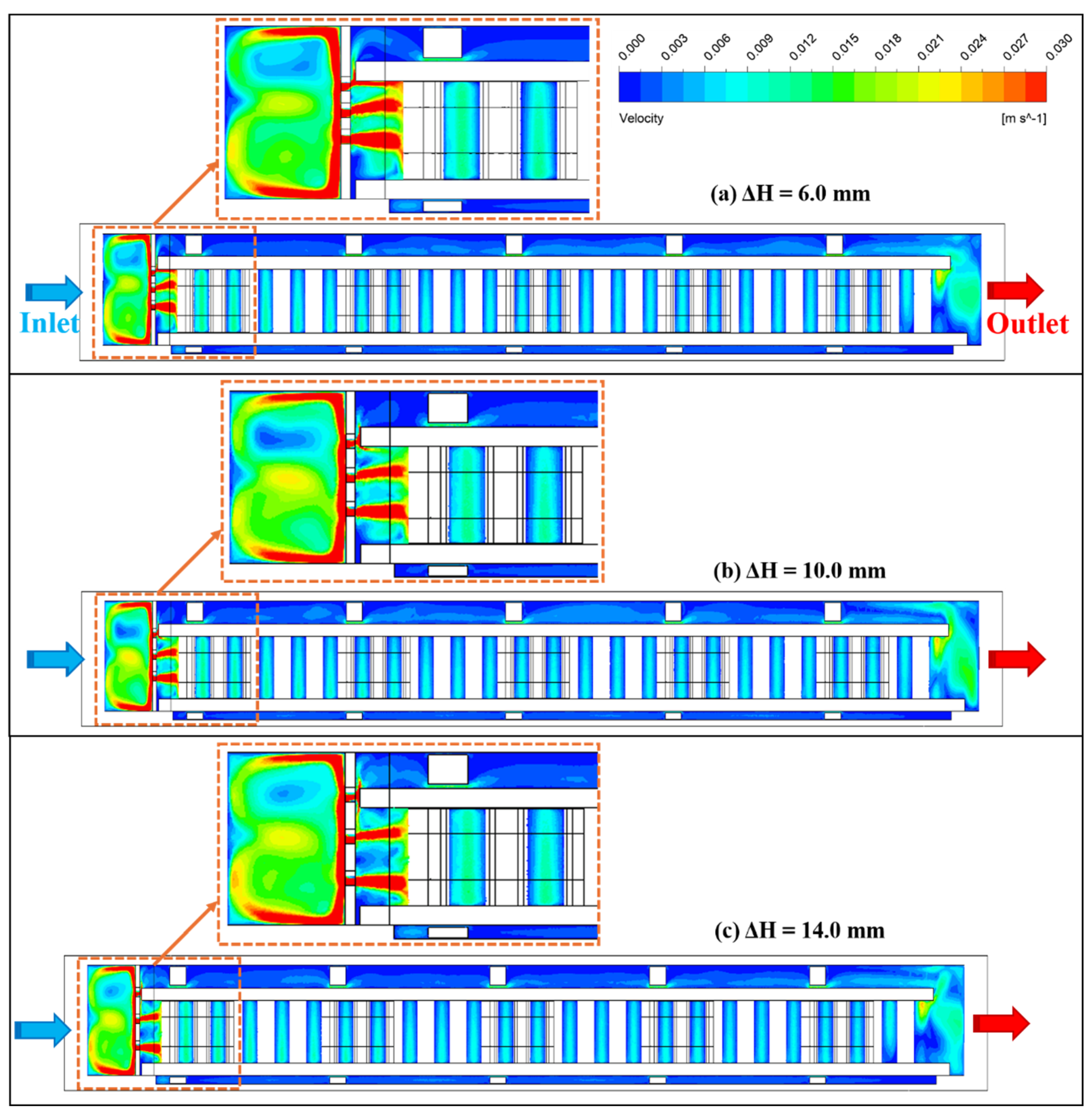

3.2. Effect of the Hole Spacing ΔH

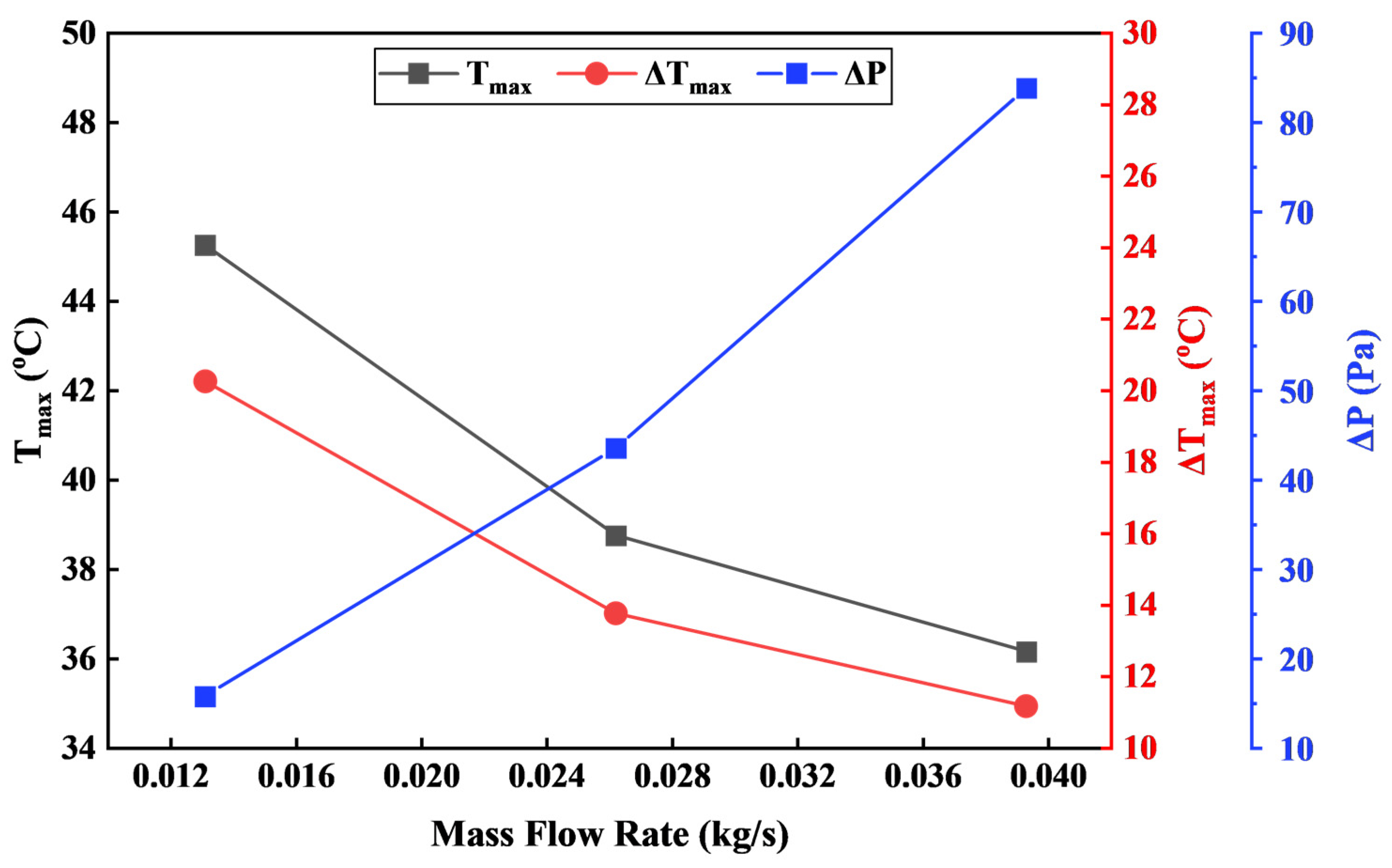

3.3. Effect of the Coolant Mass Flow Rates Vin

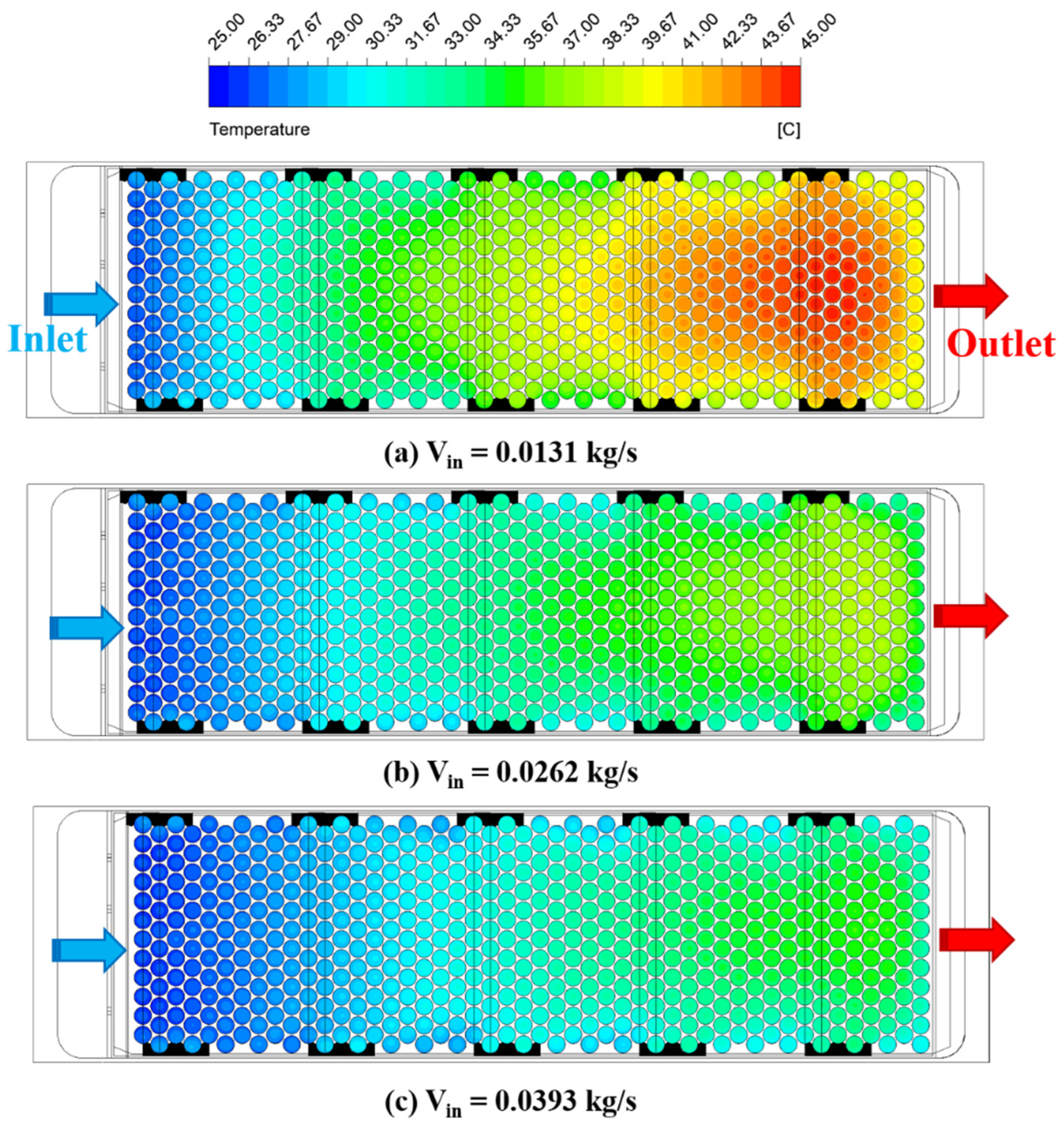

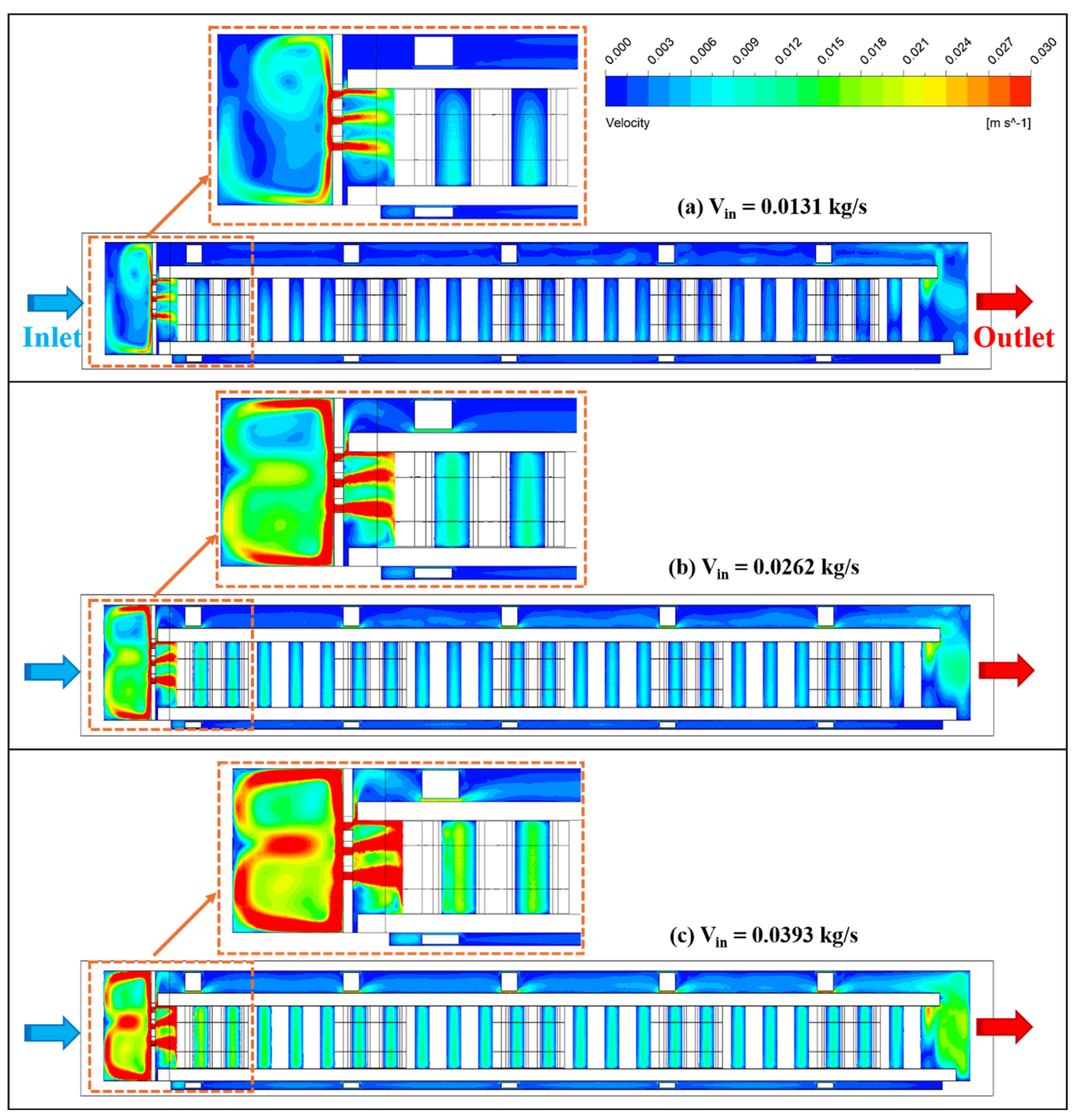

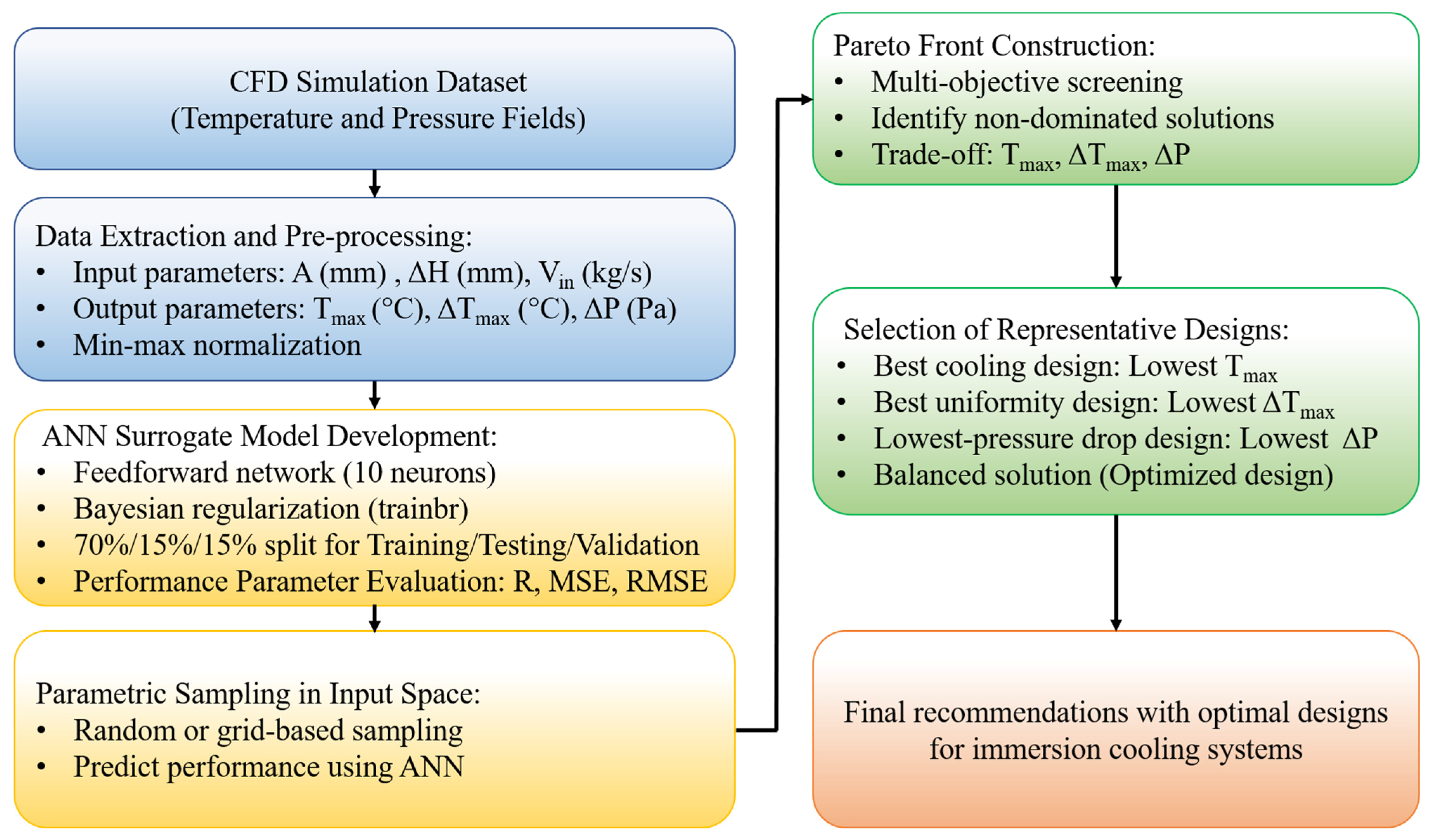

3.4. Multi-Objective Optimization

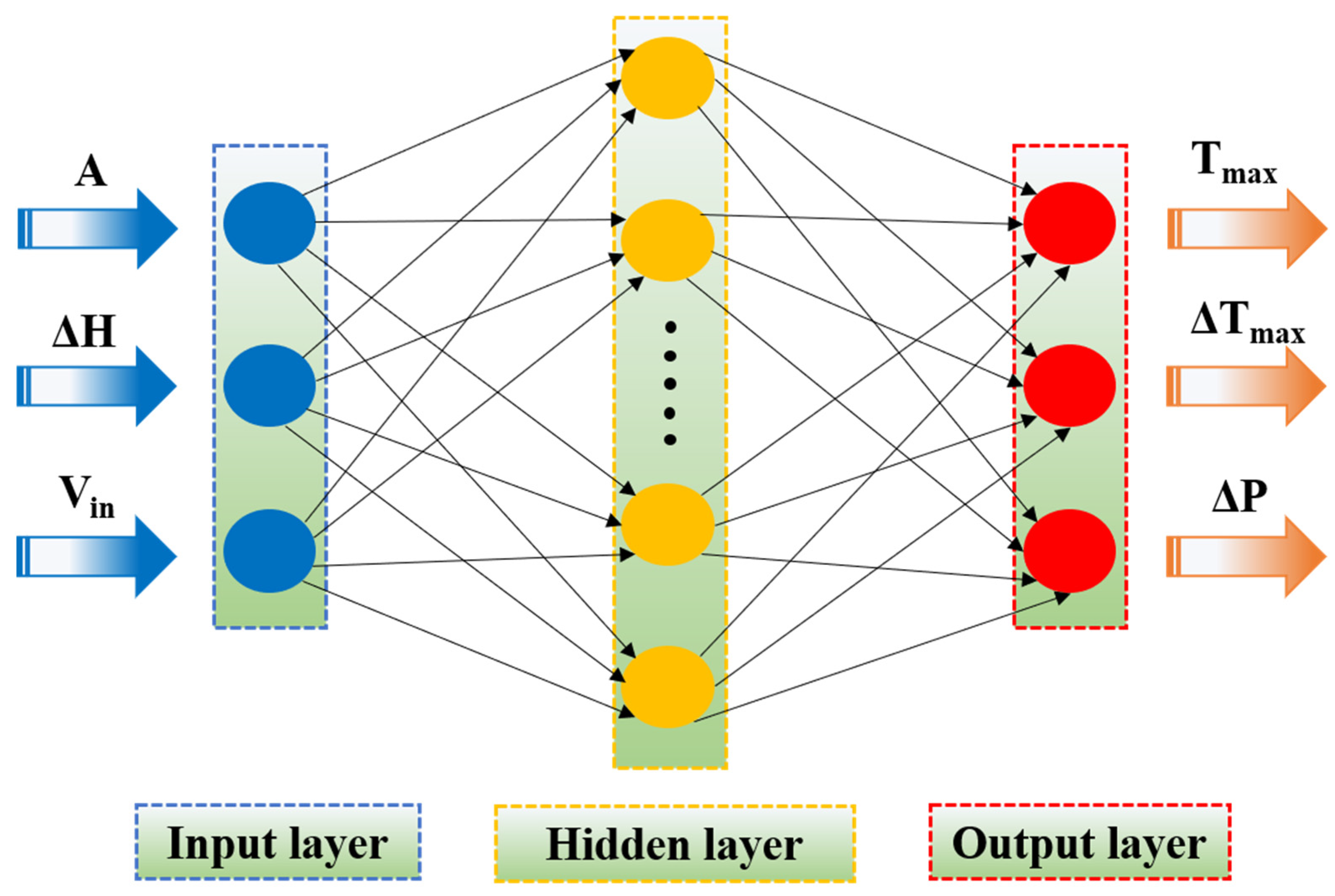

3.4.1. ANN Structure

3.4.2. Machine Learning Training and Prediction

3.4.3. Optimized Results and Validation

4. Conclusions

- (a)

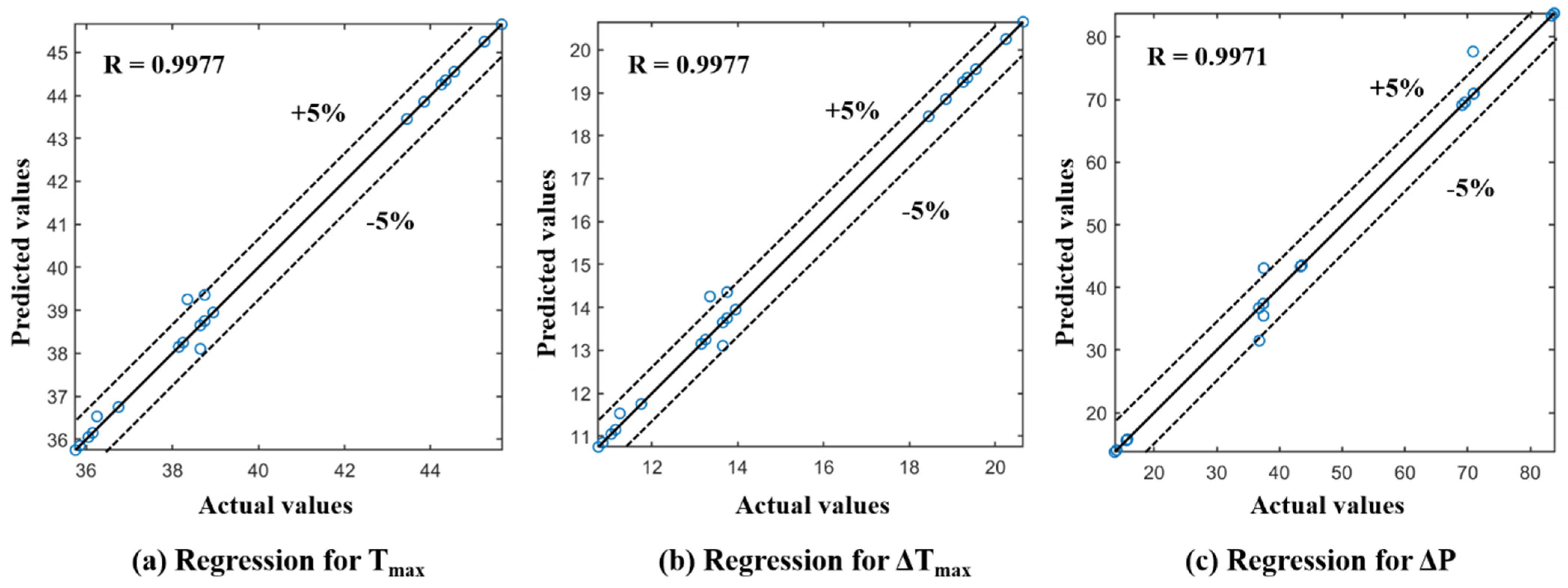

- The results of the study show that the generated dataset allows training a highly accurate ANN model, capable of predicting Tmax, ΔTmax, and ΔP with strong correlations with CFD simulation results. Specifically, a correlation coefficient R of 0.9977 with an RMSE value of 0.24 °C was achieved for the Tmax and ΔTmax variables. Additionally, the ΔP prediction also showed high accuracy with an R of 0.9971 and a RMSE of 2.01 Pa.

- (b)

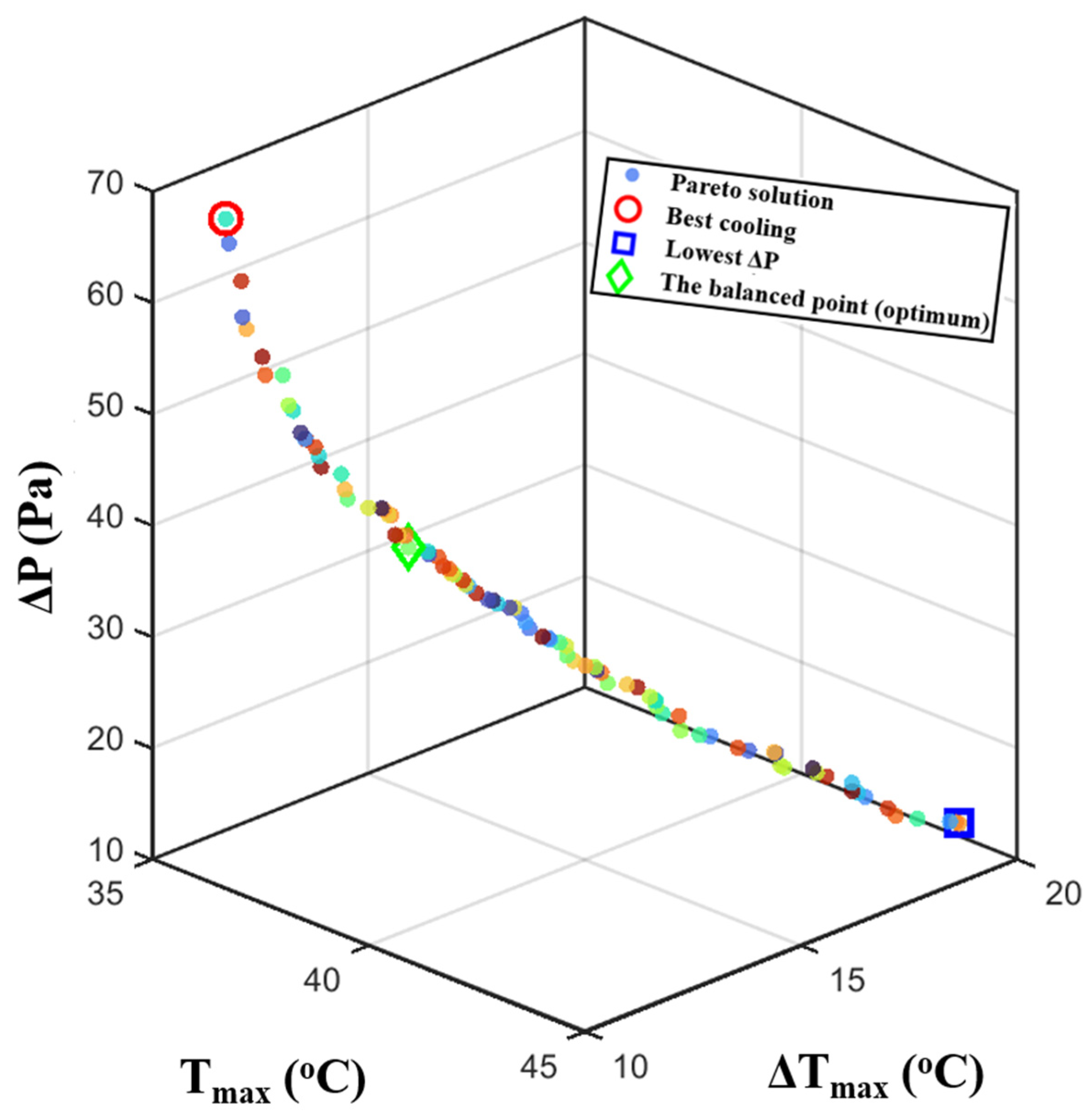

- Parametric analyses revealed a clear interaction between geometric parameters and flow characteristics, highlighting the trade-off between cooling efficiency and hydraulic losses. Multi-objective optimization identified Pareto-optimal configurations that simultaneously minimized hot spot formation and ΔP, demonstrating that tailoring the hole geometry and coolant mass flow rate Vin can significantly improve cooling efficiency without causing excessive pumping power.

- (c)

- The optimized design achieved significant improvements in thermal performance in the battery module with Tmax maintained within the optimal range at 37.97 °C and a significant reduction in ΔP of up to 44%, illustrating the potential of data-driven optimization for next-generation battery thermal management systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- You, N.; Chinnasamy, V.; Lee, M.; Cho, H. Correlation analysis between design parameters and cooling performance in 21700 battery module using immersion cooling. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 68, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tao, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. Recent advances in immersion cooling for thermal management of lithium-ion batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 226, 116492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedari Salehzadeh, F.; Heyhat, M.M. Direct and indirect cooling of Lithium-ion batteries with new manifold designs. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 68, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Li, X. Preference for electric vehicles among young adults: A discrete choice analysis in China. Transp. Policy 2025, 175, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.D.; Garud, K.S.; Hwang, S.; Lee, M. A Review on Advanced Battery Thermal Management Systems for Fast Charging in Electric Vehicles. Batteries 2024, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Q.; Hou, Z.; Liu, J. Cooling effectiveness of the immersion cooling on the overcharging lithium-ion batteries. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 68, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Kong, D.; Ping, P.; Zhao, X.; Dai, X.; Ren, J.; Ren, X.; Guo, J. Synthetic ester immersion cooling for lithium-ion batteries: A comparison of electro-thermal balancing under static and dynamic conditions and heat transfer analysis. J. Energy Storage 2025, 141, 119072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.D.; Garud, K.S.; Lee, M. Experimental Study on Thermal Management of 5S7P Battery Module with Immersion Cooling Under High Charging/Discharging C-Rates. Batteries 2025, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Park, S.-Y. Computational Analysis for Efficient Battery Cooling for Electric Vehicles Using Various Cooling Methods. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2025, 26, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Chen, Y.; Cai, L.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Z. Performance of lithium-ion battery cooling plates based on topology optimization and bionic design. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2026, 284, 129168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.D.; Lee, M. Advances in the Battery Thermal Management Systems of Electric Vehicles for Thermal Runaway Prevention and Suppression. Batteries 2025, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, D.; Xi, H. Numerical investigation for a coupled fin-PCM-liquid cooling system under multi-scenario of thermal management and thermal runaway mitigation in lithium-ion battery modules. J. Energy Storage 2025, 140, 119078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-H.; Ma, B.-C. Optimization of thermal management for immersion cooled lithium-ion batteries based on experimental design methods. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2025, 26, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Ting, Y.; Chang, C.M.; Huang, C. Thermal management analysis of fast-charging lithium-ion battery packs: Effects of cooling strategies. Next Energy 2025, 9, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaoui, S.; Sabatier, J.; Vinassa, J.; Guillemard, F. Research and implementation of a fast-charging methodology for lithium-ion batteries under bottom and dual cooling configurations. J. Energy Storage 2025, 130, 117285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, R.; Wu, X.; Qiu, H.; Wu, T. Numerical simulation study on optimizing the temperature characteristics of jet fires in forced air-cooled 18650 battery modules during thermal runaway. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 76, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lyu, P.; Han, X.; Li, M.; Rao, Z. Multi-directional synergistic effects of air-cooling and liquid-cooling on the thermal runaway propagation of lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, K.S.; Tai, L.D.; Hwang, S.; Nguyen, N.; Lee, M. A Review of Advanced Cooling Strategies for Battery Thermal Management Systems in Electric Vehicles. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, S.; Zhang, H.; Ren, C.; Hu, R.; Chen, Z. Synergy of high-efficiency passive protective nanocomposite materials and active liquid cooling for suppressing thermal diffusion in lithium-ion power batteries. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 24, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqteen, M.A.; Moon, S.; Kim, J.S. A novel spray-based immersion cooling for Li-ion batteries: An experimental comparison with flow immersion. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 282, 128873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed Elfeky, K.; Hosny, M.; Mohammed, A.G.; Wang, Q.; Ge, K. Performance assessment of a novel hybrid cooling design for battery thermal management systems. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 76, 107393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, K.; Lai, X.; Xu, C.; Ben-Marzouk, M.; Meng, X. Multi-condition simulation and thermal management enhancement of a rectangular-case lithium-ion battery module single-phase immersion cooling system. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2026, 221, 110467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-H. Air-Cooled Battery Cooling Simulation Techniques Using Simulink and Simscape. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2025, 26, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhang, H. Cooling performance optimization of a novel L1−i−j-type structure for the forced air-cooled battery thermal management system. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2025, 117, 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, H.M.; Abdulwahab, M.R.; Almohammed, O.A.M.; Abed, A.M.; Al-attab, K.A.; Abdullah, M.Z.; Enagi, I.I. Effectiveness of indirect evaporative cooling in battery thermal management systems based on a novel heat pipe structure: An experimental study. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardımcı, U.; Tuğan, V. Computational fluid dynamics analysis of battery pack with cooling channel integrated with innovative thermoelectric cooling stations. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2026, 220, 110380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.-H.; Kim, T.-W.; Kim, M.-J.; Yu, J.-S.; Hong, D.-S. Experimental Study on the Thermal Characteristics and Melting Behavior of Phase Change Materials Applied to the Cooling System of Electric Vehicle Chargers. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2024, 25, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Yang, W.; He, P.; Zhang, X. Performance analysis and optimized design of hybrid battery thermal management system integrating leak-free PCM with liquid cooling under extreme temperature conditions. Energy 2025, 341, 139404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Ding, J.; Liu, L. Numerical investigation on the cooling performance of lithium-ion battery using liquid cooled-plate with integrated grooves and secondary microchannel structures. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 217, 110094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yuan, N.; Kong, B.; Zou, Y.; Shi, H. Simulation of hybrid air-cooled and liquid-cooled systems for optimal lithium-ion battery performance and condensation prevention in high-humidity environments. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 257, 124455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, S. A liquid cooling plate based on topology optimization and bionics simplified design for battery cooling. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 114171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Yang, J.; Yang, P.; Zhang, H.; Cai, T. Optimization and working performance analysis of liquid cooling plates in refrigerant direct cooling power battery systems. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 231, 125899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Qin, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; Zhou, X. Performance optimization of two-phase immersion cooling systems for large-format lithium-ion battery packs. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.Y.; Muhieldeen, M.W.; Teng, K.H.; Ang, C.K.; Lim, W.H. A novel thermal management system for lithium-ion battery modules combining indirect liquid-cooling with forced air-cooling: Deep learning approach. J. Energy Storage 2024, 94, 112434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hong, X.; Huo, Z.; Ruan, D. Enhancing lithium-ion battery cooling efficiency through leaf vein-inspired double-layer liquid cooling plate design. J. Energy Storage 2024, 88, 111584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Xi, H. Immersion coupled direct cooling with non-uniform cooling pipes for efficient lithium-ion battery thermal management. J. Energy Storage 2025, 116, 116010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Kong, B.; Zeng, Z.; Yuan, N.; Shi, H. Innovative coupled cooling strategy for enhanced battery thermal management: Synergistic optimization of jet impingement and immersion cooling. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 232, 125963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, W.; Wei, L.; Hu, C.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Song, Y. Numerical simulation for comparison of cold plate cooling and HFE-7000 immersion cooling in lithium-ion battery thermal management. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, A.; Bak, J.; Bhatia, B.; Park, S. Optimizing single-phase immersion cooling system for lithium-ion battery modules in electric vehicles: A multi-objective design approach. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 210, 109636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Xie, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X. Numerical study on a novel thermal management system coupling immersion cooling with cooling tubes for power battery modules. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Tong, J.; Zheng, M.; Chen, M.; Li, W. Experimental study on the thermal management performance of immersion cooling for 18650 lithium-ion battery module. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 192, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bai, M.; Zhou, Z.; Lv, J.; Hu, C.; Gao, L.; Peng, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, Y. Experimental study of liquid immersion cooling for different cylindrical lithium-ion batteries under rapid charging conditions. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 37, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D. A novel immersion cooling strategy for improving the thermal performance of lithium-ion battery packs. J. Energy Storage 2025, 141, 119121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Cifterler, N.; Amjady, N.; Date, A.; Kemper, H.; Khayyam, H. Enhancing energy and thermal efficiency of single-phase liquid immersion cooling systems for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2025, 131, 117365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, D.; Yuan, D.; Chang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, S. Effect of immersion cooling design optimization on thermal management for lithium battery module. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 272, 126401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Yuen, A.C.Y.; Wu, Y.; Fei, B.; Wang, J. Investigation on electro-thermal characteristics and heat transfer of immersion cooling for lithium-ion battery module at high-ambient temperature. J. Power Sources 2025, 645, 237238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J. Multi-objective optimization of parallel flow immersion cooling battery thermal management system with flow guide plates based on artificial neural network. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 274, 126833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, M.; Karamangil, M.I. Artificial neural networks-based multi-objective optimization of immersion cooling battery thermal management system using Hammersley sampling method. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 64, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, K.S.; Han, J.; Hwang, S.; Lee, M. Artificial Neural Network Modeling to Predict Thermal and Electrical Performances of Batteries with Direct Oil Cooling. Batteries 2023, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, M.; Tekin, M.; Karamangil, M.I. Artificial neural network predictions for temperature: Utilizing numerical analysis in immersion cooling systems using mineral oil and an engineered fluid for 32700 LiFePO4. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 211, 109742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh Patil, M.; Seo, J.; Lee, M. A novel dielectric fluid immersion cooling technology for Li-ion battery thermal management. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 229, 113715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Sarkar, J.; Mondal, S.S. Analysis of ternary hybrid nanofluid in microchannel-cooled cylindrical Li-ion battery pack using multi-scale multi-domain framework. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambros Telli, G.; Gungor, S.; Lorente, S. Counterflow canopy-to-canopy and U-turn liquid cooling solutions for battery modules in stationary Battery Energy Storage Systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 238, 121997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, L.; Bai, M.; Gao, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Song, Y. Experimental studies of liquid immersion cooling for 18650 lithium-ion battery under different discharging conditions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Peng, R.; Ping, P.; Du, J.; Chen, G.; Wen, J. A novel battery thermal management system coupling with PCM and optimized controllable liquid cooling for different ambient temperatures. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 204, 112280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Garud, K.S.; Hwang, S.; Lee, M. Experimental Study on Dielectric Fluid Immersion Cooling for Thermal Management of Lithium-Ion Battery. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambunathan, K.; Lai, E.; Moss, M.; Button, B. A review of heat transfer data for single circular jet impingement. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 1992, 13, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Shao, W. An optimization method for uniform flow distribution in the manifold of server cabinet. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Garud, K.S.; Kang, E.; Lee, M. Numerical Study on Heat Transfer Characteristics of Dielectric Fluid Immersion Cooling with Fin Structures for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Symmetry 2022, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Garud, K.S.; Park, S.C.; Lee, M. Heat Transfer Characteristics of an Electric Motor with Oil-Dripping Cooling under Overload Conditions. Symmetry 2024, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, M.; Ko, B. Numerical Analysis on Cooling Performances for Connectors Using Immersion Cooling in Ultra-Fast Chargers for Electric Vehicles. Symmetry 2025, 17, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Battery | ||

| Type | 21,700 | - |

| Nominal capacity | 4.80 | Ah |

| Nominal voltage | 3.64 | V |

| Maximum charge voltage | 4.20 | V |

| Discharge cut-off voltage | 2.50 | V |

| Diameter | 0.2 | mm |

| Height | 0.15 | mm |

| Weight | 1.5 | g |

| Battery module | ||

| Number of cells/module | 576 | - |

| Nominal battery module voltage | 87.36 | V |

| Maximum battery module voltage | 100.80 | V |

| Nominal battery module capacity | 10.06 | kWh |

| Maximum battery module capacity | 11.61 | kWh |

| Coefficient | Value | Coefficient | Value |

| a0 | 4.171265 | b0 | 19.69492 |

| a1 | −1.373891 | b1 | −41.07015 |

| a2 | 4.679367 | b2 | 275.0927 |

| a3 | −17.74574 | b3 | −674.2017 |

| a4 | 26.87833 | b4 | 703.2603 |

| a5 | −14.05492 | b5 | −259.2665 |

| C1 | 0 | C2 | 0 |

| Properties | Aluminum | Battery | Pitherm 150B | Plastic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) | 2702 | 2739.62 | 785.99 | 1070 |

| Specific heat (J/kg·K) | 903 | 1605 | 2188.3 | 1200 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) | 237 | 0.87 | 0.1363 | 0.17 |

| Dynamic viscosity (kg/m·s) | – | – | 0.0012 | – |

| Parameter | Range | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Hole size (A) | 8.66, 13.86, 17.32 | mm |

| Hole spacing (ΔH) | 6.0, 10.0, 14.0 | mm |

| Coolant mass flow rate (Vin) | 0.0131, 0.0262, 0.0393 | kg/s |

| Case | A (mm) | ΔH (mm) | Vin (kg/s) | Tmax (°C) | ΔTmax (°C) | ΔP (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.66 | 6.0 | 0.0131 | 45.25 | 20.25 | 15.77 |

| 2 | 8.66 | 6.0 | 0.0262 | 38.75 | 13.75 | 43.52 |

| 3 | 8.66 | 6.0 | 0.0393 | 36.15 | 11.15 | 83.78 |

| 4 | 8.66 | 10.0 | 0.0131 | 44.35 | 19.35 | 15.68 |

| 5 | 8.66 | 10.0 | 0.0262 | 38.25 | 13.25 | 43.44 |

| 6 | 8.66 | 10.0 | 0.0393 | 36.15 | 11.15 | 83.72 |

| 7 | 8.66 | 14.0 | 0.0131 | 43.45 | 18.45 | 15.59 |

| 8 | 8.66 | 14.0 | 0.0262 | 38.65 | 13.65 | 43.34 |

| 9 | 8.66 | 14.0 | 0.0393 | 35.85 | 10.85 | 83.36 |

| 10 | 13.86 | 6.0 | 0.0131 | 44.55 | 19.55 | 14.01 |

| 11 | 13.86 | 6.0 | 0.0262 | 38.15 | 13.15 | 37.41 |

| 12 | 13.86 | 6.0 | 0.0393 | 36.75 | 11.75 | 70.97 |

| 13 | 13.86 | 10.0 | 0.0131 | 44.35 | 19.35 | 14.02 |

| 14 | 13.86 | 10.0 | 0.0262 | 38.65 | 13.65 | 37.48 |

| 15 | 13.86 | 10.0 | 0.0393 | 36.25 | 11.25 | 70.85 |

| 16 | 13.86 | 14.0 | 0.0131 | 45.65 | 20.65 | 14.03 |

| 17 | 13.86 | 14.0 | 0.0262 | 38.75 | 13.75 | 37.44 |

| 18 | 13.86 | 14.0 | 0.0393 | 36.05 | 11.05 | 70.89 |

| 19 | 17.32 | 6.0 | 0.0131 | 43.85 | 18.85 | 13.73 |

| 20 | 17.32 | 6.0 | 0.0262 | 38.35 | 13.35 | 36.77 |

| 21 | 17.32 | 6.0 | 0.0393 | 36.15 | 11.15 | 69.55 |

| 22 | 17.32 | 10.0 | 0.0131 | 44.25 | 19.25 | 15.65 |

| 23 | 17.32 | 10.0 | 0.0262 | 38.95 | 13.95 | 43.40 |

| 24 | 17.32 | 10.0 | 0.0393 | 36.05 | 11.05 | 83.40 |

| 25 | 17.32 | 14.0 | 0.0131 | 43.45 | 18.45 | 13.73 |

| 26 | 17.32 | 14.0 | 0.0262 | 38.25 | 13.25 | 36.72 |

| 27 | 17.32 | 14.0 | 0.0393 | 35.75 | 10.75 | 69.12 |

| Design Type | A (mm) | ΔH (mm) | Vin (kg/s) | Tmax (°C) | ΔTmax (°C) | ΔP (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best cooling | 17.01 | 13.70 | 0.03844 | 35.85 | 10.85 | 67.52 |

| Best uniformity | 17.01 | 13.70 | 0.03844 | 35.85 | 10.85 | 67.52 |

| Lowest-pressure drop | 13.95 | 11.55 | 0.01317 | 44.32 | 19.32 | 13.24 |

| Balanced Solution (Optimized design) | 16.56 | 13.80 | 0.02723 | 37.97 | 12.97 | 38.00 |

| Performance Metrics | Prediction Value | Calculation Value | Relative Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax (°C) | 37.97 | 38.55 | 1.52 |

| ΔTmax (°C) | 12.97 | 13.55 | 4.47 |

| ΔP (Pa) | 38.00 | 38.97 | 2.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Le, T.D.; Bang, Y.-M.; Nguyen, N.-H.; Lee, M.-Y. Artificial Neural Network-Based Optimization of an Inlet Perforated Distributor Plate for Uniform Coolant Entry in 10 kWh 24S24P Cylindrical Battery Module. Symmetry 2026, 18, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010014

Le TD, Bang Y-M, Nguyen N-H, Lee M-Y. Artificial Neural Network-Based Optimization of an Inlet Perforated Distributor Plate for Uniform Coolant Entry in 10 kWh 24S24P Cylindrical Battery Module. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Tai Duc, You-Ma Bang, Nghia-Huu Nguyen, and Moo-Yeon Lee. 2026. "Artificial Neural Network-Based Optimization of an Inlet Perforated Distributor Plate for Uniform Coolant Entry in 10 kWh 24S24P Cylindrical Battery Module" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010014

APA StyleLe, T. D., Bang, Y.-M., Nguyen, N.-H., & Lee, M.-Y. (2026). Artificial Neural Network-Based Optimization of an Inlet Perforated Distributor Plate for Uniform Coolant Entry in 10 kWh 24S24P Cylindrical Battery Module. Symmetry, 18(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010014